Difference between revisions of "Timeline of yellow fever"

From Timelines

(→Big Picture) |

(→Big Picture) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

| 2000s || Yellow fever vaccine is incorporated into the routine childhood vaccinations of several South American and African countries, thus decreasing the number of persons susceptible to the disease over time.<ref name="Timeline of yellow fever" /> | | 2000s || Yellow fever vaccine is incorporated into the routine childhood vaccinations of several South American and African countries, thus decreasing the number of persons susceptible to the disease over time.<ref name="Timeline of yellow fever" /> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Recent years || Between 2007 and 2016, 14 countries would complete preventive yellow fever vaccination campaigns.<ref name="Yellow fever fact sheets">{{cite web|title=Yellow fever fact sheets|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs100/en/|publisher=[[wikipedia:WHO|WHO]]|accessdate=20 February 2017}}</ref> Today, Yellow fever causes 200,000 infections and 30,000 deaths every year, with nearly 90% of these occurring in [[wikipedia:Africa|Africa]]. | + | | Recent years || Between 2007 and 2016, 14 countries would complete preventive yellow fever vaccination campaigns.<ref name="Yellow fever fact sheets">{{cite web|title=Yellow fever fact sheets|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs100/en/|publisher=[[wikipedia:WHO|WHO]]|accessdate=20 February 2017}}</ref> Today, Yellow fever causes 200,000 infections and 30,000 deaths every year, with nearly 90% of these occurring in [[wikipedia:Africa|Africa]]. Forty-four countries in Africa, South and Central America are within the modern yellow fever endemic zone, with almost 900 million people at risk of infection.<ref name="Yellow Fever: A Reemerging Threat" /> |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 12:52, 23 April 2021

The content on this page is forked from the English Wikipedia page entitled "Timeline of yellow fever". The original page still exists at Timeline of yellow fever. The original content was released under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License (CC-BY-SA), so this page inherits this license.

For a comprehensive treatment of the subject, see History of yellow fever.

This is a timeline of yellow fever. Major events such as historical epidemics and medical developments are described.

Contents

Big Picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 17th century | Yellow fever infection spreads as the shipping industry and global commerce expand. Large numbers of African slaves, infected with yellow fever, also spread the disease.[1] Early recorded epidemics of yellow fever occur in Barbados, Cuba, Guadeloupe and Mexico.[2] |

| 18th century | Yellow fever spreads to Europe.[3] Outbreaks are also reported from areas within West Africa, with far fewer outbreaks being identified in East Africa.[4] |

| 19th century | Public health experts continue to believe yellow fever is transmitted by contact with infected patients.[1] At the close of the century, yellow fever is a known and feared pestilence of the western hemisphere and the coastal regions of West Africa, for which no cause or effective treatment is known.[5] Josiah C. Nott and Carlos Finlay link yellow fever to mosquitoes as disease vectors.[2] |

| 1900s | Early in the century, aedes aegypti is established as the yellow fever disease vector, and eradication of it in a number of countries, notably Panama, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina, leads to the disappearance of urban yellow fever.[6] Yellow fever is eradicated from the United States.[7][3] |

| 1930s | Yellow fever vaccines are developed.[3] Massive vaccination campaigns would follow.[2] |

| 1940s–1950s | Mass campaigns are conducted using the 17D vaccine in South America and the French neurotropic vaccine in French-controlled areas of Africa. Large scale vaccination campaigns would reduce yellow fever incidence for several decades.[8][3][7] In the 1940s and early 1950s, nearly 40 million doses of FNV would be administered in French-speaking countries of West Africa.[7] |

| 1960s | Yellow fever outbreaks occur in both Africa and the Americas. Thousands of cases are reported in West Africa, where vaccination coverage is weak or absent.[3][7] |

| 1980s onwards | Incidence of yellow fever increases in Africa. Between 1980 and 2012, 150 yellow fever outbreaks in 26 countries in Africa would be reported to the World Health Organization.[8][3] Early in the 1990s, global estimates of 200,000 cases and 30,000 deaths annually are reported, around 90% of which occur in Africa.[8] |

| 2000s | Yellow fever vaccine is incorporated into the routine childhood vaccinations of several South American and African countries, thus decreasing the number of persons susceptible to the disease over time.[3] |

| Recent years | Between 2007 and 2016, 14 countries would complete preventive yellow fever vaccination campaigns.[9] Today, Yellow fever causes 200,000 infections and 30,000 deaths every year, with nearly 90% of these occurring in Africa. Forty-four countries in Africa, South and Central America are within the modern yellow fever endemic zone, with almost 900 million people at risk of infection.[7] |

Visual Data

Google Trends

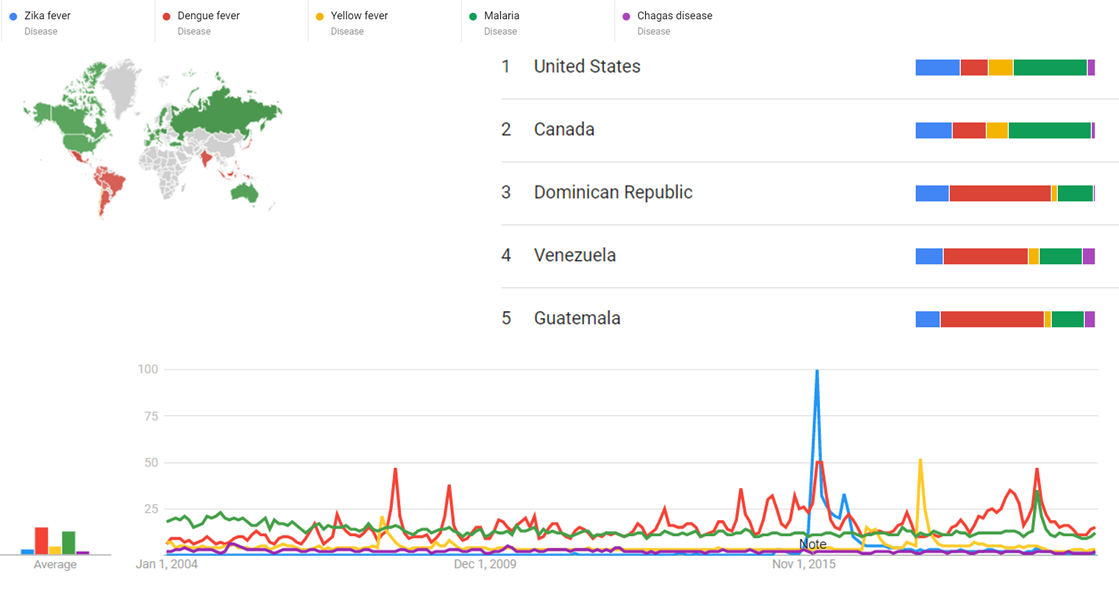

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Zika fever (Disease), Dengue fever (Disease), Yellow fever (Disease), Malaria (Disease) and Chagas disease (Disease), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[10]

Google Ngram Viewer

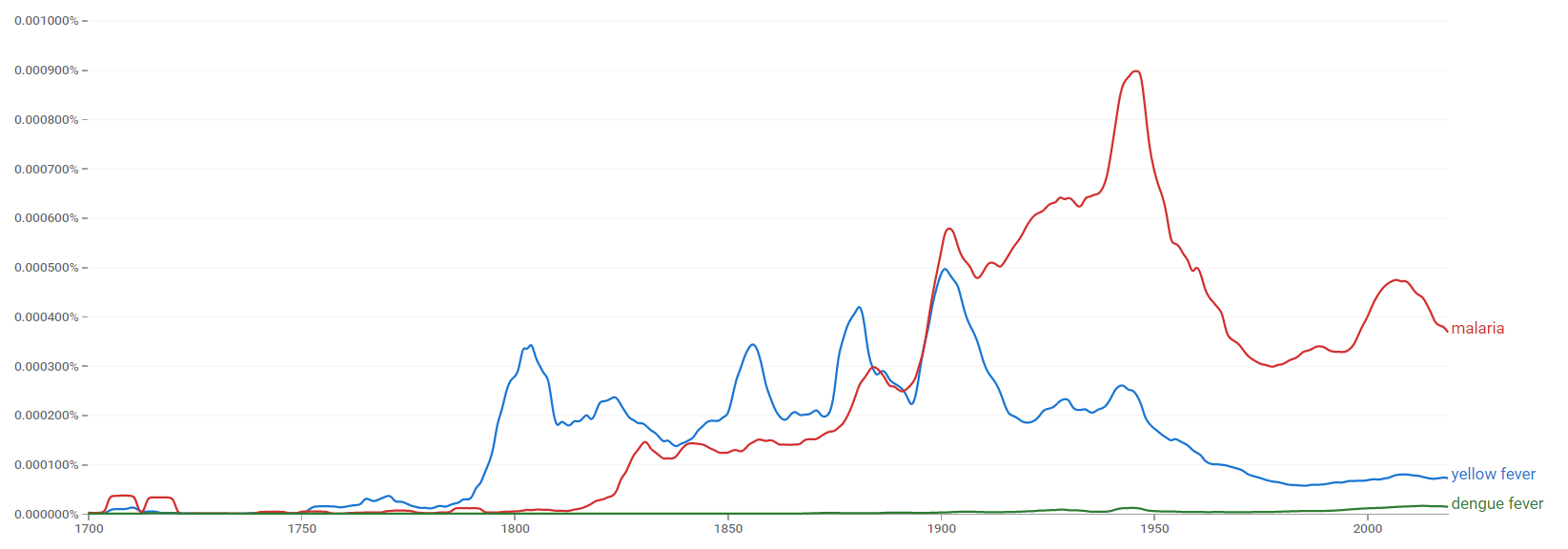

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Yellow fever, malaria and dengue fever, from 1700 to 2019.[11]

Wikipedia Views

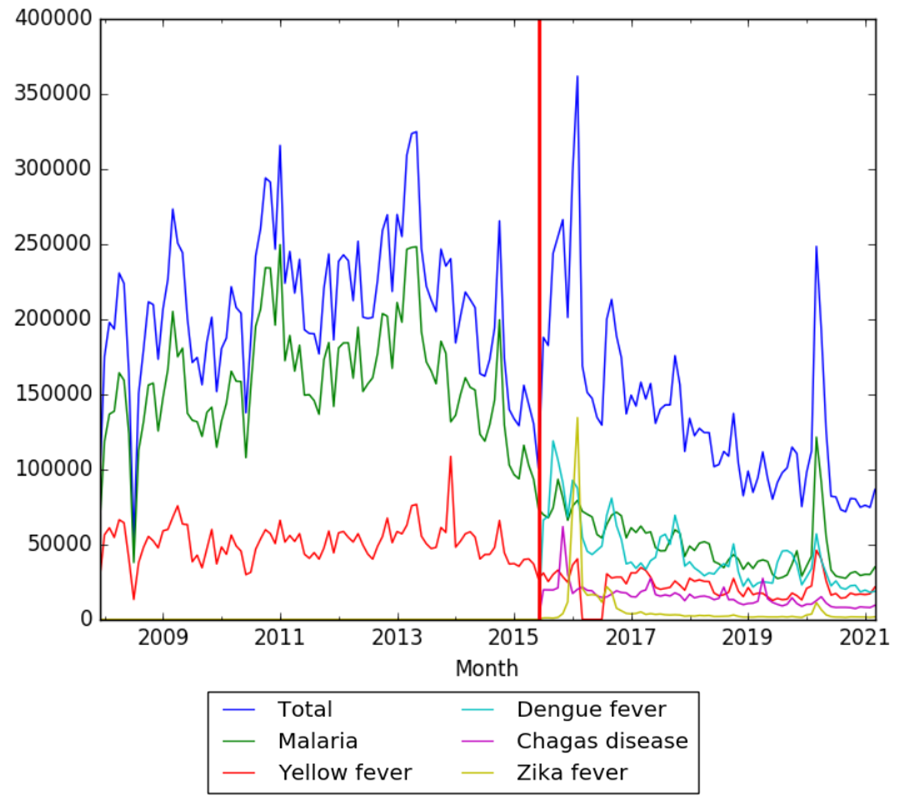

The comparative chart below shows pageviews on desktop of the English Wikipedia articles Zika fever, Dengue fever, Yellow fever, Malaria and Chagas disease, from December 2007 to March 2021.[12]

Full timeline

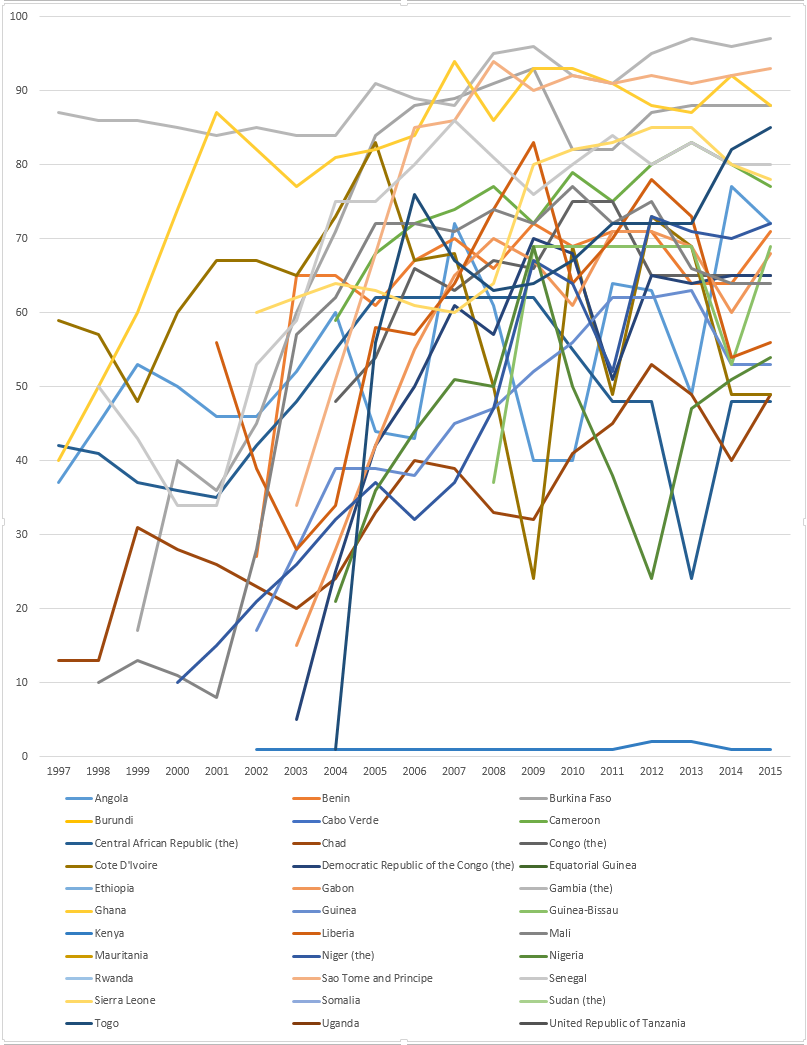

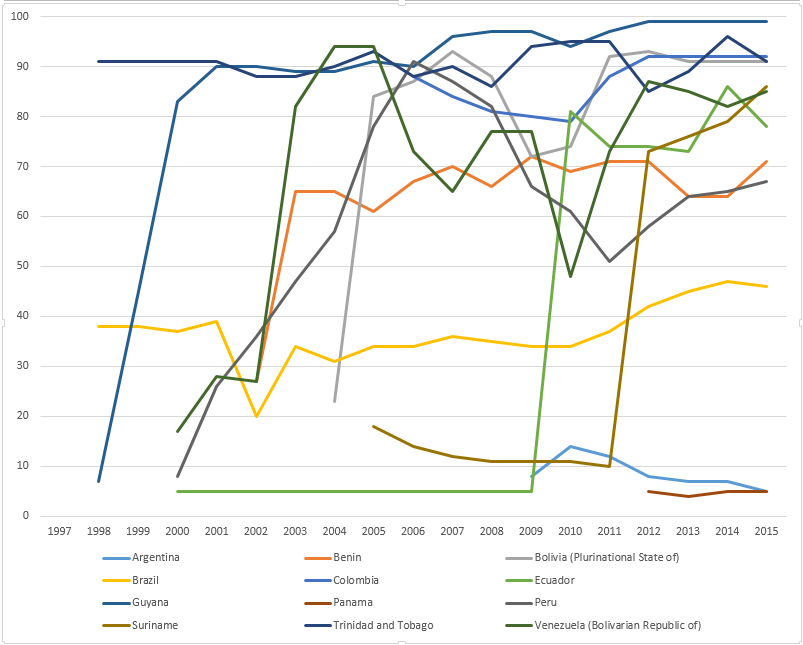

WHO-UNICEF estimates of yellow fever vaccine coverage in% in African countries, for the period 1997-2015.[13]

WHO-UNICEF estimates of yellow fever vaccine coverage in% in American countries, for the period 1997-2015.[13]

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3000 BP | Probable origin of yellow fever in Africa, according to modern sequence analysis of the viral genome.[14] | Africa | |

| 1494 | Epidemic | Disease outbreaks similar in signs and symptoms to yellow fever are reported from Canary islands and Cape Verde off the coast of Africa, and sometimes in coastal countries such as Gambia, and Sierra Leone.[2] | West Africa |

| 1647 | Epidemic | The first definitive outbreak of yellow fever in the Americas happens in the island of Barbados.Template:Fix/category[citation needed] | Barbados |

| 1648 | Epidemic | An outbreak is recorded by Spanish colonists in the Yucatán Peninsula, where the indigenous Mayan people call the illness xekik ("blood vomit"). Yellow fever is found in Mayan manuscripts describing an outbreak of the disease in the Yucatan peninsula.[7][3] | Mexico |

| 1649 | Epidemic | Yellow fever is brought in ships to and from Africa and the West Indies, to Gibraltar.[2] | Gibraltar |

| 1668 | Epidemic | The first yellow fever outbreak in English-speaking North America occurs in New York City.[3] | United States |

| 1669 | Epidemic | English colonists in Philadelphia and the French in the Mississippi River Valley record major outbreaks of yellow fever.Template:Fix/category[citation needed] | United States |

| 1685 | Epidemic | Brazil suffers its first yellow fever epidemic, in Recife.[15] | Brazil |

| 1730 | Epidemic | 2,200 deaths are reported in Cadiz, Spain, due to yellow fever, followed by outbreaks in French and British seaports.[3] | |

| 1750 | Epidemic | The term yellow fever is first used by author Griffin Hughes in his book Natural History of Barbadoes.[2][14] | Barbados |

| 1778 | Epidemic | Yellow fever outbreak reportedly decimates English troops stationed at Saint-Louis, Senegal.[2] | Senegal |

| 1793–1805 | Epidemic | Severe yellow fever epidemics afflict Boston, New York City and Philadelphia.[16] | United States |

| 1799 | Organization | Largely in response to the 1793 yellow fever epidemic, the Philadelphia Lazaretto Quarantine Station on Tinicum Island is built. The station is designed to quarantine infected travelers headed for Philadelphia by ship.[17] | United States (Philadelphia) |

| 1800 | Epidemic | Yellow fever epidemic breaks out in Spain. Over 60,000 deaths are associated.[2] | Spain |

| 1839–1860 | Epidemic | About 26,000 people in New Orleans contract yellow fever.[1] Three successive epidemics, from 1853 to 1855, kill about 14,000 people in the city.[16] | United States |

| 1848 | Scientific development | American physician Josiah C. Nott floats the idea that mosquitoes may be serving as agents for the dissemination of both yellow fever and malaria (However, the full credit for the theory would be given to Carlos Finlay).[2] | |

| 1878 | Epidemic | About 20,000 people die in an epidemic in towns of the Mississippi River Valley and its tributaries.[16] | United States |

| 1881 | Scientific development | Cuban physician, Carlos Finlay, acting on a theory that mosquitoes carry the yellow fever virus, conducts an experiment with mosquitoes that harbor the disease after biting yellow fever patients. He lets the mosquitoes bite an experimental subject, who then would come down with yellow fever, thus proving the hipothesis. Finlay would be recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it is transmitted through mosquitoes.[7][3] | Cuba |

| 1898 | Epidemic | During the Spanish–American War, reportedly more soldiers from the United States Army die of yellow fever than in battle. This would prompt military efforts for further research and the formation of the Reed Yellow Fever Commission led by Walter Reed, an American army surgeon.[3] | Cuba |

| 1898 | Yellow fever vector aedes aegypti is seen in Brazil for the first time. Aedes aegypti would be responsible for turning yellow fever into an urban disease in the Americas.[18] | Brazil | |

| 1900 | Scientific development | The Reed Yellow Fever Commission proves that yellow fever infection is transmitted to humans by mosquito Aedes aegypti, which would later be determined to be the vector of the urban transmission cycle of yellow fever virus.[3] | |

| 1905 | Epidemic | The last outbreak of yellow fever in the United States occurs in New Orleans.[7][3] | United States |

| 1906 | Epidemic | An estimated 85% of Panama Canal workers are hospitalized with either malaria or yellow fever. Workers are so terrified of yellow fever that they fly the construction site in droves at the first hint of the disease. Tens of thousands of workers die.[1] However, following the demonstration that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are responsible for transmission of the yellow fever virus to humans, intense sanitation programs begin in Panama and Havana, Cuba. These efforts would lead to the eradication of the disease in these areas, and enable the completion of the Panama Canal by 1906.[3] | Panama, Cuba |

| 1907 | To date, yellow fever has acquired 152 synonyms, including American Pestilence, Barbados Distemper, Continua Putrida, Icteroides Caroliniensis, Yellow Jack, etc.[2] | ||

| 1909 | United States Army physician William C. Gorgas states that yellow fever can be eradicated, meaning the disease as a specific entity can be eliminated.[19] | ||

| 1915 | Organization | The Rockefeller Yellow Fever Commission of the Rockefeller Foundation is formed.[20] | United States |

| 1925 | Organization | The Rockefeller Foundation expands its yellow fever activities to Africa, and establishes the West African Yellow Fever Commission The expedition, based near Lagos, is to determine whether African yellow fever is the same as yellow fever in South America, to find the causative agent (including further search for Leptospira), and to study its epidemiology.[5] | Africa |

| 1927 | Scientific development | Rockefeller Yellow Fever Commission researchers first isolate the causative agent of yellow fever disease, the yellow fever virus, from a Ghanaian patient named Asibi. The Asibi yellow fever virus strain is still widely used by scientists today.[7][2] | |

| 1928 | Epidemic | The last documented urban yellow fever epidemic in the Americas occurs in Rio de Janeiro.[7] | Brazil |

| 1937 | Medical development | South African virologist Max Theiler and colleagues develop a live-attenuated vaccine strain, designated 17D, for immunization against yellow fever. The yellow fever vaccine used today derives from the original 17D strain. Theiler would be later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his life-saving research. The French neurotropic vaccine is also developed in the 1930s, from a strain isolated in Senegal in 1927.[7][3][21] | |

| 1940 | Epidemic | The first epidemic confirmed in East Africa breaks out in central Sudan.[4] | Sudan |

| 1942 | Epidemic | Major epidemics of hepatitis occur in United States and Allied troops who have received yellow fever vaccine. The source of the infection would be traced to the serum, or clear fluid in the blood, that is used in the vaccine.[22][23] | Europe |

| 1943 | Epidemic | Yellow fever epidemic breaks out in Bolivia.[21] | Bolivia |

| 1950 | Report shows high rate of postvaccinal encephalitis following administration of the yellow fever vaccine to infants.[3] | ||

| 1954 | Epidemic | The last documented aedes aegypti-borne yellow fever epidemic in the western hemisphere occurs in Trinidad.[6] | Trinidad and Tobago |

| 1955 | UNICEF and the World Health Organization determine that yellow fever is a worldwide issue that must be tackled together.[19] | ||

| 1960–1962 | Epidemic | Yellow fever epidemic breaks out in Ethiopia.100,000 cases and 30,000 deaths are reported.[2] | Ethiopia |

| 1969 | Epidemic | Yellow fever epidemic breaks out in the Jos Plateau, Nigeria. 397 patients were hospitalized and 123 deaths are confirmed.[24] | Nigeria |

| 1982 | The French neurotropic vaccine is abandoned due to high rates of postvaccinal encephalitis the vaccine causes. The 17D vaccine becomes the standard for use in immunization for yellow fever worldwide.[3] | ||

| 1988 | Program launch | The World Health Organization recommends that vaccination against yellow fever be included in routine infant immunization programs (as of 2009, 22 African countries and 14 South American countries have done so).[7] | |

| 1992 | Epidemic | A large yellow fever outbreak is confirmed in the Rift Valley Province of Kenya,[4] a country that has been free of YF for more than 50 years.[2] | Kenya |

| 1998–1999 | Epidemic | 147 cases of jungle yellow fever are reported in Brazil.[18] | Brazil |

| 1999 | Epidemic | Yellow fever re-emerges in parts of Brazil that have been silent for several decades. This would challenge prevention strategies and result in frequent revision of yellow fever vaccine recommendations.[25] | Brazil |

| 2005 | Organization | The Yellow Fever Initiative is launched as a collaboration between the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) with support from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI Alliance), with aims at securing the precarious yellow fever vaccine supply by creating a vaccine stockpile to be used in outbreak response campaigns as well as to increase the vaccination coverage in the most affected areas by implementation of large preventive mass vaccination campaigns in 12 of the most affected countries in West Africa.[8] | Africa |

| 2008 | Epidemic | Yellow fever breaks out in central and southeastern Brazil, northeastern Argentina and Paraguay (after a 34-year absence).[25][7] | Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay |

| 2010 | Epidemic | A major outbreak of Yellow Fever is reported in five districts in Northern Uganda. 181 cases including 45 deaths are reported.[26] | Uganda |

| 2011 | Program launch | Following an outbreak of yellow fever in northern Uganda in December 2010, the Ministry of Health conducts a massive emergency vaccination campaign. 177 vaccination posts are created, 354 health workers and 590 volunteers from 295 villages are identified and trained.[27] | Uganda |

| 2013 | Epidemic | African countries report an estimated 130,000 cases of yellow fever with fever and jaundice or haemorrhage, including 78,000 deaths.[8] | Africa |

| 2016 | Epidemic | A yellow fever outbreak in Angola spreads to the Democratic Republic of Congo, with 3,867 suspected cases in Angola and 2,269 suspected cases in DRC.[1] | Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo |

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Brink, Susan. "Yellow Fever Timeline: The History Of A Long Misunderstood Disease". npr.org. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Tomori, Oyewale. "Yellow fever in Africa: public health impact and prospects for control in the 21st century". Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 "Timeline of yellow fever". cdc.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Yellow Fever Outbreak, Southern Sudan, 2003". PMC 3320285

. doi:10.3201/eid1009.030727.

. doi:10.3201/eid1009.030727.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Frierson, J. Gordon. "The Yellow Fever Vaccine: A History". PMC 2892770

.

.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Yellow Fever Vaccine Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP)". cdc.gov. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 Gardner, Christina L.; Ryman, Kate D. "Yellow Fever: A Reemerging Threat". PMC 4349381

. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2010.01.001.

. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2010.01.001.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Hay, Simon I. (ed.). "Yellow Fever in Africa: Estimating the Burden of Disease and Impact of Mass Vaccination from Outbreak and Serological Data". PMC 4011853

. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001638.

. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001638.

- ↑ "Yellow fever fact sheets". WHO. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "Zika fever, Dengue fever, Yellow fever, Malaria and Chagas disease". Google Trends. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Yellow fever, malaria and dengue fever". books.google.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "Zika fever, Dengue fever, Yellow fever, Malaria and Chagas disease". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "WHO-UNICEF estimates of YFV coverage". WHO. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Immunisation against infectious diseases. Great Britain: Department of Health. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Bethell, Leslie. Colonial Brazil. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 DUFFY, JOHN. "YELLOW FEVER IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY" (PDF). nih.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "The history of vaccines". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Prata, Aluízio. "Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz". Departamento de Medicina Tropical, Faculdade de Medicina do Triângulo Mineiro. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762000000700031. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Eradication of Yellow Fever in New Orleans". medianola.org. Tulane University. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "William C. Gorgas". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Bundschuh, Matthias; Groneberg, David A; Klingelhoefer, Doris; Gerber, Alexander. "Yellow fever disease: density equalizing mapping and gender analysis of international research output". PMC 3843536

. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-6-331.

. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-6-331.

- ↑ York Morris, Susan. "The History of Hepatitis C: A Timeline". healthline.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Thomas, Roger E.; Lorenzetti, Diane L.; Spragins, Wendy. "Mortality and Morbidity Among Military Personnel and Civilians During the 1930s and World War II From Transmission of Hepatitis During Yellow Fever Vaccination: Systematic Review". PMC 3673520

. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301158.

. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301158.

- ↑ CAREY, D. E.; BRES, P; KEMP, G. E.; TROUP, J. M.; WHITE, H. A.; SMITH, E. A.; ADDY, R. F.; FOM, A. L.; PIFER, J.; JONES, E. M.; SHOPE, R. E. "Epidemiological aspects of the 1969 yellow fever epidemic in Nigeria" (PDF). Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Gubler, Duane J. (ed.). "Yellow Fever Outbreaks in Unvaccinated Populations, Brazil, 2008–2009". PMC 3953027

. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002740.

. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002740.

- ↑ Mbonye, Anthony K; et al. "Ebola Viral Hemorrhagic Disease Outbreak in West Africa- Lessons from Uganda". PMC 4209631

. doi:10.4314/ahs.v14i3.1. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

. doi:10.4314/ahs.v14i3.1. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ Bagonza, James; Rutebemberwa, Elizeus; Mugaga, Malimbo; Tumuhamye, Nathan; Makumbi, Issa. "Yellow fever vaccination coverage following massive emergency immunization campaigns in rural Uganda, May 2011: a community cluster survey". PMC 3608017

. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-202.

. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-202.