Timeline of Bay Area Rapid Transit

This is a timeline of Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), a mass rapid transit system serving the San Francisco Bay Area.

Contents

Big picture

| Period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Before 1945 | The idea of the Transbay Tube has been floated, and there has been some discussion of improving Bay Area transit options, but no concrete steps. |

| 1945–1957 | A series of statutes, commissions/working groups, and reports paves the way for the concept of and initial funding for a publicly funded, grade-separated, mass rapid transit system. |

| 1957–1964 | The initial years of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BARTD) involve a successful public relations campaign to secure large-scale funding and a full-fledged system plan. BARTD also successfully weathers the first lawsuit against it. |

| 1964–1972 | This is the period between the beginning of BART construction and the opening of the first BART line for passenger use. The period involves the construction of the Transbay Tube, Berkeley Hills Tunnel, Oakland Wye, Market Street Subway, and the rest of the initial BART system. |

| 1972–1978 | The initial batch of BART stations opens up, and BART increases its service hours, expands service to weekends, and increases the length of trains over this period. The last station to open up in this batch is Embarcadero, one of only two infill stations in the BART system, and also the most heavily used BART station. The period is marked by considerable criticism of BART for its poor safety procedures and below-expectations ridership, the latter stemming from below-expectations service frequency, low reliability, and safety concerns. Research shows that BART primarily displaces bus traffic and has little effect on automobile traffic, and its main value-add is for transbay riders. |

| 1985–2003 | BART works to relieve pressure at its southwest terminus of Daly City, and extend service further south. After a Daly City Turnback Extension Project (1985 onward), and construction of Colma station (opened 1995), BART expands service to South San Francisco, San Bruno, the San Francisco International Airport, and Millbrae (where it connects with Caltrain). |

| 1991–1997 | Over this period, BART constructs the Dublin/Pleasanton and Pittsburg extensions, opening the stations of Castro Valley and (East) Dublin/Pleasanton on the former and the stations of North Concord/Martinez and Pittsburg/Bay Point on the latter. |

| 2004–2012 (preparation starts in 2001) | BART works with major cellular carriers to extends cellular connectivity throughout the underground portion of the BART system. |

| 2009–present | BART extends service south of Fremont, with the ultimate goal of going all the way to San Jose. Multiple delays in financing, construction, and technical aspects of operations delay the opening of Warm Springs/South Fremont to March 2017. |

| 2011–present | BART begins work on the East Contra County Extension Project, which adds diesel eBART service extending east from the Pittsburg/Bay Point BART terminus. The first set of new stations opens for revenue service in May 2018. |

Fare schedule changes over time

| Year | Month and date | Minimum fare | Excursion fare | Percentage increase in fares | Date of approval of series of increases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | January 1 | 1.25. | 4.40 | ?? | ?? |

| 2006 | January 1 | 1.40 | ?? | 3.7% | May 2003 |

| 2008 | January 1 | 1.50 | 4.90 | ?? | May 2003 |

| 2009 | July 1 | 1.50 | 5.20 | 6.1% | May 2003 |

| 2012 | July 1 | 1.75 | 5.25 | 1.4% | May 2003 |

| 2014 | January 1 | 1.85 | 5.55 | 5.2% | February 2013 |

| 2016 | January 1 | 1.95 | 5.75 | 3.4% | February 2013 |

| 2018 | January 1 | 2.00 | 5.75 | 2.7% | February 2013 |

| 2020 | January 1 | 2.10 | 6.20 | 5.4% | February 2013 |

| 2022 | January 1 | ?? | ?? | ?? | ?? |

| 2024 | January 1 | ?? | ?? | ?? | ?? |

| 2026 | January 1 | ?? | ?? | ?? | ?? |

Visual data

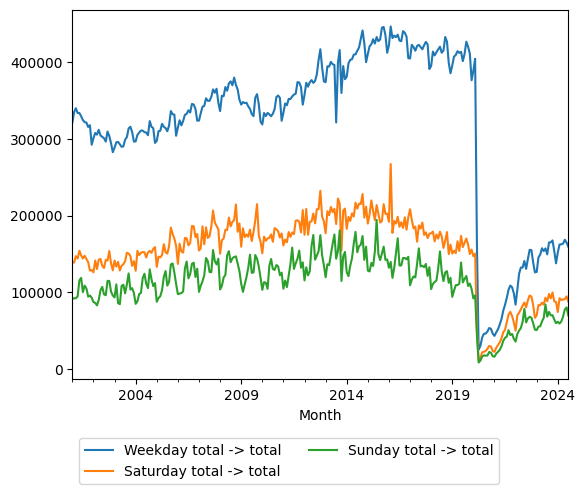

Overall ridership

The image below shows BART average weekday, Saturday, and Sunday ridership by month from January 2001 to March 2018. Traffic is highest on weekdays, lower on Saturdays, and even lower on Sundays. The referenced source will update the graph every month; the version shown below does not auto-update.[1]

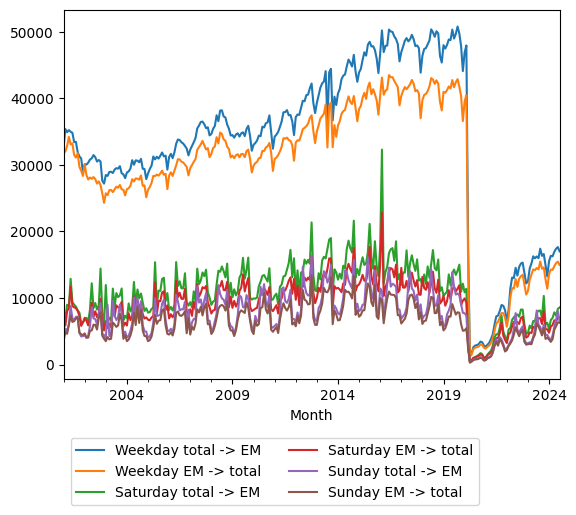

Ridership to Embarcadero, the busiest station

The image below shows BART ridership to and from Embarcadero: average weekday, Saturday, and Sunday ridership values by month from January 2001 to May 2017. Traffic is highest on weekdays, lower on Saturdays, and even lower on Sundays. Traffic to Embarcadero is a little higher than traffic from Embarcadero for any given month and day type, but differences between type of day dominate entry/exit differences. The referenced source will update the graph every month; the version shown below does not auto-update.[2]

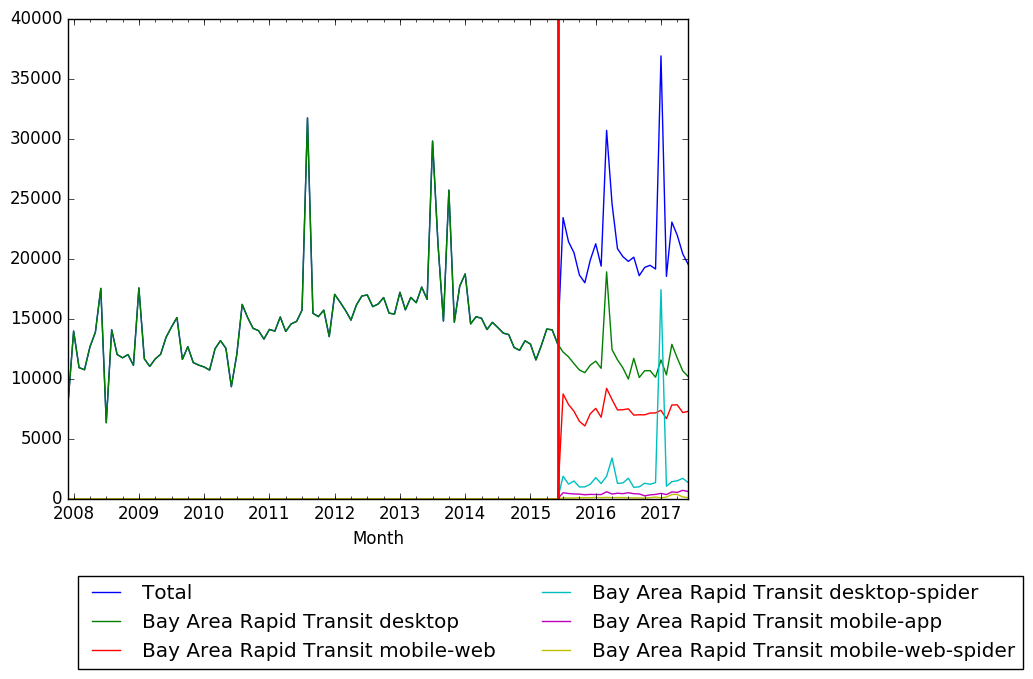

Wikipedia pageviews

The image below shows pageviews of the Wikipedia page Bay Area Rapid Transit from December 2007 to June 2017 on desktop, and from July 2015 to June 2017 on mobile web, mobile app, desktop spider, and mobile web spider. The image will not auto-update with data for new months; you can visit the source page to get up-to-date data.[3]

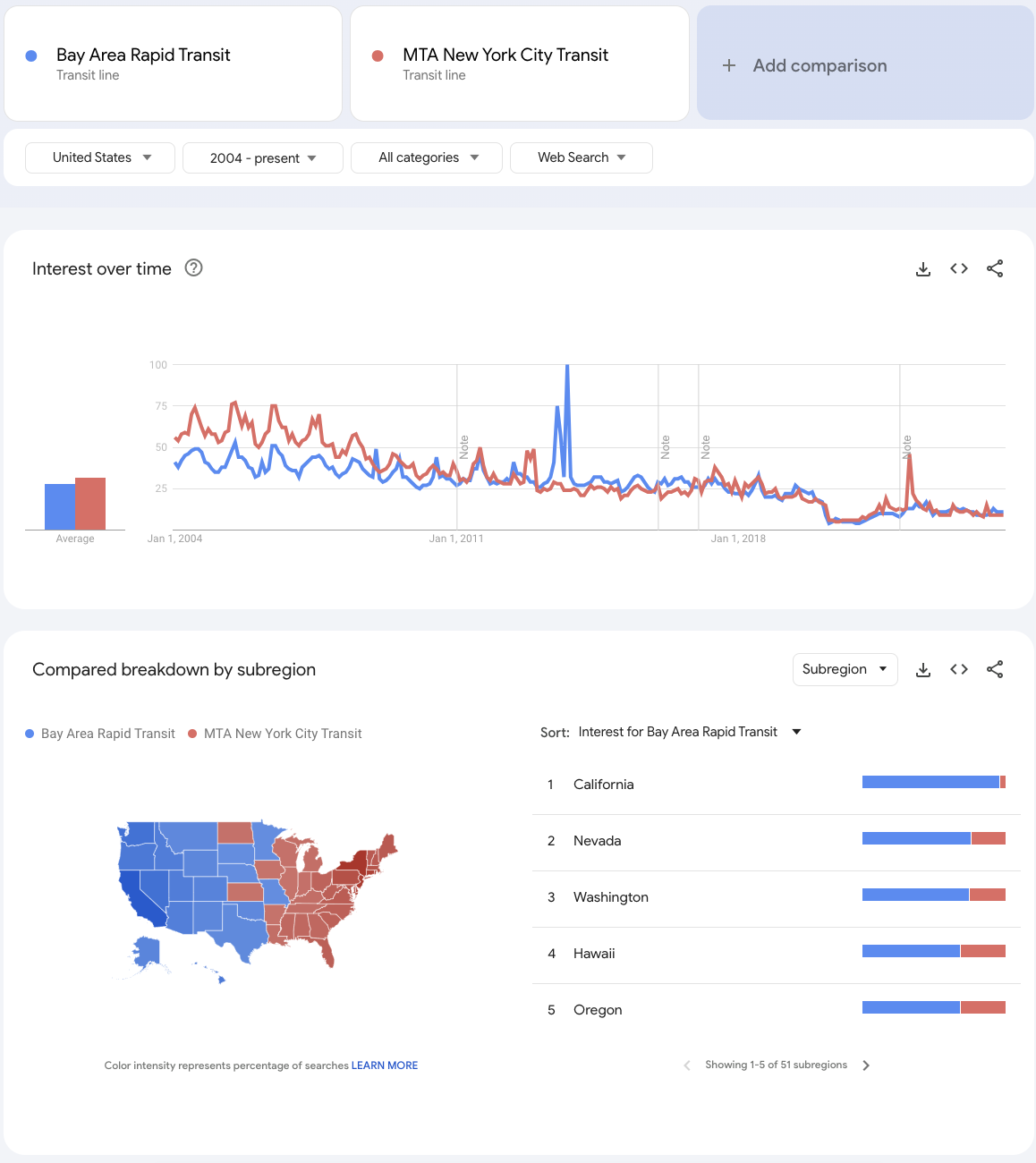

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data from 2004 (the start of availability of the data) to July 2017, when the screenshot was taken.[4]

The image below shows Google Trends data for just one week, with times shown in Pacific Time (the local timezone for BART). Relative interest appears to peak in the evenings, around 5 PM.[5]

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Event type | Details | Associated parts of BART (stations or parts of track) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1872 | Emperor Norton envisages a bridge and an underwater tube connecting San Francisco with the East Bay.[6] The bridge declarations are made in the Pacific Appeal on January 6 and March 23,[7][8] and the underwater tube declaration is made in the Pacific Appeal on June 15.[9] The bridge would be realized as the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, and the underwater tube would be realized as the Transbay Tube, a part of BART. | Transbay Tube | ||

| 1936 | November 12 | Highway transportation | The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge opens for traffic, three years after construction began on July 8, 1933.[10] | Transbay Tube |

| 1945 | Organization | The San Francisco Bay Region Council is created by California's State Reconstruction and Re-Employment Commission.[11]:42 Although funded by the state in its first year, the council incorporates as a private nonprofit organization, and changes its name to the Bay Area Council. Initial supporters of the now private BAC include Bank of America, American Trust Company, Standard Oil of California, Pacific Gas & Electric, U.S. Steel, and Bechtel Corporation. In subsequent years, BAC would be influential in pushing for transportation changes in the San Francisco Bay Area, including enhancements to the bridges as well as the creation of BART. | ||

| 1946 | Acquisition | The Key System Trasit Company, a private operator of electric trollies in the Bay Area, is acquired by National City Lines, a company representing automobile and bus interests, that wishes to eliminate electric trollies from the streets.[11]:45 The removal of a key alternative provider of mass transit would pave the way for mass transit solutions such as BART. | ||

| 1947 | Report | A joint review board by the United States Army and Navy concludes that an additional link is needed between San Francisco and Oakland to reduce congestion on the Bay Bridge. The proposed link is an underwater tube to carry high-speed electric trains.[12][13] | Transbay Tube | |

| 1949 | Legislation | The California state legislature passes the San Francisco Bay Area Metropolitan Rapid Transit District Act.[14] According to the Act, a specially created district would be needed to operate effectively in the context of multiple Bay Area governmental units. The Act provides that the district shall include the city and county of San Francisco and the cities of Alameda, Albany, Berkeley, Emeryville, Hayward, Oakland, Piedmont, and San Leandro, and may include all or any part of Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, San Mateo, and Santa Clara Counties and any city situated therein. In total, over seventy county, city and county, and city governments are potentially involved.[14] | ||

| 1950 | March | Report | The Oakland City Planning Commission submits a preliminary report to the mayors and managers of the cities in the East Bay, with an analysis of and suggested improvements to the Key System local bus service. The report emphasizes the need for a publicly owned rapid transit system on grade-separated rights of way.[14] | |

| 1951 | April | Report | The Senate Interim Committee on the San Francisco Bay Area Metropolitan Rapid Transit Problems issues a report emphasizing the need for a rapid transit system of the kind envisioned by the Rapid Transit Act of 1949, and favors a publicly owned system over a privately owned one.[14] | |

| 1951 | Legislation | The California State Legislature passes a new statute, adding a Section 39 to the Rapid Transit Act of 1949.[14] It creates a 26-member San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission, comprised of representatives from each of the nine counties which touch the Bay. The Commission's charge is to study the Bay Area's long range transportation needs in the context of environmental problems and then recommend the best solution.[14][12][13]:25 Both the joint Army/Navy report[13]:25 and the efforts of BAC are credited for the legislature's decision.[11]:44 | ||

| 1953 | January | Report | A report prepared by the Rapid Transit Commission with the help of the consulting firm Deleuw, Cather & Co. is submitted to the California state legislature. The report is based on plans, data, and information from all the nine counties potentially covered by the Rapid Transit Act. The report argues that highways alone will not solve the transportation problems of the Bay Area, and pushes for mass rapid transit that has a low elapsed time from start to destination, and that can integrate well with other modes of transport.[14] The Senate Interim Committee endorses this report, and draws particular attention to four major interurban operators serving the Bay Area: Pacific Greyhound Lines, Key System Transit Lines, Southern Pacific Company, and Peerless Stages System.[14] | |

| 1953 | November 4 | Legislation | The California state legislature passes another statute, appropriating $400,000 to enable the Rapid Transit Commission to make preliminary studies for the development of a coordinated master plan. The statute provides that the amount appropriated by the state is to be spent only if the nine counties appropriate an additional $350,000. This condition is fulfilled on November 4.[14] | |

| 1953 | November 12 | Report | Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall and Macdonald (PBHM) are commissioned for the study for which $750,000 was appropriated on November 4.[14][11]:52 | |

| 1955 | Report | The Senate Interim Committee on the San Francisco Bay Area Metropolitan Rapid Transit Problems issues a report saying that the general transit situation in the Bay Area has deterioriated. Based on counts of the number of people who commute to work, it concludes that the Bay Area is a single economic unit and is in urgent need of a mass transit system.[14] | ||

| 1955 | Legislation | The California state legislature extends the lifetime of the Rapid Transit Commission (that was created in 1951 and scheduled to end in 1955) to 1957, and allowing any unallocated portion of the previously appropriated $750,000 to be used for publicity of the Bay Area's transit problems.[14] | ||

| 1956 | January | Report | Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall and Macdonald (PBHM) present a report, Regional Rapid Transit (RRT) to the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission, that was commissioned in November 1953. This report is the first planning document for BART and would be the starting point for further reports.[14][11]:52 | |

| 1957 | Highway transportation | A number of citizens' groups protest freeway construction in San Francisco starting around this time, beginning with the Embarcadero Freeway. This leads to increased interest in mass rapid transit as an alternative.[11]:48 | ||

| 1957 | March (legislation), June 4 (creation of the District) | Legislation | Based on the findings of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission, the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BARTD) is formed by the California state legislature, comprising the counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo. Santa Clara county is not included.[12][13]:25 The draft bill had been the subject of public hearings in November 1956, been revised and introduced in January 1957, had another public hearing on February 20, and finally passes when the legislature reconvenes in March.[14] | |

| 1957 | November 14 | Meeting | The first meeting of the Board of Directors of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District occurs.[14] | |

| 1957 | December 16 | Report | The final report of the Rapid Transit Commission is submitted to the California state legislature.[14] | |

| 1958 | Team | Billy Richard Stokes (stylized B. R. Stokes), a former Oakland Tribune newsman, joins the Bay Area Rapid Transit District as its first employee, with the title of Director of information.[15][14] Stokes starts a carefully orchestrated publicity campaign, with the goal of convincing voters to vote favorably for upcoming BART bond measures.[14] | ||

| 1958 | Team | John Pierce, a former executive of the Western Oil and Gas Association (WOGA) becomes the first General Manager of BART.[15][16] | ||

| 1959 | May 14 | Work contracts | BART retains the services of the joint engineering venture composed of Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall and Macdonald, Tudor Engineering, and the Bechtel Corporation to develop a regional plan.[13]:54 | |

| 1959 | Financing plan | A bill is passed in the California state legislature providing for financing of what would later become the Transbay Tube through surplus toll revenues from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.[14] | ||

| 1961 | System plan | A final plan is sent to the boards of supervisors of the five counties. The system would have three endpoints in the East Bay: Concord, Richmond, and Fremont; one in the Northwest at Novato, and one in the South Bay at Palo Alto.[12] | ||

| 1962 | April | County coordination | San Mateo County opts out of BART, citing high costs, existing service provided by Southern Pacific commuter trains, and concerns over shoppers going to San Francisco, hurting local businesses. The withdrawal of San Mateo County leads to Daly City (just at the border between the counties) as the southwest terminus.[12] | |

| 1962 | May | County coordination | Following the withdrawal of San Mateo County, Marin County also withdraws, citing engineering objections and the potential for not getting enough votes. This leads to cancellation of the plans for a northwest terminus and the Geary Subway section of the system.[12] | |

| 1962 | May | Report | The Composite Report (CR) is produced by the consortium of Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall and Macdonald, Tudor Engineering hired by BARTD in 1959.[11]:54 Among the key expectations/predictions of the report are: 1) BART would divert 48,000 workday autos from the streets and highways by 1975, and 2) 258,500 daily passengers would be riding BART in 1975; 157,400 (61%) diverted from automobiles and 39% diverted from existing transit systems.[17] | |

| 1962 | November 6 | County coordination | The remaining three counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Francisco) agree to the modified BART plan with a $792 million bond measure, with terminuses at Richmond, Concord, Fremont, and Daly City.[18][12] The measure, known as Proposition A on the three-county ballot, is able to pass due to two changes engineered by Alan K. Browne of the Bank of America: (a) getting the state legislature to reduce the needed BART vote from 66.67% (the default) to 60%, and (b) allowing for the requirement of crossing the vote threshold to be applied to all votes together, rather than county-by-county. Without both these changes, the measure would not have passed.[11]:59 Supporters of the measure organize a campaign committee called Citizens for Rapid Transit, whose top members are San Francisco bankers.[11]:59 In contrast, there is no organized opposition. Opponents include the Civil League of Improvement and Associations that opposes the taxes needed, the Central Council of Civic Clubs and the San Francisco Labor Council that have more specific objections, and some automobile and older railroad companies, though these companies do not spend resources on opposing the bond measure. | |

| 1962 | November 29 | Work contracts | BART signs a new contract with the successors to the firms it had contracted with to come up with a design for the system. The new contract is for overall system planning through research and development, design, and management of construction. The contract is with the engineering joint venture firm composed of Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade, and Douglas (the successor to Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hall, and MacDonald), Tudor and Bechtel. In short, the joint venture to which the work is contracted is called PBTB.[19][20] | |

| 1962/1963 | Lawsuit | Robert L. Osborne, an Oakland city councilman and East Bay manufacturer, files a lawsuit against BARTD arguing that fixed rail is obsolete, that BART stations would be too far apart to encourage riders, that better and more efficient transit systems were rejected by BARTD, that the ultimate cost would exceed the $792 million approved, that BARTD's contract with PBTB is open-ended and illegal and based on nepotism, and that an illegal, close working relationship exists between the Citizens for Rapid Transit Committee and BART public officials.[14] The court first eliminates some of the allegations, then after hearing the plaintiff's case at trial the court rules against the plaintiff.[14] Many of these allegations would later prove true.[11]:63[14] | ||

| 1963 | Team | B. R. Stokes, who was BART's first employee serving as BART's Director of Information, becomes the General Manager of BART.[15] | ||

| 1964 | June 19 | Construction | BART construction is officially inaugurated by President Lyndon Johnson, presiding over the ground-breaking ceremony for a 4.4-mile test track between Concord and Walnut Creek.[20][14][18] | Concord, Walnut Creek |

| 1965 | October/November | Construction | Construction of the Berkeley Hills Tunnel begins.[20] | Berkeley Hills Tunnel |

| 1966 | January 24 | Construction | Construction of the Oakland subway part of BART, including the Oakland Wye (the part of BART in Oakland that is underground), begins.[18][20] | Oakland Wye; stations of 19th Street, 12th Street, Lake Merritt |

| 1966 | August | PBTB issues its specification for the work required to design and provide the automatic train control (ATC) system.[21]:123 | ||

| 1966 | October | Construction, Referendum | Since 1965, the government of the city of Berkeley had been pressing BART to construct the Berkeley portion of the BART underground (instead of elevated), and said it is willing to pay the additional construction costs. The city government is concerned that an elevated track would reduce connectivity between the black population of South Berkeley and the rest of the city, and reduce prices in the area. Due to disputes between Berkeley city engineers and BART engineers about the magnitude of additional costs, competitive bidding is opened up both for underground and elevated construction, and the city of Berkeley decides, after seeing the difference between the bids, to pay extra for underground construction. A referendum is held in October 1966, where the residents of Berkeley overwhelmingly vote in favor of underground construction and the corresponding tax increase (with 83% in favor, compared to the 75% that city officials were hoping for).[14] BART's website claims that this led to a 2.5-year delay in construction, $18 million in additional costs, and a 17-month delay in starting Ashby station construction.[20] | Ashby, Berkeley, North Berkeley (stations in Berkeley) |

| 1966 | November | Construction | Construction on the Transbay Tube begins, as the first of 57 giant steel and concrete sections of the 3.8-mile tube is lowered to the bottom of the Bay by a small navy of construction barges and boats.[20] | Transbay Tube |

| 1967 | Report | In response to criticism by the California Society of Professional Engineers (CSPE), the National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) Board of Ethical Review reviews the case. The Opinions are published as Case No. 66-1 in Vol. 2, 1967. The Opinion concludes that it is not appropriate to issue criticism of the fee arrangements in the manner that CSPE did.[13]:97 | ||

| 1967 | February | Construction | The boring of the Berkeley Hills Tunnel is completed.[20] | Berkeley Hills Tunnel |

| 1967 | May | Work contracts | The contract for the operation of BART's automatic train control (ATC) system is won by Westinghouse for $26.1 million, as it is the lowest bidder, $3 million below the second lowest bidder. The other bidders for the contract are General Railway Signal Company, Philco-Ford Company, General Electric Company, and Westinghouse Air Brake Company.[20][19] | |

| 1967 | July 25 | Construction | Construction for BART tracks along the Market Street Subway in San Francisco commences. The construction is carried out using cut-and-cover.[22][18] | Market Street Subway; stations include downtown San Francisco stations of Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell Street, and Civic Center |

| 1968 | Work contracts | IBM wins a $5 million contract to design BART's fare ticket collection machines.[23] | ||

| 1969 | April 3 | Construction | The final section of the Transbay Tube is laid out (it has not yet been fitted for use by trains).[24] | Transbay Tube |

| 1969 | April | Legislation | After three years of debate, the California state legislature approves BARTD's request for $150 million in funds, by levying a 0.5% sales tax in the BART counties.[20][15] | |

| 1969 | July | Train cars | The contract for making BART's electric train cars is won by Rohr Industries, Inc. of Chula Vista, California. The initial contract is for 250 train cars, at a cost of $80 million.[20][23] | |

| 1969 | August | Construction | The Transbay Tube construction is completed.[18] | Transbay Tube |

| 1969 | September 1 | Controversy | At the Contra Costa County meeting to nominate candidates for the BART Board, Roy Andersen, the candidate of the Diablo Chapter of the CSPE delivers a speech critical of the BART/PBTB relationship.[13]:101 | |

| 1969 | November 9 | Preview | A section of the Transbay Tube is opened for pedestrian traffic, prior to being fitted out for train use.[25] | Transbay Tube |

| 1970 | August | Train cars | The first prototype BART train car is delivered by Rohr Industries, Inc.[23] | |

| 1970 | Legislation | The California state legislature creates the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC).[26] The MTC works closely with the California Department of Transportation and is the public governmental agency responsible for planning, financing, and coordinating transportation for the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area; BART falls under its purview.[27] The nine counties include the three BART counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Francisco) and six others (Marin, Napa, San Mateo (that is touched by BART but is not a BART county), Santa Calara, Solano, and Sonoma).[28] The Commission would hold its first meeting in February 1971.[26][29] | ||

| 1971 | early year | Train cars, system testing | The ten test prototype train cars delivered so far are being operated round-the-clock around the Fremont line, to prove out the new design before full-scale production.[23] | |

| 1971 | January 27 | Construction | Construction of the two-level Market Street Subway is completed, with a final tunnel bore holed through Montgomery Street Station.[20] | Market Street Subway; stations include downtown San Francisco stations of Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell Street, and Civic Center |

| 1971 | September | Report | The Battelle Memorial Institute publishes a report on BART, pointing out that the automatic train control (ATC) system would suffer from a train detection problem.[21]:136 | |

| 1971 | October | Fare collection | IBM demonstrates the first group of prototype fare collection machines to the BARTD Board of Directors. The machines are manufactured at IBM's San Jose plant.[23] | |

| 1971 | November 5 | Train cars | The first production car for revenue service is delivered.[18] Note that SFGate reports the date as June 27, 1965, but this seems incorrect based on the rest of the timeline.[22] | |

| 1971 | December | The BART District Board adopts the official inter-station fare schedule, ranging from a 30 cent minimum to a $1.25 maximum fare.[23] | ||

| 1971 | December | System testing | During system testing, BART has a collision between a moving train and a stationary train. Despite concerns from the board of directors, BART management dismisses the problem as not serious.[21]:135 | |

| 1972 | January | The BART District Board approves 75% fare discounts for patrons above 65 years for patrons over 65 and patrons under 13, with discount tickets to be sold through local bank branches instead of at BART stations.[23] | ||

| 1972 | January | System testing | BART begins total acceptance testing of its entire system. Max Blankenzee, one of the three engineers who would be fired from BART in March, argues against starting total acceptance testing when the subsystems have not been fully tested.[21]:129 | |

| 1972 | February and March | Controversy | Three engineers working for BART, Max Blankenzee, Robert Bruder, and Holger Hjortsvang, had identified safety problems with the Automated Train Control (ATC).[21] They contact Daniel Helix, mayor of Concord and a member of the BART board of directors, who raises the matter with the board, and goes public with the issues on Febrary 7-9. On February 24 or 25, at a public meeting of BART, the issues are raised. The board votes ten to two in support of BART management.[19][21]:118 On March 3, BART, having determined the identities of the three whistleblowing engineers, gives them the option of resigning or being fired. After they refuse to resign, they are all fired.[19] | |

| 1972 | September 11 | Service start | BART opens service. Initial service is between the stations of MacArthur and Fremont (completely in the East Bay). Iinitial service is on weekdays only, and comprises eight trains, each of which is two or three cars long.[22][18][23] | MacArthur, 19th Street, 12th Street, Lake Merritt, Fruitvale, Coliseum, San Leandro, Bay Fair, Hayward, South Hayward, Union City, and Fremont |

| 1972 | September 27 | Federal funding | United States President Richard Nixon issues a statement that an additional $38.1 million of federal funds will be available to BART from the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (now the Federal Transit Administration), based on provisions of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1970. The funds will help go toward making the remaining 47 miles of BART track operational. Through 1972, federal funds for BART have totaled $181 million, or 13% of the total cost.[30] | |

| 1972 | Report | BART conducts studies of the feasibility of the following extensions: Daly City to San Francisco International Airport, Coliseum to Oakland International Airport, Concord to the Pittsburg-Antioch area, and Bay Fair (on the Fremont line) to the Livermore-Pleasanton area.[23] | Daly City, Colma, South San Francisco, San Bruno, San Francisco International Airport, Oakland International Airport, North Concord/Martinez, Pittsburg/Bay Point, Castro Valley, West Dublin/Pleasanton, Dublin/Pleasanton (and other stations still being considered) | |

| 1972 (continuing till 1974) | Controversy, Safety | Concerned by the controversy surrounding the engineers who raised safety concerns with BART, California's legislative analyst A. Alan Post commissions Bill Wattenburg to review problems with BART. Wattenburg identifies a number of potential flaws with the method BART uses to track trains, and provides suggestions to improve the system, albeit in a combative fashion that generates a lot of publicity (including San Francisco Chronicle coverage) but is not well-received by BART.[31][32] Wattenburg continues highlighting the flaws and potential solutions till as late as 1974.[33] | ||

| 1972 | October 2 | Accident | A failure of the Automated Train Control (ATC) system at BART causes an accident at Fremont station called the Fremont flyer, where a train runs off the end of the elevated track and crashes to the ground at the parking lot. Four people are injured.[34][35] | |

| 1972 | November | Report | At the request of the California Senate Public Utilities and Corporations Committee, California's legslative analyst A. Alan Post issues a report containing criticisms of BART's Automated Train Control (ATC) system as well as its contracting and operating procedures. Within three weeks, BART issues a 157-page response, agreeing to some of the suggestions (and outlining its intention to implement them) but viewing others as nitpicky, questionable, and misguided.[13]:233-235[36][34] | |

| 1972 | December | Controversy | IEEE Spectrum publishes a letter from Hjortsvang (one of the BART engineers who had been fired for his criticism of BART's safety) (Forum, pp. 16–17). In the letter, he outlines criticisms of both BART and the Westinghouse-designed ATC system.[21]:122 | |

| 1972 | Commission | The BART Impact Program, a policy-oriented study and evaluation of the impacts of BART, is started, with funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the California Department of Transportation, and administed by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) under contract. The program would run till 1978 and produce its final report in 1979.[37][29] | ||

| 1973 | January 29 | New stations | BART opens service from MacArthur to Richmond (in the East Bay), as well as all the stations along the line (except MacArthur which was already open).[18] | Ashby, Berkeley, North Berkeley, El Cerrito Plaza, El Cerrito Del Norte, and Richmond. |

| 1973 | January 31 | Report | A report is produced by a special blue ribbon panel of experts, namely Drs. Bernard Oliver, Clarence Lovell, and William Brobeck, commissioned by the Senate Public Utilities and Corporations Committee, working closely with BART. The report includes 21 technical recommendations.[13]:233-235[21]:122 The views of the experts are summarized in "A prescription for BART" in IEEE Spectrum, pp. 40–44, April 1973.[21]:122 | |

| 1973 | May 21 | New stations | BART opens service from MacArthur to Concord (in the East Bay), as well as all stations on the line (excluding MacArthur that was already in service) completing the East Bay part of its initial plan.[18] | Rockridge, Orinda, Lafayette, Walnut Creek, Pleasant Hill, and Concord. |

| 1973 | August | Report | A 42-page report by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), titled Safety Methodology in Rapid Rail Transit System Development (NTSB-RSS-73-1), is published.[38] The report is in response to concerns raised around transit system safety, partly due to safety concerns at BART.[39] | |

| 1973 | August 10 | Preview | The first test run of a train under automatic control from West Oakland to Montgomery is performed. The train runs at full speed, taking seven minutes and returning in another six minutes.[40] | Transbay Tube, stations of West Oakland, Montgomery |

| 1973 | November 3, 5 | New stations | BART opens its service in San Francisco (not yet connected with the East Bay), from Montgomery to Daly City.[18] | Montgomery, Powell Street Station, Civil Center/UN Plaza, 16th Street/Mission, 24th Street/Mission, Glen Park, Balboa Park, and Daly City. |

| 1973 | November | Automatic train control | Hewlett-Packard (HP) demonstrates to BART a model of a logical prediction system for better tracking of the position of trains in the BART system. Convinced by this, BART instructs Westinghouse to incorporate the measure in its control system. Hjortsvang, one of the engineers previously fired from BART, would later note that HP's design is based on the suggestion he had previously made to BART to improve the reliability of train tracking.[21]:125 | |

| 1974 | May 24 | Team | BART general manager B. R. Stokes steps down from his role, after legislators make his resignation a precondition for continued funding of BART.[41][15] | |

| 1974 | August 27 | Approval | The California Public Utilities Commission gives BART permission to start transbay service for two lines: Fremont to Daly City and Concord to Daly City. The trains would operate under a computer-augmented block system (CABS-l) with one-station separation between trains.[21]:122 | |

| 1974 | September 16 | New stations | BART opens its station in West Oakland and begins trans-bay service between its East Bay and San Francisco stations.[18] Initially, only the Concord and Fremont trains go across the Bay to San Francisco; passengers on the Richmond line need to transfer at MacArthur or 12th Street. As of this time, headways for trains are 12 minutes.[37][21]:122 | West Oakland, system-wide |

| 1974 | October | Vehicles and devices on BART | BART temporarily authorizes bicycles on BART, with folding bikes allowed at all times and standard-size bikes allowed outside of rush hours. There is a limit of 5 bicycles per train, all bicycles must be in the rear of the last car, and anybody using a bicycle needs to have a permit (permits are issued for 3-year periods). The policies would become permanent in December 1975.[42]:1-1 | |

| 1974 | November 5 | Team | A nine-member elected Board of Directors replaces the previous appointed Board.[18] The leadership of BART changes considerably, as voters are dissatisfied with the previous board members. | |

| 1975 | July 30 | Train cars | Rohr Industries, Inc. completes the delivery of the 450 train cars it was contracted to make for BART (the original contract for 250 cars for $80 million was entered into in July 1969, and an additional 200 cars were contracted later, for another $80 million). 64% of the $160 million base cost is funded through federal transit funds.[23] | |

| 1975 | May 26 | Legislation | The California Senate amends the California Public Utilities Code by adding (or updating?) Section 29047. The new Section 29047 says that the Bay Area Rapid Transit District is subject to regulations of the California Public Utilities Commission, and must reimburse the California Public Utilities Commission for the cost of regulating it.[43][39] | |

| 1975 | July 1 | Fares | BART adopts a 75% fare discount for people with disabilities, and increases the discount for seniors from 75% to 90%.[18] | |

| 1976 | January 1 | Service hours/frequency/capacity | Permanent night service goes into effect. Hours of operations are extended to 6 AM to midnight (only weekdays).[18] This is after night service was introduced on a temporary basis in November 1975.[37] Previously, the hours of service were 6 AM to 8 PM.[37] | |

| 1976 | May | Report | The Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) produces a report on the use of automatic train control (ATC) in rail rapid transit. BART is one of the five rapid transit systems studied. The only other transit system that uses ATC extensively at the time is the PATCO Lindelwold line, which is also studied. The other transit systems included in the study are those of Chicago New York City, and Boston.[39] | |

| 1976 | May 27 | New stations | BART opens its Embarcadero station, its first infill station. This would become BART's busiest station.[18] | Embarcadero |

| 1976 | July 1 | Transit connections | SamTrans (the San Mateo Country Transit District) is incorporated. This provides bus service in San Mateo County, and in particular, provides bus feeder lines into the Daly City BART station. | Daly City |

| 1976 | October | Report | A monograph titled The BART Experience -- What Have We Learned? by Melvin M. Webber, and supported jointly by the Institute of Transportation Studies and the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley, is published.[17] The report includes: design considerations, patronage, effect on highway traffic, effect on metropolitan development, and various aspects of the finances. Findings from the report would be echoed in later reports.[37] The report argues that BART failed to meet its patronage projections by a huge margin, part of which is due to BART having lower capacity (shorter train cars, fewer hours of service, low service frequency) and poorer service reliability compared to expectations. In terms of ridership, the report finds that BART primarily displaces transbay bus transit, compared to which BART is faster but more expensive (both in direct fare terms and in terms of subsidies). BART does not displace local, short-trip, transit. BART's effect on reducing highway congestion is lower than expected, and the report attributes this to BART being slower and less convenient than automobiles, and not clearly cheaper. Only 35% of BART riders report that they would have used an automobile instead of BART, compared to the prediction of 61% in the 1962 Composite Report. Key reasons people use BART include not owning a vehicle and wanting to avoid the higher stress of a driving commute. Initial reductions in highway traffic after the opening of BART routes (the Berkeley Hills Tunnel, the Transbay Tube, and BART lines that parallel freeways) did not last long, with rapid recovery to original levels. | |

| 1976 | December 6 | Service hours/frequency/capacity | BART increases commute-hour length on all trains, going up to ten-car trains, with a seating capacity of 720.[18] | |

| 1977 | November | Service hours/frequency/capacity | BART begins Saturday service (6 AM to midnight).[37] | |

| 1978 | June 30 | Economics | BART's farebox recovery ratio is reported at 35%, with an average of $0.73 collected in fares and $2.02 spent per passenger. In total, revenue from fares is $28 million and operating cost is $78 million. The shortfall is met through a portion of sales tax and property tax in the three counties where BART is operational.[37] | |

| 1978 | July | Service hours/frequency/capacity | BART begins Sunday service (9 AM to midnight), thus making it available all days of the week.[37] | |

| 1978 | November 3 | Report | The report BART's first five years : transportation and travel impacts : interpretive summary of the final report is published. This is part of the BART Impact Program, sponsored by the Department of Transportation and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[37] This echoes many of the findings of the October 1976 Webber monograph, while also mentioning recent service capacity enhancements and more up-to-date financials.[17] | |

| 1978 | Transit connections | The Amtrak-operated San Joaquin train, that runs between Bakersfield (near Los Angeles) and Oakland, starts stopping at Richmond station, a station shared with (and a terminus for) BART. Previously, the route, that runs on old Southern Pacific Railroad tracks, passed through but did not stop at Richmond. The route started operating under Amtrak on March 5, 1974.[44] | Richmond | |

| 1979 | January 17 | Accident | The fifth and sixth cars of a seven-car westbound BART train (Train No. 117) catch fire at 6:06 p.m. while in the Transbay Tube. Forty passengers and two BART employees are evacuated from the burning train through emergency doors into a gallery walkway located betwen the two tracks, and then into a train on the tracks running the other direction. One fireman dies when the gallery suddenly fills with black toxic smoke. 24 firemen, 17 passengers, 3 emergency personnel, and 12 BART employees are treated for smoke inhalation. Total property damage is estimated at $2,450,000. An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determines the probable cause of the accident to be the breaking of collector shoe assemblies on the train when it struck a line switchbox cover which had fallen from an earlier train. NTSB also finds the failure of BART to conform to the emergency plan, and to coordinate rescue efforts between the San Francisco and Oakland fire departments, to be contributing factors to the severity of the incident.[45] | Transbay Tube |

| 1979 | June, September | Report | The BART Impact Program produces its final report. The report is submitted in June and published in September.[29] | |

| 1980 | February 18 | Transit connections | The San Francisco Muni Metro begins operation, with the N line.[46]:250[47] The Muni Metro (and the N line in particular) shares the four downtown San Francisco stations of Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell, and Civic Center, the four stations that are part of the Market Street Subway. The Market Street Subway and the four stations in it were originally built in a double-deck configuration, with the lower deck used for BART and the upper deck used for Muni Metro -- the start of Metro service puts the upper deck in operation. | Market Street Subway; four stations Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell, Civic Center |

| 1985 | Construction | Construction for the Daly City BART Turnback Improvement Project commences.[48]:18 | Daly City, also affecting later construction leading to Colma | |

| 1985 | Report | The Daly City Intermodal Study proposes a $14 million of access, circulation and parking improvements to the Daly City BART station, including the construction of a park-and-ride lot south of the Daly City BART with a connecting bus service.[48]:18 The improvements would be completed in 1989. | Daly City | |

| 1986 | July 30 | Safety, Train cars | BART completes a fire-hardening program on all its transit vehicles, and claims that with the completion of the program, it has the most fire-safe transit vehicles in the United States.[18] | |

| 1987 | Train cars | Alstom begins construction of C1 cars, a new type of train car, for BART. C1 cars, unlike the existing A and B cars, can be used both as middle cars and as end cars, allowing for more rapid resizing of train length.[49] For more, see Bay Area Rapid Transit rolling stock#C series. | ||

| 1988 | Train cars | The C1 cars constructed by Alstom begin to enter service.[50] | ||

| 1989 | Train cars | The construction of C1 train cars by Alstom is completed.[49] For more, see Bay Area Rapid Transit rolling stock#C series. | ||

| 1989 | Construction | The improvements proposed in the 1985 Daly City Intermodal Study, including improvements to access, circulation, and parking, pedestrian access, and new park-and-ride facilities, are completed.[48]:19 | ||

| 1989 | October 17 | Highway transportation shutdown | The Loma Prieta earthquake causes severe damage to the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge,[51] causing it to close for a month (it reopens on November 17 or 18, 1989).[52] During the time of its closure, BART ridership soars as Bay Bridge commuters turn to BART, with ridership reaching a record high of 357,135 on November 16, just before the Bay Bridge reopens.[18] | Transbay Tube, effect on transbay travel |

| 1990 | December 12 | Report | The Final Environmental Impact Statement/Final Environmental Impact Report (FEIS/FEIR) for the construction of Colma station, BART's first extension south of its current southwest terminus of Daly City, is published. The report is prepared by the Urban Mass Transportation Administration working along with BART and San Mateo County, and is pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act, the Urban Mass Transportation Acts, and the California Environmental Quality Act. The report compares Colma stations to alternatives including no build, transportation systems management (TSM), a Colma BART station extension just south of Daly City, and the main Colma station proposal, dubbed the locally preferred alternative. The report comes out in favor of building Colma station. A draft version (DEIS/DEIR) was published in October 1988 to solicit comments, and a formal public hearing was held on December 8, 1988.[48] | Colma |

| 1991 | October 25 | Construction | The first phase of a $2.6 billion extension program begins with simultaneous groundbreaking ceremonies for the Dublin/Pleasanton and West Pittsburg extensions.[18] | Future stations: Castro Valley, West Dublin/Pleasanton, Dublin/Pleasanton, North Concord/Martinez, Pittsburg/Bay Point |

| 1991 | December 12 | Transit connections | Amtrak launches a new route, the Capitol Corridor, with initial name Capitols. The route runs from San Jose to Sacramento, respectively the former and current capital of California. The train stops at Richmond, where passengers can transfer between Amtrak and BART. The part of the route south of Richmond runs along Amtrak tracks that are roughly parallel to and 1–2 miles west of the BART route from Richmond to Fremont.[53] | Richmond |

| 1993 | Fare collection | BART announces a project with County Connection, a bus service in the Concord area, to introduce Translink, a single fare card that can be operated across the two systems.[54] | ||

| 1994 | Train cars | C2 train cars constructed for BART by Morrison-Knudsen enter service. Like the C1 cars constructed by Alstom, these train cars have the flexibility of being used both as middle and end cars, allowing for rapid train resizing.[50] | ||

| 1994 | April | Team | Richard A. White becomes General Manager of BART after Frank Wilson leaves the position to become Secretary of Transportation for the state of New Jersey.[55] | |

| 1994 | July to September | Labor dispute | BART union members threaten to strike, but the strike is prevented through a 30-day cooling-off period in July. Prolonged negotiations between management and unions lead to an agreement in late September.[56] The handling of the negotiations by SEIU Local 790 director Paul Varacalli would be met with mixed responses from BART workers, with some praise for him getting a good deal for workers, and some criticism for major givebacks to BART management.[57] | |

| 1994 | August 31 | Train cars | The first of a new generation of transit cars arrives at the Hayward maintenance facility. The transit car is part of an 80-car order.[18] | |

| 1995 | Train cars | BART contracts with ADTranz, a subsidiary of Mercedes Benz (and later acquierd by Bombardier Corporation) to replace the brown seats in train cars with polyurethane cusioning.[58] | ||

| 1995 | November 15 | Fare collection | BART and County Connection abandon Translink, their smart fare collection program, due to high costs.[54] | |

| 1995 | December 16 | New stations | The North Concord/Martinez station opens up for revenue service. This is the first of two stations to open on the West Pittsburg part extension, and replaces Concord as the terminus for its line. | North Concord/Martinez, indirect effect on Concord (which is now no longer the terminus) |

| 1996 | February 24 | New stations | The Colma station opens for revenue service, with a colocated SamTrans Transit Center. Not all trains coming to San Francisco go all the way to Colma; some of them still stop at Daly City. Balboa Park is the official southbound transfer station and Daly City is the official northbound transfer station for people who want to go to Colma from lines that do not extend all the way to Colma. Residents express concerns about high cost of financing the extension, limited usefulness to them, and displacing Caltrain.[59][18] | Colma (also indirect effect on Daly City and Balboa Park) |

| 1996 | October | Vehicles and devices on BART | A 6-month trial period is initiated where the requirement for a permit to have a bicycle on BART is removed, and bikes are now allowed in the rear of any car other than the first car (previously, they were only allowed in the rear of the last car). The trial period is successful and the policies become permanent in March 1997.[42]:1-1 | |

| 1996 | Data | The first BART Customer Satisfaction Survey is conducted. The survey would be conducted every two years since that time, until at least 2016.[60] | ||

| 1996 | September 30 | Team | Thomas Margro becomes General Manager of the BART District, succeeding Richard A. White who left for the top job at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.[61] | |

| 1996 | December 7 | New stations | BART opens the Pittsburg/Bay Point station for revenue service, four months ahead of schedule. This replaces North Concord/Martinez as the terminus for its line.[18] | Pittsburg/Bay Point; indirect effect on North Concord/Martinez |

| 1997 | May 10 | New stations | The Dublin/Pleasanton line opens for revenue service. The two new stations that open are Castro Valley station and Dublin/Pleasanton (also known as East Dublin/Pleasanton); the latter is the terminus of the line.[18] A third station, West Dublin/Pleasanton, that is in between the other two, would open later. | Castro Valley, Dublin/Pleasanton |

| 1998 | January 15 | Fare collection | A report by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission estimates full availability of Translink (a smart card that can work across Bay Area transit agencies) by 2001.[62] | |

| 1998 | Data | BART conducts a Station Profile Study, to understand the profile of riders at each of its stations.[63] | ||

| 1998 | Work contracts | CBS Outdoor wins the exclusive right to manage advertisements on BART stations and trains.[64] | ||

| 1999 | April | Vehicles and devices on BART | Bicyclists are no longer required to use the rear of the car; they can use either door of any car other than the first car.[42]:1-1 | |

| 2001 | January | Data | BART's website reports ridership numbers for every pair of entry and exit station from this time onward.[65] | |

| 2001 | September | Station facilities | BART closes restrooms at all stations following a recommendation from the Department of Homeland Security in the wake of the September 11 attacks. Soon, all but the underground restrooms (ten stations total) would be reopened. Discussions on reopening the underground stations, with a more "secure" remodeled layout would continue till 2017.[66][67][68] | |

| 2001 | Connectivity (cellular) | The BART Board authorizes staff to develop a privately financed underground wireless telecommunications system to provide cell phone use and Internet access for the entire BART system.[69] In response to people concerned about others using cellphones and distracting others during the commute, BART condicts a pair of polls. The September 11 attacks, where cellphones are highlighted as having been useful in dealing with the situation, are believed to be a factor that makes people more in favor of improving cellular connectivity on BART.[70] | ||

| 2002 | Fare collection | Translink, the smart card payment system, launches.[71] | ||

| 2002 | Vehicles and devices on BART | BART creates its first Bicycle Access and Parking Plan.[42] | ||

| 2003 | June 22 | New stations, transit connections | BART extends its service south of Colma, simultaneously opening stations in South San Francisco, San Bruno, San Francisco International Airport, and Millbrae.[18] The Millbrae station is an intermodal terminal connecting with Caltrain; Caltrain had moved its own Millbrae station to this location in Spring 2003. | South San Francisco, San Bruno, San Francisco International Airport, Millbrae |

| 2004 | January 1 | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. The minimum fare is now $1.25 and the excursion fare is now $4.40.[72][73] | |

| 2004 | May | Connectivity (cellular) | BART works with cellphone carriers Sprint, Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile to provide cellular access in its underground stations in downtown San Francisco.[69] | Downtown San Francisco stations (Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell Street, Civic Center) |

| 2004 | August 23 | Recognition | The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) identifies BART as the #1 transit system in the United States among systems with 30 million or more annual passenger trips.[18][61]ref name=bart-margro-retires>"BART General Manager announces resignation". Bay Area Rapid Transit. April 10, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2017.</ref>[74] | |

| 2004 | November 2 | Safety, referendum | Bay Area voters approve Measure AA in a referendum. The measure allocates $980 million from property taxes for the BART Earthquake Safety Program, including seismic retrofitting of the Transbay Tube and elevated tracks to better withstand an earthquake.[18][75][76][77] | |

| 2004 | Information for riders | BART launches www.bart.gov/wireless for phones. This is before the smartphone era, and this website is optimized for the traditional phones of its era. The site would continue to be available even after BART launches its mobile site at m.bart.gov in 2011, but it is no longer available as of 2019.[78] | ||

| 2005 | October 15 | Highway transportation shutdown | Caltrans shuts down all eastbound lanes on the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge over the weekend for earthquake retrofit work, increasing the pressure on BART to carry transbay traffic. BRT runs transbay trains around the clock to serve transbay travelers.[79][18] | Transbay Tube |

| 2005 | Connectivity (cellular) | BART expands cell service to the non-downtown San Francisco underground stations, and later to the entire underground line in San Francisco.[69][70] | 16th Street/Mission, 24th Street/Mission, Glen Park, Balboa Park | |

| 2006 | January 1 (announcement: December 2, 2005) | Fares | New BART fares are effective from this date. The inflation-based fare increase is 3.7%, and there is an additional 10-cent capital surcharge to trips made within Alameda, Contra Costa and San Francisco Counties, including Daly City. The minimum BART fare is now $1.40 (up from $1.25).[73] | |

| 2006 | March 27, 28, and 29 | Service disruption | BART has to shut down service for several hours on each of Monday March 27, Tuesday March 28, and Wednesday March 29, due to computer shutdowns. The firs two incidents are due to a problem with the latest version of software that was installed. The third instance is an unexpected side-effect of the work to configure a backup system for faster recovery in such incidents. In an article on April 5 on its website, BART offers a postmortem and plans for improving in the future.[80] | |

| 2006 | June 3 | Highway transportation shutdown | Caltrans shuts down the lower deck of the Bay Bridge for earthquake retofit work for the weekend. BART runs 24-hour service for selected stations for the weekend to help people travel across the Bay during that time period.[81] | Transbay Tube |

| 2007 | April 29 | Highway transportation shutdown | A fire in a gasoline tanker destroys part of the MacArthur Maze, closing two freeways feeding into the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. BART increases the frequency of transbay service and announces free transit and runs longer trains on Monday, April 30.[18][82] | Transbay Tube, systemwide effects |

| 2007 | August 23 | Team | The BART Board of Directors votes 6-3 to appoint Dorothy Dugger, the current Interim General Manager, as General Manager. Dugger would become BART's first female General Manager, and would take the job after serving BART since September 1992 and being Deputy General Manager since April 6, 1994. She succeeds Thomas Margro, who retired in June.[83][84] | |

| 2007 | September 1, 2, 3 | Highway transportation shutdown | BART runs hourly, overnight service to 14 stations Saturday, September 1, Sunday, September 2 and Labor Day, Monday, September 3 when Caltrans closes the Bay Bridge for earthquake retrofit work.[85] | Transbay Tube |

| 2008 | January 1 | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. The minimum fare is now $1.50 (up from $1.25) and the excursion fare is now $4.90.[86][87] | |

| 2008 | July 21 | Connectivity (cellular) | BART works with cellphone carrier MetroPCS to add MetroPCS to the list of carriers (previous list: Sprint, Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile) with service in the underground San Francisco portion of its line.[88] | All of the underground San Francisco system (stations: Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell Street, Civic Center, 16th Street/Mission, 24th Street/Mission, Glen Park, Balboa Park) |

| 2008 | July, August | Information for riders | BART gets a Twitter account (@SFBART) in July. The earliest surviving tweet is from August 13.[89] Over the years, BART would use its Twitter account to complement its other means of providing news and real-time updates to riders, reaching over 30,000 tweets by early 2019. | |

| 2008 | August 19 | Vehicles and devices on BART | BART approves a pilot program for the use of Segways and other Electric Personal Assistive Mobility Devices (EPAMD) on the BART system.[90] | |

| 2008 | October 1 | Work contracts | Titan wins the exclusive right to manage advertisements on BART stations and trains (October 1 is the effective date, the winning of the contract is announced in March 2008), replacing CBS Outdoor, which has held the contract since 1998.[64][91] The company would later merge with Control Group to form Intersection Media.[92][93] | |

| 2008 | Data | BART conducts a Station Profile Study, to understand the profile of riders at each of its stations. This updates data previously collected in 1998.[63] | ||

| 2009 | January 1 | Violence | Oscar Grant is shot at Fruitvale station by BART police officer Johannes Mehserle, who restrained him after responding to reports of fights on a crowded BART train from San Francisco.[94][95][96][97][98] | Fruitvale |

| 2009 | February 2 | Connectivity (Internet) | BART enters into a 20-year agreement with WiFi Rail Inc., a company based on Sacramento, to provide high-speed wifi service along the BART system, after completing an initial testing phase. Phase 2 (the post-testing phase) would be planned to extend service through San Francisco and Oakland and through the Transbay Tube.[99] | |

| 2009 | July 1 (announcement: June 30) | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. This is an inflation-based fare increase of 6.1% (average 20 cents) and is one of a series of fare increases from 2006 to 2012 that were approved by the BART Board in May 2003. The minimum fare is now $1.75 (up from $1.50) and the excursion fare is now $5.20 (up from $4.90).[100][101] | |

| 2009 | September 22 | Information for riders | BART announces beta testing of on-demand SMS for riders, where they can send a SMS to a BART number and get back information such as train arrivals, delay advisories, elevator status.[102] | |

| 2009 | September 30 | Construction | Construction begins on BART's Warm Springs Extension, extending BART from its current southeastern terminus of Fremont to a new station in Warm Springs/South Fremont.[18] | Fremont, Warm Springs/South Fremont |

| 2009 | October 2 | Information for riders | BART annoucnes that real-time arrival information is now available over Interactive Voice Response (IVR) through local telephone numbers for the six regions that BART serves.[103] | |

| 2009 | October 28 | Highway transportation shutdown | An emergency shutdown of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge leads to record increases in BART ridership. Ridership further increases as BART runs longer and overnight service to meet transbay travel demand.[18] | Transbay Tube |

| 2009 | December 21 | Connectivity (cellular) | BART expands cellphone coverage to the Transbay Tube, with carriers AT&T, T-Mobile, Verizon, and Sprint. The costs are shouldered by the carriers. The additional service expansion completes 35% of the tunnels and eight of the 16 underground stations.[69][104] | Transbay Tube |

| 2009 | December 30 (announcement: August 16) | Team | On August 16, 2009, Gary Gee, BART Police Chief, announces his retirement in the wake of criticism of his leadership after the Oscar Grant shooting. His last day of service would be December 30.[105][106] | |

| 2010 | January 25 | Information for riders | BART announces the official launch of its API (application programming interface) which allows developers to programmatically access a bunch of information about the BART system including real-time information about train schedules. There is also an associated online discussion group using Google Groups.[107] | |

| 2010 | March 30 | Service disruption | A fire between Powell Street and Civic Center during morning rush hour results in delays for many commuters. BART calculates a delay of 15 to 30 minutes, but many commuters experience longer delays. BART apologizes for the disruption and for underestimating delays.[108] | Powell Street, Civic Center, systemwide effects |

| 2010 | June 1 | Team | Kenton Rainey, who previously served as the Fairfield Police Chief, becomes the new Chief of BART Police.[98][109] He would contine to serve till his retirement on December 31, 2016.[110] Rainey would subsequently go on to become police chief of the University of Chicago Police Department.[111] | |

| 2010 | June 16 | Fare collection | Translink, the smart card payment system used in BART and other Bay Area transit agencies, is renamed Clipper and launches officially at full scale.[71][112][113][114][115] | |

| 2010 | July 15 | Legislation | California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signs the BART Public Safety Accountability Act into law, giving citizens a role in directing policy and reviewing practice in the BART police force for the first time, in response to problems highlighted by the shooting of Oscar Grant.[116][117] The Act modifies the California Public Utilities Code to include authorization for the BART Board of Directors to establish the Office of Independent Police Auditor (OIPA), with specific authority to investigate issues and recommend solutions. The OIPA submits its first annual report for the year 2011-2012.[118] | |

| 2010 | July 17 | Violence | 48-year-old Fred Collins is shot by BART police and Oakland police near the Fruitvale BART station.[119][98] | Fruitvale |

| 2010 | August 27 | Connectivity (cellular) | BART announces that it has eliminated the mobile phone dead zone at the 19th Street, 12th Street/Oakland City Center and Lake Merritt stations along with all the tunnels in between (including the Oakland Wye). There is now continuous cellular connectivity from Balboa Park to downtown San Francisco, through the Transbay Tube, and all through the Oakland underground network for major carriers.[120] | 19th Street, 12th Street/Oakland City Center, Lake Merritt |

| 2010 | October 20 | Construction | BART celebrates groundbreaking of the Oakland Airport Connector (OAC) project, connecting the Coliseum station with the Oakland International Airport.[18] | Coliseum, Oakland International Airport |

| 2010 | October 29 | Construction | BART has an official groundbreaking ceremony for the eBART extension, from the current terminus at Pittsburg/Bay Point to the city of Antioch. The extension will run separate electric trains rather than extend the current routes.[18] | |

| 2010 | November 4 | Ridership record | BART records 522,200 daily riders, a record high, partly because of the San Francisco Giants World Series victory parade.[18] | |

| 2010 | Report | This is the earliest year for which BART's annual Report to Congress is available online. It is unclear if BART previously submitted reports to Congress.[121][122] | ||

| 2011 | February 19 | New stations | The West Dublin/Pleasanton station opens after several years of delays. It is an infill station, located on the Dublin/Pleasanton line between Castro Valley and Dublin/Pleasanton. It is the second infill station in the BART system after Embarcadero.[123] | |

| 2011 | March, April | Construction | BART receives $19 million from the Metropolitan Transportation Commisssion in toll revenue for the East Contra Costa County Extension Project, and begins construction on the project. The project involves a diesel eBART extension from the current northeast terminus of Pittsburg/Bay Point through Pittsburg, Antioch, Oakley, and Brentwood, to the Byron/Discovery Bay.[124][125] | |

| 2011 | April 13 | Team | BART announces that General Manager Dorothy Dugger is quitting with extra compensation of $958,000 (severance of $600,000 and extra compensation of $350,000 for a smooth transition), and BART is beginning the search for a replacement. Dugger's last day at work would be April 22, 2011.[126][127][128] The announcement comes after a Board vote in February to fire Dugger,[129] which the Board then backtracked on after legal concerns are raised.[130] | |

| 2011 | May 11 | Information for riders | BART launches an improved mobile website at m.bart.gov with location features and bike directions.[78] | |

| 2011 | August 31 | Team | Grace Crunican, who had previously worked at the Seattle Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, and Oregon Department of Transportation becomes the new General Manager of BART.[131][132][133] The Board had almost finalized the decision to appoint her by early August 2011.[134] | |

| 2011 | July 3 | Violence | Charles Blair Hill, a homeless man, is shot dead by a BART police officer at Civic Center after throwing a bottle at the officer.[135][136][98] | Civic Center |

| 2011 | August 11 | Protests | To control protests (against the killing of Charles Blair Hill) in downtown San Francisco stations, BART turns off cellular service for a limited period of time in those stations.[137][98] | Downtown San Francisco stations (Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell Street, Civic Center) |

| 2011 | November 18 | Train cars | In response to reports about the unsanitary nature of the cushioning used on BART train seats and the difficulty of cleaning carpeted floors, BART embarks on a project to replace the seats with vinyl seats as well as remove carpeting from the floors.[58] | |

| 2011 | Report | The 2011 Ambient Air Test Report is published. This is the first of two Ambient Air Test Reports available on the BART website, and shows that BART meets the thresholds for asbestos and respiratory dust set by the California Occupational Safety and Health Adminisrtation (Cal/OSHA).[121][138] | ||

| 2011 | Construction | Construction begins on the eBART extension from Pittsburg/Bay Point station to Antioch. The two new stations being built on this extension are the Pittsburg Center and Antioch stations.[139] | Pittsburg/Bay Point, Pittsburg Center, Antioch | |

| 2012 | April 9 | Information for riders | BART launches a new Twitter account, @SFBARTAlert, to tweet automated service advisories. These match the advisories sent via SMS subscription and SMS on-demand. The existing BART Twitter account @SFBART will continue to be used for human-controlled messaging.[140] | |

| 2012 | May 10 | Train cars | The BART Board of Directors votes unanimously to award a $896 million contract (plus applicable taxes and escalation contingencies) to Bombardier Transportation to design and construct 410 train cars. The cars will be 100% assembled in the United States, with at least 66% American parts.[18] The selection of Bombardier is from three bidders, based on technical capabilities and low cost, with Bombardier's bid 12% cheaper ($104 million cheaper) than the second lowest bid.[141] | |

| 2012 | June | Team | Alicia Trost becomes the Communications Department Manager for the BART District, which also includes the title of chief BART spokesperson. Trost's comments would be included in a lot of news coverage of BART over the subsequent years.[142] | |

| 2012 | July 1 (announcement: May 18) | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. The inflation-based fare increase is 1.4% and is the last of four inflation-based fare increases from 2006 to 2012 that were approved by the BART Board in May 2003. The minimum fare is now $1.75 (no change) and the excursion fare is now $5.25 (up from $5.20).[143][144] | |

| 2013 | February 28 | Fares | The BART Board approves continued inflation-based fare increases, with increases slated for the years of 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. "The increase is calculated based on the average rate of inflation over the two year period minus 0.5% for BART’s commitment to productivity improvements." The increases are expected to raise an additional $325 million in revenue over the next eight years, and will help fund BART's capital funding needs. BART will also shift to demand-based parking, with a minimum parking cost of $1 and a 50-cent increase or decrease every 6 months for parking lots that are full and have less than 95% occupancy respectively over the 6-monthe period.[145] | |

| 2013 | November | Information for riders | BART rebuilds its website using the open-source platform Drupal. This would lead it to win the 2014 Blue Drop Award for best government website.[146][147] | |

| 2013 | July–September | Data, Report | The first of BART's quarterly performance reports (prepared by the Engineering & Operations Committee) is available for data in this period. The report is titled "BART Quarterly Performance Report 2014 Q1" as it was published in December 2013, which is 2014 Q1 in the United States fiscal year.[121][148] | |

| 2013 | October 19 | Accident | A BART train strikes and kill two workers inspecting a dip in the tracks between Walnut Creek and Pleasant Hill BART staitons. The train has no passengers and is being operated for training of substitute workers. Reports suggest that the driver spotted the workers, shouted at them, and tried to stop the train but it was going too fast (60 to 70 mph) and could not stop in time.[149][150] A NTSB investigation blames BART's "simple approval" practice where workers can enter the tracks after checking with BART's Operations Control Center, with no additional measures in place. In response, BART phases out simple approvals, sets a 27 mph speed limit on trains running in parts of the system where workers are on the tracks, and requires a 32-hour training program every 2 years for all BART workers who get onto the tracks.[151] | Walnut Creek, Pleasant Hill |

| 2013 | October 24 | Vehicles and devices on BART | The BART Board votes unanimously to modify BART's Bike Rules. Effective December 1, 2013, BART will allow bikes on all trains at all times—with the exception of the peak commute hours (7 am to 9 am and 4:30 pm and 6:30 pm) when bikes will not be allowed to board the first three cars of any train. The first three car rule provides an option for those who want to avoid bikes altogether. Existing rules, such as no bikes in the first train car, no bikes on crowded trains, etc. still apply. The decision is after three pilots, the first one starting with bikes being allowed on Fridays, and the latest an extended five month pilot starting July 1 of the policy now being officially adopted.[152] | |

| 2014 | January 1 (announcement: December 11, 2013) | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. This is the first of a series of four inflation-based fare increases approved by the BART Board in 2013 (the other three will be in 2016, 2018, and 2020); the increase is 5.2%. The minimum fare is now $1.85 (up from $1.75) and the excursion fare is now $5.55 (up from $5.25).[153][154] | |

| 2014 | November 22 | New stations | BART opens (for revenue service) its Oakland International Airport station and its Oakland Airport Connector (OAC) connecting the station with Coliseum station. OAC does not use the standard BART tracks or cars, but rather, uses automated guideway transit (AGT). The route has a fee of $6, and although part of the BART system, using this route along with another BART route does not offer any price savings: if the fare for a trip from a station to Coliseum is $x, then the fare from the station to the Oakland International Airport (by combining that trip and AirBART) is $(x + 6). It replaces a $3 bus shuttle called AirBART.[155] | Oakland International Airport, Coliseum |

| 2014 | December 30 | Connectivity (Internet) | BART cancels its contract with WiFi Rail Inc., the provider who had a 20-year contract starting 2009 to deliver wi-fi across the BART system. BART blames WiFi Rail Inc.'s slow progress and poor connectivity even in the areas where it has launched, while WiFi Rail Inc. says that it was hammered by lack of approval from BART to make the neded improvements and expansions. A lawsuit by WiFi Rail Inc. is still pending as of 2018.[156][157][158][159] | |

| 2015 | January 2 | Train cars | BART completes the transition to the new vinyl seats, begun in 2011 in response to complaints about the unsanitary cushioned seats and the extra cleaning costs.[160] | |

| 2015 | August and September | Track maintenance and noise levels | Over the weekends of August 1-2 and Labor Day Weekend (September 5-7), BART does some major track maintenance in the Transbay Tube, replacing, straightening, and flattening large sections of track, cleaning rail insulators, and replacing interlocking ties. After the first of the two track maintenances, Based on social media posts by users, BART reports that riders are experiencing lower noise levels in the Transbay Tube.[161] | Transbay Tube |

| 2015 | August 10 | Train cars | BART completes the removal of carpets from floors in all its train cars. The project was initiated in 2011 in response to concerns about unsanitary conditions as well as the extra cleaning costs.[162] The A, B, and C2 cars now feature vinyl flooring in either grey or blue coloring, while the C1 cars feature a spray-on composite flooring. | |

| 2015 | September 14 | Service frequency | BART makes some enhancements to its service frequencies, including running the Richmond line an extra hour in the evening, and adding extra trains for the morning and evening rush hour.[163][164] | |

| 2015 | Data | BART conducts a Station Profile Study, to understand the profile of riders at each of its stations. This updates data previously collected in 2008.[165] | ||

| 2016 | January 1 (announcement December 2, 2015) | Fares | New, increased BART fares are effective from this date. This is the second of four scheduled inflation-based fare increases, with the increase being 3.4% (the previous increase was on January 1, 2014, and the remaining increases would be in 2018 and 2020). The minimum fare is now $1.95 (up from $1.85) and the excursion fare is now $5.75 (up from $5.55).[166][167] | |

| 2016 | January 9 | Violence | A homicide occurs at West Oakland station.[168] The case would reveal that many cameras on train cars are decoys.[169] The case goes unsolved for a long time.[170] | West Oakland |

| 2016 | January 14 | Train cars | An undercover investigation by the San Francisco Chronicle shows that the majority of security cameras on train cars are decoys. This investigation is done after it is discovered that the camera on the train car of a murder was a decoy.[169][171] | |

| 2016 | March 17 to April 5 | Service disruption | On March 17, BART suddenly shuts down train service between North Concord/Martinez and Pittsburg/Bay Point stations, due to electric issues causing damage to train cars. It establishes a bus bridge between the stations.[172] On March 21, BART resumes limited train service during rush hours, while still operating a bus bridge at other times.[173] Regular service is restored on April 5.[174] On March 17, the first day of service disruption, Taylor Huckaby, a 27-year-old agency communications officer, starts tweeting with the hashtag #ThisIsOurReality, highlighting BART's systematic problems, blaming growth beyond the initial expectations and design of the BART system, and pointing to the urgent need for more funding for BART to solve the problems.[175][176] |

North Concord/Martinez, Pittsburg/Bay Point |

| 2016 | June 30, July, September | Train cars, construction | BART unveils train cars for the diesel eBART East Contra Costa County Project extension, and does some test runs along the extension from Pittsburg/Bay Point to Antioch. The new stations, till Antioch, are expected to open for revenue service in 2017 or 2018.[177][178] A video of a test run is uploaded to the Bay Area Transit News YouTube channel on September 22.[179] | Pittsburg/Bay Point, Pittsburg, Antioch |

| 2016 | October | Report | BART publishes a report "BART's Role in the Region", describing its role in the San Francisco Bay Area, its plan for the future, and the resources it needs to execute that plan.[180] The report comes shortly before Measure RR, a proposition to give BART a $3.5 billion infrastructure, is put up for the vote. | |

| 2016 | November 7 | Book | The book BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System by Michael J. Healy is published by Heyday Books.[181][182] Healy served as BART's agency spokesman and had been with BART from November 1971 until his retirement in 2004.[183] | |

| 2016 | November 8 | Referendum | San Francisco Bay Area voters approve Measure RR, providing a $3.5 billion infrastructure bond to BART for system repairs.[184] The bond would be backed by a tax levied on the three counties in the BART district, and would increase property taxes over a term of 30 to 40 years. Estimated average cost per household is $35 to $55 per year. This is the third time BART has issued general obligation bonds, the first time being the $792 million bond in 1962 for initial system construction (Proposition A), and the second time being the $980 million for the Earthquake Safety Program (Proposition AA).[185] The vote shares in the three counties are: 59.5% in Contra Costa County, 81.1% in San Francisco, and 70.8% in Alameda County, giving an average of 70.1%.[184][186] | |