Timeline of stroke

This is a timeline of stroke, describing especially major discoveries, developments and organizations concerning the disease.

Big picture

Ancient times

Greek physician Hippocrates first recognizes stroke more than 2,400 years ago, calling the condition apoplexia. Hipocrates doesn't clarify that the condition actually happens in the brain,[1] instead resolving into a "stagnation of the blood, whereby all the motion and action of the spirits is taken away", and that the motion is stopped by sharp humours, or a plethora (an excess of red blood cells or bodily humours). Galen (129 AD) accepts and develops the theory of Hippocrates, believing that apoplexy is caused by anything interfering with the flow of the vital spirit to the brain. The galenic theory persists for centuries.[2]

Early modern times

British physician William Harvey (1578–1657) publishes his theory on the circulation of the blood. Others, like Wepfer (1620–1695), still believe that apoplexy is caused by an obstruction in the path to the brain, suggesting that the brain did not receive enough "animal spirits". G.G.J. Robinson theorizes that there is a "plethora of fulness of blood", therefore bleeding is acceptable since it lessens the pressure on the "animal organs". Overall, the definition introduced by Hippocrates is still in use.[2]

1700s

Although remnants of old dogma persist, the foundations have been laid for apoplexy to shed some ancient traditions based on symptomatic presentation and to evolve into a vascular disease based on clinico–pathological and patho–physiological correlates. Bonet publishes Sepulchretum sive Anatomica Practica, which becomes a prominent resource for physicians during most of the 18th century.[3]

1800s

The earliest known stroke treatments start to happen, when surgeons begin performing surgery on the carotid arteries. Surgeons begin operating to reduce cholesterol buildup and remove blockages that could then lead to a stroke.[1] Reports of successful closures of injuries to the carotid arteries are documented.[4]

1900s

Early in the 20th century, most of the treatments for stroke patients are limited to rehabilitation after an acute stroke, and most patients are usually left with permanent and severe deficits.[4] In the 1950s new techniques and therapies are developed to explore and modify the internal processes of cerebrovascular disease.[2] In the 1960s carotid endarterectomy is greatly improved but is used mostly for stroke prevention and there is still no effective treatment after an acute stroke. In the 1970s aspirin is found to be very effective in stroke prevention. In the 1980s cigarette smoking is found to be a definite risk factor for stroke, and smoking cessation programs become very important. In the 1990s tissue plasminogen activator starts to be used for treatment of embolic or thrombotic stroke.[4]

2000s

Today, rapid diagnosis is crucial for immediate treatment.[4] Stroke remains the second most common cause of death worldwide, accounting for 6.7 million deaths in 2012.[5] From 1990 to 2010, the age-standardised incidence of stroke significantly decreased by 12% in high-income countries, and increased by 12% in low-income and middle-income countries. In the same period, mortality rates showed a significant decrease in all countries.[6]

Full timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 460 BC–370 BC | Development | Hippocrates first recognizes stroke and calls the condition apoplexia, which is a Greek term that stands for “struck down by violence.”[1][7] | |

| 1620–1695 | Discovery | Swiss pathologist Johann Jakob Wepfer discovers that something disrupts the blood supply in the brains of peopled who died from apoplexy. In some of these cases, there was massive bleeding into the brain. In others, the arteries were blocked.[1][7] | |

| 1679 | Book | Swiss physician Théophile Bonet publishes his Sepulchretum sive Anatomica Practica, a work that contains 3,000 autopsy cases, included 70 cases of apoplexy, being the most extensive collection of its time.[3] | Geneva, Switzerland |

| 1820 | Development | English physician John Cooke writes:

| |

| 1927 | Development | Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz successfully performs cerebral arteriograms for the study of cerebral tumors. For this work, Moniz receives the Nobel Prize in 1949.[4] | Portugal |

| 1928 | Development | Apoplexy is divided into categories based on the cause of the blood vessel problem. This leads to the terms stroke or "cerebral vascular accident (CVA)."[7] | |

| 1950 | Organization | The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is founded.[8] | Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A. |

| 1954 | Development | CAROTID endarterectomy is introduced as a procedure for the prevention of ischemic stroke distal to carotid-artery stenosis.[9] | |

| 1972 | Development | Xingnao Kaiqiao needling method is developed by Xue-min Shi for the treatment of stroke, especially ischemic stroke.[10] | China |

| 1973 | Development | Melodic intonation therapy is developed as a technique in order to help stroke patients regain speaking skills.[11] | Boston Veterans Affairs Hospital, Boston |

| 1974 | Development | The Glasgow Coma Scale is developed to be applied by emergency medical services to stroke or head injured patients.[12] | University of Glasgow, Scotland |

| 1975 | Development | Fugl-Meyer Assessment is developed and later becomes the most established stroke motor measure. It is recommended for use in stroke rehabilitative trials.[13][14] | |

| 1976 | Discovery | Canadian Henry Barnett discovers that aspirin can prevent strokes in people at high risk, and can prevent recurrences in people who have had strokes.[15] | Canada |

| 1980-1985 | Development | The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is developed as a research tool to allow consistent reporting of neurological deficits in acute-stroke studies, particularly the early trials of thrombolysis and putative neuroprotectants.[16] | |

| 1989 | Organization | The International Stroke Society is established.[17] | |

| 1990 | Development | Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS), is developed as a comprehensive instrument to assess stroke impairment.[18] | |

| 1990-1999 | Development | The Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS) is developed as a method for identifying potential stroke victims in a pre-hospital setting.[19] | |

| 1994 | Organization | The National Stroke Research Institute (Australia) is founded.[20] | Heidelberg, Victoria (Australia) |

| 1994 | Development | Magnetic resonance imaging is introduced for stroke diagnosis.[21] | |

| 1994 | Organization | UCLA Stroke Center is founded.[22] | Los Angeles, California |

| 1996 | Policy | The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approves use of tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of stroke.[4] | U.S.A. |

| 1996 | Organization | The Congressional Heart and Stroke Coalition is founded as a bipartisan group of senators and representatives in order to raise awareness about the prevalence and severity of cardiovascular disease and the importance of research, prevention and treatment.[23] | U.S.A |

| 1997 | Development | The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale is developed as a system used to diagnose a potential stroke in a pre-hospital setting.[24] | Cincinnati, U.S.A |

| 1998 | Development | The Face Arm Speech Test (FAST) method is developed to help detect and enhance responsiveness to stroke victim needs.[25] | United Kingdom |

| 1999 | Development | tPA drug, which can erase the effects of a stroke if administered within a few hours of the onset of symptoms, is approved for use.[15] | Canada |

| 2001 | Development | MERCI Retriever is designed as a medical device to treat ischemic stroke.[26] | University of California, Los Angeles |

| 2001 | Organization | The Canadian Stroke Network is founded.[27] | |

| 2001 | Organization | A stroke unit is established for the first time in China, in the Department of Neurology of Beijing Tiantan Hospital.[28] | Beijing |

| 2002 | Report | Stroke is found to be the sixth largest cause of disability at a worldwide level.[29] | |

| 2004 | Organization | The World Stroke Federation is established.[17] | |

| 2005 | Development | First use of embryonic stem cells in stroke research is performed.[30] | |

| 2006 | Organization | The World Stroke Organization is established through the merger of the International Stroke Society and the World Stroke Federation.[17] | Geneva, Switzerland |

| 2008 | Development | The Kurashiki Prehospital Stroke Scale is developed for identifying thrombolytic candidates in acute ischemic stroke.[31] | |

| 2016 | Discovery | Immediate aspirin after mini-stroke is found to substantially reduce risk of major stroke.[32] | Oxford University |

Numerical and visual data

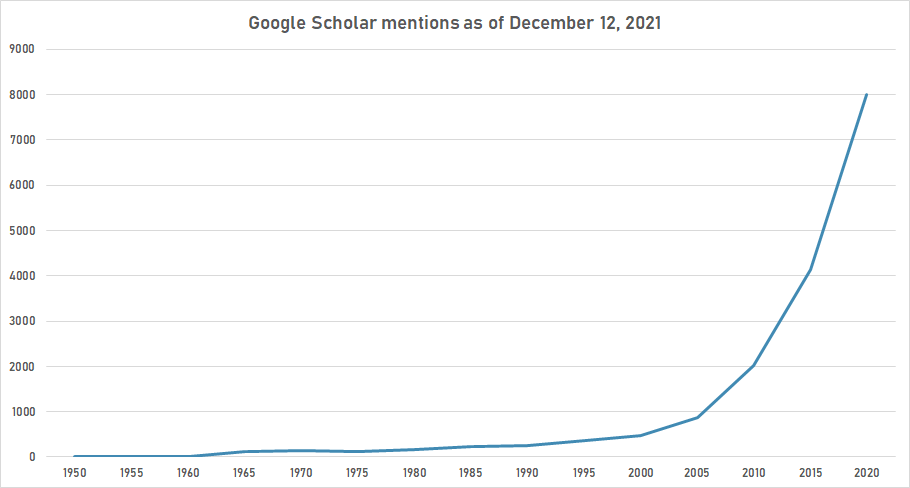

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 12, 2021.

| Year | stroke |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 1,700 |

| 1910 | 1,780 |

| 1920 | 1,890 |

| 1930 | 1,330 |

| 1940 | 1,300 |

| 1950 | 1,790 |

| 1960 | 3,320 |

| 1970 | 7,880 |

| 1980 | 14,300 |

| 1990 | 32,400 |

| 2000 | 146,000 |

| 2010 | 445,000 |

| 2020 | 176,000 |

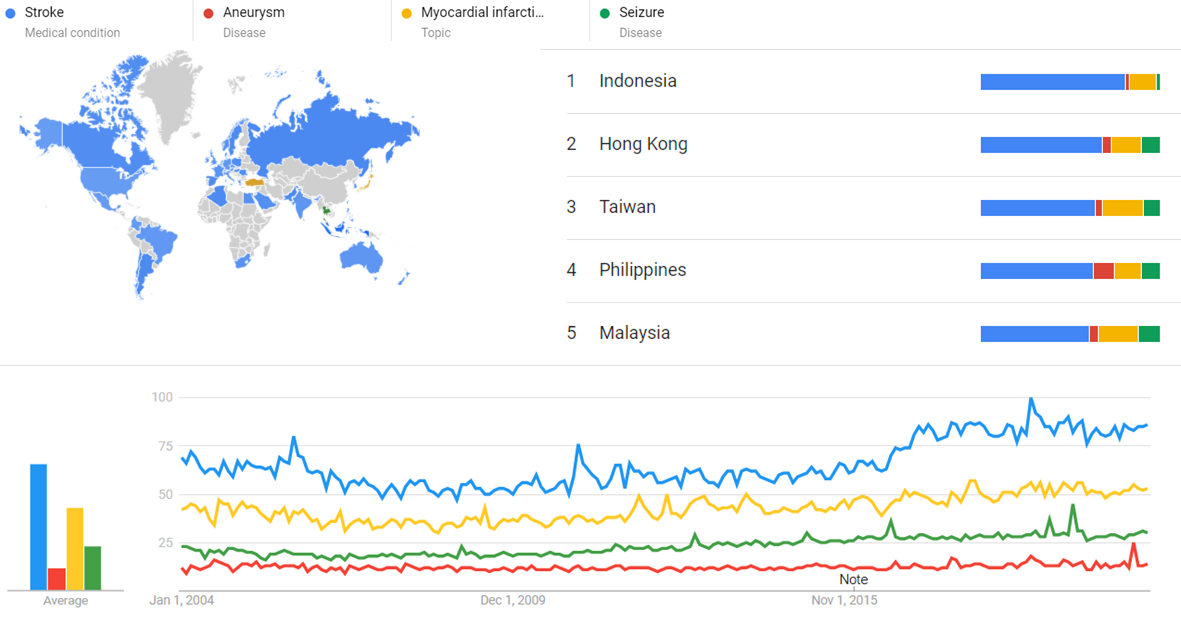

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Stroke (Medical condition), Aneurysm (Disease), Myocardial infarction (Topic) and Seizure (Disease), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[33]

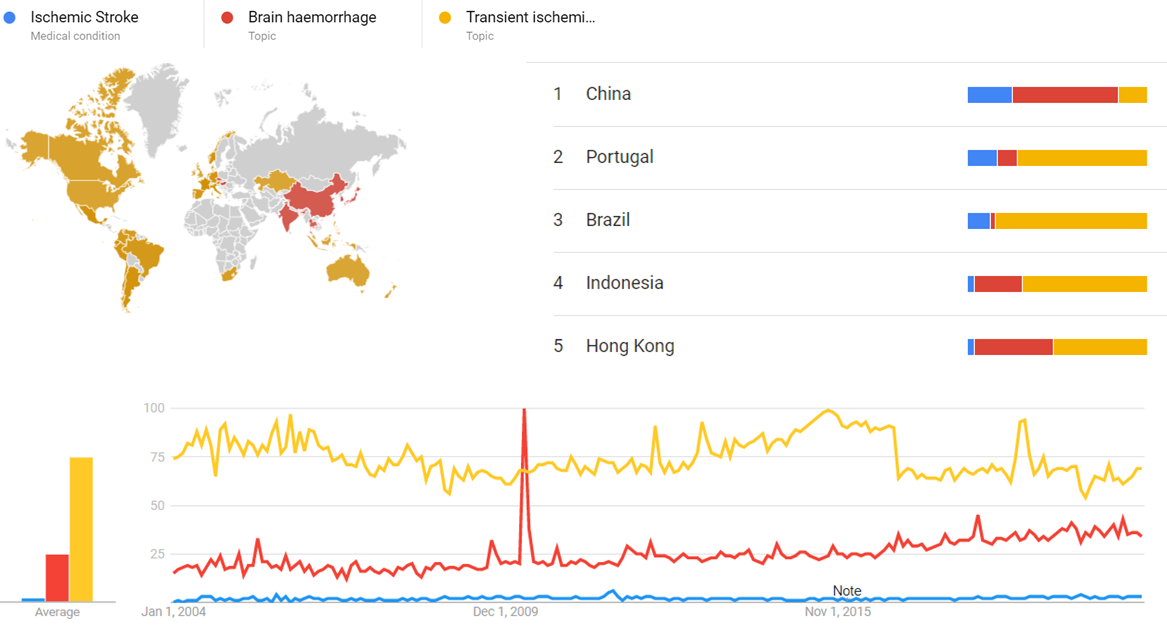

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Ischemic Stroke (Medical condition), Brain haemorrhage (Topic) and Transient ischemic attack (Topic), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[34]

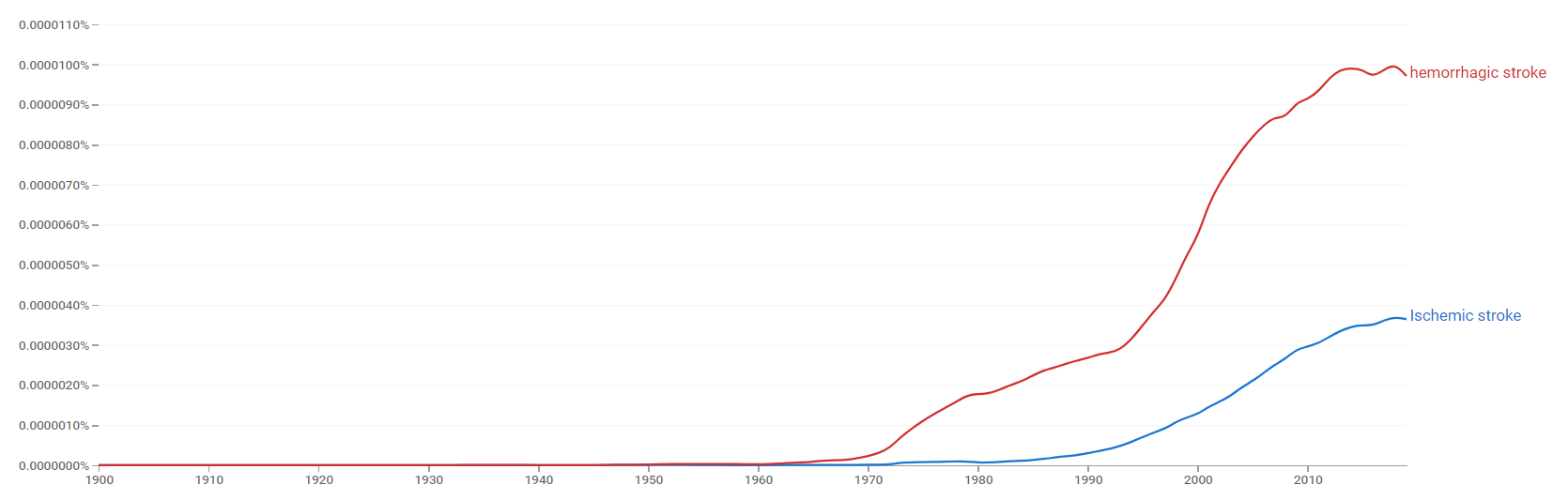

Google Ngram Viewer

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, from 1900 to 2019.[35]

Wikipedia Views

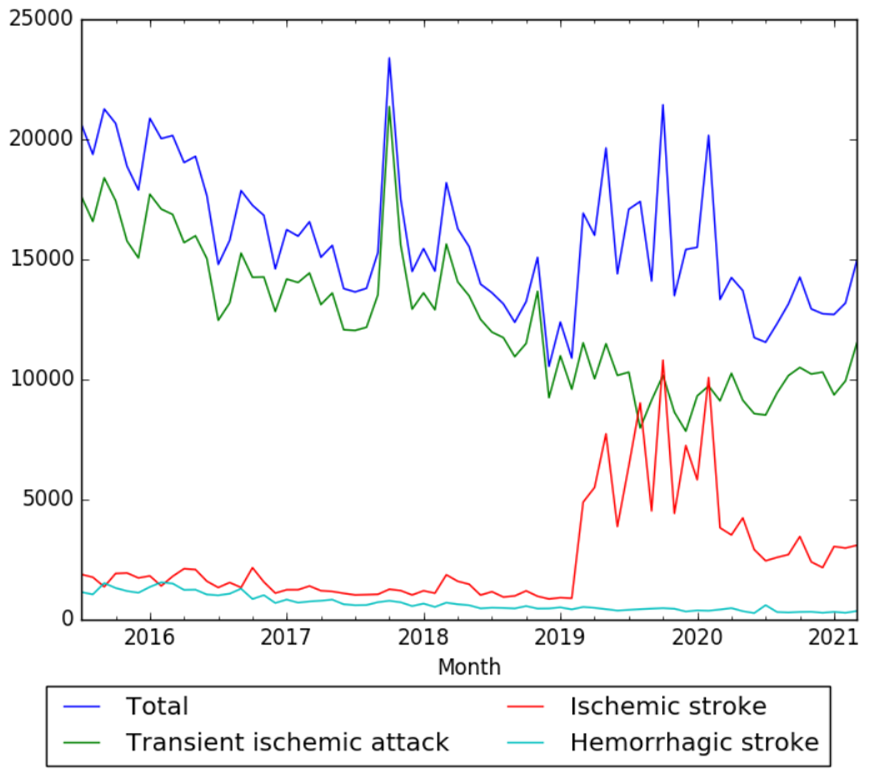

The comparative chart below shows pageviews on desktop of the English Wikipedia articles Ischemic Stroke, Hemorrhagic stroke, and Transient ischemic attack from July 2015 to March 2021.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "History of Stroke". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "From apoplexy to stroke" (PDF). Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Whitaker, Harry. Brain, Mind and Medicine:: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience. p. 237.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Stroke: Historical Review and Innovative Treatments". Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ↑ "The top 10 causes of death". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, Mensah GA, Connor M, Bennett DA, Moran AE, Sacco RL, Anderson L, Truelsen T, O'Donnell M, Venketasubramanian N, Barker-Collo S, Lawes CM, Wang W, Shinohara Y, Witt E, Ezzati M, Naghavi M, Murray C (2014). "Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 383 (9913): 245–54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4. PMID 24449944.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "History of Stroke". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ "NINDS". Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators (August 1991). "Beneficial Effect of Carotid Endarterectomy in Symptomatic Patients with High-Grade Carotid Stenosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 325: 445–453. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. PMID 1852179.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Systematic review of long-term Xingnao Kaiqiao needling effcacy in ischemic stroke treatment". Neural Regen Res. 10: 583–8. Apr 2015. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.155431. PMC 4424750. PMID 26170818.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ "Music Therapy Helps Some Regain Speech After Stroke". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ↑ Schwab, Stefan; Hanley, Daniel. Critical Care of the Stroke Patient. p. 66.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|subscription=(help) - ↑ Stephen J. Page, Peter Levine, Erinn Hade (2012). "Psychometric Properties and Administration of the Wrist/Hand Subscales of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment in Minimally-Impaired Upper Extremity Hemiparesis in Stroke". Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 93: 2373–6.e5. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.017. PMC 3494780. PMID 22759831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Sensorimotor Recovery After Stroke (FMA)". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "How Canadian scientists are changing the future". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Jennifer K Harrison, Katherine S McArthur, and Terence J Quinn (2013). "Assessment scales in stroke: clinimetric and clinical considerations". Clin Interv Aging. 8: 201–11. doi:10.2147/CIA.S32405. PMC 3578502. PMID 23440256.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "About WSO". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ Liu M1, Chino N, Tuji T, Masakado Y, Hase K, Kimura A. "Psychometric properties of the Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS)". Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 16: 339–51. doi:10.1177/0888439002239279. PMID 12462765.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Torbey, Michael; Selim, Magdy. The Stroke Book. p. 6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|subscription=(help) - ↑ "National Stroke Research Institute". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Lisa R. Leffert, Caitlin R. Clancy, Brian T. Bateman, MSc, Allison S. Bryant, Elena V. Kuklina (2015). "Hypertensive Disorders and Pregnancy-Related Stroke". Obstet Gynecol. 125: 124–31. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000590. PMC 4445352. PMID 25560114.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "UCLA Stroke Researcher Honored by American Stroke Association". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Congressional Heart and Stroke Coalition". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale" (PDF). Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Joseph Harbison, Omar Hossain, Damian Jenkinson, John Davis, Stephen J. Louw, Gary A. Ford. "Diagnostic Accuracy of Stroke Referrals From Primary Care, Emergency Room Physicians, and Ambulance Staff Using the Face Arm Speech Test". Stroke. 34: 71–76. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000044170.46643.5E.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "MERCI Story". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ Daniel S. Chow, Jason S. Hauptman, Tony T. Wong, Nestor R. Gonzalez, Neil A. Martin, Angella A. Lignelli, Michael W. Itagaki (2012). "Changes in stroke research productivity: A global perspective". Surg Neurol Int. 3: 27. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.92941. PMC 3307235. PMID 22439118.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ "Beijing Tiantan Comprehensive Stroke Center" (PDF). Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ "Different strokes". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ "Stroke: how could stem cells help?". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ Jang J, Chung SP, Park I, You JS, Lee HS, Park JW, Chung TN, Chung HS, Lee HS (2014). "The Usefulness of the Kurashiki Prehospital Stroke Scale in Identifying Thrombolytic Candidates in Acute Ischemic Stroke". Yonsei Med. J. 55: 410–6. doi:10.3349/ymj.2014.55.2.410. PMC 3936632. PMID 24532511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Immediate aspirin after mini-stroke substantially reduces risk of major stroke". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Stroke, Aneurysm, Myocardial infarction and Seizure". Google Trends. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ "Ischemic Stroke, Brain haemorrhage and Transient ischemic attack". Google Trends. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "Ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke". books.google.com. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Ischemic Stroke, Hemorrhagic stroke and Transient ischemic attack". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

Category:Stroke Category:Health-related timelines Category:Medicine timelines