Difference between revisions of "Timeline of brain preservation"

(→Tracking preservation quality: removed graph tracking largest preserved tissue / organ (integrated feedback from Mike Darwin)) |

(→Full timeline: major revision; integrated some feedback from Mike Darwin, notably adding some technological milestones) |

||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| − | ! Date !! Type !! Subtype !! Organisation or individual !! Event | + | ! Date !! Category !! Type !! Subtype !! Organisation or individual !! Event |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1773-04 || | + | | 1773-04 || cryonics || futurism || || {{W|Benjamin Franklin}} || In a letter to Jacques Dubourg, {{W|Benjamin Franklin}} says: "I wish it were possible ...to invent a method of embalming drowned persons, in such a manner that they might be recalled to life at any period, however distant; for having a very ardent desire to see and observe the state of America a hundred years hence, I should prefer to an ordinary death, being immersed with a few friends in a cask of Madeira, until that time, then to be recalled to life by the solar warmth of my dear country! But ... in all probability, we live in a century too little advanced, and too near the infancy of science, to see such an art brought in our time to its perfection ...".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Works_of_the_Late_Doctor_Benjamin_Franklin_(1793).djvu/233|title=Page:Works of the Late Doctor Benjamin Franklin (1793).djvu/233 - Wikisource, the free online library|website=en.wikisource.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1883-04-15 || technological development || cold || || Nitrogen is liquefied by {{W|Zygmunt Wróblewski}} and {{W|Karol Olszewski}} at the {{W|Jagiellonian University}}.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8SKrWdFLEd4C&pg=PA249|page=249|title=A Short History of the Progress of Scientific Chemistry in Our Own Times|author=Tilden, William Augustus |publisher=BiblioBazaar, LLC|year=2009|isbn=1-103-35842-1}}</ref> | + | | 1883-04-15 || cryogenics || technological development || cold || || Nitrogen is liquefied by {{W|Zygmunt Wróblewski}} and {{W|Karol Olszewski}} at the {{W|Jagiellonian University}}.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8SKrWdFLEd4C&pg=PA249|page=249|title=A Short History of the Progress of Scientific Chemistry in Our Own Times|author=Tilden, William Augustus |publisher=BiblioBazaar, LLC|year=2009|isbn=1-103-35842-1}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1968 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation || Ed Hope closes Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation after seeing it wouldn't turn a profit. The remaining patients are turn over to other organizations or to relatives.<ref name="SuspensionFailures">{{Cite web|url=https://www.alcor.org/Library/html/suspensionfailures.html|title=Suspension Failures - Lessons from the Early Days|website=www.alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1931-07 || cryonics || writing || fiction || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} reads Neil R. Jones' newly published story, "The Jameson Satellite",<ref name="regis87">{{cite book |title= Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly Over The Edge|last= Regis|first= Ed|authorlink=Ed Regis (author) |coauthors= |year= 1991|publisher= Westview Press|location= |isbn= 0-201-56751-2|page= |pages= 87–88|url= }}</ref>, in which a professor has his corpse sent into earth orbit where it would remain preserved indefinitely at near absolute zero (note: this is not scientifically accurate), until millions of years later, when, with humanity extinct, a race of mechanical beings discovers, revives, and repairs him by transferring his brain in a mechanical body.<ref name="RCWE">{{cite web | title = {{W| Robert Ettinger}} | publisher = Cryonics Institute | url = http://www.cryonics.org/bio.html#Robert_Ettinger | accessdate = May 24, 2009 | deadurl = yes | archiveurl = https://www.webcitation.org/6ASYHJ6M9?url=http://www.cryonics.org/bio.html#Robert_Ettinger | archivedate = September 5, 2012 | df = mdy-all }}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1950-05 || cryobiology || technological development || vitrification || Luyet, Gonzales || Luyet and Gonzales achieve successful vitrification of chicken embryo hearts using ethylene glycol.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gonzales|first=F.|last2=Luyet|first2=B.|date=1950-5|title=Resumption of heart-beat in chick embryo frozen in liquid nitrogen|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15426631|journal=Biodynamica|volume=7|issue=126-128|pages=1–5|issn=0006-3010|pmid=15426631}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1954-06 || cryobiology || science || nature || Smith et al. || Smith et al., demonstrate the ability of golden hamsters to recover and survive long term following freezing of ~60% of the water in their brains and the survival a full recovery of hamsters cooled to -5°C.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Parkes|first=A. S.|last2=Lovelock|first2=J. E.|last3=Smith|first3=A. U.|date=1954-06|title=Resuscitation of Hamsters after Supercooling or Partial Crystallization at Body Temperatures Below 0° C.|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/1731136a0|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=173|issue=4415|pages=1136–1137|doi=10.1038/1731136a0|issn=1476-4687}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1959-05 || cryobiology || technological development || vitrification || Lovelock, Bishop || Lovelock and Bishop discover the cryoprotective properties of dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO). Me2SO would subsequently become a mainstay of most experimental vitrification solutions used in organ preservation.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=LOVELOCK|first=J. E.|last2=BISHOP|first2=M. W. H.|date=1959-05|title=Prevention of Freezing Damage to Living Cells by Dimethyl Sulphoxide|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/1831394a0|journal=Nature|volume=183|issue=4672|pages=1394–1395|doi=10.1038/1831394a0|issn=0028-0836}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1960s || || || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation in Phoenix, Arizona is founded by Ed Hope (not the same as the California organization with similar name). Unlike the others, it would build its own capsules, horizontal units on wheels for easy transport. | + | | 1965-03 || cryobiology || technological development || cryoprotection || James Farrant || James Farrant shows that viable ice free cryopreservation of a highly organized tissue is possible and that eliminating ice formation, even at -79 °C, eliminates virtually all of the extensive mechanical (histological) and ultrastructural disruption observed with conventional cryoprotection and freezing of complex tissues.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=FARRANT|first=J.|date=1965-03|title=Mechanism of Cell Damage During Freezing and Thawing and its Prevention|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/2051284a0|journal=Nature|volume=205|issue=4978|pages=1284–1287|doi=10.1038/2051284a0|issn=0028-0836}}</ref> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1968-02 || cryonics || science || resuscitation || Ames, et al. || Ames, et al., discover the cerebral no-re-flow phenomenon which prevents adequate reperfusion of the brain after ~10 minutes of global cerebral ischemia and identifies this as the likely cause of failure to achieve brain resuscitation after 6-10 minutes of normothermic ischemia rather than the acute death of brain cells as the supposed cause.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ames|first=A.|last2=Wright|first2=R. L.|last3=Kowada|first3=M.|last4=Thurston|first4=J. M.|last5=Majno|first5=G.|date=1968-2|title=Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon.|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2013326/|journal=The American Journal of Pathology|volume=52|issue=2|pages=437–453|issn=0002-9440|pmc=PMC2013326|pmid=5635861}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1969-04-11 || cryonics || futurism || || Jerome White || Jerome White, one of the founders of the Bay Area Cryonics Society, proposes the use of specially engineered viruses to effect repair of cells that are damaged by freezing and compromised by aging.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=White|first=J. B.|date=1969-04-11|title=Viral Induced Repair of Damaged Neurons with Preservation of Long-Term Information Content,|url=https://alcor.org/Library/pdfs/White1969.pdf|journal=Second Annual Cryonics Conference|volume=|pages=|via=|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970-05-22 || cryobiology || science || theory || Peter Mazur || Peter Mazur publishes his “two factor theory” elucidating the basic mechanisms of freezing damage to living cells: solution effects injury and/or intracellular freezing. This insight facilitates more rational design of freezing and thawing protocols allowing the development of freezing techniques for animal embryos.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mazur|first=P.|date=1970-05-22|title=Cryobiology: the freezing of biological systems|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5462399|journal=Science (New York, N.Y.)|volume=168|issue=3934|pages=939–949|issn=0036-8075|pmid=5462399}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1971 || resuscitation || science || || Hossmann || Hossmann demonstrate possible recovery of the cat brain after complete ischemia for 1 hour. The field of cerebral resuscitation is born.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hossmann|first=K.-A.|last2=Lechtape-Grüter|first2=H.|date=1971|title=Blood Flow and Recovery of the Cat Brain after Complete Ischemia for 1 Hour|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000114515|journal=European Neurology|volume=6|issue=1-6|pages=318–322|doi=10.1159/000114515|issn=0014-3022}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1971-08 || cryonics || writing || journal || Manrise Technical Review || Fred and Linda Chamberlain begin publishing a bi-monthly technical journal, Manrise Technical Review and in 1972 they publish the first comprehensive technical manual of human cryopreservation procedures. This marks the beginning of a biomedically informed and rigorously scientific approach to cryonics. In this manual the Chamberlains suggest apoplication of the Farrant technique to cryonics patients.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chamberlain|first=FR|last2=Chamberlain|first2=LL|date=1972|title=Instructions for the Induction of Solid State Hypothermia|url=|journal=Manrise Corporation|location=La Canada, CA|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1973-03 || cryonics || || || Cryonics Society of New York || Fahy and Darwin publish the first technical case report documenting the procedures, problems and responses of a human patient (Clara Dostal) to cryoprotective perfusion and freezing. The report is severely critical of the way cryonics patients are being treated and suggests many reform and inprovements.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=MD|date=1973|title=Perfusion and freezing of a 60-year-old woman|url=http://www.lifepact.com/images/MTRV3N1.pdf|journal=Manrise Technical Review|volume=3(1)|pages=9-32|access-date=2010-08-31|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1975-07 || suspended animation || technological development || || Gerald Klebanoff || Gerald Klebanoff demonstrates recovery of dogs from total blood washout and profound hypothermia with no neurological deficit using a defined asanguineous solution. Klebanoff documents the critical importance of adequate amounts of colloid in the perfusate to prevent death from pulmonary edema.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Haff|first=R. C.|last2=Klebanoff|first2=G.|last3=Brown|first3=B. G.|last4=Koreski|first4=W. R.|date=1975-7|title=Asanguineous hypothermic perfusion as a means of total organism preservation|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1142760|journal=The Journal of Surgical Research|volume=19|issue=1|pages=13–19|issn=0022-4804|pmid=1142760}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1977-07 || cryonics || futurism || || Darwin || Darwin is the first to conceive of the idea of an autonomous, bioengineered cell repair and replacement device to reverse cryo-injury and aging, which he called the “anabolocyte”.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Darwin|first=MG|date=July/August 1977|title=The anabolocyte: a biological approach to repairing cryoinjury|url=http://www.nanomedicine.com/NMI/1.3.2.1.htm|journal=Life Extension Magazine: A Journal of the Life Extension Sciences|volume=1|pages=|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1978-07 || cryonics || technological adoption || || Cryovita Laboratories || Jerry Leaf of Cryovita Laboratories introduces the principles and equipment of extracorporeal medicine into cryonics with the cryopreservation of Samuel Berkowitz. This included the use the heart-lung machine, closed circuit perfusion, 40µ arterial filtration and sterile technique and Universal Precautions to protect the staff caring for the patient:<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Leaf|first=JD|date=March-April 1979|title=Cryonic Suspension of Sam Berkowitz,|url=|journal=Long Life Magazine|volume=|pages=30-35|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1981-03 || cryonics || writing || journal || Darwin, Bridge || Michael Darwin and Stephen Bridge begin publication of the monthly magazine Cryonics which, for the next 10 years, would be the principle vehicle for publication of technical and scientific papers in cryonics.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.alcor.org/CryonicsMagazine/archive.html|title=Cryonics Magazine|website=www.alcor.org|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1983-01 || cryonics || technological development || || Darwin, et al. || Darwin, et al. carry out an extensive study to evaluate the efficacy of a human cryopreservation protocol on whole mammals (rabbits). This research discloses extensive ultrastructural disruption of the brain even when freezing in the presence of 3 M glycerol is employed. This work also documentes the extremely adverse effects of prolonged cold ischemia on cryoprotective perfusion.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=1389|title=Cryoprotective perfusion and freezing of the ischemic and nonischemic cat|last=Darwin|first=M|last2=Leaf|first2=JD|date=|website=|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=1390|title=CRYONICS: Freezing Damage (Darwin) Part 2|website=www.cryonet.org|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=1391|title=CRYONICS: Freezing Damage (Darwin) Part 3|website=www.cryonet.org|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=1392|title=CRYONICS: Freezing Damage (Darwin) Part 4|website=www.cryonet.org|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=MG|last2=Leaf|first2=JD|date=1983-01|title=Tahoe Research Proposals|url=http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8301.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=|issue=30|pages=14|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://chronopause.com/index.php/2012/02/13/the-effects-of-cryopreservation-on-the-cat-part-1/|title=THE EFFECTS OF CRYOPRESERVATION ON THE CAT, Part 1|last=chronopause|website=CHRONOSPHERE|language=en-US|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://chronopause.com/index.php/2012/02/14/the-effects-of-cryopreservation-on-the-cat-part-2/|title=THE EFFECTS OF CRYOPRESERVATION ON THE CAT, Part 2|last=chronopause|website=CHRONOSPHERE|language=en-US|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://chronopause.com/index.php/2012/02/21/the-effects-of-cryopreservation-on-the-cat-part-3/|title=THE EFFECTS OF CRYOPRESERVATION ON THE CAT, Part 3|last=chronopause|website=CHRONOSPHERE|language=en-US|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1987-06 || cryonics || technological development || [[wikipedia:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation|extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]] || Leaf, Darwin, Hixon || Leaf, Darwin and Hixon develop a mobile [[wikipedia:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation|extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]] (ECMO) cart which is capable of providing acute, in-field extracorporeal life support and cooling providing the first truly adequate method of maintaining viability and achieving rapid induction of hypothermia in cryonics patients.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Leaf|first=Jerry D|last2=Hixon|first2=Hugh|last3=Hugh|first3=Mike|date=1987|title=Development of a mobile advanced life support system for human biostasis operations|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8703.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=8|issue=3|pages=23-40|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/Library/pdfs/AlcorCaseA1133.pdf|title=Cryonic suspension case report: A-1133|last=Darwin|first=Michael G.|last2=Leaf|first2=Jerry D.|date=|website=Alcor Life Extension Foundation|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=|last3=Hixon|first3=Hugh L.}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1987-06-08 || cryonics || technological adoption || [[wikipedia:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation|extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]] || || First use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support on a cryonics patient.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/Library/pdfs/AlcorCaseA1133.pdf|title=Cryonic suspension case report: A-1133|last=Darwin|first=M.|date=|website=|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1989-02 || cryonics || writing || textbook || Wowk, Darwin || Wowk and Darwin author the first comprehensive textbook on cryonics designed for use in recruiting new members to Alcor.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://cryoeuro.eu:8080/download/attachments/425990/AlcorReachingForTomorrow1989.pdf|title=Cryonics: Reaching for Tomorrow,|last=Wowk|first=B.|last2=Darwin|first2=M.|date=1990|website=Alcor Life Extension Foundation|location=Riverside, CA|isbn=101880209004|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2010-10-09}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990-06-09 || cryonics || quality assessment || || Alcor || First evaluation of viability in a cryonics patient using Na+/K+ ratio in the renal cortex demonstrating good tissue viability following application of the Alcor Transport Protocol, including rapid post-arrest in-field washout and rapid air transport of the patient to the cryoprotective perfusion facility.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/fried.html|title=Cryopreservation case report: Arlene Francis Fried, A-1049|last=Darwin|first=MG|date=|website=|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990-10 || cryobiology || technological development || re-warming || Ruggera, Fahy || Ruggera and Fahy demonstrate uniform radio frequency re-warming of vitrified solution in volumes compsarable to those of the rabbit kidney without thermal runaway and at rates of re-warming sufficient to inhibit devitrification in their model system.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ruggera|first=P. S.|last2=Fahy|first2=G. M.|date=1990-10|title=Rapid and uniform electromagnetic heating of aqueous cryoprotectant solutions from cryogenic temperatures|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2249450|journal=Cryobiology|volume=27|issue=5|pages=465–478|issn=0011-2240|pmid=2249450}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990-10 || cryobiology || science || vitrification || Fahy, et al. || Fahy, et al., publish first paper documenting the behavior of large volumes of vitrification solution with respect to fracture temperature, thermal gradient, cooling rate, ice nucleation and crystal growth as a preliminary step to avoid fracturing in vitrified organs and tissues and to prevent devitrification during re-warming.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=G. M.|last2=Saur|first2=J.|last3=Williams|first3=R. J.|date=1990-10|title=Physical problems with the vitrification of large biological systems|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2249453|journal=Cryobiology|volume=27|issue=5|pages=492–510|issn=0011-2240|pmid=2249453}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1992-02 || cryonics || technological adoption || [[wikipedia:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation|extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]] || || First application of [[wikipedia:extracorporeal membrane oxygenation|extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]] ECMO in the patient’s home followed by ~8 hours of continuous ECMO support prior to perfusion.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casereport9202.html|title=The Transport of Patient A-1312S|last=Henson|first=HK|date=|website=|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995-05-31 || cryobiology || science || cryoprotection || Darwin || Darwin, et al., demonstrate much improved ultrastructural preservation in the dog brain and preservation of vascular integrity after perfusion with 7.5 M glycerol and freezing to -100 °C.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Darwin|first=M.|last2=Russell|first2=S.|last3=Wakfer|first3=P.|last4=Wood|first4=L.|last5=Wood|first5=C.|date=1995-05-31|title=Effect of Human Cryopreservation Protocol on the Ultrastucture of the Canine Brain|url=|journal=BioPreservation, Inc|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Platt|first=C.|date=July 1995|title=New Brain Study Shows Reduced Tissue Damage|url=http://www.cryocare.org/index.cgi?subdir=&url=ccrpt4.html#BRAIN|journal=CryoCare Report|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000-07-15 || cryobiology || technological development || vitrification || Fahy, Kheirabadi || Fahy and Kheirabadi achieve permanent life support after perfusion of rabbit kidneys with 7.5 M a vitrification solution demonstrating for the first time that concentrations of cryoprotectant compatible with vitrification are tolerable without the loss of renal viability.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kheirabadi|first=B. S.|last2=Fahy|first2=G. M.|date=2000-07-15|title=Permanent life support by kidneys perfused with a vitrifiable (7.5 molar) cryoprotectant solution|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10919575|journal=Transplantation|volume=70|issue=1|pages=51–57|issn=0041-1337|pmid=10919575}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004-02 || cryobiology || technological development || vitrification || Fahy, et al. || Fahy, et al., develop several highly stable vitrification solutions using synthetic ice blockers which also have extremely low toxicity. It is possible to perfuse kidneys with 9+ molar vitrification solution (~60%) without loss of viability.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=Gregory M.|last2=Wowk|first2=Brian|last3=Wu|first3=Jun|last4=Paynter|first4=Sharon|date=2004-2|title=Improved vitrification solutions based on the predictability of vitrification solution toxicity|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14969679|journal=Cryobiology|volume=48|issue=1|pages=22–35|doi=10.1016/j.cryobiol.2003.11.004|issn=0011-2240|pmid=14969679}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010-05 || cryobiology || technological development || cryoprotection || Wowk, et al. || Creation of first synthetic ice blockers and their application to organ and tissue preservation to radically increase the stability of vitrification solutions.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Wowk|first=B.|last2=Leitl|first2=E.|last3=Rasch|first3=C. M.|last4=Mesbah-Karimi|first4=N.|last5=Harris|first5=S. B.|last6=Fahy|first6=G. M.|date=2000-5|title=Vitrification enhancement by synthetic ice blocking agents|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10860622|journal=Cryobiology|volume=40|issue=3|pages=228–236|doi=10.1006/cryo.2000.2243|issn=0011-2240|pmid=10860622}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010-07 || cryobiology || technological development || toxicity || Fahy, et al. || Fahy, et al., make significant advances in neutralizing cryoprotectant toxicity.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=Gregory M.|date=2010-7|title=Cryoprotectant toxicity neutralization|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19501081|journal=Cryobiology|volume=60|issue=3 Suppl|pages=S45–53|doi=10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.05.005|issn=1090-2392|pmid=19501081}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015-12-12 || cryonics || organisation || || CryoCare || CryoCare preserves their first patient.<ref name="CryoCareFirst"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017-03 || cryobiology || technological development || re-warming || Bischoff, et al. || Bischoff, et al., develop a novel technique of inductive heat re-warming using magnetic nanoparticles in the vasculature allowing for uniform re-warming of organs the size of rabbit kidneys at rates high enough to prevent devitrification of M-22 vitrification solution at a concentration compatible with kidney viability. The system is potentially applicable to larger organs, such as the human brain.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Manuchehrabadi|first=Navid|last2=Gao|first2=Zhe|last3=Zhang|first3=Jinjin|last4=Ring|first4=Hattie L.|last5=Shao|first5=Qi|last6=Liu|first6=Feng|last7=McDermott|first7=Michael|last8=Fok|first8=Alex|last9=Rabin|first9=Yoed|date=03 01, 2017|title=Improved tissue cryopreservation using inductive heating of magnetic nanoparticles|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28251904|journal=Science Translational Medicine|volume=9|issue=379|doi=10.1126/scitranslmed.aah4586|issn=1946-6242|pmc=PMC5470364|pmid=28251904}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012-03-22 || cryonics || || || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || Fred Chamberlain III, a co-founder of Alcor, becomes the first patient to be demonstrably preserved free of ice formation as would observe from CT scans in 2018. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || cryonics || quality assessment || scan || Darwin || M. Darwin publishes “Preliminary Evaluation of Alcor Patient Cryogenic CT Scans” analyzing three of the four available Alcor neuropatient CT scans. Darwin concludes that it is highly likely that Alcor patient A-1002 was possibly the first human cryonics patient to achieve essentially ice free brain cryopreservation.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://spaces.hightail.com/receive/qqSYgDnnI1|title=Preliminary Evaluation of Alcor Patient Cryogenic CT Scans|last=Darwin|first=Michael|date=|website=|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1936 || reanimatology || organisation || founding || Negovsky || Negovsky founds the first resuscitation research laboratory in the world. In 1986 his laboratory would be renamed Institute of Reanimatology of the USSR (since 1991 of the Russian) Academy of Medical Sciences. This marks the inception of both reanimatology (resuscitation medicine) and critical care medicine both of which would be crucial to the credibility of cryonics paradigm.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Safar|first=P.|date=2001-06|title=Vladimir A. Negovsky the father of 'reanimatology'|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11723996|journal=Resuscitation|volume=49|issue=3|pages=223–229|issn=0300-9572|pmid=11723996}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1940 || cryobiology || writing || book || Basil Luyet, Marie Pierre Gehino || Basil Luyet and Marie Pierre Gehino publish "[https://books.google.ca/books/about/Life_and_Death_at_Low_Temperatures.html?id=a3YMtAEACAAJ Life and Death at Low Temperatures]", the book which marks the beginning of cryobiology as a formal area of study. In this landmark work they document the survival of a wide variety of cells and some tissues after ultra-rapid cooling to -194.5°C providing that ice formation in the tissue is inhibited by vitrification due to the ultra-rapid cooling.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/716713726|title=Life and death at low temperatures|last=J.|first=Luyet, B.|date=1940|publisher=Biodynamica|oclc=716713726}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1940s || cryogenics || technological development || cold || || {{W|Liquid nitrogen}} becomes commercially available.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cooper|first=S M|last2=Dawber|first2=R P R|date=2001-4|title=The history of cryosurgery|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1281398/|journal=Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine|volume=94|issue=4|pages=196–201|issn=0141-0768|pmc=PMC1281398|pmid=11317629}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1947 || cryogenics || || || Polge, Smith, Parkes || {{W|Robert Ettinger}}, while in the hospital for his battle wounds, discovers {{W|Jean Rostand}} research in {{W|cryogenics}}.<ref name="CITimeline">{{Cite web|url=https://www.cryonics.org/ci-landing/history-timeline/|title=History/Timeline {{!}} Cryonics Institute|website=www.cryonics.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1948 || cryobiology || technological development || vitrification || || Polge, Smith and Parkes discover the cryoprotective effects of glycerol and publish a paper documenting the successful hatching of chicks from fowl sperm cryopreserved with glycerol.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=POLGE|first=C.|date=1951-06|title=Functional Survival of Fowl Spermatozoa after Freezing at −79° C.|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/167949b0|journal=Nature|volume=167|issue=4258|pages=949–950|doi=10.1038/167949b0|issn=0028-0836}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1948-03 || cryonics || writing || fiction || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} publishes the story [https://archive.is/20120801065253/http://www.cryonics.org/Trump.html The Penultimate Trump], in which the explicit idea of cryopreservation of legally dead people for future repair is promulgated. This story was written in 1947.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?80014|title=Title: The Penultimate Trump|website=www.isfdb.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960 || cryonics || writing || communication || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} expected other scientists to advocate for cryonics. Given that this still hasn't happened, Ettinger finally makes the scientific case for cryonics. He sends this to approximately 200 people whom he selected from ''Who's Who in America'', but got little response.<ref name="regis87"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960s || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation in Phoenix, Arizona is founded by Ed Hope (not the same as the California organization with similar name). Unlike the others, it would build its own capsules, horizontal units on wheels for easy transport. | ||

| − | Cryo-Care would not use cryoprotectants or perfusion with its patients but would only do straight freezes to liquid nitrogen temperature. These freezings would be advertised as being for cosmetic purposes rather than eventual reanimation, though the cryonics issue would naturally arise.<ref name="SuspensionFailures"/> | + | Cryo-Care would not use cryoprotectants or perfusion with its patients but would only do straight freezes to liquid nitrogen temperature. These freezings would be advertised as being for cosmetic purposes rather than eventual reanimation, though the cryonics issue would naturally arise. <ref name="SuspensionFailures"/> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1961 || cryobiology || technological development || cryoprotection || Lovelock, Bishop || By 1961 the work of Lovelock and Bishop is rapidly extended to other animal sperm, including human sperm, and glycerol is also shown to be an effective cryoprotectant for both red cells and many nucleated mammalian cells.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/1027485685|title=Biological effects of freezing and supercooling|last=Ursula|first=Smith, Audrey|oclc=1027485685}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1962 || reanimatology || writing || book || Vladimir A. Negovsky || Vladimir A. Negovsky publishes his landmark book, "Resuscitation and Artificial Hypothermia".<ref>{{Cite book|title=Resuscitation and Artificial Hypothermia (USSR)|last=Negovsky|first=Vladimir|publisher=Consultants Bureau|year=1962|isbn=|location=New York|pages=}}</ref><references><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Safar|first=Peter|date=2001-06|title=Vladimir A. Negovsky the father of ‘reanimatology’|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00356-2|journal=Resuscitation|volume=49|issue=3|pages=223–229|doi=10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00356-2|issn=0300-9572}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1962 || writing || non-fiction || Evan Cooper || Evan Cooper publishes "Immortality: Physically, Scientifically, Now" under the pseudonym Nathan Duhring.<ref name="cryonics9208">{{Cite journal|last=Perry|first=Michael|date=August 1992|title=Unity and Disunity in Cryonics|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics9208.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=13|issue=145|pages=5|via=}}</ref> He coins the immortal "freeze, wait, reanimate" slogan.<ref name="cryonet23124">{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=23124|title=Ev Cooper|website=www.cryonet.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref><ref name="EvCooperClassic">{{Cite web|url=https://www.biostasis.com/ev-coopers-cryonics-classic-published-online/|title=Ev Cooper's cryonics classic published online – Biostasis|language=en-US|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> | + | | 1962 || cryonics || writing || non-fiction || Evan Cooper || Evan Cooper publishes "Immortality: Physically, Scientifically, Now" under the pseudonym Nathan Duhring.<ref name="cryonics9208">{{Cite journal|last=Perry|first=Michael|date=August 1992|title=Unity and Disunity in Cryonics|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics9208.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=13|issue=145|pages=5|via=}}</ref> He coins the immortal "freeze, wait, reanimate" slogan.<ref name="cryonet23124">{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonet.org/cgi-bin/dsp.cgi?msg=23124|title=Ev Cooper|website=www.cryonet.org|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref><ref name="EvCooperClassic">{{Cite web|url=https://www.biostasis.com/ev-coopers-cryonics-classic-published-online/|title=Ev Cooper's cryonics classic published online – Biostasis|language=en-US|access-date=2019-01-21}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1962 || | + | | 1962 || cryonics || futurism || || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} || Ettinger privately publishes a preliminary version of ''The Prospect of Immortality'', in which he makes the case for cryonics.<ref name="regis87"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1962 || social || meeting || || About 20 people attend the first informal cryonics meeting.<ref name="cryonics9208"/> | + | | 1962 || cryonics || social || meeting || || About 20 people attend the first informal cryonics meeting.<ref name="cryonics9208"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1962 || social || || Evan Cooper || After the first cryonics meeting, Cooper and a few other individuals form the Immortality Communication Exchange (ICE), an informal, "special-interest group" for the "freeze and wait" idea that would later be known as cryonics.<ref name="cryonics9208"/> | + | | 1962 || cryonics || social || || Evan Cooper || After the first cryonics meeting, Cooper and a few other individuals form the Immortality Communication Exchange (ICE), an informal, "special-interest group" for the "freeze and wait" idea that would later be known as cryonics.<ref name="cryonics9208"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1963 || organisation || founding || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || During the conference, the {{W|Life Extension Society}}, the first cryonics organization, is founded by Evan Cooper. It would be situated in Washington, D.C.<ref name="EvCooperClassic"/> | + | | 1963 || cryonics || organisation || founding || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || During the conference, the {{W|Life Extension Society}}, the first cryonics organization, is founded by Evan Cooper. It would be situated in Washington, D.C.<ref name="EvCooperClassic"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1963-12-29 || social || conference || || The first cryonics conference happens.<ref name="cryonics9208"/><ref name="firstNewsletter">{{Cite web|url=http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/2011/01/19/the-first-cryonics-newsletter/|title=The First Cryonics Newsletter|last=Perry|first=Mike|date=2011-01-19|website=Evidence Based Cryonics|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161126064131/http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/2011/01/19/the-first-cryonics-newsletter/|archive-date=2016-11-26|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> | + | | 1963-12-29 || cryonics || social || conference || || The first cryonics conference happens.<ref name="cryonics9208"/><ref name="firstNewsletter">{{Cite web|url=http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/2011/01/19/the-first-cryonics-newsletter/|title=The First Cryonics Newsletter|last=Perry|first=Mike|date=2011-01-19|website=Evidence Based Cryonics|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161126064131/http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/2011/01/19/the-first-cryonics-newsletter/|archive-date=2016-11-26|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1964 || | + | | 1964 || cryonics || futurism || || {{W|Robert Ettinger}} || {{W|Robert Ettinger}}'s ''The Prospect of Immortality'' finally attracts attention of a major publisher, Doubleday, which sends a copy to [[wikipedia:Isaac Asimov|Isaac Asimov]]; Asimov says that the science behind cryonics is sound, so the book is published. The book becomes a selection of the Book of the Month Club and is published in nine languages. Ettinger becomes a media celebrity, discussed in many periodicals, television shows, and radio programs.<ref name="regis87"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1964-01 || writing || newsletter || || The first issue of the {{W|Life Extension Society}} Newsletter is published.<ref name="cryonics9208"/><ref name="firstNewsletter"/> | + | | 1964-01 || cryonics || writing || newsletter || || The first issue of the {{W|Life Extension Society}} Newsletter is published.<ref name="cryonics9208"/><ref name="firstNewsletter"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1965 || || || Karl Werner || Karl Werner coins the word "{{W|cryonics}}".<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory">{{Cite web|url=http://www.benbest.com/cryonics/history.html|title=A HISTORY OF CRYONICS|website=www.benbest.com|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | + | | 1965 || cryonics || || || Karl Werner || Karl Werner coins the word "{{W|cryonics}}".<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory">{{Cite web|url=http://www.benbest.com/cryonics/history.html|title=A HISTORY OF CRYONICS|website=www.benbest.com|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1965 || organisation || founding || Cryonics Society of New York || The Cryonics Society of New York (CSNY) is founded by {{W|Saul Kent}}, {{W|Curtis Henderson}} and Karl Werner. CSNY is a non-profit organisation contracting with the for-profit organisation Cryospan for cryonics freezing and storage.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2009/nov/07/cryonics-british-dads-army|title=The Dad's Army of British cryonics|last=Hattenstone|first=Simon|date=2009-11-07|work=The Guardian|access-date=2019-01-22|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> | + | | 1965 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryonics Society of New York || The Cryonics Society of New York (CSNY) is founded by {{W|Saul Kent}}, {{W|Curtis Henderson}} and Karl Werner. CSNY is a non-profit organisation contracting with the for-profit organisation Cryospan for cryonics freezing and storage.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2009/nov/07/cryonics-british-dads-army|title=The Dad's Army of British cryonics|last=Hattenstone|first=Simon|date=2009-11-07|work=The Guardian|access-date=2019-01-22|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1965-05-20 || || || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || Wilma Jean McLaughlin of Springfield, Ohio dies from heart and circulatory problems. Ev Cooper would fill a report the following day "The woman who almost became the first person frozen for a possible reanimation in the future died yesterday." The attempt to freeze her is abandoned. While reports on this event would vary, many would mention the lack of preparation, cooperation from various people, and explicit consent as obstacles to the freezing.<ref name="BedfordSuspension">{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/Library/html/BedfordSuspension.html|title=The First Cryonic Suspension|website=alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | + | | 1965-05-20 || cryonics || || || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || Wilma Jean McLaughlin of Springfield, Ohio dies from heart and circulatory problems. Ev Cooper would fill a report the following day "The woman who almost became the first person frozen for a possible reanimation in the future died yesterday." The attempt to freeze her is abandoned. While reports on this event would vary, many would mention the lack of preparation, cooperation from various people, and explicit consent as obstacles to the freezing.<ref name="BedfordSuspension">{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/Library/html/BedfordSuspension.html|title=The First Cryonic Suspension|website=alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1965-06 || organisation || || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || The {{W|Life Extension Society}} offers to freeze the first person for free: "The {{W|Life Extension Society}} now has primitive facilities for emergency short term freezing and storing our friend the large homeotherm (man). LES offers to freeze free of charge the first person desirous and in need of cryogenic suspension." No one would take them on their offer.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> | + | | 1965-06 || cryonics || organisation || || {{W|Life Extension Society}} || The {{W|Life Extension Society}} offers to freeze the first person for free: "The {{W|Life Extension Society}} now has primitive facilities for emergency short term freezing and storing our friend the large homeotherm (man). LES offers to freeze free of charge the first person desirous and in need of cryogenic suspension." No one would take them on their offer.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1965-10-30 || || || Dandridge M. Cole || Dandridge M. Cole suffers a fatal heart attack. Cole had read ''The Prospect of Immortality'' in 1963. In his more recent book, ''Beyond Tomorrow'', he had devoted several pages to the subject. He had expressed a wish to be frozen after death. After some delay a call was placed to Ettinger, who later would write, "I was consulted by long-distance telephone several hours after he died, but in the end the family did what was to be expected{{snd}}nothing."<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> | + | | 1965-10-30 || cryonics || || || Dandridge M. Cole || Dandridge M. Cole suffers a fatal heart attack. Cole had read ''The Prospect of Immortality'' in 1963. In his more recent book, ''Beyond Tomorrow'', he had devoted several pages to the subject. He had expressed a wish to be frozen after death. After some delay a call was placed to Ettinger, who later would write, "I was consulted by long-distance telephone several hours after he died, but in the end the family did what was to be expected {{snd}} nothing."<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1966 || organisation || founding || Immortalist Soceity || The Cryonics Society of Michigan (later renamed the Cryonics Association, and then, in 1985, the {{W|Immortalist Society}}) is founded with Ettinger elected as its president.<ref name="CorpSummary">{{Cite web|url=https://cofs.lara.state.mi.us/CorpWeb/CorpSearch/CorpSummary.aspx?ID=800832595&SEARCH_TYPE=1|title=Search Summary State of Michigan Corporations Division|website=cofs.lara.state.mi.us|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | + | | 1966 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Immortalist Soceity || The Cryonics Society of Michigan (later renamed the Cryonics Association, and then, in 1985, the {{W|Immortalist Society}}) is founded with Ettinger elected as its president.<ref name="CorpSummary">{{Cite web|url=https://cofs.lara.state.mi.us/CorpWeb/CorpSearch/CorpSummary.aspx?ID=800832595&SEARCH_TYPE=1|title=Search Summary State of Michigan Corporations Division|website=cofs.lara.state.mi.us|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1966 || organisation || founding || Cryonics Society of California || The Cryonics Society of California (CSC) is founded by Robert Nelson. CSC is a non-profit organisation contracting with the for-profit organisation Cryonic Interment for cryonics freezing and storage. | + | | 1966 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryonics Society of California || The Cryonics Society of California (CSC) is founded by Robert Nelson. CSC is a non-profit organisation contracting with the for-profit organisation Cryonic Interment for cryonics freezing and storage. Cryonics Interment would later be renamed General Fluidics by Robert Nelson and Marshal Neel.<ref name="SuspensionFailures"/><ref name="CorpSummary"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1966 || science || | + | | 1966 || cryobiology || science || paper || Kroener and Luyet || Kroener and Luyet observe fracturing in vitrified glycerol solutions.<ref name="IntermediateTemperatureStorage">{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/Library/html/IntermediateTemperatureStorage.html|title=Systems for Intermediate Temperature Storage for Fracture Reduction and Avoidance|website=alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kroener|first=C.|last2=Luyet|first2=B.|date=1966|title=Formation of cracks during the vitrification of glycerol solutions and disappearance of the cracks during rewarming|url=|journal=Biodynamica|volume=10|pages=47-52|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1966-04-22 || || || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation || An elderly woman (probably from Los Angeles{{snd}}never identified) who has been embalmed for two months and maintained slightly above-freezing temperature is straight-frozen.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> There is some thought of the cryonics premise of eventual reanimation, but within a year she would be thawed and buried by relatives.<ref>{{Cite book|title=We Froze the First Man|last=F. Nelson|first=Robert|last2=Stanley|first2=Sandra|publisher=Dell|year=1968|isbn=|location=New York|pages=17-20}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kraver|first=Ted|date=March 1989|title=Notes on the First Human Freezing|url=|journal=Cryonics|volume=|pages=11-21|via=}}</ref> | + | | 1966-04-22 || cryonics || || || Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation || An elderly woman (probably from Los Angeles{{snd}}never identified) who has been embalmed for two months and maintained slightly above-freezing temperature is straight-frozen.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/> There is some thought of the cryonics premise of eventual reanimation, but within a year she would be thawed and buried by relatives.<ref>{{Cite book|title=We Froze the First Man|last=F. Nelson|first=Robert|last2=Stanley|first2=Sandra|publisher=Dell|year=1968|isbn=|location=New York|pages=17-20}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kraver|first=Ted|date=March 1989|title=Notes on the First Human Freezing|url=|journal=Cryonics|volume=|pages=11-21|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1966-10-15 || science || paper || || The first paper showing recovery of brain electrical activity after freezing to | + | | 1966-10-15 || cryonics || science || paper || || The first paper showing recovery of brain electrical activity after freezing to −20 °C is published.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Adachi|first=C.|last2=Kito|first2=K.|last3=Suda|first3=I.|date=1966-10-15|title=Viability of Long Term Frozen Cat Brain In Vitro|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/212268a0|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=212|issue=5059|pages=268–270|doi=10.1038/212268a0|issn=1476-4687}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1967-01-12 || technological adoption || cryonics || Cryonics Society of California || {{W|James Bedford}} is the first human to be cryopreserved. | + | | 1967-01-12 || cryonics || technological adoption || cryonics || Cryonics Society of California || {{W|James Bedford}} is the first human to be cryopreserved. |

The freezing is carried out by affiliates of the newly-formed Cryonics Society of California: {{W|Robert Prehoda}}, author and cryobiological researcher; Dante Brunol, physician and biophysicist; and Robert Nelson, President of the Society. Also assisting is Bedford's physician, Renault Able. | The freezing is carried out by affiliates of the newly-formed Cryonics Society of California: {{W|Robert Prehoda}}, author and cryobiological researcher; Dante Brunol, physician and biophysicist; and Robert Nelson, President of the Society. Also assisting is Bedford's physician, Renault Able. | ||

| Line 166: | Line 240: | ||

6 days later, relatives would move Bedford to the Cryo-Care facility in Phoenix. Later, his son would store him, and finally on September 22, 1987, Bedford would be moved to Alcor.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/><ref name="AlcorCase">{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/cases.html|title=Alcor Cases|website=alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | 6 days later, relatives would move Bedford to the Cryo-Care facility in Phoenix. Later, his son would store him, and finally on September 22, 1987, Bedford would be moved to Alcor.<ref name="BedfordSuspension"/><ref name="AlcorCase">{{Cite web|url=https://alcor.org/cases.html|title=Alcor Cases|website=alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1968 || || || | + | | 1968 || cryobiology || technological development || cryoprotection || || Dog kidneys are cryopreserved using Farrant's technique resulting in no ice formation and with excellent structural preservation, and the ability to tolerate reperfusion with blood in the animal without immediate failure.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kemp|first=E.|last2=Clark|first2=P. B.|last3=Anderson|first3=C. K.|last4=Laursen|first4=T.|last5=Parsons|first5=F. M.|date=1968|title=Low temperature preservation of mammalian kidneys|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4893380|journal=Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology|volume=2|issue=3|pages=183–190|issn=0036-5599|pmid=4893380}}</ref> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1968 || cryonics || writing || non-fiction || Robert Nelson || Robert Nelson publishes the book ''We Froze the First Man'' telling the story of Bedford's cryopreservation. However, his description is largely inaccurate. A more accurate description would be written later on [https://alcor.org/Library/html/BedfordLetter.htm DEAR DR. BEDFORD (and those who will care for you after I do)].<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/434744|title=We froze the first man|last=Nelson|first=Robert F.,|date=1968|publisher=[Dell Pub. Co.]|oclc=434744}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1969 || cryonics || organisation || founding || {{W|American Cryonics Society}} || The Bay Area Cryonics Society is founded by two physicians, prominent allergist and editor of [[wikipedia:Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology|Annals of Allergy]], Dr. M. Coleman Harris, and Dr. Grace Talbot. It would be renamed to the {{W|American Cryonics Society}} in 1985.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://businesssearch.sos.ca.gov/CBS/SearchResults?SearchType=NUMBER&SearchCriteria=C0587199|title=Business Search - Business Entities - Business Programs {{!}} California Secretary of State|website=businesssearch.sos.ca.gov|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.americancryonics.org/|title=American Cryonics Society - Human Cryopreservation Services for the 21st Century|website=www.americancryonics.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1969 || cryonics || || || Evan Cooper || Cooper ends his involvement in cryonics. He feels overloaded and burned-out, and thinks cryonics is not going to be a viable option for himself for practical (political, social, economic) reasons and that he is not going to spend the time he had left trying to obtain the impossible. He is also concerned with the commercial and political aspects within cryonics.<ref name="cryonet23124"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || cryonics || science || || Hossmann, Sato || Hossmann and Sato demonstrate that, contrary to decades of biomedical dogma, it is possible to restore robust electrical activity and demonstrate evoked potentials in cat brains that had been subjected to 1 hour of normothermic ischemia. This marks the beginning of the debunking of 3-6 minute limit on brain viability under conditions of normothermic ischemia. It also shows that brain cells do not undergo autolysis after ~10 minutes of normothermic ischemia, a view that was commonly held by both many physicians and neurologists prior to this time.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hossmann|first=K. -A.|last2=Sato|first2=K.|date=1970|title=The effect of ischemia on sensorimotor cortex of cat|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf00316134|journal=Zeitschrift f�r Neurologie|volume=198|issue=1|pages=33–45|doi=10.1007/bf00316134|issn=0340-5354}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryonics Society of America || The Cryonics Society of America (CSA) is incorporated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The purpose of the CSA is to establish “standards and practices” of operations for all of the cryonics societies, to mandate validation of human freezing by requiring the submission of photographic proof along with a death certificate, and a description of the procedure used and the location where the patient was being stored (essentially establishing a registry of cryonics patients). It is also created to allow for the creation of a Scientific Advisory Board which would, in fact, formed in March of 1968. CSA itself never got off the ground due to noncompliance with the "standards and practices" by the Cryonics Society of California.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://appext20.dos.ny.gov/corp_public/CORPSEARCH.ENTITY_INFORMATION?p_token=7361B53D067A654A76A77C3D820968CE25ADADB428A2F2B69B4B1B434D5CDC52D3EF5B4A61760545D791DA3D1A8E4D7F&p_nameid=4A504BB578548E78&p_corpid=A70384D2E44B2C90&p_captcha=11476&p_captcha_check=7361B53D067A654A76A77C3D820968CE25ADADB428A2F2B69B4B1B434D5CDC527922A9872C775310E6F079882FB316C3&p_entity_name=cryonics%20society&p_name_type=A&p_search_type=BEGINS&p_srch_results_page=0|title=Informational Message|website=appext20.dos.ny.gov|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970-05-15 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryonics Society of California || Nelson moves the 4 patients from the Cryonics Society of California into an underground vault he recently had designed and build under the aegis of Cryonics Interment. The vault is located in Oakwood Cemetery in {{W|Chatsworth, Los Angeles}}.<ref name="SuspensionFailures"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1971 || cryonics || futurism || || Martin || Cryonics by neuropreservation is proposed.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Martin|first=George M.|date=1971|title=On Immortality: An Interim Solution|url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/404700/summary|journal=Perspectives in Biology and Medicine|language=en|volume=14|issue=2|pages=339–340|doi=10.1353/pbm.1971.0015|issn=1529-8795}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1971 (end of) - 1979-04 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryonics Society of California || 9 patients are thawed by the Cryonics Society of California. This would become known as the Chatsworth Scandal, because the patients were stored in an underground vault at a cemetery in Chatsworth.<ref name="SuspensionFailures"/> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1972 || cryonics || technological adoption || || Trans Time || A collaborative working group led by Trans Time President Art Quaife and consisting of Gregory Fahy, Peter Gouras, M.D., Fred and Linda Chamberlain and Mike Darwin begin working on a standardized protocol for the cryoprotection of cryonics patients. Quaife publishes the first results of this effort, a modification of Collins’ organ preservation solution for use as the carrier solution for Me2SO during cryoprotective perfusion. This marks the first attempt at creating a standardized, science-based human cryopreservation protocol.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Quaife|first=A.|date=1972|title=Recommended modification to Collins’ solution for use as the base perfusate for inducing SSH|url=|journal=Manrise Technical Review|volume=2|pages=3-9|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1972 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Trans Time || Trans Time, Inc., (TT) a cryonics service provider, is founded by Art Quaife, along with John Day, Paul Segall and other cryonicists. It is a for-profit organisation. It's initially a perfusion service-provider for the Bay Area Cryonics Society. They buy the perfusion equipment from Manrise Corporation.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> They would be the first to undertake the effort of clarifying legal issues around cryonics, and to actively market cryonics.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> The name "Trans Time" is inspired by Trans World Airlines, a prominent airline.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://hpluspedia.org/wiki/History_of_cryonics#Chatsworth_Scandal|title=History of cryonics - H+Pedia|website=hpluspedia.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://businesssearch.sos.ca.gov/CBS/SearchResults?SearchType=NUMBER&SearchCriteria=C0647293|title=Business Search - Business Entities - Business Programs {{!}} California Secretary of State|website=businesssearch.sos.ca.gov|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1972 || cryonics || || || {{W|Mike Darwin}} || {{W|Mike Darwin}} is the first full-time cryonics researcher. He would work at Alcor for a year.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistoryImmortalist">{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryonics.org/immortalist/november08/History.pdf|title=A History of Cryonics|last=Best|first=Ben|date=2008-11-08|website=Cryonics Institute|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130628112826/http://www.cryonics.org/immortalist/november08/History.pdf|archive-date=2013-06-28|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1972-01-12 || suspended animation || technological adoption || || Klebanoff || Klebanoff reports survival of the first human after blood washout and induction of profound hypothermia with full recovery of heath and normal mentation, Air Force Seargent Tor Olsen who, as of 2018, would still be alive and well.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Klebanoff|first=G.|last2=Hollander|first2=D.|last3=Cosimi|first3=A. B.|last4=Stanford|first4=W.|last5=Kemmerer|first5=W. T.|date=1972-1|title=Asanguineous hypothermic total body perfusion (TBW) in the treatment of stage IV hepatic coma|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5058015|journal=The Journal of Surgical Research|volume=12|issue=1|pages=1–7|issn=0022-4804|pmid=5058015}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

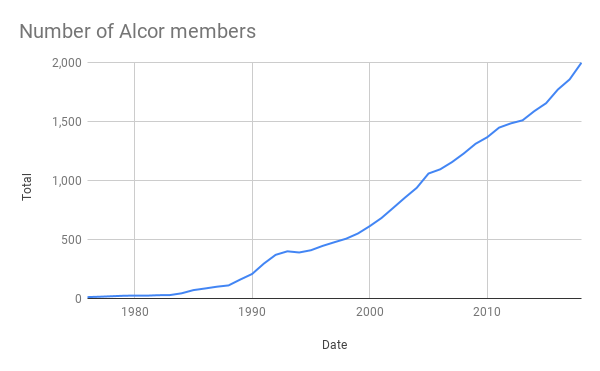

| − | | | + | | 1972-02-23 || cryonics || organisation || founding || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || The {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}}, a cryonics service provider, is founded by {{W|Fred and Linda Chamberlain}} in the State of California. The organisation is named after a star in the Big Dipper used in ancient times as a test of visual acuity. It would serve as a response team for the Cryonics Society of California. Alcor is initially incorporated as the Alcor Society for Solid State Hypothermia, but would change its name to the "{{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}}" in 1977.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://businesssearch.sos.ca.gov/CBS/SearchResults?SearchType=NUMBER&SearchCriteria=C0645886|title=Business Search - Business Entities - Business Programs {{!}} California Secretary of State|website=businesssearch.sos.ca.gov|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1973-08 || cryobiology || technological development || cryoprotection, re-warming || Hamilton, Lehr || Hamilton and Lehr demonstrate successful preservation of canine small intestine allografts using Me2SO as the cryoprotectant, and cooling and warming using vascular perfusion with helium gas suggesting that even controlled cooling and emptying of the vasculature's fluid/ice are beneficial in organ freezing. The organ is successfully transplanted.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=LaRossa|first=D.|last2=Hamilton|first2=R.|last3=Ketterer|first3=F.|last4=Lehr|first4=H. B.|date=1973-08|title=Preservation of structure and function in canine small intestinal autografts after freezing|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4722678|journal=Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery|volume=52|issue=2|pages=174–177|issn=0032-1052|pmid=4722678}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.journalofsurgicalresearch.com/action/captchaChallenge?redirectUri=%2Farticle%2F0022-4804%2873%2990033-4%2Fpdf|title=Journal of Surgical Research|website=www.journalofsurgicalresearch.com|doi=10.1016/0022-4804(73)90033-4|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1974 || cryonics || organisation || || Trans Time || Due to the closure of the storage facility in New York, the Bay Area Cryonics Society and the {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} change their plan to preserve their patients to the Trans Time facility instead of the New York one, and would do so until the 1980s.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1974 || cryonics || science || || || The first paper showing partial recovery of brain electrical activity after 7 years of frozen storage is published.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Suda|first=Isamu|last2=Kito|first2=Kyoko|last3=Adachi|first3=Chizuko|date=1974-04-26|title=Bioelectric discharges of isolated cat brain after revival from years of frozen storage|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0006899374902637|journal=Brain Research|volume=70|issue=3|pages=527–531|doi=10.1016/0006-8993(74)90263-7|issn=0006-8993}}</ref> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1974 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryonics Society of New York || {{W|Curtis Henderson}}, who has been maintaining three cryonics patients for the Cryonics Society of New York, is told by the New York Department of Public Health that he must close down his cryonics facility. The three cryonics patients are returned to their families, and would later be thawed.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1976 || cryonics || R&D || || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || Manrise Corporation provides initial funding to Alcor for cryonics research. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1976-04-28 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryonics Institute || Cryonics Institute is founded, and starts offering cryonics services: preparation, cooling, and long term storage.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://cofs.lara.state.mi.us/CorpWeb/CorpSearch/CorpSummary.aspx?ID=800830993&SEARCH_TYPE=1|title=Search Summary State of Michigan Corporations Division|website=cofs.lara.state.mi.us|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1976-07-16 || cryonics || technological adoption || || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || Alcor carries out the first human cryopreservation where cardiopulmonary support is initiated immediately post pronouncement and is continued until the patient is cooled to 15°C (~400 minutes) and where a scientifically designed custom perfusion machine with heat exchanger was used to carry out cryoprotective perfusion (as opposed to an embalming pump) with control over flow, pressure and temperature and incorporating a bubble trap was used. This is also the first neurocryopreservation (head only) patient. The patient was the father of Fred Chamberlain, the co-founder of the organisation.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chamberlain|first=FRC|last2=Chamberlain|first2=LLC|date=July 16-17, 1976|title=Alcor patient A-1001 Case Notes|url=|journal=Alcor Foundation|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref><ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistoryImmortalist"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1977 || cryonics || organisation || || Institute for Advanced Biological Studies || The Institute for Advanced Biological Studies (IABS) is incorporated by Steve Bridge. IABS is a nonprofit research startup.<ref name="IABS">{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=1981-03-08|title=The Newsletter of The Institute For Advanced Biological Studies, Inc.|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8103.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1977 || cryonics || organisation || || Soma, Inc. || Soma, Inc. is incorporated. Soma is intended as a for-profit organization to provide cryopreservation and human storage services. Its president is {{W|Mike Darwin}}. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1977 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryonics Institute || The Cryonics Institute preserves its first patient, Rhea Ettinger. She would be preserved in dry ice for 10 years, and then switch to liquid nitrogen. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1977(?) - 1986 || cryonics || social || || Life Extension Festival || The Life Extension Festival is run by {{W|Fred and Linda Chamberlain}}.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=July 1983|title=Report on the Lake Tahoe Life Extension Festival|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8307.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=|issue=36|pages=7-13|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1978 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Cryovita Laboratories || Cryovita Laboratories is founded by {{W|Jerry Leaf}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://businesssearch.sos.ca.gov/CBS/SearchResults?SearchType=NUMBER&SearchCriteria=C0849138|title=Business Search - Business Entities - Business Programs {{!}} California Secretary of State|website=businesssearch.sos.ca.gov|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref>, who had been teaching surgery at the {{W|University of California, Los Angeles}}. Cryovita is a for-profit organization which would provide cryopreservation services for Alcor and Trans Time in the 1980s.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1979 || cryonics || || || Institute for Advanced Biological Studies || Darwin et al., place the first long term storage marker animal into cryopreservation at the Institute for Advanced Biological Studies in Indianapolis, IN, using glycerol cryoprotection. This animal’s cephalon was subsequently transferred to Alcor where it remains in cryopreservation through the present. This was also the first cryopreservation of a companion animal, which was M. Darwin’s childhood dog “Mitzi”.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Darwin|first=M.|date=1979|title=Glycerol perfusion and extended storage of the canine central nervous system|url=|journal=Institute for Advanced Biological Studies, Inc|location=Indpls, IN|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1979 || cryonics || || || Institute for Advanced Biological Studies || The Institute for Advanced Biological Studies (IABS) puts Mitzi into cryopreservation, the first companion animal to receive the procedure. Alcor would later store the animal starting in 1982. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980 || cryonics || technological development || || Leaf et al. || Leaf et al., carry out the first closed circuit perfusions with stepped increase in cryoprotectant concentration under well controlled conditions with physiological and biochemical monitoring of the patients in real-time. This is also the first case where remote standby and stabilization using continuous heart-lung resuscitator support is carried out.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Leaf|first=JD|last2=Federowicz|first2=Hixon|last3=H.|first3=|date=38;1985|title=Case report: two consecutive suspensions, a comparative study in experimental human suspended animation|url=http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/casereport8511.html|journal=Cryonics|volume=6(11)|pages=13-38|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Life Extension Foundation || The Life Extension Foundation (LEF) is founded. It would later helped fund various cryonics organisations, notably Alcor, {{W|21st Century Medicine}}, Critical Care Research, and {{W|Suspended Animation, Inc}}.<ref name="BenBestCryonicsHistory"/> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980 || cryonics || organisation || founding || Institute for Cryobiological Extension || The Institute for Cryobiological Extension is founded, and would soon published its first volume of ICE Proceedings. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1981 || cryonics || futurism || || || The first paper suggesting that nanotechnology could reverse freezing injury is published.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Drexler|first=K. Eric|date=1981-09-01|title=Molecular engineering: An approach to the development of general capabilities for molecular manipulation|url=https://www.pnas.org/content/78/9/5275|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|language=en|volume=78|issue=9|pages=5275–5278|doi=10.1073/pnas.78.9.5275|issn=0027-8424|pmid=16593078}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1981 || cryonics || organisation || || Cryovita Laboratories || Soma, Inc. merges with Cryovita Laboratories. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1982 || cryobiology || science || toxicity || Fahy, et al. || Fahy, et al., publish papers which extensively documents the role of cryoprotectant toxicity as a barrier to tissue and organ cryopreservation suggest possible molecular mechanisms.<ref>{{Citation|last=Fahy|first=G. M.|title=Prospects for organ preservation by vitrification|date=1982|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-6267-8_60|work=Organ Preservation|pages=399–404|publisher=Springer Netherlands|isbn=9789401162692|access-date=2019-02-01|last2=Hirsch|first2=A.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=Gregory M.|last2=Lilley|first2=Terence H.|last3=Linsdell|first3=Helen|last4=Douglas|first4=Mary St.John|last5=Meryman|first5=Harold T.|date=1990-06|title=Cryoprotectant toxicity and cryoprotectant toxicity reduction: In search of molecular mechanisms|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0011-2240(90)90025-y|journal=Cryobiology|volume=27|issue=3|pages=247–268|doi=10.1016/0011-2240(90)90025-y|issn=0011-2240}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1982 || cryonics || organisation || || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || Alcor begins storing its own patients. It was previously storing its patients with Trans Time, Inc. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1982 || cryonics || organisation || || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || The Institute for Advanced Biological Studies merges with Alcor. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1982-09-15 || cryonics || social || || {{W|Society for Cryobiology}} || The {{W|Society for Cryobiology}} adopts new bylaws denying membership to organizations or individuals supporting cryonics.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://blog.ciphergoth.org/blog/2010/02/12/society-for-cryobiology-statements-on-cryonic/|title=Paul Crowley's Blog - Society for Cryobiology statements on cryonics|website=blog.ciphergoth.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.alcor.org/Library/html/coldwar.html|title=Cold War: The Conflict Between Cryonicists and Cryobiologists|website=www.alcor.org|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1983 || cryonics || organisation || || Institute for Cryobiological Extension || Leaf changes hats to President of the Institute for Cryobiological Extension (ICE) with the intention to devise a new project with the goal of having animal heads frozen, thawed, and reattached to a new body in such a way that would allow for neurocognitive evaluation. The project would later be deemed impractical. <ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=July 1983|title=Report on the Lake Tahoe Life Extension Festival|url=https://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8307.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=|issue=36|pages=7-13|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1984 || cryonics || science || || Darwin et al. || Darwin et al., publish the first paper documenting the effects of cryopreservation protocols on human patients. This paper documents the presence of extensive macro-tissue fracturing in all three patients examined and shows relatively good histological preservation in the patient treated with 3 M glycerol.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=M.|last2=Hixon|first2=H.|last3=Leaf|first3=J.|date=1984|title=Post-mortem examination of three cryonic suspension patients|url=http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8409.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=5|issue=9|pages=16-28|access-date=2010-08-31|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1984 || suspended animation || technological development || || Leaf, Darwin, Hixon || Leaf, Darwin and Hixon complete 3-years of research demonstrating successful 4-hour asanguineous perfusion of dogs at 5°C with full recovery of health, mentation and long term memory. The paper documenting this work is rejected by the Society for Cryobiology because the work was conducted by cryonicists. The perfusate developed during this research, MHP-2 continues to be used for total body washout through the present.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/tbwcanine.html|title=A mannitol-based perfusate for reversible 5-hour asanguineous ultraprofound hypothermia in canines (Report on work performed from 1984-87)|last=Leaf|first=JD|last2=Darwin|first2=M.|date=|website=1986|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2010-08-31|last3=Hixon|first3=H.}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1984 || cryobiology || science || paper || || The first paper showing that large organs can be cryopreserved without structural damage from ice is published.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=G. M.|last2=MacFarlane|first2=D. R.|last3=Angell|first3=C. A.|last4=Meryman|first4=H. T.|date=1984-08-01|title=Vitrification as an approach to cryopreservation|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0011224084900798|journal=Cryobiology|volume=21|issue=4|pages=407–426|doi=10.1016/0011-2240(84)90079-8|issn=0011-2240}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1984 || cryonics || science || observation || {{W|Alcor Life Extension Foundation}} || Alcor observes fractures in human cryopreservation patients. <ref name="IntermediateTemperatureStorage"/><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=M.|last2=Hixon|first2=H.|last3=Leaf|first3=J.|date=1984|title=Postmortem Examination of Three Cryonic Suspension Patients|url=https://alcor.org/Library/html/postmortemexamination.html|journal=Cryonics|volume=|pages=16-28|via=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1985 || cryonics || technological adoption || remote stabilization || || For the first time, a cryonics patient is given remote standby with in-field total body washout. Cardiopulmonary support (CPS) is initiated within 2 minutes following monitored cardiac arrest. This is also the first case where anesthesia is used to inhibit consciousness during cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) and external cooling.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=MG|last2=Leaf|first2=JD|last3=Hixon|first3=H.|date=1986|title=Case report: neuropreservation of Alcor patient A-1068 (1 of 2)|url=http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8602.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=7|issue=2|pages=17-32|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Federowicz|first=MG|last2=Leaf|first2=JD|last3=Hixon|first3=H.|date=1986|title=Case report: neuropreservation of Alcor patient A-1068 (2 of 2)|url=http://www.alcor.org/cryonics/cryonics8603.txt|journal=Cryonics|volume=7|issue=3|pages=15-29|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cryocare.org/index.cgi?subdir=bpi&url=tech21.txt|title=Securing anesthesia in the human cryopreservation patient|last=Darwin|first=M.|date=1997-01-18 16:38:31|website=CryoNet|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1985 || cryobiology || vitrification || vitrification || Fahy, Rall || Fahy and Rall successfully apply vitrification to embryo preservation introducing the technique to mainstream medicine and highlighting its potential utility in solid organ cryopreservation.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Rall|first=W. F.|last2=Fahy|first2=G. M.|date=1985 Feb 14-20|title=Ice-free cryopreservation of mouse embryos at -196 degrees C by vitrification|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3969158|journal=Nature|volume=313|issue=6003|pages=573–575|issn=0028-0836|pmid=3969158}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980s (mid) || cryonics || legal || || Jackson National || Jackson National is the first life insurance company to definitively state that it acknowledges that cryonics arrangements constitute a legitimate insurable interest.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://groups.yahoo.com/|title=Yahoo! Groups|website=groups.yahoo.com|language=en-US|access-date=2019-01-22}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980s (mid) || cryobiology || technological adoption || vitrification || {{W|Greg Fahy}} and William F. Rall || Researchers {{W|Greg Fahy}} and William F. Rall help introduce {{W|vitrification}} to reproductive cryopreservation. |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1986 || cryonics || writing || textbook || Darwin || M. Darwin publishes the first textbook on acute stabilization of human cryopreservation patients.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.alcor.org/Library/html/1990manual.html|title=Transport Protocol for Cryonic suspension of Humans|last=Darwin|first=MG|date=1986|website=Alcor Life Extension Foundation|location=Fullerton, CA|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1986 || cryobiology || science || vitrification || Fahy || Greg Fahy proposes vitrification as a mean of achieving viable parenchymatous organ preservation.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fahy|first=G. M.|date=1986|title=Vitrification: a new approach to organ cryopreservation|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3540994|journal=Progress in Clinical and Biological Research|volume=224|pages=305–335|issn=0361-7742|pmid=3540994}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

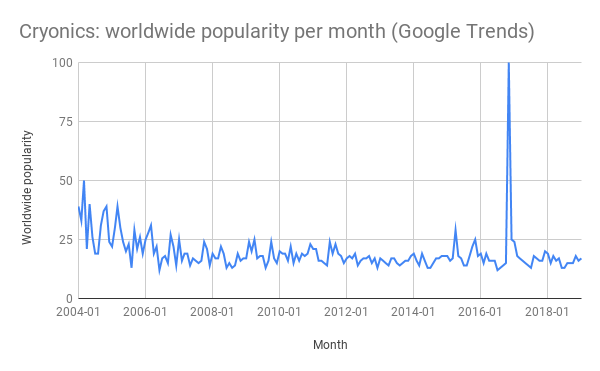

| − | | 1986 || | + | | 1986 || cryonics || futurism || || {{W|K. Eric Drexler}} || {{W|K. Eric Drexler}} publishes ''Engines of Creation''<ref>{{Cite book|title=Engines of creation|last=K. Eric|first=Drexler|publisher=Anchor Press/Doubleday|year=1986|isbn=0385199724|location=Garden City, N.Y|pages=}}</ref> -- the first book on molecular nanotechnology --. The book has a chapter on cryonics. It creates a surge in growth in cryonics interest and membership. |

|- | |- | ||