Timeline of tetanus

This is a timeline of tetanus, atempting to describe major events such as scientific and medical developments concerning the disease.

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Ancient times < | Tetanus is first described in Egypt around 3000 years ago, and is considered to be prevalent throughout the ancient world.[1]. Tetanus would be a major menace and a master killer in all the wars during most of history.[2] |

| 1880s–1920s | Most crucial developments on the understanding and treatment of tetanus happen in this period, starting from the discovery of tetanus bacterium in 1884 until the first effective vaccine around 1923.[3][4] |

| 1930s < | Routine vaccination starts to be implemented in several countries.[5][6][7] The adoption of tetanus toxoid prophylaxis during World War II presents an opportunity to note the incidence of tetanus with and without active immunization and to some extent to compare success attained by different programs of immunization.[2] |

| 1980 < | The World Health Organization starts collecting data on diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus (DPT3) vaccination coverage. All regions apart from Americas and Europe are found to have a coverage under 20%. Since then, global coverage of DTP3 vaccination would increase steeply. By 2013 the lowest regional coverage stands at 75% in the WHO African Region and the global average at 86%.[8] |

| Recent years | Tetanus remains a public health problem in many parts of the world and is often fatal, even within modern intensive care facilities.[8] The disease remains a major health problem in the developing world and is still encountered in the developed world. Between 800000 and 1 million deaths due to tetanus are reported each year, of which approximately 400,000 are due to neonatal tetanus. Africa and South East Asia account for 80% of these deaths. Tetanus remains endemic in 90 countries world-wide.[1] |

Timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3000 BP | Early record | Tetanus is described in Egypt. The disease is thought to be prevalent throughout the ancient world.[9][1] | Egypt |

| 5th century BC | Early record | Records from these time contain descriptions of tetanus.[10][4] | |

| 1884 | Scientific development | Tetanus bacterium clostridium tetani is discovered when Italian scientists Giorgio Rattone and Antonio Carle first produce tetanus in animals by injecting them with pus from a human case.[10][11][12][4] | Italy |

| 1884 | Scientific development | Shortly after the advent of the germ theory of infectious diseases, German internist Arthur Nicolaier finds through experimentation with animals that tetanus is associated with bacilli of the soil. Nicolaier would produce tetanus in animals by injecting them with soil samples.[3][4] | Germany |

| 1889 | Scientific development | Japanese bacteriologist Shibasaburo Kitasato manages to isolate tetanus bacteria from an infected person, showing that they cause disease when injected into animals, and reports that the toxin could be neutralised by specific antibodies. This would be considered the first vaccine for passive immunology.[10][11][12][4] | Germany (Berlin) |

| 1890 | Scientific development | Danish researcher Knud Faber demonstrates the existence of a toxin by producing tetanus in animals injected with culture filtrates.[3] | Denmark |

| 1893 | Scientific development | French microbiologist and veterinarian Edmond Nocard demonstrates passive tetanus immunization by successfully treating with serum therapy and curing horses suffering from tetanus.[1] [11] | France |

| 1893 | Scientific development | French bacteriologist Pierre Paul Émile Roux and colleague L. Ann Vaillard, working at Pasteur Institute, attenuate the tetanus toxin by treatment with an iodine–potassium iodide solution.[3][13] | France |

| 1897 | Scientific development | Edmond Nocard demonstrates the protective effect of passively transferred antitoxin. Passive immunization in humans would be used for treatment and prophylaxis during World War I.[4] Passive tetanus profilaxis with equine antiserum is recognized as being able to prevent tetanus.[14][4][10] | |

| 1902 | Scientific development | Marie and Morax postulate the nervous pathway of transport of tetanus toxin. This would be demonstrated later by various investigators.[3] | |

| 1914 | Medical development | Anti-tetanus serum is introduced. This would be followed by an abrupt fall in tetanus incidence, even during World War I.[10][15] | |

| 1917 | Medical development | Vallé and Bazy carry out the vaccination of wounded during World War I with toxin detoxified by iodine treatment.[3] | |

| 1923 | Scientific discovery | French veterinarian and biologist Gaston Ramon reports the preparation of an antigenic toxoid by formaldehyde and heat treatment of the tetanus toxin. It would be considered the first inactive tetanus toxoid discovered and produced. The diphtheria and tetanus toxoid (TT), for which Ramon is considered their discoverer, are then referred to as anatoxins.[3][4]"[10][16][12][4] | France |

| 1923 | Scientific development | British immunologist Alexander Glenny perfects a method to inactivate tetanus toxin with formaldehyde.[17] | United Kingdom |

| 1924 | Medical development | Gaston Ramon student P. Descombey produces the tetanus toxoid that would be used in the United States military during World War II.[11][4] | |

| 1926 | Medical development | Gaston Ramon and Christian Zoeller successfully immunize human subjects with tetanus toxoid.[3][5] | |

| 1933 | Medical development | Fluid form of tetanus toxoid is licensed in the United States. Absorbed forms would follow later.[5] | United States |

| 1937 | Medical development | Tetanus toxoid is first licensed as a vaccine.[8] | |

| 1941 | Program launch | The first large-scale use of tetanus toxoid begins in the form of mass administration for American military forces. A record of tetanus toxoid doses administered is stamped on soldiers’ identification tags, as well as in paper records. In contrast, the German Army, relying on treatment with tetanus antitoxin, would suffer higher rates of morbidity and mortality from tetanus.[18] | |

| 1947 | Medical development | Combination diphtheria and tetanus toxoids for pediatric use is first licensed in the United States.[19][14] | United States |

| 1948 | Scientific development | Researchers first isolate the tetanus toxin in crystalline form.[3] | |

| 1953 | Medical development | Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids (adult formulation) are first licensed in the United States, after the concentration of diphtheria toxoid is reduced.[19] | United States |

| 1961 | Policy | Routine vaccination is implemented in the United Kingdom.[6] | United Kingdom |

| 1968 | Scientific development | Researchers first report the structure of the tetanus toxin.[3] | |

| 1968 | Policy | Italy introdouces routine vaccination against tetanus for all new-borns.[7] | Italy |

| 1974 | Program launch | Diphtheria toxoid combined with tetanus and pertussis vaccines (DTP) is included in the newly incepted World Health Organization Expanded Programme on Immunization.[20] | |

| 1975 | Scientific development | Soviet scientist Georgy N. Kryzhanovsky defines tetanus as a polysystemic disease due to the implication of many other organic systems in the effect of tetanus toxin, in addition to its prominent effect on the central nervous system.[3] | |

| 1980 | Program launch | The World Health Organization starts collecting data on diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccination coverage. All regions apart from the Americas and Europe are found to have coverage under 20%.[8] | |

| 1983 | Vaccine side effect | The first case of medium-vessel vasculitis related to vaccine exposure is described by Guillevin et al., who report an exacerbation of pulmonary manifestations in the course of polyarteritis nodosa following the administration of tetanus and BCG vaccines in a 19-year-old man.[21] | |

| 1989 | Program launch | The 42nd World Health Assembly calls for global neonatal tetanus elimination by 1995. Elimination is defined as less than one cases per 1,000 live births in every district of every country. The WHA goal would not be met.[10][22][1][6][23] | |

| 1990 | Program launch | The World Summit for Children lists neonatal tetanus elimination as one of its goals, and this goal is again endorsed by the 44th World Health Assembly.[23] | |

| 1996 | Medical development | Lederle Laboratories licenses diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, and acellular pertussis vaccine Acel-Imune, for use as the first through fifth doses in the series.[19] | |

| 1997 | Medical development | British pharmaceutical company SmithKline Beecham licenses Infanrix (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine adsorbed), for the first four doses of the series.[19] | |

| 1998 | Medical development | North American Vaccine Inc licenses Certiva (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine adsorbed), for boosting immunization of infants and children.[19] | |

| 1999 | Medical development | Connaught Laboratories licenses diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine Tripedia.[19] | |

| 1999 | Program launch | Progress towards the attainment of the global tetanus elimination goal is reviewed by UNICEF, WHO and UNFPA. This Initiative is re-constituted and elimination of maternal tetanus is added to the goal with a 2005 target date (later shifted to 2015).[23] | |

| 2000–2007 | An average of 31 cases in the United States is given in this period, with an all time low of 21 cases in the year 2003.[12] | United States | |

| 2002 | Medical development | British pharmaceutical GlaxoSmithKline licenses Pediarix, a vaccine combining diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio, and hepatitis B antigens.[19] | |

| 2002 | Medical development | Aventis Pasteur licenses diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine Daptacel.[19] | |

| 2004 | Medical development | Aventis Pasteur licenses vaccine Decavac, indicated for active immunization against tetanus and diphtheria.[19][24] | |

| 2011 | Medical development | United States Food and Drug Administration approves Boostrix (developed by GlaxoSmithKline) to prevent tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis in older people.[19] | United States |

| 2013 | The WHO African Region reports the highest number of non-neonatal tetanus cases at 4.0 per million population (3732 cases), followed by the South-East Asia Region at 1.9 per million population (3432 cases). Of the 12 African countries reporting any cases of non-neonatal tetanus, Uganda – the only country among them implementing voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention – would report the highest number of non-neonatal tetanus cases at 67.1 per million population (2522 cases).[8] | ||

| 2015 | Report | Neonatal tetanus remains a major public health problem in 23 countries: Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo DR, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Yemen.[25] | Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo DR, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen. |

| 2015 | Report | The World Health Organization estimates that 34,019 newborns died from neonatal tetanus, a 96% reduction from the situation in the late 1980s.[23] |

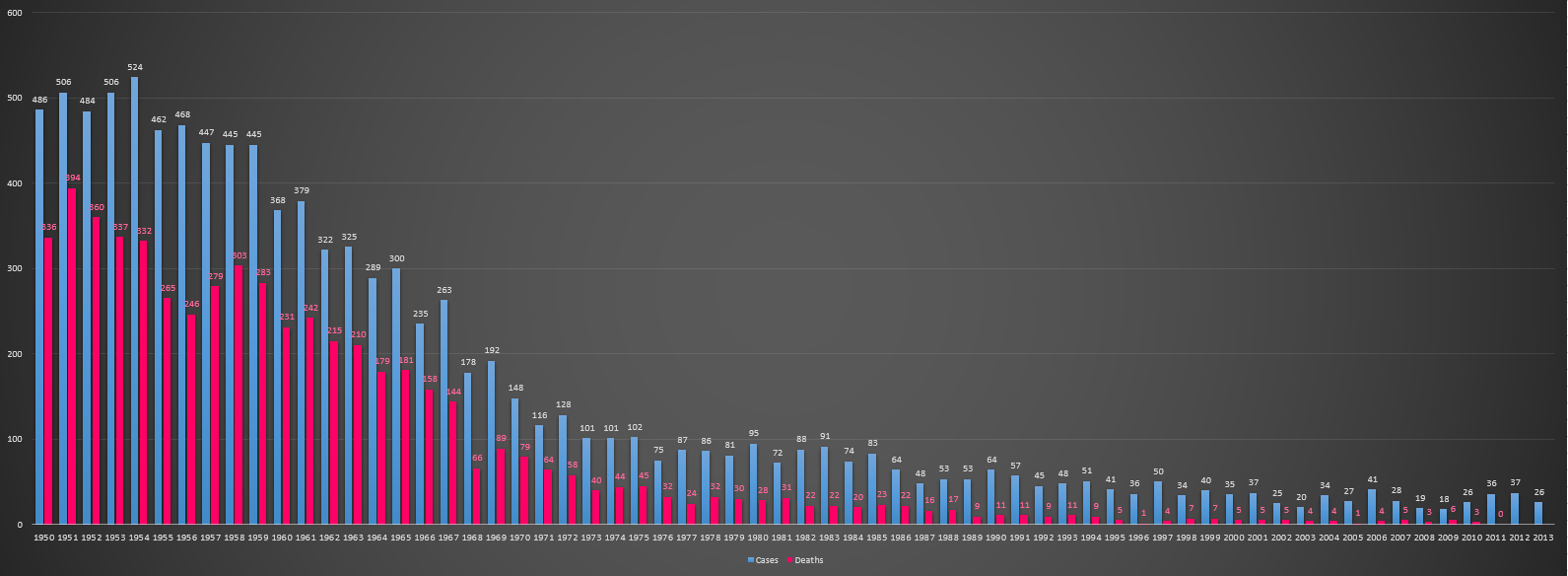

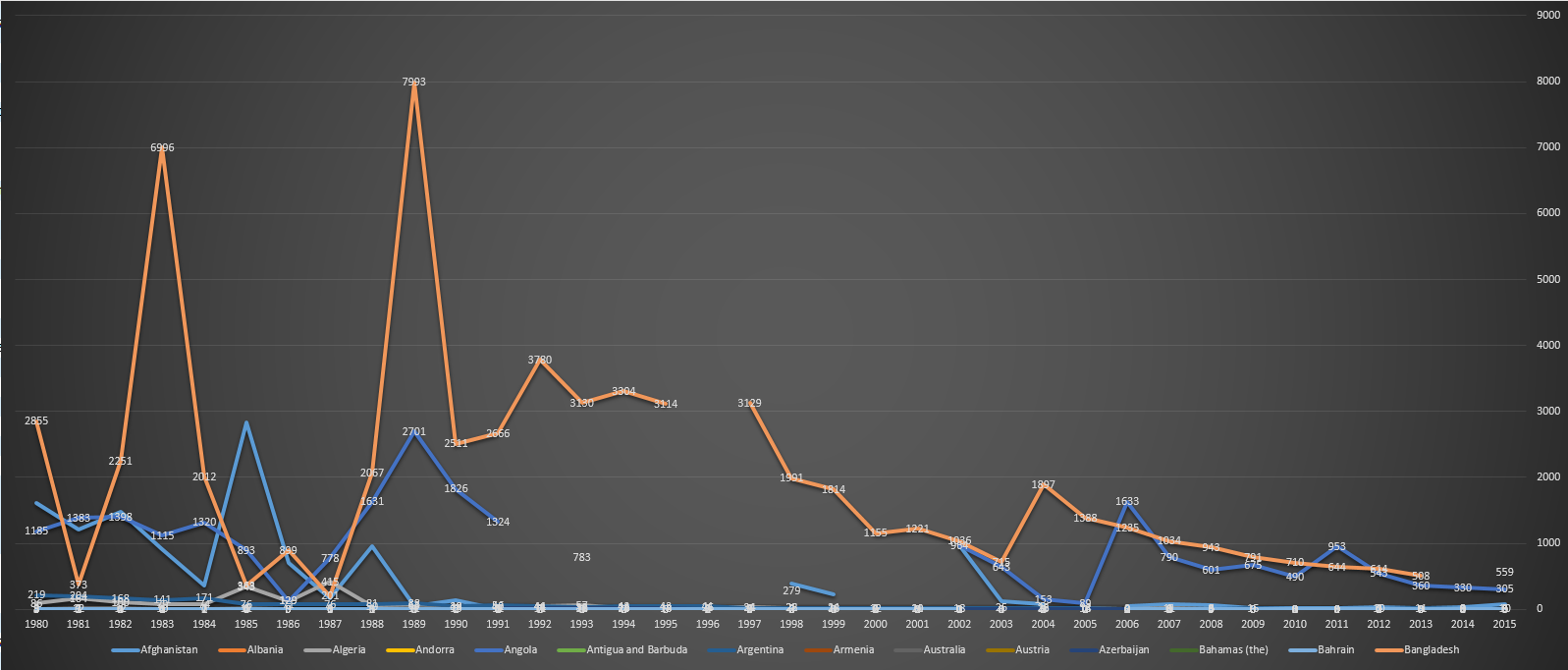

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

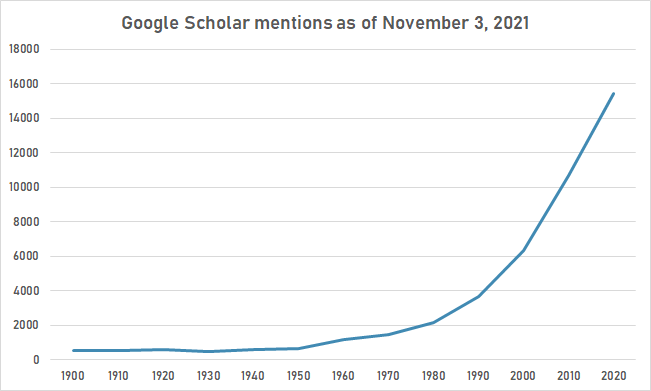

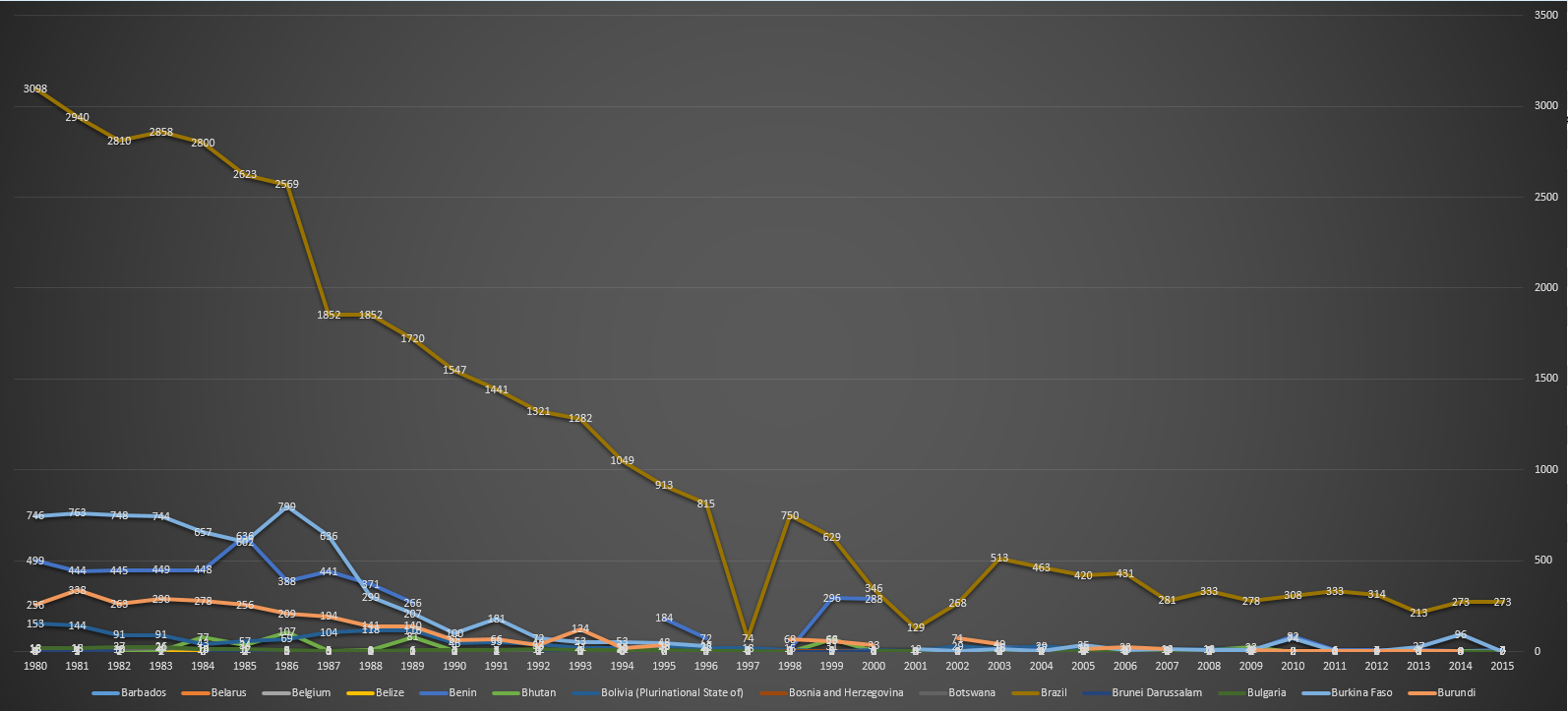

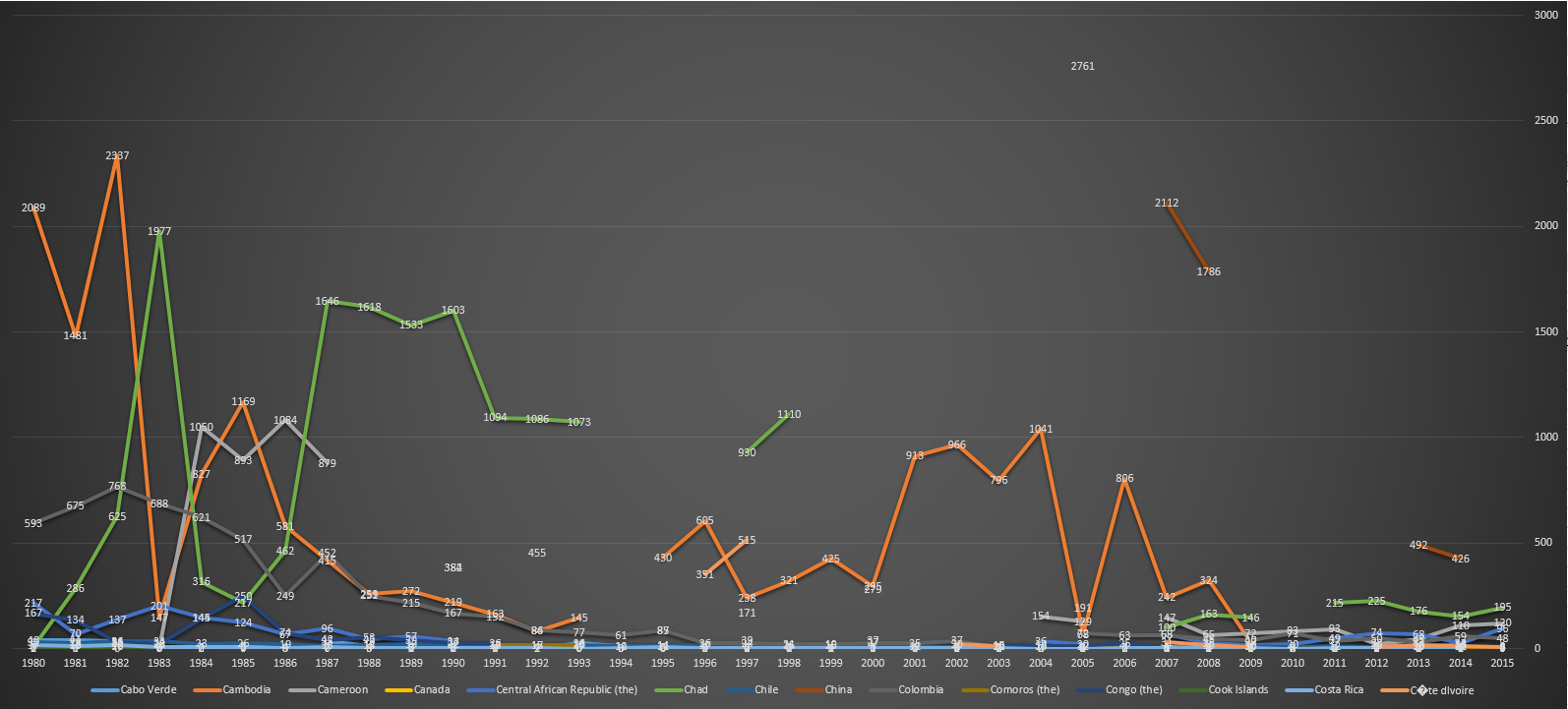

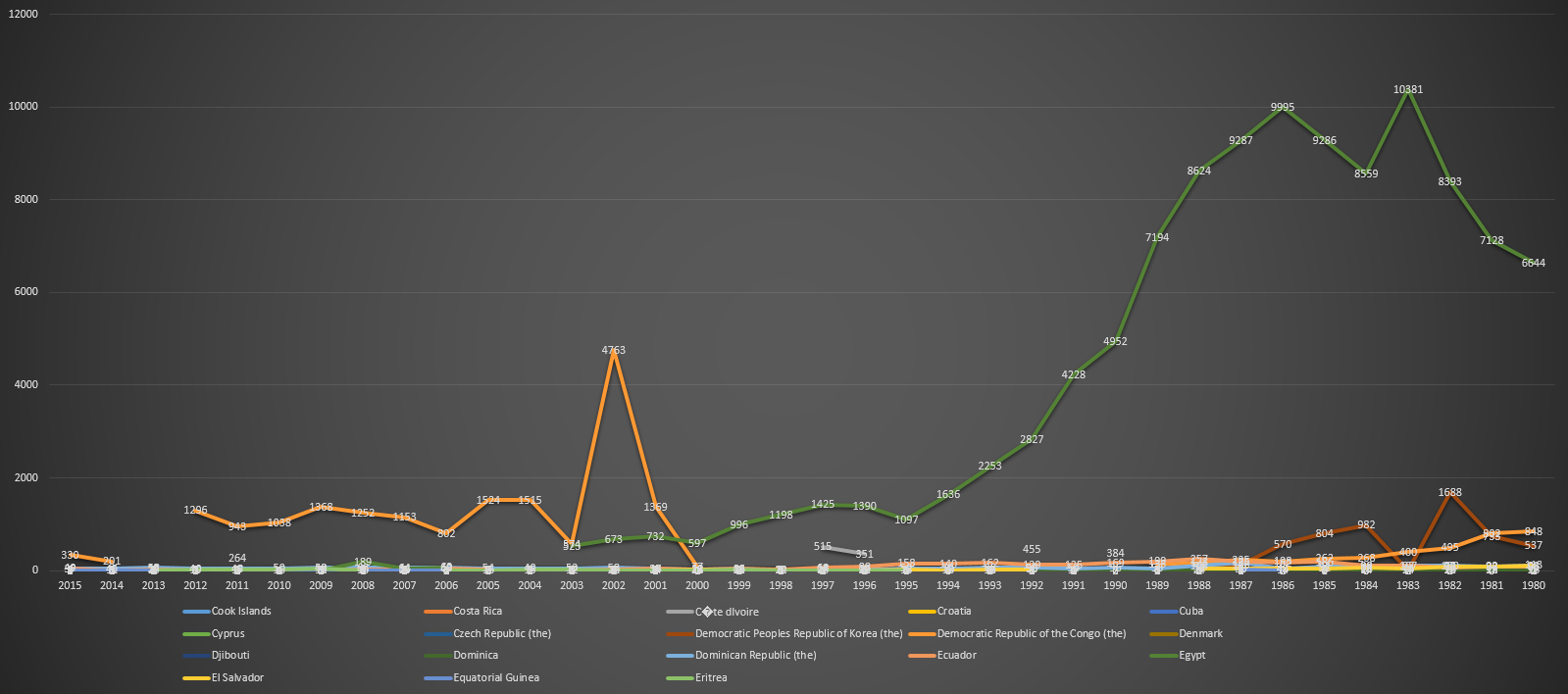

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of November 3, 2021.

| Year | Tetanus |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 544 |

| 1910 | 523 |

| 1920 | 592 |

| 1930 | 468 |

| 1940 | 605 |

| 1950 | 654 |

| 1960 | 1,180 |

| 1970 | 1,470 |

| 1980 | 2,170 |

| 1990 | 3,660 |

| 2000 | 6,330 |

| 2010 | 10,700 |

| 2020 | 15,400 |

Google Trends

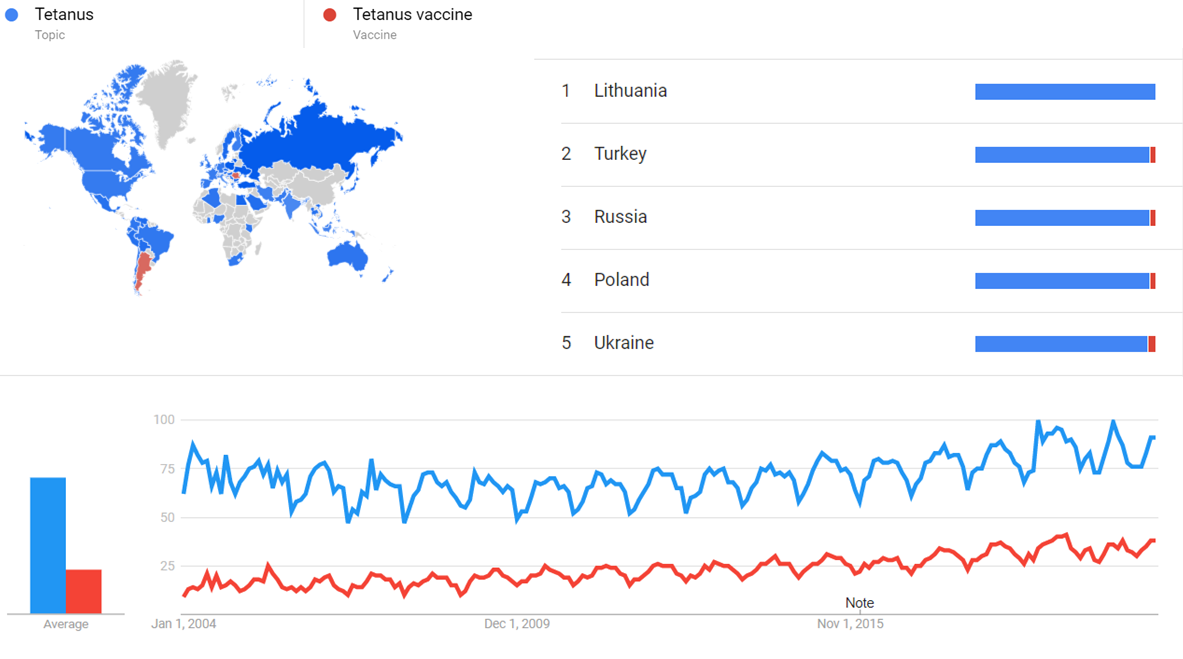

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Tetanus (Topic) and Tetanus vaccine (Vaccine), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[26]

Google Ngram Viewer

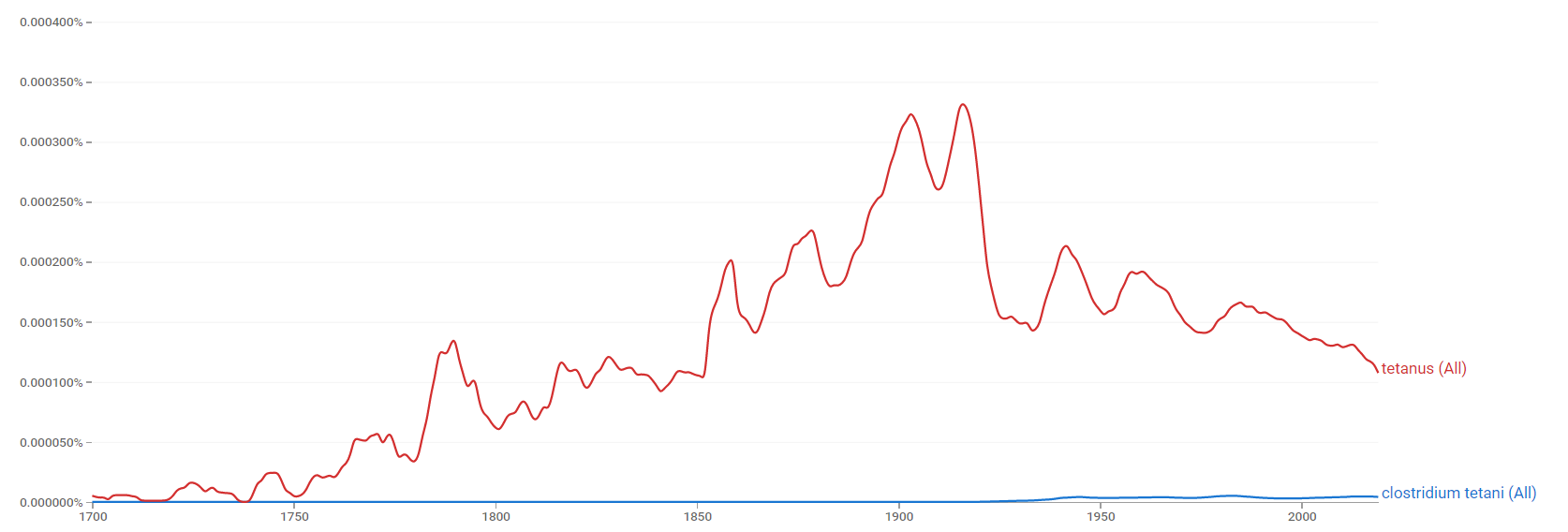

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Clostridium tetani and Tetanus, from 1700 to 2019.[27]

Wikipedia Views

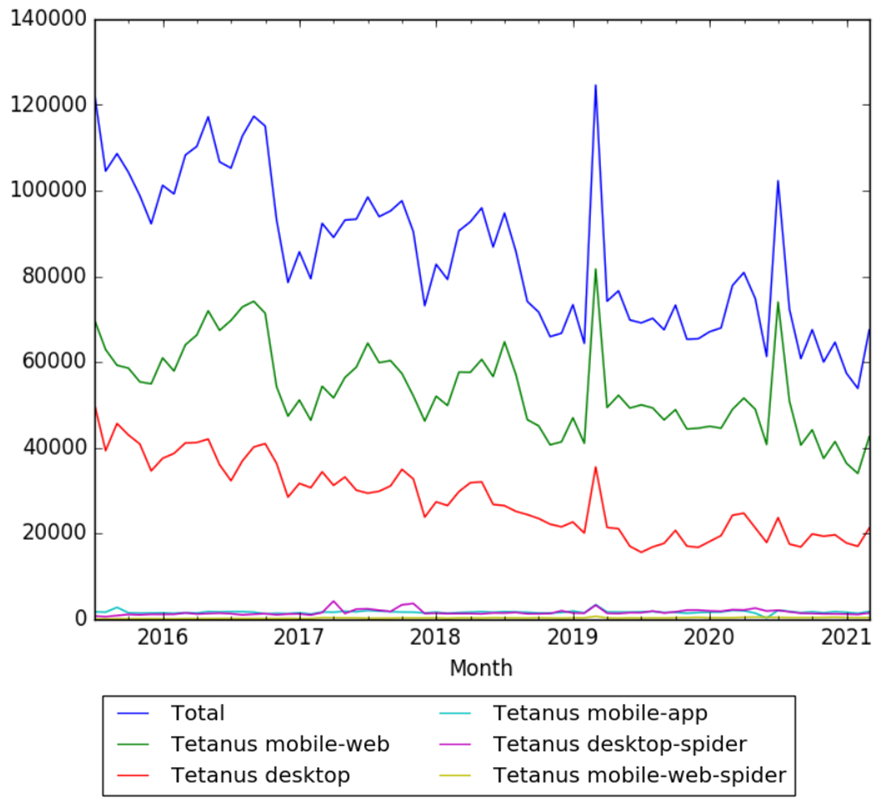

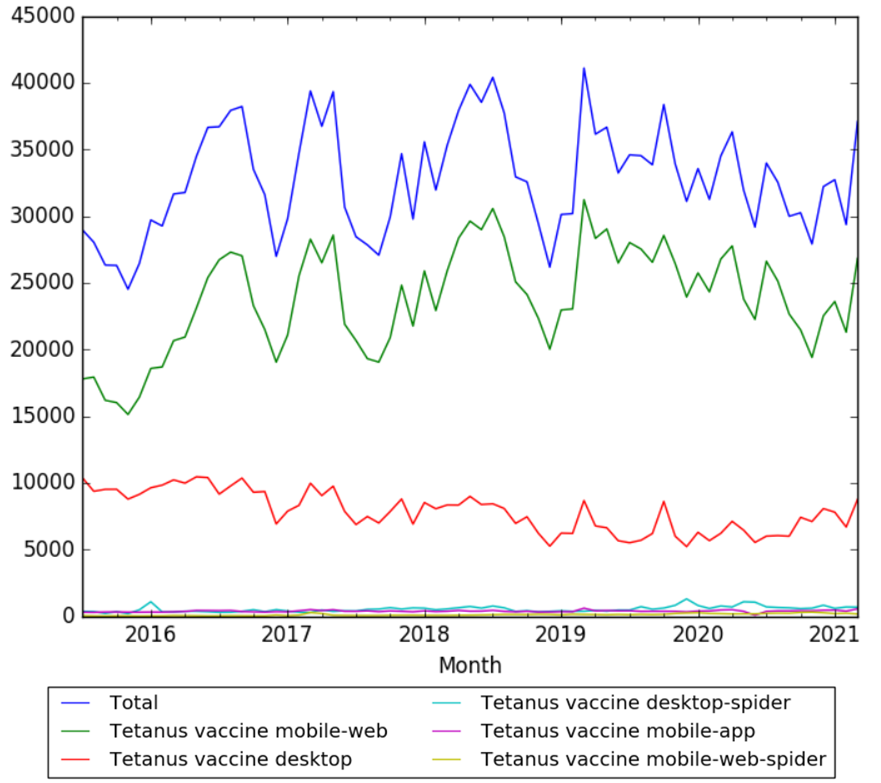

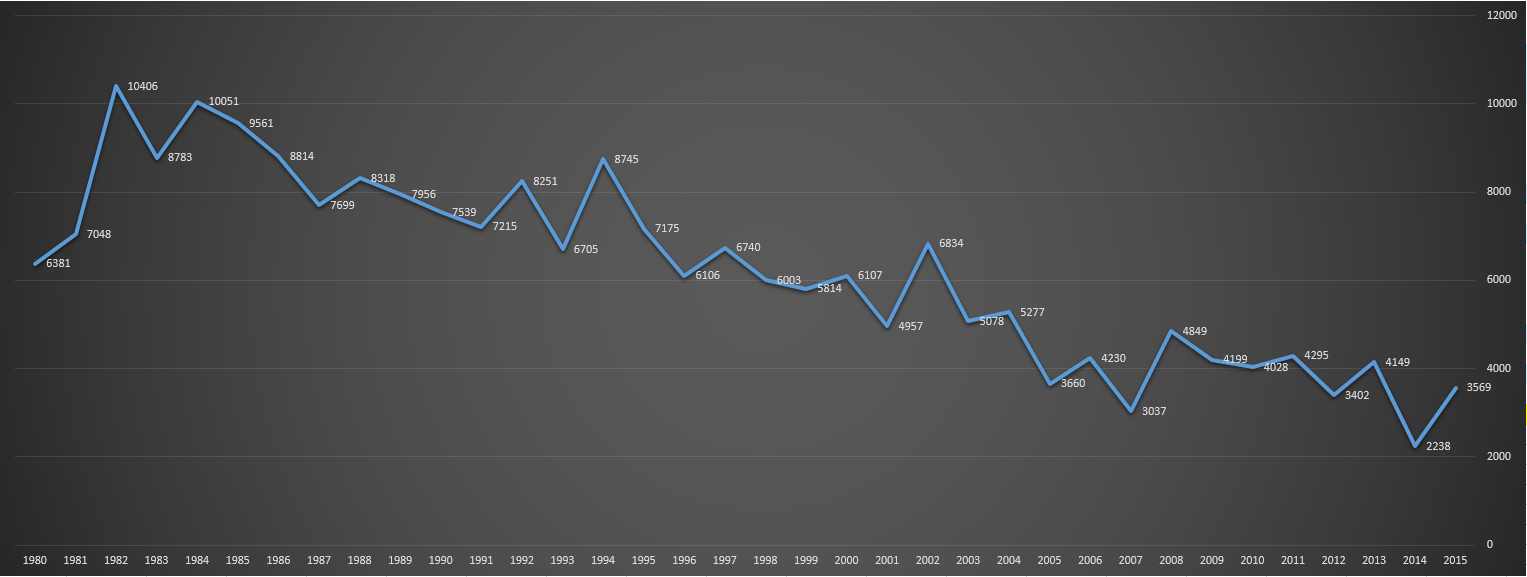

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Tetanus, from July 2015 to March 2021.[28]

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Tetanus vaccine, from July 2015 to March 2021.[29]

Other

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by FIXME.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

Pingbacks

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Clostridium tetani (Tetanus)". antimicrobe.org. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "THE U. S. NAVY'S WAR RECORD WITH TETANUS TOXOID(THE U. S. NAVY'S WAR RECORD WITH TETANUS TOXOID*)". annals.org. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Germanier, Rene. "Bacterial Vaccines". Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 "Tetanus" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Artenstein, Andrew W. Vaccines: A Biography. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Cook, T. M.; Protheroe, R. T.; Handel, J. M. "Tetanus: a review of the literature". oup.com. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Epidemiology of tetanus in Italy in years 1971-2000". eurosurveillance.org. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Tetanus disease and deaths in men reveal need for vaccination". US National Library of Medicine. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.166777.

- ↑ "Tetanus". BMJ Journals. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 "Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis: ancient diseases in modern times". pntonline.co.za. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Diphtheria, Tetanus (Lockjaw), and Pertussis (Whooping Cough) Cases and Deaths, and DTaP Vaccination Rates". procon.org. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Sanchez, Alexandra. "Tetanus". austincc.edu. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ The Anærobic Bacteria and Their Activities in Nature and Disease: Subject index. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Milligan, Gregg N.; Barrett, Alan D. T. Vaccinology: An Essential Guide. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "Prevention of tetanus during the First World War". US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ Medical Sciences - Volume I (B.P. Mansourian, S.M. Mahfouz, A. Wojtezak ed.). Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "A brief history of vaccination". immune.org.nz. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ↑ Plotkin, Stanley A. (21 September 2006). Mass Vaccination: Global Aspects - Progress and Obstacles. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-36583-9.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 "Vaccine Timeline". immunize.org. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ "Diphtheria". who.int. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ Shoenfeld, Yehuda; Agmon-Levin, Nancy; Tomljenovic, Lucija (7 July 2015). Vaccines and Autoimmunity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-66343-1.

- ↑ "Maternal immunization against tetanus" (PDF). who.int. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination (MNTE)". who.int. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION" (PDF). vaccineshoppe.com. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ "Vaccines for women for preventing neonatal tetanus". wiley.com. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ "Tetanus and Tetanus vaccine". Google Trends. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Clostridium tetani and Tetanus". books.google.com. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Tetanus". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Tetanus vaccine". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 21 April 2021.