Difference between revisions of "Timeline of genetic engineering in humans"

(→Visual data) |

(→Visual data) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

For a full history of the biotechnologial context in which that happened, see the Genetic Literacy Project's timeline, [https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2017/07/18/biotechnology-timeline-humans-manipulating-genes-since-dawn-civilization/ Biotechnology timeline: Humans have manipulated genes since the ‘dawn of civilization’]. For a timeline of the CRISPR technology, see [[Timeline of CRISPR]]. For a timeline on genetics engineering in general, see [[Timeline of genetic engineering]]. | For a full history of the biotechnologial context in which that happened, see the Genetic Literacy Project's timeline, [https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2017/07/18/biotechnology-timeline-humans-manipulating-genes-since-dawn-civilization/ Biotechnology timeline: Humans have manipulated genes since the ‘dawn of civilization’]. For a timeline of the CRISPR technology, see [[Timeline of CRISPR]]. For a timeline on genetics engineering in general, see [[Timeline of genetic engineering]]. | ||

| − | == | + | == Numerical and visual data == |

| + | |||

| + | === Mentions on Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 30, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! genetic engineering | ||

| + | ! genetic engineering in humans | ||

| + | ! gene therapy | ||

| + | ! human genome project | ||

| + | ! human clone | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || || || 28,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || || || 10,700 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || || || 41,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || || || 41,400 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || || || 144,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2002 || || || 174,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004 || || || 256,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || || || 315,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || || || 401,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || || || 455,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || || || 560,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2014 || || || 504,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2016 || || || 377,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017 || || || 343,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || || || 228,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2019 || || || 145,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || || || 110,000 || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:xxx|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

=== Google Trends === | === Google Trends === | ||

The image below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Genetic engineering in humans (Search term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Genetic engineering in humans |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=Genetic%20engineering%20in%20humans |website=Google Trends |access-date=23 February 2021}}</ref> | The image below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Genetic engineering in humans (Search term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Genetic engineering in humans |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=Genetic%20engineering%20in%20humans |website=Google Trends |access-date=23 February 2021}}</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:Genetic engineering in humans gt.jpg|thumb|center| | + | [[File:Genetic engineering in humans gt.jpg|thumb|center|600px]] |

=== Google Ngram Viewer === | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

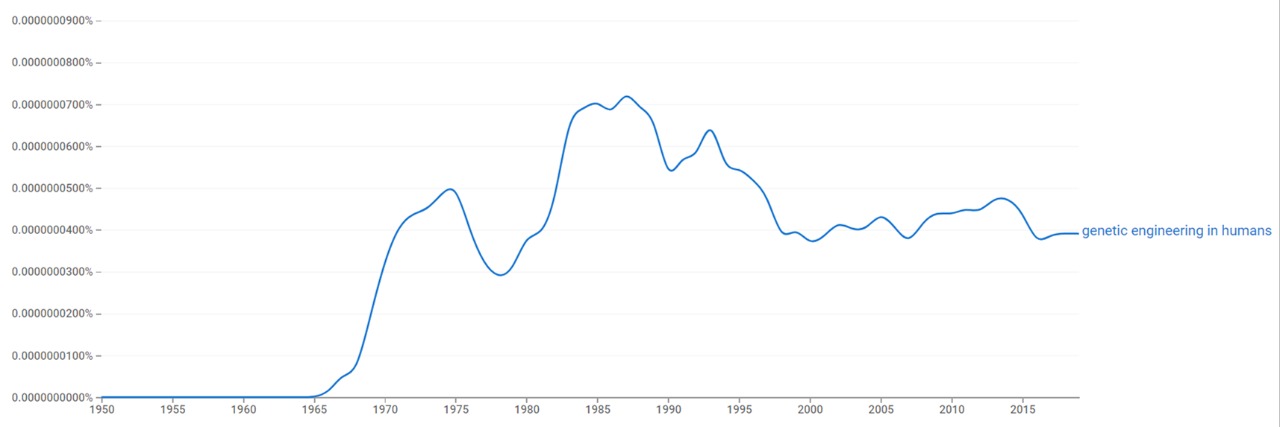

The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Genetic engineering in humans from 1950 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Genetic engineering in humans |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Genetic+engineering+in+humans&year_start=1950&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&case_insensitive=true&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cgenetic%20engineering%20in%20humans%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cgenetic%20engineering%20in%20humans%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=23 February 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Genetic engineering in humans from 1950 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Genetic engineering in humans |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Genetic+engineering+in+humans&year_start=1950&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&case_insensitive=true&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cgenetic%20engineering%20in%20humans%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cgenetic%20engineering%20in%20humans%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=23 February 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:Genetic engineering in humans ngram.jpg|thumb|center| | + | [[File:Genetic engineering in humans ngram.jpg|thumb|center|700px]] |

=== Wikipedia Views === | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

Revision as of 12:34, 30 May 2021

This is a timeline of genetic engineering in humans.

There are some evidence that humans might have self-domesticated, which could be seen as a form of genetic engineering.[1]

However, actual genetic engineering started in the 20th century. The timeline below details related milestones.

For a full history of the biotechnologial context in which that happened, see the Genetic Literacy Project's timeline, Biotechnology timeline: Humans have manipulated genes since the ‘dawn of civilization’. For a timeline of the CRISPR technology, see Timeline of CRISPR. For a timeline on genetics engineering in general, see Timeline of genetic engineering.

Contents

Numerical and visual data

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 30, 2021.

| Year | genetic engineering | genetic engineering in humans | gene therapy | human genome project | human clone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 28,000 | |||||||||

| 1985 | 10,700 | |||||||||

| 1990 | 41,000 | |||||||||

| 1995 | 41,400 | |||||||||

| 2000 | 144,000 | |||||||||

| 2002 | 174,000 | |||||||||

| 2004 | 256,000 | |||||||||

| 2006 | 315,000 | |||||||||

| 2008 | 401,000 | |||||||||

| 2010 | 455,000 | |||||||||

| 2012 | 560,000 | |||||||||

| 2014 | 504,000 | |||||||||

| 2016 | 377,000 | |||||||||

| 2017 | 343,000 | |||||||||

| 2018 | 228,000 | |||||||||

| 2019 | 145,000 | |||||||||

| 2020 | 110,000 |

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data for Genetic engineering in humans (Search term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[2]

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Genetic engineering in humans from 1950 to 2019.[3]

Wikipedia Views

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1978 | July 25 | For the first time, a human is born through in vitro fertilization.[4] |

| 1983 | For the first time, a human gets a pregnancy derived from a cryopreserved human embryo (but was aborted naturally at ten weeks of gestation).[5] | |

| 1984 | The first human derived from a cryopreserved human embryo is born.[5] | |

| 1990s | China starts to do widespread prenatal testing for birth defects with ultrasound.[6] | |

| 1990 | The first human that had received a preimplantation genetic diagnosis is born.[7] | |

| 1990 | Sept. 14 | For the first time, a human receives a gene therapy. They get white blood cells extracted from them, injected with normal genes for making adenosine deaminase, and then inserted again into them.[8] |

| 1990 | Oct. 1 | The Human Genome Project to map the entire human genome is officially launched.[9] |

| 1997 | June | The world's first genetically modified human is born. They receive a ooplasmic transfer, which consist in taking the contents of a donor egg from a fertile female and injecting it into the egg of an infertile female along with the fertilizing sperm from their mate.[10] |

| 1998 | November | The first hybrid human clone is created in November 1998, by Advanced Cell Technology. It is created using Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) - a nucleus is taken from a cell of a male's leg and inserted into a cow's egg from which the nucleus is removed, and the hybrid cell is cultured, and developed into an embryo. The embryo is destroyed after 12 days.[11] |

| 2000 | June 26 | The Human Genome Project and Celera Genomics announce the completion of the first draft of the human genome.[12] |

| 2003 | BGI Shenzhen, in China, collects DNA samples from 2,000 of the world's smartest people. The screening includes sending a CV, a list of publications, standardized-test scores, where one went to college, etc. They sequence the entire genomes and attempt to identify the alleles which correlate with intelligence. This could lead to embryo screening increasing intelligence by 5 to 15 IQ points.[6] | |

| 2008 | January | Researchers at the company Stemagen announce that they successfully created the first five mature human embryos using SCNT. Each embryo was created by taking a nucleus from a skin cell (donated by Wood and a colleague) and inserting it into a human egg from which the nucleus had been removed. The embryos would develop only to the blastocyst stage.[13][14] |

| 2013 | Embryonic stem cells are created using SCNT for the first time. Four embryonic stem cell lines from human fetal somatic cells are derived from those blastocysts. All four lines are derived using oocytes from the same donor, ensuring that all mitochondrial DNA inherited are identical.[15] A year later, a team led by Robert Lanza at Advanced Cell Technology reported that they had replicated Mitalipov's results and further demonstrated the effectiveness by cloning adult cells using SCNT.[16] | |

| 2015 | April 18 | Researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou publish a paper on their attempt to use the CRISPR/Cas-9 system to edit the hemoglobin-B gene (HBB) in 86 non-viable human embryos. [17] Two days later, 54 embryos would survive, only 4 would have the desired genetic changes, and all 4 would be mosaic (meaning only some cells would have the desired changes), and they would contain a lot of unintended mutations.[17] |

| 2016 | Nov. 15 | For the first time, CRISPR gene-editing is tested in a human.[18] |

| 2017 | For the first time in the United States, there's an attempt of using CRISPR to genetically modify human embryos.[19] | |

| 2018 | Nov. 25 | A Chinese researcher of Shenzhen claims that he helped make the first genetically edited humans. [20] The humans are twins named Lulu and Nana. [21]. They are claimed to have been born a few weeks before he announced it.[20] The researcher's stated goal is to make sure the humans would have the ability to resist an HIV infection, a trait few people naturally have.[20] He gave official notice of his work on November 8, 2018 on a Chinese registry of clinical trials.[20]

One-off target edit was found before implementing the embryo, but wasn’t confirmed when the humans were sequenced after birth.[21] Only some of the cells of the early-stage embryo were successfully edited, and one edit resulted in a CCR5 protein missing five amino acids, so it’s unclear whether they will actually be resistant to HIV.[21] China’s vice minister of science and technology, Xu Nanping, said the effort “crossed the line of morality and ethics and was shocking and unacceptable.”[22] The researcher is currently in prison.[23] |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by Mati.

References

- ↑ "CARTA: Domestication and Human Evolution - Richard Wrangham: Did Homo sapiens Self-Domesticate?". Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Genetic engineering in humans". Google Trends. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ "Genetic engineering in humans". books.google.com. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ Weule, Genelle (24 July 2018). "The first IVF baby was born 40 years ago today". ABC News. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Trounson A, Leeton J, Besanko M, Wood C, Conti A (March 1983). "Pregnancy established in an infertile patient after transfer of a donated embryo fertilised in vitro". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 286 (6368): 835–8. PMC 1547212

. PMID 6403104. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6368.835.

. PMID 6403104. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6368.835.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "China Is Engineering Genius Babies - VICE". web.archive.org. 2019-09-09. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ↑ Handyside AH, Lesko JG, Tarín JJ, Winston RM, Hughes MR (September 1992). "Birth of a normal girl after in vitro fertilization and preimplantation diagnostic testing for cystic fibrosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (13): 905–9. PMID 1381054. doi:10.1056/NEJM199209243271301.

- ↑ "Gene Therapy".

- ↑ "About NHGRI: A Brief History and Timeline".

- ↑ "World's first genetically altered babies born". CNN.com. 2001-05-05.

- ↑ "Details of hybrid clone revealed". BBC News. June 18, 1999. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ↑ "International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium Announces "Working Draft" of Human Genome". June 2000. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ↑ Rick Weiss for the Washington Post January 18, 2008 Mature Human Embryos Created From Adult Skin Cells

- ↑ French AJ, Adams CA, Anderson LS, Kitchen JR, Hughes MR, Wood SH (2008). "Development of human cloned blastocysts following somatic cell nuclear transfer with adult fibroblasts". Stem Cells. 26 (2): 485–93. PMID 18202077. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0252.

- ↑ Trounson A, DeWitt ND (2013). "Pluripotent stem cells from cloned human embryos: success at long last". Cell Stem Cell. 12 (6): 636–8. PMID 23746970. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.022.

- ↑ Chung YG, Eum JH, Lee JE, Shim SH, Sepilian V, Hong SW, Lee Y, Treff NR, Choi YH, Kimbrel EA, Dittman RE, Lanza R, Lee DR (2014). "Human somatic cell nuclear transfer using adult cells". Cell Stem Cell. 14 (6): 777–80. PMID 24746675. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.015.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Chinese paper on embryo engineering splits scientific community". 2015-04-24.

- ↑ "CRISPR gene-editing tested in a person for the first time". 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ↑ "First Human Embryos Edited in U.S.". 2017-07-26.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 "Chinese researcher claims birth of first gene-edited babies — twin girls". 2018-11-25.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Amid uproar, Chinese scientist defends creating gene-edited babies". 2018-11-28.

- ↑ "Despite CRISPR baby controversy, Harvard University will begin gene-editing sperm". 2018-11-29.

- ↑ Samuel, Sigal (2020-01-13). "19 big predictions about 2020, from Trump's reelection to Brexit". Vox. Retrieved 2020-02-29.