Timeline of immigration detention in the United States

This timeline covers immigration detention in the United States.

It is a complement to the timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States and timeline of immigrant processing and visa policy in the United States.

See also List of detention sites in the United States for a list of detention centers.

Visual data

Google Trends

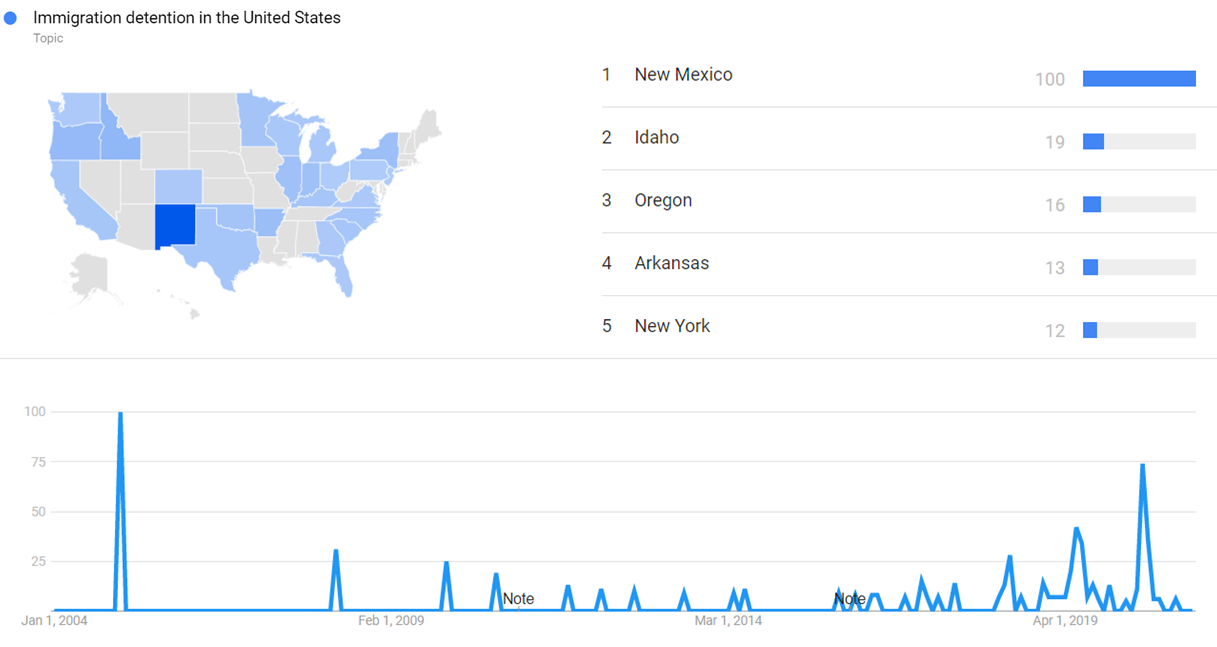

The image below shows Google Trends data in United States for Immigration detention in the United States (Topic) from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by state and displayed on map.[1]

Wikipedia Views

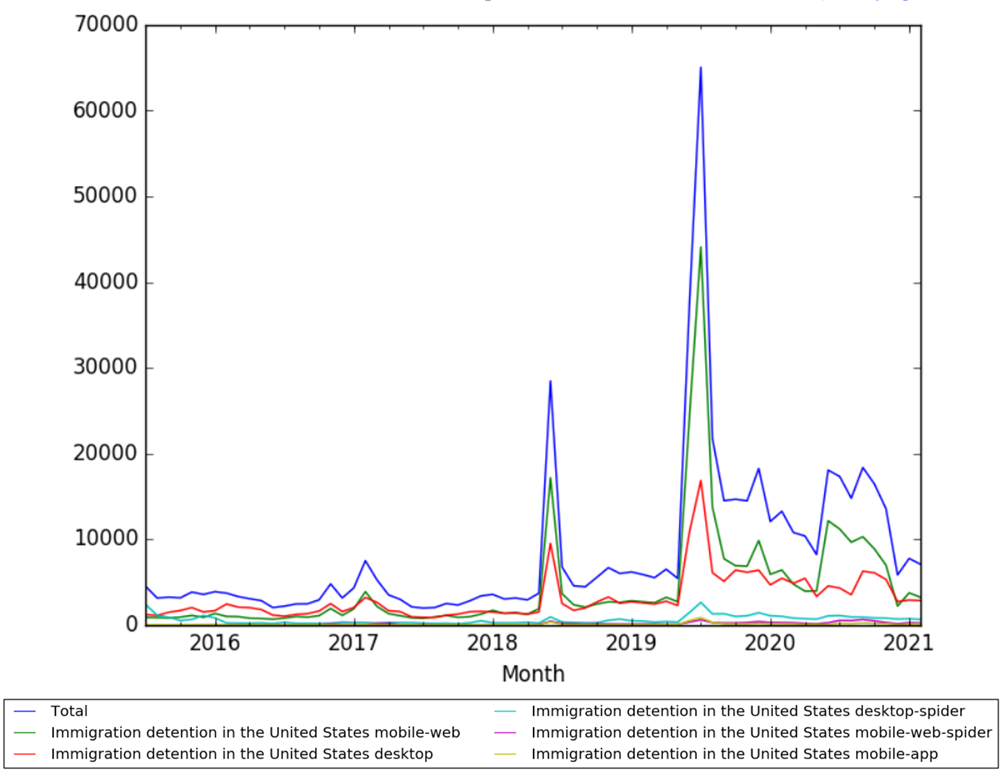

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Immigration detention in the United States, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app from July 2015; to February 2021.[2]

Full timeline

For the affected agencies column: ICE is shorthand for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; CBP is shorthand for U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

| Year | Month and date (if available) | Event type | Affected agencies (past, and present equivalents) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1892 | Immigration inspection station | Ellis Island becomes an immigration inspection station, handling immigrants arriving via the Atlantic. Immigrants could be temporarily detained upon arrival for closer examination, or to hold till they are deported. | ||

| 1902 | Immigration inspection station | The Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital is opened. It is both a general hospital and a contagious disease hospital. It also serves as a detention facility for new immigrants deemed unfit to enter the United States or held back for further examination. | ||

| 1910 | Immigration inspection station | Angel Island Immigration Station, an immigrant inspection facility with a detention center, opens for operations. It handles immigrants arriving via the Pacific. | ||

| 1984 | Detention center | ICE | The Varick Street Federal Detention Facility opens in Manhattan, New York. The detention center would ultimately be closed in 2010 after protests by inmates and pressure from advocacy groups.[3] | |

| 1997 | January 28 | Agreement | Executive branch | During the presidency of Bill Clinton, an agreement is reached regarding the permissible conditions for detaining child migrants, commonly called the Flores Agreement or Flores Settlement. This is a follow-up to the Supreme Court case Reno v. Flores. The three obligations identified for the government are: (1) The government is required to release children from immigration detention without unnecessary delay to, in order of preference, parents, other adult relatives, or licensed programs willing to accept custody. (2)If a suitable placement is not immediately available, the government is obligated to place children in the "least restrictive" setting appropriate to their age and any special needs. (3) The government must implement standards relating to the care and treatment of children in immigration detention.[4] |

| 2000 | September | Detention standards | ICE | A set of National Detention Standards (NDS) is issued that establishes "consistent conditions of confinement, program operations and management expectations" within the immigration detention system.[5] These would be the operational standards for detention centers to strive for until the introduction of new standards (PBNDS) in 2008.[6] |

| 2001 | June 28 | Court ruling | Zadvydas v. Davis is decided. The court rules that the plenary power doctrine does not authorize the indefinite detention of immigrants under order of deportation whom no other country will accept. To justify detention of immigrants for a period longer than six months, the government was required to show removal in the foreseeable future or special circumstances. | |

| 2003 | March 1 | Organizational restructuring | Immigration and Naturalization Services and U.S. Department of Homeland Security | The Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) (that was under the Department of Justice) is disbanded. Its functions are divided into three sub-agencies of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). |

| 2003 | Detention center | The Willacy County Regional Detention Center opens for operations in Raymondville, Texas, operated by Management and Training Corporation under contract with the United States Marshal Service. | ||

| 2004 | Detention center | The Stewart Detention Center opens for operations in Lumpkin, Georgia. | ||

| 2004 | Detention center | The Northwest Detention Center opens for operations in Tacoma, Washington, operated by Correctional Services Corporation on contract with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. | ||

| 2005 | May | Detention center | The South Texas Detention Facility, a privately operated prison, opens for operation in Pearsall, Texas as the Pearsall Immigration Detention Center. The prison houses people for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement as well as United States Marshal Service. | |

| 2005 | October | Detention center expansion plan | Michael Chertoff, then Secretary of Homeland Security, calls for an increase in detention center capacity so that the United States immigration enforcement can hold people in detention between the time of catching them and the time of their immigration hearings, and does not need to resort to catch and release.[7] | |

| 2006 | July | Chertoff indicates in House committee testimony that an infusion of funding for more immigration detention has allowed DHS to detain almost all non-Mexican illegal immigrants.[8] | ||

| 2008 | Detention standards | ICE | ICE revises its National Detention Standards (NDS) released in 2000 to create a new set of standards called Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS), that, "developed in coordination with agency stakeholders, prescribe both the expected outcomes of each detention standard and the expected practices required to achieve them."[9] These would be the operational standards till the release of revised standards in 2011.[6] | |

| 2008 | October | Detention center | ICE, New York City Bar Association | The New York City Bar Association receives a petition signed by 100 men in the Varick Street Federal Detention Facility in Manhattan, New York, describing "cramped, filthy quarters where dire medical needs were ignored and hungry prisoners were put to work for $1 a day" according to a New York Times' article published in November 2009.[3] |

| 2009 | November 2 | Detention center | ICE, New York City Bar Association (City Bar Justice Center) | A report by the City Bar Justice Center of the New York City Bar Association calls for all immigrant detainees to be provided with counsel.[3][10] Later in the month, an article in Fordham Law Review looks at the Varick Street detention facility as a case study in systematic barriers to legal representation.[11] |

| 2010 | February (approx) | Detention center | ICE | ICE announces its plans to close the Varick Street Federal Detention Facility in Manhattan, New York and relocate those currently held in it to prisons in New Jersey; Varick Street would only be used as a temporary holding location for a maximum of 12 hours per person. However, plans to close the place run into trouble due to challenges relocating people with medical and mental health challenges.[12] While there are some positive reactions, advocates push for deeper structural changes whereby people would be detained less; concerns are also raised about how relocating detainees would deprive them of their existing relationships with counsel based in New York.[13][14][15] |

| 2011 | Detention standards | ICE | ICE releases an updated version of its Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) for its detention centers. ICE states that "PBNDS 2011 is crafted to improve medical and mental health services, increase access to legal services and religious opportunities, improve communication with detainees with limited English proficiency, improve the process for reporting and responding to complaints, and increase recreation and visitation."[16][6] | |

| 2011 | August | Detention center | ICE | The East Wing of the Adelanto Detention Center, a detention facility managed by GEO Group for ICE, opens for operation. The facility had previously been a state prison for adult male inmates before the GEO Group purchased it in 2010 and contracted with ICE in May 2011 to use it for immigration detention. The West Wing would open in July 2012. |

| 2013 | Detention center | CBP (Border Patrol) | Clint Border Patrol Station opens as a migrant detention facility four miles north of the Mexico-U.S. border in Clint, Texas. It would be called "the public face of the chaos on America’s southern border" in a 2019 New York Times piece.[17] | |

| 2014 | Detention center | CBP | The Ursula detention center (official name "Central Processing Center"), the largest detention center operated by Customs and Border Protection, opens for operation in McAllen, Texas. In June 2018, it gained notoriety for the practice of keeping children in large cages made of chain-link fencing.[18] | |

| 2014 | December | Detention center (family detention) | The South Texas Family Residential Center opens in Dilley, South Texas. It has a capacity of 2,400 and is intended to detain mainly women and children from Central America. It is managed by the Corrections Corporation of America.[19] | |

| 2016 | Detention standards | ICE | ICE revisese its 2011 Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) to "ensure consistency with federal legal and regulatory requirements as well as prior ICE policies and policy statements." The revision is reflected through updates in the 2011 PBNDS on the ICE website, rather than a separate set of standards.[16] | |

| 2018 | June 14 | Detention center (temporary shelter) | DHS/ICE | The Tornillo tent city appears to have started operation around this time, as a temporary shelter to detain migrants. It would be shut down in January 2019. |

| 2019 | Detention standards | ICE | ICE releases its 2019 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities. According to ICE: "These detention standards will apply to the approximately 45 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Intergovernmental Service Agreement (IGSA) facilities currently operating under the NDS, approximately 35 United States Marshals Service (USMS) facilities used by ICE and which ICE inspects against the NDS, as well as approximately 60 facilities (both IGSA and USMS) which do not reach the threshold for ICE annual inspections – generally those with an Average Daily Population of less than 10."[20] | |

| 2020 | Detention standards | ICE | ICE releases its 2020 Family Residential Standards.[21] |

References

- ↑ "Immigration detention in the United States". Google Trends. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration detention in the United States". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bernstein, Nina (November 1, 2009). "Immigrant Jail Tests U.S. View of Legal Access". New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "The Flores Settlement: A Brief History and Next Steps". Human Rights First. February 19, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ "2000 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "ICE Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. February 24, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Chertoff: End 'Catch and Release' at Borders". Associated Press via Fox News. October 18, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Chertoff hails end of let-go policy". Washington Times. July 28, 2006. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "2008 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "NYC Bar Association Calls for Right to Counsel for Immigrant Detainees". City Bar Justice Center. November 2, 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Markowitz, Peter. "Barriers to Representation for Detained Immigrants Facing Deportation: Varick Street Detention Facility, A Case Study". Fordham Law Review. 78 (2).

- ↑ Bernstein, Nina (February 23, 2010). "Illness Hinders Plans to Close Immigration Jail". New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Statement to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Regarding Detainees at Varick Federal Detention Facility". February 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Hing, Julianne (February 25, 2010). "Varick Is Closing, But That's Not The Answer to Our Broken Detention System. The Varick Federal Detention Facility is days away from closure, and this should be good news.". ColorLines. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Varick Street Detention Facility to Close by End of February". March 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "2011 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Romero, Simon; Kanno-Youngs, Zolan; Fernandez, Manny; Borunda, Daniel; Montes, Aaron; Dickerson, Caitlin (2019-07-06). "Hungry, Scared and Sick: Inside the Migrant Detention Center in Clint, Tex.". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ↑ Frej, Willa (2018-06-18). "These Are The Texas Immigration Center Photos Stirring Anti-Trump Outrage". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "South Texas immigration detention center set to open". 15 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "2019 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Family Residential Standards 2020". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.