Difference between revisions of "Timeline of parasitology"

(→Google Ngram Viewer) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Full timeline== | ==Full timeline== | ||

| Line 346: | Line 323: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 19, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! "parasitology" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1900 || 37 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1910 || 164 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1920 || 308 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1930 || 409 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1940 || 474 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1950 || 800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960 || 1,580 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || 2,620 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 3,870 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 6,730 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 11,600 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 22,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 27,300 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Parasitology gshco.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Trends === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comparative chart below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Virology (Field of study), Parasitology (Field of study), and Bacteriology (Field of study), from January 2004 to Month 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F021ypg,%2Fm%2F080y1,%2Fm%2F0gx21vp |website=Google Trends |access-date=3 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology gt.png|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comparative chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for bacteriology, virology and parasitology, from 1800 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=parasitology%2Cvirology%2Cbacteriology&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cparasitology%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cvirology%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cbacteriology%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cparasitology%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cvirology%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cbacteriology%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=3 April 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology ngram.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|parasitology}}, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to February 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Parasitology |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Parasitology&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=3 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Parasitology wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comparative chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia articles {{w|parasitology}}, {{w|virology}} and {{w|bacteriology}}, on desktop, from July 2015 to February 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?pages[0]=Parasitology&pages[1]=Virology&pages[2]=Bacteriology&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=desktop |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=3 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

==Meta information on the timeline== | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

Latest revision as of 21:47, 25 March 2024

This is a timeline of parasitology, attempting to focus on human parasitology.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Prehistory | Since the emergence of Homo sapiens in eastern Africa, humans spread throughout the world, possibly in several waves, migrating to and inhabiting virtually the whole of the face of the Earth, bringing some parasites with them and collecting others on the way.[1] During the First Agricultural Revolution, from hunting and gathering to settled agriculture, humans acquire parasites from animals with which they come in contact during agricultural practices.[1] |

| Ancient history | Many detailed descriptions of various diseases that might or might not be caused by parasites, specifically fevers, are found in the writings of Greek physicians between 800 to 300 BC, such as the Corpus Hippocratorum by Hippocrates, and from physicians from other civilizations including China from 3000 to 300 BC, India from 2500 to 200 BC, Rome from 700 BC to 400 AD, and the Arab Empire in the latter part of the first millennium. The descriptions of infections become more accurate and Arabic physicians, particularly Rhazes (AD 850 to 923) and Avicenna (AD 980 to 1037), write important medical works that contain a great deal of information about diseases clearly caused by parasites.[1] |

| Middle Ages | The medical literature is very limited during this time, but there are many references to parasitic worms. In some cases, they are recognized as the possible causes of disease but in general, the writings of the period reflect the culture, beliefs, and ignorance of the time.[1] |

| Modern history | Beginning at around 1500, The slave trade, which would flourish for three and a half centuries from about 1500, bring new parasites to the New World from the Old World.[1] The first definitive reports of lymphatic filariasis begin to appear in the 16th century.[1] In the 17th and 18th centuries, the science of helminthology develops, following the reemergence of science and scholarship during the Renaissance period.[1] By the beginning of the 17th century, it becomes apparent that there are two very different kinds of tapeworm (broad and taeniid) in humans. The scientific study of the taeniid tapeworms of humans can be traced to the late 17th century.[1] Modern parasitology develops in the 19th century with accurate observations by several researchers and clinicians. |

| Present time | Currently, known parasites infecting humans has now increased to about 300 species.[1] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Country/region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 150,000 BP | Prelude | Homo sapiens emerge in eastern Africa.[1] | |

| 8,000 BC | Infection | American biological anthropologist Frank B. Livingstone proposes in 1958 that Plasmodium falciprum, the deadliest of 4 or 5 parasites that cause human malaria, hopped from chimps to humans about this time as human hunter-gatherers begin settling on farms.[2] | |

| 5,000 BC | Infection | Nematode eggs discovered recently in a frozen human body (Ötzi in Austrian Alps, date from this time.[3] | Austria |

| 3,000–400 BC | Medical development | The first written records of what are almost certainly parasitic infections come from this period of Egyptian medicine, particularly the Ebers papyrus of 1500 BC discovered at Thebes.[1] | |

| 2,277 BC | Infection | Ascaris lumbricoides eggs are found in human coprolites from Peru dating from this time.[1] | Peru |

| 2,000 BC | Infection | Taenia and Schistosoma ova in Egyptian mummies date from this time.[3] | Egypt |

| 1,550 BC | Scientific development | The Ebers papyrus in Egypt gives reference to roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), threadworms (Enterobius vermicularis), and tapeworms (Taenia saginata). These records can be confirmed by the recent discovery of calcified helminth eggs in mummies dating from 1200 BC.[1][3] | Egypt |

| 1,300 BC – 1,234 BC | Biblical references to Dracunculus medinensis in the Red Sea region date from this time.[3] | ||

| 700 BC – 600 BC | Infection | Records of Dracunculus medinensis worms from Mesopotamia date from this time.[3] | Irak |

| 430 BC | Scientific development | Greek physician Hippocrates describes Ascaris, Oxyuris, adult Taenia, and malaria.[1][3] | |

| 342 BC | Scientific development | Greek scientist Aristotle establishes a first classification system for animals in his Historia animalium and describes flat and round worms.[3] | Greece |

| 300 BC | Scientific development | Chinese description of threadworms, tapeworms, hookworms, and hookworm disease is recorded.[3] | China |

| 20 AD | Scientific development | Roman encyclopaedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus recognizes tapeworms Taenia, Tinea, Taeniola, vermes cucurbitini (tapeworm proglottids), "hailstones" (cysticersi), and roundworms, lumbrici teretes (Ascaris lumbricoides).[3] | |

| 62 AD | Scientific development | In their Historia naturalis, Romans Lucius Columella and Plinius secundus report on parasitic animal diseases.[3] | Italy |

| 129 AD – 199 AD | Scientific development | Greek–Roman scientist Claudius Galenus recognizes three types of worms: roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), threadworms (Enterobius vermicularis), tapeworms (Taenia sp.), and also cysticerci in livers of slaughtered animals.[3] | |

| 625 AD–690 AD | Scientific development | Byzantine Greek physician Paul of Aegina (AD 625 to 690) clearly describes Ascaris, Enterobius, and tapeworms and gives good clinical descriptions of the infections they cause.[1] | |

| 980 AD – 1037 AD | Scientific development | Persian scientist Avicenna, in his book Liber canonis medicinae, reports on malaria and many worms, especially on Dracunculus (which today in French is still called Fil d'Avicenne).[3][1][3] | Iran |

| 1,150 AD | Medical development | German nun Hildegard of Bingen publishes De causis et curis morborum, which describes plant-based methods of treating worms.[3] | Germany |

| 1498 | Medical development | Italian Dominican Girolamo Savonarola publishes Tractatus de vermibus, which describes the occurrence and treatment (by mercury) of worm-infected humans.[3][4] | Italy |

| 1558 | Scientific development | There are accounts of what are possibly cysticerci in humans by Johannes Udalric Rumler.[5] [1][6] | |

| 1674 | Scientific development | Georgius Hieronymus Velschius initiates the scientific study of the nematode Dracunculus and the disease it causes.[1] | |

| 1681 | Scientific development | Giardia duodenalis, also known as Giardia lamblia or Giardia intestinalis, becomes the first parasitic protozoan of humans seen by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.[1] | |

| 1688 | Scientific development | Philip Hartmann conducts the first reliable accounts of cystercerci as parasites of some kind.[1] | |

| 1699 | Scientific development | Dutch scientist Nicolaas Hartsoeker and J. Andry from France propose that helminth infections derive from oral intake of excreted worm eggs.[3] | |

| 1707–1778 | Scientific development | Swedish botanist Carl von Linné describes and names six helminth worms, Ascaris lumbricoides, Ascaris vermicularis (= Enterobius vermicularis), Gordius medinensis (= Dracunculus medinensis), Fasciola hepatica, Taenia solium, and Taenia lata (= Diphyllobothrium latum).[1] | |

| 1721 | Scientific development | English naval surgeon, John Atkins conducts the first definitive accounts of sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis).[1] | |

| 1750 | Scientific development | Swiss biologist Charles Bonnet conducts the first accurate description of the proglottids.[7][8][1] | |

| 1756 | Scientific development | English physician Alexander Russel, in Aleppo, discovers skin leishmaniasis.[3] | Syria |

| 1766 | Scientific development | German clinician and natural historian Pierre Simon Pallas shows a parasitic link to the cysts.[9] | |

| 1770 | Scientific development | French surgeon André Mongin describes the worm loiasis (Eye Worm) passing across the eye of a woman in Santa Domingo, in the Caribbean, and recounts how he tried unsuccessfully to remove it. This is the first verified report of a subconjunctival worm.[10][1][11][12] | Dominican Republic |

| 1778 | Medical development | French surgeon François Guyot becomes the first to successfully remove the worm and give the name loa loa from the eye of a male slave from West Africa.[13][10] | |

| 1782 | Scientific development | German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goetze first describes microscopically the scolices of the larva of Echinococcus.[14] | |

| 1784 | Scientific development | German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze perceives the similarities between the heads of tapeworms found in human intestinal tract and the invaginated heads of Cysticercus cellulosae in pigs.[15][1] | |

| 1786 | Scientific development | Werner and Fischer publish treatise Vermis intestinalis brevis expositio, describing under the name finna humana, a kind of hydatid found in the interior of a muscle of a soldier who has been drowned.[16] | |

| 1786 | Scientific development | Echinococcus granulosus is discovered by Batsch.[14] | |

| 1790 | Scientific development | An understanding of the life cycle of the parasite Diphyllobothrium latum begins when Danish physician Peter Christian Abildgaard observes that the intestine of sticklebacks contains worms that resemble the tapeworms found in fish-eating birds.[1] | |

| 1793 | Scientific development | Treutler speaks of two kinds of hydatids found in the human body, one of which he calls taenia alba punctata, and the other taenia visceralis.[16] | |

| 1798 | Scientific development | Italian physician Francesco Redi publishes Osservazioni interno agli animali viventi, which describes about 108 different worms, and publishes a detailed study on Fasciola hepatica. Francesco Redi is considered the Father of Parasitology.[3] | Italy |

| 1800 | Scientific development | Zeder describes the echinococcus hominis, which is also observed in monkeys, and which Rudolphi places in the family of entozoa cystica.[16] | |

| 1801 | Scientific development | Karl Rudolphi publishes Entozoorum historia naturalis, which describes the taxonomy of all available parasites.[3] | Germany |

| 1801 | Scientific development | French naturalist Jean Baptiste Lamarck publishes his Pilosophie Zoologique, which presents the first general theory of evolution.[3] | France |

| 1806 | Scientific development | French physician Cullerier, senior surgeon at the civil Parisian Venereal Hospital, is the first to describe a case of hydatid cyst of the bone.[14] | France |

| 1807 | Scientific development | French anatomist François Chaussier reports a case of spinal hydatid disease.[17] | France |

| 1808 | Scientific development | Swedish naturalist Karl Asmund Rudolphi coins the term echinococcus.[14][18][19] | |

| 1818 | Scientific development | Cloquet writes a full description of the different varieties of hydatids, dividing each genus into several species, and minutely detailing their several peculiarities.[16] | |

| 1819 | Scientific development | Carl Asmund Rudolphi discovers adult female worms containing larvae of Dracunculus. | |

| 1819 | Medical development | The first patient treated surgically for spinal hydatidosis is reported by Reydellet.[20][21][14] | |

| 1827 | Scientific development | Montansey describes the brain of an idiot-epileptic woman containing a large number of cerebellar and cerebral hydatid cysts.[14] | |

| 1835 | Scientific development | James Paget, then a medical student at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London, discovers nematode parasite Trichinella spiralis in humans.[1][22][23] | United Kingdom |

| 1836 | Scientific development | British army officer D. Forbes, serving in India, finds and describes the larvae of Dracunculus medinensis in water.[1] | |

| 1847 | Scientific development | Dairo Fujii records Katayama disease –a severe dermatitis, in the Kwanami district in Japan.[1][24][25] | |

| 1848 | Medical development | The first English account of the removal of worms from the eye is that by William Loney.[1][26] | |

| 1849 | Scientific development | English chemist William Prout records the condition of chyluria in his book On the Nature and Treatment of Stomach and Renal Diseases.[27][28][1] | |

| 1850 | Scientific development | German physician Theodor Bilharz, in Cairo, Egypt, discovers Schistosoma haematobium.[3] | Egypt |

| 1853 | Scientific development | German physiologist Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold demonstrates that Echinococcus cysts from sheep give rise to adult tapeworms when fed to dogs.[1][29][30] | |

| 1855 | Scientific development | Rudolf Virchow first suggests the helminthic nature of alveolar hydatid disease caused by Echinococcus multilocularis.[14][31] | |

| 1855 | Scientific development | German physician Gottlieb Küchenmeister discovers that tapeworms develop from cysticeri after feeding convicts with cysticerci excised from pork meat, and finding adult tapeworms in the intestine after autopsy.[5][3] | Germany |

| 1859 | Scientific development | German zoologist Rudolf Leuckart and Rudolph Virchow independently discover the life cycle of Trichinella spiralis.[3] | Germany |

| 1859 | Scientific development | German cellular pathologist Rudolf Virchow writes his book Cellular Pathology, which would become the foundation for all microscopic study of disease.[32][33][1] | Germany |

| 1860 | Scientific development | Friedrich Zenker provides the first clear evidence of transmission of Trichinella spiralis from animal to human.[34][35][36] | |

| 1863 | Scientific development | French surgeon Jean Nicolas Demarquay first identifies tissue worms when studying samples of a Cuban patient affected by hydrocele.[37][38][13] | |

| 1863 | Scientific development | Rudolf Leuckart discovers small cyclophyllid tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis.[14][39][40] | |

| 1863 | Scientific development | Austrian zoologist Karl Moritz Diesing discovers parasitic tapeworms Echinococcus oligarthus.[14][41][42] | |

| 1863 | Scientific development | German pathologist Bernhard Naunyn finds adult tapeworms in dogs fed with hydatid cysts from a human.[1][9][43] | |

| 1863 | Scientific development | English scientist Thomas Spencer Cobbold suggests that snails might be the intermediate host of schistosomes.[3] | United Kingdom |

| 1866 | German physician Otto Wucherer discovers microfilariae in the urine of a patient in Brazil.[44][1][45] | Brazil | |

| 1867 | Scientific development | Rudolf Leuckart describes the life cycle of Echinococcus granulosus.[3] | Germany |

| 1868 | Scientific development | J. H. Oliver observes that Taenia saginata tapeworm infections occur in individuals who have eaten “measly” beef.[1] | |

| 1870 | Scientific development | Russian naturalist Alexei Fedchenko describes the life cycle of nematode parasite Dracunculus, including the stages in a crustacean intermediate host.[46][47][48] | |

| 1872 | Scientific development | British physician Timothy Lewis detects microfilaria in blood samples for the first time while working in Calcutta, India.[13] | |

| 1873 | Scientific development | Friedrich Lösch in Russia discovers the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica, a serious protozoan pathogen which is considered to be the third cause of parasitic death in the world.[49][50][51] | |

| 1875 | James McConnell first recognizes the human liver fluke Clonorchis sinensis.[1] | ||

| 1875 | Scientific development | Irish naval surgeon John O'Neill first observes the microfilariae of onchocerciasis when examining skin samples from patients in Ghana.[13] | |

| 1875 | Scientific development | Clonorchis sinensis is first discovered in the bile ducts of a Chinese man in India.[52] | |

| 1876 | Scientific development | Strongyloides stercoralis and the disease strongyloidiasis are both discovered by Louis Alexis Normand, a physician to the French naval hospital at Toulon.[1] | |

| 1876 | Scientific development | English parasitologist Joseph Bancroft observes and describes adult Wuchereria banchrofti worms.[3][1] | Australia |

| 1877 | Scientific development | Scottish physician Patrick Manson describes the life cycle of elephantiasis, which is caused by nematode Wuchereria bancrofti.[1][13] | |

| 1879 | Scientific development | B.S. Ringer discovers discovers the first case of paragonimiasis when he finds the fluke Paragonimus westermani in the lungs of a Portuguese patient while performing an autopsy in Formosa (Taiwan).[53][54][1] | |

| 1880 | Scientific development | Eggs in the sputum are recognized independently by Scottish physician Patrick Manson and German physician Erwin Von Baelz.[1][54][55] | |

| 1880 | Scientific development | French physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran describes malaria stages within erythrocytes.[3] | |

| 1881 | Scientific development | Rudolf Leuckart and A. P. Thomas independently describe the life cycle of Fasciola hepatica.[3] | Germany, United Kingdom |

| 1883 | Scientific development | Rudolf Leuckart discovers the alternation of generations involving parasitic and free-living phases.[1] | Germany |

| 1885 | Scientific development | Greek physician Stephanos Kartulis finds amoebae in intestinal ulcers in patients suffering from dysentery in Egypt.[56][57][58] | |

| 1889 | Medical development | Irish surgeon Henry Widenham Maunsell operates successfully on a case of probable subtentorial hydatid cyst in an 18-year-old boy in New Zealand.[14] | New Zealand |

| 1890 | Scientific development | British ophtalmologist Stephen McKenzie identifies microfilaria in cases of loiasis.[13][1] | |

| 1890 | Medical development | Australians Graham and Clubb are the first to report the successful removal of an undoubted hydatid cyst of the brain.[14] | |

| 1891 | Scientific development | William Thomas Councilman and Henri Lafleur, at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, establish a definitive statement of what is known about the pathology of amoebiasis, much of which is still valid today.[1] | |

| 1891 | Scientific development | Trypanosomes are seen in human blood by French physician Gustave Nepveu.[1] | |

| 1892 | Konstantin Wingradoff produces the first records of Opisthorchis infections in humans.[1] | ||

| 1893 | Scientific development | American scientists Theobald Smith and F.L. Kilbourne identify the transmission of Babesia bigemina by ticks (Boophilus annulatus).[3] | United States |

| 1895 | Scientific development | Scottish pathologist David Bruce shows that the tsetse fly is the vector of animal trypanosomes.[3] | |

| 1895 | Medical development | Scottish ophtalmologist Douglas Argyll-Robertson describes the clinical presentation of loiasis.[13] Argyll-Robertson records the swellings (now known as Calabar swellings) in Old Calabar in Nigeria.[1] | |

| 1897 | Scientific development | English Army doctor Sir Donald Ross, in India, proves that avian malaria is transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. In the same year, Bignami, Bastianelli and Grassi in Italy do the same for human malaria.[3] | India, Italy |

| 1898 | Scientific development | German physician Robert Koch describes Theileria parva, the agent of East Coast fever.[3] | |

| 1898 | Scientific development | French physician Paul-Louis Simond succeeds in demonstrating the transmission of plague by rat fleas.[3] | |

| 1899 | Epidemiology | American parasitologist Charles Wardell Stiles identifies progressive pernicious anemia seen in the southern United States as being caused by the hookworm Ancylostoma duodenale.[59] | United States |

| 1900 | Scientific development | Team in Cuba led by United States Army physician Walter Reed demonstrates the transmission of yellow fever by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti).[3] | Cuba |

| 1902 | Scientific development | British parasitologist Joseph Everett Dutton identifies the trypanosome that causes Gambian or chronic sleeping sickness (T. b. gambiense) in humans.[1] Dutton describes the first case of human trypanosomiasis.[60] | |

| 1903 | Scientific development | British scientists William Boog Leishman in England and Charles Donovan in India, independently describe Leishmania donovani, the agent of Kala-azar disease (leishmaniasis).[3] | |

| 1903 | Scientific development | The first cases of human polycystic echinococcosis, a disease resembling alveolar echinococcosis, emerge in Argentina.[41] | Argentina |

| 1904 | Scientific development | German helminthologist Arthur Loos in Cairo discovers the transmission of the hookworm.[3] | Egypt |

| 1904 | Scientific development | Japanese parasitologist Fujiro Katsurada discovers and describes the worm Schistosoma japonicum.[1][61][24] | |

| 1905 | Scientific development | E. Franke is credited with the first suggestion that trypanosomes of the subgenus trypanozoon could change immunologically during the course of an infection, and thus survive the onslaught of their host's antibodies.[62] | |

| 1906 | Journal | Sir Ronald Ross establishes journal Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology.[63] | United Kingdom |

| 1906 | Scientific development | American physician Howard T. Ricketts records the tick Dermacentor andersoni as being a vector of the agents of the Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[3] | |

| 1906 | Scientific development | German zoologist Fritz Schaudinn describes Entamoeba histolytica as a human parasite introducing bloody diarrhea.[3] | |

| 1907 | Scientific development | American parasitologist Ernest Tyzzer describes stages of the genus Cryptosporidium.[3] | |

| 1907 | Medical development | German chemist Paul Ehrlich proposes the drug trypan red against trypanosomiasis.[3] | |

| 1908 | Scientific development | French bacteriologist Charles Nicolle and L.H. Manceaux in North Africa describe Toxoplasma gondii in a rodent.[3] | |

| 1908 | Journal | Cambridge University Press journal Parasitology is first published.[64] | United Kingdom |

| 1909 | Program launch | The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease is organized in the United States, as a result of a gift of US$1 million from John D. Rockefeller.[65] | |

| 1909 | Scientific development | Friedrich Kleine (a colleague of Robert Koch) demonstrates the essential role of the tsetse fly in the life cycle of trypanosomes.[1][66][67] | |

| 1909 | Scientific development | Two teams led by French scientist Charles Nicolle in Tunis and Howard Taylor Ricketts in Mexico prove that the louse Pediculus humanus corporis is the vector of the typhus-causing rickettsia.[3] | Tunis, Mexico |

| 1910 | Scientific development | Scottish physician Patrick Manson confirms that loiasis is caused by roundworms.[13] | |

| 1910 | Scientific development | Italian bacteriologist Antonio Carini discovers Pneumocystis carinii in rats.[3] | |

| 1910 | Scientific development | British parasitologists John William Watson Stephens and Harold Fantham describe Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, the cause of Rhodesian or acute sleeping sickness.[1][68][69] | |

| 1912 | British parasitologist Robert Thompson Leiper confirms biting flies, Chrysops spp. as the transmission vector in loiasis.[13][1] | ||

| 1912 | Kinghorn and Yorke show that Trypanosoma rhodesiense transmission is due to bites of tsetse flies of the genus Glossina.[68][70] | ||

| 1914 | Journal | The Journal of Parasitology by the American Society of Parasitologists is first published.[71] | United States |

| 1915 | Scientific development | Guatemaltecan physician Rodolfo Robles describes the so-called "American onchocerciasis", which is caused by a filarial parasite.[13][72][73] | |

| 1915 | Scientific development | The uncommon intestinal parasite Isospora belli is discovered by Woodcock.[74][75][76][77] | |

| 1921 | Scientific development | Edouard and Etienne Sergent demonstrate the experimental proof of transmission to humans by sandflies belonging to the genus Phlebotomus.[1][78][79][80] | |

| 1923 | Jouenal | The journal Annales de parasitologie humaine et comparee is first published.[81] | France |

| 1924 | Organization | The American Society of Parasitologists is founded.[82] | United States |

| 1928 | Scientific development | Australian professor of surgery, Sir Harold Robert Dew, publishes the first classic book on hydatid disease.[14][83][84][85] | |

| 1933 | Scientific development | Yoshino describes with great histologic detail the early development of cysticerci in pigs.[5] | |

| 1947 | Medical development | American chemist Redginal I. Hewitt develops an effective antifilarial treatment with diethylcarbamazine.[13][86][87] | |

| 1951 | Journal | Journal Experimental Parasitology is first published.[88] | |

| 1954 | Scientific development | American physician Robert Rendtorff produces unambiguous evidence linking the parasite Giardia duodenalis with Giardiasis.[1] | |

| 1956 | Scientific development | Clonorchis sinensis eggs are detected in desiccated fecal remains from a mummy of the Ming dynasty, in the Guangdong province of China.[52] | |

| 1962 | Organization | The Société Française de Parasitologie (English: "French Society of Parasitology") is founded.[89] | France |

| 1962 | Scientific development | Rockefeller Institute scientist Norman Stoll describes hookworm infection as an extremely dangerous one because its damage is “silent and insidious.”[90][91][92][93] | |

| 1963 | Journal | Journal Advances in Parasitology is first published.[94] | United States |

| 1966 | Organization | The European Federation of Parasitologists is founded.[95] | |

| 1969 | Scientific development | Keith Vickerman elaborates antigenic variation, the mechanism of how the parasite evades the immune response.[96][97][98] | |

| 1971 | Journal | The International Journal for Parasitology is first published.[99] | |

| 1972 | Scientific development | Rausch and Bernstein discover Echinococcus vogeli. This is the last discovery concerning the Echinococcus species.[14] | |

| 1976 | Scientific development | Nime and Meisel independently record Cryptosporidium parvum in humans.[1][100][101] | |

| 1977 | Medical development | Japanese physician Satoshi Omura develops a new, highly effective drug called ivermectin.[13][102][103] | |

| 1979 | Journal | Journal Systematic Parasitology is established.[104] | |

| 1980 | Epidemiology | Cryptosporidium parvum is recognized to be a common, serious primary cause of outbreaks as well as sporadic cases of diarrhea in certain mammals.[100] | |

| 1983 | Epidemiology | Cryptosporidium parvum emerges with AIDS, as a life-threatening disease within this sub-population.[100] | |

| 1987 | American physicians Pindaros Roy Vagelos and William Campbell persuade Merck&Co. to donate the drug ivermectin to establish the first filarial eradication programs in the world.[13][13] | ||

| 1993 | Epidemiology | Cryptosporidium parvum reaches the public domain when it becomes widely recognized as the most serious, and difficult to control, cause of water-borne-related diarrhea.[100] | |

| 2001 | Program launch | The 54th World Health Assembly passes a resolution demanding member states to attain a minimum target of regular deworming of at least 75% of all at-risk school children by the year 2010.[105] | |

| 2008 | Program launch | United States President Bill Clinton announces a mega-commitment at the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) 2008 Annual Meeting to de-worm 10 million children.[106] | |

| 2008 | Journal | Journal Parasites & Vectors is launched.[107] | |

| 2009 | Scientific development | Schistosoma haematobium–Schistosoma bovis hybrids are described in northern Senegalese children.[108] | Senegal |

| 2015 | Epidemiology | Hookworm infected about 428 million people in the year.[109] |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

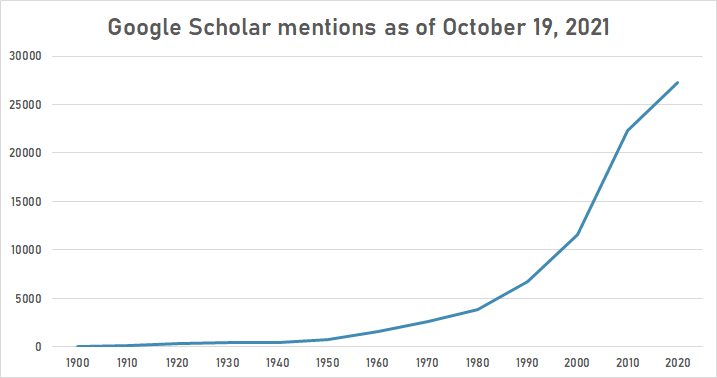

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 19, 2021.

| Year | "parasitology" |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 37 |

| 1910 | 164 |

| 1920 | 308 |

| 1930 | 409 |

| 1940 | 474 |

| 1950 | 800 |

| 1960 | 1,580 |

| 1970 | 2,620 |

| 1980 | 3,870 |

| 1990 | 6,730 |

| 2000 | 11,600 |

| 2010 | 22,300 |

| 2020 | 27,300 |

Google Trends

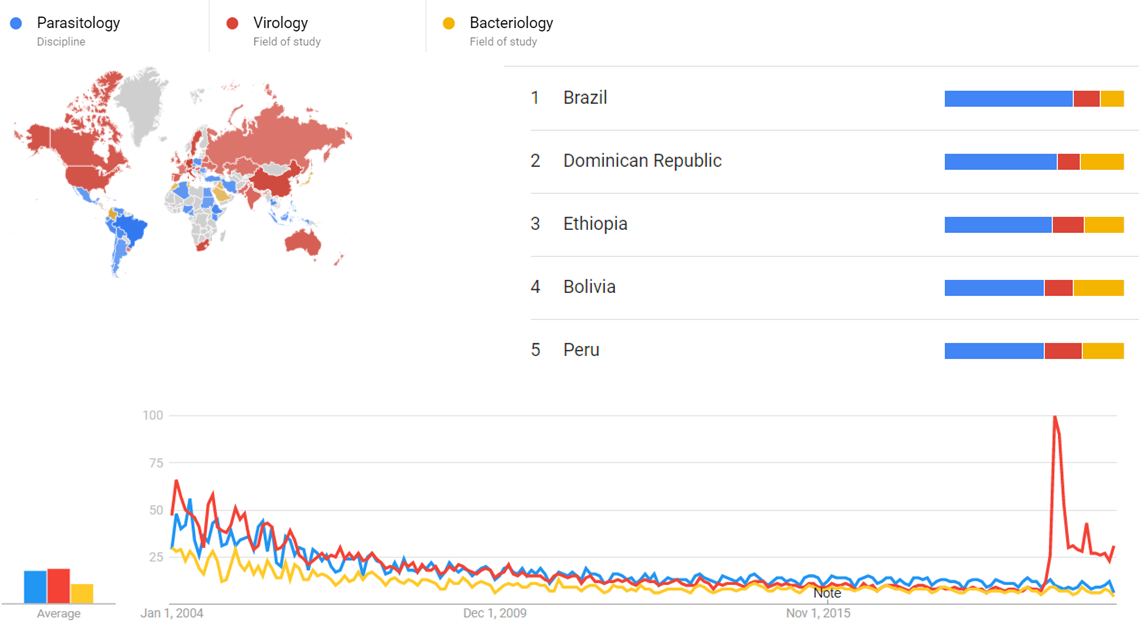

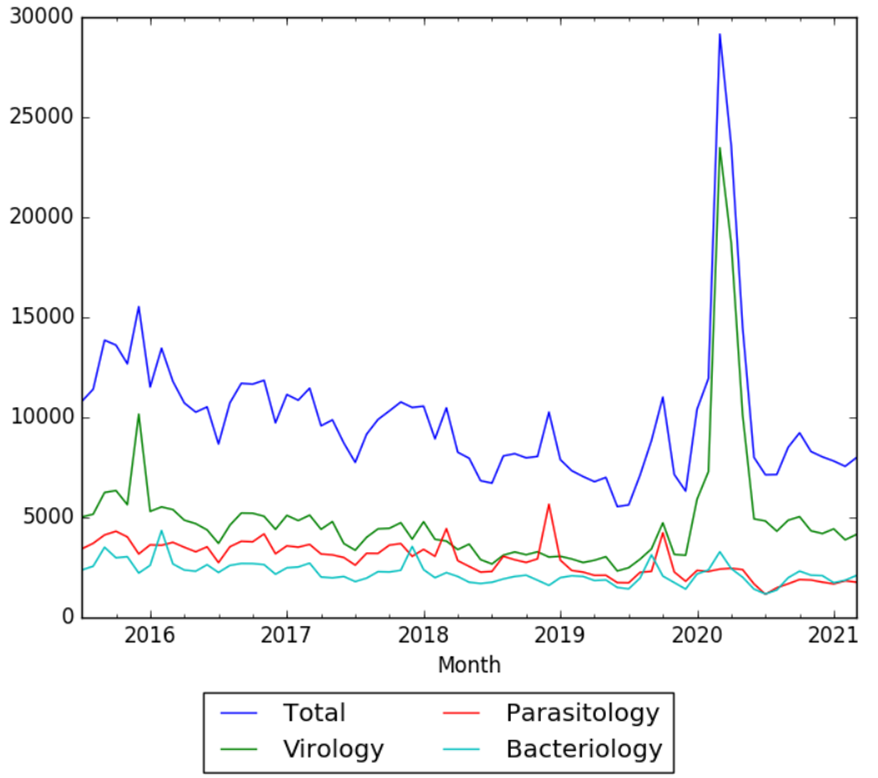

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Virology (Field of study), Parasitology (Field of study), and Bacteriology (Field of study), from January 2004 to Month 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[110]

Google Ngram Viewer

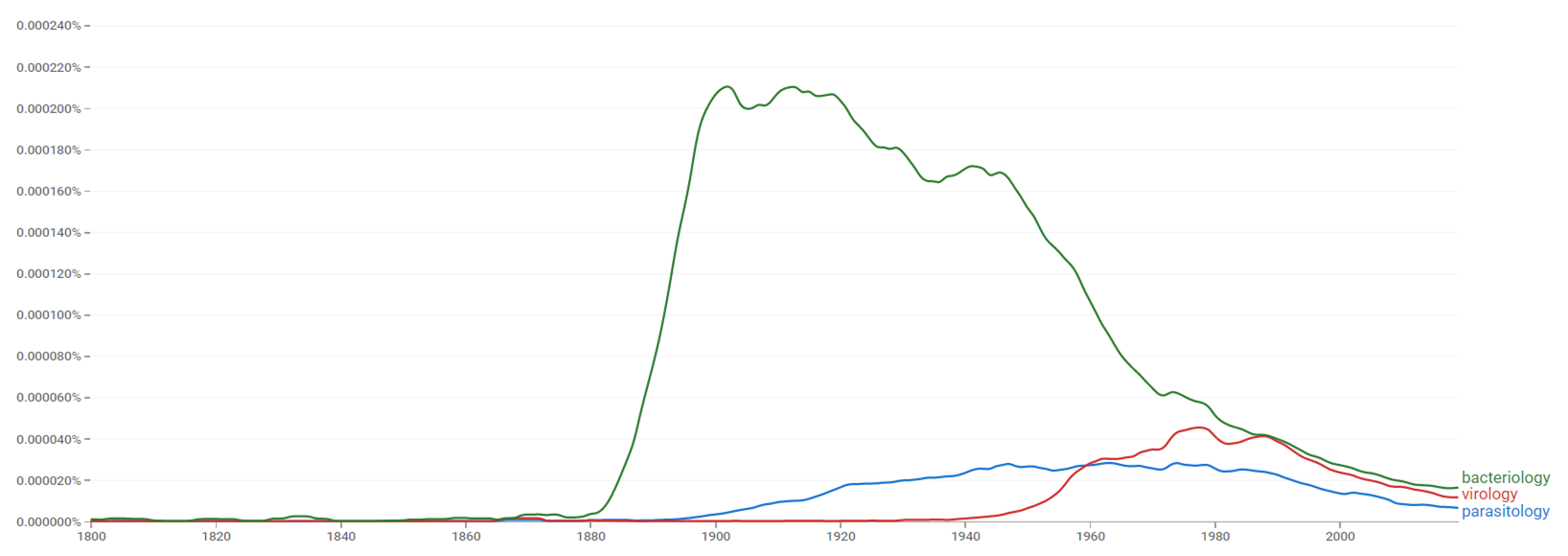

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for bacteriology, virology and parasitology, from 1800 to 2019.[111]

Wikipedia Views

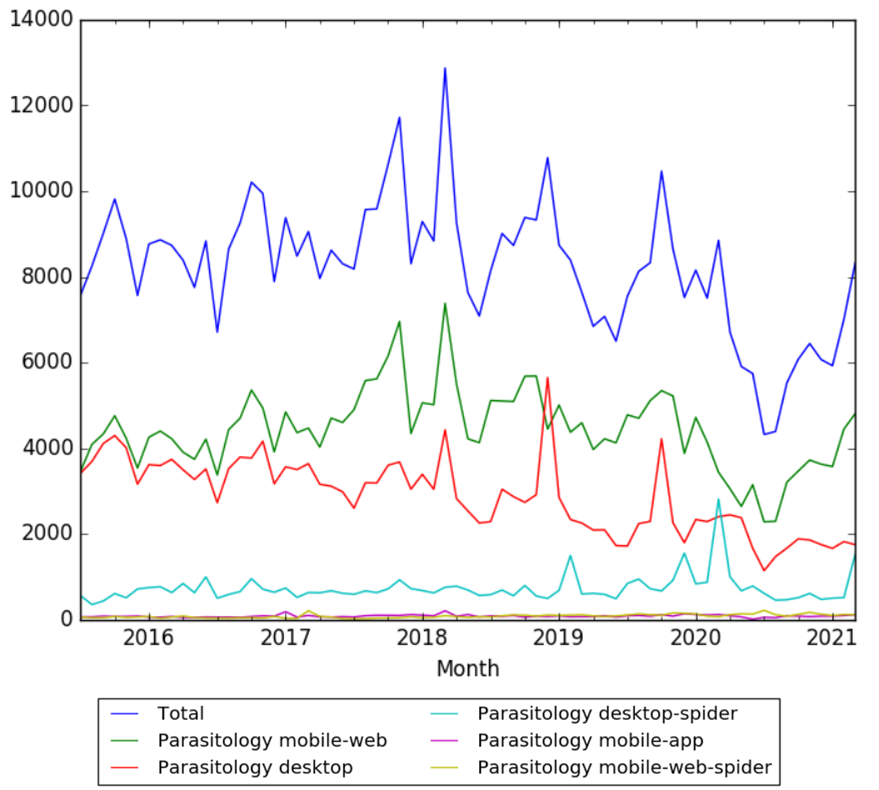

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article parasitology, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to February 2021.[112]

The comparative chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia articles parasitology, virology and bacteriology, on desktop, from July 2015 to February 2021.[113]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 1.48 1.49 1.50 1.51 1.52 1.53 1.54 1.55 Cox, F. E. G. "History of Human Parasitology". doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.595-612.2002. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Timeline of Microbiology". timelines.ws. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 3.33 3.34 3.35 3.36 3.37 3.38 3.39 3.40 3.41 3.42 Mehlhorn, Heinz; Tan, Kevin S. W.; Yoshikawa, Hisao. Ascaris%2C%20Enterobius%2C%20tapeworms&f=false Blastocystis: Pathogen or Passenger?: An Evaluation of 101 Years of Research.

- ↑ Prioreschi, Plinio. A History of Medicine: Renaissance medicine.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sun, Tsieh. Progress in Clinical Parasitology, Volume 4.

- ↑ Tropical Dermatology (Roberto Arenas, Roberto Estrada ed.).

- ↑ "History of Human Parasitology". studfiles.net. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Ridley, John W. Parasitology for Medical and Clinical Laboratory Professionals.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ridley, John W. Parasitology for Medical and Clinical Laboratory Professionals.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Foster, C Stephen; Vitale, Albert T. Diagnosis & Treatment of Uveitis.

- ↑ Brisola Marcondes, Carlos. Arthropod Borne Diseases.

- ↑ Magill, Alan J. Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease,Expert Consult - Online and Print,9: Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 Sangüeza, Omar P; Bravo, Francisco. Dermatopathology of Tropical Diseases: Pathology and Clinical Correlations.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 Turgut, Mehmet. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment.

- ↑ "AFIP index". Afip.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Medical and Surgical Reporter, Volume 9.

- ↑ "Complications of Central Nervous System Hydatid Disease". karger.com. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Control of Human Parasitic Diseases.

- ↑ Abuladze, Konstantin Ivanovich. Taeniata of animals and man and diseases caused by them.

- ↑ Sridharan, Srihari; Narayana, Jagan; Chidambaram, Kalyanasundarabharathi; Jayachandiran, Anand Prasath. "Primary paraspinal hydatidosis causing acute paraplegia". Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Turgut, Mehmet. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment.

- ↑ Campbell, William. Trichinella and Trichinosis.

- ↑ Parasites of the Colder Climates (Hannah Akuffo, Inger Ljungstr”m, Ewert Linder, Mats Wahlgren ed.).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Dobson, Mary. Murderous Contagion: A Human History of Disease.

- ↑ Mostofi, F. K. Bilharziasis: International Academy of Pathology · Special Monograph.

- ↑ "LOIASIS IN UNANI MEDICINE" (PDF). journalagent.com. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ Cobo, Fernando. Imported Infectious Diseases: The Impact in Developed Countries.

- ↑ "Chylothorax, Chyluria, Elephantiasis, Pallor". symptoma.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ↑ Ridley, John W. Parasitology for Medical and Clinical Laboratory Professionals.

- ↑ Turgut, Mehmet. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment.

- ↑ Cheng, Thomas C. General Parasitology.

- ↑ Peart, Olive. Mammography and Breast Imaging PREP: Program Review and Exam Prep.

- ↑ Dittmar, Thomas; Zaenker, Kurt S.; Schmidt, Axel. Infection and Inflammation: Impacts on Oncogenesis.

- ↑ Public Health and Infectious Diseases (Jeffrey Griffiths, James H. Maguire, Kristian Heggenhougen, Stella R. Quah ed.).

- ↑ Advances in Parasitology, Volume 63.

- ↑ Cockerham, William C. International Encyclopedia of Public Health.

- ↑ BARAN MANDAL, FATIK. HUMAN PARASITOLOGY.

- ↑ Bernhard, Carl Gustaf; Crawford, E.; Sörbom, P. Science, Technology & Society in the Time of Alfred Nobel: Nobel Symposium 52 Held at Björkborn, Karlskoga, Sweden, 17-22 August 1981.

- ↑ The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, Volumes 32-33. Government Printer, South Africa, 1965.

- ↑ Materialy 3-i Nauchnoi Konferentsii Po Infektssionnym i Invazionnym Zabolevaniyam Sel'skokhozyaistvennykh Zhivotnykh. National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. and the Department of Agriculture, U.S.A., 1962.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Emergence of Polycystic Neotropical Echinococcosis". doi:10.3201/eid1402.070742.

- ↑ Turgut, Mehmet. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment.

- ↑ Katz, M.; Despommier, D.D.; Gwadz, R.W. Parasitic Diseases.

- ↑ Cobo, Fernando. Imported Infectious Diseases: The Impact in Developed Countries.

- ↑ Franco-Paredes, Carlos; Santos-Preciado, José Ignacio. Neglected Tropical Diseases - Latin America and the Caribbean.

- ↑ "Dracunculus". tititudorancea.com. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Lise; Hardy, Anne. Prevention and Cure: The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine : a 20th Century Quest for Global Public Health.

- ↑ Gleick, Peter H. The World's Water 1998-1999: The Biennial Report On Freshwater Resources.

- ↑ BARAN MANDAL, FATIK. BIOLOGY OF NON-CHORDATES.

- ↑ Haubrich, William S.; Schaffner, Fenton; Bockus, Henry L. Bockus Gastroenterology, Volume 4.

- ↑ Bruschi, Fabrizio. Frontiers in Parasitology, Volume 2.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Bruschi, Fabrizio. Helminth Infections and their Impact on Global Public Health.

- ↑ Palmer, Philip E.S.; Reeder, Maurice M. The Imaging of Tropical Diseases: With Epidemiological, Pathological and Clinical Correlation, Volume 2.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Ridley, John W. Parasitology for Medical and Clinical Laboratory Professionals.

- ↑ Diaz, James H. "Paragonimiasis Acquired in the United States: Native and Nonnative Species". PMC 3719489

. PMID 23824370. doi:10.1128/CMR.00103-12.

. PMID 23824370. doi:10.1128/CMR.00103-12.

- ↑ Water and Health (Prati Pal Singh, Vinod Sharma ed.).

- ↑ Bulletin, Volumes 11-15. Vermont. State Board of Health.

- ↑ Vaughan, Victor Clarence; Vaughan, Henry Frieze; Palmer, George Truman. Epidemiology and public health, a text and reference book for physicians, medical students and health workers...

- ↑ Ridley, John W. Parasitology for Medical and Clinical Laboratory Professionals.

- ↑ Sebastian, Anton. A Dictionary of the History of Medicine.

- ↑ Esch, Gerald. Parasites and Infectious Disease: Discovery by Serendipity and Otherwise.

- ↑ Baker, J. R.; Muller, R.; Rollinson, D. Advances in Parasitology.

- ↑ "Annals of tropical medicine and parasitology". archive.org. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Advances in Parasitology, Volume 100.

- ↑ Page, Walter H. (September 1912). "The Hookworm And Civilization: The Work Of The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission In The Souther States". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. Vol. XXIV. pp. 504–518. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ Grove, David. Tapeworms, Lice, and Prions: A Compendium of Unpleasant Infections.

- ↑ Cox, F E G. "History of Human Parasitology".

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Tyring, Steven K; Lupi, Omar; Hengge, Ulrich R. Tropical Dermatology E-Book.

- ↑ Ghosh, Sougata. Paniker's Textbook of Medical Parasitology.

- ↑ Tyring, Steven K; Lupi, Omar; Hengge, Ulrich R. Tropical Dermatology E-Book.

- ↑ "The Journal of Parasitology". jstor.org. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Franco-Paredes, Carlos; Santos-Preciado, José Ignacio. Neglected Tropical Diseases - Latin America and the Caribbean.

- ↑ Sangüeza, Omar P; Bravo, Francisco. Dermatopathology of Tropical Diseases: Pathology and Clinical Correlations.

- ↑ MANDAL, FATIK BARAN. HUMAN PARASITOLOGY.

- ↑ Gillespie, Stephen; Pearson, Richard D. Principles and Practice of Clinical Parasitology.

- ↑ Rubin, Robert H.; Young, Lowell S. Clinical Approach to Infection in the Compromised Host.

- ↑ Farrar, Jeremy; Hotez, Peter J; Junghanss, Thomas; Kang, Gagandeep; Lalloo, David; White, Nicholas J. Manson's Tropical Diseases E-Book.

- ↑ Kassirsky, I. A.; Plotnikov, N. N. Diseases of Warm Lands: A Clinical Manual.

- ↑ Brisola Marcondes, Carlos. Arthropod Borne Diseases.

- ↑ Grove, David. Tapeworms, Lice, and Prions: A Compendium of Unpleasant Infections.

- ↑ "Annales de parasitologie humaine et comparee". catalyst.library.jhu.edu. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "The American Society of Parasitologists: A Short History". jstor.org. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Turgut, Mehmet. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment.

- ↑ "DEW, HAROLD ROBERT". sydney.edu.au. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Dew, Sir Harold Robert (1891–1962)". adb.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ Sangüeza, Omar P; Bravo, Francisco. Dermatopathology of Tropical Diseases: Pathology and Clinical Correlations.

- ↑ Helminthological Abstracts, Volume 25. Institute of Agricultural Parasitology.

- ↑ "Experimental parasitology".

- ↑ "Société française de parasitologie". data.bnf.fr. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Stoll NR (August 1962). "On endemic hookworm, where do we stand today?". Exp. Parasitol. 12 (4): 241–52. PMID 13917420. doi:10.1016/0014-4894(62)90072-3.

- ↑ Esch, Gerald. Parasites and Infectious Disease: Discovery by Serendipity and Otherwise.

- ↑ The Laboratory Digest, Volumes 28-29.

- ↑ Hotez, Peter J; Bethony, Jeff; Bottazzi, Maria Elena; Brooker, Simon; Buss, Paulo. "Hookworm: "The Great Infection of Mankind"". PMC 1069663

. PMID 15783256. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020067.

. PMID 15783256. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020067.

- ↑ "Advances in Parasitology, Volume 65". elsevier.com. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "European Federation of Parasitologists". eurofedpar.eu. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Vickerman, K. "Antigenic variation in trypanosomes.". PMID 661969.

- ↑ Advances in Parasitology, Volume 17.

- ↑ Advances in Parasitology (J. R. Baker, R. Muller, D. Rollinson ed.).

- ↑ "International journal for parasitology.". trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 100.3 parvum&f=false Opportunistic Protozoa in Humans.

- ↑ parvum&f=false Cryptosporidium: From Molecules to Disease (R.C.A. Thompson, A. Armson, U.M. Ryan ed.).

- ↑ Sangüeza, Omar P; Bravo, Francisco. Dermatopathology of Tropical Diseases: Pathology and Clinical Correlations.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize for medicine for drugs that have benefited billions". newscientist.com. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Systematic Parasitology". journals.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "School Deworming". Public Health at a Glance. World Bank. 2003.

- ↑ Hawdon JM, Hotez PJ (October 1996). "Hookworm: developmental biology of the infectious process". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6 (5): 618–23. PMID 8939719. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80092-X.

- ↑ "Parasites & Vectors". Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Webster, Bonnie L.; Diaw, Oumar T.; Seye, Mohmoudane M.; Webster, Joanne P.; Rollinson, David. "Introgressive Hybridization of Schistosoma haematobium Group Species in Senegal: Species Barrier Break Down between Ruminant and Human Schistosomes". Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMC 5055577

. PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6.

. PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6.

- ↑ "Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology". Google Trends. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ "Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology". books.google.com. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ "Parasitology". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ "Virology, Parasitology, Bacteriology". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 3 April 2021.