Timeline of fact-checking

From Timelines

This timeline covers independent fact-checking operations, as well as key events that shaped the perception and application of fact-checking.

Contents

Numerical and visual data

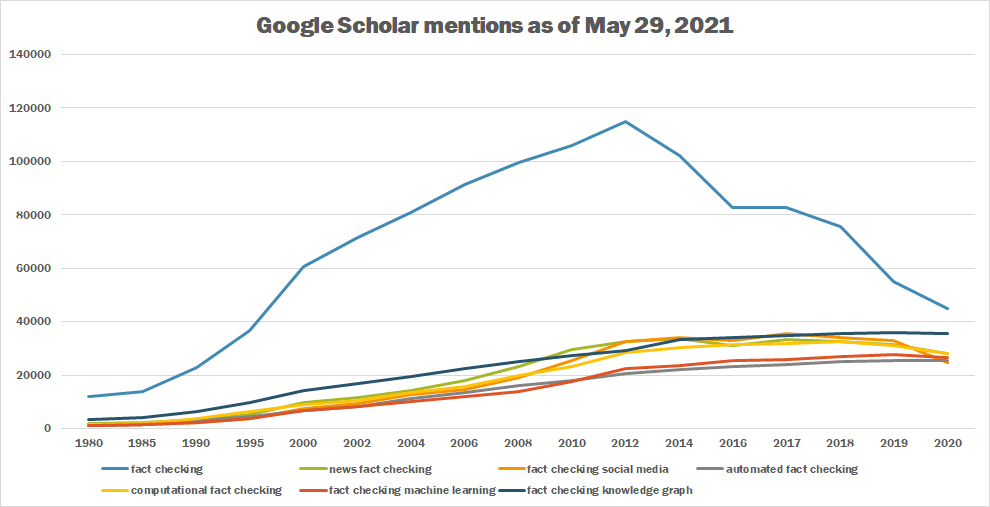

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 20, 2021.

| Year | fact checking | news fact checking | fact checking social media | automated fact checking | computational fact checking | fact checking machine learning | fact checking knowledge graph |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11,800 | 1,780 | 1,250 | 1,050 | 1,310 | 936 | 3,510 |

| 1985 | 13,900 | 2,180 | 1,450 | 1,420 | 1,810 | 1,310 | 4,000 |

| 1990 | 22,900 | 3,400 | 2,170 | 2,850 | 3,840 | 2,340 | 6,330 |

| 1995 | 36,500 | 5,100 | 3,790 | 4,300 | 6,340 | 3,540 | 9,620 |

| 2000 | 60,500 | 9,840 | 7,390 | 6,840 | 8,890 | 6,900 | 14,100 |

| 2002 | 71,600 | 11,700 | 9,490 | 8,230 | 10,400 | 8,200 | 16,800 |

| 2004 | 80,900 | 14,300 | 12,600 | 11,100 | 13,600 | 10,200 | 19,500 |

| 2006 | 91,200 | 18,100 | 14,700 | 13,600 | 15,600 | 11,800 | 22,300 |

| 2008 | 99,700 | 23,100 | 18,900 | 16,000 | 20,000 | 14,000 | 24,900 |

| 2010 | 106,000 | 29,400 | 25,600 | 18,000 | 23,300 | 17,600 | 27,400 |

| 2012 | 115,000 | 32,700 | 32,400 | 20,700 | 28,400 | 22,300 | 29,000 |

| 2014 | 102,000 | 33,500 | 34,100 | 21,900 | 30,400 | 23,700 | 33,400 |

| 2016 | 82,800 | 30,900 | 32,800 | 23,300 | 31,600 | 25,600 | 34,200 |

| 2017 | 82,900 | 33,300 | 35,500 | 23,800 | 31,900 | 25,800 | 34,800 |

| 2018 | 75,600 | 32,400 | 34,000 | 25,100 | 32,400 | 27,000 | 35,500 |

| 2019 | 55,100 | 31,300 | 32,900 | 25,400 | 31,000 | 27,500 | 35,800 |

| 2020 | 44,900 | 28,100 | 24,700 | 25,400 | 28,200 | 26,500 | 35,700 |

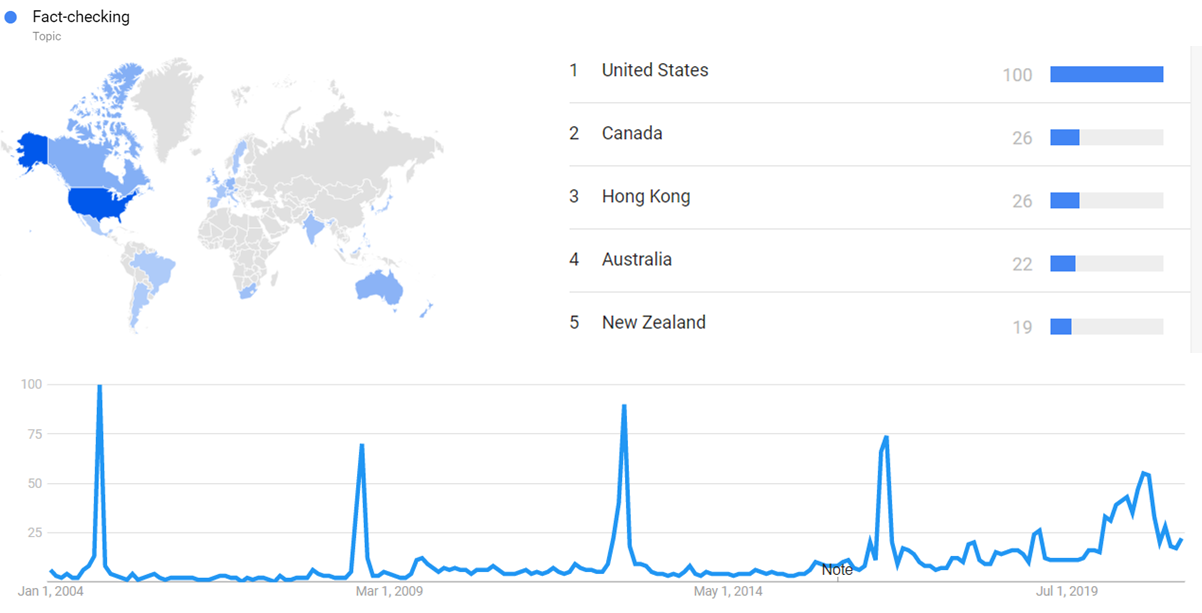

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Fact-checking (Topic), from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[1]

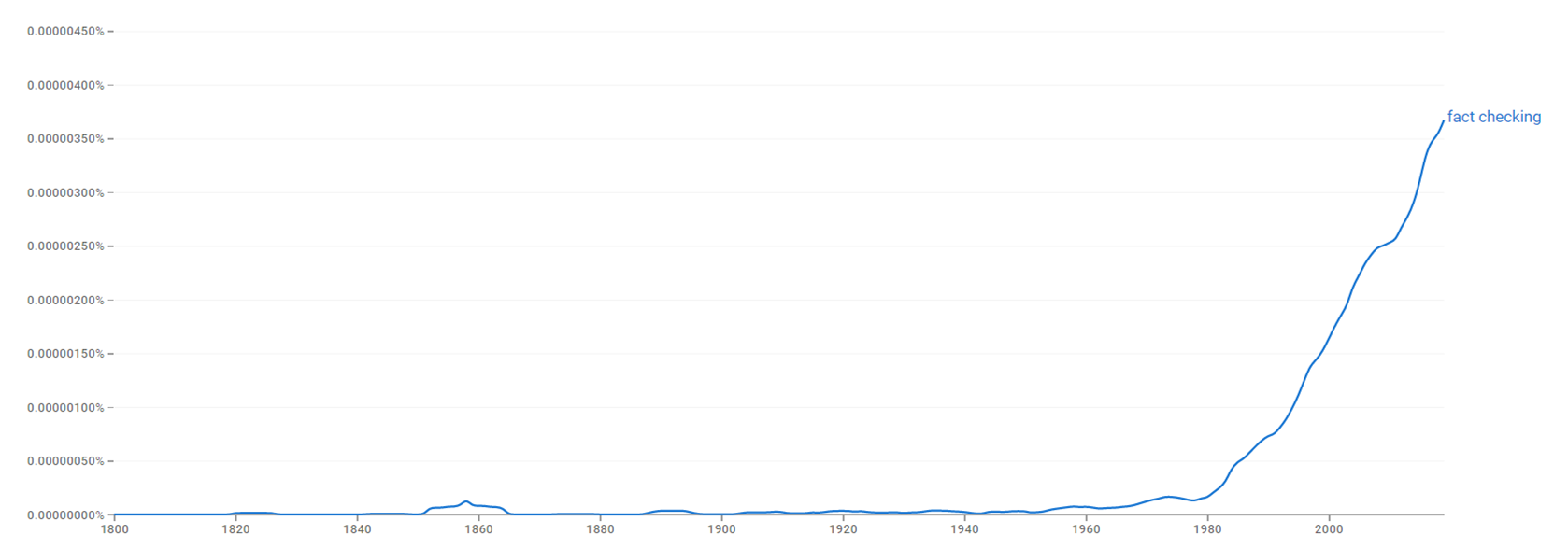

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for fact checking, from 1800 to 2019.[2]

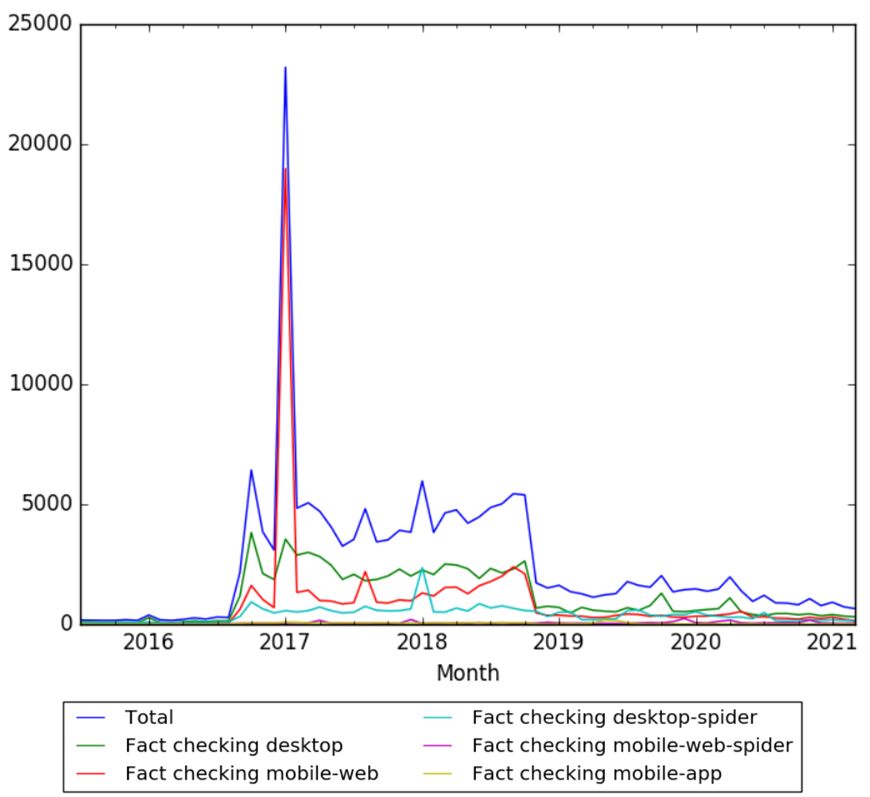

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Fact checking, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to February 2021.[3]

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date (if available) | Event type | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | Internal fact-checking operations | TIME Magazine, around the time of its first issue, hires Nancy Ford for a role that would include verifying basic dates, names and facts in completed TIME articles. This would mark the beginning of the magazine's fact-checking operation, which would hire a handful of people, all women.[4] | United States (but some content covers global topics) | |

| 1927 | Internal fact-checking operations | The New Yorker begins rigorous fact-checking, two years after the magazine's launch in 1925.[4] | United States (but some content covers global topics) | |

| 1933 | Internal fact-checking operations | Newsweek begins rigorous fact-checking, following the precedent of TIME and the New Yorker.[4] | United States (but some content covers global topics) | |

| 1995 | Fact-checking website launch | Snopes.com is founded by couple David and Barbara Mikkelson, initially as a website to debunk urban legends, though it subsequently expands to covering the factual accuracy of popular stories or claims.[5] The website is an outgrowth of David Mikkelson's work with username 'snopes' in the Usenet newsgroup alt.folklore.urban.[6] | Global (though more focused on the United States) | |

| 2003 | December | Fact-checking website launch | factcheck.org is launched as a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center by Brooks Jackson.[7] The first fact-check appears to have been published on December 4, 2003.[8] | United States |

| 2007 | August | Fact-checking website launch | PolitiFact.com launches as a project operated by Tampa Bay Times, in which reporters and editors from the Times and affiliated media fact check statements by members of Congress, the White House, lobbyists and interest groups. The website publishes original statements as well as evaluations along a Truth-o-Meter.[9] | United States |

| 2007 | September 19 | Fact-checking website launch | The Washington Post launches The Fact Checker, a blog by veteran journalist Glenn Kessler that rates statements by politicians according to their accuracy, with the rating ranging from one to four Pinocchios (more Pinocchios means a bigger lie).[10] The initial launch is for the purpose of the 2008 Presidential Election in the United States | United States |

| 2010 | Fact-checking website launch | Full Fact, a website devoted to fact-checking (and the eponymous nonprofit) launches.[11] | United Kingdom | |

| 2010 | January | Fact-checking website expansion | PolitiFact expands to its second newspaper, the Cox Enterprises–owned Austin American-Statesman in Austin, Texas. The subproject, PolitiFact Texas, focuses on fact-checking Texas local news. | United States (Texas) |

| 2010 | March | Fact-checking website expansion | PolitiFact expands to its third newspaper, The Miami Herald in Florida. The subject, PolitiFact Florida, focuses on Florida local news. | United States (Florida) |

| 2011 | January 9 | Fact-checking website revival | The Washington Post revives and makes permanent Glenn Kessler's blog, The Fact Checker, that was originally piloted during the 2008 Presidential elections | United States |

| 2014 | January | Fact-checking website launch | Correctiv (stylized CORRECT!V), a fact-checking website in Germany, launches.[12][13] | Germany |

| 2015 | September 21 | Fact-checking network | The International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) is launched under the auspices of the Poynter Institute, in recognition of and in order to facilitate better standards and cooperation between numerous fact-checking initiatives. Alexios Mantzarlis is the first director and editor of IFCN.[14][15][16] | Global |

| 2016 | September 17 | Fact-checking automation | Google gives a 50,000 euro grant to Full Fact as part of its Digital News Initiative (DNI) to help Full Fact automate some of its fact-checking tools. The two tools, slated for completion by the end of 2017, are Trends and Robocheck. Trends will detect how widely a claim has circulated online, while Robocheck will attempt to give real-time information on conclusions about the claims.[17] | United Kingdom |

| 2016 | December 15 | Social media partnership | Facebook announces a set of news feed updates to combat the problem of fake news and hoaxes. These include more streamlining for users reporting fake news, a partnership with signatory organizations to Poynter’s International Fact Checking Code of Principles to examine items reported as fake, learning from lower share rates for people who view the article that the item might be fake, and warnings to users when they share news that is disputed or possibly fake.[18][19][20][21] | Global |

| 2017 | January | Alleged fake news | On January 3, Breitbart News publishes a story with the title "1,000-Man Mob Attack Police, Set Germany’s Oldest Church Alight on New Year’s Eve".[22] The accuracy of the story is contested by a number of outlets including the Washington Post.[23] It leads to a renewed interest among German politicians in tackling the "fake news" problem, along with suspicions of interference from Russia.[24][25][26] Breitbart News continues to defend its coverage and attacks the use of the "fake news" label for its reporting.[27][28] | Germany |

| 2017 | January 30 | Government investigation | The Culture, Media and Sports Committee of the United Kingdom Parliament launches an investigation into "fake news".[29][30] The Committee would conclude its work by May 3, 2017, at which point it would cease to exist due to the dissolution of Parliament.[31] | United Kingdom |

References

- ↑ "Fact-checking". Google Trends. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ "fact checking". books.google.com. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ "Fact checking". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Fabry, Merrill (August 24, 2017). "Here's How the First Fact-Checkers Were Able to Do Their Jobs Before the Internet". TIME Magazine. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Seipp, Cathy (July 21, 2004). "Where Urban Legends Fall". National Review. Archived from the original on July 23, 2004. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Porter, David (2013). "Usenet Communities and the Cultural Politics of Information". Internet Culture. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-135-20904-9. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

The two most notorious trollers in AFU, Ted Frank and snopes, are also two of the most consistent posters of serious research.

- ↑ "About Us". FactCheck.org. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Jackson, Brooks (December 4, 2003). "Gephardt TV Ad Misleads on Job Loss. A Gephardt ad in Iowa says 'George Bush has lost more jobs since any President since Herbert Hoover.' That's not exactly true.". FactCheck.org. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Bill Adair, PolitiFact Editor, Named Knight Professor at Duke". Duke University. April 5, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Guide to Washington Post Fact Checker Rating Scale". Voices.washingtonpost.com. December 29, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ↑ "About Full Fact". Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Annual reports". Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Correctiv on Twitter". Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Poynter Names Fact-Checking Expert Alexios Mantzarlis Director and Editor of the New International Fact-Checking Network, Based at its Florida Headquarters". Poynter Institute. September 21, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ↑ "About the International Fact-Checking Network". Poynter Institute. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ↑ Kessler, Glenn (September 15, 2016). "Fact-checking organizations around the globe embrace code of principles". Washington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ↑ Burgess, Matt. "Google is helping Full Fact create an automated, real-time fact-checker. The UK fact-checkers are hoping to publish two automatic tools by the end of 2017".

- ↑ Mosseri, Adam (December 15, 2016). "News Feed FYI: Addressing Hoaxes and Fake News". Facebook. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Tsukayama, Hayley (December 15, 2016). "Facebook will start telling you when a story may be fake". Washington Post. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Chappell, Bill (December 15, 2016). "Facebook Details Its New Plan To Combat Fake News Stories". NPR. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Isaac, Mike (December 15, 2016). "Facebook Mounts Effort to Limit Tide of Fake News". New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Hale, Virginia (January 3, 2017). "Revealed: 1,000-Man Mob Attack Police, Set Germany's Oldest Church Alight on New Year's Eve". Breitbart News. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Faiola, Anthony; Kirchner, Stephanie (January 6, 2017). "'Allahu akbar'-chanting mob sets alight Germany's oldest church? Shocking story, if it were true.". Washington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Holt, Jared (January 9, 2017). "Germany Investigating "Unprecedented Proliferation" Of Fake News In Wake Of Fabricated Breitbart Story". Media Matters for America. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Toor, Amar (January 10, 2017). "Germany investigates fake news after bogus Breitbart story. Officials suspect Russian meddling ahead of parliamentary elections". The Verge. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Germany investigating unprecedented spread of fake news online. Government focus on false reporting comes amid claims that Russia is trying to influence German election later this year". Reuters. January 9, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Kassam, Raheem (January 8, 2017). "Fake 'Fake News': Media Sow Division with Dishonest Attack on Breitbart's 'Allahu Akbar' Church Fire Story". Breitbart News. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Gertz, Matt (January 9, 2017). "Breitbart Has A Literally Unbelievable Response To Its False German Church Story". Media Matters for America. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ↑ "UK launches inquiry into the 'phenomenon of fake news'. MPs will investigate where fake news comes from, how it spreads and what its impact is". Wired. January 30, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ "'Fake news' inquiry launched". United Kingdom Parliament. January 30, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ "'Fake news' inquiry". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved May 22, 2017.