Timeline of the technocracy movement

This is a timeline of the Technocracy movement, a socio-economic philosophy that advocates for governance by technical experts rather than politicians or market-driven systems. Emerging in the early 20th century, it was popularized by engineer Howard Scott and Technocracy Inc., proposing an energy-based economy where scientists and engineers would manage resources efficiently. The movement gained attention during the Great Depression, arguing that rational planning and technological advancements could eliminate waste and inequality. However, it declined due to political opposition and doubts about its practicality. Despite this, technocratic principles continue to influence modern debates on automation, AI governance, and data-driven decision-making in policymaking.

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What are some early examples of expert-led governance that foreshadow technocracy?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Historical precedent".

- You will see events illustrating historical precedents of technocracy. Each highlights early examples of expert-led governance, rational planning, and the pursuit of efficiency in statecraft.

- What are some key philosophical and scientific ideas behind technocracy?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Intellectual foundation".

- You will see events tracing the intellectual foundations of technocracy, from Laplace’s determinism and Saint-Simon’s expert-led visions to Wiener’s cybernetics and the Club of Rome’s modeling. Later theorists stressed organizational complexity and the tension between populist politics and expertise, highlighting evolving arguments for technocratic governance across centuries and contexts.

- What are some key events in the institutional development of the technocracy movement?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Institutional development".

- You will see a list of institutional developments, highlighting how ideas were formalized through organizations, schools, and committees, and illustrating the creation, spread, and influence of institutions that helped shape the broader movement over time.

- What are some major events and actions undertaken by the technocracy movement?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Movement activity".

- You will see events documenting activities, from early groups like the New Machine and Technical Alliance to Scott’s Technocracy Inc., public rallies, magazines, and conferences. They show the movement’s rise, fragmentation, decline, and persistence through spectacle, campaigns, bans, and postwar revival attempts.

- What are some examples of governments adopting technocratic principles?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Governance".

- You will see a number of events tracing technocracy’s role in governance worldwide, from Soviet central planning and Stalin’s repression of engineers to Singapore’s expert-led modernization, EU integration, and Marcos’s Philippines. Later examples include algorithmic decision-making, COVID-19 responses, and AI-driven governance. Together they show how technocratic principles shaped states, policies, and institutions across time.

- What are some important criticisms of technocracy across different decades?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Criticism".

- You will see a list of criticism-related events in the technocracy movement, including publications, official condemnations, and scholarly critiques, showing how opposition to technocracy evolved over time.

Big picture

| Time Period | Development Summary | More Details |

|---|---|---|

| 19th century – early 20th century | Intellectual foundations and early optimism | The 19th century is marked by a strong belief in the power of human reason to advance science and technology for the betterment of society. Thinkers like Frederick W. Taylor introduce scientific management, which influences the idea of a scientifically governed society. Writers such as Henry Gantt, Thorstein Veblen, and Howard Scott argue that business leaders are incapable of reforming industries for the public good, advocating for engineers to take control. This period sees widespread optimism about progress, with science and technology regarded as the primary drivers of societal change.[1][2] |

| 1930s | Rise of Technocracy | The Great Depression fuels discontent with traditional economic and political systems, creating fertile ground for the technocracy movement. Howard Scott and other advocates promote a vision of a "Technate of America," a scientifically managed North American government. Technocratic organizations spread across the United States and Canada, offering a utopian solution to unemployment and poverty by replacing politicians with engineers and technicians. However, the movement struggles to gain political traction as the New Deal and other third-party movements dominate public attention.[1][2] |

| 1940s – 1960s | Growth, transformation, and federal projects | Technocracy, Inc. emerges as a formal organization under Howard Scott, adopting a militaristic structure with uniforms and salutes. It gains visibility in cities like Los Angeles but faces criticism for its authoritarian undertones. Meanwhile, large-scale federal projects, such as the interstate highway system and the Apollo program, embody technocratic principles by using centralized planning and technological innovation to achieve national goals. The movement begins to decline as economic recovery and political stability reduce the appeal of technocratic ideals.[3][1] |

| 1970s – present | Decline and modern reflections | Crises like the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and oil shocks erode trust in technocratic leadership. By the mid-1970s, technocracy loses its influence and fades into obscurity. Technocracy, Inc. and similar organizations survive into the late 20th century but lack significant political impact. In the 21st century, technocratic ideas occasionally resurface in discussions about capitalism and technology. However, the movement remains a historical curiosity rather than a viable political force, and the vision of a fully realized technocracy has not materialized.[2][3] |

Full timeline

Inclusion criteria

We include:

- Notable pre-modern societies adopting governance practices, institutions, or reforms that clearly anticipate technocratic principles.

- Major organizations, schools, committees, or political coalitions being founded or reshaped around technocratic ideas. This covers formal bodies such as the Committee on Technocracy, political leagues, or academic institutions that advanced expert-led governance or promoted technocratic principles.

- Governance events including states or institutions applying technocratic principles through reforms, policies, appointments, or data-driven planning—whether successful, contested, or authoritarian.

- Notable publications that address technocracy or its core themes—scientific management, expert governance, efficiency, or the social impact of technology, including movement texts and utopian or dystopian works.

- Organized initiatives, reports, or proposals explicitly applying technocratic principles to reshape governance or economics.

We do not include:

- Notable events without reference dates.

- Minor organizations.

- Technocracy Inc complete publications.

Timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Century BCE | Historical precedent | Plato proposes a form of government where philosophers, trained in advanced reasoning, govern—an early form of technocracy. Plato’s idea of philosopher-kings, educated in wisdom and virtue, provide an early template, emphasizing governance by those with the deepest understanding of justice. Neo-Platonism would further influence technocratic thought, highlighting rationality and hierarchical expertise.[4] | Ancient Greece |

| c. 250 BCE | Historical precedent | The Library of Alexandria is established in Hellenistic Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty. Beyond being a center of knowledge, it becomes a hub for scientific inquiry, technical innovation, and bureaucratic management. Its scholars—many of whom were mathematicians, engineers, and physicians—played advisory roles to rulers, reflecting early forms of governance informed by expert knowledge.[5] | Ancient Egypt |

| c. 221 BCE | Historical precedent | The Qin Dynasty under Emperor Qin Shi Huang unifies China and implements a centralized bureaucratic state based on Legalist philosophy. Officials are selected for their administrative skill rather than birth, and standardized weights, measures, roads, and currency are introduced. This early merit-based bureaucracy prioritizes efficiency and uniformity, prefiguring technocratic statecraft.[6] | China |

| 1086 | Historical precedent | William the Conqueror commissions the Domesday Book, a massive survey of land, livestock, and resources in England. Created by royal bureaucrats and scribes using systematic methods, the Domesday Book exemplifies a proto-technocratic approach to governance through empirical data collection and centralized planning.[7] | England |

| 1453 | Historical precedent | After the conquest of Constantinople, Ottoman sultans increasingly employ technical specialists—astronomers, architects, and engineers—within the state apparatus. The famed architect Mimar Sinan, a civil engineer, designs major infrastructure and religious complexes under Suleiman the Magnificent, showing how technocratic talent shapes empire administration.[8] | Ottoman Empire |

| 1620–1626 | Historical precedent | English philosopher Francis Bacon publishes Novum Organum (1620) and New Atlantis (1626), envisioning a society governed by scientific advancement. In New Atlantis, he depicts a utopian society where knowledge and rational inquiry guide governance, foreshadowing modern technocratic ideals. Bacon’s influence would extend to the development of scientific institutions, such as the Royal Society, shaping Enlightenment thought and modern empirical science.[4][9] | England |

| 1703 | Historical precedent | Tsar Peter the Great founds the Russian Academy of Sciences, inviting foreign engineers, astronomers, and physicians to lead reforms. He emphasizes rational planning, infrastructure modernization, and expert-led statecraft, introducing European technocratic principles to Russia’s autocratic rule.[10] | Russia |

| 1801 | Intellectual foundation | French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace publishes A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, advocating that human behavior and natural events follow deterministic laws. His ideas would inspire the belief that societies can be governed through statistical reasoning and scientific forecasting—an early intellectual foundation for technocratic thinking.[14] | France |

| 1802 | Intellectual foundation | French political, economic and socialist theorist Henri de Saint-Simon proposes what would later be described as technocratic internationalism, consisting in a global order driven by industrial capitalism, led by scientists and engineers to ensure progress and harmony. He envisions governance through councils of technical experts, emphasizing large-scale engineering projects like canals to unite nations. Saint-Simon frames this system as apolitical, relying on science's neutrality, though it often reinforces existing social and racial hierarchies. His ideas, blending spiritual and rationalist dimensions, inspires disciples like Prosper Enfantin, who would advance mega-projects such as the Suez Canal. This perspective repositions Saint-Simon beyond proto-socialism, highlighting his pivotal role in technocratic and internationalist thought.[15] | France |

| 1820 | Intellectual foundation | Henri de Saint-Simon publishes L'Organisation, proposing a technocratic system where governance would be led by engineers, scientists, and industrialists rather than traditional politicians or aristocrats. He argues that decision-making should be based on scientific knowledge and technical expertise to ensure efficient management of society's resources. His ideas lay the foundation for technocratic thought, emphasizing economic planning, industrial progress, and the role of scientific elites in shaping policy. Saint-Simon’s vision would influence later socialist and technocratic movements, inspiring thinkers who seek to replace political rule with a more rational, expertise-driven system of governance.[16] | France |

| 1832 | Governance | The British Reform Act 1832 expands suffrage to include urban middle-class professionals, engineers, and industrialists. The act signals a shift from aristocratic to meritocratic representation, paving the way for increased political influence of scientifically educated elites during the Industrial Revolution.[17] | United Kingdom |

| 1870s | Historical precedent | The Meiji Restoration in Japan launches a state-led industrial revolution guided by Western-trained engineers and bureaucrats. The government builds railways, telegraph systems, and military arsenals through technocratic ministries like the Ministry of Industry. The reformers promote efficiency, data collection, and technical schooling—hallmarks of modern technocracy.[18] | Japan |

| 1888 | Publication | American author Edward Bellamy publishes Looking Backward, 2000–1887, a utopian novel about a future society in 2000 with nationalized industry, technological advances, and consumer convenience. Bellamy's book sparks the formation of over 160 Bellamyte societies in the U.S., blending populism, progressivism, and socialism. Bellamy critiques inefficiency and waste in capitalism, particularly in industrial management. He identifies four major wastes: mistaken undertakings, competition and hostility, crises and gluts, and idle capital and labor.[19] | United States |

| 1890 | Publication | British artist, writer, and socialist William Morris publishes News from Nowhere, a utopian novel that imagines a future society where capitalism has been replaced by a decentralized, cooperative commonwealth. In this vision, labor is no longer alienating but becomes a source of personal and communal fulfillment, deeply intertwined with art, beauty, and craftsmanship. Morris critiques industrial capitalism’s degradation of both human labor and the natural environment, proposing instead a world where manual work is pleasurable and socially valued. Although not explicitly technocratic, News from Nowhere challenges industrial society and resonates with later critiques of mechanized efficiency, offering a counterpoint to technocratic visions through its emphasis on human creativity and harmony with nature.[20] | United Kingdom |

| 1899 | Publication | Thorstein Veblen publishes Theory of the Leisure Class, a seminal work that critiques the inefficiencies of capitalism and the role of conspicuous consumption in society. Veblen argues that the economic elite prioritizes status and wealth accumulation over productive contributions to society. His analysis of industrial organization and technological potential deeply influences Howard Scott, the future leader of the Technocracy movement. Scott would adopt Veblen’s critique of profit-driven economies and expand on the idea that a scientifically managed system, rather than a market-based one, could optimize resource distribution and industrial efficiency for societal benefit.[21] | United States |

| 1904 | Publication | Thorstein Veblen publishes The Theory of Business Enterprise, which examines the conflict between profit-driven business interests and broader societal needs. He argues that while technological advancements improve efficiency and productivity, they also deepen social inequality. Veblen critiques the way businesses prioritize financial gain over public welfare, shaping economic structures that often hinder collective progress. His analysis aligns with technocratic ideals, as it highlights the tension between economic power and the potential for scientific and technological expertise to serve society more equitably. The book would remain a key work in economic theory, offering insight into the dynamics of capitalism and industrial development.[22][23][24] | United States |

| 1909 | Publication | Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti publishes the Futurist Manifesto, glorifying speed, machines, and industrial power. While not technocratic in structure, the movement inspires aesthetic and political visions centered on technological domination and elite-driven progress.[25] | Italy |

| 1911 | Publication | American mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor publishes The Principles of Scientific Management, introducing Taylorism—a system for optimizing work efficiency through systematic analysis and worker training. Taylor emphasizes data-driven decision-making and standardized practices to maximize productivity. The concept of a "technocrat" aligns with these principles, as technocrats would advocate for governance based on technical expertise and scientific methods. Both Taylorism and technocratic governance focus on efficiency, resource optimization, and evidence-based decision-making.[26][27] | United States |

| 1915 | Publication | American economist Horace Drury publishes Scientific Management: A History and Criticism, the first comprehensive academic study of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s system of scientific management. The book analyzes efforts to increase labor efficiency through measurement, task standardization, and managerial oversight. Drury underscores scientific management as a central challenge for modern industry, highlighting its potential to reduce waste and increase productivity. By framing it as a transformative force, he elevates its role in academic, political, and labor debates, while also laying foundations for later technocratic movements emphasizing expertise and rational planning.[19][28] | United States |

| 1917 | Governance | The Soviet Union is established following the Russian Revolution, marking the rise of a state heavily influenced by centralized economic planning. The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, seek to replace market-driven economies with a scientifically managed system, where production and distribution are controlled by the state. This approach resonates with technocratic principles, emphasizing expert-led governance and industrial planning. Soviet economic policies, particularly under Stalin, relied on five-year plans, prioritizing technological advancement and industrial efficiency. Although differing from Western technocratic movements, Soviet central planning reflects a belief in the power of scientific organization to manage society and economic development.[29][30] | Russia |

| 1918 | Movement activity | Engineer and management theorist Henry Gantt, alongside journalist and reformer Charles Ferguson, establish the "New Machine" society, a short-lived but influential political initiative advocating for a technocratic transformation of governance. Rooted in the belief that the existing profit-driven capitalist system is inefficient and socially harmful, the group proposes replacing it with a scientifically managed economy guided by engineers, planners, and technical experts. Gantt, known for his development of the Gantt chart and emphasis on industrial efficiency, brings a managerial perspective to the movement. Ferguson contributes a vision of rational organization and public service. The New Machine society criticizes private enterprise and champions centralized planning as a means to optimize production and align economic activity with public welfare.[19] | United States |

| 1919 | Institutional development | William Henry Smyth, a California-based inventor, engineer, and social reformer, first coins the term "technocracy" in his article “Technocracy – Ways and Means to Gain Industrial Democracy,” published in the Journal of Industrial Management. He defines technocracy as a system in which engineers and scientists play a key role in decision-making, aiming to achieve industrial democracy.[31][32] | United States |

| 1919 | Institutional development | Thorstein Veblen, along with Charles Beard and James Harvey Robinson, co-found The New School for Social Research to promote academic freedom and critical inquiry. Veblen, an economist and social theorist, applies an evolutionary approach to economic institutions, arguing that profit-driven limits on production leads to unemployment and economic inefficiencies. His critiques of consumerism and capitalism would become influential in the 20th century. Until 1926, he would contribute to the school's development while writing The Engineers and the Price System, where he proposes a technocratic "soviet of engineers." The institution would continue until today as The New School in New York City.[33][34] | United States |

| 1919 | Movement activity | Howard Scott, who would be called the "founder of the technocracy movement"[35], starts the Technical Alliance in New York, with mostly scientists and engineers as members. The Technical Alliance starts an Energy Survey of North America, which aims to provide a scientific background from which ideas about a new social structure can be developed.[36] However the group would break up in 1921[37] before the survey is completed.[38] The Technical Alliance would dissolve in the 1920s during the period of "normalcy" following World War I, without achieving significant impact. Howard Scott would continue to develop his ideas independently, allegedly uninfluenced by Thorstein Veblen.[39] | United States |

| 1921 | Publication | American economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen publishes The Engineers and the Price System, offering a critical analysis of industrial society and the inefficiencies of capitalism. He argues that engineers and technical experts, who understand industrial processes, are better suited to manage the economy than profit-driven business elites. Veblen critiques the price system for fostering artificial scarcity and planned obsolescence, which he sees as barriers to economic efficiency. He proposes a "soviet of technicians"—a technocratic governance model where engineers oversee production and distribution. Veblen suggests that technological advancements could facilitate a transition to a more rational, socialistic economic order. He is later associated with the Technical Alliance, a New York–based group of engineers and technocrats. The work lays intellectual groundwork for later technocratic movements, including that of Howard Scott.[40][41][42][31] | United States |

| 1922–1930s | Institutional development | Chinese intellectuals, including Luo Longji study at Columbia University and other institutions in the United States, where they are influenced by American technocratic ideals. Upon returning to China in the 1920s, they help introduce these concepts, which the Nanjing government later adopt as part of its political development strategy.[43] | China, United States |

| 1927 | Publication | Metropolis by Fritz Lang is released, portraying a futuristic city governed by technocrats who control energy and labor. The film is among the earliest cinematic critiques of technocracy, contrasting elite technical control with working-class rebellion.[44] | Germany |

| 1929 | Publication | Aldous Huxley publishes Machinery, Psychology, and Politics, a work in which he argues that the modern machine age necessitates a highly efficient, factory-like political organization. He suggests that traditional political structures are inadequate for managing the complexities of an industrialized society and that governance should adopt rational, systematic, and mechanized approaches, akin to factory management. Huxley’s ideas reflect broader technocratic sentiments of the time, which emphasize scientific management, expertise, and efficiency as essential components of political and economic systems in an increasingly industrialized world.[20] | United Kingdom |

| Post-1929 | Governance | In the years following the 1929 economic crisis, engineers and technical experts in the Soviet Union experience growing persecution under Joseph Stalin’s regime, particularly during the early 1930s purges. Accused of sabotage or counter-revolutionary behavior, many are imprisoned or executed during show trials like the 1930 Shakhty Trial. This repression forces surviving engineers to confine their work to narrowly defined technical roles dictated by the Communist Party, suppressing independent scientific thinking or system-wide reform proposals. At the same time, Soviet thinker Alexander Bogdanov develops the concept of Tectology, a proto-systems theory advocating for universal organizational principles. Tectology envisions the replacement of capitalist chaos with scientifically structured social systems, anticipating later technocratic ideals that prioritize planning, feedback, and coordination over politics.[45][46] | Soviet Union |

| 1931–1932 | Movement activity | M. King Hubbert, a young geophysicist, moves from Chicago to be an instructor at Columbia University. Hubbert meets Howard Scott in New York, becomes most impressed by his ideas and seeks to give them a more firm scientific basis. Hubbert pays Scott's back rent, moves in with him, and sets about reestablishing something like the old Technical Alliance, an attempt that would culminate in the Energy Survey of 1932.[47] | United States |

| 1932 | Program | The Technocracy Study Course is developed, outlining an energy-based economic model as an alternative to traditional monetary systems. The course, authored by Howard Scott and the Technical Alliance, proposes that economic value should be measured in energy units rather than currency, advocating for a society managed by technical experts rather than politicians. This model aims to maximize efficiency, eliminate waste, and ensure equitable resource distribution. The study course becomes a foundational document for the Technocracy movement, influencing debates on economic planning and governance while sparking both interest and controversy over its feasibility and implications for individual freedoms.[48][49] | United States |

| 1932 | Publication | Aldous Huxley publishes Science and Civilization, a critical essay that addresses the accelerating influence of science and technology on modern life. Huxley argues that while scientific progress has immense potential, it also poses serious risks if left unchecked by ethical considerations and humanistic values. He warns that a purely technical or mechanistic worldview can lead to social chaos, dehumanization, and the erosion of moral responsibility. Instead, Huxley advocates for the integration of scientific knowledge with philosophical and ethical reflection—a vision where science serves humanity rather than dominates it. This publication reflects broader contemporary anxieties about technocracy and the need to balance innovation with compassion and wisdom.[20][20] | United Kingdom |

| 1932 | Institutional development | The Committee on Technocracy is established in New York City, led by Walter Rautenstrauch and largely influenced by Howard Scott. Scott asserts that technological abundance will render traditional economic concepts based on scarcity obsolete and predicts the eventual collapse of the price system, which he believes will be replaced by a technocratic system.[2] | United States |

| 1932 | Movement activity | The term "technocracy" gains widespread public attention during the depths of the Great Depression. It garners media coverage and public fascination for its high-sounding terminology (e.g., "ergs," "extraneous energy," "social thermodynamics"). However, the furor is short-lived. Columbia University distances itself from Scott and the movement, as some of Scott's collaborators also withdraw.[39] | United States |

| 1932 | Publication | English writer Aldous Huxley publishes Brave New World, a dystopian novel that satirizes technocracy and totalitarianism. Set in a futuristic society governed by scientific and technological control, the novel explores themes of social engineering, consumerism, and the suppression of individuality. Huxley critiques the potential consequences of a highly organized, efficiency-driven world where human emotions, free will, and critical thought are sacrificed for stability and order. The book presents a cautionary vision of a society dominated by technological advancements and centralized authority, challenging the ideals of technocratic governance and raising ethical concerns about the loss of personal autonomy.[20] | United Kingdom |

| 1932 (late year) | Movement activity | Multiple groups across the United States begin identifying as technocrats, advocating for systemic reforms based on scientific and engineering principles. Their proposals often include energy-based economic structures, centralized planning, and the elimination of market-driven inefficiencies. The growing popularity of technocratic ideas during the Great Depression reflects widespread dissatisfaction with existing institutions.[50] | United States |

| 1932–1933 | Criticism | Spectacular examples of technological displacement cited by Scott, such as road-building machines and futuristic plants, are shown to be exaggerated or misrepresented. This led to criticism of technocracy as relying on advertising-style claims rather than scientific rigor.[39] | United States |

| 1933 (January) | Movement activity | The Committee on Technocracy disbands within a year due to criticisms of Howard Scott's academic qualifications, concerns over the group's data, and internal disagreements on social policy. In January, the organization splits into two factions: the "Continental Committee on Technocracy" and "Technocracy Incorporated."[2] | United States |

| 1933 (January) | Criticism | Howard Scott publishes an article in Harper's Magazine, bringing technocracy’s ideas to a wider audience. The article argues that technological advancements and increasing industrial efficiency will inevitably displace labor, rendering traditional economic systems obsolete. However, Scott’s claims are met with skepticism, sparking public debate over the movement’s bold predictions and its interpretation of technological trends. Critics question the feasibility of replacing market economies with a system based on scientific governance and energy accounting.[39] | United States |

| 1933 (January) | Movement activity | The American Technocracy movement fragments into opposing factions, with some factions prioritizing strict scientific governance, while others seeking broader social reforms. Howard Scott, the movement's original leader, retains control of Technocracy Inc., while rival groups pursue alternative interpretations. This fragmentation weakens the movement’s influence and hinders its long-term impact.[20] | United States |

| Early 1930s | Program | With the Great Depression exposing the failures of orthodox economic systems, Howard Scott and some members of the 1919 group reunite to conduct a statistical study on the effects of technological advancement on the economy. The research is funded by Columbia University and the American Institute of Architects.[39] | United States |

| 1933 | Publication | Harold Loeb publishes Life in a Technocracy: What It Might Be Like, a fictionalized utopian account that explores daily life in a society governed by engineers and scientists. Inspired by the ideas of Technocracy Incorporated, Loeb envisions a North America that has replaced its capitalist system with an energy-based economy. Citizens receive goods and services based on energy certificates rather than money, and work is distributed efficiently according to technical needs rather than market demand. The book seeks to make the abstract principles of technocracy tangible to the public, imagining how rational planning could eliminate poverty, inequality, and waste. Loeb’s work plays a significant role in popularizing the ideals of the American Technocracy movement during the Great Depression.[51][20] | United States |

| 1933 | Movement activity | The Continental Congress for Technocracy organizes a major conference in Chicago during the World’s Fair, providing a platform to discuss the movement’s vision for a scientifically managed economy. The event attracts engineers, economists, and technocrats who debate the potential of replacing market-driven capitalism with a system based on energy accounting and industrial efficiency. The conference helps popularize technocracy’s ideas, emphasizing the role of technology and expert governance in economic planning.[52] | United States |

| 1933 | Publication | H.G. Wells publishes The Shape of Things to Come, a speculative future history that explores the collapse of global political systems and the eventual emergence of a technocratic world state. Wells envisions a future where traditional governance gives way to a rational order led by experts—scientists, engineers, and planners—who restructure economics along the lines of physical science rather than market ideology. His vision aligns with the ambitions of American Technocracy, particularly its call for energy accounting and the replacement of the price system. While often utopian in tone, Wells also acknowledges the authoritarian risks of elite rule. The novel contributes to popularizing technocratic ideals during a time of economic crisis and rising faith in expertise.[53][54][20] | United Kingdom |

| 1933 | Program | The Technocrats publish a report highlighting a pivotal shift in the role of technology in society. They assert that "technology has now advanced to a point where it has substituted energy for man-hours on an equal basis," reflecting the transformative power of mechanization and automation. This marked a significant milestone in industrial progress, where machines powered by energy could perform tasks as efficiently as human labor. The statement emphasizes the movement's belief in the potential of technology to reshape economies, reduce manual labor, and optimize resource use, while also raising questions about employment, wealth distribution, and societal adaptation.[47] | United States |

| 1933 (March) | Movement activity | Howard Scott formally establishes Technocracy, Inc., solidifying the technocratic movement as an organized entity. This marks a shift toward a more structured and visible presence, with the organization adopting grey-toned regalia, which gives it a paramilitary and quasi-fascist appearance. The group’s meetings are often initiated and concluded with a hand salute similar to that used by the U.S. armed forces, reflecting the growing militaristic tone of its ideology. Technocracy, Inc. advocates for a system where engineers and technical experts govern economic and industrial processes, challenging traditional capitalist structures.[20] | United States |

| 1933 | Publication | Stuart Chase publishes a pamphlet on technocracy, extending Scott’s thesis on automation and labor. In the pamphlet, Chase suggests that automation displaces manual workers, shifting them to service trades, thus challenging Marxist class struggle theories. He predicts that continued automation will lead to the collapse of Marxian economic theories and industrial labor organization. Chase argues that technological development inherently disrupts the capitalist system, citing increased unemployment and pressure on the price system.[39] | United States |

| 1933 | Movement activity | The Technocracy Movement loses public interest as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs dominate public attention, addressing the immediate economic crisis. The movement fades into obscurity for nearly a decade.[39][32] | United States |

| 1933 | Movement activity | The Technocrats’ Magazine releases its final issue, marking a symbolic end to the most vibrant phase of the early Technocracy movement in the United States. The magazine had served as a key communication tool for the movement, promoting its core ideas such as energy accounting, scientific governance, and the replacement of the price system with a rational, expert-led economic model. Its visually striking final issue features cover art by famed pulp illustrator Norman Saunders, reflecting an effort to broaden appeal through engaging design. However, by this time, the movement faces growing public skepticism, internal fragmentation, and competition from more pragmatic New Deal policies. The magazine’s discontinuation reflects the waning public enthusiasm for technocracy during this turbulent period.[55] | United States |

| 1934 (September) | Publication | Technocracy Incorporated begins publishing the Technocracy Digest, a mimeographed bulletin aimed at educating members and the public on the organization's ideas. The Digest features articles on energy accounting, critiques of the price system, and discussions of scientific governance. It serves as an important communication tool for spreading technocratic doctrine in North America during a time of economic crisis and public interest in alternative governance models. The publication would continue sporadically into later decades, contributing to the survival of the movement well beyond its 1930s heyday.[56][57] | United States |

| 1934 | Publication | Technocracy inc. produces Science Versus Chaos by Howard Scott, which is the text of his concluding speech at the ill-fated Continental Convention on Technocracy. This pamphlet is distributed by Scott on his continent-wide tour, and would go through several printings.[58] | United States |

| 1934 | Publication | Technocracy: Some Questions Answered is published as a pamphlet aiming to clarify the principles and goals of the Technocracy movement for a broader audience. Featuring a foreword by M. King Hubbert, a prominent geophysicist and early supporter of technocratic theory, the document sought to dispel misconceptions about the movement’s intentions and organizational model. One of its most controversial positions is the explicit exclusion of artists and humanists from the movement’s proposed social and industrial framework. Technocracy Inc. argues that these roles are not essential to the scientific and technical management of society, reflecting a narrow utilitarian worldview focused on efficiency and engineering. The pamphlet underscores the movement’s emphasis on technical expertise while drawing criticism for its rigid view of cultural and social contributions.[20] | United States |

| 1934 | Publication | The Technocracy Study Guide is produced by Technocracy Inc. Initially a mimeograph form and later in a hardcover volume, it would be reprinted a number of times. Technocracy: Some Questions Answered, is another important piece of literature by the group.[58] | United States |

| 1935 | Publication | In his film Things to Come, H.G. Wells presents a vision of a “technological utopia,” governed by a “technological elite” who control a scientifically designed society. Wells advocates for world government, public ownership of capital, and centralized planning on a global scale, drawing comparisons to other sci-fi visions like Isaac Asimov's computer-controlled economy and E.E. Smith’s galactic government.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1936 | Movement activity | The Continental Committee on Technocracy formally disbands after years of internal conflict, divergent ideological views, and waning public interest. The committee had been formed in response to the growing Technocracy movement, aiming to provide an organized framework for implementing technocratic principles such as energy accounting and scientific governance. However, disagreements over leadership, strategy, and the role of political engagement fracture the group. Critics also question the scientific validity of its claims and the authoritarian tone of some proposals. Despite its dissolution, Technocracy Incorporated, led by Howard Scott, persisted independently, continuing to advocate for a society governed by engineers and scientists. The schism highlights enduring tensions between utopian ambition and organizational cohesion within the technocratic movement.[59][60] | United States |

| 1936 | Movement activity | Walter Fryers, a university student, travels back to Winnipeg after spending the summer trapping muskrats in the Saskatchewan River delta. He witnesses the devastating effects of the Great Depression and the dust bowl. Later in the year, Fryers attends the lecture and becomes an advocate for Technocracy.[55] | Canada |

| 1937 | Program | Technocracy, Inc. releases further details on its plan to replace money with energy certificates. Energy certificates would be issued, the total amount of which would "represent the total amount of net energy converted in the making of goods and provision of services."[47] | United States |

| 1939 | Movement activity | Amid growing tensions in Europe and heightened public anxiety over war and economic instability, Howard Scott makes a striking declaration during one of his public lectures. He claims that Technocracy is expanding so rapidly that “before long neither Canada nor the U.S. could discuss war without permission of this organization.” Scott's statement reflects the bold confidence of the movement during its peak years, envisioning a future in which governance would be handed over to trained experts rather than politicians. This comment also illustrates the technocratic belief that war and diplomacy, like energy and production, should be managed scientifically for the benefit of society rather than through partisan politics.[61][58] | United States, Canada |

| 1940 | Movement activity | Technocracy, Inc., led by Howard Scott, enters a period of significant decline. Once a highly visible movement advocating for a scientifically managed society based on energy accounting and technical expertise, the organization begins to lose momentum due to several factors. These include internal disagreements, public skepticism about its feasibility, the growing popularity of New Deal reforms, and the onset of World War II, which shifts attention away from utopian planning. The movement’s rigid structure and limited appeal outside its core following further contributes to its stagnation. Nonetheless, Technocracy, Inc. would continue to operate in a diminished form, maintaining a loyal but aging membership base and sporadically publishing materials, keeping the vision alive even as public relevance wane.[55][62] | United States |

| 1940 (June–July) | Movement activity | Due to opposition to World War II, the Technocracy movement is banned in Canada. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrest members of Technocracy Incorporated. The Canadian government also bans Technocracy alongside other organizations, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Communist Party. On July 16, Prime Minister Mackenzie King defends the ban in the House of Commons, alleging that Technocracy’s objective was to overthrow the government by force.[55] | Canada |

| 1940 (June 1) | Program | Delegates from Technocracy Inc. present Howard Scott’s controversial proposal for “total conscription” at the Western Conference of Municipalities in Yorkton, Saskatchewan. The plan calls for the complete mobilization of North America's population and resources—not only for military service but also for industrial production, infrastructure, and administrative coordination. Unlike conventional wartime conscription focused solely on soldiers, Scott's proposal extends to engineers, technicians, and workers, envisioning a scientifically managed war effort governed by technocratic principles. It reflects Technocracy Inc.’s belief that only through centralized planning and technical expertise can society respond effectively to global crises. The proposal aligns with the movement’s broader aim to replace political leadership with a functional, expertise-driven governance model.[55] | Canada |

| 1940 | Movement activity | A Winnipeg Free Press article reports on a unique technocratic wedding, highlighting the movement’s influence on social customs. Attendees, including the bride and groom, wear the signature grey suits associated with Technocracy Inc., symbolizing unity, efficiency, and a break from traditional societal norms.[55] | Canada |

| 1941 (April) | Criticism | During heightened wartime scrutiny in Canada, S.T. Wood, Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), publicly condemns Technocracy Inc. and other banned organizations, likening them to a “poison toadstool” that endangers the fabric of Canadian society. His remarks reflect official concerns that technocratic movements, with their paramilitary aesthetics, rejection of traditional political institutions, and radical visions for restructuring governance, pose a threat to national unity and security. At the time, the Canadian government groups Technocracy alongside organizations such as the Communist Party and Jehovah’s Witnesses, banning them under wartime emergency powers. Wood’s language illustrates how technocracy, despite its emphasis on scientific planning, is viewed with suspicion and framed as subversive in a time of national crisis.[55] | Canada |

| 1941 | Institutional development | Chinese intellectual and political reformer Luo Longji co-founds the China Democratic League (CDL), a political coalition advocating for democratic reform and technocratic governance in Republican China. Comprising scholars, professionals, and progressive politicians, the CDL seeks to balance the authoritarian tendencies of the Nationalist Party and the radicalism of the Communists by promoting governance rooted in expertise, rational planning, and the rule of law. Influenced by Western technocratic ideals—particularly those encountered by Chinese students studying abroad, such as in the United States—the CDL envisions a society led by educated elites capable of scientifically managing economic and social development. Luo's leadership would help frame technocracy as a middle path for modernization in a rapidly changing and politically polarized China.[43][63] | China |

| 1941 | Movement Activity | A significant rally of Technocracy Incorporated members takes place at the iconic Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. Attendees, clothe in the organization’s trademark grey suits symbolizing unity and scientific neutrality, gathered to hear a keynote speech by Howard Scott, the movement’s founder and principal spokesperson. The rally becomes emblematic of Technocracy’s growing visibility during a period of economic uncertainty and technological optimism in the United States. Scott emphasizes the inadequacies of the Price System and reiterates the organization’s core message: that society should be governed by scientifically trained engineers and technical experts rather than politicians or businessmen. The event showcases Technocracy’s ambition to build public momentum and legitimacy through spectacle and centralized leadership.[55] | United States |

| 1942 | Movement activity | Howard Scott reintroduces the movement as "Technocracy, Inc." It now operates as a well-funded organization with significant resources, including fleets of gray cars, uniforms, and salutes. Scott, now styled as a Leader, shifts the focus to broader social programs addressing war conduct, governance, international politics, and race relations. The movement gains traction, particularly in Los Angeles.[39] | United States |

| 1943 (October 15) | Governance | The Canadian government lifts the ban on technocratic organizations without providing an explanation. The ban is rescinded after these organizations pledge their support for the war effort, including a commitment to a program of total enrollment in the war.[55] | Canada |

| 1946-1947 | Movement activity | Technocracy Inc. conducts a series of speaking tours across the United States and Canada in an effort to revive interest in its vision of scientifically managed society. These events are part of a post-war push to reengage the public with technocratic ideas, particularly amid renewed concerns about economic planning, automation, and reconstruction. Technocracy representatives, often dressed in the movement’s signature grey uniforms, present lectures and demonstrations on topics such as energy accounting, the inefficiencies of the price system, and the potential for expert-led governance. The tours attract modest audiences, particularly in regions like British Columbia and California, where the movement had historically enjoyed support. Despite limited mainstream impact, these tours help sustain Technocracy Inc.’s presence into the postwar era.[55] | United States, Canada |

| 1947 (July 1) | Movement activity | "Operation Columbia" takes place as a caravan of 600 Technocracy-affiliated cars traveling from Los Angeles to British Columbia. The event coincides with a speech by Howard Scott, the leader of the Technocracy movement, in Vancouver. His address attracts 5,000 supporters, highlighting the movement’s continued influence in advocating for a scientifically managed economy. The large-scale demonstration reflects Technocracy’s organizational strength and its vision of replacing market-driven economies with data-driven governance based on technological expertise and resource management.[55] | United States, Canada |

| 1948 | Intellectual foundation | American mathematician Norbert Wiener publishes Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, formalizing the theory of feedback loops. His work inspires new models of governance based on system regulation, prediction, and information processing—key components of technocratic systems in later decades.[64] | United States |

| 1948 | Movement activity | The Technocracy movement in North America begins to wane, marked by internal disagreements and public disillusionment. A key factor in its decline is the failure of the predicted collapse of the Price System, which had been forecasted by leaders like Howard Scott as inevitable. As post-war economic recovery progress and capitalist systems remain intact, many supporters begin to question the movement’s core assumptions. Additionally, Technocracy Incorporates faced organizational stagnation, with diminishing recruitment and reduced public visibility. This period also sees increased skepticism toward sweeping utopian predictions, as attention shifts to Cold War politics and scientific professionalism within established institutions.[65][66] | United States |

| 1948 | Publication | American psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner, a leading proponent of behaviorism, publishes Walden Two, a utopian novel that explores how behavioral engineering can create an ideal society. The book presents a fictional community where human behavior is shaped through positive reinforcement rather than punishment, fostering cooperation, efficiency, and overall well-being. Rooted in Skinner’s theories, the society operates without traditional government or economic systems, relying instead on scientific principles to regulate work, education, and social interactions. Walden Two would spark discussions on the feasibility of behaviorally designed societies and influence later experiments in communal living and social engineering.[67] | United States |

| 1949 | Publication | English writer George Orwell publishes Nineteen Eighty-Four a dystopian novel depicting technocracy as a means for the Party to exercise total control over society. The regime utilizes technology for widespread surveillance, the dissemination of propaganda, and the manipulation of information and history. These technological tools are employed to suppress independent thought, eliminate dissent, and reinforce the Party's authority. Through this portrayal, Orwell critiques the potential for technology to be harnessed for authoritarian purposes, emphasizing the dangers of state control over both knowledge and personal freedom.[68] | United Kingdom |

| 1959 | Governance | Singapore implements state-led industrial planning, embodying technocratic principles by prioritizing rational governance, economic expertise, and scientific management. Lee Kuan Yew, its first prime minister, leads a government that embraces technocratic ideals, relying on experts, engineers, and economists to drive rapid industrialization. His administration adopts centralized planning, infrastructure development, and strategic investments in education and technology, transforming Singapore from a struggling colony into what would become a global economic hub. By promoting efficiency, meritocracy, and evidence-based policymaking, Singapore would become a model of technocratic governance. The nation's economic success illustrates how technocratic leadership can drive national development through rational, systematic planning.[69] | Singapore |

| 1960 | Governance | China, under Mao Zedong, is deep into the Great Leap Forward, a radical attempt at rapid industrialization through central economic planning. The policy collectivizes agriculture into large communes and pushes mass steel production in backyard furnaces. However, unrealistic targets and poor implementation leads to economic collapse and widespread famine. While the Great Leap Forward is centrally planned, it lacks the scientific and data-driven approach characteristic of technocracy. Instead of leveraging technological expertise for sustainable growth, it relies on ideological directives, demonstrating the risks of centralized planning without empirical evaluation and adaptive governance.[70] | China |

| 1967 | Governance | The term "technocracy" is applied to European Union (EU) integration, particularly in relation to the High Authority—later known as the European Commission—being guided by a Consultative Committee composed of representatives from various organizations. This reflects a shift toward "functional representation," where technical experts received input from industry and social groups, blending expert-driven governance with stakeholder consultation.[71] | Europe |

| 1968 | Governance | French President Charles de Gaulle resigns after rejecting a constitutional referendum, marking a public turn against centralized state-led expertise. The event is linked to the broader upheaval of May 1968, where student and worker movements protested the paternalism of technocratic governance and bureaucratic control.[72] | France |

| 1970 | Movement activity | Howard Scott, the founder and primary theorist of Technocracy Inc., passes away in Florida, marking the end of an era for the technocratic movement. Scott had been a central and often polarizing figure, shaping the organization's ideology around the principles of energy accounting, scientific management, and the rejection of price-based economics. His charismatic leadership and uncompromising vision had sustained the movement through its peak in the 1930s and its prolonged decline in the postwar years. Following Scott’s death, John T. Spitler is appointed as the new Continental Director of Technocracy Inc., inheriting an organization with a reduced but still active membership. Spitler’s leadership would continue the legacy of technocracy, though without the influence and visibility once commanded by its founder.[55][47] | United States |

| 1972 | Intellectual foundation | The Club of Rome publishes The Limits to Growth, which presents a groundbreaking study on the risks of unchecked economic and population growth. Conducted by an MIT research team, it uses computer modeling to analyze key factors like population, agriculture, resource depletion, industry, and pollution. The findings warn that, even with technological advances, Earth’s ecological limits can be exceeded before 2100. However, the book also emphasizes that forward-thinking policies can prevent collapse. Its reliance on data-driven analysis reflects a technocratic approach, advocating for scientific expertise and computational models to guide sustainable decision-making and global resource management.[73] | Global |

| 1972 | Governance | During Ferdinand Marcos's martial law period in the Philippines, the concept of technocracy gains prominence as the regime increasingly rely on technocrats to shape economic policy. Marcos appoints a group of experts, often from academic or business backgrounds, to key government positions, with the aim of fostering rapid economic development and modernization. These technocrats, who emphasize evidence-based decision-making, play a central role in the formulation of policies, including infrastructure projects, industrialization efforts, and agricultural reforms. While their strategies lead to some economic growth, they are also criticized for their close ties to the Marcos regime and alleged corruption.[74][75] | Philippines |

| 1973 | Intellectual foundation | Daniel Bell argues that experts are an indispensable part of the administrative staff in a political system, a view supported by Agarwal et al. (1993). This highlights the crucial role of technocrats in managing and implementing policies within a complex and modern society, emphasizing their essential contribution to the functioning of a technocracy.[76][77] | United States |

| Early 1970s | Movement activity | A series of events in the early 1970s, including the Vietnam War, Watergate scandal, and oil shocks, contribute to the discrediting of the technocratic vision. The failures of leadership, corruption, and inability to address both domestic and international challenges lead to widespread distrust in the elites’ competence and ethics.[1] | United States |

| 1975 | Program | The Brandt Report is commissioned by the World Bank and UN, calling for global coordination by experts to address poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation. It proposes energy and resource planning beyond national boundaries, relying on data-driven policies.[78] | Global |

| 1977 | Publication | American political scientist Robert D. Putnam publishes a study differentiating between two distinct categories of technocrats: those with expertise in engineering and those with expertise in economics. His analysis highlights that these groups diverge in specific characteristics, particularly in their perspectives on politics, equality, and social justice. Economic technocrats are more inclined than their engineering counterparts to acknowledge the significance of political dynamics, prioritize equality, and engage with issues related to social justice. This distinction suggests that technical specialization influences technocrats' broader ideological orientations and policy priorities.[43] | United States |

| 1980s–present | Governance | Following the death of Mao Zedong, China undergoes a significant shift toward technocratic leadership under Deng Xiaoping and subsequent leaders. The government increasingly promotes scientifically trained cadres, especially engineers and economists, to key positions in the party-state apparatus. By the 1990s and early 2000s, a majority of China’s top leaders—including Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Wen Jiabao—hold engineering backgrounds. This trend reflects a strategic embrace of evidence-based, growth-focused governance, prioritizing economic development, infrastructure, and technical expertise over ideological doctrine.[79] | China |

| 1985 | Criticism | American political scientist Robert Dahl argues that the "technocratic solution," which emphasizes specialized competence over political competence, represents a distortion of the democratic ideal of power redistribution. He suggests that this approach, by concentrating authority in the hands of experts rather than elected representatives, undermines the principle of political equality and participation, central to democratic systems. Dahl's critique highlights the potential dangers of relying too heavily on technocrats, as it can erode the democratic process and reduce citizens' influence in decision-making.[80] | United States |

| 1985 | Intellectual foundation | R. Alford and R. Friedland argue that the transition from industrial to post-industrial society has led to increased organizational complexity, necessitating both corporate and state planning by technocrats. This shift implies that politicians must rely on technocrats' expertise to achieve societal goals, highlighting the importance of technocratic input in navigating the complexities of modern governance.[81][76] | United States, Europe |

| 1987 | Intellectual foundation | O. M. Mugyenyi argues that politicians often adopt a populist stance, even on technical matters, while technocrats focus on expertise-driven decisions. He supports the use of technical experts, even if unpopular, as citizens trust elected leaders to formulate and implement development policies. Democracy allows political leaders to experiment with policies, even without a strong basis, as their success or failure is ultimately judged by voters at the end of their term. This dynamic between politicians and technocrats remains a key issue in governance and policy implementation.[82] | |

| 1987 | Governance | The collapse of the New Order (Indonesia) regime under Suharto begins a process of democratic and technocratic restructuring. Suharto had governed with the support of Western-trained economists—known as the "Berkeley Mafia"—whose policies emphasized macroeconomic stability and long-term planning, despite authoritarian rule. This marks one of Asia's clearest examples of technocrats operating under undemocratic conditions.[83] | Indonesia |

| 1991 | Governance | After the fall of the Soviet Union, post-communist states such as Poland and the Czech Republic employ Western-educated technocrats to design privatization schemes and fiscal reform. These transitions are marked by temporary technocratic cabinets, often praised by international institutions for their rational, market-oriented focus.[84] | Eastern Europe |

| 1995 (October 31) | Movement activity | Robert Cromie, then publisher of the Vancouver Sun, writes a letter to Howard Scott, the founder of Technocracy Inc., expressing his support for the technocratic vision. Cromie’s endorsement comes decades after the peak of the Technocracy movement, signifying its enduring influence in certain circles of Canadian intellectual and media elites. The letter reflects ongoing interest in technocratic principles such as rational governance, scientific planning, and energy-based economics—particularly within regions like British Columbia, where Technocracy Inc. had historically found receptive audiences. Although largely marginalized by the late 20th century, Scott’s ideas would continue to attract attention from those disillusioned with traditional politics and inspired by the promise of a society guided by expertise and systemic efficiency.[55] | Canada |

| 1999–present | Governance | The European Central Bank and other EU institutions increasingly rely on technocrats to manage economic policy and regulation, particularly during the Eurozone crisis (2009–2014). Institutions like the European Commission are staffed by policy experts and economists who make decisions with limited direct input from voters. The growing role of non-elected experts has led to public criticism of a “Brussels technocracy,” as decisions about monetary policy, austerity, and regulation are perceived to bypass democratic accountability.[85] | Europe |

| 2000 | Movement influence | The term "technocracy" gains some traction, particularly in discussions about the rise of technocratic leadership and policy-making, often seen as a shift towards expertise-driven governance over traditional political processes.[86][87][88] | |

| 2003–present | Governance | The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) increasingly adopts a technocratic model of regional integration. While avoiding political union, ASEAN focuses on technical coordination in areas such as infrastructure, energy, public health, and trade facilitation. Technocrats and policy experts drive this integration, producing frameworks such as the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint. This quiet technocrat-led regionalism contrasts with the more politicized EU model.[89] | Southeast Asia |

| 2007 | Criticism | Andrew Wallace defines technocracy as "rule by skill," comparing it to a Platonic meritocracy of the skilled. This view suggests that technocrats may be seen as anti-democratic, although their influence within a democracy can be positive. Technocrats' expertise is not limited to hard sciences but extends to other fields, and their role in a democracy is justified by the need for specialized knowledge. Democracies may require experts to address complex issues that the general public may not fully comprehend, highlighting the potential value of technocratic governance in democratic systems.[90][76] | |

| 2010s–present | Governance | Advances in AI, big data, and machine learning give rise to “algorithmic technocracy,” where automated decision systems influence public policy, legal sentencing, hiring, and resource distribution. Cities adopt data dashboards and predictive algorithms to manage policing and public health. Critics warn that these systems may reinforce biases and lack democratic oversight, raising ethical questions about accountability in data-driven governance.[91][92] | Global |

| 2015 | Criticism | In his book The Lure of Technocracy, Jürgen Habermas critiques the European Union's political legitimacy and presentes a vision of politics opposed to technocracy. Habermas's critique highlights a tension between deliberative democracy and technocratic governance, forecasting a potential collapse of the EU if it didn’t adapt.[93] | Europe |

| 2018 | Governance | The city of Barcelona implements a pioneering "data commons" model to regulate digital platforms and protect citizens' rights. Using open-source systems and civic data audits, the city explores a new, decentralized technocratic model rooted in transparency and algorithmic accountability.[94][95] | Spain |

| 2020 | Governance | The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 spotlights a resurgence of technocratic governance, as political leaders in many countries increasingly defer to scientific and technical experts for policymaking guidance. Public health officials, epidemiologists, and data scientists play central roles in shaping lockdown strategies, public communication, and resource allocation. Governments in countries such as Germany, South Korea, and New Zealand gain international attention for integrating expert advice into decision-making structures, often elevating scientists to daily briefings and central command roles. While this reliance on expertise helps improve public trust in some cases, it also raises questions about the democratic legitimacy of technocratic power and the limits of scientific consensus in shaping value-laden policy decisions.[96] | Global |

| 2020s | Governance | Scholars and human rights organizations highlight the rise of digital authoritarianism, particularly in China, where AI and surveillance technologies are deployed to monitor behavior, assign social credit scores, and suppress dissent. These tools create a new form of technocratic control through ubiquitous data collection and centralized algorithmic decision-making. The model influences other authoritarian regimes, who adopt surveillance-driven governance mechanisms that emphasize control over democratic participation.[97] | Global |

| 2021 | Governance | The appointment of Mario Draghi—former European Central Bank president—as Prime Minister of Italy marks a resurgence of technocracy in the EU. Known as "Super Mario," Draghi is seen as a non-partisan expert brought in to stabilize Italy’s economy and implement pandemic recovery plans using EU funds. His tenure underscores the role of unelected experts in national crisis management.[98] | Italy |

| 2023 | Governance | The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into governance structures accelerates globally, marking a significant shift toward algorithmic and data-driven decision-making in both public and private sectors. Governments increasingly adopt AI tools for policy modeling, resource allocation, risk assessment, and service delivery—particularly in areas such as healthcare, urban planning, and taxation. The rise of large-scale AI systems enables real-time data analysis and predictive analytics, offering the promise of more efficient, responsive, and evidence-based governance. However, this trend also raises ethical and democratic concerns, including issues of transparency, accountability, bias, and the erosion of human oversight in critical decisions. The growing influence of AI in public policy reflects a technocratic evolution, where expertise is augmented—and in some cases displaced—by computational systems.[99][100] | Global |

| 2024 | Program | The World Economic Forum announces a framework for “AI Governance Principles” to guide the ethical deployment of generative AI in government, education, and urban planning. The document advocates for global technocratic standards in algorithmic transparency, safety, and equity.[101] | Global |

Numerical and visual data

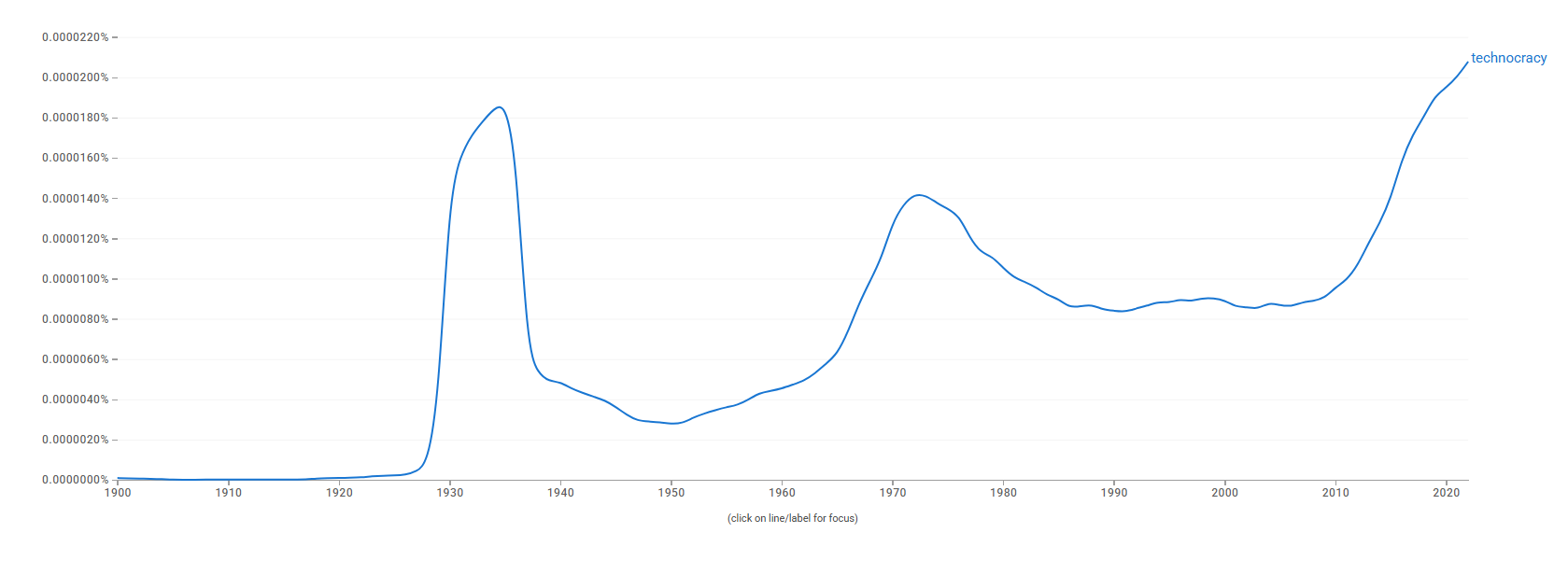

Google N-gram viewer

The chart below shows how often the word "technocracy" appears in books over time. See the big spike in the 1930s, when the movement emerges. The word's use then stabilizes until the late 20th and early 21st centuries, when it starts increasing again. This recent rise could be linked to concerns about technology's impact on society and the environment.[102]

Google trends

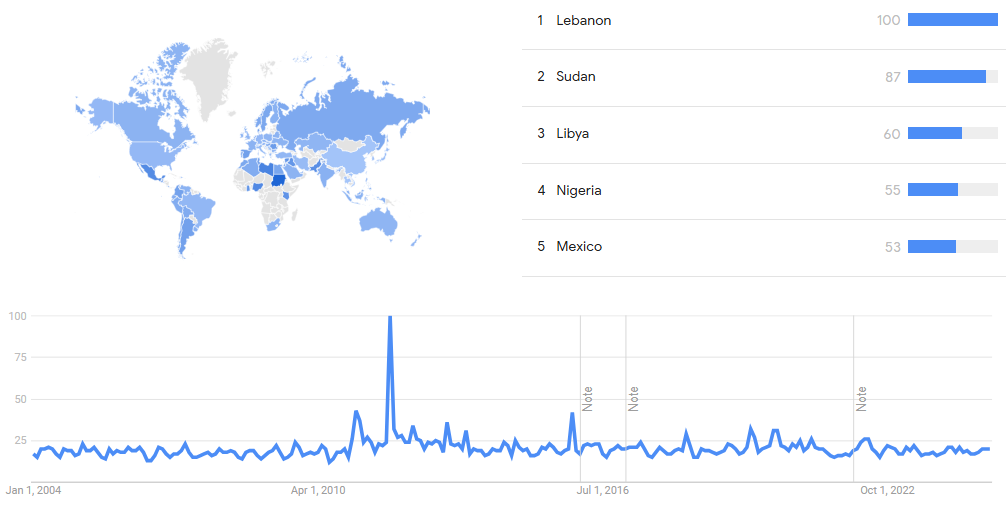

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Technocracy (Political ideology), from January 2004 to January 2025, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[103]

Wikipedia views

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Technocracy Hypothesis". Roots of Progress. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Technocracy". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The Technate: A Future North American Superpower?". youtube. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Technocratic Society: Evolution from Philosophical Ideals to Today's Governance". Medium. Tecnosphia. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ↑ Canfora, Luciano (1990). The Vanished Library. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520072558.

- ↑ Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Darby, H.C. (1977). Domesday England. CUP Archive.

- ↑ Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Reaktion Books.

- ↑ Template:Cite thesis

- ↑ Hughes, Lindsey (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the Great. Yale University Press.

- ↑ A.G. Cross (1993). "Peter the Great's Academicians: Foreign Scientists in the Service of Russia". Oxford Slavonic Papers. 26: 27–53.

- ↑ Gary Marker (1985). Publishing, Printing, and the Origins of Intellectual Life in Russia, 1700–1800. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ {{cite book |author=Michael T. Florinsky |title=Russia: A History and an Interpretation |publisher=Macmillan |year=1953}

- ↑ Laplace, Pierre-Simon (1951). A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Dover.

- ↑ "Saint-Simon's Technocratic Internationalism (1802–1825)". Oxford Intellectual History. University of Oxford. 2025. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ↑ French Wikipedia

- ↑ Phillips, John A. (1992). The Great Reform Bill in the Boroughs. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jansen, Marius (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Oh, Kyunghwan (2024-04-15). "A non-conforming technocratic dream: Howard Scott's technocracy movement". Technology in Society: 108–123. doi:10.1080/17449359.2024.2343657. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 Waddell, Nathan. "Aldous Huxley, High Art, and American Technocracy". Nottingham Repository. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen. "The Theory of Business Enterprise". Domínio Público. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen (2010). The Theory of Business Enterprise. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1163207578. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen (1904). The Theory of Business Enterprise. Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "The Futurist Manifesto (1909)". Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ↑ Giannantonio, Cristina; Hurley, Amy E. (2011). "Frederick Winslow Taylor: Reflections on the Relevance of The Principles of Scientific Management 100 Years Later". Journal of Business and Management. 17 (1). doi:10.1504/JBM.2011.141187.

- ↑ Zuffo, Riccardo Giorgio. "Taylor is Dead, Hurray Taylor! The "Human Factor" in Scientific Management: Between Ethics, Scientific Psychology and Common Sense" (PDF). Journal of Business and Management. University “G. d’Annunzio” of Chieti. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ↑ Drury, Horace B. (1915). Scientific Management: A History and Criticism. Columbia University. Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ↑ "Article Summary". Project MUSE. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ↑ Duskin, J.E. (2001). "6". In Stalinist Reconstruction and the Confirmation of a New Elite, 1945–1953 (ed.). The Implications of Stalin’s Technocracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781403919458_6. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link) - ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Technocracy". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Technocracy Movement | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ↑ "Thorstein Veblen". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Thorstein Veblen Definition & Meaning". Investopedia. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Peter J. Taylor. Technocratic Optimism, H.T. Odum, and the Partial Transformation of Ecological Metaphor after World War II Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 21, No. 2, June 1988, p. 213.

- ↑ "Questioning of M. King Hubbert, Division of Supply and Resources, before the Board of Economic Warfare" (PDF). 1943-04-14. Retrieved 2008-05-04.p8-9 (p18-9 of PDF)

- ↑ William E. Akin (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocracy Movement 1900-1941, University of California Press, p. 37.

- ↑ William E. Akin (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocracy Movement 1900-1941, University of California Press, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 Hal Draper (March 1944). "Technocracy and Socialism". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen. The Engineers and the Price System. Routledge. ISBN 9780878559152. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Thorstein Veblen. The Engineers and the Price System. Routledge. ISBN 113853546X. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "The Engineers and the Price System". Routledge & CRC Press. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 "Perspective: The Benefits of Technocracy in China". Issues in Science and Technology. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ↑ Kaes, Anton (1989). "Machines, Metropolis, and the Technocratic Dream". Film Quarterly. 43 (1).

- ↑ Alexander Bogdanov (1965). "Tectology: The Universal Science". Slavic Review. 24 (1). Translated by George Gorelik: 1–16. doi:10.2307/2492874.

- ↑ Loren Graham (1993). The Ghost of the Executed Engineer: Technology and the Fall of the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Berndt, Ernst R. "From technocracy to net energy analysis" (PDF). dspace.mit.edu. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ↑ Marion King Hubbert (1945). Technocracy Study Course (PDF). Technocracy Inc. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Marion King Hubbert (1945). "Technocracy Study Course". Internet Archive. Technocracy Inc. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ↑ Beverly H. Burris (1993). Technocracy at work State University of New York Press, p. 30.

- ↑ Loeb, Harold (1933). Life in a Technocracy: What It Might Be Like. Viking Press.

- ↑ Henry Elsner, Jr. (1967). The Technocrats: Prophets of Automation. Syracuse University.

- ↑ Wells, H.G. (1933). The Shape of Things to Come. Macmillan.

- ↑ Waddell, Craig (2003). "Technocracy and the Rhetoric of the Technological Fix". Poroi. 2 (1): 94–110.

- ↑ 55.00 55.01 55.02 55.03 55.04 55.05 55.06 55.07 55.08 55.09 55.10 55.11 55.12 "The Last Utopians". Canada's History. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ↑ Akin, William E. (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocrat Movement, 1900–1941. University of California Press. p. 174.

- ↑ Segal, Howard P. (1995). "Technocracy and American Culture". Technology and Culture. 36 (2): 360–366.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 "The technocrats 1919-1967 - Summit Research Repository" (PDF). summit.sfu.ca. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ↑ Howard P. Segal (October 1, 1977). "Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocrat Movement, 1900-1941 (Book Review)". Technology and Culture. 18 (4): 714. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ↑ Fischer, Frank (1990). Technocracy and the Politics of Expertise. Sage Publications. p. 86.

- ↑ Akin, William E. (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocrat Movement, 1900–1941. University of California Press. p. 191.

- ↑ Akin, William E. (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocracy Movement, 1900–1941. University of California Press. p. 203.

- ↑ "Concept 1618478". EPFL GraphSearch. Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ↑ Wiener, Norbert (1948). Cybernetics. MIT Press.

- ↑ Akin, William E. (1977). Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocrat Movement, 1900–1941. University of California Press. pp. 212–214.Segal, Howard P. (1995). "Technocracy and American Culture". Technology and Culture. 36 (2): 360–366.

- ↑ Adair, David (1967). The Technocrats 1919-1967: A Case Study of Conflict and Change in a Social Movement. p. 111.