Timeline of cellular agriculture

This page is a timeline of major events in the history of cellular agriculture. Cellular agriculture refers to the development of agricultural products – especially animal products – from cell cultures rather than the bodies of living organisms. This includes in vitro or cultured meat, as well as in vitro dairy, eggs, leather, gelatin, and silk. In recent years a number of cellular animal agriculture companies and non-profits have emerged due to technological advances and increasing concern over the animal welfare and rights, environmental, and public health problems associated with conventional animal agriculture.[1]

Contents

Full timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1912 | French biologist Alexis Carrel keeps a piece of chick heart muscle alive in a Petri dish, demonstrating the possibility of keeping muscle tissue alive outside of the body.[2] |

| 1930 | Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead predicts that "“It will no longer be necessary to go to the extravagant length of rearing a bullock in order to eat its steak. From one 'parent' steak of choice tenderness it will be possible to grow as large and as juicy a steak as can be desired."[3] |

| 1932 | Winston Churchill writes "Fifty years hence we shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium."[3] |

| Early 1950s | Willem van Eelen recognizes the possibility of generating meat from tissue culture.[2] |

| 1971 | Russell Ross achieves the in vitro cultivation of muscular fibers.[4] |

| 1995 | The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves the use of commercial in-vitro meat production.[5] |

| 1999 | Willem van Eelen secures the first patent for in vitro meat.[2] |

| 2001 | NASA begins in vitro meat experiments, producing cultured turkey meat.[6][7] |

| 2002 | Researchers culture muscle tissue of the common goldfish in Petri dishes. The meat was judged by a test-panel to be acceptable as food.[2] |

| 2003 | Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr of the Tissue Culture and Art Project and Harvard Medical School produce an edible steak from frog stem cells.[8] |

| 2004 | Jason Matheny founds New Harvest, the first non-profit to work for the development of cultured meat.[3] |

| 2005 | Dutch government agency SenterNovem begins funding cultured meat research.[9] |

| 2005 | The first peer-reviewed journal article on lab-grown meat appears in Tissue Engineering.[10] |

| 2008 | The In Vitro Meat Consortium holds the first international conference on the production of in vitro meat.[11] |

| 2008 | People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals offers a $1 million prize to the first group to make a commercially viable lab-grown chicken by 2012.[5] |

| 2011 | The company Modern Meadow, aimed at producing cultured leather and meat, is founded.[12] |

| 2013 | The first in vitro hamburger, developed by Dutch researcher Mark Post's lab, is taste-tested.[13] |

| 2014 | Muufri and Clara Foods, companies aimed at producing cultured dairy and eggs, respectively, are founded with the assistance of New Harvest.[14][15] |

| 2014 | Real Vegan Cheese, a startup aimed at creating cultured cheese, is founded.[16] |

| 2014 | Modern Meadow presents "steak chips", discs of lab-grown meat that could be produced at relatively low cost.[12] |

| 2015 | The Modern Agriculture Foundation, which focuses on developing cultured chicken meat (as chickens make up the large majority of land animals killed for food[17]), is founded in Israel.[18] |

| 2015 | According to Mark Post's lab, the cost of producing an in vitro hamburger patty drops from $325,000 in 2013 to less than $12.[19] |

| 2016 | New Crop Capital, a private venture capital fund investing in alternatives to animal agriculture - including cellular agriculture - is founded. Its $25 million portfolio includes in vitro meat company Memphis Meats and in vitro collagen company Gelzen, along with Lighter, a software platform designed to facilitate plant-based eating, a plant-based meal delivery service called Purple Carrot, a dairy alternative Lyrical Foods, the New Zealand plant-based meat company SunFed Foods, and alternative cheese company Miyoko’s Kitchen.[20] |

| 2016 | The Good Food Institute, an organization devoted to promoting alternatives to animal food products - including cellular agriculture - is founded.[21] |

| 2016 | Memphis Meats announces the creation of the first in vitro meatball.[22] |

| 2016 | New Harvest hosted New Harvest 2016: Experience Cellular Agriculture, the first-ever global cellular agriculture conference.[23] |

| 2020-01-22 | Memphis Meats received a US$161 million investment in its Series B, which is more than everything that had been invested in the industry so far which was US$155 million.[24] |

Numerical and visual data

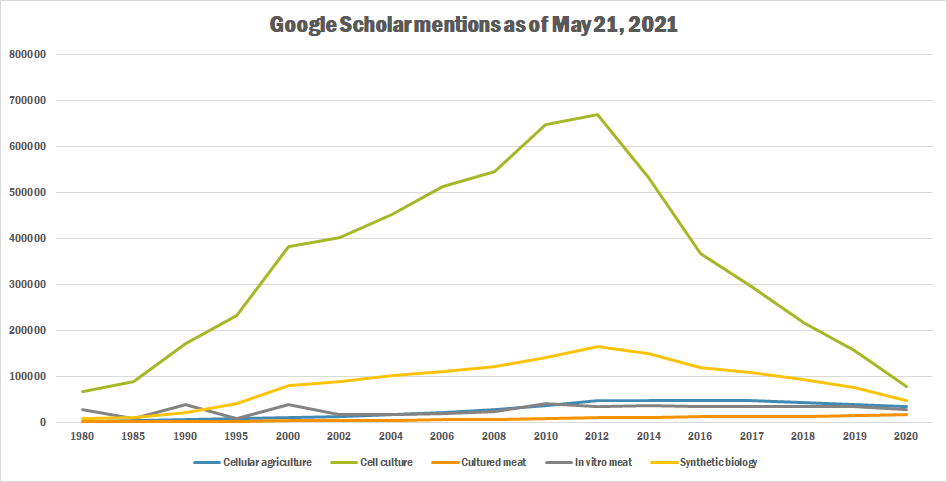

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 21, 2021.

| Year | Cellular agriculture | Cell culture | Cultured meat | In vitro meat | Synthetic biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1,910 | 65,700 | 1,010 | 27,900 | 7,360 |

| 1985 | 2,580 | 87,600 | 850 | 6,870 | 10,400 |

| 1990 | 5,140 | 170,000 | 2,030 | 37,800 | 21,000 |

| 1995 | 6,970 | 231,000 | 1,810 | 8,640 | 40,500 |

| 2000 | 10,800 | 381,000 | 4,070 | 38,000 | 79,900 |

| 2002 | 12,300 | 402,000 | 3,530 | 15,800 | 88,800 |

| 2004 | 15,700 | 452,000 | 4,370 | 15,900 | 102,000 |

| 2006 | 22,000 | 512,000 | 5,560 | 18,200 | 111,000 |

| 2008 | 28,500 | 544,000 | 6,100 | 23,800 | 121,000 |

| 2010 | 35,300 | 648,000 | 8,500 | 40,400 | 141,000 |

| 2012 | 46,200 | 670,000 | 10,600 | 34,900 | 164,000 |

| 2014 | 47,400 | 533,000 | 11,000 | 37,000 | 150,000 |

| 2016 | 47,800 | 366,000 | 11,800 | 33,800 | 119,000 |

| 2017 | 46,700 | 295,000 | 12,700 | 34,600 | 107,000 |

| 2018 | 43,600 | 216,000 | 13,100 | 34,100 | 93,000 |

| 2019 | 39,400 | 155,000 | 13,700 | 34,200 | 74,600 |

| 2020 | 34,000 | 78,200 | 16,200 | 28,000 | 46,000 |

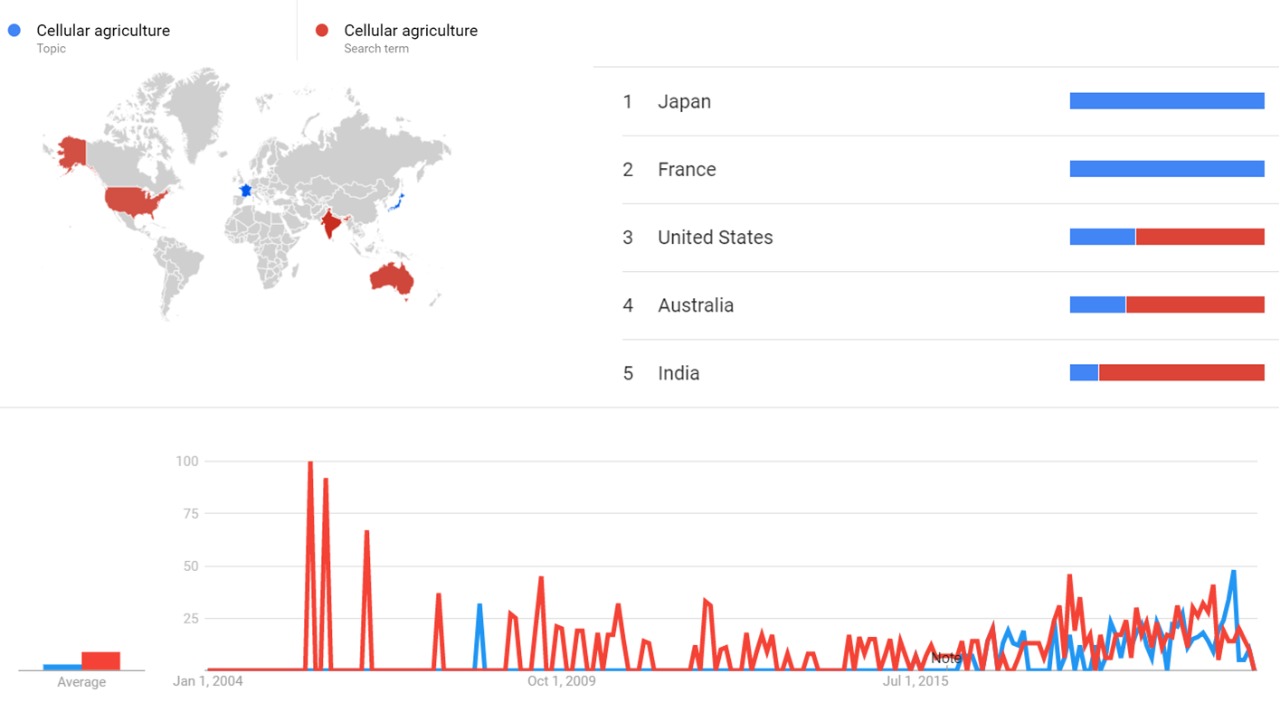

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for cellular agriculture (search term and topic) from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[25]

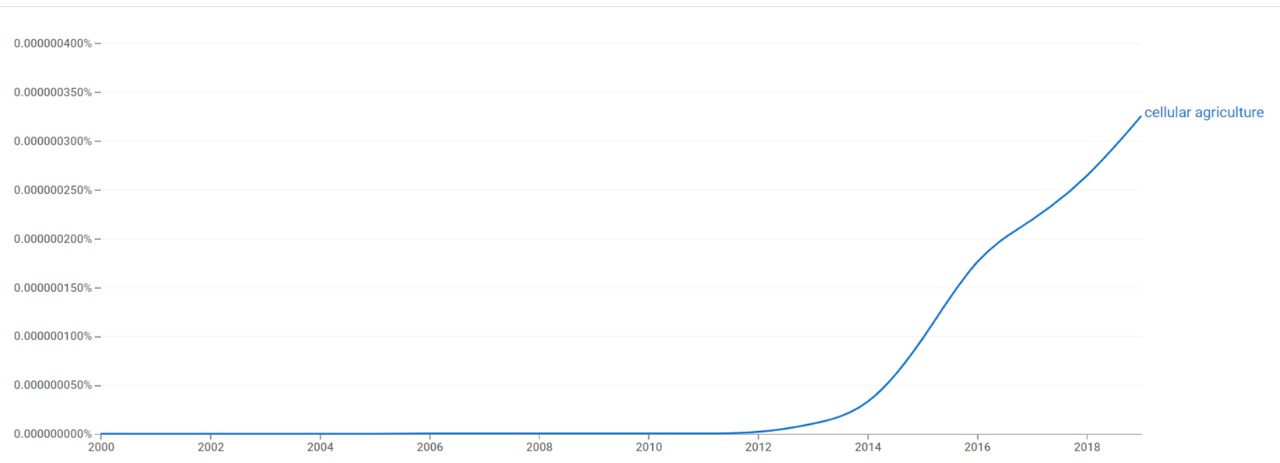

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for cellular agriculture, from 2000 to 2019.[26]

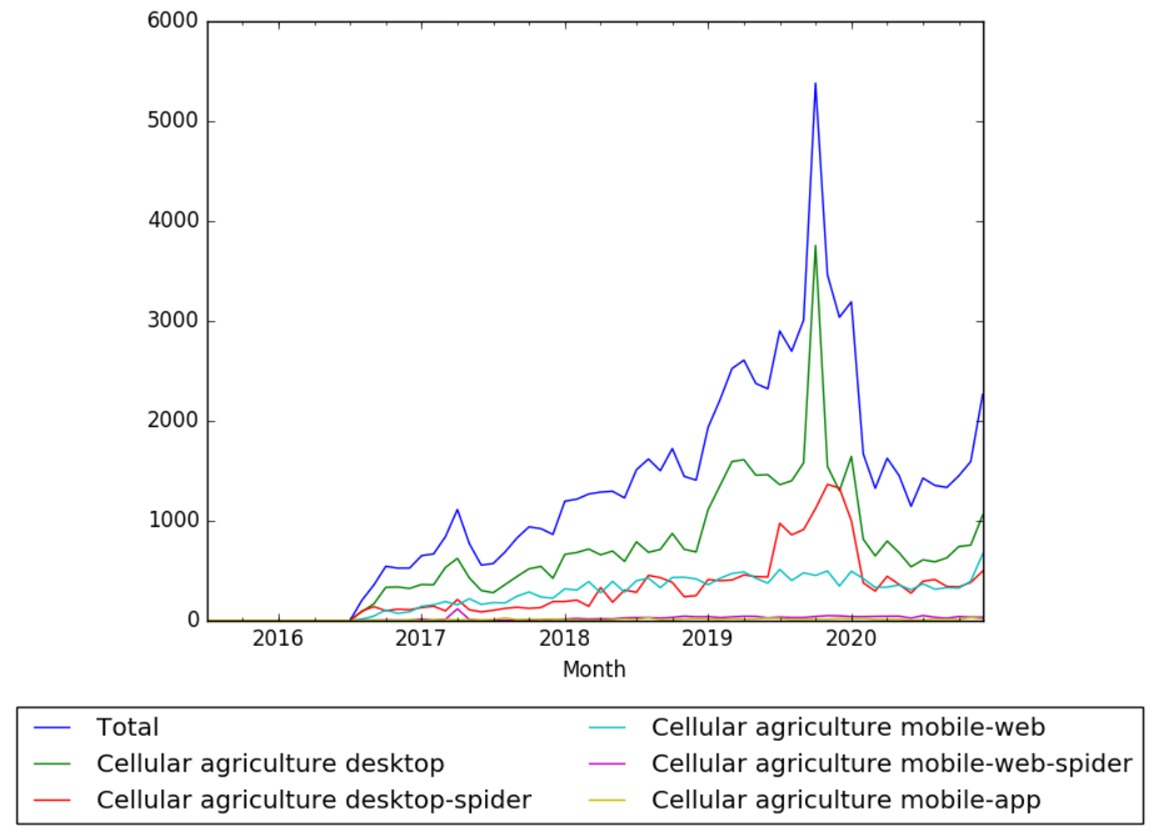

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Cellular agriculture, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to December 2020. The article was created in August 2016.[27]

See also

What the timeline is still missing

References

- ↑ "Cellular agriculture for a brighter future". March 22, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Zuhaib Fayaz Bhat; Hina Fayaz (April 2011). "Prospectus of cultured meat—advancing meat alternatives". Journal of Food Science Technology. 48 (2). PMC 3551074

.

.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Culturing Meat for the Future: Anti-Death Versus Anti-Life" (PDF). Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Ross, Russell (1 July 1971). "Growth of Smooth Muscle in Culture and Formation of Elastic Fibers". The Journal of Cell Biology. pp. 172–186. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Moments in Meat History Part IX – In-Vitro Meat". December 31, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Macintyre, Ben (2007-01-20). "Test-tube meat science's next leap". The Australian. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ↑ Webb, Sarah (2006-01-08). "Tissue Engineers Cook Up Plan for Lab-Grown Meat (The Year in Science: Technology)". Discover. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Ingestion / Disembodied Cuisine". Cabinet Magazine. Winter 2004–2005.

- ↑ Isha Datar (November 3, 2015). "Mark Post's Cultured Beef". Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Paper Says Edible Meat Can be Grown in a Lab on Industrial Scale" (Press release). University of Maryland. 2005-07-06. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ Siegelbaum, D.J. (2008-04-23). "In Search of a Test-Tube Hamburger". Time. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chelsea Harvey (September 26, 2014). "This Brooklyn Startup Wowed The Science Community With Lab-Made 'Meat Chips'". Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Henry Fountain (August 5, 2013). "A Lab-Grown Burger Gets a Taste Test". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ Isha Datar (November 5, 2015). "Muufri: Milk without Cows". Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Isha Datar (November 4, 2015). "Clara Foods: Egg Whites without Hens". Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ Marcus Wohlsen (April 15, 2015). "Cow Milk Without the Cow is Coming to Change Food Forever". Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ↑ United Poultry Concerns. "Chickens". Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ Abigail Klein Leichman (November 19, 2015). "Coming soon: chicken meat without slaughter". Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Cost of lab-grown burger patty drops from $325,000 to $11.36". April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ↑ Louisa Burwood-Taylor (March 17, 2016). "New Crop Capital Closes $25m Fund, Invests in Beyond Meat". Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ Nil Zacharias (March 16, 2016). "The Race to Disrupt Animal Agriculture Just Got a $25 Million Shot in the Arm, and a New Non-Profit". Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ Hilary Hanson (February 2, 2016). "'World's First' Lab-Grown Meatball Looks Pretty Damn Tasty". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ "First-ever cellular agriculture conference". May 31, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Memphis Meats' investment more than doubles global investment". The Good Food Institute. 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ↑ "Cellular agriculture". trends.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cellular agriculture". books.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cellular agriculture". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 19 January 2021.