Difference between revisions of "Timeline of cognitive behavioral therapy"

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This is a '''timeline of {{w|cognitive behavioral therapy}}'''. CBT has been shown to be effective in over 350 outcome studies for myriad psychiatric disorders.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bieling |first1=Peter J. |last2=McCabe |first2=Randi E. |last3=Antony |first3=Martin M. |title=Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Groups |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=9RImQCQx_ZsC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=%22Cognitive+behavioral+therapy%22+%22in+1970..1979%22&source=bl&ots=fPBm7_iRA2&sig=ACfU3U2_iAk7HJrZyIWGrTcoNwJl8uWChg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjNwKKAw4LhAhV2JrkGHaWyBqMQ6AEwAnoECAQQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Cognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%22%20%22in%201970..1979%22&f=false}}</ref> | + | This is a '''timeline of {{w|cognitive behavioral therapy}}''', a psychotherapeutic approach that focuses on the connection between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. It aims to help individuals identify and modify negative or distorted patterns of thinking and behavior that contribute to emotional distress or problematic behaviors. CBT has been shown to be effective in over 350 outcome studies for myriad psychiatric disorders.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bieling |first1=Peter J. |last2=McCabe |first2=Randi E. |last3=Antony |first3=Martin M. |title=Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Groups |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=9RImQCQx_ZsC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=%22Cognitive+behavioral+therapy%22+%22in+1970..1979%22&source=bl&ots=fPBm7_iRA2&sig=ACfU3U2_iAk7HJrZyIWGrTcoNwJl8uWChg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjNwKKAw4LhAhV2JrkGHaWyBqMQ6AEwAnoECAQQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Cognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%22%20%22in%201970..1979%22&f=false}}</ref> |

==Big picture== | ==Big picture== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Full timeline== | ==Full timeline== | ||

| Line 24: | Line 19: | ||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Location | ! Year !! Event type !! Details !! Location | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 50AD || Notable birth || {{w|Epictetus}} is born. One of the most prominent stoics, he would hold the belief that logic could be utilized to recognize and discard false beliefs that give rise to harmful emotions. This perspective would have a significant impact on modern cognitive-behavioral therapy by shaping how therapists identify cognitive distortions that contribute to feelings of depression and anxiety. As a result, various ancient philosophical traditions, particularly {{w|Stoicism}}, are identified as precursors to certain fundamental aspects of CBT.<ref>{{Cite book |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=XsOFyJaR5vEC&pg=PR19|title = The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy|author = Donald Robertson|page = xix|year = 2010|publisher = Karnac|location = London|isbn = 978-1855757561}}</ref><ref name=Mathews>{{cite web |url=http://www.vacounseling.com/stoicism-cbt/ |title=Stoicism and CBT: Is Therapy A Philosophical Pursuit? | vauthors = Mathews J |publisher=Virginia Counseling |date=2015 |website=Virginia Counseling}}</ref> || {{w|Ancient Greece}} ({{w|Hierapolis}}) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1897 || Scientific development || Russian physiologist {{w|Ivan Pavlov}} describes the principles of the conditioned reflex, which, unlike an innate reflex, is only acquired after a period of cerebral learning.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Vincent |first1=Jean-Didier |last2=Lledo |first2=Pierre-Marie |title=The Custom-Made Brain: Cerebral Plasticity, Regeneration, and Enhancement |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=L8bbAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA163&dq=%22in+1897%22+%22ivan+pavlov%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZzvTV_JPhAhWEHrkGHRT-DzwQ6AEIOjAD#v=onepage&q=%22in%201897%22%20%22ivan%20pavlov%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=A Study Guide for Psychologists and Their Theories for Students: IVAN PAVLOV |publisher=Gale |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ER4eCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT10&dq=%22in+1897%22+%22ivan+pavlov%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZzvTV_JPhAhWEHrkGHRT-DzwQ6AEINTAC#v=onepage&q=%22in%201897%22%20%22ivan%20pavlov%22&f=false}}</ref> || | | 1897 || Scientific development || Russian physiologist {{w|Ivan Pavlov}} describes the principles of the conditioned reflex, which, unlike an innate reflex, is only acquired after a period of cerebral learning.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Vincent |first1=Jean-Didier |last2=Lledo |first2=Pierre-Marie |title=The Custom-Made Brain: Cerebral Plasticity, Regeneration, and Enhancement |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=L8bbAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA163&dq=%22in+1897%22+%22ivan+pavlov%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZzvTV_JPhAhWEHrkGHRT-DzwQ6AEIOjAD#v=onepage&q=%22in%201897%22%20%22ivan%20pavlov%22&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=A Study Guide for Psychologists and Their Theories for Students: IVAN PAVLOV |publisher=Gale |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=ER4eCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT10&dq=%22in+1897%22+%22ivan+pavlov%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZzvTV_JPhAhWEHrkGHRT-DzwQ6AEINTAC#v=onepage&q=%22in%201897%22%20%22ivan%20pavlov%22&f=false}}</ref> || | ||

| Line 103: | Line 100: | ||

| Late 1990s || Therapy development || {{w|Inference-based therapy}} is developed as a form of {{w|cognitive therapy}} for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder.<ref>O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1995). Inference processes in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Some clinical observations. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 887-96.</ref><ref>O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1999). A cognitive approach to the treatment of primary inferences in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13, 359-75.</ref> || | | Late 1990s || Therapy development || {{w|Inference-based therapy}} is developed as a form of {{w|cognitive therapy}} for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder.<ref>O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1995). Inference processes in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Some clinical observations. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 887-96.</ref><ref>O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1999). A cognitive approach to the treatment of primary inferences in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13, 359-75.</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2000 || Scientific development || CBT | + | | 2000 || Scientific development || A study compares the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and {{w|interpersonal psychotherapy}} (IPT) in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. It involves 220 women with bulimia nervosa and followed them for 1 year. The results show that CBT was more effective than IPT in achieving recovery and remission from bulimia nervosa in the short term. However, at the 1-year follow-up, the outcomes of CBT and IPT were similar. The study concludes that while both therapies were effective, IPT took longer to produce clinical change compared to CBT.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Stewart Agras |first1=W. |last2=Walsh |first2=B. Timothy |last3=Fairburn |first3=Christopher G. |title=A Multicenter Comparison of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Bulimia Nervosa |doi=10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459 |url=https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/481603}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 2000 || Scientific development || The {{w|American Psychiatric Association}} Practice Guidelines indicate that, among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy and {{w|interpersonal psychotherapy}} have the best-documented efficacy for treatment of {{w|major depressive disorder}}.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hirschfeld |first=Robert M.A. |chapter = Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2nd Edition|year = 2006|isbn = 978-0-89042-336-3|volume = 1|title=APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Comprehensive Guidelines and Guideline Watches|chapter-url=http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar-watch.pdf |chapter-format=PDF}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | | 2000 || Scientific development || The {{w|American Psychiatric Association}} Practice Guidelines indicate that, among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy and {{w|interpersonal psychotherapy}} have the best-documented efficacy for treatment of {{w|major depressive disorder}}.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hirschfeld |first=Robert M.A. |chapter = Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2nd Edition|year = 2006|isbn = 978-0-89042-336-3|volume = 1|title=APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Comprehensive Guidelines and Guideline Watches|chapter-url=http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar-watch.pdf |chapter-format=PDF}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

| Line 114: | Line 111: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2005 || Scientific development || Study finds evidence that CBT is a particularly promising adjunct to {{w|pharmacotherapy}} for {{w|schizophrenia}} patients who suffer from an acute episode of {{w|psychosis}} rather than a more chronic condition.<ref name="The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses"/> || | | 2005 || Scientific development || Study finds evidence that CBT is a particularly promising adjunct to {{w|pharmacotherapy}} for {{w|schizophrenia}} patients who suffer from an acute episode of {{w|psychosis}} rather than a more chronic condition.<ref name="The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses"/> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || Recommendation || The British {{w|National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence}} (NICE) updates its recommendations on cognitive behavior therapy in the {{w|National Health Service}}, recommending two computerized CBT packages for managing depression and phobia based on new evidence. Computerized CBT provides treatment through interactive computer interfaces. NICE recognizes the preference for face-to-face therapy, but limited availability hinders access. Computerized packages are considered safe and deliver similar guidance. However, it is stated that they may not be suitable for severe depression. NICE selected two packages based on their effectiveness and cost after reviewing five options.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mayor |first1=Susan |title=NICE advocates computerised CBT |journal=BMJ |date=4 March 2006 |volume=332 |issue=7540 |pages=504.3 |doi=10.1136/bmj.332.7540.504-b}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2008 || Literature || Rhena Branch and Rob Willson publish ''Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books/about/Cognitive_Behavioural_Therapy_Workbook_F.html?id=lNe4V6OpXu8C&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y |website=books.google.com |accessdate=21 March 2019}}</ref> || | | 2008 || Literature || Rhena Branch and Rob Willson publish ''Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books/about/Cognitive_Behavioural_Therapy_Workbook_F.html?id=lNe4V6OpXu8C&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y |website=books.google.com |accessdate=21 March 2019}}</ref> || | ||

| Line 134: | Line 133: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

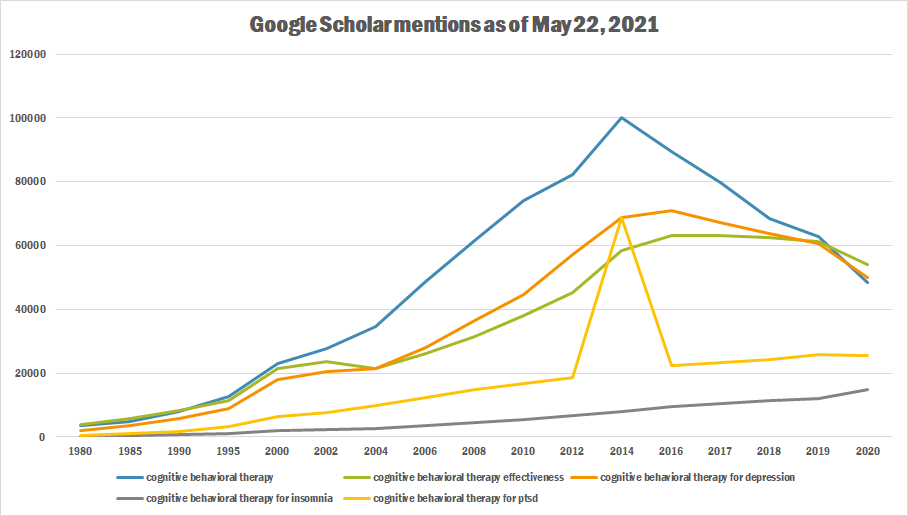

| + | === Mentions on Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 22, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! cognitive behavioral therapy | ||

| + | ! cognitive behavioral therapy effectiveness | ||

| + | ! cognitive behavioral therapy for depression | ||

| + | ! cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia | ||

| + | ! cognitive behavioral therapy for ptsd | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 3,410 || 3,910 || 1,920 || 229 || 451 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || 4,880 || 5,660 || 3,580 || 417 || 1,020 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 7,920 || 8,140 || 5,810 || 602 || 1,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || 12,500 || 11,400 || 8,930 || 917 || 3,340 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 23,000 || 21,500 || 18,000 || 1,950 || 6,460 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2002 || 27,700 || 23,500 || 20,400 || 2,390 || 7,790 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004 || 34,500 || 21,300 || 21,500 || 2,770 || 9,810 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || 48,700 || 26,000 || 27,900 || 3,450 || 12,200 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || 61,500 || 31,400 || 36,500 || 4,440 || 14,700 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 74,100 || 38,000 || 44,500 || 5,320 || 16,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || 82,100 || 45,300 || 57,100 || 6,810 || 18,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2014 || 100,000 || 58,400 || 68,900 || 7,990 || 68,700 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2016 || 89,400 || 63,200 || 71,000 || 9,490 || 22,400 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017 || 79,700 || 63,100 || 67,300 || 10,300 || 23,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || 68,400 || 62,400 || 63,700 || 11,300 || 24,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2019 || 62,800 || 61,100 || 60,700 || 12,100 || 25,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 48,300 || 53,900 || 50,000 || 14,800 || 25,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Cognitive tb.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Trends === | ||

| + | |||

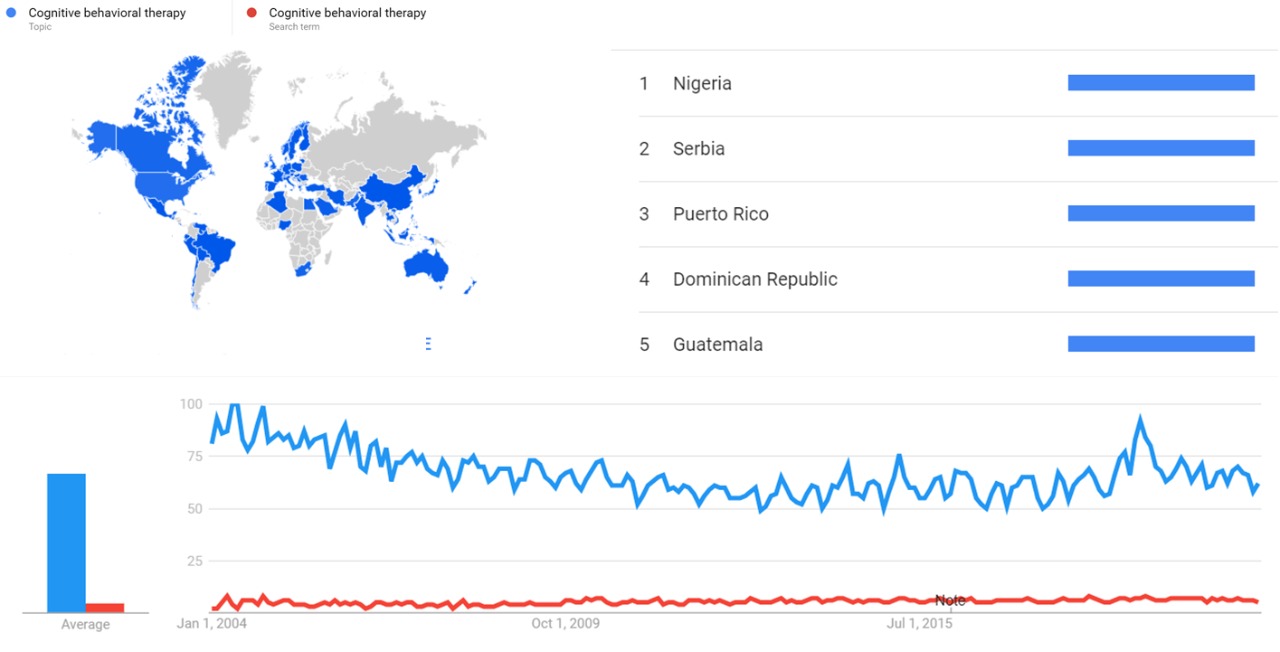

| + | The comparative chart below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Cognitive behavioral therapy (Topic and Search term) from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.<ref>{{cite web |title=Cognitive behavioral therapy |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F025tlrr,Cognitive%20behavioral%20therapy |website=trends.google.com |access-date=15 January 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Cognitive behavioral therapy gtrends.jpeg|thumb|center|800px]] | ||

| + | |||

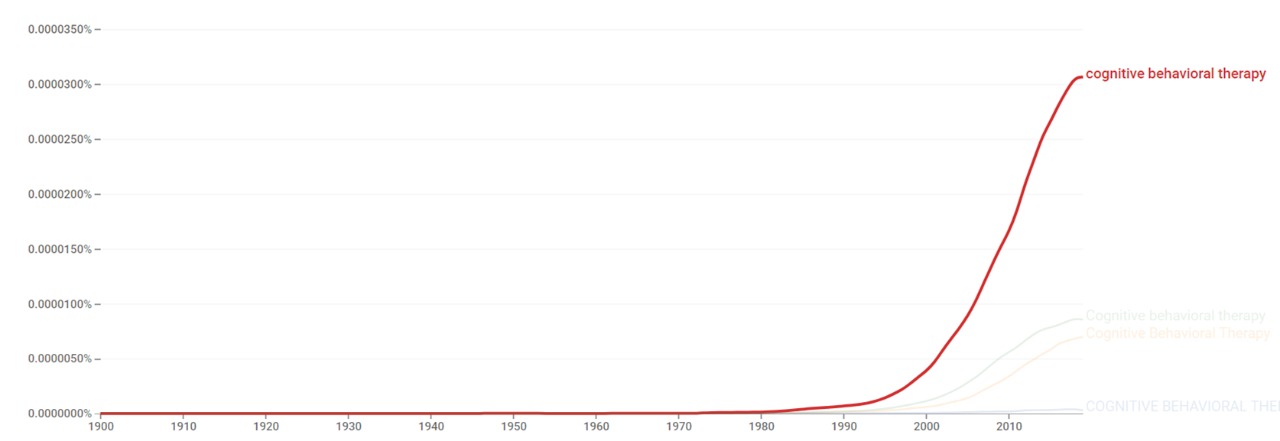

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Cognitive behavioral therapy from 1900 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Cognitive behavioral therapy |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Cognitive+behavioral+therapy&year_start=1900&year_end=2019&case_insensitive=on&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t4%3B%2CCognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Bcognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BCognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BCognitive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BCOGNITIVE%20BEHAVIORAL%20THERAPY%3B%2Cc0#t4%3B%2CCognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Bcognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc1%3B%3BCognitive%20behavioral%20therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BCognitive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BCOGNITIVE%20BEHAVIORAL%20THERAPY%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=15 January 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Cognitive behavioral therapy ngram.jpeg|thumb|center|800px]] | ||

| + | |||

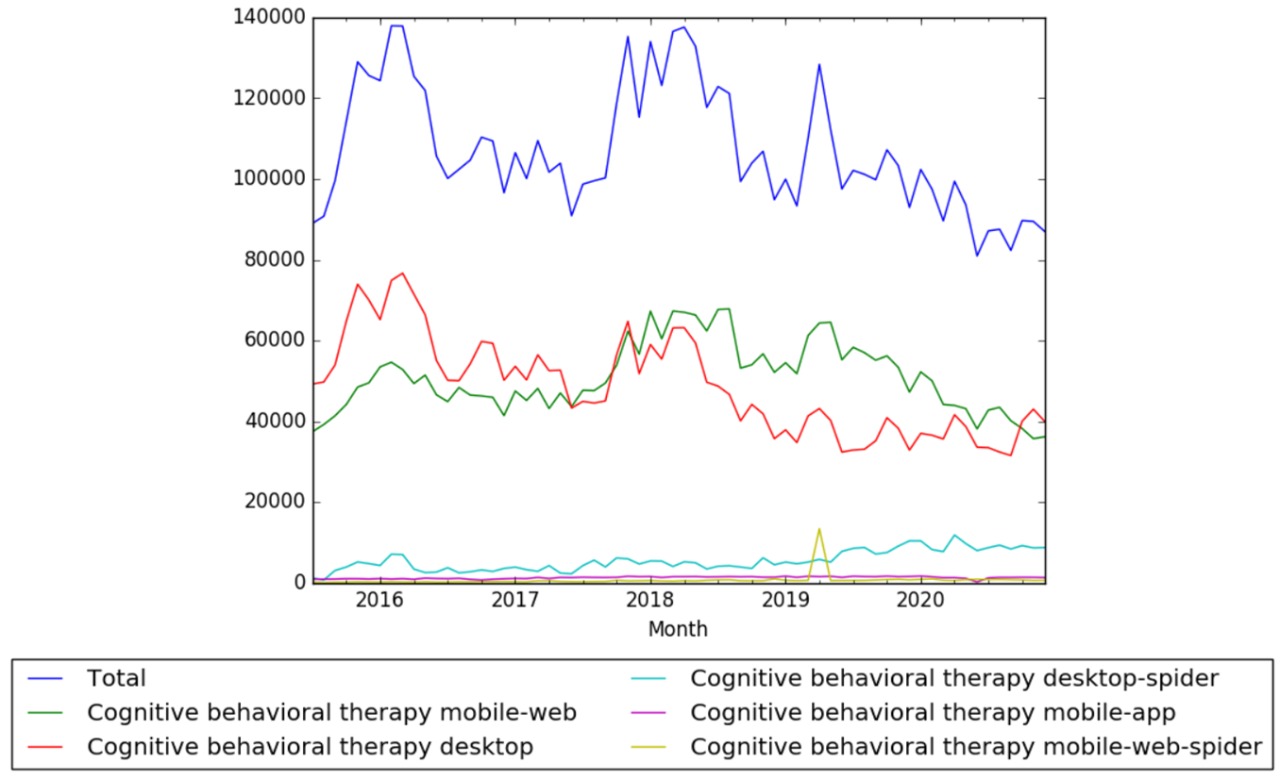

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Cognitive behavioral therapy}} on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to December 2020. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Cognitive behavioral therapy wv.jpeg|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

==Meta information on the timeline== | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

| Line 152: | Line 221: | ||

* Sample questions section | * Sample questions section | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* {{w|List of cognitive–behavioral therapies}} | * {{w|List of cognitive–behavioral therapies}} | ||

* {{w|Category:Cognitive behavioral therapy}} | * {{w|Category:Cognitive behavioral therapy}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:15, 9 June 2023

This is a timeline of cognitive behavioral therapy, a psychotherapeutic approach that focuses on the connection between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. It aims to help individuals identify and modify negative or distorted patterns of thinking and behavior that contribute to emotional distress or problematic behaviors. CBT has been shown to be effective in over 350 outcome studies for myriad psychiatric disorders.[1]

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1950s–1960s | Behavioral therapy becomes widely utilized by researchers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa, who are inspired by the behaviorist learning theory of Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and Clark L. Hull.[2] |

| 1960s | CBT is first developed by American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, who formulates the idea for the therapy after noticing that many of his patients have internal dialogues that were almost a form of them talking to themselves. He also observes that his patients’ thoughts often impact their feelings, and he calls these emotionally-loaded thoughts “automatic thoughts.” Martin also explains that Beck originally names CBT “cognitive therapy,” because it focuses on each patient’s thought process.[3] |

| 1970s–1980s | An increasing interest in CBT takes place in the period.[4] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50AD | Notable birth | Epictetus is born. One of the most prominent stoics, he would hold the belief that logic could be utilized to recognize and discard false beliefs that give rise to harmful emotions. This perspective would have a significant impact on modern cognitive-behavioral therapy by shaping how therapists identify cognitive distortions that contribute to feelings of depression and anxiety. As a result, various ancient philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism, are identified as precursors to certain fundamental aspects of CBT.[5][6] | Ancient Greece (Hierapolis) |

| 1897 | Scientific development | Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov describes the principles of the conditioned reflex, which, unlike an innate reflex, is only acquired after a period of cerebral learning.[7][8] | |

| 1911 | Scientific development | American psychologist Edward Thorndike develops the theory of law of effect, which addresses the idea of a consequence having an effect on behavior. Thorndike decides to look into this phenomenon by doing research with cats.[9][10][11] | |

| 1920 | Scientific development | Groundbreaking work of behaviorism happens when John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner at Johns Hopkins University conduct the Little Albert experiment, a case study showing empirical evidence of classical conditioning in humans. This study is also an example of stimulus generalization.[12][13] | |

| 1924 | Scientific development | Behaviorally-centered therapeutic approaches appear when American developmental psychologist Mary Cover Jones, a John B. Watson former student, conducts an investigation of the effectiveness of counterconditioning or deconditioning to eliminate anxiety with a 3-year-old boy named Little Peter, who was gradually exposed to a rabbit by means of a rudimentary form of systemic desensitization.[2][14][15][16] | |

| 1950s | Therapy development | South African psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe develops his behavioral therapy.[12] | South Africa |

| 1953 | Scientific development | American scientists Ogden Lindsley, B. F. Skinner, and Harry C. Solomon refer to their use of operant conditioning principles with hospitalized psychotic patients as "behavior therapy".[17] | United States |

| 1953 | Therapy development | American clinical psychologist Albert Ellis in New York establishes the foundations of his Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT).[18][19] | United States |

| 1958 | Literature | Joseph Wolpe publishes his Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition, in which he revealed his ideas. Wolpe claims that it is possible to treat the symptoms of anxiety or phobias by teaching patients to relax and confront their fears. The book is met with skepticism and disdain by the psychiatric community.[20] | South Africa |

| 1958 | Literature | Albert Ellis publishes Rational Psychotherapy, a brief paper marking the beginning of cognitive therapies.[21] | United States |

| 1958 | Literature | The Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior is established.[22] | |

| 1959 | Scientific development | German-born English psychologist Hans Eysenck uses the term "behavior therapy" to refer to a new therapeutic approach based upon the application of "modern learning theory" to the tratment of psychological disorders.[17] | United Kingdom |

| 1959 | Therapy development | Applied behavior analysis originates with Teodoro Ayllon and Jack Michael's study "The psychiatric nurse as a behavioral engineer" that they submit to the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) as part of their doctoral dissertation at the University of Houston[23] | United States |

| 1960s | Scientific development | American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, in Philadelphia, becomes interested in determining the factors involved in the development and maintenance of depression. Beck is widely regarded as the father of cognitive behavioral therapy.[4] | |

| 1961 | Scientific development | Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura conducts a research study that analyzes the way children learn from observing. Bandura concludes hypothesizing that the "subjects exposed to aggressive models would reproduce aggressive acts resembling those of their models and would differ in this respect both from subjects who served nonaggressive models and from those who had no prior exposure to any models".[24] | |

| 1962 | Therapy development | Rational emotive therapy is described by Ellis. The therapy would be later known as Rational emotive behaviour therapy.[25] | |

| 1963 | Scientific development | American professor Arthur Staats publishes his first treatise on what would be a lifelong mission to develop a unified theory of psychology.[26] | United States |

| 1963 | Scientific development | Aaron T. Beck formulates his initial cognitive model of depression in papers.[4] | United States |

| 1967 | Literature | Aaron T. Beck elaborates his theory on depression in his book Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects.[4] | United States |

| 1968 | Literature | The Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis is established at the University of Kansas.[27] | United States |

| 1969 | Literature | An early "cognitive behaviour" text appears with the publication of Principles of Behaviour Modification, by A. Bandura, which argues that certain therapeutic processes, such as covert modelling, are better conceived of as cognitive processes rather than behavioural conditioning.[28] | |

| 1970 | Literature | Masters and Johnson publish Human Sexual Inadequacy, a book that would sparkle hundreds of articles on CBT.[29] | |

| 1971 | Scientific development | Thomas D’Zurilla and Marvin Goldfried publish a comprehensive review of the relevant theory and research related to real-life problem solving. Problem-solving skills refer to the set of cognitive-behavioral activities by which a person attempts to discover or develop effective solutions or ways of coping with real-life problems.[30] | |

| 1976 | Literature | Aaron T. Beck publishes Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders.[4] | United States |

| 1977 | Therapy development | Self-control therapy (SCT) is developed for application with depressed populations.[25] | |

| 1977 | Literature | Journal Behavior Modification is established.[31] | |

| 1978 | Literature | Journal Perspectives on Behavior Science is established.[32] | |

| 1979 | Literature | Philip C. Kendall and Steven D. Hollon publish Cognitive-Behavioural Interventions: Theory, Research and Prodecures.[28] | |

| 1979 | Literature | Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery publish Cognitive Therapy of Depression.[33] | United States |

| 1980 | Literature | Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy is published by David D. Burns, soon popularizing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[34] | |

| 1980 | Scientific development | Nezu and colleagues focus their research activities on the relationship between problem solving and clinical depression, an effort resulting in the development of both a conceptual model of depression and an adapted version of Problem Solving Therapy for depression.[30] | |

| Early 1980s | Therapy development | American psychologist Donald Meichenbaum develops stress inoculation training.[35] | United States |

| 1982 | Therapy development | Steven C. Hayes develops Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in order to create a mixed approach which integrates both cognitive and behavioral therapy.[36] | |

| 1984 | Therapy development | Coping with Depression (CWD) is developed and evaluated as a group intervention for depression.[25] | |

| Late 1980s | Therapy development | Dialectical behavior therapy, a modified form of CBT, is developed by Marsha M. Linehan,[37] a psychology researcher at the University of Washington, to treat people with borderline personality disorder and chronically suicidal individuals.[38] | United States |

| 1990 | Literature | The earliest paper on the subject of clinical effectiveness of Computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (CCBT) in treatment of depression is published.[39] | |

| 1996 | Literature | The first formal description for individual CBT for bipolar disorder is published.[40] | |

| 1999 | Therapy development | CBT is suggested for treatment of internet addiction.[41] | |

| Late 1990s | Therapy development | Inference-based therapy is developed as a form of cognitive therapy for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder.[42][43] | |

| 2000 | Scientific development | A study compares the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. It involves 220 women with bulimia nervosa and followed them for 1 year. The results show that CBT was more effective than IPT in achieving recovery and remission from bulimia nervosa in the short term. However, at the 1-year follow-up, the outcomes of CBT and IPT were similar. The study concludes that while both therapies were effective, IPT took longer to produce clinical change compared to CBT.[44] | United States |

| 2000 | Scientific development | The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines indicate that, among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy have the best-documented efficacy for treatment of major depressive disorder.[45] | United States |

| 2001 | Scientific development | Meta-analyses examining the efficacy of psychological treatments for schizophrenia reveals a beneficial effect of CBT on positive symptoms (i.e., delusions and/or hallucinations) of schizophrenia.[46] | |

| 2004 | Scientific development | According to a review by INSERM (Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale) of three methods, cognitive behavioral therapy is either "proven" or "presumed" to be an effective therapy on several specific mental disorders.[47] | France |

| 2004 | Scientific development | CBT for bulimia nervosa is given an "A" evidence grade by the United Kingdom's National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines, which indicates that CBT is an evidence-based treatment supported by multiple randomized control trials.[48] | |

| 2005 | Scientific development | Study finds evidence that CBT is a particularly promising adjunct to pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia patients who suffer from an acute episode of psychosis rather than a more chronic condition.[46] | |

| 2006 | Recommendation | The British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) updates its recommendations on cognitive behavior therapy in the National Health Service, recommending two computerized CBT packages for managing depression and phobia based on new evidence. Computerized CBT provides treatment through interactive computer interfaces. NICE recognizes the preference for face-to-face therapy, but limited availability hinders access. Computerized packages are considered safe and deliver similar guidance. However, it is stated that they may not be suitable for severe depression. NICE selected two packages based on their effectiveness and cost after reviewing five options.[49] | United Kingdom |

| 2008 | Literature | Rhena Branch and Rob Willson publish Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies.[50] | |

| 2012 | Scientific development | According to Cox, Lyn Yvonne Abramson, Patricia Devine, and Hollon, cognitive behavioral therapy can also be used to reduce prejudice towards others. This other-directed prejudice can cause depression in the "others", or in the self when a person becomes part of a group he or she previously had prejudice towards (i.e. deprejudice).[51] | |

| 2012 | Scientific development | Randomized controlled trial shows Compassion-focused therapy to be a safe and clinically effective treatment option for psychosis patients.[52] | |

| 2013 | Literature | Kenneth A. Perkins, Cynthia A. Conklin, and Michele D. Levine publish Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Smoking Cessation.[53] | |

| 2013 | Scientific development | Study finds strong efficacy for CBT of anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, bulimia, anger control problems, and general stress. There is also evidence for the efficacy of CBT for cannabis dependence.[46] | |

| 2014 | Scientific development | The British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends preventive CBT.[54][55] | |

| 2015 | Scientific development | A meta-analysis reveals that the positive effects of CBT on depression have been declining since 1977. The overall results show two different declines in effect sizes: 1) an overall decline between 1977 and 2014, and 2) a steeper decline between 1995 and 2014. Additional sub-analysis reveal that CBT studies where therapists in the test group were instructed to adhere to the Beck CBT manual had a steeper decline in effect sizes since 1977 than studies where therapists in the test group were instructed to use CBT without a manual. The authors reported that they were unsure why the effects were declining but did list inadequate therapist training, failure to adhere to a manual, lack of therapist experience, and patients' hope and faith in its efficacy waning as potential reasons. The authors did mention that the current study was limited to depressive disorders only.[56] | |

| 2017 | Scientific development | Study reports CBT showing an advantage over interpersonal psychotherapy for major depression disorders.[57] | |

| 2018 | Scientific development | Study finds CBT and psychoeducation to be effective treatment modalities in dialysis patients; however, psychoeducation is found to achieve more significant alleviation from depression. Referring patients to psychoeducation is recommended.[58] |

Numerical and visual data

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 22, 2021.

| Year | cognitive behavioral therapy | cognitive behavioral therapy effectiveness | cognitive behavioral therapy for depression | cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia | cognitive behavioral therapy for ptsd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 3,410 | 3,910 | 1,920 | 229 | 451 |

| 1985 | 4,880 | 5,660 | 3,580 | 417 | 1,020 |

| 1990 | 7,920 | 8,140 | 5,810 | 602 | 1,800 |

| 1995 | 12,500 | 11,400 | 8,930 | 917 | 3,340 |

| 2000 | 23,000 | 21,500 | 18,000 | 1,950 | 6,460 |

| 2002 | 27,700 | 23,500 | 20,400 | 2,390 | 7,790 |

| 2004 | 34,500 | 21,300 | 21,500 | 2,770 | 9,810 |

| 2006 | 48,700 | 26,000 | 27,900 | 3,450 | 12,200 |

| 2008 | 61,500 | 31,400 | 36,500 | 4,440 | 14,700 |

| 2010 | 74,100 | 38,000 | 44,500 | 5,320 | 16,600 |

| 2012 | 82,100 | 45,300 | 57,100 | 6,810 | 18,600 |

| 2014 | 100,000 | 58,400 | 68,900 | 7,990 | 68,700 |

| 2016 | 89,400 | 63,200 | 71,000 | 9,490 | 22,400 |

| 2017 | 79,700 | 63,100 | 67,300 | 10,300 | 23,300 |

| 2018 | 68,400 | 62,400 | 63,700 | 11,300 | 24,300 |

| 2019 | 62,800 | 61,100 | 60,700 | 12,100 | 25,800 |

| 2020 | 48,300 | 53,900 | 50,000 | 14,800 | 25,600 |

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Cognitive behavioral therapy (Topic and Search term) from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[59]

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Cognitive behavioral therapy from 1900 to 2019.[60]

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Cognitive behavioral therapy on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to December 2020.

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

- Sample questions section

- List of cognitive–behavioral therapies

- Category:Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Category:Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapists

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Bieling, Peter J.; McCabe, Randi E.; Antony, Martin M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Groups.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rachman, S (1997). "The evolution of cognitive behaviour therapy". In Clark, D; Fairburn, CG; Gelder, MG. Science and practice of cognitive behaviour therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-19-262726-1.

- ↑ "The Development of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy". foundationsrecoverynetwork.com. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Sudak, Donna M.; Trent Codd, R.; Fox, Marci G.; Ludgate, John W.; Sokol, Leslie; Reiser, Robert P.; Milne, Derek L. Teaching and Supervising Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

- ↑ Donald Robertson (2010). The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. London: Karnac. p. xix. ISBN 978-1855757561.

- ↑ Mathews J (2015). "Stoicism and CBT: Is Therapy A Philosophical Pursuit?". Virginia Counseling. Virginia Counseling.

- ↑ Vincent, Jean-Didier; Lledo, Pierre-Marie. The Custom-Made Brain: Cerebral Plasticity, Regeneration, and Enhancement.

- ↑ A Study Guide for Psychologists and Their Theories for Students: IVAN PAVLOV. Gale.

- ↑ Cash, Adam. Psychology For Dummies.

- ↑ Causal Learning: Advances in Research and Theory.

- ↑ Saugstad, Per. A History of Modern Psychology.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Trull, T. J. (2007). Clinical psychology (7th Ed). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- ↑ "John B. Watson Biography". psychologicalharassment.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ Freeman, Arthur. Encyclopedia of Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

- ↑ Klein, Stephen B. Learning: Principles and Applications.

- ↑ Jones, M. C. (1924). "The Elimination of Children's Fears". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 7 (5): 382–390. doi:10.18037/h0072283.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Franks, Cyril M. New Developments in Behavior Therapy: From Research to Clinical Application.

- ↑ Personality Theories. p. 428.

- ↑ Dryden, Windy. Dryden's Handbook of Individual Therapy.

- ↑ "Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition". books.google.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ "Rational and Irrational Beliefs: Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice". oxfordscholarship.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ "The Journal of The Experimental Analysis of Behavior at Zero, Fifty, and One Hundred". doi:10.1901/jeab.2008.89-111.

- ↑ Pierce, W. David; Cheney, Carl D. (June 16, 2017) [1995]. Behavior Analysis and Learning: A Biobehavioral Approach (6 ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 978-1138898585.

- ↑ Hardaway, Robert M. The Great American Housing Bubble: The Road to Collapse.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Hunot, V; Moore, THM; Caldwell, D; Davies, P; Jones, H; Furukawa, TA; Lewis, G; Churchill, R. "Cognitive behavioural therapies versus treatment as usual for depression (Protocol)". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008699.

- ↑ "Why a Unified Theory of Psychology Is Impossible". psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Baer, Donald M. (1993). "A brief, selective history of the Department of Human Development and Family Life at the University of Kansas: The early years". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 26 (4): 569–570. PMC 1297894

. PMID 16795815. doi:10.1901/jaba.1993.26-569.

. PMID 16795815. doi:10.1901/jaba.1993.26-569.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Cognitive Behaviour Therapies (Windy Dryden ed.).

- ↑ Comprehensive Handbook of Cognitive Therapy (L.E. Beutler, Karen Simon ed.).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Nezu, Arthur M.; Nezu, Christine Maguth; D’Zurilla, Thomas J. "Problem-Solving Therapy" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ "Behavior Modification". journals.sagepub.com. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Perspectives on Behavior Science". abainternational.org. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Cognitive Therapy of Depression". books.google.com.

- ↑ "History of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy". National Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ↑ "Addiction A-Z". addiction.com. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ↑ Freeman, Arthur (2010). Cognitive and Behavioral Theories in Clinical Practice. Newyork, NY: The Guilford Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-60623-342-9.

- ↑ "What is DBT?". The Linehan Institute. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ↑ Linehan, Marsha M. (2014). "DBT Skills Training Manual" (PDF). www.guilford.com (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ↑ "Brief Discussion on Current Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy". link.springer.com. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Bieling, Peter J.; McCabe, Randi E.; Antony, Martin M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Groups.

- ↑ Smith, Robert L. Treatment Strategies for Substance Abuse and Process Addictions.

- ↑ O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1995). Inference processes in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Some clinical observations. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 887-96.

- ↑ O'Connor, K., & Robillard, S. (1999). A cognitive approach to the treatment of primary inferences in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13, 359-75.

- ↑ Stewart Agras, W.; Walsh, B. Timothy; Fairburn, Christopher G. "A Multicenter Comparison of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Bulimia Nervosa". doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459.

- ↑ Hirschfeld, Robert M.A. (2006). "Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, 2nd Edition" (PDF). APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Comprehensive Guidelines and Guideline Watches. 1. ISBN 978-0-89042-336-3.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Hofmann, Stefan G.; Asnaani, Anu; Vonk, Imke J.J.; Sawyer, Alice T.; Fang, Angela. "The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses". PMID 23459093. doi:10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1.

- ↑ INSERM Collective Expertise Centre (2000). "Psychotherapy: Three approaches evaluated". PMID 21348158.

- ↑ Zweig, Rene D.; Leahy, Robert L. Treatment Plans and Interventions for Bulimia and Binge-Eating Disorder.

- ↑ Mayor, Susan (4 March 2006). "NICE advocates computerised CBT". BMJ. 332 (7540): 504.3. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7540.504-b.

- ↑ "Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook For Dummies". books.google.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ↑ Cox, W. T. L.; Abramson, L. Y.; Devine, P. G.; Hollon, S. D. (2012). "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression: The Integrated Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (5): 427–49. PMID 26168502. doi:10.1177/1745691612455204.

- ↑ Braehler, Christine; Gumley, Andrew; Harper, Janice; Wallace, Sonia; Norrie, John; Gilbert, Paul (24 October 2012). "Exploring change processes in compassion focused therapy in psychosis: Results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial". Clinical Psychology. 52 (2): 199–214. PMID 24215148. doi:10.1111/bjc.12009.

- ↑ Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Smoking Cessation.

- ↑ "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: updated NICE guidance for 2014". National Elf Service. 2019-03-19.

- ↑ "Psychosis and schizophrenia". nice.org.uk.

- ↑ Johnsen, TJ; Friborg, O (July 2015). "The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: A meta-analysis.". Psychological Bulletin. 141 (4): 747–68. PMID 25961373. doi:10.1037/bul0000015.

- ↑ Zhou, She-Gang; Hou, Yan-Fei; Liu, Ding; Zhang, Xiao-Yuan. "Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Versus Interpersonal Psychotherapy in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". PMC 5717864

. PMID 29176143. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.219149. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

. PMID 29176143. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.219149. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ Al saraireh, Faris A.; Aloush, Sami M.; Azzam, Manar Al; Bashtawy, Mohammed Al. "The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy versus Psychoeducation in the Management of Depression among Patients Undergoing Haemodialysis". doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1406022.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral therapy". trends.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cognitive behavioral therapy". books.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.