Difference between revisions of "Timeline of nuclear waste management"

(Tags: Mobile edit, Mobile web edit) |

|||

| (53 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This is a '''timeline of nuclear waste management'''. | + | This is a '''timeline of nuclear waste management''', describing historic events and important treaties and policies that shaped the evolution of management of nuclear waste. |

==Big picture== | ==Big picture== | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| − | ! Time period !! Development summary | + | ! Time period !! Development summary !! More details |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | Late 19th century < || Early years || Health and safety concerns would be associated with radioactive materials throughout the twentieth century. However, the radioactive waste "problem" is early recognized at around the time of the discovery of {{w|radioactivity}} in 1895. {{w|Radium}}, like {{w|x-ray}}s, is soon adopted for several industrial uses; for example, workers in the 1910s and 1920s paint watch dials with radium so that they would glow in the dark. Observers would soon note that these radioactive materials are associated with harmful side effects. Efforts in response to the recognition of the health effects of radioactive materials result in the formation of the [[w:International Commission on Radiological Protection|International Committee on Radiation Protection]] in 1928.<ref name='A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue'>{{cite web |title=A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue |url=http://nucleargreen.blogspot.com/2008/03/history-of-nuclear-waste-issue.html?m=1 |website=nucleargreen.blogspot.com |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1930s–1940s || Primary focus on nuclear weapons || Industrial work with radioactive materials is relatively small in scale through the 1930s, but events during and after {{w|World War II}} would change matters dramatically. The work done to construct atomic weapons begins, and still today it continues to have profound environmental and political effects in the contemporary world. Waste management is not a high priority during WWII, and not much thought is given to the development of a long-term waste disposal plan.<ref name='A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue'/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1950s < || Civilian nuclear waste era || The use of {{w|nuclear reactor}}s for commercial power generation begins in the mid-1950s. By the late 1950s, experts involved with the commercial waste problem recommend a strategy of geologic storage of high-level radioactive waste from commercial nuclear power plants as the preferred long-term disposal option. By isolating wastes deep in underground caverns, these materials could be safely removed from contact with the biosphere. By the early 1960s, geologic storage becomes the accepted waste management strategy within the AEC. Electric utilities begin to invest in nuclear plants in the in mid-1960s, and the industry booms as the cost of {{w|fossil fuel}}s skyrocket in response to the {{w|Arab Oil Embargo}} of 1973.<ref name="Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges"/> As a result, the amount of nuclear waste produced increases exponentially. In the 1970s and 1980s, nuclear agencies in France and around the world propose the idea of firing the waste into space in a rocket or putting it deep in the ocean. Both would be eventually rejected as too dangerous, with fears that a rocket could explode in the atmosphere and the {{w|radiation}} could leak into the ocean. In the 1990s, governments and scientists seem to have converged on the idea of burying the radioactive waste in storage facilities designed to last for ever.<ref name="Nuclear waste: keep out for 100,000 years">{{cite web |title=Nuclear waste: keep out for 100,000 years |url=https://www.ft.com/content/db87c16c-4947-11e6-b387-64ab0a67014c |website=ft.com |accessdate=30 June 2018}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

==Full timeline== | ==Full timeline== | ||

| Line 15: | Line 20: | ||

! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Geographical location | ! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Geographical location | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1895 || || German physicist {{w|Wilhelm Röntgen}} discovers {{w|X ray}}s.<ref name="Clarke"/> || | + | | 1895 || Scientific development || German physicist {{w|Wilhelm Röntgen}} discovers {{w|X ray}}s.<ref name="Clarke"/> || {{w|Germany}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1896 || Scientific development || French physicist {{w|Henry Becquerel}} identifies radioactivity.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jayawardhana |first1=Ray |title=The Neutrino Hunters |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=bLxpAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT28&dq=%22in+1896%22+French+physicist+Henri+Becquerel+identifies+radioactivity.&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwirneCf-vvbAhWDE5AKHd-MAP8Q6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22in%201896%22%20French%20physicist%20Henri%20Becquerel%20identifies%20radioactivity.&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Francis |first1=Charles |title=Light after Dark II: The Large and the Small |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=UFAYDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA178&dq=%22in+1896%22+French+physicist+Henri+Becquerel+identifies+radioactivity.&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwirneCf-vvbAhWDE5AKHd-MAP8Q6AEILjAB#v=onepage&q=%22in%201896%22%20French%20physicist%20Henri%20Becquerel%20identifies%20radioactivity.&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Russell |first1=Peter J. |title=Biology: The Dynamic Science, Volume 1 w/ PAC |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=VYMFAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA26&dq=%22in+1896%22+French+physicist+Henri+Becquerel+identifies+radioactivity.&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwirneCf-vvbAhWDE5AKHd-MAP8Q6AEINDAC#v=onepage&q=%22in%201896%22%20French%20physicist%20Henri%20Becquerel%20identifies%20radioactivity.&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|France}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1898 || Scientific development || French scientists [[w:Pierre Curie|Pierre]] and {{w|Marie Curie}} announce that they have identified a new element, {{w|radium}}, that has radioactive properties.<ref name='A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue'/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1928 || Organization || The [[w:International Commission on Radiological Protection|International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC)]] is founded at the second International Congress of Radiology in {{w|Stockholm}}.<ref name="Clarke">{{cite journal|last=Clarke|first=R.H.|author2=J. Valentin|title=The History of ICRP and the Evolution of its Policies|journal=Annals of the ICRP|year=2009|volume=39|series=ICRP Publication 109|issue=1|pages=75–110|doi=10.1016/j.icrp.2009.07.009|url=http://www.icrp.org/docs/The%20History%20of%20ICRP%20and%20the%20Evolution%20of%20its%20Policies.pdf|accessdate=12 May 2012}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | | 1928 || Organization || The [[w:International Commission on Radiological Protection|International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC)]] is founded at the second International Congress of Radiology in {{w|Stockholm}}.<ref name="Clarke">{{cite journal|last=Clarke|first=R.H.|author2=J. Valentin|title=The History of ICRP and the Evolution of its Policies|journal=Annals of the ICRP|year=2009|volume=39|series=ICRP Publication 109|issue=1|pages=75–110|doi=10.1016/j.icrp.2009.07.009|url=http://www.icrp.org/docs/The%20History%20of%20ICRP%20and%20the%20Evolution%20of%20its%20Policies.pdf|accessdate=12 May 2012}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1942 || Scientific development || The first self-sustaining nuclear reaction is created in a scientific facility at the {{w|University of Chicago}}.<ref name="The International Atomic Energy Agency"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1945 || Background || The first successful test of atomic bomb takes place in {{w|Alamogordo}}, {{w|New Mexico}}. In the same year, the {{w|United States}} drops atomic bombs on {{w|Hiroshima}} and {{w|Nagasaki}}.<ref name="The International Atomic Energy Agency"/> || {{w|United States}}, {{w|Japan}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1946 || Organization || The {{w|United States Atomic Energy Commission}} is founded.<ref>{{cite web |title=Atomic Energy Commission - 25 Year Anniversary (1971) |url=https://www.orau.org/ptp/collection/medalsmementoes/AEC25years.htm |website=orau.org |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Cleveland |first1=Cutler J. |title=Concise Encyclopedia of the History of Energy |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=JPjqRIIWHcoC&pg=PA175&dq=United+States+Atomic+Energy+Commission+%22in+1946%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi52vyc4PnbAhXClJAKHRaKC4AQ6AEIOTAD#v=onepage&q=United%20States%20Atomic%20Energy%20Commission%20%22in%201946%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Doyle |first1=James |title=Nuclear Safeguards, Security and Nonproliferation: Achieving Security with Technology and Policy |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=8WOza_y3IkQC&pg=PA19&dq=United+States+Atomic+Energy+Commission+%22in+1946%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi52vyc4PnbAhXClJAKHRaKC4AQ6AEIPjAE#v=onepage&q=United%20States%20Atomic%20Energy%20Commission%20%22in%201946%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1946 || Policy || A trefoil — three black blades on a yellow background — is created as the international warning symbol for radiation.<ref name="Nuclear waste: keep out for 100,000 years"/> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1950 || Organization || The [[w:International Commission on Radiological Protection|International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC)]] is restructured to take account of new uses of radiation outside the medical area, and is renamed International Commission on Radiological Protection.<ref name="Clarke"/> || | | 1950 || Organization || The [[w:International Commission on Radiological Protection|International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC)]] is restructured to take account of new uses of radiation outside the medical area, and is renamed International Commission on Radiological Protection.<ref name="Clarke"/> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1957 (July 29) || Organization || The {{w|International Atomic Energy Agency}} is established. || | + | | 1955 – 1957 || Policy || The {{w|United States Atomic Energy Commission}} requests that the National Academy of Sciences consider the possibilities of disposing of high-level radioactive waste in quantity within the continental limits of the country. This request would lead to a conference at {{w|Princeton}} in 1955 and the subsequent 1957 report ''The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land''. The problem posed to the National Academy of Sciences at that time is primarily the disposal of fission products from the reactors used in weapons manufacture.<ref name="Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges"/> || {{w|United States}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1956 || Power plant || {{w|Calder Hall}}, the first commercial nuclear power station for civil use, opens in {{w|Sellafield}}, {{w|England}}.<ref name="History of nuclear power corporate.vattenfall.com">{{cite web|title=History of nuclear power|url=https://corporate.vattenfall.com/about-energy/non-renewable-energy-sources/nuclear-power/history/|website=corporate.vattenfall.com|accessdate=30 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1957 (July 29) || Organization || The {{w|International Atomic Energy Agency}} is established. It is an autonomous intergovernmental organization dedicated to increasing the contribution of atomic energy to the world’s peace and well-being and ensuring that agency assistance is not used for military purposes.<ref>{{cite web |title=International Atomic Energy Agency |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/International-Atomic-Energy-Agency |website=britannica.com |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref><ref name="The International Atomic Energy Agency">{{cite book |last1=Olwell |first1=Russell B. |title=The International Atomic Energy Agency |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=vIreZXpGPjkC&pg=PA104&dq=%221957%22+%22International+Atomic+Energy+Agency%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjlmp-m7fnbAhVQPJAKHSZoAnEQ6AEISzAJ#v=onepage&q=%221957%22%20%22International%20Atomic%20Energy%20Agency%22&f=false}}</ref><ref name="IAEA">{{cite web |title=IAEA |url=https://www.iaea.org/about/overview/history |website=iaea.org |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref> The IAEA is headquartered in {{w|Vienna}}. || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1957 || Publication || The United States [[w:National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine|National Research Council]] publishes the report ''The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land'', one of the first technical analyses of the geological disposal option. The publication marks the beginning of a four-decade effort by the national government to identify a disposal site for commercial spent fuel and defense waste ({{w|high-level waste}}).<ref name="Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges">{{cite web |title=Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges |url=https://www.nap.edu/read/9674/chapter/2 |website=nap.edu |accessdate=11 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | | 1957 || Publication || The United States [[w:National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine|National Research Council]] publishes the report ''The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land'', one of the first technical analyses of the geological disposal option. The publication marks the beginning of a four-decade effort by the national government to identify a disposal site for commercial spent fuel and defense waste ({{w|high-level waste}}).<ref name="Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges">{{cite web |title=Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges |url=https://www.nap.edu/read/9674/chapter/2 |website=nap.edu |accessdate=11 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1957 || Storage || Extensive geological investigations start in Russia for suitable injection layers for radioactive waste, an approach that involves the injection of liquid radioactive waste directly into a layer of rock deep underground. Three sites are found, all in sedimentary rocks, at {{w|Krasnoyarsk}}, {{w|Tomsk}}, and {{w|Dimitrovgrad}}. In total, some tens of millions of cubic metres of {{w|low-level waste}}, {{w|intermediate-level waste}} and {{w|high-level waste}} would be injected in Russia.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Russia}} | | 1957 || Storage || Extensive geological investigations start in Russia for suitable injection layers for radioactive waste, an approach that involves the injection of liquid radioactive waste directly into a layer of rock deep underground. Three sites are found, all in sedimentary rocks, at {{w|Krasnoyarsk}}, {{w|Tomsk}}, and {{w|Dimitrovgrad}}. In total, some tens of millions of cubic metres of {{w|low-level waste}}, {{w|intermediate-level waste}} and {{w|high-level waste}} would be injected in Russia.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Russia}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1959 || || The {{w|United States Atomic Energy Commission}} licenses commercial boats to haul 55-gallon drums filled with radioactive wastes out to sea, to be dumped overboard into deep water. Managers reason that the barrels would sink deeply enough that, even if they corroded or ruptured, the wastes would be sufficiently diluted in the ocean to pose no danger.<ref name='A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue'/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1961 || Facility || An {{w|International Atomic Energy Agency}} lab opens in {{w|Austria}}, creating a channel for cooperative global nuclear research.<ref name="The International Atomic Energy Agency"/> || {{w|Austria}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1968 – 2002 || || Approximately 47,000 tonnes of nuclear waste are produced in the period by commercial reactors in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Herbst |first1=Alan M. |last2=Hopley |first2=George W. |title=Nuclear Energy Now: Why the Time Has Come for the World's Most Misunderstood Energy Source |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=HcvF9JmaNgUC&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=47,000+tonnes+of+high-level+nuclear+waste+stored+in+the+USA+in+2002&source=bl&ots=GHmqeyTLs1&sig=SBk4PpD1QER2SwXmuIyUUXTBpBE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiM4IiakcjbAhWCIZAKHdEMDHQQ6AEIXzAF#v=onepage&q=47%2C000%20tonnes%20of%20high-level%20nuclear%20waste%20stored%20in%20the%20USA%20in%202002&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | | 1968 – 2002 || || Approximately 47,000 tonnes of nuclear waste are produced in the period by commercial reactors in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Herbst |first1=Alan M. |last2=Hopley |first2=George W. |title=Nuclear Energy Now: Why the Time Has Come for the World's Most Misunderstood Energy Source |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=HcvF9JmaNgUC&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=47,000+tonnes+of+high-level+nuclear+waste+stored+in+the+USA+in+2002&source=bl&ots=GHmqeyTLs1&sig=SBk4PpD1QER2SwXmuIyUUXTBpBE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiM4IiakcjbAhWCIZAKHdEMDHQQ6AEIXzAF#v=onepage&q=47%2C000%20tonnes%20of%20high-level%20nuclear%20waste%20stored%20in%20the%20USA%20in%202002&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || Study || A study by the United States {{w|National Academy of Science}}, determines that the federal government should build a permanent geologic repository for high-level nuclear waste.<ref name="History of Nuclear Waste Policy">{{cite web |title=History of Nuclear Waste Policy |url=http://berniesteam.com/industry-services/bt-dry-cask-storage-services/history-of-nuclear-waste-policy/ |website=berniesteam.com |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1970s || Storage || In the United States, direct injection of about 7500 cubic metres of {{w|low-level waste}} as cement slurries is undertaken during the decade, at a depth of about 300 meters over a period of 10 years at the {{w|Oak Ridge National Laboratory}}, {{w|Tennessee}}. It would later be abandoned because of uncertainties over the migration of the grout in the surrounding fractured rocks (shales).<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|United States}} | | 1970s || Storage || In the United States, direct injection of about 7500 cubic metres of {{w|low-level waste}} as cement slurries is undertaken during the decade, at a depth of about 300 meters over a period of 10 years at the {{w|Oak Ridge National Laboratory}}, {{w|Tennessee}}. It would later be abandoned because of uncertainties over the migration of the grout in the surrounding fractured rocks (shales).<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| Line 39: | Line 64: | ||

| 1977 || Organization || Germany’s Gesellschaft für Nuklear-Service mbH (GNS) is set up. Owned by the country's four nuclear utilities, is both an operator of waste storage and supplier of storage casks.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Germany}} | | 1977 || Organization || Germany’s Gesellschaft für Nuklear-Service mbH (GNS) is set up. Owned by the country's four nuclear utilities, is both an operator of waste storage and supplier of storage casks.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Germany}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1978 || Facility || After five years of pilot plant operation, France's large AVM (Atelier de Vitrification Marcoule) plant starts up, turning cubic feet of concentrated high-level nuclear wastes into solid glass.<ref name="NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL: BOLD INNOVATIONS ABROAD INSTRUCTIVE FOR U.S."/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Toumanov |first1=I. N. |title=Plasma and High Frequency Processes for Obtaining and Processing Materials in the Nuclear Fuel Cycle |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=eSAkBkAZ-J4C&pg=PA574&lpg=PA574&dq=Atelier+de+Vitrification+Marcoule&source=bl&ots=BaX55EoWBu&sig=HGaePOzwPvoazaDyiBvNJ83o70I&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwis6ujsx_zbAhXMhpAKHeXbBCMQ6AEIVjAH#v=onepage&q=Atelier%20de%20Vitrification%20Marcoule&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ojovan |first1=Michael I |title=Handbook of Advanced Radioactive Waste Conditioning Technologies |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=qoxwAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA163&dq=Atelier+de+Vitrification+Marcoule+%221978%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwik87aAyPzbAhXBlJAKHTB6BlYQ6AEINjAC#v=onepage&q=Atelier%20de%20Vitrification%20Marcoule%20%221978%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1979 || Organization || The {{w|Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Bau und Betrieb von Endlagern für Abfallstoffe mbH}} (DBE) (The [[w:Germany|German]] Society for the construction and operation of waste repositories) is founded and based in {{w|Peine}}. The company employs approximately 570 employees and is for 75% owned by the {{w|Gesellschaft für Nuklear-Service}} (GNS).<ref>{{cite web |title=Änderung des Atomgesetzes wegen Asse |url=http://www.udo-leuschner.de/energie-chronik/081112.htm |website=udo-leuschner.de |accessdate=11 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Germany}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1979 || | + | | 1979 || Crisis || The {{w|Three mile island accident}} is the worst accident in United States commercial reactor history. The accident is caused by a loss of coolant from the reactor core due to a combination of mechanical malfunction and human error. However, no one is injured, and no overexposure to radiation results from the accident.<ref name="History of nuclear power corporate.vattenfall.com"/><ref name="The History Of Nuclear Energy">{{cite web|title=The History Of Nuclear Energy|url=https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/The%20History%20of%20Nuclear%20Energy_0.pdf|website=energy.gov|accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref><ref name="The International Atomic Energy Agency"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1980 || Organization || The Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, known as SKB) is created. It is responsible for final disposal of nuclear waste in the country. || {{w|Sweden}} | | 1980 || Organization || The Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, known as SKB) is created. It is responsible for final disposal of nuclear waste in the country. || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

| Line 54: | Line 79: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1982 || Storage facility || The {{w|Lanyu storage site}}, a nuclear waste storage facility, is built at the Southern tip of {{w|Orchid Island}} in {{w|Taitung County}}, offshore of Taiwan Island. It is owned and operated by {{w|Taipower Company}}. The facility receives nuclear waste from Taipower's current three nuclear power plants. However, due to the strong resistance from local community in the island, the nuclear waste has to be stored at the power plant facilities themselves.<ref>{{cite web |title=Premier reiterates promise of end to Lanyu nuclear waste storage |url=http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201304030025.aspx |website=focustaiwan.tw |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Tao protest against nuclear facility |url=http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2012/02/21/2003525985 |website=taipeitimes.com |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Taiwan}} | | 1982 || Storage facility || The {{w|Lanyu storage site}}, a nuclear waste storage facility, is built at the Southern tip of {{w|Orchid Island}} in {{w|Taitung County}}, offshore of Taiwan Island. It is owned and operated by {{w|Taipower Company}}. The facility receives nuclear waste from Taipower's current three nuclear power plants. However, due to the strong resistance from local community in the island, the nuclear waste has to be stored at the power plant facilities themselves.<ref>{{cite web |title=Premier reiterates promise of end to Lanyu nuclear waste storage |url=http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201304030025.aspx |website=focustaiwan.tw |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Tao protest against nuclear facility |url=http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2012/02/21/2003525985 |website=taipeitimes.com |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Taiwan}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1982 || Policy || United States President {{w|Jimmy Carter}}, concerned about the possibility of nuclear proliferation, bans commercial reprocessing of spent fuel for private companies, leaving no long-term option for spent fuel storage and reprocessing available to utilities.<ref name="History of Nuclear Waste Policy"/><ref name="Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing: U.S. Policy Development">{{cite web |title=Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing: U.S. Policy Development |url=https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RS22542.html |website=everycrsreport.com |accessdate=30 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1983 || Policy || A {{w|Nuclear Waste Policy Act}} requires the {{w|United States Department of Energy}} to start taking utilities’ spent fuel by Jan. 31, 1998. It directs [[w:United States Department of Energy|DOE]] to begin studying sites for permanent repositories and establishes a schedule for that process.<ref name="History of Nuclear Waste Policy"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1985 || || Sweden starts operating a radioactive waste sea transport system. A specially built ship, the M/S Sigyn, carries all radioactive waste between nuclear facilities and the national Central Interim Storage Facility for Spent Nuclear Fuel, located in {{w|Oskarshamn}} in southern Sweden.<ref name="doe2001"/> || {{w|Sweden}} | | 1985 || || Sweden starts operating a radioactive waste sea transport system. A specially built ship, the M/S Sigyn, carries all radioactive waste between nuclear facilities and the national Central Interim Storage Facility for Spent Nuclear Fuel, located in {{w|Oskarshamn}} in southern Sweden.<ref name="doe2001"/> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1987 || || The United States Nuclear Waste Policy Act is amended to designate Yucca Mountain, located in the remote Nevada desert, as the sole national repository for spent fuel and {{w|high-level waste}} from nuclear power and military defence programs.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste">{{cite web |title=Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste |url=http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-waste/storage-and-disposal-of-radioactive-waste.aspx |website=world-nuclear.org |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | + | | 1986 || Crisis || The {{w|Chernobyl disaster}} occurs after a safety test deliberately turns off [[w:Control rod|safety systems]]. A large amount of radiation occurs, over fifty firefighter die, and up to 4,000 civilians are estimated to die of early cancer.<ref name="History of Nuclear Energy whatisnuclear.com">{{cite web|title=History of Nuclear Energy|url=https://whatisnuclear.com/articles/nuclear_history.html|website=whatisnuclear.com|accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Ukraine}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1987 || Policy || The United States Nuclear Waste Policy Act is amended to designate Yucca Mountain, located in the remote Nevada desert, as the sole national repository for spent fuel and {{w|high-level waste}} from nuclear power and military defence programs.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste">{{cite web |title=Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste |url=http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-waste/storage-and-disposal-of-radioactive-waste.aspx |website=world-nuclear.org |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1988 || Facility || The Swedish Final Repository for Radioactive Operational Waste (SFR) starts operations for disposal of low-level short-lived radioactive waste. The first of its kind in the world, in granite rock 50 meters (164 feet) below the {{w|Baltic Sea}}, the SFR is 60 meters offshore, connected by a tunnel to the site of the {{w|Forsmark nuclear power plant}} in central Sweden.<ref name="doe2001">{{cite web |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy |date=June 2001 |title=Sweden’s radioactive waste management program |url=http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0416.shtml |accessdate=2008-12-24 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090118220403/http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/factsheets/doeymp0416.shtml <!--Added by H3llBot--> |archivedate=2009-01-18}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1988 || || | + | | 1988 – 1990 || Study || In 1988, the United States [[w:Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board|Board on Radioactive Waste Management]] convenes a study session with experts from the United States and abroad to discuss U.S. policies and programs for managing the nation's spent fuel and high-level waste. In 1990, the board would publish report ''Rethinking High-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal'', which provides a broad assessment of the technical and policy challenges for developing a repository for the disposition of high-level waste. The report notes that: “There is a strong worldwide consensus that the best, safest long-term option for dealing with HLW is geological isolation…. Although the scientific community has high confidence that the general strategy of geological isolation is the best one to pursue, the challenges are formidable.”<ref name="Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1989 (March 22) || || The {{w|Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal}} is signed. The agreement provides the general framework for the minimization of international movement and the environmentally safe management of hazardous wastes.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Coles |first1=Richard |last2=Lorenzon |first2=Filippo |title=Law of Yachts & Yachting |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=NZk3AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA309&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEITTAG#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Wolfrum |first1=Rüdiger |last2=WOLFRUM |first2=R. |last3=Matz |first3=Nele |title=Conflicts in International Environmental Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=br0SGSdkCv4C&pg=PA100&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEIVzAI#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sands |first1=Philippe |last2=Peel |first2=Jacqueline |last3=MacKenzie |first3=Ruth |title=Principles of International Environmental Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=uHzFRub4KrAC&pg=PA572&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEIRTAF#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|Switzerland}} | + | | 1989 (March 22) || Treaty || The {{w|Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal}} is signed. The agreement provides the general framework for the minimization of international movement and the environmentally safe management of hazardous wastes.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Coles |first1=Richard |last2=Lorenzon |first2=Filippo |title=Law of Yachts & Yachting |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=NZk3AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA309&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEITTAG#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Wolfrum |first1=Rüdiger |last2=WOLFRUM |first2=R. |last3=Matz |first3=Nele |title=Conflicts in International Environmental Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=br0SGSdkCv4C&pg=PA100&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEIVzAI#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sands |first1=Philippe |last2=Peel |first2=Jacqueline |last3=MacKenzie |first3=Ruth |title=Principles of International Environmental Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=uHzFRub4KrAC&pg=PA572&dq=%221989%22+%22Basel+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij_9HHjcXbAhXJS5AKHZRVBSwQ6AEIRTAF#v=onepage&q=%221989%22%20%22Basel%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|Switzerland}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1991 (January 30) || Treaty || The Convention on the Ban of Imports into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa ({{w|Bamako Convention}}) is adopted by African governments in {{w|Bamako}}, {{w|Mali}}.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sands |first1=Philippe |title=Principles of International Environmental Law I: Frameworks, Standards, and Implementation |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=xd9RAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA507&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEILDAB#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kummer |first1=Katharina |title=International Management of Hazardous Wastes: The Basel Convention and Related Legal Rules |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=43LZ0smxC5AC&pg=PA99&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEIMjAC#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Marr |first1=Simon |title=The Precautionary Principle in the Law of the Sea: Modern Decision Making in International Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ynGLz1FqgvYC&pg=PA191&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEIODAD#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|Mali}} | | 1991 (January 30) || Treaty || The Convention on the Ban of Imports into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa ({{w|Bamako Convention}}) is adopted by African governments in {{w|Bamako}}, {{w|Mali}}.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sands |first1=Philippe |title=Principles of International Environmental Law I: Frameworks, Standards, and Implementation |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=xd9RAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA507&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEILDAB#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kummer |first1=Katharina |title=International Management of Hazardous Wastes: The Basel Convention and Related Legal Rules |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=43LZ0smxC5AC&pg=PA99&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEIMjAC#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Marr |first1=Simon |title=The Precautionary Principle in the Law of the Sea: Modern Decision Making in International Law |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ynGLz1FqgvYC&pg=PA191&dq=%221991%22+%22Bamako+Convention%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPwaTyisXbAhUDHZAKHRK5AEEQ6AEIODAD#v=onepage&q=%221991%22%20%22Bamako%20Convention%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|Mali}} | ||

| Line 71: | Line 104: | ||

| 1996 || Legal || The 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (known as the London Protocol) enters into force. Rather than stating which materials may not be dumped into the sea, the convention prohibits all dumping, except for possibly acceptable wastes.<ref name="Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter">{{cite web |title=Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter |url=http://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/ListOfConventions/Pages/Convention-on-the-Prevention-of-Marine-Pollution-by-Dumping-of-Wastes-and-Other-Matter.aspx |website=imo.org |accessdate=10 June 2018}}</ref> || | | 1996 || Legal || The 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (known as the London Protocol) enters into force. Rather than stating which materials may not be dumped into the sea, the convention prohibits all dumping, except for possibly acceptable wastes.<ref name="Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter">{{cite web |title=Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter |url=http://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/ListOfConventions/Pages/Convention-on-the-Prevention-of-Marine-Pollution-by-Dumping-of-Wastes-and-Other-Matter.aspx |website=imo.org |accessdate=10 June 2018}}</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1997 || || {{w|Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management}}. || | + | | 1997 || Treaty || The {{w|Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management}} takes place in {{w|Vienna}} as an {{w|International Atomic Energy Agency}} (IAEA) treaty. It is the first treaty to address radioactive waste management on a global scale.<ref>{{cite web |title=Results of Review Meetings |url=http://www-ns.iaea.org/conventions/results-meetings.asp?s=6&l=40 |website=ns.iaea.org |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management |url=https://www.iaea.org/topics/nuclear-safety-conventions/joint-convention-safety-spent-fuel-management-and-safety-radioactive-waste |website=iaea.org |accessdate=29 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Austria}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1997 || Facility || A near-surface disposal facility in cavern below ground level opens in {{w|Loviisa}}, {{w|Finland}}. The depth of this is about 100 meters.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Finland}} | | 1997 || Facility || A near-surface disposal facility in cavern below ground level opens in {{w|Loviisa}}, {{w|Finland}}. The depth of this is about 100 meters.<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/> || {{w|Finland}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1998 (April 22) || || The {{w|Bamako Convention}} comes into force.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Bamako convention |url=https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/environmental-governance/what-we-do/strengthening-institutions/bamako-convention |website=unenvironment.org |accessdate=10 June 2018}}</ref> || | + | | 1998 (April 22) || Treaty || The {{w|Bamako Convention}} comes into force.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Bamako convention |url=https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/environmental-governance/what-we-do/strengthening-institutions/bamako-convention |website=unenvironment.org |accessdate=10 June 2018}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| 1999 || Facility || The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) becomes operational in {{w|New Mexico}} for defence transuranic wastes (long-lived [[w:radioactive waste|intermediate-level waste]]).<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/><ref>{{cite web |title=Waste Isolation Pilot Plant |url=https://www.energy.gov/em/waste-isolation-pilot-plant |website=energy.gov |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | | 1999 || Facility || The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) becomes operational in {{w|New Mexico}} for defence transuranic wastes (long-lived [[w:radioactive waste|intermediate-level waste]]).<ref name="Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste"/><ref>{{cite web |title=Waste Isolation Pilot Plant |url=https://www.energy.gov/em/waste-isolation-pilot-plant |website=energy.gov |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000s || Storage || {{w|Dry cask storage}} is used in the United States, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Japan, Armenia, Argentina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, South Korea, Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine and Lithuania.<ref name="Agency2007">{{cite book|author=OECD Nuclear Energy Agency|title=Management of recyclable fissile and fertile materials|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E1UuVHi7CDAC&pg=PA34|accessdate=9 June 2018|date=May 2007|publisher=OECD Publishing|isbn=978-92-64-03255-2|page=34}}</ref> || {{w|United States}}, {{w|Canada}}, {{w|Germany}}, {{w|Switzerland}}, {{w|Spain}}, {{w|Belgium}}, {{w|Sweden}}, the {{w|United Kingdom}}, {{w|Japan}}, {{w|Armenia}}, {{w|Argentina}}, {{w|Bulgaria}}, {{w|Czech Republic}}, {{w|Hungary}}, {{w|South Korea}}, {{w|Romania}}, {{w|Slovakia}}, {{w|Ukraine}}, {{w|Lithuania}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2002 || Storage || After over 30 years of scientific and technological studies, the United States President and [[w:United States Congress|Congress]] approve the {{w|Yucca Mountain}} site as suitable for a repository os nuclear waste.<ref name="NATIONAL NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL PROGRAM"/> || {{w|United States}} | | 2002 || Storage || After over 30 years of scientific and technological studies, the United States President and [[w:United States Congress|Congress]] approve the {{w|Yucca Mountain}} site as suitable for a repository os nuclear waste.<ref name="NATIONAL NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL PROGRAM"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| Line 87: | Line 122: | ||

| 2011 || Organization || {{w|Magnox Ltd}} is founded as a nuclear waste company. It is responsible for the decommissioning of ten {{w|Magnox}} {{w|nuclear power station}}s in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web |title=It's all boiled down to this... |url=https://magnoxsites.com/2014/11/its-all-boiled-down-to-this |website=magnoxsites.com |accessdate=11 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | | 2011 || Organization || {{w|Magnox Ltd}} is founded as a nuclear waste company. It is responsible for the decommissioning of ten {{w|Magnox}} {{w|nuclear power station}}s in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web |title=It's all boiled down to this... |url=https://magnoxsites.com/2014/11/its-all-boiled-down-to-this |website=magnoxsites.com |accessdate=11 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2013 || Publication || Documentary ''Journey to the Safest Place on Earth'' is released. It discusses the huge quantity of radioactive waste and spent fuel rods being stored at various locations on the planet. || | + | | 2013 || Publication || Documentary ''{{w|Journey to the Safest Place on Earth}}'' is released. It discusses the huge quantity of radioactive waste and spent fuel rods being stored at various locations on the planet. || |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017 || Storage || France's {{w|Areva}} launches the NUHOMS Matrix advanced used nuclear fuel storage overpack, a high-density system for storing multiple spent fuel rods in canisters.<ref name=wnn-20170929>{{cite news |url=http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/WR-Arevas-space-saving-solution-for-used-fuel-storage-2909175.html |title=Areva's space-saving solution for used fuel storage |publisher=World Nuclear News |date=29 September 2017 |accessdate=9 June 2018}}</ref> || {{w|France} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2024 || || Belgium builds a new type of nuclear reactor near Antwerp, powered by a particle accelerator, called Myrrha. This reactor is designed to produce 100 times less waste than traditional reactors and is seen as a potential tool in cancer treatment. It is expected to be safer, able to shut down in milliseconds, and will initially produce medical radioisotopes. The project, funded by the Belgian government and the EU, aims to be fully operational by 2036-2038. Myrrha could significantly reduce nuclear waste lifespan from 300,000 years to 300 years by transmuting waste, making it a pioneering effort in nuclear technology.<ref>{{cite web |title=Reactor nuclear subcrítico producirá en un segundo energía para todo un año |url=https://www.dw.com/es/reactor-nuclear-subcr%C3%ADtico-producir%C3%A1-en-un-segundo-energ%C3%ADa-para-todo-un-a%C3%B1o/a-69480786 |website=DW |date=25 June 2024 |access-date=26 June 2024}}</ref> || {{w|Belgium}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |} |

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

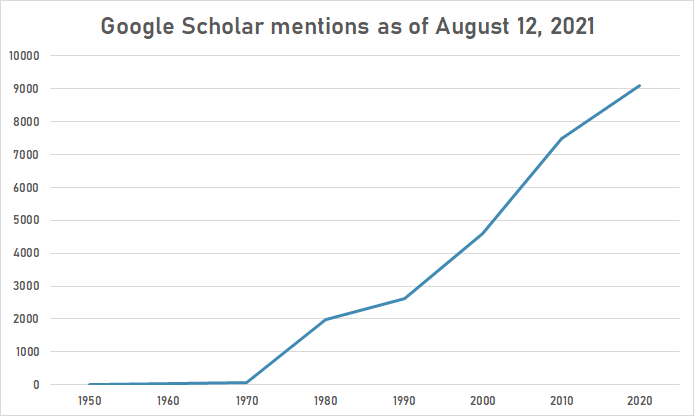

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of August 12, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! "nuclear waste" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1950 || 4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960 || 41 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || 62 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 1,990 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 2,620 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 4,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 7,480 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 9,080 | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nuclear waste google schoolar.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Trends === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The image below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Nuclear waste management (Search term), from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Nuclear waste management |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=Nuclear%20waste%20management |website=Google Trends |access-date=25 March 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nuclear waste management gt.png|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comparative chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for nuclear waste management and nuclear waste from 1950 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=nuclear waste management and nuclear waste |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=nuclear+waste+management%2C+nuclear+waste&year_start=1950&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cnuclear%20waste%20management%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cnuclear%20waste%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cnuclear%20waste%20management%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cnuclear%20waste%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=12 April 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nuclear waste management and nuclear waste ngram.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Nuclear waste management}}, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to February 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Nuclear waste management |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Nuclear+waste+management&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=25 March 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nuclear waste management wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

==Meta information on the timeline== | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

| Line 103: | Line 188: | ||

===What the timeline is still missing=== | ===What the timeline is still missing=== | ||

| − | [https:// | + | |

| + | * {{w|List of radioactive waste treatment technologies}} | ||

| + | * {{w|List of waste disposal incidents}} | ||

| + | * [https://bigthink.com/technology-innovation/laser-nuclear-waste?fbclid=IwAR1We3krCrOdsezUVE5RmaPNgk7xG8AGlZbgeO5aK1JugQ9yCcRYeF4jGVc] | ||

| + | * [https://bigthink.com/technology-innovation/laser-nuclear-waste?utm_medium=Social&facebook=1&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR0dl2KfT_v3PXMJQywZn-NqNrAME6fgm0t5badARSchasGMuatnEdAlkLE#Echobox=1608477916] | ||

===Timeline update strategy=== | ===Timeline update strategy=== | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Timeline of waste management]] | ||

| + | * [[Timeline of nuclear energy]] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Latest revision as of 09:52, 26 June 2024

This is a timeline of nuclear waste management, describing historic events and important treaties and policies that shaped the evolution of management of nuclear waste.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| Late 19th century < | Early years | Health and safety concerns would be associated with radioactive materials throughout the twentieth century. However, the radioactive waste "problem" is early recognized at around the time of the discovery of radioactivity in 1895. Radium, like x-rays, is soon adopted for several industrial uses; for example, workers in the 1910s and 1920s paint watch dials with radium so that they would glow in the dark. Observers would soon note that these radioactive materials are associated with harmful side effects. Efforts in response to the recognition of the health effects of radioactive materials result in the formation of the International Committee on Radiation Protection in 1928.[1] |

| 1930s–1940s | Primary focus on nuclear weapons | Industrial work with radioactive materials is relatively small in scale through the 1930s, but events during and after World War II would change matters dramatically. The work done to construct atomic weapons begins, and still today it continues to have profound environmental and political effects in the contemporary world. Waste management is not a high priority during WWII, and not much thought is given to the development of a long-term waste disposal plan.[1] |

| 1950s < | Civilian nuclear waste era | The use of nuclear reactors for commercial power generation begins in the mid-1950s. By the late 1950s, experts involved with the commercial waste problem recommend a strategy of geologic storage of high-level radioactive waste from commercial nuclear power plants as the preferred long-term disposal option. By isolating wastes deep in underground caverns, these materials could be safely removed from contact with the biosphere. By the early 1960s, geologic storage becomes the accepted waste management strategy within the AEC. Electric utilities begin to invest in nuclear plants in the in mid-1960s, and the industry booms as the cost of fossil fuels skyrocket in response to the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973.[2] As a result, the amount of nuclear waste produced increases exponentially. In the 1970s and 1980s, nuclear agencies in France and around the world propose the idea of firing the waste into space in a rocket or putting it deep in the ocean. Both would be eventually rejected as too dangerous, with fears that a rocket could explode in the atmosphere and the radiation could leak into the ocean. In the 1990s, governments and scientists seem to have converged on the idea of burying the radioactive waste in storage facilities designed to last for ever.[3] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Scientific development | German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovers X rays.[4] | Germany |

| 1896 | Scientific development | French physicist Henry Becquerel identifies radioactivity.[5][6][7] | France |

| 1898 | Scientific development | French scientists Pierre and Marie Curie announce that they have identified a new element, radium, that has radioactive properties.[1] | France |

| 1928 | Organization | The International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC) is founded at the second International Congress of Radiology in Stockholm.[4] | Sweden |

| 1942 | Scientific development | The first self-sustaining nuclear reaction is created in a scientific facility at the University of Chicago.[8] | United States |

| 1945 | Background | The first successful test of atomic bomb takes place in Alamogordo, New Mexico. In the same year, the United States drops atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[8] | United States, Japan |

| 1946 | Organization | The United States Atomic Energy Commission is founded.[9][10][11] | United States |

| 1946 | Policy | A trefoil — three black blades on a yellow background — is created as the international warning symbol for radiation.[3] | |

| 1950 | Organization | The International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC) is restructured to take account of new uses of radiation outside the medical area, and is renamed International Commission on Radiological Protection.[4] | |

| 1955 – 1957 | Policy | The United States Atomic Energy Commission requests that the National Academy of Sciences consider the possibilities of disposing of high-level radioactive waste in quantity within the continental limits of the country. This request would lead to a conference at Princeton in 1955 and the subsequent 1957 report The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land. The problem posed to the National Academy of Sciences at that time is primarily the disposal of fission products from the reactors used in weapons manufacture.[2] | United States |

| 1956 | Power plant | Calder Hall, the first commercial nuclear power station for civil use, opens in Sellafield, England.[12] | United Kingdom |

| 1957 (July 29) | Organization | The International Atomic Energy Agency is established. It is an autonomous intergovernmental organization dedicated to increasing the contribution of atomic energy to the world’s peace and well-being and ensuring that agency assistance is not used for military purposes.[13][8][14] The IAEA is headquartered in Vienna. | |

| 1957 | Publication | The United States National Research Council publishes the report The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land, one of the first technical analyses of the geological disposal option. The publication marks the beginning of a four-decade effort by the national government to identify a disposal site for commercial spent fuel and defense waste (high-level waste).[2] | United States |

| 1957 | Storage | Extensive geological investigations start in Russia for suitable injection layers for radioactive waste, an approach that involves the injection of liquid radioactive waste directly into a layer of rock deep underground. Three sites are found, all in sedimentary rocks, at Krasnoyarsk, Tomsk, and Dimitrovgrad. In total, some tens of millions of cubic metres of low-level waste, intermediate-level waste and high-level waste would be injected in Russia.[15] | Russia |

| 1959 | The United States Atomic Energy Commission licenses commercial boats to haul 55-gallon drums filled with radioactive wastes out to sea, to be dumped overboard into deep water. Managers reason that the barrels would sink deeply enough that, even if they corroded or ruptured, the wastes would be sufficiently diluted in the ocean to pose no danger.[1] | United States | |

| 1961 | Facility | An International Atomic Energy Agency lab opens in Austria, creating a channel for cooperative global nuclear research.[8] | Austria |

| 1968 – 2002 | Approximately 47,000 tonnes of nuclear waste are produced in the period by commercial reactors in the United States.[16] | United States | |

| 1970 | Study | A study by the United States National Academy of Science, determines that the federal government should build a permanent geologic repository for high-level nuclear waste.[17] | United States |

| 1970s | Storage | In the United States, direct injection of about 7500 cubic metres of low-level waste as cement slurries is undertaken during the decade, at a depth of about 300 meters over a period of 10 years at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee. It would later be abandoned because of uncertainties over the migration of the grout in the surrounding fractured rocks (shales).[15] | United States |

| 1970s | Storage | The concept of deep borehole disposal of high-level radioactive waste is developed.[18] | |

| 1972 | Treaty | The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (generally known as the London Convention) is adopted. [19] | United Kingdom |

| 1977 | Organization | Germany’s Gesellschaft für Nuklear-Service mbH (GNS) is set up. Owned by the country's four nuclear utilities, is both an operator of waste storage and supplier of storage casks.[15] | Germany |

| 1978 | Facility | After five years of pilot plant operation, France's large AVM (Atelier de Vitrification Marcoule) plant starts up, turning cubic feet of concentrated high-level nuclear wastes into solid glass.[20][21][22] | France |

| 1979 | Organization | The Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Bau und Betrieb von Endlagern für Abfallstoffe mbH (DBE) (The German Society for the construction and operation of waste repositories) is founded and based in Peine. The company employs approximately 570 employees and is for 75% owned by the Gesellschaft für Nuklear-Service (GNS).[23] | Germany |

| 1979 | Crisis | The Three mile island accident is the worst accident in United States commercial reactor history. The accident is caused by a loss of coolant from the reactor core due to a combination of mechanical malfunction and human error. However, no one is injured, and no overexposure to radiation results from the accident.[12][24][8] | United States |

| 1980 | Organization | The Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, known as SKB) is created. It is responsible for final disposal of nuclear waste in the country. | Sweden |

| 1980 | The United States Department of Energy (DOE) proposes the use of mined geologic repositories as the most viable option for disposal of transuranic nuclear waste.[25] | United States | |

| 1980 | Swedish voters, concerned about the dangers of radiation and difficulties of waste disposal, vote in a referendum to close down all the country's nuclear reactors within 30 years and to consider a whole range of alternative sources of power.[20] | Sweden | |

| 1982 | Policy | The United States Congress passes the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA), which establishes the Federal government’s responsibility to provide permanent disposal in a deep geologic repository for spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste from commercial and defense facilities.[26] | United States |

| 1982 | Storage facility | The Lanyu storage site, a nuclear waste storage facility, is built at the Southern tip of Orchid Island in Taitung County, offshore of Taiwan Island. It is owned and operated by Taipower Company. The facility receives nuclear waste from Taipower's current three nuclear power plants. However, due to the strong resistance from local community in the island, the nuclear waste has to be stored at the power plant facilities themselves.[27][28] | Taiwan |

| 1982 | Policy | United States President Jimmy Carter, concerned about the possibility of nuclear proliferation, bans commercial reprocessing of spent fuel for private companies, leaving no long-term option for spent fuel storage and reprocessing available to utilities.[17][29] | United States |

| 1983 | Policy | A Nuclear Waste Policy Act requires the United States Department of Energy to start taking utilities’ spent fuel by Jan. 31, 1998. It directs DOE to begin studying sites for permanent repositories and establishes a schedule for that process.[17] | United States |

| 1985 | Sweden starts operating a radioactive waste sea transport system. A specially built ship, the M/S Sigyn, carries all radioactive waste between nuclear facilities and the national Central Interim Storage Facility for Spent Nuclear Fuel, located in Oskarshamn in southern Sweden.[30] | Sweden | |

| 1986 | Crisis | The Chernobyl disaster occurs after a safety test deliberately turns off safety systems. A large amount of radiation occurs, over fifty firefighter die, and up to 4,000 civilians are estimated to die of early cancer.[31] | Ukraine |

| 1987 | Policy | The United States Nuclear Waste Policy Act is amended to designate Yucca Mountain, located in the remote Nevada desert, as the sole national repository for spent fuel and high-level waste from nuclear power and military defence programs.[15] | United States |

| 1988 | Facility | The Swedish Final Repository for Radioactive Operational Waste (SFR) starts operations for disposal of low-level short-lived radioactive waste. The first of its kind in the world, in granite rock 50 meters (164 feet) below the Baltic Sea, the SFR is 60 meters offshore, connected by a tunnel to the site of the Forsmark nuclear power plant in central Sweden.[30] | Sweden |

| 1988 – 1990 | Study | In 1988, the United States Board on Radioactive Waste Management convenes a study session with experts from the United States and abroad to discuss U.S. policies and programs for managing the nation's spent fuel and high-level waste. In 1990, the board would publish report Rethinking High-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal, which provides a broad assessment of the technical and policy challenges for developing a repository for the disposition of high-level waste. The report notes that: “There is a strong worldwide consensus that the best, safest long-term option for dealing with HLW is geological isolation…. Although the scientific community has high confidence that the general strategy of geological isolation is the best one to pursue, the challenges are formidable.”[2] | United States |

| 1989 (March 22) | Treaty | The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal is signed. The agreement provides the general framework for the minimization of international movement and the environmentally safe management of hazardous wastes.[32][33][34] | Switzerland |

| 1991 (January 30) | Treaty | The Convention on the Ban of Imports into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa (Bamako Convention) is adopted by African governments in Bamako, Mali.[35][36][37] | Mali |

| 1992 | Facility | A near-surface disposal facility in cavern below ground level opens in Olkiluoto, Finland for low-level waste and intermediate-level waste.[15] | Finland |

| 1995 | Legal | A parliamentary waste commission report speaks of the "possible existence of national and international trafficking in radioactive waste, managed by business and criminal lobbies, which are believed to operate also with the approval of institutional subjects belonging to countries and governments of the European Union and outside the EU."[38] | |

| 1996 | Legal | The 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (known as the London Protocol) enters into force. Rather than stating which materials may not be dumped into the sea, the convention prohibits all dumping, except for possibly acceptable wastes.[19] | |

| 1997 | Treaty | The Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management takes place in Vienna as an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) treaty. It is the first treaty to address radioactive waste management on a global scale.[39][40] | Austria |

| 1997 | Facility | A near-surface disposal facility in cavern below ground level opens in Loviisa, Finland. The depth of this is about 100 meters.[15] | Finland |

| 1998 (April 22) | Treaty | The Bamako Convention comes into force.[41] | |

| 1999 | Facility | The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) becomes operational in New Mexico for defence transuranic wastes (long-lived intermediate-level waste).[15][42] | United States |

| 2000s | Storage | Dry cask storage is used in the United States, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Japan, Armenia, Argentina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, South Korea, Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine and Lithuania.[43] | United States, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Japan, Armenia, Argentina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, South Korea, Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine, Lithuania |

| 2002 | Storage | After over 30 years of scientific and technological studies, the United States President and Congress approve the Yucca Mountain site as suitable for a repository os nuclear waste.[26] | United States |

| 2006 | Facility | The KURT (Korea Underground Research Tunnel), a cave-type underground research facility, is constructed at the site of the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI), as part of the atomic energy R&D program in Korea. The KURT conducts research on deep geological repository for high-level radioactive wastes disposal.[44] | South Korea |

| 2009 | Facility | The Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (SKB) announces its decision to locate a mined repository at Östhammar (Forsmark).[15] | Sweden |

| 2011 | Organization | Magnox Ltd is founded as a nuclear waste company. It is responsible for the decommissioning of ten Magnox nuclear power stations in the United Kingdom.[45] | United Kingdom |

| 2013 | Publication | Documentary Journey to the Safest Place on Earth is released. It discusses the huge quantity of radioactive waste and spent fuel rods being stored at various locations on the planet. | |

| 2017 | Storage | France's Areva launches the NUHOMS Matrix advanced used nuclear fuel storage overpack, a high-density system for storing multiple spent fuel rods in canisters.[46] | France} |

| 2024 | Belgium builds a new type of nuclear reactor near Antwerp, powered by a particle accelerator, called Myrrha. This reactor is designed to produce 100 times less waste than traditional reactors and is seen as a potential tool in cancer treatment. It is expected to be safer, able to shut down in milliseconds, and will initially produce medical radioisotopes. The project, funded by the Belgian government and the EU, aims to be fully operational by 2036-2038. Myrrha could significantly reduce nuclear waste lifespan from 300,000 years to 300 years by transmuting waste, making it a pioneering effort in nuclear technology.[47] | Belgium |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of August 12, 2021.

| Year | "nuclear waste" |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 4 |

| 1960 | 41 |

| 1970 | 62 |

| 1980 | 1,990 |

| 1990 | 2,620 |

| 2000 | 4,600 |

| 2010 | 7,480 |

| 2020 | 9,080 |

Google Trends

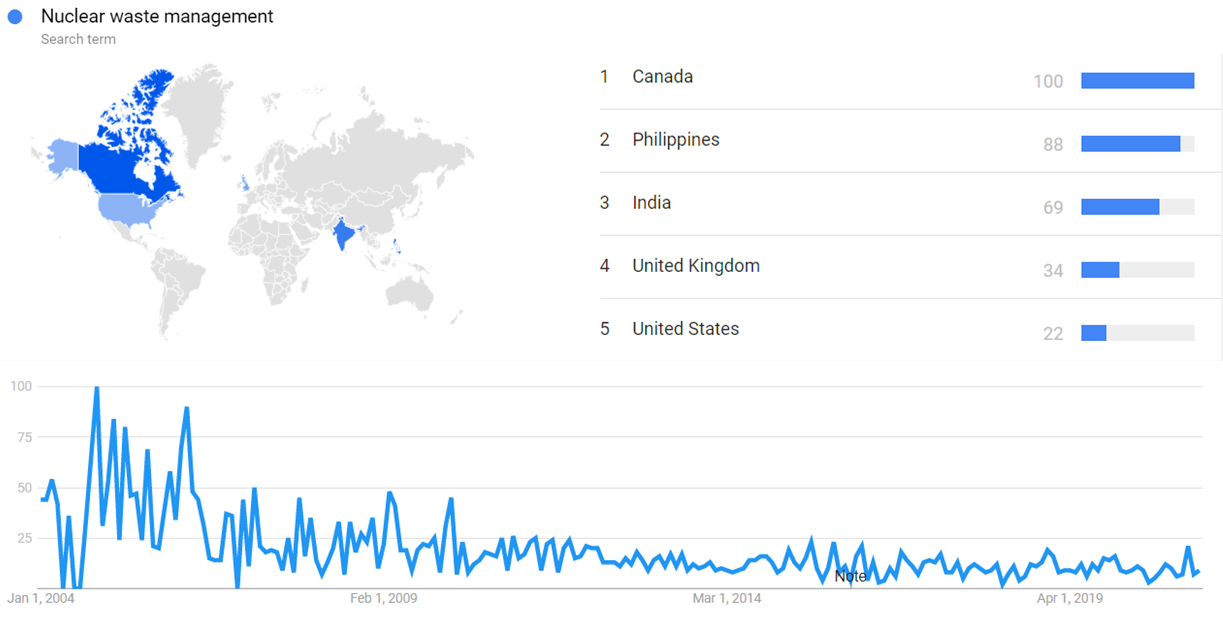

The image below shows Google Trends data for Nuclear waste management (Search term), from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[48]

Google Ngram Viewer

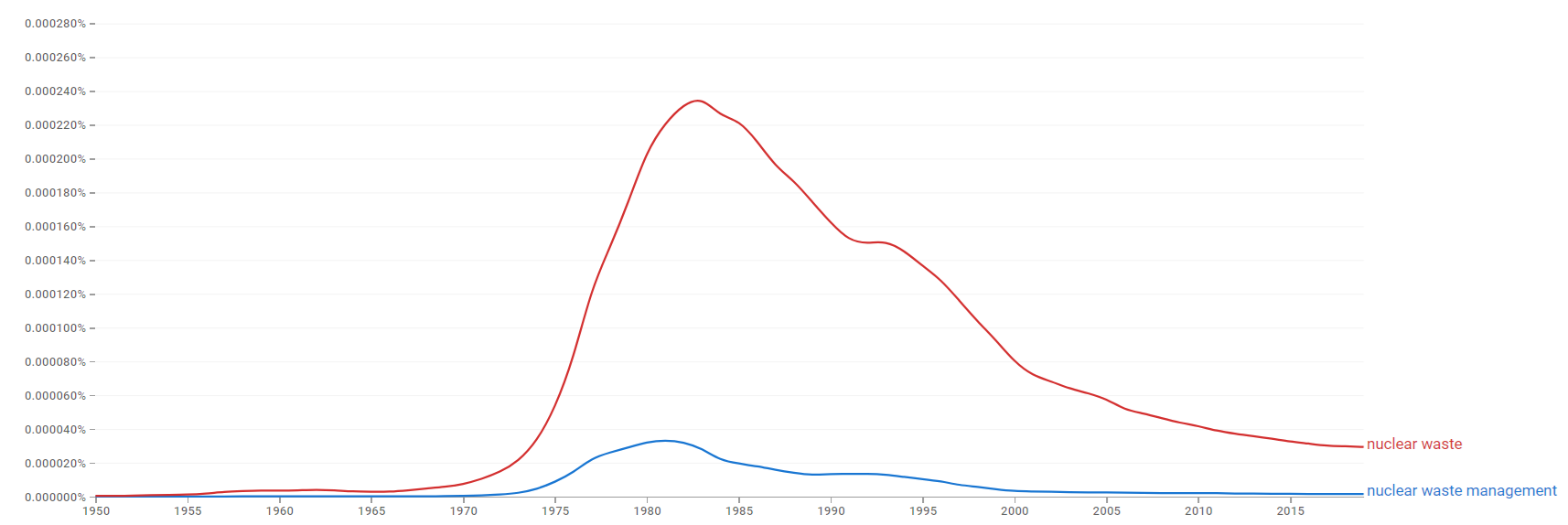

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for nuclear waste management and nuclear waste from 1950 to 2019.[49]

Wikipedia Views

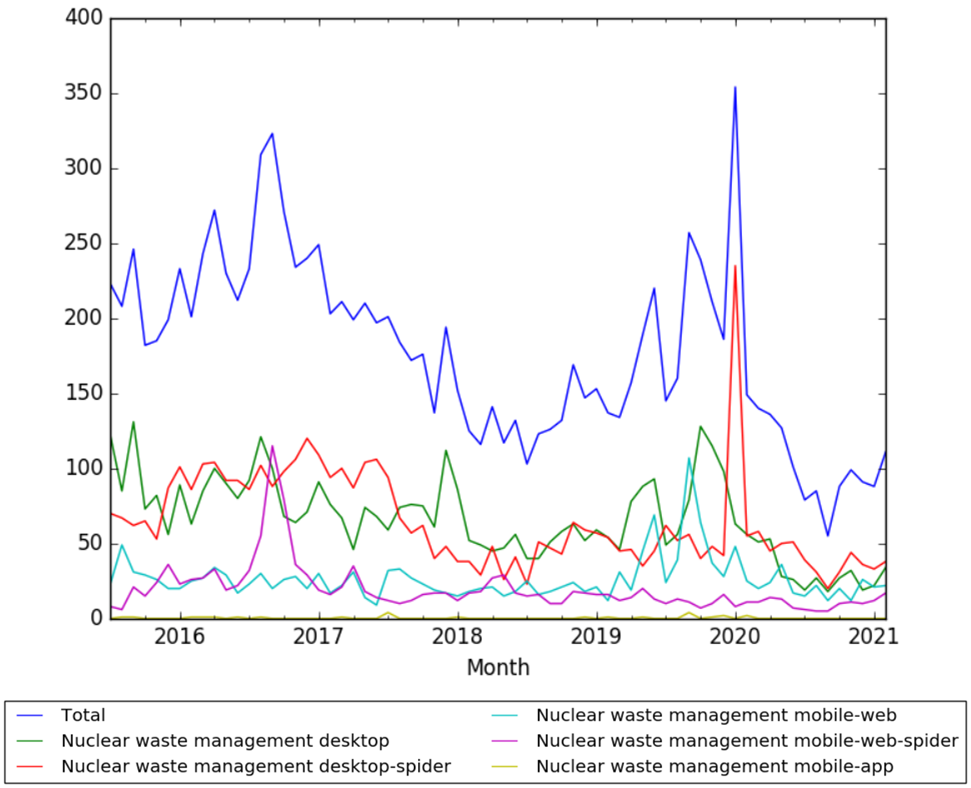

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Nuclear waste management, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to February 2021.[50]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "A history of the "Nuclear Waste" Issue". nucleargreen.blogspot.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Management of High-Level Waste: A Historical Overview of the Technical and Policy Challenges". nap.edu. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Nuclear waste: keep out for 100,000 years". ft.com. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Clarke, R.H.; J. Valentin (2009). "The History of ICRP and the Evolution of its Policies" (PDF). Annals of the ICRP. ICRP Publication 109. 39 (1): 75–110. doi:10.1016/j.icrp.2009.07.009. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Jayawardhana, Ray. The Neutrino Hunters.

- ↑ Francis, Charles. Light after Dark II: The Large and the Small.

- ↑ Russell, Peter J. Biology: The Dynamic Science, Volume 1 w/ PAC.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Olwell, Russell B. The International Atomic Energy Agency.

- ↑ "Atomic Energy Commission - 25 Year Anniversary (1971)". orau.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ Cleveland, Cutler J. Concise Encyclopedia of the History of Energy.

- ↑ Doyle, James. Nuclear Safeguards, Security and Nonproliferation: Achieving Security with Technology and Policy.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "History of nuclear power". corporate.vattenfall.com. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ "International Atomic Energy Agency". britannica.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "IAEA". iaea.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 "Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste". world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ Herbst, Alan M.; Hopley, George W. Nuclear Energy Now: Why the Time Has Come for the World's Most Misunderstood Energy Source.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "History of Nuclear Waste Policy". berniesteam.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "US seeks waste-research revival". nature.com. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter". imo.org. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL: BOLD INNOVATIONS ABROAD INSTRUCTIVE FOR U.S.". nytimes.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ Toumanov, I. N. Plasma and High Frequency Processes for Obtaining and Processing Materials in the Nuclear Fuel Cycle.

- ↑ Ojovan, Michael I. Handbook of Advanced Radioactive Waste Conditioning Technologies.

- ↑ "Änderung des Atomgesetzes wegen Asse". udo-leuschner.de. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "The History Of Nuclear Energy" (PDF). energy.gov. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "HIST 3770, Spring 2016: Nuclear West: Nuclear Waste and Utah". exhibits.usu.edu. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "NATIONAL NUCLEAR WASTE DISPOSAL PROGRAM". thenwsc.org. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "Premier reiterates promise of end to Lanyu nuclear waste storage". focustaiwan.tw. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Tao protest against nuclear facility". taipeitimes.com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing: U.S. Policy Development". everycrsreport.com. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Sweden's radioactive waste management program". U.S. Department of Energy. June 2001. Archived from the original on 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ↑ "History of Nuclear Energy". whatisnuclear.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ Coles, Richard; Lorenzon, Filippo. Law of Yachts & Yachting.

- ↑ Wolfrum, Rüdiger; WOLFRUM, R.; Matz, Nele. Conflicts in International Environmental Law.

- ↑ Sands, Philippe; Peel, Jacqueline; MacKenzie, Ruth. Principles of International Environmental Law.

- ↑ Sands, Philippe. Principles of International Environmental Law I: Frameworks, Standards, and Implementation.

- ↑ Kummer, Katharina. International Management of Hazardous Wastes: The Basel Convention and Related Legal Rules.

- ↑ Marr, Simon. The Precautionary Principle in the Law of the Sea: Modern Decision Making in International Law.

- ↑ Italian police close in on 'toxic' shipwreck, The Financial Times, October 21 2009

- ↑ "Results of Review Meetings". ns.iaea.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management". iaea.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "The Bamako convention". unenvironment.org. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "Waste Isolation Pilot Plant". energy.gov. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (May 2007). Management of recyclable fissile and fertile materials. OECD Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-92-64-03255-2. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Mid- Technical Field Trips". iah2018.org. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "It's all boiled down to this...". magnoxsites.com. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Areva's space-saving solution for used fuel storage". World Nuclear News. 29 September 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Reactor nuclear subcrítico producirá en un segundo energía para todo un año". DW. 25 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ↑ "Nuclear waste management". Google Trends. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "nuclear waste management and nuclear waste". books.google.com. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ "Nuclear waste management". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 25 March 2021.