Timeline of the Humane Society of the United States

This is a timeline of the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), one of the largest animal protection organizations in the world. HSUS supports animal protection through investigation, legislation, legal action, education, consumer advocacy, and multimedia campaigns.[1]

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1970s | In the late decade, utilization of a variety of media becomes a more important part of promoting animal welfare issues.[1] |

| 1980s | As a background, the decade sees the rise of the animal rights movement along with groups that advocate extralegal activities in furtherance of their cause. Some of these activities are violent in nature, consisting of activities like theft and property destruction.[2] In the 1980s, HSUS sponsors several validation studies designed to demonstrate the value of humane education.[3][4] |

| 1990s< | HSUS experiences a period of tremendous growth in member acquisition and fundraising, upon the promotion of Paul Irwin to president. Irwin sets an ambitious goal of having five million constituents within five years. This goal is achieved ahead of schedule. Between 1994 and 1997, the membership rolls of HSUS grow from 2.2 to 5.7 million supporters. HSUS' annual budget grows from $3.5 million to $70 million between 1983 and 2003 and the number of full-time staff increases from around 60 to 280 employees.[2] |

| Present time | Today, HSUS is based in Washington, D.C., with nine regional offices, eight affiliates and an international arm. Its has over 500 paid staff members, including veterinarians, biologists, lawyers and behaviorists, as well as the volunteers that work throughout the United States. It boasts about 10 million members and constituents and saw a total revenue of more than $100 million in 2006, with more than $91 million coming directly from public support.[5] |

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1866 | Prelude | The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is founded. It is the first organization of its kind in the United States.[5] | |

| 1877 | Prelude | The American Humane Association (AHA)is founded.[2] | |

| 1883 | Prelude | The American Anti-Vivisection Society is founded.[2] | |

| 1954 | Founding | The Humane Society of the United States is founded, when a split develops within the American Humane Association (AHA) over whether to fight legislation requiring shelters to turn over animals for use in research. The founders resolve to form a strong humane organization that would recognize and work to eliminate all forms of cruelty and injustice to animals. Robert J. Chenoweth is chosen to lead the organization, with Oliver M. Evans as director.[1][6] | |

| 1955 | April | Publication | HSUS establishes a bimonthly newsletter, HSUS News, in order to inform constituents of the organization's activities.[1] |

| 1957 | Expansion | To extend the scope of its work, HSUS begins to organize self-supporting state branches.[1] | |

| 1958 | Law | The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act is passed. It is considered the first success of HSUS. The act protects food animals during slaughter.[1][6] | |

| 1960 | Partnership | Local humane societies begin to be allowed to affiliate with HSUS when meeting certain standards of operation.[1] | |

| 1961 | Publication | HSUS publishes landmark book Animals in a Research Laboratory, with the intent to enlighten the public on the moral and political issues involved in animal welfare.[1] | |

| 1961 | Campaign | HSUS' investigator Frank McMahon launches a probe of dog dealers around the country to generate support for a federal law to prevent cruelty to animals destined for use in laboratories. The five-year investigation into the multilayered trade in dogs would pay off in February 1966 when Life publishes a photo-essay of a raid conducted on a Maryland dog dealer's premises by McMahon and the state police.[7][8] | |

| 1966 | Law | HSUS, the American Humane Association, and other interested parties secure the passage of the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act, which addresses the issue of pet theft by regulating animal suppliers and requiring research laboratories to purchase animals from licensed dealers. With this step, HSUS opens a door for accountability in the research laboratories.[1][6] | |

| 1967 | Law | Promoted by HSUS, the Endangered Species Act is passed.[1] | |

| 1970 | April 1 | Staff | John Hoyt is hired president of HSUS.[2] |

| 1970 | December | Law | Promoted by HSUS, the Horse Protection Act is signed into law.[9][1] |

| 1971 | December | Law | Promoted by HSUS, the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act is signed into law.[1] |

| 1972 | December | Law | Promoted by HSUS, the Marine Mammal Protection Act is passed.[1] |

| 1973 | Organization | The National Association for Humane and Environmental Education is formed by HSUS.[1] | |

| 1973 | Organization | The National Association for the Advancement of Humane Education (NAAHE) is established by HSUS, with the purpose of bringing compassion for animals to schools, NAAHE would start a magazine for teachers, entitled Humane Education; develop multimedia curriculum materials; and hold teacher training seminars and professional development programs.[1] | |

| 1975 | Facility | HSUS purchases its own office space, a five-story building in Washington, D.C.[1] | |

| 1976 | Program | HSUS establishes disaster relief plans to protect pets and their caregivers during an emergency.[1] | |

| 1977 | Publication | HSUS publishes On the Fifth Day, a collection of essays by scholars supporting a humane philosophy regarding animals.[1] | |

| 1978 | Attorneys Robert Welborn and Murdaugh Stuart Madden[10] conduct a workshop at HSUS annual conference, "Can Animal Rights Be Legally Defined?", and assemble constituents passed a resolution to the effect that "animals have the right to live and grow under conditions that are comfortable and reasonably natural... animals that are used by man in any way have the right to be free from abuse, pain, and torment caused or permitted by man... animals that are domesticated or whose natural environment is altered by man have the right to receive from man adequate food, shelter, and care."[11] | ||

| 1979 | Growth | HSUS' membership includes now 115,000 people, the staff counting 80 employees, and the budget approaches $2 million.[1][2] | |

| 1981 | Campaign | HSUS launches a consumer advocacy campaign, No Veal This Meal, opposing the practices used to raise milk-fed veal calves. The program succeeds as many consumers refuse to buy milk-fed veal, considered a delicacy.[1] | |

| 1984 | A General Accounting Office reports confirmed HSUS allegations of major problems with puppy mills in the United States, setting the stage for proposed legislation to regulate mills in the 1990s.[12] | ||

| 1986 | Organization | The Center for Respect of Life and Environment (CRLE) is created by HSUS, with aims at promoting humane values and collaboration in the fields of higher education, religion, the professions, and the arts. The efforts of CRLE prove important for students facing dissection requirements.[1] | |

| 1986 | HSUS employee John McArdle declares that "HSUS is definitely shifting in the direction of animal rights faster than anyone would realize from our literature".[13] | ||

| 1988 | HSUS pioneers the use of a fertility-control vaccine for nonlethal animal population control, after animal overpopulation, long a concern of HSUS, becomes of focus of new programs.[1] | ||

| 1988 | Campaign | HSUS launches its Be a P.A.L. (Prevent a Litter) campaign. One shelter establishes the policy of sterilization at adoption, whereby pets are sterilized before they leave the shelter with their new caregivers.[1] | |

| 1988 | Campaign | HSUS launches the Shame of Fur campaign, informing Americans of the poor living conditions of animals used to make clothing.[1] | |

| 1990 | Campaign | HSUS calls for a national boycott of dogs raised in puppy-mills, after investigating for more than ten years over 600 puppy breeding facilities in the Midwest, particularly Nebraska, Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. In addition to finding poor living conditions, HSUS finds that repeated breeding produces unhealthy dogs with temperament disorders.[1] | |

| 1990 | Program | HSUS launches The Beautiful Choice program, in order to promote boycotting of cosmetics and personal care product manufacturers that test on animals.[1] | |

| 1990 | HSUS starts expressing a clear opposition to "the use of threats and acts of violence against people and willful destruction and theft of property."[14][15][16] | ||

| 1991 | Organization | The Humane Society International is established.[1] | |

| 1991 | Event | HSUS hosts its first Animal Care Expo, which grows to be the world's largest trade show for animal care professionals. Attended by professionals from around the globe, the annual event features speakers, workshops, and day-long courses to provide information on advances in sheltering.[1] | |

| 1991 | Advocating alternatives to animal use in research and testing, HSUS establishes the Russell and Burch Award. The award is given for outstanding scientific achievement that fit with HSUS's "three R's": to Reduce the number of animals used in experiments; to Replace animals with other methods of obtaining results; and Refine experimental design to reduce the need for animal use.[1] | ||

| 1992 | Organization | The Humane Society International (HSI) is established by HSUS. HSI's first work involves addressing the problem of animals and birds confiscated in the illegal wildlife trade.[1] | |

| 1992 | Staff | Treasurer and Chief financial officer Paul Irwin is promoted to president of HSUS.[2] | |

| 1995 | Program | HSUS initiates a program to loan humane alternatives to animal dissection students. The program would double in size within three years.[1] | |

| 1995 | Campaign | The first annual National Dog Bite Prevention Week is founded by HSUS.[1] | |

| 1995 | The Wildlife Land Trust is established bu HSUS, in order to protect wildlife and habitats around the globe.[1][5] | ||

| 1996 | Campaign | The National Animal Shelter Appreciation Week is founded by HSUS.[1] | |

| 1997 | Program | HSUS conceives the program First Strike to promote understanding of the link between animal abuse and abuse to persons. In collaboration with law enforcement, prosecutors, courts, and domestic violence prevention groups, the program is aimed at facilitating communication between animal protection groups and witnesses to family and social violence.[1] | |

| 1997 | Program | HSUS launches the Soul of Agriculture program.[1] | |

| 1997 | Staff | HSUS' president Paul Irwin is named Chief executive officer after John Hoyt’s retirement.[2] | |

| 1998 | HSUS opposes the Makah Whale Hunt and urges President Clinton to impose trade sanctions on Japan due to its whaling policies.[1] | ||

| 2000 | Publication | The Humane Society Press is launched by HSUS. It publishes professional and scholarly books on animal-welfare topics.[6][1] | |

| 2000 | Campaign | HSUS launches the Fur Free 2000 campaign and Pain and Distress campaign, the latter for animal laboratory animals.[1] | |

| 2000 | HSUS' Pets for Life project expands with the formation of the Pets for Life National Training Center.[1] | ||

| 2000 | HSUS calls on the United States Navy to suspend sonar tests harmful to marine animals after nine whales are found dead in the Bahamas.[1] | ||

| 2000 | HSUS promotes legislation to protect companion animals and is involved in the formation of the Safe Air Travel for Animals Act.[1] | ||

| 2000 | Funding | HSUS founds the Humane Equity Fund with Salomon Brothers Asset Management. The fund aims at evaluating companies based on the threat they pose to the well-being of animals, such as through animal testing, and the use of animals for end-products. Pharmaceutical companies and many cosmetic companies are excluded automatically.[1] | |

| 2000 | Publication | HSUS publishes The Use of Animals in Higher Education.[1] | |

| 2001 | Campaign | As of date, HSUS' major campaigns target five issues: factory farming, animal blood sports, the fur trade, puppy mills, and wildlife abuse.[17] | |

| 2001 | January | HSUS calls for a Fur Free presidential inauguration ceremony. The idea is promoted through television advertising and 75 taillight advertisements on Washington, D.C. Metrobuses, stating, "You Should be Ashamed to Wear Fur."[1] | |

| 2001 | Publication | HSUS publishes The State of Animals, which describes the progress made for the benefit of animals over the past 50 years.[1] | |

| 2001 | October | Law | HSUS wins a victory with the passage of the Humane Slaughter Act Amendment.[1] |

| 2004 | Staff | Wayne Pacelle is named President and Chief executive officer of HSUS.[2] A former executive director of The Fund for Animals and named in 1997 as "one of America's most important animal rights activists",[18] the Yale graduate had spent a decade as HSUS's chief lobbyist and spokesperson, and expressed a strong commitment to expand the organization's base of support as well as its influence on public policies that affect animals.[19] Under Pacelle's leadership, HSUS would undertake several dozen ballot initiative and referendum campaigns in a number of states, concerning issues like unsportsmanlike hunting practices, cruelty in industrial agriculture, greyhound racing, puppy mill cruelty and animal trapping.[20][21][22] | |

| 2005 | Organization | The Fund For Animals and the Doris Day Animal League merge into HSUS, greatly expanding the size and capabilities of the organization.[2] | |

| 2005 | Program | The HSUS's campaign to end the hunting of seals is launched in Canada, securing pledges from 300 restaurants and companies, plus 120,000 individuals, to boycott Canadian seafood.[23] | |

| 2005 | Program | HSUS hatchs a plan to replace conventionally produced eggs served on college campuses with cage-free alternatives, by appealing to students’ interest in social issues and addressing administrators’ practical concerns.[24] | |

| 2005–2006 | Campaign | When thousands of animals are left behind as people evacuate during Hurricane Katrina, HSUS join other organizations in a massive search-and-rescue effort that end up saving approximately ten thousand animals, and raises more than $34 million for direct relief, reconstruction, and recovery in the Gulf Coast region. HSUS leads the campaign that culminate in the federal passage of the PETS Act in October 2006, requiring all local, state, and federal agencies to include animals in their disaster planning scenarios.[25] | |

| 2006 | October | Law | Promoted by HSUS, the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards (PETS) Act is signed into law. The Act requires that animals be taken into account in the disaster plans of local, state, and federal agencies.[6] |

| 2007 | Program | HSUS launches a program designed to advance relationships and awareness within the American faith community at all levels. The program provides speakers, produces videos and other materials, and works with faith leaders to lead discussion of animal issues within the broader religious community.[26][27][28] HSUS works on this program with Farm Forward, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that implements innovative strategies to promote conscientious food choices, reduce farmed animal suffering, and advance sustainable agriculture.[29] | |

| 2008 | Early | Organization | HSUS re-organizes its direct veterinary care work and its veterinary advocacy under a new entity, the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association, formed through an alliance with the Association of Veterinarians for Animal Rights (AVAR).[30] |

| 2008 | The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) recalls more than 140 million pounds of beef (the largest meat recall in U.S. history to date) following an HSUS investigation at the Hallmark/Westland Meat Packing Company in California, which exposes significant animal abuse.[6] | ||

| 2008 | HSUS offers a reward for information leading to the identification and arrest of parties involved with the firebombing of two University of California animal researchers.[31] | ||

| 2013 | Recognition | The Chronicle of Philanthropy identifies HSUS as the 136th largest charity in the United States in its Philanthropy 400 listing.[32][33] | |

| 2014 | August | Recognition | Wayne Pacelle is again named to the NonProfit Times' "Power and Influence Top 50" for his achievements in leading HSUS, the fourth time he has been so recognized.[34] |

| 2014 | Campaign | The campaign hunting of seals claim more than 6,500 restaurants, grocery stores and seafood supply companies were participants the Protect Seals campaign.[35] | |

| 2014 – 2018 | Recognition | Animal charity evaluator Animal Charity Evaluators recommends HSUS' Farm Animal Protection Campaign as a Standout Charity between May 2014 and February 2018.[36] | |

| 2016 | November | Recognition | In their review of HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign, Animal Charity Evaluators cite their strengths as their large reach, strategic approach, and long track record of legal work, corporate outreach, and meat reduction programs. ACE states that their primary concern with the Farm Animal Protection Campaign is that it is unclear the extent to which their budget comes from HSUS general budget, and whether small donations to the Farm Animal Protection Campaign would be fungible with other HSUS activities.[36] |

| 2018 | Controversy | The Washington Post reports on an investigation by the Humane Society board into allegations of sexual harassment involving Wayne Pacelle. The investigation finds three credible accusations of sexual harassment and female leaders who said their "warnings about his conduct went unheeded." [37] The board votes to keep Pacelle, but after several board members resign in protest and high-profile donors reveal they would withhold donations, Pacelle finally announces his resignation on February 2, 2018.[38] | |

| 2018 | February | Animal Charity Evaluators rescind their recommendation of HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign following allegations of misconduct from both the former president of HSUS and the former vice president of the Farm Animal Protection Campaign. This rescission is made because ACE believes strong, ethical leadership and a healthy work environment are critical components of an effective charity.[39] |

Numerical and visual data

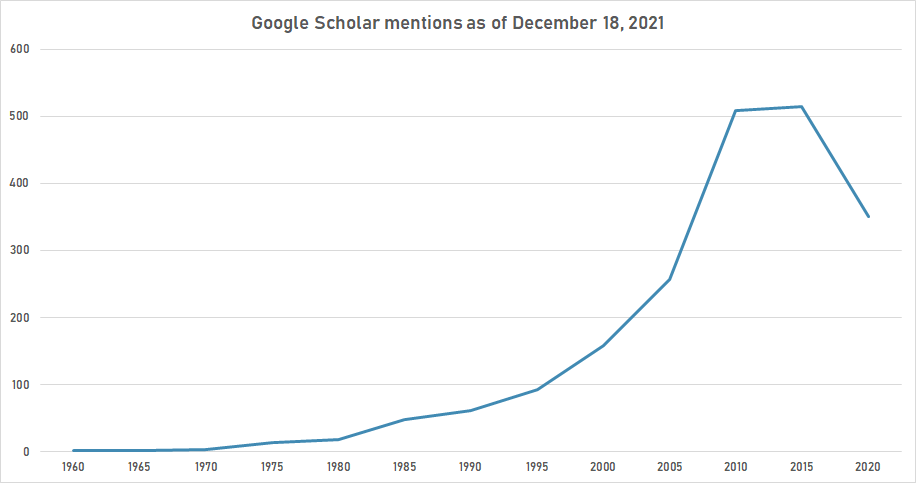

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 18, 2021.

| Year | "Humane Society of the United States" |

|---|---|

| 1960 | 1 |

| 1965 | 1 |

| 1970 | 3 |

| 1975 | 13 |

| 1980 | 18 |

| 1985 | 47 |

| 1990 | 61 |

| 1995 | 93 |

| 2000 | 158 |

| 2005 | 256 |

| 2010 | 509 |

| 2015 | 514 |

| 2020 | 350 |

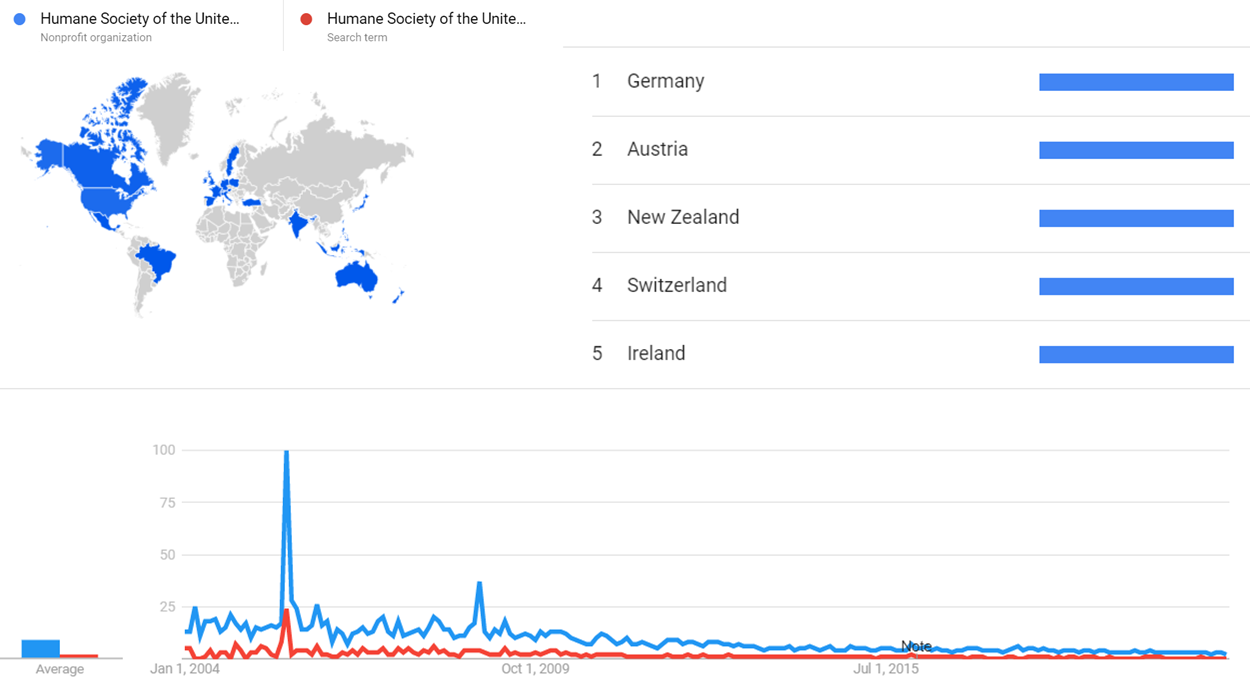

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Humane Society of the United States (Nonprofit organization) and Humane Society of the United States (Search term) from January 2005 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[40]

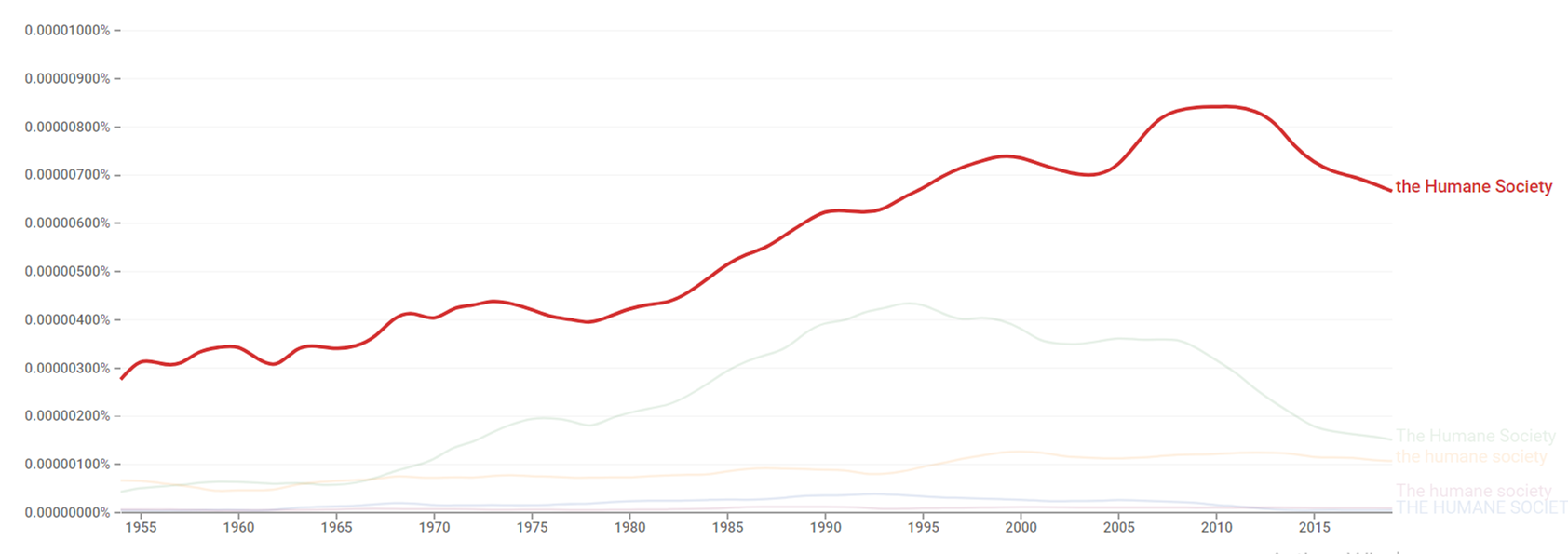

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for The Humane Society from 1954 to 2019.[41]

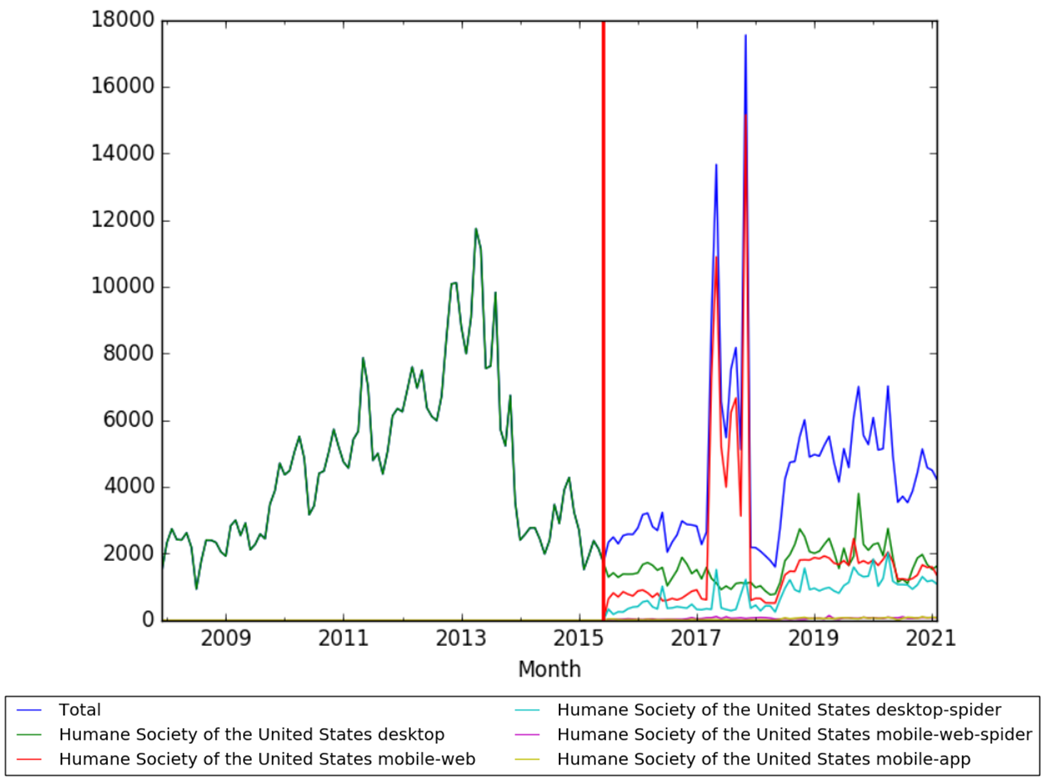

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Humane Society of the United States, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to February 2021.[42]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 "The Humane Society of the United States History". fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 "History of HSUS". waynepacelle.org. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Mom, Apple Pie ... and Humane Education", Humane Education (March 1983), pp. 7–9

- ↑ Ascione, F.; Children and Animals: Exploring the Roots of Kindness and Cruelty (2005), Purdue University Press; p. ix.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "All About the Humane Society Fund". animals.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Humane Society of the United States". britannica.com. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Unti, Bernard. "Frank McMahon: The Investigator Who Took a Bite Out of Animal Lab Suppliers". Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

The conditions that shocked the troopers were all too familiar to the man who led them on to Brown's property, Frank McMahon (1926–1975), HSUS director of field services.

- ↑ Wayman, Stan (February 4, 1966). "Concentration Camps for Dogs". Life. Vol. 60 no. 5. pp. 22–29. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

The raid was at the behest of the Humane Society of the United States, which, in its constant surveillance of places like Brown's around the country, had sent one of its agents to check conditions at Brown's twice within the past year

- ↑ "Horse Protection Act; Requiring Horse Industry Organizations To Assess and Enforce Minimum Penalties for Violations". federalregister.gov. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ "Murdaugh Stuart Madden: A Half Century's Service, A Lasting Legacy". HumaneSociety.org. Humane Society of the United States. January 14, 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ The Humane Society News (Winter 1979), pp. 16–19

- ↑ Unti, Protecting All Animals, 101–102.

- ↑ John McArdle, quoted in Katie McCabe, "Who Will Live, Who Will Die", Washingtonian, August 1986, p. 115, as cited in The Humane Society in the US: It's Not About Animal Shelters, Daniel Oliver

- ↑ "Joint Resolutions for the 1990s", HSUS News Spring 1991, 1.

- ↑ M. Stephens, "Clarifying Our Position", HSUS News Spring 1991, 21–23.

- ↑ "Dr. Steve Best, PhD". DrSteveBest.org. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Campaigns". HumaneSociety.org. Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Board of Directors". HumaneUSA.org. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Oldenburg, Don (August 9, 2004). "Vegan in The Henhouse". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Initiative and Referendum History – Animal Protection Issues. Humane Society of the United States.

- ↑ Humane Society of the United States – Ballotpedia.org

- ↑ Rouen, Ethan. "Wayne Pacelle | Humane Society Of The United States | Leading Lobbyist For Animal Welfare". American Way Magazine. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Canadian Seafood Boycott Ends Year With Growing Momentum". UnderwaterTimes.com. December 20, 2005. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Cage-Free Campus". toolsofchange.com. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ President Bush Signs Bill to Leave No Pet Behind in Disaster Planning and Evacuation; Humane Society of the United States; October 6, 2006. Template:Webarchive

- ↑ Dallas, Kelsey (October 25, 2014). "Humane Society emphasizes faith connection in new video series". deseretnews.com. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Christine Gutleben". Q. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Mark (13 July 2018). "Pet Ministries Are Growing in Churches". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Faith in Food: New Ethical Food Initiatives". farmforward.com. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Humane Society, Veterinarians for Animal Rights Join Forces". The Horse. 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Paddock, Richard C.; La Ganga, Maria L. (August 5, 2008). "Officials decry attacks on UC staff". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "The Chronicle of Philanthropy – The news and tools you need to change the world". philanthropy.com. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ October 16, 2011. Lists from the Philanthropy 400. The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

- ↑ "Data" (PDF). www.thenonprofittimes.com.

- ↑ "McMenamins joins Protect Seals Campaign". humanesociety.org. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign". AnimalCharityEvaluators.org. November 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Paquette, Danielle (January 29, 2018). "Humane Society CEO is subject of sexual harassment complaints from three women, according to internal investigation". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Paquette, Danielle (February 2, 2018). "Humane Society CEO resigns after sexual harassment allegations". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ Smith, Allison (February 2, 2018). "ACE'S Decision to Rescind Our Recommendation of HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign". Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "Humane Society of the United States". Google Trends. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ↑ "The Humane Society". books.google.com. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ↑ "Humane Society of the United States". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 14 March 2021.