Difference between revisions of "Timeline of tungsten"

| (34 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This is a '''timeline of {{w|tungsten}}'''. | + | This is a '''timeline of {{w|tungsten}}''', attempting to describe historic events related to the discovery, science and industrial development of the metal. |

==Big picture== | ==Big picture== | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

! Time period !! Development summary | ! Time period !! Development summary | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 16th century || Tungsten is first discovered in the 16th century by tin miners, who find and then recognize the metal as a newly useful and undiscovered asset.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten">{{cite web |title=The History and Uses of Tungsten |url=https://www.larsonjewelers.com/The-History-and-Uses-of-Tungsten.aspx |website=larsonjewelers.com |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref> | + | | 16th century || Tungsten is first discovered in the 16th century in {{w|Saxony}} by {{w|tin}} miners, who find and then recognize the metal as a newly useful and undiscovered asset.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten">{{cite web |title=The History and Uses of Tungsten |url=https://www.larsonjewelers.com/The-History-and-Uses-of-Tungsten.aspx |website=larsonjewelers.com |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="Tungsten History">{{cite web |title=Tungsten > History |url=http://www.almonty.com/tungsten/history/ |website=almonty.com |accessdate=11 August 2018}}</ref> |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 18th century || Chemists begin identifying the elements that make up mater. In this century tungsten is first isolated.<ref name="Chronology of Science">{{cite book |last1=Rezende |first1=Lisa |title=Chronology of Science |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=079t8r9RIcIC&pg=PA153&dq=%22Elhuyar%22+%221783%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjVxIfKmuPcAhVCH5AKHYCfBd0Q6AEIODAD#v=onepage&q=%22Elhuyar%22%20%221783%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 20th century || In the 1930s, new applications arise for tungsten compounds in the oil industry for the hydrotreating of crude oils. In the 1940s, during {{w|World War II}}, the Germans are the first to use tungsten carbide core in high velocity armor piercing projectiles. In the 1950s, tungsten is added into superalloys to improve performance. In the 1960s, new catalysts are born containing tungsten compounds to treat exhaust gases in the oil industry.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> | | 20th century || In the 1930s, new applications arise for tungsten compounds in the oil industry for the hydrotreating of crude oils. In the 1940s, during {{w|World War II}}, the Germans are the first to use tungsten carbide core in high velocity armor piercing projectiles. In the 1950s, tungsten is added into superalloys to improve performance. In the 1960s, new catalysts are born containing tungsten compounds to treat exhaust gases in the oil industry.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 21st century || Currently, most tungsten resources are found in China, South Korea, Bolivia, Great Britain, Russia and Portugal, as well as in California and Colorado. About 80% of world’s supply is controlled by China.<ref name="Facts About Tungsten"/> Today, tungsten carbide is extremely widespread, with applications including metal cutting, machining of wood, plastics, composites, soft ceramics, chipless forming, mining, construction, rock drilling, structural parts, wear parts, and military components. Tungsten-steel alloys are used in the production of rocket engine nozzles, and superalloys containing tungsten are used in turbine blades and wear-resistant parts and coatings.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

==Full timeline== | ==Full timeline== | ||

| Line 19: | Line 23: | ||

! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Country/region | ! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Country/region | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1779 || || Irish chemist {{w|Peter Woulfe}} examines a mineral from Sweden and realizes it contains a new type of metal.<ref name="Facts About Tungsten">{{cite web |title=Facts About Tungsten |url=https://www.livescience.com/38997-facts-about-tungsten.html |website=livescience.com |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref> || | + | | 1556 || Discovery || German mineralogist {{w|Georgius Agricola}} notes a material he calls ''lupi spuma'' ("wolf's foam"), which in [[w:German language|German]] is ''wolf rahm''. The mineral ore is today known as {{w|wolframite}} and is one of the main sources of tungsten. This explains the symbol "W" for the element.<ref name="The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective"/> || {{w|Germany}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1750 || Discovery || Tungsten ore (now called ''{{w|scheelite}}'') is discovered in the Bispberg´s iron mine in the Swedish province [[W:Dalarna|Dalecarlia]].<ref name="HISTORY OF TUNGSTEN"/><ref>{{cite web |title=tungsten mine |url=http://www.debouchage-wiame.be/29284/tungsten-mine/ |website=debouchage-wiame.be |accessdate=27 August 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1757 || Scientific development || Swedish chemist {{w|Axel Fredrik Cronstedt}} describes a light heavy mineral. He names it “tung sten” in [[w:swedish language|Swedish]], meaning “heavy stone”.<ref name="History">{{cite web |title=History |url=https://www.vitalmetals.com.au/metal-markets/tungsten/history/ |website=vitalmetals.com.au |accessdate=11 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="Tungsten History"/><ref name="Tungsten processing">{{cite web |title=Tungsten processing |url=https://www.britannica.com/technology/tungsten-processing |website=britannica.com |accessdate=27 August 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1779 || Scientific development || Irish chemist {{w|Peter Woulfe}} examines a mineral from Sweden and realizes it contains a new type of metal.<ref name="Facts About Tungsten">{{cite web |title=Facts About Tungsten |url=https://www.livescience.com/38997-facts-about-tungsten.html |website=livescience.com |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective"/> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1781 || Scientific development || German chemist {{w|Carl Wilhelm Scheele}} continues the research on the new metal and isolates an acidic white oxide.<ref name="Facts About Tungsten"/><ref name="The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective"/> Scheele is the first to produce tungsten acid from tungsten ore.<ref name="History"/><ref name="The Hard Facts about Tungsten">{{cite web |title=The Hard Facts about Tungsten |url=https://www.mi-techmetals.com/about-us/tungsten-history |website=mi-techmetals.com |accessdate=11 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="Tungsten History"/><ref>{{cite book |title=History of Chemistry |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=n1JdDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA217&lpg=PA217&dq=%22in+1781%22+%22tungsten%22+%22bergman%22&source=bl&ots=_S-rgs4Ryi&sig=_e28_rJKBxpAzdLgUtV6haZ5rao&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjwmNyljozdAhXLf5AKHTnPA6YQ6AEwD3oECAIQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22in%201781%22%20%22tungsten%22%20%22bergman%22&f=false}}</ref><ref name="Tungsten processing"/> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1781 || || " | + | | 1781 || Scientific development || The name "tungsten" is suggested by chemist {{w|Tobern Bergman}}.<ref name="The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective">{{cite book |last1=Ede |first1=Andrew |title=The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=9FcyamrwwnMC&pg=PA125&dq=%22Elhuyar%22+%221783%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjVxIfKmuPcAhVCH5AKHYCfBd0Q6AEIVTAI#v=onepage&q=%22Elhuyar%22%20%221783%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1783 || || | + | | 1783 || Scientific development || Tungsten is first isolated by Spanish brothers {{w|Fausto Elhuyar}} and {{w|Juan José Elhuyar}}. They isolate the metal oxide from wolframite and reduce it to tungsten metal by heating it with carbon.<ref>{{cite book |last1=DK |title=1000 Inventions and Discoveries |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=IztIBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA110&dq=%22Elhuyar%22+%221783%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtwNi0mePcAhUGvJAKHf4JABoQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22Elhuyar%22%20%221783%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref><ref name="The Hard Facts about Tungsten"/><ref name="The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies">{{cite book |last1=Rollinson |first1=Carl L. |title=The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=Bkr-BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA742&dq=%22Elhuyar%22+%221783%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtwNi0mePcAhUGvJAKHf4JABoQ6AEIPjAE#v=onepage&q=%22Elhuyar%22%20%221783%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref> The brothers call the new metal ''wolfram''.<ref name="Chronology of Science"/><ref name="Tungsten processing"/> || {{w|Spain}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1820 || Scientific development || One of the two economically important minerals of tungsten is named “wolframite” by German mineralogist {{w|August Breithaupt}}.<ref name="History"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1821 || Scientific development || German mineralogist {{w|Karl Cäsar von Leonhard}} proposes the name “Scheelite” for the mineral CaWO<sub>4</sub>, in honour of {{w|Carl Wilhelm Scheele}}.<ref name="History"/><ref name="Tungsten History"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1847 || Technology || British Engineer Robert Oxland is granted a patent to prepare, form, and reduce tungsten to its metallic format.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten"/><ref name="Tungsten History"/><ref name="Tungsten processing"/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Percy |first1=John |title=Metallurgy: The Art of Extracting Metals from Their Ores, and Adapting Them to Various Purposes of Manufacture, Volume 2 |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ZGc3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA192&dq=%22in+1857%22+%22Robert+Oxland%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjygpbtmYzdAhUBhJAKHZ6KCfgQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22in%201857%22%20%22Robert%20Oxland%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior ..., Volume 4, Part 3 |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=vTRIAQAAMAAJ&q=%22in+1857%22+%22Robert+Oxland%22+%22tungsten%22&dq=%22in+1857%22+%22Robert+Oxland%22+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjygpbtmYzdAhUBhJAKHZ6KCfgQ6AEINzAD}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1847 || Application || Tungsten salts are used to make colored cotton and to make clothes used for theatrical and other purposes fireproof.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth">{{cite web |last1=DESJARDINS |first1=JEFF |title=The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth |url=http://www.visualcapitalist.com/history-of-tungsten-worlds-strongest-metal/ |website=visualcapitalist.com |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1855 || Application || Austrian chemist Franz Koller develops a tungsten steel.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten"/><ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/><ref name="The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies"/> || {{w|Austria}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1857 || Technology || Robert Oxland patents his process for producing tungsten steel.<ref name="Tungsten processing"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1858 || Application || Steels containing tungsten begin to be produced.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten"/><ref name="Tungsten History"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1868 || Application || Mushet starts to manufacture high-carbon-vanadium-manganese-tungsten steels in {{w|England}}.<ref name="The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies"/><ref name="HISTORY OF TUNGSTEN"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1895 || Scientific development || American inventor {{w|Thomas Edison}} finds that calcium tungstate is the substance with the best ability to fluoresce when exposed to {{w|X-ray}}s.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1900 || Application || A special mix of steel and tungsten is exhibited at the [[w:Exposition Universelle (1900)|World Exhibition]] in Paris.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1923 || || A German electrical bulb company submits a patent for tungsten carbide, or hardmetal. The carbide is made by "cementing" very hard tungsten monocarbide (WC) grains in a binder matrix of tough cobalt metal by liquid phase sintering. The resulting material combines high strenght, toughness and high hardness.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> || {{w|Germany}} | + | | 1904 || Application || Several European inventors almost simultaneously develop lamp filaments made with the metal tungsten.<ref name="Incandescent lamp with ductile tungsten filament">{{cite web |title=Incandescent lamp with ductile tungsten filament |url=http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_704238 |website=americanhistory.si.edu |accessdate=26 August 2018}}</ref> The first light bulbs using tungsten are patented in the year.<ref name="The History and Uses of Tungsten"/><ref name="The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies"/><ref name="Tungsten History"/> || |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1908 || Application || American physicist {{w|William D. Coolidge}} discovers that tungsten is an ideal filament material.<ref name="Facts About Tungsten"/> Coolidge invents a process for making tungsten filaments which (combined with other improvements) produce lamps two and a half times as efficient as those used before.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Boorstin |first1=Daniel J. |title=The Americans: The Democratic Experience |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=RicRyr47FMgC&pg=PT789&dq=%22in+1908%22+William+D.+Coolidge+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwitu7_m8OPcAhWKkJAKHUDrBtAQ6AEINjAD#v=onepage&q=%22in%201908%22%20William%20D.%20Coolidge%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Heerding |first1=A. |title=The History of N. V. Philips' Gloeilampenfabrieken: Volume 2, A Company of Many Parts |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=evg8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA164&dq=%22in+1908%22+William+D.+Coolidge+%22tungsten%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwitu7_m8OPcAhWKkJAKHUDrBtAQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22in%201908%22%20William%20D.%20Coolidge%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref><ref name="Tungsten processing"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1909 || Technology || Team led {{w|William D. Coolidge}} working at {{w|General Electric}} discover a process that creates ductile tungsten filaments through suitable heat treatment and mechanical working.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/><ref name="The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies"/><ref>{{cite web |title=Coolidge, William David (1873-1975) |url=http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/biographies/william-david-coolidge/ |website=harvardsquarelibrary.org |accessdate=26 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="Incandescent lamp with ductile tungsten filament"/><ref>{{cite book |title=Transition Elements: Advances in Research and Application: 2011 Edition |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=hAom8zU-a78C&pg=PA964&lpg=PA964&dq=%22in+1909%22+%22coolidge%22+%22tungsten%22&source=bl&ots=1ShksmWlCd&sig=BBlCqp8WDfL5uojxtPFGc-9BWtM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjB2aqX1ovdAhWMgJAKHamXAv4Q6AEwCXoECAAQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22in%201909%22%20%22coolidge%22%20%22tungsten%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1911 || Application || The Coolidge process is commercialized. In a short time, tungsten light bulbs would spread all over the world equipped with ductile tungsten wires.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1922 || Policy || Tungsten is placed on the first official Government list of strategic minerals in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |title=Materials Survey: Tungsten |publisher=United States. Business and Defense Services Administration |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=MbkfR95e7MoC&q=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1920..1940%22&dq=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1920..1940%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiFh7fxhePcAhUBUJAKHcHYB4kQ6AEIPDAD}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1923 || Application || A German electrical bulb company submits a patent for tungsten carbide, or hardmetal. The carbide is made by "cementing" very hard tungsten monocarbide (WC) grains in a binder matrix of tough cobalt metal by liquid phase sintering. The resulting material combines high strenght, toughness and high hardness.<ref name="The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth"/> || {{w|Germany}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1927 || Application || The Krupp Laboratory at {{w|Essen}}, Germany, discovers that a serviceable product could be produced when the normally brittle tungsten carbide is mixed with a cemented material.<ref name="Tungsten processing"/> || {{w|Germany}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1940 – 1945 || Application || Tungsten becomes a strategic metal during {{w|World War II}} as its resistance to high temperatures and its strengthening of alloys make it an important raw material for the arms industry.<ref name="Tungsten History"/> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1944 || Book || K C Li, founder of {{w|Wah Chang Corporation}} in the United States, publishes a picture in the ''Engineering & Mining Journal'' entitled: “40 Years Growth of the Tungsten Tree (1904 – 1944)” which illustrates the fast development of the various tungsten applications in the field of metallurgy and chemistry.<ref name="HISTORY OF TUNGSTEN">{{cite web |title=HISTORY OF TUNGSTEN |url=https://www.itia.info/history.html |website=itia.info |accessdate=11 August 2018}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1977 || Production || China is the biggest and most important tungsten ore concentrate supplier.<ref name="Tungsten: Properties, Chemistry, Technology of the Element, Alloys, and Chemical Compounds"/> || {{w|China}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1979 || Event || The first International Tungsten Symposium is held in {{w|Stockholm}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tungsten : proceedings of the First International Tungsten Symposium, Stockholm, September 5-7, 1979 / edited ... by Mining Journal Books Limited in co-operation with the Primary Tungsten Association and the Consumer Reporting Group, co-sponsors of the symposium. |url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10096953?q&versionId=11735156 |website=trove.nla.gov.au |accessdate=10 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="International Tungsten Symposium">{{cite web |title=International Tungsten Symposium |url=http://classify.oclc.org/classify2/ClassifyDemo?search-author-txt=%22International+Tungsten+Symposium%22 |website=classify.oclc.org |accessdate=26 August 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=International Tungsten Symposium (1st :, 1979 : Stockholm, Sweden) |url=https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1451990 |website=catalogue.nla.gov.au |accessdate=26 August 2018}}</ref> || {{w|Sweden}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1993 || Financial || The price of tungsten reaches historical minimum, as a result of the collapse of the communist world together with a sudden fall in the worldwide tungsten consumption.<ref name="Tungsten: Properties, Chemistry, Technology of the Element, Alloys, and Chemical Compounds">{{cite book |last1=Lassner |first1=Erik |last2=Schubert |first2=Wolf-Dieter |title=Tungsten: Properties, Chemistry, Technology of the Element, Alloys, and Chemical Compounds |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=GnPdBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA401&dq=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1960..1980%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwimm_2XjePcAhXDFZAKHZ0cCnEQ6AEIQjAE#v=onepage&q=%22tungsten%22%20%22in%201960..1980%22&f=false}}</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1995 || Production || Two countries, China (69%), and the former {{w|Soviet Union}} (19%), account for over 80 percent of the world's production of tungsten.<ref name="International Strategic Mineral Issues Summary Report--tungsten">{{cite book |last1=Werner |first1=Antony B. T. |last2=Sinclair |first2=W. D. |last3=Amey |first3=Earle B. |title=International Strategic Mineral Issues Summary Report--tungsten |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=Empks89XyocC&pg=PA12&dq=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1920..1940%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiFh7fxhePcAhUBUJAKHcHYB4kQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22tungsten%22%20%22in%201920..1940%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|China}}, Ex-{{w|USSR}} | | 1995 || Production || Two countries, China (69%), and the former {{w|Soviet Union}} (19%), account for over 80 percent of the world's production of tungsten.<ref name="International Strategic Mineral Issues Summary Report--tungsten">{{cite book |last1=Werner |first1=Antony B. T. |last2=Sinclair |first2=W. D. |last3=Amey |first3=Earle B. |title=International Strategic Mineral Issues Summary Report--tungsten |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=Empks89XyocC&pg=PA12&dq=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1920..1940%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiFh7fxhePcAhUBUJAKHcHYB4kQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22tungsten%22%20%22in%201920..1940%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|China}}, Ex-{{w|USSR}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2003 || Application || {{w|Ammonium paratungstate}}, ferrotungsten, {{w|tungsten carbonate}}, and {{w|tungsten oxide}} are major exported products from China.<ref>{{cite book |title=China Mining Laws and Regulations Handbook |publisher=International Business Publications, USA |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=MMqmv3OmX_QC&pg=SA9-PA11&lpg=SA9-PA11&dq=%22tungsten%22+%22in+1996..2006%22&source=bl&ots=twmIvobjKM&sig=L74lr51_3btn9z1LTE2i2g4xJhg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicnPvGgOTcAhUJxpAKHX5KCdsQ6AEwAnoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22tungsten%22%20%22in%201996..2006%22&f=false}}</ref> || {{w|China}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2009 || Application || Tungsten filament bulbs start being phased out in the {{w|European Union}}.<ref name="ddd">{{cite web |title=The Rise and Fall of the Tungsten Filament Lightbulb |url=https://mmta.co.uk/2015/04/01/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-tungsten-filament-lightbulb/ |website=mmta.co.uk |accessdate=26 August 2018}}</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

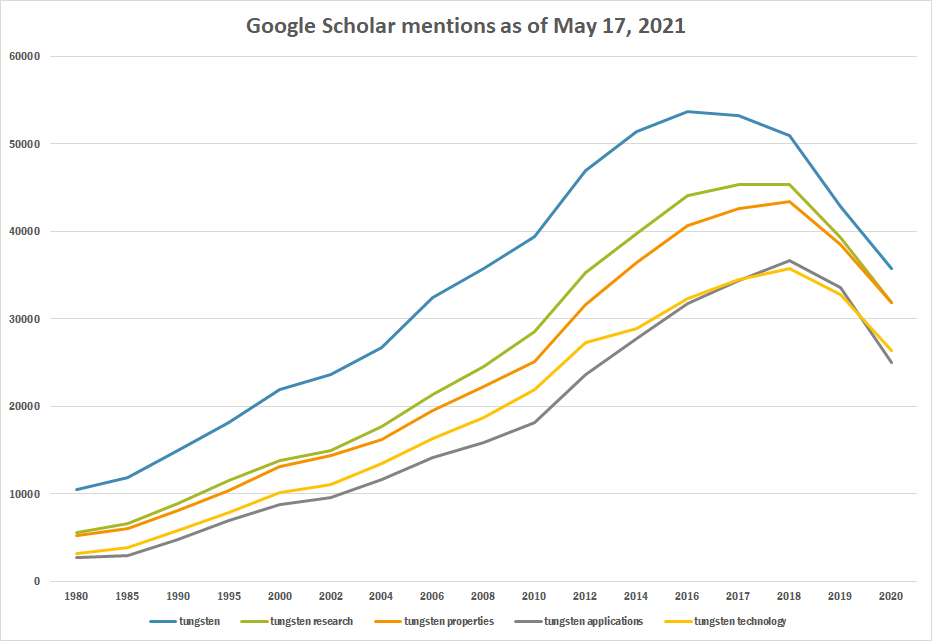

| + | The table below summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 17, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! tungsten | ||

| + | ! tungsten research | ||

| + | ! tungsten properties | ||

| + | ! tungsten applications | ||

| + | ! tungsten technology | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 10,500 || 5,590 || 5,280 || 2,770 || 3,170 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || 11,900 || 6,560 || 5,990 || 2,910 || 3,920 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 14,900 || 8,910 || 8,040 || 4,750 || 5,860 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || 18,200 || 11,500 || 10,400 || 6,920 || 7,910 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 21,900 || 13,800 || 13,100 || 8,820 || 10,100 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2002 || 23,600 || 15,000 || 14,400 || 9,570 || 11,100 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004 || 26,700 || 17,700 || 16,200 || 11,600 || 13,500 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || 32,400 || 21,400 || 19,500 || 14,100 || 16,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || 35,800 || 24,500 || 22,300 || 15,900 || 18,700 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 39,400 || 28,500 || 25,100 || 18,200 || 21,900 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || 47,000 || 35,300 || 31,600 || 23,600 || 27,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2014 || 51,400 || 39,700 || 36,400 || 27,700 || 28,900 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2016 || 53,700 || 44,100 || 40,700 || 31,700 || 32,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017 || 53,200 || 45,300 || 42,600 || 34,400 || 34,500 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || 51,000 || 45,400 || 43,400 || 36,700 || 35,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2019 || 42,800 || 39,300 || 38,500 || 33,600 || 32,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 35,800 || 31,900 || 31,900 || 25,000 || 26,400 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tungsten tb.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

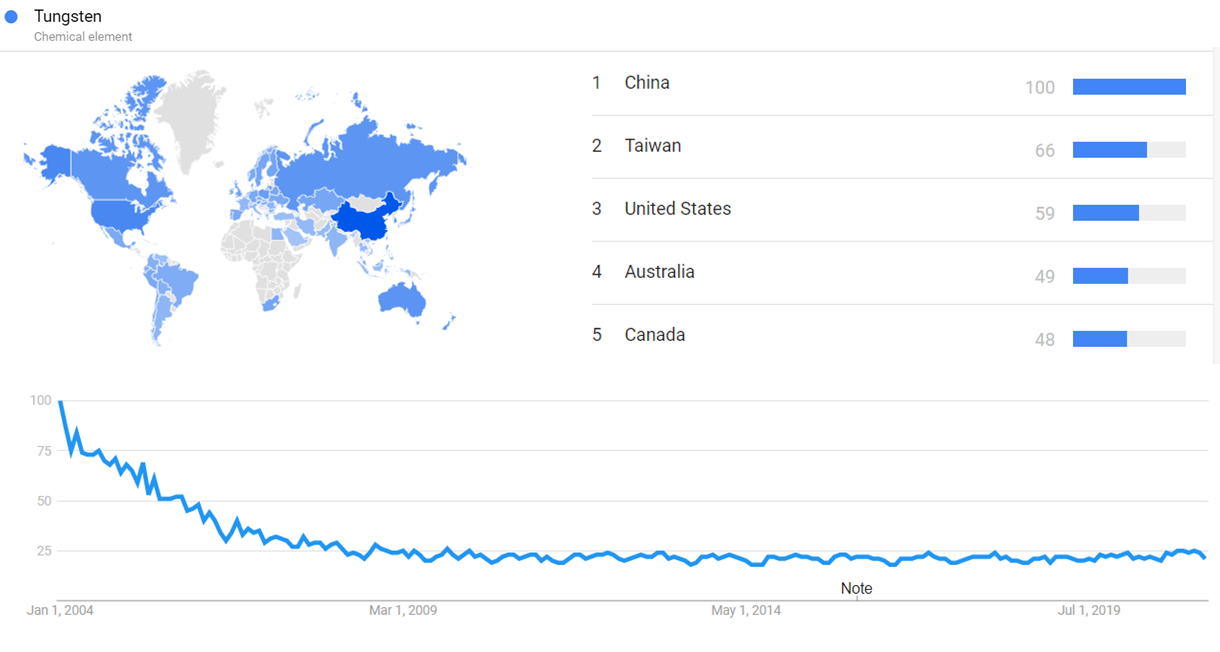

| + | === Google Trends === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Tungsten (Chemical element), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tungsten |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F025sk79 |website=Google Trends |access-date=27 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tungsten gt.png|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

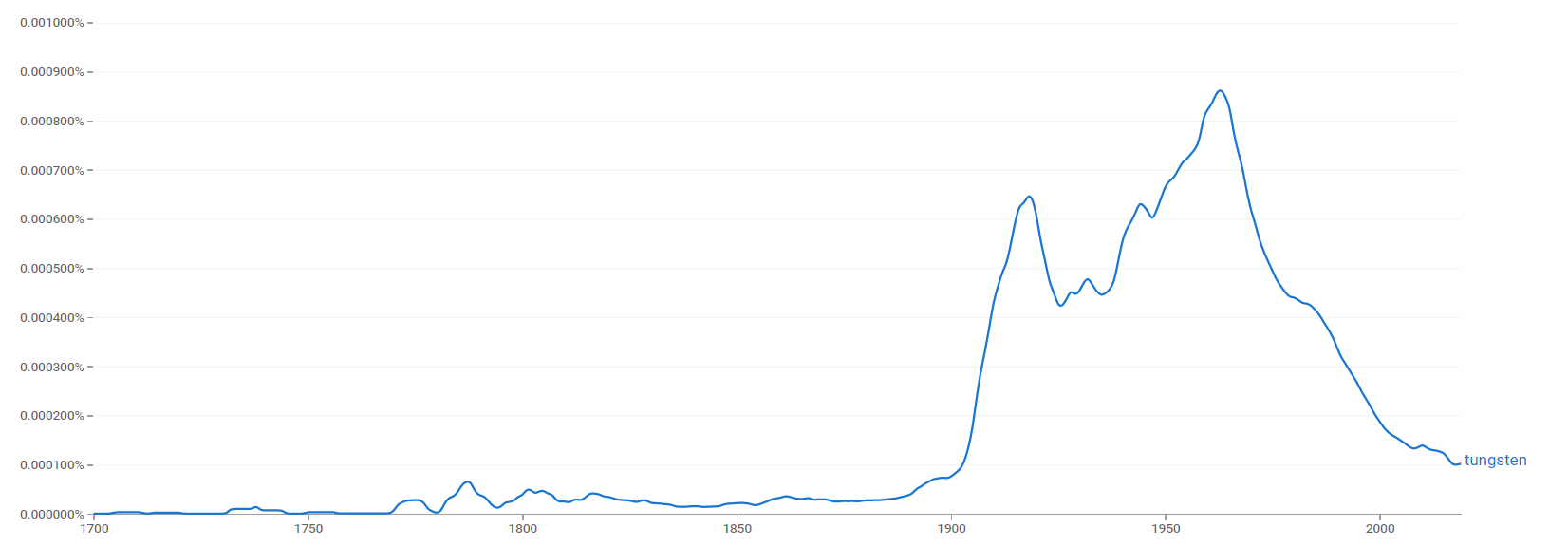

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Tungsten, from 1700 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tungsten |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=tungsten&year_start=1700&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2Ctungsten%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=27 April 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tungsten ngram.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

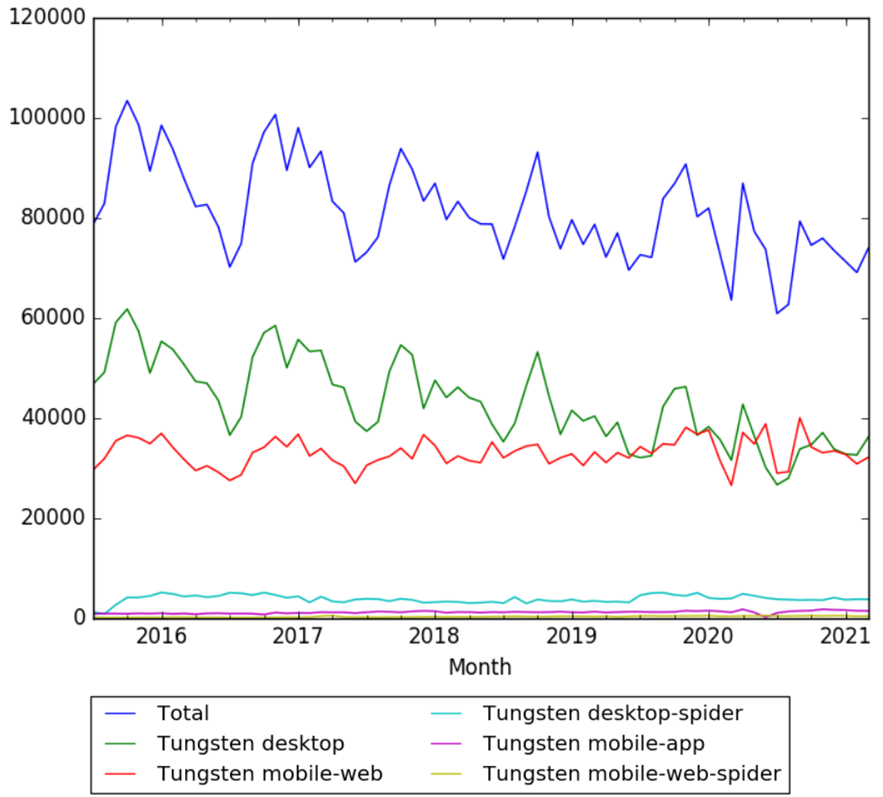

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Tungsten}}, from July 2015 to March 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tungsten |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Tungsten&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=27 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tungsten wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

==Meta information on the timeline== | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

| Line 55: | Line 164: | ||

===How the timeline was built=== | ===How the timeline was built=== | ||

| − | The initial version of the timeline was written by [[User: | + | The initial version of the timeline was written by [[User:Sebastian]]. |

{{funding info}} is available. | {{funding info}} is available. | ||

| Line 66: | Line 175: | ||

===What the timeline is still missing=== | ===What the timeline is still missing=== | ||

| − | + | ||

===Timeline update strategy=== | ===Timeline update strategy=== | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Timeline of cobalt]] | ||

| + | * [[Timeline of titanium]] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:49, 11 April 2024

This is a timeline of tungsten, attempting to describe historic events related to the discovery, science and industrial development of the metal.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 16th century | Tungsten is first discovered in the 16th century in Saxony by tin miners, who find and then recognize the metal as a newly useful and undiscovered asset.[1][2] |

| 18th century | Chemists begin identifying the elements that make up mater. In this century tungsten is first isolated.[3] |

| 20th century | In the 1930s, new applications arise for tungsten compounds in the oil industry for the hydrotreating of crude oils. In the 1940s, during World War II, the Germans are the first to use tungsten carbide core in high velocity armor piercing projectiles. In the 1950s, tungsten is added into superalloys to improve performance. In the 1960s, new catalysts are born containing tungsten compounds to treat exhaust gases in the oil industry.[4] |

| 21st century | Currently, most tungsten resources are found in China, South Korea, Bolivia, Great Britain, Russia and Portugal, as well as in California and Colorado. About 80% of world’s supply is controlled by China.[5] Today, tungsten carbide is extremely widespread, with applications including metal cutting, machining of wood, plastics, composites, soft ceramics, chipless forming, mining, construction, rock drilling, structural parts, wear parts, and military components. Tungsten-steel alloys are used in the production of rocket engine nozzles, and superalloys containing tungsten are used in turbine blades and wear-resistant parts and coatings.[4] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Country/region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1556 | Discovery | German mineralogist Georgius Agricola notes a material he calls lupi spuma ("wolf's foam"), which in German is wolf rahm. The mineral ore is today known as wolframite and is one of the main sources of tungsten. This explains the symbol "W" for the element.[6] | Germany |

| 1750 | Discovery | Tungsten ore (now called scheelite) is discovered in the Bispberg´s iron mine in the Swedish province Dalecarlia.[7][8] | Sweden |

| 1757 | Scientific development | Swedish chemist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt describes a light heavy mineral. He names it “tung sten” in Swedish, meaning “heavy stone”.[9][2][10] | Sweden |

| 1779 | Scientific development | Irish chemist Peter Woulfe examines a mineral from Sweden and realizes it contains a new type of metal.[5][6] | |

| 1781 | Scientific development | German chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele continues the research on the new metal and isolates an acidic white oxide.[5][6] Scheele is the first to produce tungsten acid from tungsten ore.[9][11][2][12][10] | Sweden |

| 1781 | Scientific development | The name "tungsten" is suggested by chemist Tobern Bergman.[6] | Sweden |

| 1783 | Scientific development | Tungsten is first isolated by Spanish brothers Fausto Elhuyar and Juan José Elhuyar. They isolate the metal oxide from wolframite and reduce it to tungsten metal by heating it with carbon.[13][11][14] The brothers call the new metal wolfram.[3][10] | Spain |

| 1820 | Scientific development | One of the two economically important minerals of tungsten is named “wolframite” by German mineralogist August Breithaupt.[9] | |

| 1821 | Scientific development | German mineralogist Karl Cäsar von Leonhard proposes the name “Scheelite” for the mineral CaWO4, in honour of Carl Wilhelm Scheele.[9][2] | |

| 1847 | Technology | British Engineer Robert Oxland is granted a patent to prepare, form, and reduce tungsten to its metallic format.[1][2][10][15][16] | United Kingdom |

| 1847 | Application | Tungsten salts are used to make colored cotton and to make clothes used for theatrical and other purposes fireproof.[4] | |

| 1855 | Application | Austrian chemist Franz Koller develops a tungsten steel.[1][4][14] | Austria |

| 1857 | Technology | Robert Oxland patents his process for producing tungsten steel.[10] | United Kingdom |

| 1858 | Application | Steels containing tungsten begin to be produced.[1][2] | |

| 1868 | Application | Mushet starts to manufacture high-carbon-vanadium-manganese-tungsten steels in England.[14][7] | United Kingdom |

| 1895 | Scientific development | American inventor Thomas Edison finds that calcium tungstate is the substance with the best ability to fluoresce when exposed to X-rays.[4] | United States |

| 1900 | Application | A special mix of steel and tungsten is exhibited at the World Exhibition in Paris.[4] | France |

| 1904 | Application | Several European inventors almost simultaneously develop lamp filaments made with the metal tungsten.[17] The first light bulbs using tungsten are patented in the year.[1][14][2] | |

| 1908 | Application | American physicist William D. Coolidge discovers that tungsten is an ideal filament material.[5] Coolidge invents a process for making tungsten filaments which (combined with other improvements) produce lamps two and a half times as efficient as those used before.[18][19][10] | United States |

| 1909 | Technology | Team led William D. Coolidge working at General Electric discover a process that creates ductile tungsten filaments through suitable heat treatment and mechanical working.[4][14][20][17][21] | United States |

| 1911 | Application | The Coolidge process is commercialized. In a short time, tungsten light bulbs would spread all over the world equipped with ductile tungsten wires.[4] | United States |

| 1922 | Policy | Tungsten is placed on the first official Government list of strategic minerals in the United States.[22] | United States |

| 1923 | Application | A German electrical bulb company submits a patent for tungsten carbide, or hardmetal. The carbide is made by "cementing" very hard tungsten monocarbide (WC) grains in a binder matrix of tough cobalt metal by liquid phase sintering. The resulting material combines high strenght, toughness and high hardness.[4] | Germany |

| 1927 | Application | The Krupp Laboratory at Essen, Germany, discovers that a serviceable product could be produced when the normally brittle tungsten carbide is mixed with a cemented material.[10] | Germany |

| 1940 – 1945 | Application | Tungsten becomes a strategic metal during World War II as its resistance to high temperatures and its strengthening of alloys make it an important raw material for the arms industry.[2] | |

| 1944 | Book | K C Li, founder of Wah Chang Corporation in the United States, publishes a picture in the Engineering & Mining Journal entitled: “40 Years Growth of the Tungsten Tree (1904 – 1944)” which illustrates the fast development of the various tungsten applications in the field of metallurgy and chemistry.[7] | United States |

| 1977 | Production | China is the biggest and most important tungsten ore concentrate supplier.[23] | China |

| 1979 | Event | The first International Tungsten Symposium is held in Stockholm.[24][25][26] | Sweden |

| 1993 | Financial | The price of tungsten reaches historical minimum, as a result of the collapse of the communist world together with a sudden fall in the worldwide tungsten consumption.[23] | |

| 1995 | Production | Two countries, China (69%), and the former Soviet Union (19%), account for over 80 percent of the world's production of tungsten.[27] | China, Ex-USSR |

| 2003 | Application | Ammonium paratungstate, ferrotungsten, tungsten carbonate, and tungsten oxide are major exported products from China.[28] | China |

| 2009 | Application | Tungsten filament bulbs start being phased out in the European Union.[29] |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The table below summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 17, 2021.

| Year | tungsten | tungsten research | tungsten properties | tungsten applications | tungsten technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 10,500 | 5,590 | 5,280 | 2,770 | 3,170 |

| 1985 | 11,900 | 6,560 | 5,990 | 2,910 | 3,920 |

| 1990 | 14,900 | 8,910 | 8,040 | 4,750 | 5,860 |

| 1995 | 18,200 | 11,500 | 10,400 | 6,920 | 7,910 |

| 2000 | 21,900 | 13,800 | 13,100 | 8,820 | 10,100 |

| 2002 | 23,600 | 15,000 | 14,400 | 9,570 | 11,100 |

| 2004 | 26,700 | 17,700 | 16,200 | 11,600 | 13,500 |

| 2006 | 32,400 | 21,400 | 19,500 | 14,100 | 16,300 |

| 2008 | 35,800 | 24,500 | 22,300 | 15,900 | 18,700 |

| 2010 | 39,400 | 28,500 | 25,100 | 18,200 | 21,900 |

| 2012 | 47,000 | 35,300 | 31,600 | 23,600 | 27,300 |

| 2014 | 51,400 | 39,700 | 36,400 | 27,700 | 28,900 |

| 2016 | 53,700 | 44,100 | 40,700 | 31,700 | 32,300 |

| 2017 | 53,200 | 45,300 | 42,600 | 34,400 | 34,500 |

| 2018 | 51,000 | 45,400 | 43,400 | 36,700 | 35,800 |

| 2019 | 42,800 | 39,300 | 38,500 | 33,600 | 32,800 |

| 2020 | 35,800 | 31,900 | 31,900 | 25,000 | 26,400 |

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Tungsten (Chemical element), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[30]

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Tungsten, from 1700 to 2019.[31]

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Tungsten, from July 2015 to March 2021.[32]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "The History and Uses of Tungsten". larsonjewelers.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Tungsten > History". almonty.com. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rezende, Lisa. Chronology of Science.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 DESJARDINS, JEFF. "The History of Tungsten, the Strongest Natural Metal on Earth". visualcapitalist.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Facts About Tungsten". livescience.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ede, Andrew. The Chemical Element: A Historical Perspective.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "HISTORY OF TUNGSTEN". itia.info. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "tungsten mine". debouchage-wiame.be. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "History". vitalmetals.com.au. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 "Tungsten processing". britannica.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Hard Facts about Tungsten". mi-techmetals.com. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ History of Chemistry.

- ↑ DK. 1000 Inventions and Discoveries.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Rollinson, Carl L. The Chemistry of Chromium, Molybdenum and Tungsten: Pergamon International Library of Science, Technology, Engineering and Social Studies.

- ↑ Percy, John. Metallurgy: The Art of Extracting Metals from Their Ores, and Adapting Them to Various Purposes of Manufacture, Volume 2.

- ↑ Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior ..., Volume 4, Part 3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Incandescent lamp with ductile tungsten filament". americanhistory.si.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Boorstin, Daniel J. The Americans: The Democratic Experience.

- ↑ Heerding, A. The History of N. V. Philips' Gloeilampenfabrieken: Volume 2, A Company of Many Parts.

- ↑ "Coolidge, William David (1873-1975)". harvardsquarelibrary.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Transition Elements: Advances in Research and Application: 2011 Edition.

- ↑ Materials Survey: Tungsten. United States. Business and Defense Services Administration.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lassner, Erik; Schubert, Wolf-Dieter. Tungsten: Properties, Chemistry, Technology of the Element, Alloys, and Chemical Compounds.

- ↑ "Tungsten : proceedings of the First International Tungsten Symposium, Stockholm, September 5-7, 1979 / edited ... by Mining Journal Books Limited in co-operation with the Primary Tungsten Association and the Consumer Reporting Group, co-sponsors of the symposium.". trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "International Tungsten Symposium". classify.oclc.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ "International Tungsten Symposium (1st :, 1979 : Stockholm, Sweden)". catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Werner, Antony B. T.; Sinclair, W. D.; Amey, Earle B. International Strategic Mineral Issues Summary Report--tungsten.

- ↑ China Mining Laws and Regulations Handbook. International Business Publications, USA.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of the Tungsten Filament Lightbulb". mmta.co.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ "Tungsten". Google Trends. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ "Tungsten". books.google.com. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ "Tungsten". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 27 April 2021.