Timeline of healthcare in Bangladesh

This is a timeline of healthcare in Bangladesh.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1970s | Bangladesh gains independence, and starts implementing its Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI).[1] Access to modern medical facilities in rural areas remain very low. |

| 1980s | In the 1980s, Bangladesh has a basic healthcare infraestructure. However, most people in rural areas face critical health problems. The incidence of communicable disease is extensive, and there is widespread malnutrition, inadequate sewage disposal, and inadequate supplies of safe drinking water.[2] |

| 1990s | Bangladesh introduces its first National Health Policy, which proposes some drastic reforms of the health sector, to align with the suggestions of donors.[3] EHealth and mHealth activities are introduced in Bangladesh in the late 1990s.[4] |

| 2000s | The second National Health Policy is framed, suggesting several major institutional reforms, including the emphasis on client-centered reproductive health, cost-effective health service provision in a package called the Essential Service Package (ESP). |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | Organization (medical school) | Mymensingh Medical College is established.[5] | Mymensingh |

| 1940 | Policy | The Drugs Act, 1940 is introduced, regulating the import, export, manufacture, distribution and sale of pharmaceuticals in Bangladesh.[6] | |

| 1946 | Organization (medical school, hospital) | Dhaka Medical College and Hospital is established.[7] | Dhaka |

| 1957 | Organization (hospital) | A mental hospital is established at Pabna. Prior to this, there were no psychiatric services in Bangladesh.[8] | Pabna |

| 1957 | Organization (medical school) | Chittagong Medical College is established.[9] | Chittagong |

| 1958 | Organization (medical school) | Rajshahi Medical College is established.[7] | |

| 1962 | Organization (medical school) | Sir Salimullah Medical College is established.[7] | Dhaka |

| 1962 | Organization (medical school) | Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College is established.[7] | {Sylhet |

| 1969 | Organization (hospital) | The first outdoor clinic starts functioning in Dhaka Medical College.[8] | |

| 1969 | Organization (medical school) | Sher-e-Bangla Medical College is established.[7] | Barisal |

| 1970 | Organization (nursing school) | The Bangladesh College of Nursing is established. It is the only nursing college in the country.[10] | Dhaka |

| 1970 | Organization (medical school) | Rangpur Medical College is established.[11] | Rangpur |

| 1971 | Background | Bangladesh gains independence.[12] | |

| 1975 - 1980 | Program | Bangladesh starts to implement its Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI).[1] | |

| c.1979 | Statistics | An estimated 70% of the rural population do not have access to modern medical facilities.[2] | |

| 1980 | Organization (hospital) | The Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation for Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM) is founded.[13] | Dhaka |

| 1982 | Policy | A Drug Policy is formulated under the leadership of Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury.[3] The policy allows local pharmaceutical companies to acquire essential materials for producing drugs at home. Thanks to this, Bangladesh would become the first low-income country to develop a domestic pharmaceutical industry.[1][6] | |

| 1985 | Infrastructure | There are 341 functional subdistrict health centers, 1,275 rural dispensaries (to be converted to union-level health and family welfare centers), and 1,054 union-level health and family welfare centers. The total number of hospital beds at the subdistrict level and below is 8,100. Of the total country's 21,637 hospital beds in the mid-1980s, about 85% belong to the government health services, and there is only about one hospital bed for every 3,600 people.[2] | |

| 1986 (April) | Organization | A National Committe on AIDS is formed in the country, two years before an incidence of acquired immune deficiency is reported.[2] | |

| 1986 | Organization (medical school) | The Bangladesh Medical College is established.[14] | Dhaka |

| 1986 | Human capital | Bangladesh has about 16,000 physicians, 6,900 nurses, 5,200 midwives, and 1580 "lady health visitors", all registered by the government.[2] | |

| 1987 | Program | A national program to train and supervise traditional birth attendants (dhais) is started for maternal healthcare.[2] | |

| 1988 | Organization | The Bangladeshi government upgrades its nutrition policy-making capacity by creating the National Nutrition Council.[2] | |

| 1990 | Policy | The first National Health Policy is announced by the government of Hussain Muhammad Ershad. The policy proposes some drastic reforms of the health sector, to align with the suggestions of donors.[3] | |

| 1991 | Bangladesh has its first free election and General Ershad is forced to quit. The caretaker government of Shahabuddin Ahmed rescinds the National Health Policy, mostly under the pressure of health professionals. The new democratically elected regime led by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, attempts to formulate a new policy.[3] | ||

| 1992 | The Institute of Public Health produces tetanus vaccines.[6] | ||

| 1992 | Organization (medical school) | Comilla Medical College is established.[7] | Comilla |

| 1996 | The World Bank and other members of the donor consortium informs the government of Bangladesh that they would not proceed with further credits until a comprehensive, sector-wide strategy is adopted by the country. Including among their demands are substantive structural and organizational reforms of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.[3] | ||

| 1997 | Program | A Health and Population Sector Strategy (HPSS) is formulated under intense pressure from external donors.[3] | |

| 1997 - 2000 | In response to the poor public health system, prolific growth is observed in the private healthcare sector, with the number of private hospitals increasing from 288 to 613 in the period.[15] | ||

| 1998 | Organization (medical school) | Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University is established as the first postgraduate medical institution of the country.[16] | Dhaka |

| 1990s | The share of donor support to the total health sector is estimated at 25.8% in the decade.[3] | ||

| 2000 | Policy | The second National Health Policy is framed by the Bangladesh Awami League. It is closely influenced by the Health and Population Sector Strategy (HPSS), formulated earlier in 1997. The NHP2000 suggests several major institutional reforms, including the emphasis on client-centered reproductive health, cost-effective health service provision in a package called the Essential Service Package (ESP). The policy offers institutional facilities to the public sector doctors intending to do private practice, instead of banning it as in the 1990NHP.[3] | |

| 2001 | The World Health Organization approves oral cholera vaccine tested at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR-B).[6] | ||

| 2003 | Budget | The annual budget allocation for health is only 5.8% of the total government expenditure (compared with 18.5% in the United States and 15.8% in the United Kingdom).[15] | |

| 2003 | Organization | The The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is created, replacing previous funding mechanisms for Bangladesh's tuberculosis program.[17] | |

| 2006 | Organization (medical school) | Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College is established.[7] | Sher-e-Bangla Nagar |

| 2007 | Financial | The share of donor support to the total health sector is estimated at 8%.[3] | |

| 2010 | Recognition | Bangladesh receives a United Nations award for cutting the child mortality rate by two thirds well before the time frame set by the Millennium Development Goals.[1] | |

| 2011 | Policy | The National Health Policy is revised, introducing some new provisions but keeping the major policy objectives and strategies almost the same as in the NHP2000. Two major additions to the NHP2011 are: (1) emphasis on universal health coverage through health insurance and health cards, and (2) application of Information and communications technologies (ICT) in health service provision.[3] | |

| 2011-2012 | Human capital | Estimates show that Bangladesh has a total of 219,000 community health workers in the period, of which 56,000 come from the public sector.[1] | |

| 2012 | Policy | The Bangladeshi Government takes an initial step toward universal health coverage by developing health-financing strategies to raise funds through taxation and donor contributions.[18] | |

| 2012 | Campaign | On National Immunization Day, some 600,000 voluntary health workers are assembled at over 140,000 sites across Bangladesh with the aim to provide polio vaccines and vitamin A capsules to 24 million children.[1] | |

| 2012 | The 2012 Health Care Financing Strategy by the Government of Bangladesh outlines the roadmap to achieve universal health coverage by 2032. The goal of the strategy is to create one common pool of a universal Social Health Protection Scheme (SHPS).[19] | ||

| 2012 | Organization (hospital) | The National Institute of Neuroscience & Hospital is established.[20] | Dhaka |

Numerical and visual data

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 31, 2021.

| Year | healthcare in Bangladesh | private healthcare in Bangladesh | universal healthcare in Bangladesh | medicine in Bangladesh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 620 |

| 1985 | 19 | 8 | 4 | 749 |

| 1990 | 42 | 18 | 16 | 1,500 |

| 1995 | 135 | 72 | 43 | 1,710 |

| 2000 | 651 | 355 | 194 | 3,550 |

| 2002 | 883 | 553 | 294 | 4,070 |

| 2004 | 1,490 | 930 | 522 | 5,640 |

| 2006 | 2,140 | 1,380 | 811 | 7,230 |

| 2008 | 3,290 | 2,040 | 1,090 | 9,560 |

| 2010 | 4,630 | 2,820 | 1,670 | 13,000 |

| 2012 | 6,820 | 3,950 | 2,330 | 18,300 |

| 2014 | 9,650 | 5,330 | 3,070 | 26,400 |

| 2016 | 11,900 | 6,440 | 3,740 | 30,100 |

| 2017 | 13,100 | 7,110 | 4,090 | 32,100 |

| 2018 | 15,000 | 7,910 | 4,730 | 33,000 |

| 2019 | 17,200 | 8,660 | 5,180 | 33,300 |

| 2020 | 23,000 | 11,200 | 5,990 | 33,400 |

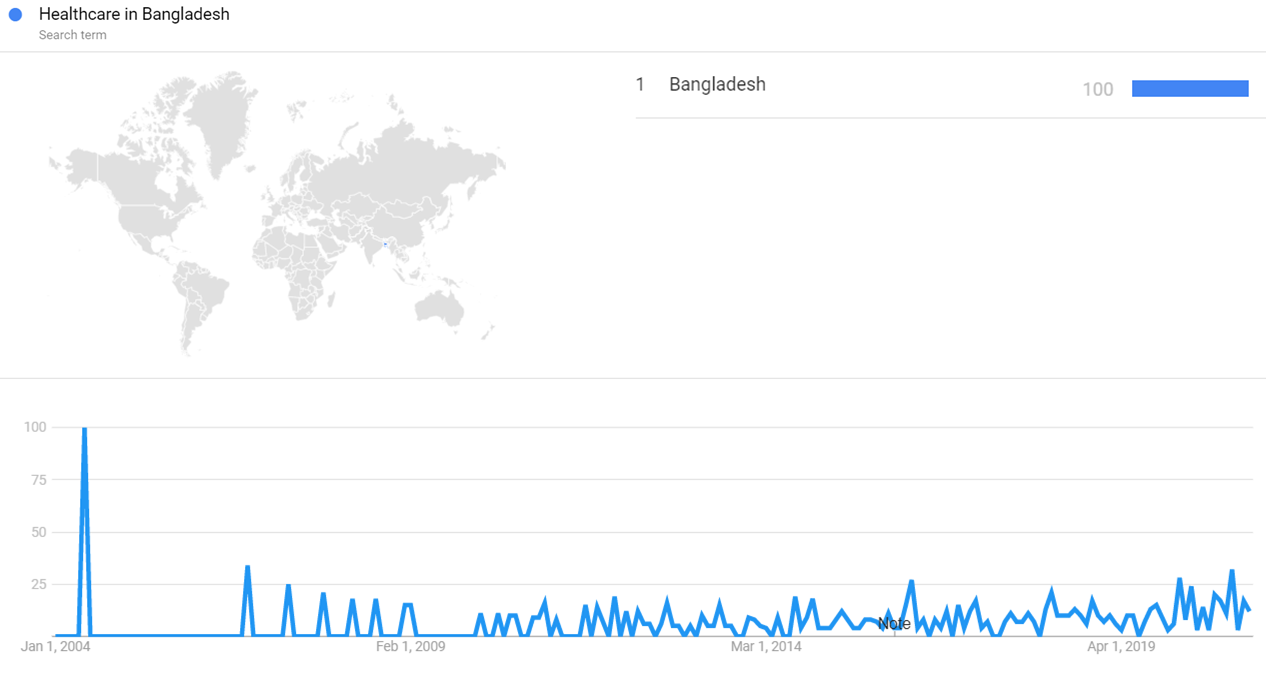

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data for Healthcare in Bangladesh (Search term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[21]

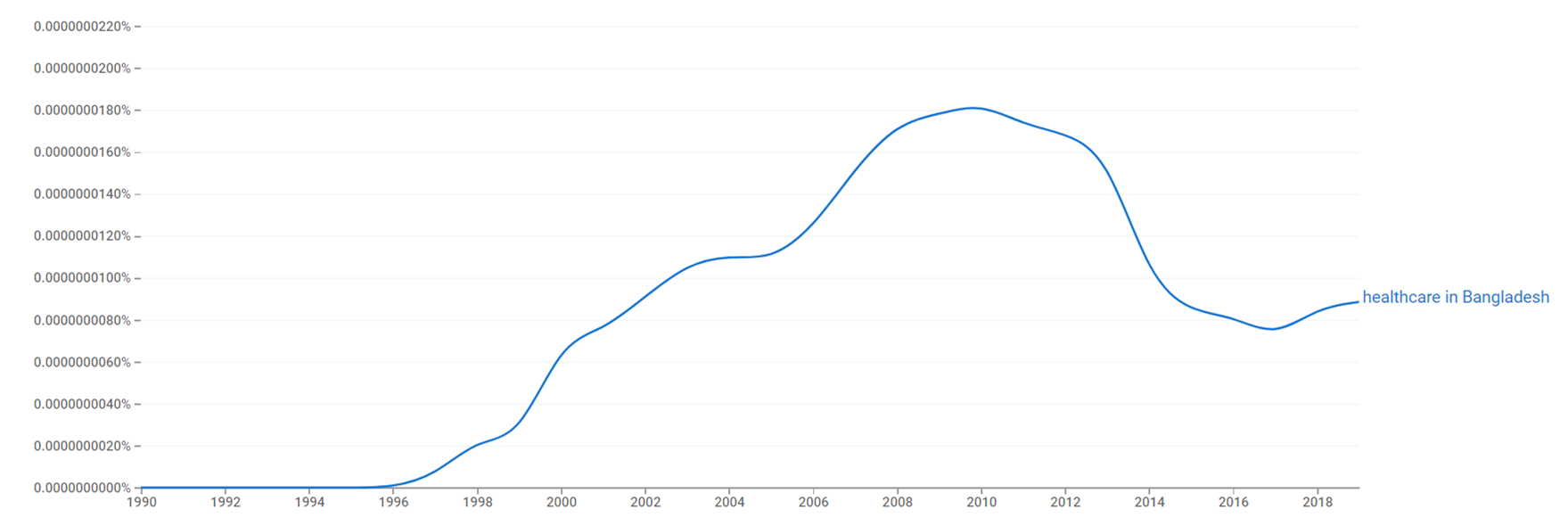

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Healthcare in Bangladesh from 1990 to 2019.[22]

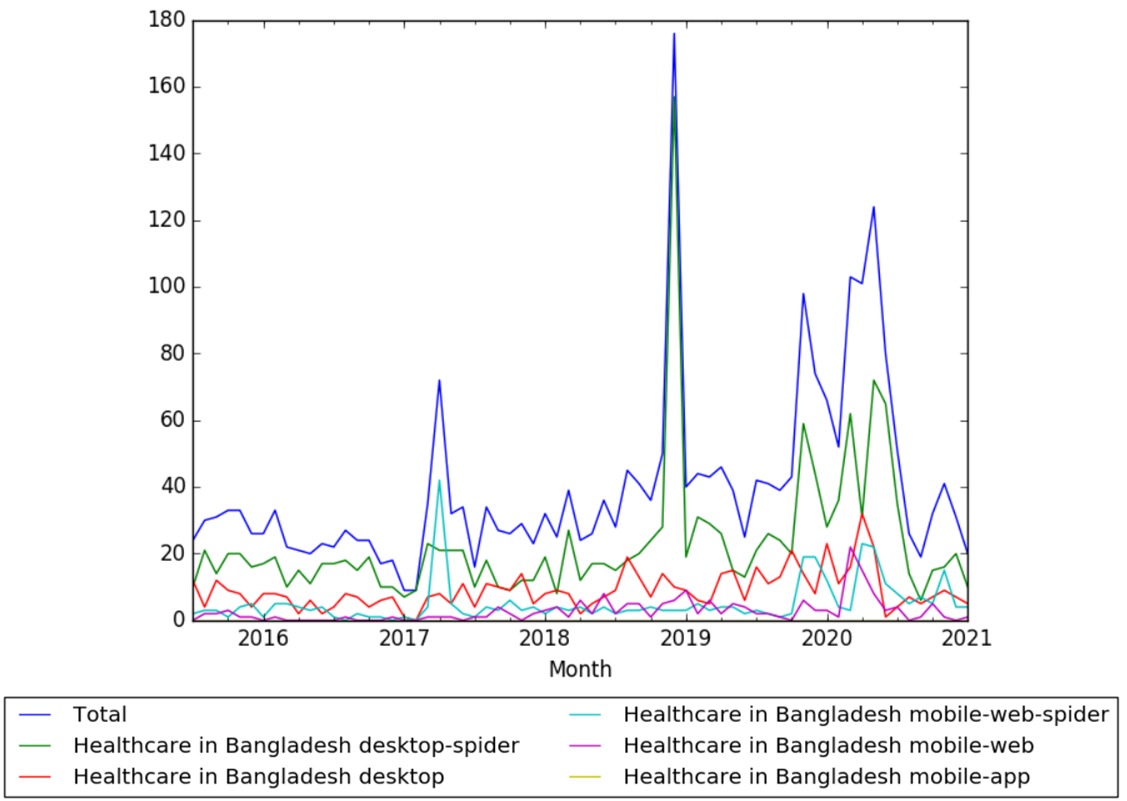

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Healthcare in Bangladesh on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider,mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.[23]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Riaz, Ali; Rahman, Mohammad Sajjadur. Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Bangladesh.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Bangladesh Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. IBP USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Ahmed, Nizam. Public Policy and Governance in Bangladesh: Forty Years of Experience.

- ↑ "Making healthcare accessible in Bangladesh". idrc.ca. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Mymensingh Medical College:". mmc.gov.bd. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Azam, Monirul. Intellectual Property and Public Health in the Developing World.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 "Medical College". retinabd.com. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mental Health Atlas 2005. By World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Mental Health: Evidence and Research, World Health Organization, World Health Organization. Mental Health Evidence and Research Team.

- ↑ "CHITTAGONG MEDICAL COLLEGE HOSPITAL". electives.net. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "Bangladesh College of Nursing". banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "RANGPUR MEDICAL COLLEGE, RANGPUR". education.bangladeshinformation.info. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "Universal health care in Bangladesh—promises and perils". thelancet.com. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ↑ "National Professor Dr Muhammad Ibrahim: A pioneer in diabetic care in Bangladesh". theindependentbd.com. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "Bangladesh Medical College". bmc-bd.org. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Islam, M. Saiful. Culture, Health and Development in South Asia: Arsenic Poisoning in Bangladesh.

- ↑ "Welcome to BSMMU". bsmmu.edu.bd. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Riaz, Ali; Sajjadur Rahman, Mohammad. Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Bangladesh.

- ↑ Rahman, Shafiur; Rahman, Mizanur; Gilmour, Stuart; Thet Swe, Khin; Krull Abe, Sarah; Shibuya, Kenji. "Trends in, and projections of, indicators of universal health coverage in Bangladesh, 1995–2030: a Bayesian analysis of population-based household data". doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30413-8.

- ↑ El-Saharty, Sameh; Powers Sparkes, Susan; Barroy, Helene; Ahsan, Karar Zunaid; Masud Ahmed, Syed. The Path to Universal Health Coverage in Bangladesh: Bridging the Gap of Human Resources for Health.

- ↑ "National Institute of Neurosciences & Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh". nins.com.bd. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "Healthcare in Bangladesh". Google Trends. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "Healthcare in Bangladesh". books.google.com. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ s.php?page=Healthcare+in+Bangladesh&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all "Healthcare in Bangladesh" Check

|url=value (help). wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 24 February 2021.