Difference between revisions of "Timeline of psychoactive drugs"

From Timelines

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

| 1969 || Synthesis || {{w|Bupropion}}, used as {{w|antidepressant}} and for {{w|smoking cessation}}, is first synthesized.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Stolberg|first1=Victor B.|title=ADHD Medications: History, Science, and Issues|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=5IE5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA74&dq=%22bupropion%22+%221969%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiTheWnhuDZAhWHhZAKHeeGDOYQ6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=%22bupropion%22%20%221969%22&f=false}}</ref> || | | 1969 || Synthesis || {{w|Bupropion}}, used as {{w|antidepressant}} and for {{w|smoking cessation}}, is first synthesized.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Stolberg|first1=Victor B.|title=ADHD Medications: History, Science, and Issues|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=5IE5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA74&dq=%22bupropion%22+%221969%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiTheWnhuDZAhWHhZAKHeeGDOYQ6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=%22bupropion%22%20%221969%22&f=false}}</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1976 || Synthesis || {{w|Modafinil}}, used for disorders such as {{w|narcolepsy}}, {{w|shift work sleep disorder}}, {{w|idiopathic hypersomnia}}, and {{w|excessive daytime sleepiness}} is first synthesized.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Triggle|first1=David J.|last2=Taylor|first2=John B.|title=Comprehensive medicinal chemistry II: editors-in-chief, John B. Taylor, David J. Triggle|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=IIUvAQAAIAAJ&q=%22modafinil%22+%22in+1950..1980%22&dq=%22modafinil%22+%22in+1950..1980%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj4oqKQiuHZAhUChpAKHSvhBHMQ6AEIJzAA}}</ref> || {{w|France}} | + | | 1976 || Synthesis || {{w|Modafinil}}, used for disorders such as {{w|narcolepsy}}, {{w|shift work sleep disorder}}, {{w|idiopathic hypersomnia}}, and {{w|excessive daytime sleepiness}}, is first synthesized.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Triggle|first1=David J.|last2=Taylor|first2=John B.|title=Comprehensive medicinal chemistry II: editors-in-chief, John B. Taylor, David J. Triggle|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=IIUvAQAAIAAJ&q=%22modafinil%22+%22in+1950..1980%22&dq=%22modafinil%22+%22in+1950..1980%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj4oqKQiuHZAhUChpAKHSvhBHMQ6AEIJzAA}}</ref> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1985 || Introduction || Scientists at {{w|AstraZeneca}} Pharmaceuticals develop {{w|quetiapine}}.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Riedel|first1=Michael|last2=Müller|first2=Norbert|last3=Strassnig|first3=Martin|last4=Spellmann|first4=Ilja|last5=Severus|first5=Emanuel|last6=Möller|first6=Hans-Jürgen|title=Quetiapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654633/|pmc=2654633}}</ref> || | | 1985 || Introduction || Scientists at {{w|AstraZeneca}} Pharmaceuticals develop {{w|quetiapine}}.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Riedel|first1=Michael|last2=Müller|first2=Norbert|last3=Strassnig|first3=Martin|last4=Spellmann|first4=Ilja|last5=Severus|first5=Emanuel|last6=Möller|first6=Hans-Jürgen|title=Quetiapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654633/|pmc=2654633}}</ref> || | ||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 20, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! psychoactive | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1950 || 6 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1955 || 1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960 || 24 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1965 || 119 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || 358 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1975 || 940 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 1,060 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || 1,430 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 2,440 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || 3,120 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 4,520 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2005 || 6,660 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 9,220 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015 || 15,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 19,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Psychoactive drugs gscho.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Trends === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Psychoactive drug, from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Psychoactive drug |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F0m1vx |website=Google Trends |access-date=13 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Psychoactive drug gt.png|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Psychoactive drug, from 1940 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Psychoactive drug |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Psychoactive+drug&year_start=1940&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&case_insensitive=true |website=books.google.com |access-date=13 April 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Psychoactive drug ngram.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Psychoactive drug}}, from July 2015 to March 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Psychoactive drug |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Psychoactive+drug&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=13 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Psychoactive drug wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

==Meta information on the timeline== | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:02, 8 April 2024

This is a timeline of psychoactive drugs, focusing on their medical use in anesthesia, pain management, and mental disorders.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Ancient times | The use of natural extracts for medicinal purposes goes back thousands of years.[1] Most likely discovered through a combination of trial and error, early medicines often had as much religious and spiritual significance as they did healing importance. Plants were the basis of the ancient medicines, and were complemented with minerals and animal substances. Often the same plants and herbs were used for similar diseases among different civilizations, even though they were discovered separately.[2] |

| 5th–15th century | During the Middle Ages, opium continues to be used and abused in several societies.[3] However, treatment of disease through development of new herbal remedies may have been very difficult in an environment where the prevailing attitude is that disease is God’s punishment for sin. Practitioners of herbal remedies would often be seen as heretics. Medical progress is very weak due to the prevailing unscientific opinion.[2] Nightshade varietals are sometimes used by medicine men and women who would be later accused of witchcraft. Drugs include datura, henbane, belladonna, and the mandrake root.[4] |

| 14th–17th century | During the Renaissance, the development of medicinal remedies in Europe is reborn. In the 15th century, Italian anatomists use opium to sedate prisoners before performing dissections on them.[3] Paracelsus brings opium into the European pharmacopoeia in the early 16th century, and also develops the modern concept of dose dependency for drug action and toxicity.[2] |

| 18th century | In sharp contrast to ancient times, in the 18th century, while only a few substances survive and retain the cultural uses (like some tribes in Australia, the Amazon rainforest, etc.), many substances sift to a non–socially accepted pattern of abuse and dependence. Addiction becomes a global public health problem. China recognizes opiums addictive potential, alcoholism appears in European working class, psychiatry matures into a scientific discipline, and influential physicians write about compulsive drinking.[5] |

| 19th century | There are no legal restraints on the use of opiates in either country throughout the century.[4] During the mid to late century, many manufacturers proudly proclaim that their products contain cocaine or opium.[6] However, addiction is a main focus of research. The first medical journals of addiction appear.[5] |

| 20th century | Like many consumer items, in the 20th century psychoactive drugs become globalized, commoditized, mass produced, marketed, regulated, licensed, and consumed in variety and numbers higher than any other time in history.[7] At the turn of the century, hundreds of patent medications are available, many loaded with opium, morphine, cocaine, Cannabis, and alcohol.[4] Throughout the years, the rapid increase in knowledge sees the formation of a disease concept of addiction which includes the psychosocial and neurolobiological foundations and consequences of addiction.[7] Diagnostic classifications, neurobiological and genetic research, and classification of drugs into stimulants, inebriants, hallucinogens, euphoriants and hypnotics merge.[5] |

| 21th century | Technological advances apply to a broad research in psychoactive drugs. Genomics, pharmacogenomics, neuroimaging, molecular neurobiology, and neurogenetics merge.[5] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50,000 years ago | Neanderthal burial site in Iraq is found to contain remains of the herbal stimulant ephedra. Palaeolithic cave art across Europe and Africa suggests artists had experience of hallucinogens (or possibly migraines).[8] | Iraq | |

| c.14,000 BC–c.12,000 BC | Remnants of ancient poppy plantations in Spain, Greece, Northeast Africa, Egypt, and Mesopotamia are evidence of the widespread early use of opium.[4] | Spain, Greece, Northeast Africa, Middle East | |

| c.10,000 BC | Earliest agriculture. Some evidence that the first crops include psychoactive plants such as mandrake, tobacco, coffee and cannabis.[8] | ||

| c.9000 BC | Evidence of the use of rice wine emerges in China.[4] | China | |

| c.7000 BC | Betel seeds, chewed for their stimulant effects, are found in archaeological sites in Asia.[8][9] | ||

| c.6000 BC | Production | Tobacco is cultivated and used by native South Americans.[9][8] | |

| c.5000 BC | Production | The Sumerians already make use of opium.[10] | |

| c.4200 BC | Opium poppy seed pods (papaver somniferum) are found in a burial site at Albuñol, Spain.[8][9] | Spain | |

| c.4000 BC | Production | Wine and beer are produced in Egypt and Sumeria.[8] | Egypt, Near East, Middle East |

| c.3500 BC | The description of a brewery in an Egyptian papyrus is the earliest historical record of the production of alcohol.[10] | Egypt | |

| c.3000 BC | Introduction | The use of tea in China originates around this time.[10] | China |

| c.3000 BC | Production | Cannabis is cultivated in China and other regions of Asia; evidence of cannabis smoking is also found in eastern Europe.[10][9] | |

| c.2500 BC | Early historical evidence of the eating of poppy seeds among the Lake Dwellers on Switzerland.[10] | Switzerland | |

| c.2000 BC | Coca residues are found in the hair of Andean mummies.[8][9] | ||

| c.1000 BC | Central Americans erect temples to mushroom gods.[9] | ||

| 800 BC | Introduction | Distilled spirits and rice beer originate in India.[8][11][12] | India |

| 1275 | Discovery | Ether is discovered.[4] | |

| 1493 | Introduction | Columbus and his crew introduce tobacco in Europe.[10] | Europe |

| c.1500 | Introduction | Opium smoking is first introduced to China.[4] | China |

| c.1525 | Introduction | Swiss physician Paracelsus introduces laudanum, or tincture of opium, into the practice of medicine.[13][10] | Switzerland |

| 1551 | Publication | English physician William Turner advocates the use of the opium poppy in his herbal treatise, the first one to be published in the English language. | United Kingdom |

| 1625–1665 | Introduction | In response to outbreaks of plague in London, mithridatium, based on a complex formulation including opium, is one of the main recommended remedies.[3] | United Kingdom |

| 1750–1799 | Introduction | English botanist William Withering introduces the digitalis, an extract from the plant foxglove, for treatment of cardiac problems.[14] | United Kingdom |

| 1753 | Publication | Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus publishes his Species Plantarum, which first classifies the opium poppy as Papaver Somniferum, which literally means "sleep–inducing".[3] | Sweden |

| 1760s | Introduction | English physician Thomas Sydenham popularizes laudanum.[15] | United Kingdom |

| 1762 | Introduction | English physician Thomas Dover introduces his prescription for a diaphoretic powder, which he recommends mainly for the treatment of gout. Soon named “Dover’s powder”, this compound becomes the most widely used opium preparation during the next 150 years.[10][3] | United Kingdom |

| 1776 | Discovery | English chemist Joseph Priestley discovers nitrous oxide (laughing gas).[4] | United Kingdom |

| 1804–1806 | Introduction | German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner manages to extract morphine from opium, launching the first generation of true drugs.[2][10][4] | Germany |

| 1821 | Isolation | German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge extracts caffeine from coffee beans for the first time.[16] | Germany |

| 1828 | Isolation | Nicotine is first isolated from the tobacco plant by physician Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and chemist Karl Ludwig Reimann of Germany, who consider it a poison.[17][18] | |

| 1831 | Discovery | Chloroform is discovered.[4] | |

| 1840s | Introduction | Lithium is first used to treat bladder stones and gout.[19] | |

| 1841 | Treatment | French psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau uses hashish in treatment of mental patients at the Bicêtre Hospital.[10][20][21][22] | France |

| 1841 | Discovery | Russian chemist Alexander Voskresensky first discovers theobromine.[23] | |

| 1842 | Scientific development | French physiologist Claude Bernard discovers that the arrow poison curare acts at the neuromuscular junction to interrupt the stimulation of muscle by nerve impulses.[24] | |

| 1844 | Isolation | Cocaine is isolated in its pure form from the leaf of the coca plant.[10][25] | |

| 1850s | Treatment | Opiates are injected to treate neuralgia.[3] | |

| 1864 | Synthesis | Adolf von Baeyer in Ghent synthesizes barbituric acid, the first barbiturate.[10] | Belgium |

| 1869 | Discovery | The first synthetic drug, chloral hydrate, is discovered and introduced as a sedative-hypnotic.[26] | |

| 1869 | Treatment | English physician Clifford Allbutt recommends the injection of morphine to treat heart disease.[3][27] | United Kingdom |

| 1875 | Treatment | Dr. Anderson recommends the injection of morphine to treat asthma.[3] | |

| 1880 | Isolation | Hyoscine is isolated. The drug would later be extensively used in psychiatry.[28] | |

| 1884 | Introduction | Cocaine is first introduced as a local anesthetic.[19] | |

| 1886 | Patent | The recipe for Coca-Cola is patented, including coca leaves and caffeine-rich kola nuts. in 1906 Coca leaves would be removed from the recipe for Coca-Cola.[8] | United States |

| 1887 | Synthesis | Amphetamine is synthesized in Germany.[4][8] | Germany |

| 1893 | Synthesis | Methamphetamine is first synthesized from ephedrine.[29] | Japan |

| 1898 | Synthesis | Diacetylmorphine (heroin) is synthesized in Germany.[10] | Germany |

| 1905 | Discovery | German chemist Alfred Einhorn discovers the injectable local anesthetic procaine, which would become Novocain.[19] | |

| 1912 | Synthesis | 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is synthesised by pharmaceutical firm Merck.[8] | |

| 1912 | Introduction | Phenobarbital is introduced into therapeutics under the trade name of Luminal.[10] | |

| 1938 | Isolation | Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), the active ingredient in ergot fungus, is isolated and extracted by Swiss scientist Albert Hoffman and is considered as a potential treatment for mental illness.[4] | |

| 1954 | Introduction | Benztropine is commercially introduced.[30] | |

| 1958 | Discovery | Denatonium is discovered during research on local anesthetics by MacFarlan Smith of Edinburgh, Scotland, and registered under the trademark Bitrex.[31] | United Kingdom |

| 1964 | Synthesis | Romanian chemist Corneliu E. Giurgea synthesizes nootropic piracetam, a compound shown to boost memory, learning, creativity, verbal fluency, and brain circulation.[32] | |

| 1968 | Synthesis | Memantine, used to treat moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease, is first synthesized.[33] | |

| 1969 | Synthesis | Bupropion, used as antidepressant and for smoking cessation, is first synthesized.[34] | |

| 1976 | Synthesis | Modafinil, used for disorders such as narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder, idiopathic hypersomnia, and excessive daytime sleepiness, is first synthesized.[35] | France |

| 1985 | Introduction | Scientists at AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals develop quetiapine.[36] | |

| 1997 | Introduction | Dopamine agonist pramipexole is released in the United States.[37] | United States |

| 1997 | Introduction | Dopamine agonist ropinirole is approved for medical use.[38] |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 20, 2021.

| Year | psychoactive |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 6 |

| 1955 | 1 |

| 1960 | 24 |

| 1965 | 119 |

| 1970 | 358 |

| 1975 | 940 |

| 1980 | 1,060 |

| 1985 | 1,430 |

| 1990 | 2,440 |

| 1995 | 3,120 |

| 2000 | 4,520 |

| 2005 | 6,660 |

| 2010 | 9,220 |

| 2015 | 15,600 |

| 2020 | 19,800 |

Google Trends

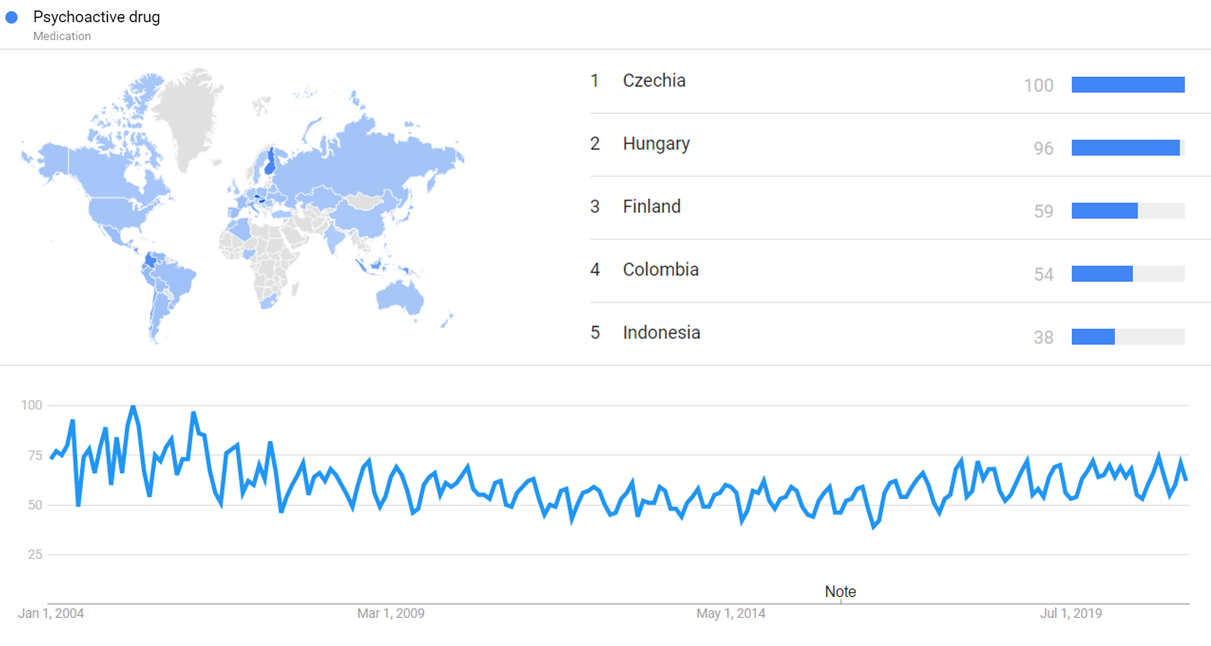

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Psychoactive drug, from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[39]

Google Ngram Viewer

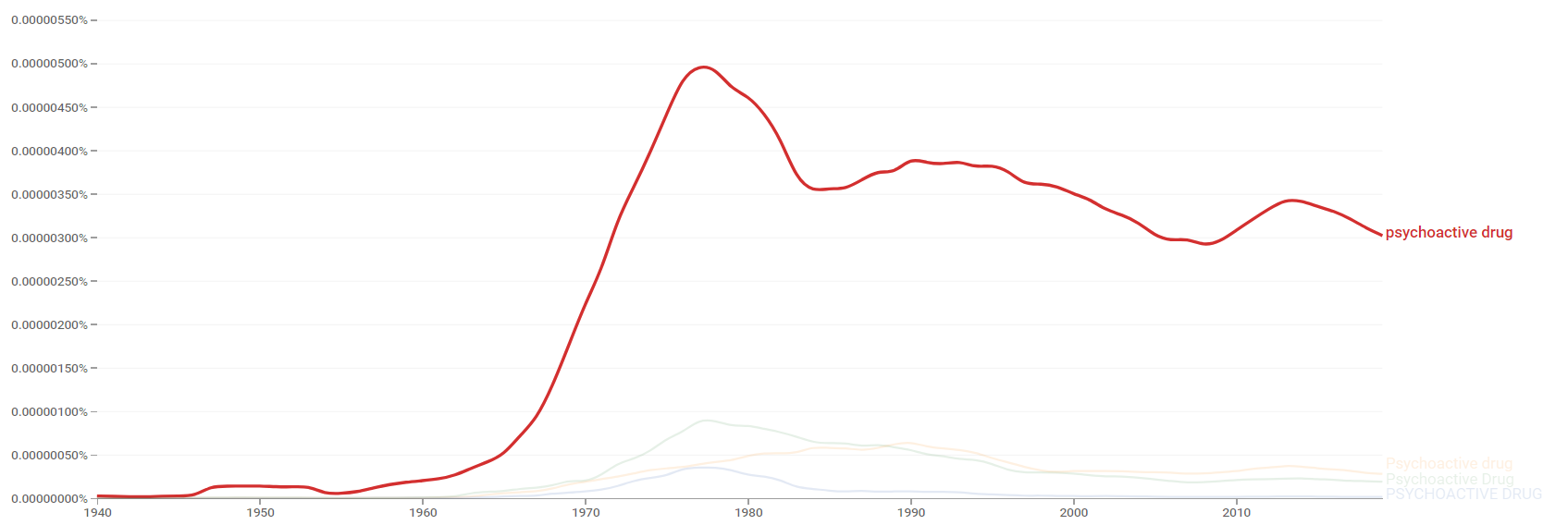

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Psychoactive drug, from 1940 to 2019.[40]

Wikipedia Views

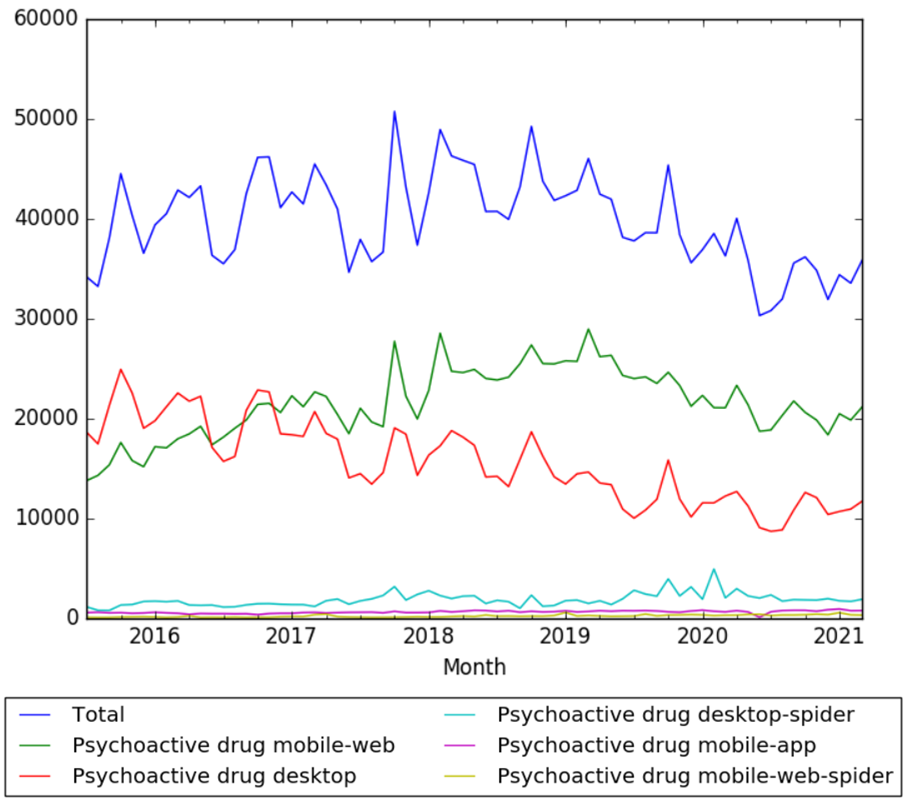

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Psychoactive drug, from July 2015 to March 2021.[41]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "A SHORT HISTORY OF DRUG DISCOVERY". pharmsci.uci.edu. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "The History of Therapeutic Drug Development". twistbioscience.com. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Stolberg, Victor B. Painkillers: History, Science, and Issues.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 "– PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS: CLASSIFICATION AND HISTORY" (PDF). cnsproductions.com. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 On Human Nature: Biology, Psychology, Ethics, Politics, and Religion (Michel Tibayrenc, Francisco J. Ayala ed.).

- ↑ "Psychoactive drugs before prohibition". boingboing.net. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "20th Century: The Pendulum of Use, Abuse, Regulation and Subsitution". evolutionofdruguse.wordpress.com. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 "Timeline: Drugs and Alcohol". newscientist.com. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Plant, Martin. Drug Nation: Patterns, Problems, Panics & Policies.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 "Timeline of Events in the History of Drugs". inpud.wordpress.com. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Maiya, Harish. The King of Good Times.

- ↑ Dasgupta, Amitava; Langman, Loralie J. Pharmacogenomics of Alcohol and Drugs of Abuse.

- ↑ Deming, David. Science and Technology in World History, Volume 3: The Black Death, the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution.

- ↑ "HISTORY OF DRUG DISCOVERY AND DEVELOPMENT". onlinelibrary.wiley.com. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Kamieński, Łukasz. Shooting Up: A Short History of Drugs and War.

- ↑ Hayes, Dayle; Laudan, Rachel. Food and Nutrition/Editorial Advisers, Dayle Hayes, Rachel Laudan.

- ↑ "Medicinal uses of tobacco in history". PMC 1079499

. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Magazin für Pharmacie, Volume 6; Volumes 23-24.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 GELMAN, LAUREN. "The Accidental History of 10 Common Drugs". rd.com. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Emboden, William A. Narcotic plants.

- ↑ Booth, Martin. Cannabis: A History.

- ↑ Boon, Marcus. The Road of Excess: A History of Writers on Drugs.

- ↑ von Bibra,, Baron Ernst; Ott, Jonathan. Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants.

- ↑ "A brief history of pharmacology". pubs.acs.org. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Ciment, James. Social Issues in America: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Jones, AW. "Early drug discovery and the rise of pharmaceutical chemistry". PMID 21698778. doi:10.1002/dta.301.

- ↑ Padwa, Howard. Social Poison: The Culture and Politics of Opiate Control in Britain and France, 1821--1926.

- ↑ A history of psychiatry: from the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac.

- ↑ Haight, Wendy; Ostler, Teresa; Black, James; Kingery, Linda. Children of Methamphetamine-Involved Families: The Case of Rural Illinois.

- ↑ Krantz, John Christian; Carr, Charles Jelleff; Aviado, Domingo M. Krantz and Carr's Pharmacologic principles of medical practice: a textbook on pharmacology and therapeutics for students and practitioners of medicine, pharmacy, and dentistry.

- ↑ "DENATONIUM". edinformatics.com. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ "Dr. Corneliu E. Giurgea – The Father of Nootropics". noomind.org. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Lertxundi, Unax; Medrano, Juan; Hernández, Rafael. Psychopharmacological Issues in Geriatrics.

- ↑ Stolberg, Victor B. ADHD Medications: History, Science, and Issues.

- ↑ Triggle, David J.; Taylor, John B. Comprehensive medicinal chemistry II: editors-in-chief, John B. Taylor, David J. Triggle.

- ↑ Riedel, Michael; Müller, Norbert; Strassnig, Martin; Spellmann, Ilja; Severus, Emanuel; Möller, Hans-Jürgen. "Quetiapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders". PMC 2654633

.

.

- ↑ Cozza, Kelly L.; Armstrong, Scott C.; Oesterheld, Jessica R. Concise Guide to Drug Interaction Principles for Medical Practice: Cytochrome P450s, UGTs, P-glycoproteins.

- ↑ Jankovic, Joseph; Tolosa, Eduardo. Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders.

- ↑ "Psychoactive drug". Google Trends. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ "Psychoactive drug". books.google.com. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ "Psychoactive drug". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 13 April 2021.