Difference between revisions of "Timeline of biohacking"

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

! Year !! Month and date !! Event type !! Approach (when applicable) !! Details | ! Year !! Month and date !! Event type !! Approach (when applicable) !! Details | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1930s || || || || The Mertonian ethos is proposed by American sociologist {{w|Robert K. Merton}} as an account of scientist's norms of behavior.<ref name="Delfanti">{{cite book |last1=Delfanti |first1=Alessandro |title=Biohackers: The Politics of Open Science |date=7 May 2013 |publisher=Pluto Press |isbn=978-0-7453-3280-2 |url=https://books.google.com.ar/books/about/Biohackers.html?id=aEFTLwEACAAJ&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y |language=en}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1960 || || || || "{{w|Manfred Clynes}} and Nathan Klines’ 1960 article, "Cyborgs and Space"" | | 1960 || || || || "{{w|Manfred Clynes}} and Nathan Klines’ 1960 article, "Cyborgs and Space"" | ||

Revision as of 15:41, 19 July 2021

This is a timeline of biohacking.

Contents

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 2000s | Increased proliferation | "the dissemination of genetic engineering techniques has continued, even accelerated, thanks in part to an economic downturn in the 2000s that prompted several struggling biotech firms to sell off their equipment to biohacker collectives"[1] |

Visual and numerical data

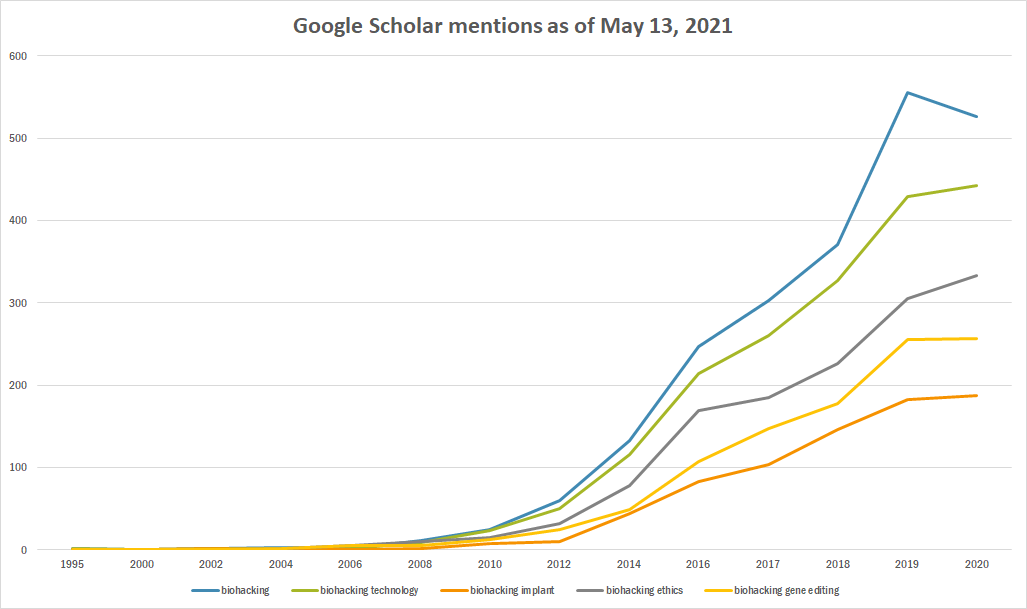

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 13, 2021.

| Year | biohacking | biohacking technology | biohacking implant | biohacking ethics | biohacking gene editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2004 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 2006 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2008 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| 2010 | 25 | 23 | 7 | 15 | 13 |

| 2012 | 60 | 50 | 10 | 32 | 24 |

| 2014 | 133 | 116 | 44 | 78 | 49 |

| 2016 | 247 | 214 | 83 | 169 | 107 |

| 2017 | 303 | 260 | 104 | 185 | 147 |

| 2018 | 371 | 327 | 146 | 226 | 178 |

| 2019 | 556 | 429 | 182 | 305 | 255 |

| 2020 | 527 | 442 | 187 | 333 | 257 |

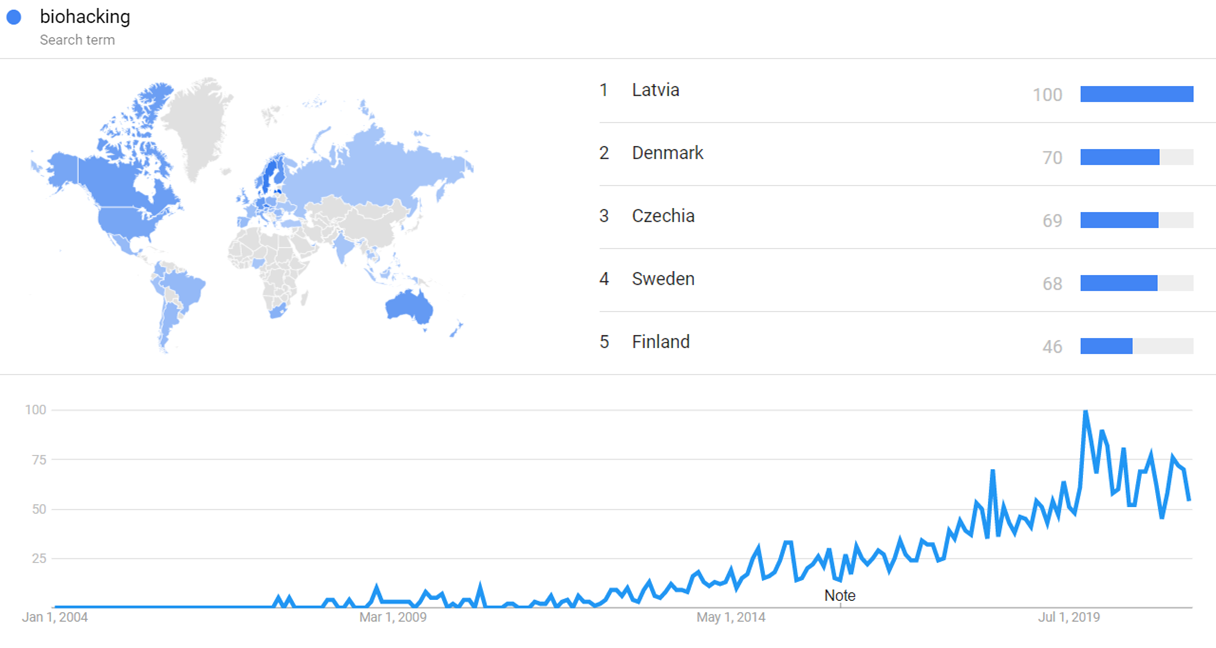

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Biohacking (search term), from January 2004 to Month 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[2]

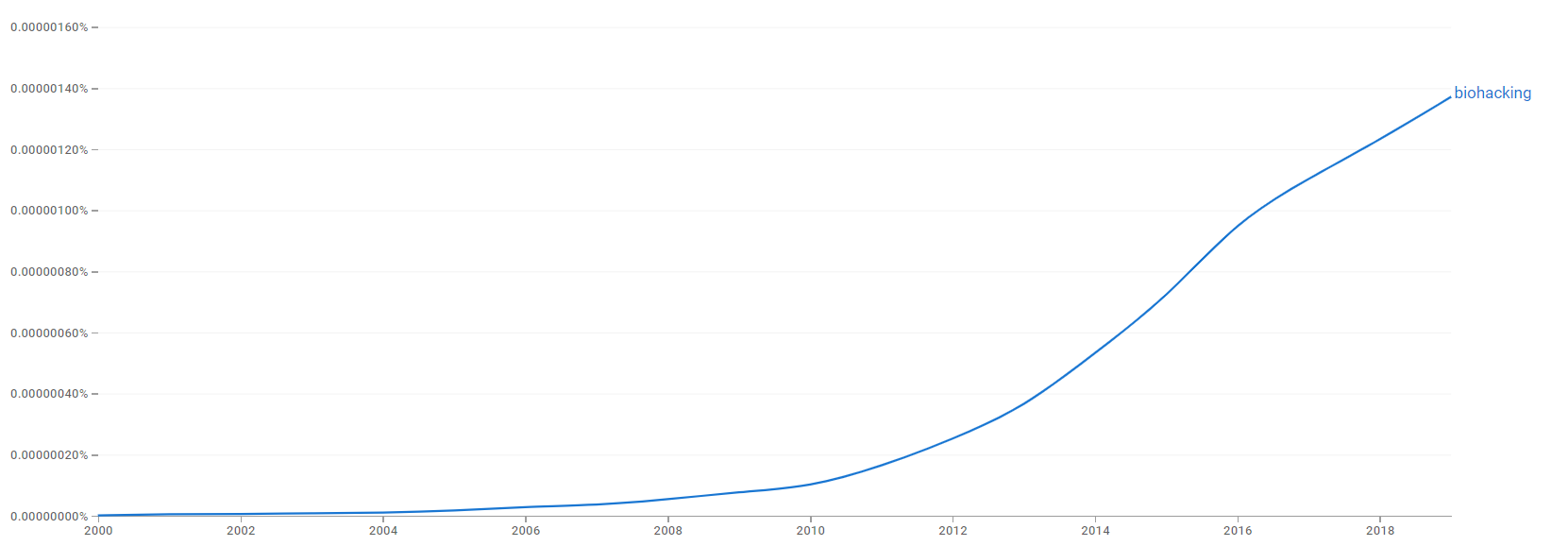

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Biohacking, from 2000 to 2019.[3]

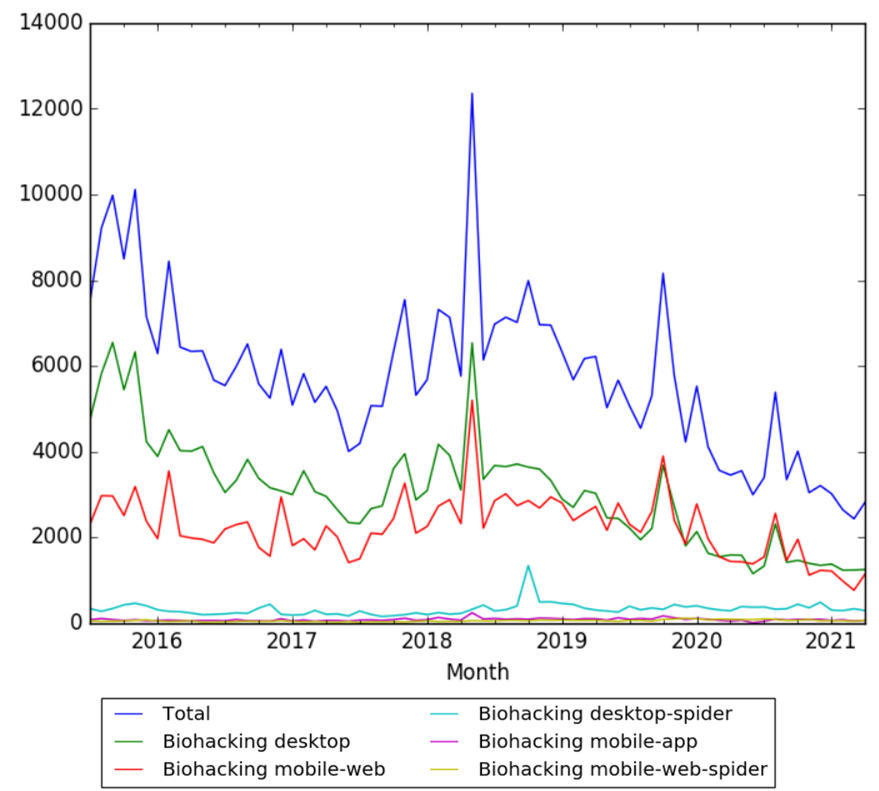

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Biohacking, from July 2015 to April 2021. [4]

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Event type | Approach (when applicable) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930s | The Mertonian ethos is proposed by American sociologist Robert K. Merton as an account of scientist's norms of behavior.[5] | |||

| 1960 | "Manfred Clynes and Nathan Klines’ 1960 article, "Cyborgs and Space"" | |||

| 1984 | "1984 - The 1984 Novel Neuromancer by William Gibson is often attributed as the cause in the rise of transhumanism culture popularity in modern times, and for coining terminology and ideas that form the basis of modern Cyberpunk and body hacking culture."[6] | |||

| 1985 | Donna Haraway’s publishes her Cyborg Manifesto, giving rise to the cyborg theory.[7] | |||

| 1986 | Hacker Manifesto | |||

| 1988 | "“You can pick up any recent issue of Science magazine, flip through it and find ads for kit after kit of biotechnology techniques,” says molecular biologist Tom St. John of the Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.21 Remarkably, St. John made this comment in 1988 in a Washington Post article, one titled Playing God in Your Basement and likening biohacking to 1970s computer hacking."[1] | |||

| 2005 | "Amal Graafstra is known for implanting an RFID chip in 2005 and developing human-friendly chips including the first ever implantable NFC chip."[8] | |||

| 2009 | "Then in 2009, the National Security Council dramatically changed perspectives. It published the National Strategy for Countering Biological Threats, which embraced “innovation and open access to the insights and materials needed to advance individual initiatives,” including in “private laboratories in basements and garages.”"[9] | |||

| 2013 | Biotech startup company Dangerous Things is founded by Amal Graafstra.[10] | |||

| 2014 | October 17 | Literature | Ari R. Meisel publishes Intro to Biohacking.[11] | |

| 2015 | May | Literature | James Lee publishes The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks.[12] | |

| 2015 | Literature | James Lee publishes The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks.[13] | ||

| 2016 | " In 2016, sick of suffering from severe stomach pain, Zayner decided to give himself a fecal transplant in a hotel room. He had procured a friend’s poop and planned to inoculate himself using the microbes in it. Ever the public stuntman, he invited a journalist to document the procedure. Afterward, he claimed the experiment left him feeling better."[9] | |||

| 2020 | August 20 | German techno-thriller television series Biohackers is released on Netflix.[14] |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]

- [4]

- Biorobotics

- Biopunk

- Body hacking

- Neurohacking

- Neuroenhancement

- Category:Do it yourself

- Do-it-yourself biology

- Dave Asprey

- Books

- Body hacking

- Neurohacking

- [5]

- Cyborg

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vargo, Marc E. (11 August 2017). The Weaponizing of Biology: Bioterrorism, Biocrime and Biohacking. McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4766-2933-9.

- ↑ "Biohacking". Google Trends. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking". books.google.com. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ Delfanti, Alessandro (7 May 2013). Biohackers: The Politics of Open Science. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-3280-2.

- ↑ "Neuromancer | Summary & Cultural Impact". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ↑ "Close Reading of Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway | Darat al Funun". daratalfunun.org. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ "The xNT implantable NFC chip". Indiegogo. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Samuel, Sigal (25 June 2019). "How biohackers are trying to upgrade their brains, their bodies — and human nature". Vox. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ "Dangerous Things". Dangerous Things. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ Meisel, Ari R. Intro to Biohacking. Createspace Independent Pub. ISBN 978-1-5025-1546-9.

- ↑ Lee, James. The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5121-2127-8.

- ↑ Lee, James. The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5121-2127-8.

- ↑ [biohackers "We are the Biohackers"] Check

|url=value (help). Biohackers. Pluto Press. pp. 111–129. Retrieved 17 April 2021.