Timeline of hepatitis

This is a Timeline of hepatitis, describing major events such as epidemics and medical developments, related to hepatitis A, B, C, D and E.

Big Picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 5th century BC | Hepatitis already plagues mankind.[1] |

| 17th-19th century | Jaundice epidemics break out in military and civilian populations during wars.[2] |

| 20th century | It is first recognized that viruses introduced by fecally contaminated food and water are responsible for hepatitis infection.[3] Multiple scientific developments from the second half of the century establish the current basis of knowledge and treatment of the H viruses. |

| 1960s–1970s | Several important milestones in the history of viral hepatitis happen in the 1960s.[4] The hepatitis c virus is identified. Blood tests to detect the hepatitis A and B infection are developed.[5] Modern viral hepatitis research begins with the discovery of Australia antigen.[4] |

| 1980s | Hepatitis B vaccine starts implementation worldwide.[6] |

| 1990s–2000s | The first Interferon alfa is approved for the treatment for hepatitis C.[7] Multiple drugs are developed for combating hepatitis. The World Hepatitis Alliance is founded.[7] |

| Recent years | There isn’t a vaccine for hepatitis C virus at this time.[8] About 375 million people are infected with the hepatitis B virus. HBV has killed more people than AIDS and is the cause of millions of cases of liver cancer.[9] Most cases of HB are found in the Asia-Pacific region.[6] In 2009, it was estimated that about 1.4 million cases of hepatitis A occurred worldwide.[10] Hepatitis E primarily occurs in South Asia and Africa.[3] |

Full timeline

| Year/period | Hepaitis type | Type of event | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 BC | Hepatitis B | Medical development | The earliest description of epidemic hepatitis, which may or may not have been due to hepatitis B virus, is credited to Greek physician Hippocrates, who describes a condition he called “epidemic jaundice”.[11][8] | Greece |

| 741–752 | Medical development | Pope Zachary quarantines individuals with jaundice to prevent its spread throughout Rome, suggesting an apparent infectious nature of this clinical finding.[4] | ||

| 1861–1865 | Epidemic | Large hepatitis epidemic is documented during the American Civil War. 52,000 cases are estimated.[12][11] | United States | |

| 1870 | Epidemic | Large hepatitis epidemic breaks out during the Franco–Prussian War.[11] | ||

| 1865 | Scientific development | German physician Rudolf Virchow describes a patient with symptoms of epidemic jaundice in whom the lower end of the common bile duct was blocked with a plug of mucus. This would lead to the term “catarrhal jaundice,” because the disease is believed to be caused by catarrh as a result of mucus obstructing the bile duct.[4] | ||

| 1885 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | A. Lurman first describes an epidemic of serum hepatitis among 191 German ship workers in Bremen after a smallpox vaccination campaign using human lymph. It is the earliest record of an epidemic caused by hepatitis B virus.[6][11][4] | Germany |

| 1908 | Scientific development | S. McDonald publishes the hypothesis that the infectious jaundice is caused by a virus.[2][4] | ||

| 1912 | Medical development | The name Hepatitis is first implemented.[3] | ||

| 1914–1918 | Epidemic | Hepatitis epidemic breaks out during World War I.[11] | ||

| 1942–1945 | Hepatitis C | Epidemic | Approximately 182,383 service members are hospitalized for Hepatitis C during World War II. The disease is contracted in two different ways. An epidemic of hepatitis breaks out among many service members who were vaccinated against yellow fever. The source of the infection is traced to the serum, or clear fluid in the blood, that is used in the vaccine. This form of the disease becomes known as serum hepatitis. A different form of hepatitis, acute hepatitis, is found among soldiers who have received blood transfusions.[8] | Europe |

| 1947 | Scientific development | MacCallum classifies viral hepatitis into two types. Viral hepatitis B is classified as serum hepatitis.[4] | ||

| 1951 | Scientific development | Researchers describe a form of chronic hepatitis occurring primarily in young women. Because nearly 15% of these patients have positive lupus erithematosus cell tests, this disorder is first called lupoid hepatitis. By the 1970s its autoimmune origine would be discovered, and today the condition is referred as autoimmune hepatitis.[3] | ||

| 1953 | Medical development | Hepatitis becomes a reportable disease.[3] | ||

| 1957 | Scientific development | Scientists find that interferon could act as an antiviral drug. The name interferon is given since it could “interfere” with replication or multiplication of the virus.[5] | ||

| 1963 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | Blood test to detect hepatitis B infection is developed.[5] | |

| 1963–1965 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | The hepatitis B virus surface antigen HBsAg (also known as Australia antigen) is first identified.[4][11] | |

| 1967 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | American geneticist Baruch Samuel Blumberg and colleagues, while researching genetic links to disease susceptibility, discover the hepatitis B virus. In 1976, Dr. Blumberg would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery.[8][13] | |

| 1967 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | Krugman and colleagues recognize the parenterally transmitted nature of hepatitis B, which would lead to the formulation of hygienic measures to prevent the disease.[11] | |

| 1968 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | Prince, Murakami, and Okochi, through independent studies, confirm that the Australia antigen is found specifically in patients who had serum hepatitis (hepatitis B).[4] | |

| 1969 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | American physician Baruch Samuel Blumberg and colleagues develop the blood test that is used to detect the hepatitis B virus, and develop the first hepatitis B vaccine.[13] | |

| 1970 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | DS Dane first describes the 42–47 nm double shelled particles (today called Dane particles) as the actual infectious particles, produced by the hepatitis B virus.[11][4] | |

| 1973 | Hepatitis A | Scientific development | American researchers Stephen Feinstone, Albert Kapikian and Robert Purcell, working at the National Institutes of Health, identify the virus responsible for hepatitis A. The virus is discovered in fecal samples from prisoner volunteers.[8] | United States |

| 1973 | Hepatitis A | Scientific development | Blood test to detect hepatitis A infection is developed.[5] | |

| 1974 | Hepatitis A | Medical development | The application of liposomes as a vaccine delivery vehicle is first reported. Since then, liposome-based vaccines against hepatitis A (Epaxal) and influenza (Inflexal V) would be approved for human use.[14] | |

| 1975 | Unrecognized | Scientific development | American and British researchers identify a type of hepatitis that doesn’t test positive for the proteins found with hepatitis A virus or hepatitis B virus. Both teams conclude that a previously unrecognized human hepatitis virus is the likely cause.[8] | |

| 1977 | Hepatitis D | Scientific development | Rizzetto and coworkers discover the Hepatitis D virus, while trying to find out why some petients with hepatitis B virus infection have more serious disease than others.[15] | |

| 1977 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | Dr Chung Young Kim in South Korea develops a hepatitis B vaccine, which becomes known as "Kim's vaccine", using serum from the blood of HBV-infected patients.[16] | |

| 1978 | Hepatitis E | Scientific development | Soviet scientist Mikhail Balayan, investigating an outbreak of non-A, non-B hepatitis in Tashkent, discovers the hepatitis E virus, by transmitting the disease into himself by oral administration of pooled stool extracts of 9 patients with non-A and non-B hepatitis.[17][18] | Uzbekistan |

| 1981 | Hepatitis A | Medical development | American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman develops the first effective vaccine for Hepatitis A virus.[8] | United States |

| 1981 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | The first hepatitis B vaccine is approved in the United States.[19] This “inactivated” type of vaccine involves the collection of blood from hepatitis B virus-infected (HBsAg-positive) donors.[20] The vaccine is 95% effective in preventing infection and the development of chronic disease and liver cancer due to hepatitis B.[21] | United States |

| 1986 (May) | Hepatitis B | Medical development | Hepatitis B vaccine Recombivax HB (Merck) is first approved for marketing in West Germany, and two months later by the United States FDA.[22][23] This is the first genetically engineered vaccine[24], a recombinant vaccine resulting from two key discoveries, the expression of proteins in plasmids and the ability to sequence DNA. It is administered by intramuscular injection.[25][26][27] Posology consists in 3 doses (0.5 mL each) at 0, 1, and 6 months for infants, children, and adolescents 0–19 years of age (Pediatric/adolescent formulation), 2 doses (1.0 mL each) at 0 and 4–6 months for adolescentsb 11 through 15 years of age (adult formulation); 3 doses (1.0 mL each) at 0, 1, and 6 months for adults ≥20 years of age (Adult formulation); and 3 doses (1.0 mL each) at 0, 1, and 6 months for predialysis and dialysis patients (dialysis formulation).[28] | Germany, United States |

| 1986 | Hepatitis A | Scientific development | Provost et al. successfully prepare a killed hepatitis A vaccine, using virus grown in cell culture that is safe and protective in marmosets. Lewis et al. subsequently report development and early clinical testing of vaccine made from killed attenuated CR326 virus grown and purified from cell cultures of MRC-5 strain human diploid fibroblasts. The vaccine is more than 95% pure and is inactivated by formaldehyde and formulated in alum adjuvant.[29] | |

| 1987 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | The hepatitis B Vax II (recombinant) vaccine is introduced.[30] | |

| 1989 | Hepatitis C | Scientific development | The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Chiron Corporation working together identify the hepatitis C virus.[8] It is the first virus identified by a direct molecular approach.[12][7] | United States |

| 1989 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | Hepatitis B vaccine, Engerix-B, is approved.[31] It is administered by intramuscular injection.[32] | |

| 1990–1992 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | Screening the blood supply for hepatitis C virus begins in the United States. In 1992, a more sensitive test becomes available, thus eliminating the risk from known genotypes of HCV.[8] | United States |

| 1991 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves Interferon alfa-2b (Intron A), for the treatment of hepatitis C virus.[8] | United States |

| 1991 | Hepatitis A | Medical development | Havrix (by GlaxoSmithKline) is approved in Switzerland and Belgium. It is the world's first hepatitis A vacine.[33][34] | Switzerland, Belgium |

| 1991 | Hepatitis B | Policy | Egypt introduces childhood immunization against hepatitis B virus.[6] | Egypt |

| 1991 | Hepatitis B | Recommendation | The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend HBV vaccination for all infants and adults.[35] | United States |

| 1992 | Hepatitis B | Vaccination of infants against hepatitis B reaches coverage in 31 WHO Member States as part of their vaccination schedules.[21] | ||

| 1992 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | A blood test is developed to effectively screen blood before it is transfused. This would rediuce the risk of hepatitis C through a blood transfusion to approximately 0.01%.[5] | |

| 1992 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves lamivudine to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 1993 | Hepatitis B | Policy | The World Health Organization starts recommending vaccination against hepatitis B virus.[36] | |

| 1994 | Hepatitis B | Policy | Hepatitis B vaccine becomes part of the routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States.[37] | United States |

| 1996 | Hepatitis C | Epidemic | The Egyptian Ministry of Health estimates that 15 to 20 percent of Egyptians are infected with hepatitis c virus. Similar to the experience of many countries including Italy, the epidemic is linked to a nationwide vaccination campaign, during which needles were re-used. Egypt continues to report the highest hepatitis C rate in the world.[7] | Egypt |

| 1996 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves alfa interferon (Roche- Roferon A) to treat hepatitis C.[5] | United States |

| 1996 | Hepatitis A | Medical development | The inactivated Hepatitis A vaccine Avaxim (Sanofi Pasteur) is introduced for immunization of adults and children 2 years and over. This virus inacivated vaccine is administered through intramuscular injection.[38] | |

| 1996 | Recommendation | The United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that the inactivated hepatitis A vaccine should preferentially be given to individuals at high risk of infection (travellers to countries with high or intermediate endemicity, men who have sex with men, injecting-drug users, patients with clotting-factor disorders) and patients with chronic liver disease who are prone to develop fulminant hepatitis A. It is also recommended to vaccinate children in communities with

high rates of disease, such as Alaska Natives, American Indians, selected Hispanic and religious communities.[39] || United States | ||

| 1997 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves consensus interferon (Amgen-now InterMune-Infergen) to treat hepatitis C.[5] | United States |

| 1997 | Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B | Medical development | Hepatitis A and B vaccine Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is first marketed. It is administered through intramuscular injection.[40] | |

| 1998 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves combination of Interferon and anti-viral drug Ribavirin (Schering’s Intron A plus ribavirin) for hepatitis C virus therapy. The combination is most effective in preventing HCV relapse rather than as an anti-viral agent.[8][5] | United States |

| 1999 | Hepatitis B | Program launch | 85 states, primarily high and middle income, implement the World Health Organization recommendation for universal childhood immunization against hepatitis B. However, the vaccine would remain unavailable in most of the poorest countries, which harbor the highest burden of the disease.[41] | |

| 2001 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves both pegylated interferon and the combination of pegylated interferon with ribavirin for hepatitis C virus therapy.[8][7] | United States |

| 2002 | Hepatitis B | By the end of this year, more than 2 billion doses of Hepatitis B vaccine have been administered.[42] | Worldwide | |

| 2003 | Hepatitis A | Medical development | Virosome-formulated vaccine[43] Epaxal (Crucell) is introduced in Europe.[33] | Europe |

| 2005 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves entecavir to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2006 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves telbivudine to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2006 | Medical development | Prison needle exchange programs are established or piloted in a number of countries around the world, including Switzerland, Germany, Spain, Moldova, the Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and Iran (NEP is based on the philosophy of harm reduction that attempts to reduce the risk factors for diseases such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.[7] | Switzerland, Germany, Spain, Moldova, the Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Iran | |

| 2007 | Organization | The World Hepatitis Alliance is founded.[7] | ||

| 2007 (April) | Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B | Medical development | The United States FDA approves Hepatitis A and B vaccine Twinrix for an accelerated dosing schedule that consists of three doses given within three weeks followed by a booster dose at 12 months.[44] Administered through intramuscular injection, adults and children usually receive the injection in the upper arm, and infants receive it in the upper thigh.[45] | United States |

| 2008 | Campaign | The World Hepatitis Alliance launches the first World Hepatitis Day on May 19, with a campaign called Am I Number 12?, referring to the statistic that, worldwide, one in every 12 people is living with a form of viral hepatitis.[7] | ||

| 2010 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves rapid antibody test OraQuick for hepatitis C virus detection. This test gives results in 20 minutes.[8] | United States | |

| 2010 | The Sixty-third World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization passes a viral hepatitis resolution, recognizing, among other points, “the need to reduce incidence to prevent and control viral hepatitis, to increase access to correct diagnosis and to provide appropriate treatment programmes in all regions. In the same year, the WHO endorses July 28th as World Hepatitis Day, making it the fourth official global health awareness day, alongside HIV, malaria and tuberculosis.”[7] | |||

| 2011 | Hepatitis E | Medical development | A recombinant hepatitis E vaccine is licensed in China, for use in people ages 16–65 years old.[37] | People's Republic of China |

| 2011 | Program launch | In response to the Resolution on Viral Hepatitis, the World Health Organization establishes a Global Hepatitis Program.[7] | ||

| 2011 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves new oral agents boceprevir and telaprevir for the treatment of hepatitis C, in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. These new, triple-therapy regimens would cure rates as high as 70 to 75 percent. Therapy would last from 24 to 48 weeks.[46] | United States |

| 2012 | Hepatitis B | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves tenofobir to treat hepatitis B.[4] | United States |

| 2012 | Hepatitis E | Medical development | The first vaccine for hepatitis E (HEV 239 vaccine, Hecolin) is introduced in China for ages 16 and above. This recombinant vaccine contains hepatitis E virus (HEV)-like particles prepared using a recombinant Escherichia coli expression system.[47][48][49] | China |

| 2013 | Hepatitis C | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves sofosbuvir (sold under the brand name Sovaldi) and simeprevir (sold under the brand name Olysio) for the treatment for hepatitis C virus therapy.[8] | United States |

| 2014 | Hepatitis B | Vaccination of infants against hepatitis B reaches coverage in 184 WHO Member States as part of their vaccination schedules and 82% of children in these states receive the hepatitis B vaccine.[21] | ||

| 2015 | Hepatitis B | Publication | The World Health Organization launches its first Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons living with chronic hepatitis B infection. The recommendations:

| |

| 2015 | Hepatitis B | Scientific development | A Canadian paper describes using a mouse model of chronic hepatitis B infection and shows that interfering with certain proteins can facilitate clearance of the virus, which may have implications for human disease.[50] | Canada |

| 2016 (May) | Program launch | The World Health Assembly adopts the first “Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016-2021”, a strategy with the purpose to highlight the critical role of universal health coverage and set targets that align with those of the Sustainable Development Goals.[51] | ||

| 2016 | Hepatitis E | Medical development | The United States government recruits participants for the phase IV trial of the drug Hecolin, for the treatment of hepatitis E.[52] | United States |

| 2017 (August) | Policy | The American Academy of Pediatrics issues a policy stating that newborns should routinely receive hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth.[53] | United States | |

| 2017 (November 9) | Hepatitis B | Medical development | United States FDA licenses hepatitis B vaccine Heplisav-B (Dynavax), for use in adults age 18 and older.[54] | United States |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

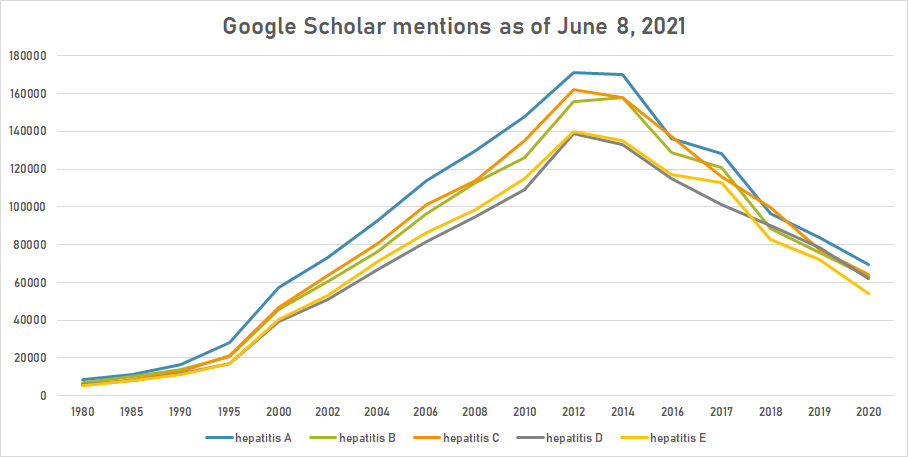

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of June 8, 2021.

| Year | hepatitis A | hepatitis B | hepatitis C | hepatitis D | hepatitis E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 8,730 | 6,800 | 5,300 | 5,800 | 5,580 |

| 1985 | 11,300 | 10,200 | 8,530 | 8,050 | 8,140 |

| 1990 | 16,700 | 13,900 | 12,700 | 11,600 | 11,300 |

| 1995 | 28,200 | 20,600 | 21,400 | 17,200 | 17,000 |

| 2000 | 57,500 | 45,400 | 46,900 | 39,300 | 40,300 |

| 2002 | 73,100 | 60,200 | 63,600 | 50,800 | 52,900 |

| 2004 | 92,900 | 76,200 | 80,800 | 66,600 | 71,000 |

| 2006 | 114,000 | 96,600 | 101,000 | 81,800 | 86,300 |

| 2008 | 130,000 | 113,000 | 114,000 | 95,100 | 98,600 |

| 2010 | 148,000 | 126,000 | 135,000 | 109,000 | 115,000 |

| 2012 | 171,000 | 156,000 | 162,000 | 139,000 | 140,000 |

| 2014 | 170,000 | 158,000 | 158,000 | 133,000 | 135,000 |

| 2016 | 136,000 | 129,000 | 137,000 | 115,000 | 117,000 |

| 2017 | 128,000 | 121,000 | 116,000 | 101,000 | 113,000 |

| 2018 | 96,200 | 88,400 | 99,700 | 90,100 | 82,900 |

| 2019 | 83,700 | 76,000 | 77,600 | 78,500 | 72,200 |

| 2020 | 69,300 | 62,900 | 64,000 | 62,100 | 54,100 |

Google Trends

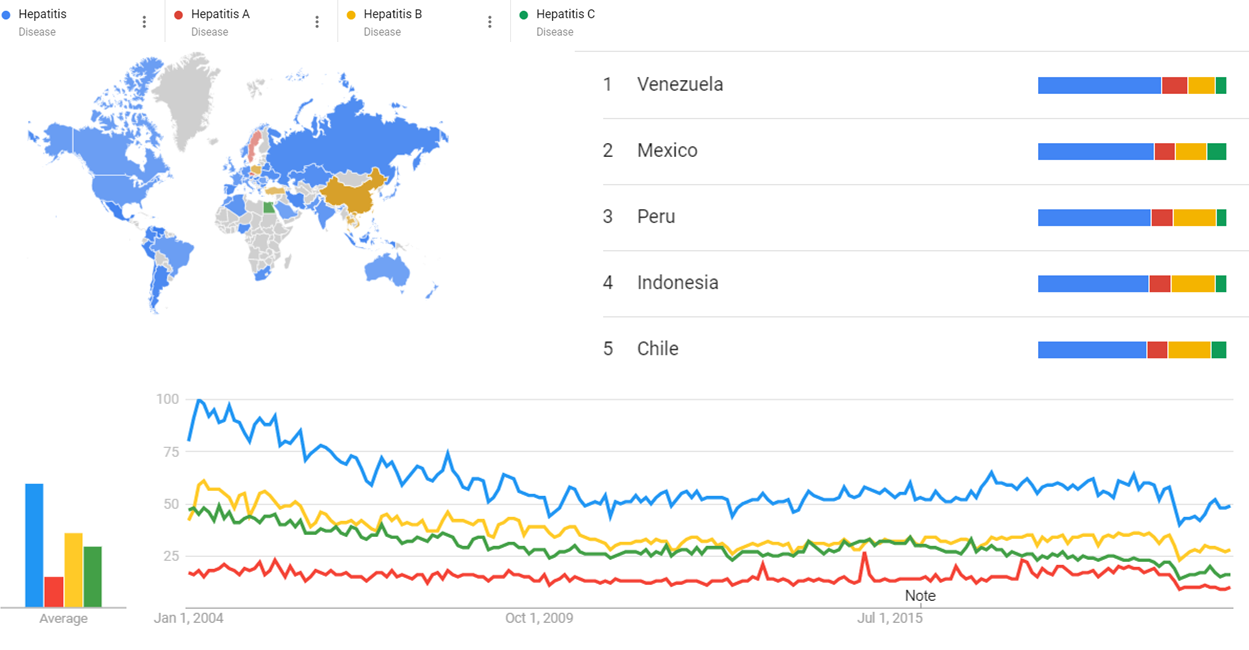

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Hepatitis (Disease), Hepatitis A (Disease), Hepatitis B (Disease) and Hepatitis C (Disease) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[55]

Google Ngram Viewer

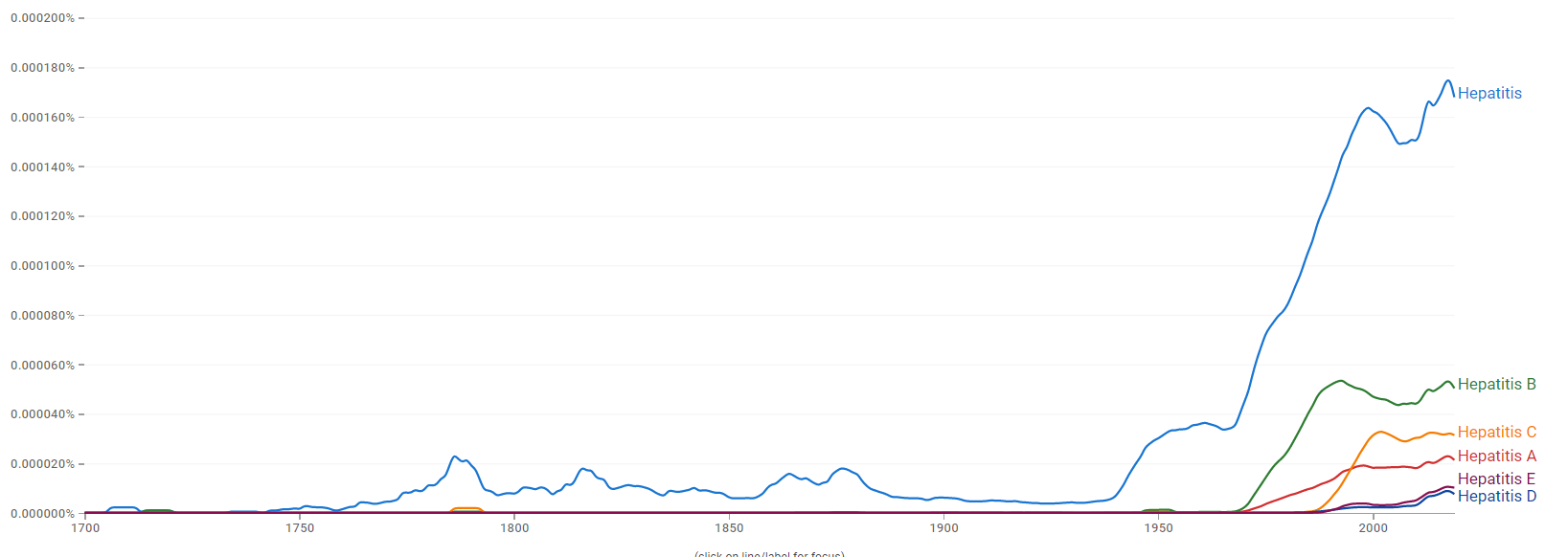

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Hepatitis,Hepatitis A,Hepatitis B,Hepatitis C,Hepatitis D and Hepatitis E, from 1989 to 2019. [56]

Wikipedia Views

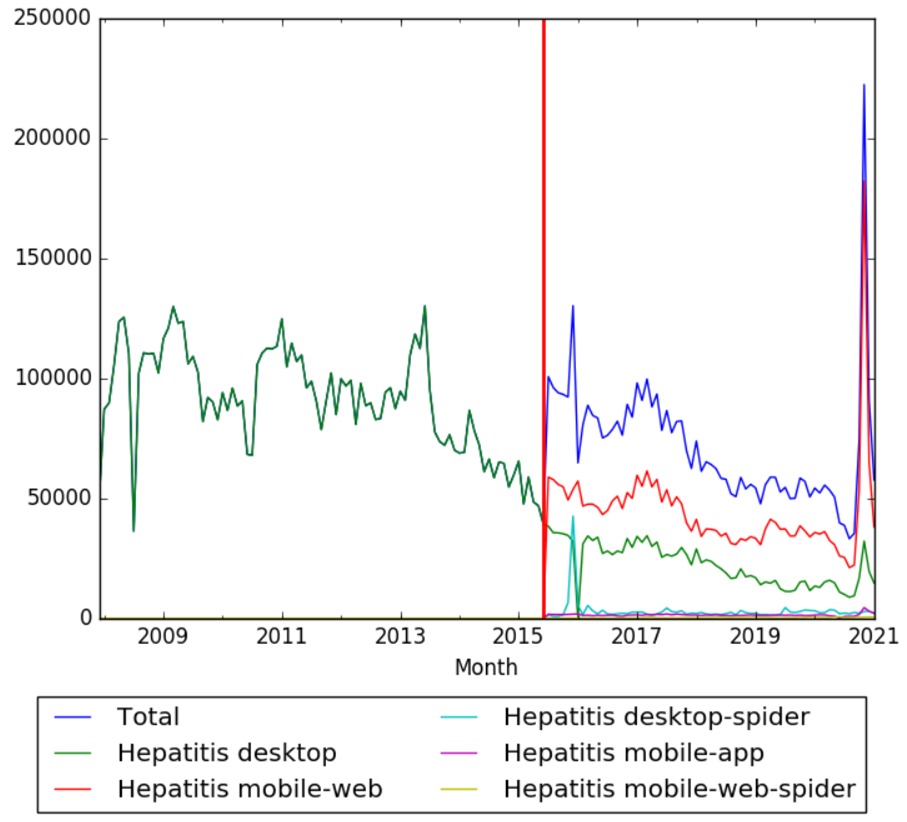

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Hepatitis, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app from July 2015; to January 2021.

See also

References

- ↑ "Viral Hepatitis B: Introduction" (PDF). hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The History of Hepatitis". stanford.edu. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Moore, Elaine A. Hepatitis: Causes, Treatments and Resources. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Thomas, Emmanuel; Yoneda, Masato; Schiff, Eugene R. "Viral Hepatitis: Past and Future of HBV and HDV". doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021345. ISSN 2157-1422. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Mandal, Ananya. "Hepatitis C History". news-medical.net. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Burns, Gregory S.; Thompson, Alexander J. "Viral Hepatitis B: Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics". doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024935. PMC 4292086.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 "A brief history of hepatitis C: 1989 - 2016". catie.ca. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 York Morris, Susan. "The History of Hepatitis C: A Timeline". healthline.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B: The Hunt for a Killer Virus". princeton.edu. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ MATHENY, SAMUEL C. "Hepatitis A". aafp.org. University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Datta, Sibnarayan; Chatterjee, Soumya; Veer, Vijay; Chakravarty, Runu. "Molecular Biology of the Hepatitis B Virus for Clinicians". doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.10.003. PMC 3940099.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Christian Trepo. "A brief history of hepatitis milestones". Liver International. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Baruch Blumberg, MD, DPhil". hepb.org. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ↑ Skwarczynski, Mariusz; Toth, Istvan (20 September 2016). Micro- and Nanotechnology in Vaccine Development. William Andrew. ISBN 978-0-323-40029-9.

- ↑ Hsieh, Ting-Hui; Liu, Chun-Jen; Chen, Ding-Shinn; Chen, Pei-Jer. "Natural Course and Treatment of Hepatitis D Virus Infection". doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60172-8. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ The politics of vaccination : a global history. Manchester. 2017. ISBN 978-1-5261-1088-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Khuroo, MS. "Discovery of hepatitis E: the epidemic non-A, non-B hepatitis 30 years down the memory lane". US National Library of Medicine. PMID 21320558.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "Hepatitis E Virus". doi:10.1159/000197321. PMC 2928833.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "The Rationale for Developing a More Immunogenic Hepatitis B Vaccine". vbivaccines.com. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B Foundation: History of Hepatitis B Vaccine". www.hepb.org. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Hepatitis B fact sheet". who.int. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Huzair, Farah; Sturdy, Steve (2017). "Biotechnology and the transformation of vaccine innovation: The case of the hepatitis B vaccines 1968–2000". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 64: 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.05.004. ISSN 1369-8486. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ↑ Services, Department of Health & Human. "Vaccine history timeline". www2.health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Coon, Lisa (2020-12-01). "The history of vaccines and how they're developed". OSF HealthCare Blog. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION" (PDF). merck.com. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ Bucci, Mirella (28 September 2020). "First recombinant DNA vaccine for HBV". Nature Research. doi:10.1038/d42859-020-00016-5. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ McCullers, Jonathan A.; Dunn, Jeffrey D. "Advances in Vaccine Technology And Their Impact on Managed Care". Pharmacy and Therapeutics. pp. 35–41. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ "Dosing Schedule for RECOMBIVAX HB® [Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant)]". MerckVaccines.com. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ Plotkin, Stanley A. (11 May 2011). History of Vaccine Development. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-1339-5.

- ↑ Services, Department of Health & Human. "Vaccine history timeline". www2.health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Vaccine Timeline and History of Vaccines". vaxopedia.org. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ "ENGERIX-B" (PDF). gskpro.com. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Patravale, Vandana; Dandekar, Prajakta; Jain, Ratnesh. Nanoparticulate Drug Delivery: Perspectives on the Transition from Laboratory to Market. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-908818-19-5.

- ↑ The Children's Vaccine Initiative: Achieving the Vision. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Children's Vaccine Initiative: Planning Alternative Strategies.

- ↑ Medicine, Institute of; Practice, Board on Population Health and Public Health; Vaccines, Committee to Review Adverse Effects of (26 April 2012). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-21435-3.

- ↑ "Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI)". who.int. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Bravo, Catherine; Mege, Larissa; Vigne, Claire; Thollot, Yael (4 March 2019). "Clinical experience with the inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, Avaxim 80U Pediatric". Expert Review of Vaccines. 18 (3): 209–223. doi:10.1080/14760584.2019.1580578.

- ↑ Plotkin, Stanley A. (21 September 2006). Mass Vaccination: Global Aspects - Progress and Obstacles. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-36583-9.

- ↑ "SB's Twinrix Launched In Its First Market - Pharmaceutical industry ne". www.thepharmaletter.com. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ New generation vaccines (3rd, rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. 2004. ISBN 9780203014158.

- ↑ Shoenfeld, Yehuda; Agmon-Levin, Nancy; Tomljenovic, Lucija (7 July 2015). Vaccines and Autoimmunity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-66343-1.

- ↑ Bovier, Patrick A (October 2008). "Epaxal ® : a virosomal vaccine to prevent hepatitis A infection". Expert Review of Vaccines. 7 (8): 1141–1150. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.8.1141.

- ↑ "FDA approves Twinrix". News-Medical.net. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ "Twinrix Intramuscular: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Pictures, Warnings & Dosing - WebMD". www.webmd.com. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C: A 21st Century Success Story (Op-Ed)". livescience.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Cao Y, Bing Z, Guan S, Zhang Z, Wang X (2018). "Development of new hepatitis E vaccines". Human Vaccine & Immunotherapics. 14 (9): 2254–2262. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1469591. PMID 29708836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "WHO | Hepatitis E vaccine". WHO. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E Vaccine: Composition, Safety, Immunogenicity and Efficacy" (PDF). who.int. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ Ebert, Gregor; Preston, Simon; Allison, Cody; Cooney, James; Toe, Jesse G.; Stutz, Michael D.; Ojaimi, Samar; Scott, Hamish W.; Baschuk, Nikola (2015-05-05). "Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins prevent clearance of hepatitis B virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (18): 5797–5802. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502390112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4426461. PMID 25902529. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E". www.who.int. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ "Phase Ⅳ Clinical Trial of Recombinant Hepatitis E Vaccine(Hecolin®) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "Give first dose of HepB vaccine within 24 hours of birth: AAP". aappublications.org. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ↑ "Summary Basis for Regulatory Action". fda.gov. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A, B & C". Google Trends. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ "Hepatitis,Hepatitis A,Hepatitis B,Hepatitis C,Hepatitis D,Hepatitis E". books.google.com. Retrieved 14 March 2021.