Difference between revisions of "Timeline of biohacking"

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2013 || Notable case || {{w|Bioluminescence}} || A team of three biohackers affiliated with Biocurious as well as with Genome Compiler conduct a crowd-sourcing campaign to raise money for developing bioluminescent plants that would glow in the dark. The idea is presented as a step towards a more sustainable future when streets would no longer be lit by electric lamps but by glowing trees. Once the project reaches its goals, each subscriber would receive envelopes with seeds of the genetically modified plants. By June 2013, 6000 hackers would be subscribed, bringing in almost 500.000 dollars to fund the project.<ref name="Keulartz"/> | | 2013 || Notable case || {{w|Bioluminescence}} || A team of three biohackers affiliated with Biocurious as well as with Genome Compiler conduct a crowd-sourcing campaign to raise money for developing bioluminescent plants that would glow in the dark. The idea is presented as a step towards a more sustainable future when streets would no longer be lit by electric lamps but by glowing trees. Once the project reaches its goals, each subscriber would receive envelopes with seeds of the genetically modified plants. By June 2013, 6000 hackers would be subscribed, bringing in almost 500.000 dollars to fund the project.<ref name="Keulartz"/> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2013 || Notable case || Device implant || "In 2013, biohacker Tim Cannon had this biosensor implanted into his arm, between the skin and the muscle. The Circadia checks your temperature and your pulse, then syncs this information to an Android device. It also conveys information by lighting up."<ref name="You've gotta">{{cite web |title=You've gotta see these human cyborgs (WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGES) |url=https://www.cnet.com/pictures/youve-got-to-see-these-human-cyborgs/ |website=CNET |access-date=9 September 2021 |language=en}}</ref> || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2013 || Organization || || Biotech startup company {{w|Dangerous Things}} is founded by Amal Graafstra.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.dangerousthings.com|title=Dangerous Things|website=Dangerous Things|language=en-us|access-date=5 April 2021}}</ref> It is a {{w|Seattle}} based [[w:Cybernetics|cybernetic]] [[w:Microchip implant (human)|microchip]] [[w:Body hacking|biohacking]] implant retailer company.<ref>{{cite web |title=Implantable RFID company Dangerous Things looks outside the body with hacker-friendly Bluetooth switch |url=https://www.geekwire.com/2015/implantable-rfid-company-dangerous-things-looks-outside-the-body-with-hacker-friendly-bluetooth-switch/ |website=GeekWire |access-date=6 September 2021 |date=3 June 2015}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | | 2013 || Organization || || Biotech startup company {{w|Dangerous Things}} is founded by Amal Graafstra.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.dangerousthings.com|title=Dangerous Things|website=Dangerous Things|language=en-us|access-date=5 April 2021}}</ref> It is a {{w|Seattle}} based [[w:Cybernetics|cybernetic]] [[w:Microchip implant (human)|microchip]] [[w:Body hacking|biohacking]] implant retailer company.<ref>{{cite web |title=Implantable RFID company Dangerous Things looks outside the body with hacker-friendly Bluetooth switch |url=https://www.geekwire.com/2015/implantable-rfid-company-dangerous-things-looks-outside-the-body-with-hacker-friendly-bluetooth-switch/ |website=GeekWire |access-date=6 September 2021 |date=3 June 2015}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | ||

Revision as of 14:12, 9 September 2021

This is a timeline of biohacking, attempting to describe events related to the do-it-yourself biology movement, as well as body hacking, and self-experimentation in medicine in general.

Contents

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- Concept development

- Ideology development

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s–1960s | Early movements | The Do-it-Yourself movement gains momentum in the United States during this time, after decades of seeding by publications such as Popular Science (first published in 1872) and Popular Mechanics (1902).[1] he hacker ethic emerges within the first hacker communities in the United States.[2] |

| 1970s–1980s | Computer hacking birth | The popularization of computers since the late 1970s gives rise to computer hacking,[3] a predecesor sharing a number of parallels with the future “biohacking” ecosystem.[4] In the early 1980s, Richard Stallman founds the Free Software Foundation.[5] The modern neurohacking movement begins.[6] |

| 1990s | The do-it-yourself movement becomes popular in this decade.[7] An explotion of free operating system and desktop environment projects lay the groundwork of a free and open-source software ecosystem in this decade.[8] | |

| 2000s | Increased proliferation | After a brief period marked by a lack of research in the area, neurohacking starts regaining interest in the early decade.[9][10] An economic downturn prompts several struggling biotech firms to sell off their equipment to biohacker collectives, accelerating the dissemination of genetic engineering techniques.[11] |

| 2010s | Biohacker spaces consolidation | The first biohacker spaces open in the United States.[12] In this decade, a new generation of biologists embraces the do-it-yourself ethic of computer programming.[13] |

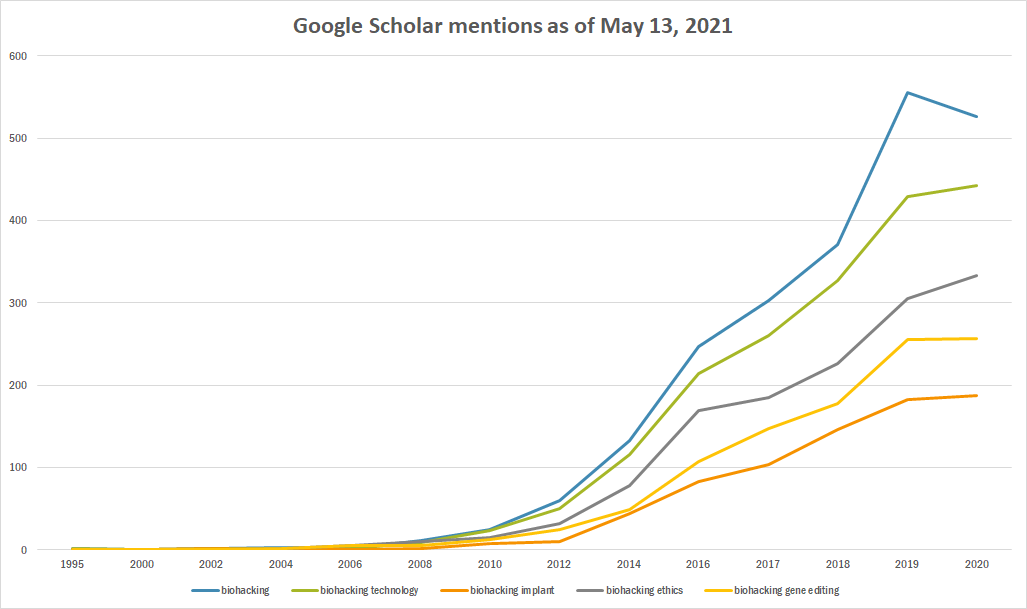

Visual and numerical data

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 13, 2021.

| Year | biohacking | biohacking technology | biohacking implant | biohacking ethics | biohacking gene editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2004 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 2006 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2008 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| 2010 | 25 | 23 | 7 | 15 | 13 |

| 2012 | 60 | 50 | 10 | 32 | 24 |

| 2014 | 133 | 116 | 44 | 78 | 49 |

| 2016 | 247 | 214 | 83 | 169 | 107 |

| 2017 | 303 | 260 | 104 | 185 | 147 |

| 2018 | 371 | 327 | 146 | 226 | 178 |

| 2019 | 556 | 429 | 182 | 305 | 255 |

| 2020 | 527 | 442 | 187 | 333 | 257 |

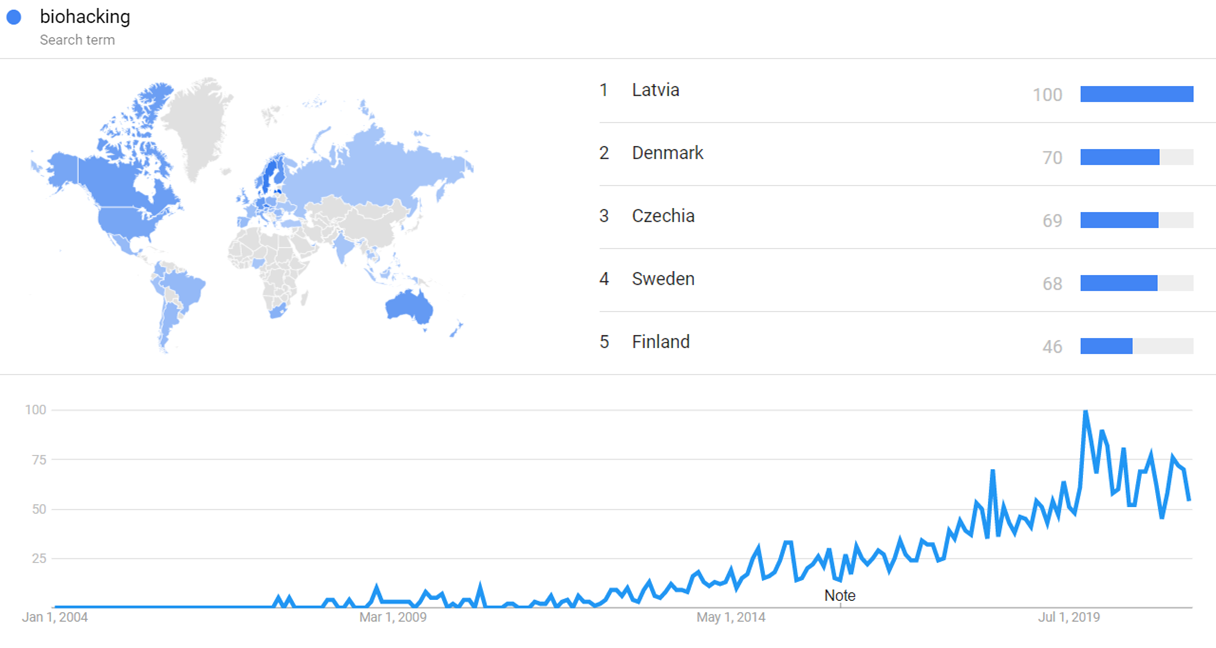

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Biohacking (search term), from January 2004 to Month 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[14]

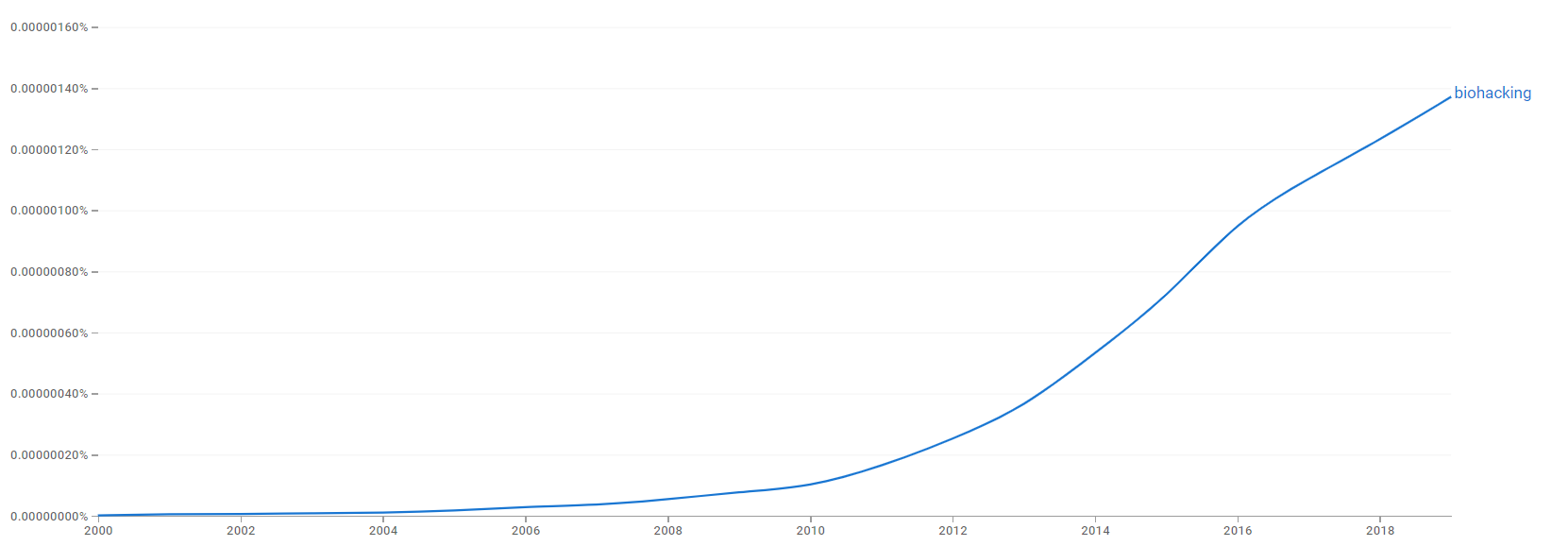

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Biohacking, from 2000 to 2019.[15]

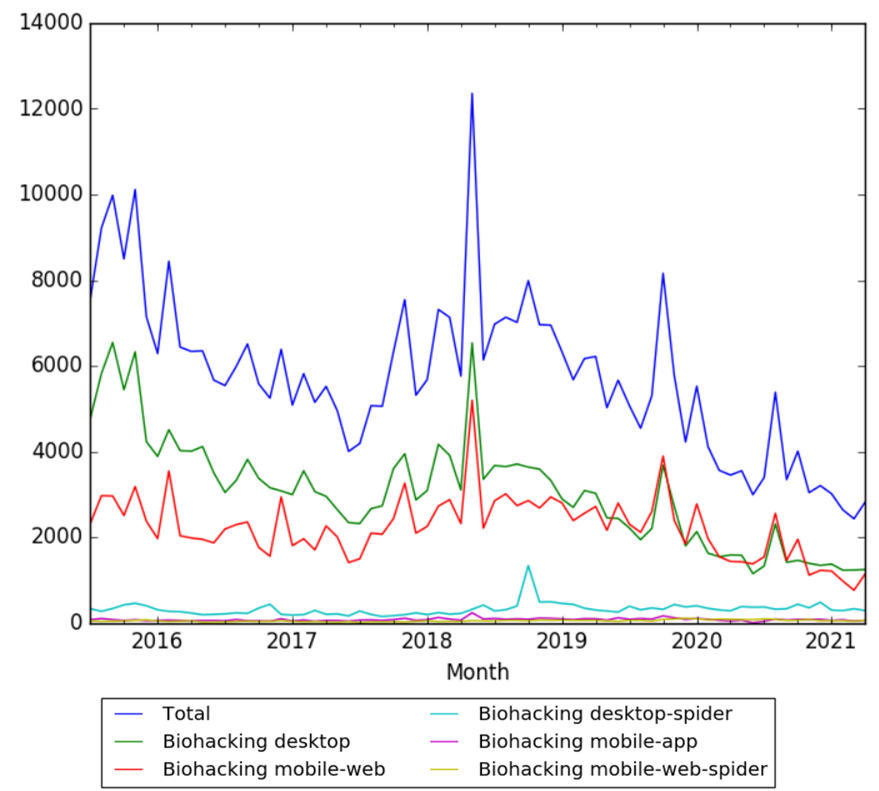

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Biohacking, from July 2015 to April 2021. [16]

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Category | Details | Location/Launch site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930s | Ethical code | The Mertonian ethos is proposed by American sociologist Robert K. Merton as an account of scientist's norms of behavior.[2] | ||

| 1930s | Scientific background | Device implant | German physician Werner Forssmann performs the first clinical cardiac catheterization on himself. He would later win the Nobel Prize.[17] | Germany |

| 1953 | Scientific background | Francis Crick and James Watson discover the DNA double helix structure.[18] | ||

| 1960 | Literature | Manfred Clynes and Nathan Klines publish article Cyborgs and Space.[19] | ||

| 1967 | Scientific background | The first DNA ligase is purified and characterized by the Gellert, Lehman, Richardson, and Hurwitz laboratories.[20] | ||

| 1968 | Scientific background | Robert W. Holley, Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall W. Nirenberg are jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis."[21] | ||

| 1970 | Scientific background | Hamilton Smith and Kent Wilcox announce having isolated and characterized a restriction enzyme (HindII) in a second bacterial species, Haemophilus influenza, and demonstrate that it degrades the DNA of a foreign phage. Restriction enzymes are used for many different purposes in biotechnology. They can be used to splice and insert segments of DNA into other segments of DNA, thereby providing a means to modify DNA and construct new forms.[22] Restriction enzymes find their way into the hands of biohackers.[23] | ||

| 1973 | Scientific background | Stanley Norman Cohen and Herbert Boyer manage to construct a new functional plasmid species in vitro and insert it into an Escherichia coli, thus creating the first transgenic organism.[24] | United States | |

| 1977 | Scientific background | DNA sequencing | British biochemist Frederick Sanger and his team at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge develop the ‘Chain Termination Method’, marking th begining of DNA sequencing. | United Kingdom |

| 1983 | Scientific background | American biochemist Kary Mullis conceives the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as a relatively simple and inexpensive technology used to amplify or make billions of copies of a segment of DNA.[25] | United States | |

| 1983 | Scientific background | Genetically modified plant | A tobacco resistant to antibiotics is grown as the first genetically modified plant (GMP).[26] | |

| 1984 | Literature | Transhumanism | American-Canadian writer William Gibson publishes novel Neuromancer, which is often attributed as the cause in the rise of transhumanism culture popularity in modern times, as well as for coining terminology and ideas that form the basis of modern Cyberpunk and body hacking culture.[27] | United States |

| 1984 | Scientific background | Genetically modified animal | American geneticist Phillip Leder and Timothy Stewart produce a tumor-prone transgenic mouse, used as model of breast cancer.[28] | United States |

| 1984 | Notable comment | Free-culture movement | American writer Stewart Brand coins the slogan "Information wants to be free"[29] against limiting access to information by governmental control, preventing a public domain of information.[30] Brand argues that technology could be liberating rather than oppressing.[31] | United States |

| 1985 | Manifesto | Cyborgs | Donna Haraway’s publishes her Cyborg Manifesto, giving rise to the cyborg theory.[32] | |

| 1986 | Manifesto | Hackers | The Conscience of a Hacker (also known as The Hacker Manifesto) is written as a small essay by a computer security hacker who goes by the handle (or pseudonym) of The Mentor (born Loyd Blankenship). | |

| 1987 | BioArt | DNA data storage | American artist Joe Davis encodes a depiction of the female form into the DNA of living Escherichia coli bacteria, for an artistic venture. This is widely cited as the first experimental demonstration of DNA data storage.[33] | United States |

| 1988 | Notable comment | American Molecular biologist Tom St. John writes an article on the Washington Post titled Playing God in Your Basement, commenting “You can pick up any recent issue of Science magazine, flip through it and find ads for kit after kit of biotechnology techniques”.[11] | United States | |

| 1990 | Scientific background | Genetically modified animal | Herman is born in Leiden, Netherlands, as the world's first transgenic bull. It is the result of a novel in-vitro process by a team of scientists led by Gen Pharming Europe, a GenPharm subsidiary.[34] | Netherlands |

| 1992 | Concept development | The first known use of the word biohacking occurs, and refers to an experimental action done, with the goal of improving the quality of life of a living organism, executed by individuals out of the official scientific and or medical field.[35] | ||

| 1995 | Concept development | Citizen science | Cornell University ornithologist Rick Bonney coins the term citizen science.[36] | United States |

| 1996 | Scientific background | Cloning | Dolly the Sheep is born in Edinburgh.[37][38] | United Kingdom |

| 1998 | Organization | Transhumanism | The global transhumanist foundation Humanity+ is co-founded by Nick Bostrom, to encourage public engagement with the prospects of future technologies being used to enhance human capacities.[39] | |

| 1998 | Organization | Open-source software | The Open Source Initiative is founded by Bruce Perens and Eric S. Raymond. It promotes the usage of open source software.[40][41] | United States |

| 1998 | Manifesto | Transhumanism | The Transhumanist Declaration is written, seeking to place limits and rules on technology that have not even been developed yet.[42] | |

| 1998 | Notable case | Device implant | British cybernetics professor Kevin Warwick implants a radio-frequency identification device (RFID) in his arm, an anti-theft smart label that enables a computer to track Warwick's every move and store codes that allows him to unlock certain doors, computers and even smart phones.[17] | United Kingdom |

| 2000 | Notable case | Genetically modified animal | Chicago artist Eduardo Kac creates transgenic albino rabbit ‘Alba’, which is born in April. The rabbit is part of a transgenic art project called “GFP Bunny”. This project would raise many ethical questions and spark an international controversy about whether Alba should be considered art at all.[43] | United States |

| 2000 | Do-it-yourself biology | Already around this time, some of the synthetic biology pioneers foresee the rise of an amateur branch of ‘garage biology’ parallel to their own field as a consequence of the ever declining cost curves for DNA sequencing and DNA synthesis.[7] | ||

| 2001 | Notable comment | Robert Carlson predicts that, as technologies would become less expensive, faster, and ever simpler to use, they would “first move from academic labs and large biotechnology companies to small businesses, and eventually to the home garage and the kitchen”[7] | ||

| 2002 | Scientific background | The Human Genome Project is conducted. Soon after the human genome is fully sequenced, the first DIY biologists would start tinkering with biological material.[44] | ||

| 2002 | Notable case | Device implant | Ahortly after the Soham murders, English engineer Kevin Warwick offers to implant a tracking device into an 11-year-old girl as an anti-abduction measure. The plan produces a mixed reaction, with endorsement from many worried parents but ethical concerns from children's societies. As a result, the idea would not go ahead.[45] | United Kingdom |

| 2003 | Competition | The International Genetically Engineered Machines is created. It is one of the most important contribution of the early pioneers to the rise of do-it-yourself biology. It would be considered to have done more than any other event to create a generation of biohackers. In these international contests, university student teams compete to make synthetic systems that work in living cells. Several participants at iGEM competitions would become founders of the numerous DIY-Bio groups emerging after 2008.[7] | United States | |

| 2003 | Notable case | DNA sequencing | American synthetic biologist Tom Knight invents the BioBrick plasmids, the most widely used standardized DNA parts, whoch would become central to the international Genetically Engineered Machine competition (iGEM) founded at MIT in the following year.[46][47] | United States |

| 2004 | Notable case | A UT Austin/UCSF iGEM team designs a bacterial system that is switched between different states by red light. The system consists of a synthetic sensor kinase that allows a lawn of bacteria to function as a biological film, such that the projection of a pattern of light on to the bacteria produces a high-definition (about 100 megapixels per square inch), two-dimensional chemical image.[48] | United States | |

| 2004 | Competition | The International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition is created at MIT, with five schools participating.[12] | United States | |

| 2005 | Notable case | Device implant | American biohacker Amal Graafstra implants an RFID chip in his left hand. He is also known for developing human-friendly chips including the first ever implantable NFC chip.[49] | United States |

| 2005 | Notable comment | Rob Carlson writes in an article in Wired: "The era of garage biology is upon us. Want to participate? Take a moment to buy yourself a lab on eBay."[50] In the same year, Carlson becomes the first to build a lab in his garage from equipment bought online.[7] | ||

| 2006 | Notable case | Synthetic biology | An MIT iGEM team manages to modify the normally putrid smell of bacteria so that the cells generate pleasant scents, such as wintergreen and banana.[51][52] | United States |

| 2007 | Diet | New York Magazine reports on a faction of biohackers who believe the fewer calories they consume on a daily basis, the longer they'll live.[53][54] | ||

| 2008 | Do-it-yourself biology | The DIYbio organization is founded in Boston by Jason Bobe and Mackenzie Cowell.[55][56] DIYbio.org is launched as a channel of communication for DIYers who want to build a community around it.[12][57][58] | United States | |

| 2009 | Policy | The United States National Security Council publishes the National Strategy for Countering Biological Threats, which embraces “innovation and open access to the insights and materials needed to advance individual initiatives,” including in “private laboratories in basements and garages.”[59] | United States | |

| 2009 | Do-it-yourself biology | DIY biologists start admitting that ‘do-it-together’ would have been a more appropriate label than Do it yourself.[7] | ||

| 2009 | Project launch | Andy Gracie, Marc Dusseiller and Yashas Shetty launch Hackteria, a webplatform and collection of open source biological art projects. Hackteria has bthe purpose to develop a rich wiki-based web resource for people interested in or developing projects that involve bioart, open source software/hardware, DIY biology, art/science collaborations and electronic experimentation.[60] | ||

| 2009 | Notable case | Paul Vanouse produces his “Latent Figure Protocol" with the DNA of a bacterial plasmid.[61][62] | ||

| 2009 | The United States FBI sponsors a booth and workshop at the 2009 International Genetically Engineered Machine competition in Cambridge, Massachusetts. An FBI agent notes “We're with the U.S. Government […] and we're here to help. Really”. The agency would go on to organize more such meetings in 2011 and 2012.[63] | United States | ||

| 2009 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | La Paillasse is established in Paris as one of the first European Do-it-yourself biology groups.[64] | France |

| 2009 | Organization | BioCurious is established as a project with the purpose to provide shared laboratory space for professional, academic, citizen scientists, as well as anyone else interested in biotech.[65][66] It is a community biology laboratory and nonprofit organization located in Sunnyvale, California.[67] | United States | |

| 2009 | Organization | Citizen science, do-it-yourself biology | American molecular biologist Ellen Jorgensen founds Genspace in Brooklyn, New York, as a non-profit organization and a community biology laboratory. It focuses on supporting citizen science and public access to biotechnology. Genspace is the first nonprofit community biotech lab. | United States |

| 2009 | Notable case | A team of seven Cambridge University manage to engineer bacteria to secrete a variety of coloured pigments, visible to the naked eye. They design standardized sequences of DNA, called BioBrick, and insert them into E. coli bacteria. Each BioBrick part contains genes from existing organisms, enabling the bacteria to produce a colour. By combining these with other BioBricks, bacteria could be programmed to do tasks for humans. Their invention, which they call E. chromi, wins the Grand Prize at the 2009 International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition (iGEM).[68] | United Kingdom | |

| 2010 | Victoria Makerspace is founded by Derek Jacoby and Thomas Gray as a biology community lab.[69] | |||

| 2010 | Organization | BiologiGaragen is founded in Copenhagen in 2010, as a part of Labitat, a vibrant local hackerspace.[64][56] | Denmark | |

| 2010 | Project launch | Education | Ellen Jorgensen initiates Genspace's curriculum of informal science education, leading to the company being named one the World's Top 10 Innovative Companies in Education.[70][71][72] | |

| 2010 | Organization | Genspace opens a Biosafety Level One laboratory,[73][74] the first community biology lab.[75] | ||

| 2010 | Project launch | BioCurious lab opens a campaign on Kickstarter. Led by Eri Gentry, this project manages to to atract both amateur enthusiasts and career scientists alike. In addition to the financial support raised through crowdfunding, many volunteer their time and skills and the laboratory receives significant donations of scientific equipment. It is considered the world's first hackerspace for biotech.[66] | United States | |

| 2011 | Manifesto | Biopunk | American technologist Meredith L. Patterson presents her Biopunk Manifesto.[76][77] | United States |

| 2011 | Project launch | The “Bioluminescence Project” starts as a citizen science initiative at the hackerspace Biocurious in Sunnyvale, California. It is considered a remarkable example of turning community endeavors in DIY-Bio into new business opportunities.[7] | United States | |

| 2011 | Ethical code | Adoption | A code of ethics is adopted by DIYbio.org. This code remains an important touchstone for experiments.[3] | |

| 2012 | TED talk | Ellen Jorgensen gives a TED talk about biohacking, putting the movement on the map.[17][78] | United States | |

| 2012 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | Baltimore Underground Science Space is founded as a non-profit synthetic biology and biotechnology makerspace laboratory for science enthusiasts, hobbyists, and professionals to practice, share and learn about the biological sciences. It is closely aligned with do-it-yourself biology and the Maryland science community generally, and offers courses and lectures in addition to community lab space.[79] | United States |

| 2012 | Do-it-yourself biology | DIY GeneGun 2012 | ||

| 2012 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | Do-it-yourself biology group Dutch DIYBio is founded in the Netherlands.[64] | Netherlands |

| 2012 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | French group La Paillasse organizes a “kick-off” meeting to establish the European DIYBio community (www.diybio.eu), to provide a platform for joint collaborative projects. Further regular meetings would be planned across Europe.[64] |

Europe |

| 2012 | Organization | SyntechBio opens in São Paulo as the first biohacker space in Latin America. It begins as an experiment inside the University of São Paulo "to accelerate the training of students in the synthetic biology area, enhance multidisciplinary studies, and create an open space to develop and share ideas that wouldn’t be normally supported by the academic community in a research context."[12] | Brazil | |

| 2013 | Notable case | Bioluminescence | A team of three biohackers affiliated with Biocurious as well as with Genome Compiler conduct a crowd-sourcing campaign to raise money for developing bioluminescent plants that would glow in the dark. The idea is presented as a step towards a more sustainable future when streets would no longer be lit by electric lamps but by glowing trees. Once the project reaches its goals, each subscriber would receive envelopes with seeds of the genetically modified plants. By June 2013, 6000 hackers would be subscribed, bringing in almost 500.000 dollars to fund the project.[7] | |

| 2013 | Notable case | Device implant | "In 2013, biohacker Tim Cannon had this biosensor implanted into his arm, between the skin and the muscle. The Circadia checks your temperature and your pulse, then syncs this information to an Android device. It also conveys information by lighting up."[80] | |

| 2013 | Organization | Biotech startup company Dangerous Things is founded by Amal Graafstra.[81] It is a Seattle based cybernetic microchip biohacking implant retailer company.[82] | United States | |

| 2013 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | Counter Culture Labs opens in Oakland, California as an open community lab by a group of scientists, tinkerers, biotech professionals, hackers, and citizen scientists. It is a hackerspace for DIY biology and citizen science.[83] | United States |

| 2013 | Notable case | Device implant | DIY biohacker Rich Lee implants headphones in his tragi. He is also known for his work on a vibrating pelvic implant called the Lovetron9000.[84][85][86] | |

| 2013 | Notable case | University of Minnesota researchers develop a new noninvasive system that allows people to control a flying robot using only their mind.[87][88] | United States | |

| 2013 (October) | TED talk | Amal Graafstra gives a TED talk on biohacking.[89] | ||

| 2014 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | The DIYbio Mexico movement is born. Its rise is linked to the synthetic biology and biotechnology research groups that participated in the International Genetically Engineered Machine.[12] | Mexico |

| 2014 | Organization | Citizen science | Hackuarium is founded.[90] It is a not-for-profit association aiming to democratize science through public engagement.[91] | |

| 2014 (May) | TED talk | American entrepreneur Dave Asprey gives a TED talk on how to hack the body to become healthier, smarter and how to lower the biological age.[92] | United States | |

| 2014 | It is estimated that in this year there are 50 DIY biology labs around the world.[93] | |||

| 2014 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | Omni Commons is founded. It is a group of nine collectives in San Francisco's Bay Area devoted to DIY and community education.[94] | |

| 2014 | Literature | Ari R. Meisel publishes Intro to Biohacking.[95] | ||

| 2014 | Organization | Bio Foundry is founded in Australia as the country's first community lab for citizen scientists. It is Australia’s first open-access molecular biology laboratory, offering citizens the opportunity to collaborate in scientific research and development. BioFoundry is also home to BioHackSyd, Australia’s first DIY-Bio group.[96] | Australia | |

| 2015 | Manifesto | James Lee publishes The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks.[97] | ||

| 2015 | Organization | Generic drug | Open Insulin starts as a team of Bay Area biohackers working on newer, simpler, less expensive ways to make insulin. They work on developing the first freely available, open protocol for insulin production.[98] | United States |

| 2015 | Organization | Synthetic biology, biotechnology | Charlottesville Open Bio Lab is founded in Charlottesville, Virginia, with the goal of educating the community about the rising tide of synthetic biology and biotechnology.[99] | United States |

| 2015 | Organization | Four Thieves Vinegar Collective is founded as an anarchist biohacking group.[100] | ||

| 1015 (July) | Organization | BiohackingBA is founded as the first biohacking community in Argentina. It has projects focused on hardware (such as 3D-printed pipettes), arts (like installations with fluorescent bacteria and plants), neuroscience, and bioinformatics.[12] | Argentina | |

| 2015 | Scientific background | Visual prosthesis | Early bionic eyes are produced, consisting in telescopic lens with capability to zoom in and out with blinks and night vision capability-[101] | |

| 2015 | Organization | Neurohacking | Neurohacker Collective is founded with the mission "to advance human quality of life by creating best-in-class well-being products". Its products employ a unique methodology to research and development based on complex systems science. This scientific approach focuses on supporting the body's ability to self-regulate.[102] | United States |

| 2015 | Notable case | Device implant | Swedish biohacker Hannes Sjöblad starts experimenting with NFC chip implants. Sjöblad would go on to implant himself with a chip between his forefinger and thumb and use it to unlock doors, make payments, unlock his phone, and essentially replace anything that is in his pockets.[103] | |

| 2015 | Competition | The International Genetically Engineered Machine is held with 280 teams with more than 2,700 participants from all over the world. "Reminiscent of robotics competitions held for engineers, iGEM uses biological platforms (bacteria, yeast, and plants, among others) to develop solutions and products and to create awareness about society’s problems through synthetic biology".[12] | ||

| 2015 | Organization | Citizen science, biology | ReaGent is founded Ghent, Belgium as a community of citizen scientists who share an open biolab.[104][105] | Belgium |

| 2016 | Notable meeting | Do-it-yourself biology | The first Canadian DIY Biology Summit is conducted.[106] | Canada |

| 2016 | Concept development | Device implant | Norton refers to embedded technology within the human body as to all kinds of implants in and interventions to the human body to enhance performance and health.[107][108] | |

| 2016 | Notable meeting | The first conference to focus specifically on biohacking is announced in Oakland, California.[109] | United States | |

| 2016 | Literature | Caterina Christakos and Sue Bell publish Biohackers Journal - Keeping Track of Your Biohacking Stack.[110] | ||

| 2016 | Notable case | Transplant | American biohacker Josiah Zayner, sick of suffering from severe stomach pain, attempts a full fecal microbiota transplant on himself.[111] Afterward, he would claim the experiment left him feeling better.[59] | United States |

| 2016 | Organization | The Latin American Network of Biohacker Spaces is launched at the end of the year. It starts including groups from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, further expanding through the region.[12] | ||

| 2016 (November) | TED talk | Nuria Conde gives a TED talk in Barcelona, on how to become a biohacker.[112] | Spain | |

| 2017 | Notable case | Device implant | Workers at Wisconsin-based tech company Three Square Market agree to have microchips implanted in their hands in order to enter the office, log into computers and even buy a snack or two with just a swipe of a hand. The microchip uses radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology.[113] | United States |

| 2017 | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology | top is founded in Berlin as a transdisciplinary project place for art and science. Its members use borrowed, recycled and home-built equipment to recreate a typical do-it-yourself biology lab and bring biology to the public.[114] | Germany |

| 2017 | Organization | ChiTownBio is founded as Chicago's first community biolab. It is "dedicated to putting the knowledge, skills, and tools of biotechnology into the hands of all Chicagoans who want to explore the living world and use it to benefit our community".[115] | United States | |

| 2017 | Organization | Ellen Jorgensen founds Biotech Without Borders,[70] a Brooklyn, New York based nonprofit public charity dedicated to enabling communities underrepresented in the biotechnology field to gain hands-on biotech lab experience.[116] Biotech Without Borders focuses on providing a Biosafety Level 2 lab space, distributing biotech resources to labs worldwide, and engaging the public through hands-on lab classes, workshops, and events.[117] | United States | |

| 2017 | The CSA Ethics Working Group Resource Collection is tarted as a collection of tools by the Ethics Working Group of the Citizen Science Association. This collection is aimed at all scientists, including citizen scientists and biohackers, who can use for ethics. It includes codes of ethics, consent form templates, recorded webinars, training, guides, technologies, and related sites and blogs.[118] | United States | ||

| 2017 (October) | TED talk | Swedish biohacker Jowan Österlund gives a TED talk in Bratislava, explaining how seamless interection between body and technology should work in the future.[119] | Slovakia | |

| 2018 | Statistics | Do-it-yourself biology | By this time, DIYbio.org lists 44 biohacking labs in North America, 31 in Europe and 17 across Asia, South America and Oceania.[44][56] | Worldwide |

| 2018 (June) | Notable case | Device implant | Sydney biohacker Meow-Ludo Disco Gamma Meow-Meow implants an Opal card chip into his hand. However, he is penalized despite implant returning a "valid tap-on", and is fined US$220 for failing to comply with existing transit laws.[120][121][122] | Australia |

| 2018 (July) | TED talk | Ben Greenfield gives a TED talk sharing tips for longevity and how to biohack the body.[123] | ||

| 2019 (May) | Notable case | Belgium-based Russian biohacker named Vladimir Kaigorodov injects himself with DNA from Dolly the Sheep, claiming that it came to his body "as a kind of new stage in human evolution".[124] | Belgium | |

| 2020 | Television | German techno-thriller television series Biohackers is released on Netflix. It depicts illegal genetic experimentation.[125] | Germany | |

| 2020 | Statistics | As of date, North America holds the dominant share of the overall revenue owing to the presence of several key biohacking market players in the region, especially in the United States. Europe holds the second-largest revenue share.[126] | North America | |

| 2028 | Statistics | The global biohacking market size is anticipated to reach US$ 63.7 billion by this year.[126] | ||

| 2018 (July 7) | Organization | Do-it-yourself biology, citizen science | BIOOK is founded in Spain. Based on the do-it-yourself biology movement and on Citizen Science, it is a non-profit association that aims to promote social innovation, "creating ecosystems for citizens to participate and enjoy scientific-cultural production, eliminating boundaries between biology and other disciplines."[127] | {Spain |

| 2020 (January 7) | TED talk | Martin Kremmer gives a TED talk in Copenhagen, recounting his experience with biohacking.[128] | Denmark |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

- [1]

- [2]

- check for articles here

- [3]

- more events

- more events

- [4]

- Genbank

- genomic database, community lab, online sharing tool, cracking of dna code, hacker, open science, open source, open access, citizen science, online cooperative science (science 2.0).

- Ilaria Capua open access database

- [5]

- [6]

- [7]

- [8]

- Body hacking

- Category:Do it yourself

- Body hacking

- Neurohacking

- [9]

- DIYbio (organization)

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "The Rise of the Do-it-Yourself Movement in the 1950's". Make it Mid Century. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Delfanti, Alessandro (7 May 2013). Biohackers: The Politics of Open Science. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-3280-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zettler, Patricia J.; Guerrini, Christi J.; Sherkow, Jacob S. (5 July 2019). "Regulating genetic biohacking". Science. 365 (6448): 34–36. doi:10.1126/science.aax3248.

- ↑ "The Evolution Of The Biohacking Ecosystem". TechCrunch. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "Richard Stallman and The History of Free Software and Open Source". Curious Minds Podcast. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ David, Derick (2 July 2020). "How To Neurohack Your Mind In 15 Minutes". Medium.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Keulartz, Jozef; van den Belt, Henk (December 2016). "DIY-Bio – economic, epistemological and ethical implications and ambivalences". Life Sciences, Society and Policy. 12 (1): 7. PMID 27237829.

- ↑ "20 Years of Open Source". GitLab. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ Onaolapo, Adejoke Yetunde; Obelawo, Adebimpe Yemisi; Onaolapo, Olakunle James (May 2019). "Brain Ageing, Cognition and Diet: A Review of the Emerging Roles of Food-Based Nootropics in Mitigating Age-Related Memory Decline". Current Aging Science. 12 (1): 2–14. ISSN 1874-6098. doi:10.2174/1874609812666190311160754.

- ↑ Katz, Sylvan. "Forum: Roses are black, violets are green - The emergence of amateur genetic engineers". New Scientist. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Vargo, Marc E. (11 August 2017). The Weaponizing of Biology: Bioterrorism, Biocrime and Biohacking. McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4766-2933-9.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Sluys, Edgar Andrés Ochoa Cruz, Oscar Joel de la Barrera Benavidez, Manuel Giménez, Maria Chavez, Marie-Anne Van (2 May 2016). "The biohacking landscape in Latin America". O’Reilly Media. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "Doing Biotech in My Bedroom". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking". Google Trends. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking". books.google.com. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "The brave new world of biohacking". america.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "1953: DNA Double Helix". Genome.gov. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ "Cyborgs and Space". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ Shuman, Stewart (June 2009). "DNA Ligases: Progress and Prospects". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (26): 17365–17369. doi:10.1074/jbc.R900017200.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Made by bacteria restriction enzymes are key to cloning DNA". WhatisBiotechnology.org. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ↑ "(PDF) Roses are black, violets are green - The emergence of amateur genetic engineers". ResearchGate. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ↑ "TRANSGENIC ANIMALS" (PDF). web.wpi.edu. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "1983 | Invention of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology for amplifying DNA". Genome: Unlocking Life's Code. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ Zeljezić, D (November 2004). "[Genetically modified organisms in food--production, detection and risks].". Arhiv za higijenu rada i toksikologiju. 55 (4): 301–12. PMID 15584557.

- ↑ "Neuromancer | Summary & Cultural Impact". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ↑ Hanahan, Douglas; Wagner, Erwin F.; Palmiter, Richard D. (15 September 2007). "The origins of oncomice: a history of the first transgenic mice genetically engineered to develop cancer". Genes & Development. pp. 2258–2270. doi:10.1101/gad.1583307. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Edge 338", Edge (338), retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Wagner, R Polk, Information wants to be free: intellectual property and the mythologies of control (PDF), University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Baker, Ronald J (2008-02-08), Mind over matter: why intellectual capital is the chief source of wealth, p. 80, ISBN 9780470198810.

- ↑ "Close Reading of Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway | Darat al Funun". daratalfunun.org. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ NadisFeb. 18, Steve (18 February 2020). "Hardy microbe's DNA could be a time capsule for the ages". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ↑ SELTZER, RICHARD (14 February 1994). "First transgenic bull sires transgenic calves". Chemical & Engineering News Archive. p. 30. doi:10.1021/cen-v072n007.p030. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "Blog | MÁDARA Organic Skincare". www.madaracosmetics.com. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ Gura, Trisha (April 2013). "Citizen science: Amateur experts". Nature. 496 (7444): 259–261. ISSN 1476-4687. doi:10.1038/nj7444-259a.

- ↑ "The Life of Dolly | Dolly the Sheep". Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Dolly the Sheep". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Nick Bostrom | Edge.org". www.edge.org. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "About the Open Source Initiative | Open Source Initiative". archive.ph. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "History of the OSI | Open Source Initiative". opensource.org. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ Feb. 4th, Bill Gerken. "Biohacking - Technology and the Human Body". Reporter. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "Transgenic bunny by Eduardo Kac". www.genomenewsnetwork.org. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Contributor, External (7 November 2018). "Biohacking: Democratization of Science or Just a Quirky Hobby?". Labiotech.eu.

- ↑ "Tracking device implant criticised". Community Care. 5 September 2002. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ Knight, Thomas (2003). "Tom Knight (2003). Idempotent Vector Design for Standard Assembly of Biobricks". hdl:1721.1/21168.

- ↑ Shetty, Reshma P; Endy, Drew; Knight, Thomas F (December 2008). "Engineering BioBrick vectors from BioBrick parts". Journal of Biological Engineering. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1754-1611-2-5.

- ↑ "Coliroid - parts.igem.org". parts.igem.org. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ↑ "The xNT implantable NFC chip". Indiegogo. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ Carlson, Rob (May 2005). "Splice It Yourself: Who needs a geneticist? Build your own lab.". Wired.

- ↑ Dixon, James; Kuldell, Natalie (2011). "BioBuilding". Methods in Enzymology. 497: 255–271. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385075-1.00012-3.

- ↑ "BioBuilding: Using Banana-Scented Bacteria to Teach Synthetic Biology". Methods in Enzymology. 497: 255–271. 1 January 2011. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385075-1.00012-3.

- ↑ Zaczek, Alyssa. "What's a biohacker? You might already be one.". St. Cloud Times. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "The Ultra-Extreme Calorie Restriction Diet Test -- New York Magazine - Nymag". New York Magazine. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "DIYbio on the News Hour". youtube.com. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Meyer, Morgan (May 2018). "Biologie et médecine « do-it-yourself »: Histoire, pratiques, enjeux". médecine/sciences. 34 (5): 473–479. doi:10.1051/medsci/20183405022.

- ↑ "DIYbio.org". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ Vargo, Marc E. (11 August 2017). The Weaponizing of Biology: Bioterrorism, Biocrime and Biohacking. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2933-9.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Samuel, Sigal (25 June 2019). "How biohackers are trying to upgrade their brains, their bodies — and human nature". Vox. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ "About « Hackteria". hackteria.org. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "Fabricating the DNA Fingerprint". Art21 Magazine. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "The latent figure protocol - A photo-essay". researchgate.net. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ Wolinsky, Howard (June 2016). "The FBI and biohackers: an unusual relationship: The FBI has had some success reaching out to the DIY biology community in the USA , but European biohackers remain skeptical of the intentions of US law enforcement". EMBO reports. 17 (6): 793–796. doi:10.15252/embr.201642483.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 Seyfried, Günter; Pei, Lei; Schmidt, Markus (June 2014). "European do‐it‐yourself (DIY) biology: Beyond the hope, hype and horror". BioEssays. 36 (6): 548–551. doi:10.1002/bies.201300149.

- ↑ "BioCurioso". stringfixer.com. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Välikangas, Liisa; Gibbert, Michael (11 September 2015). Strategic Innovation: The Definitive Guide to Outlier Strategies. FT Press. ISBN 978-0-13-398014-1.

- ↑ Välikangas, L.; Gibbert, M. (2015). Strategic Innovation: The Definitive Guide to Outlier Strategies. FT Press. pp. pt160–167. ISBN 978-0-13-398014-1. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ↑ "ALEXANDRA DAISY GINSBERG". www.daisyginsberg.com. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ↑ "UVic Torch Alumni Magazine - Autumn 2013". Issuu.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "Ellen Jorgensen". Global Community Bio Summit. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ↑ "Support Us". Genspace. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ↑ "The World's Top 10 Most Innovative Companies In Education". Fast Company. 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ↑ Kean, Sam (2 September 2011). "A Lab of Their Own". Science. 333 (6047): 1240–1241. doi:10.1126/science.333.6047.1240.

- ↑ "DIY Biotech Hacker Space Opens in NYC". Wired. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "DIY Biotech Hacker Space Opens in NYC". Wired. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ "A Biopunk Manifesto - Meredith Patterson".

- ↑ "Can Hobbyists and Hackers Transform Biotechnology?". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Ellen Jorgensen: Biohacking -- you can do it, too". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "Baltimore Underground Science Space (BUGSS)". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "You've gotta see these human cyborgs (WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGES)". CNET. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Dangerous Things". Dangerous Things. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ↑ "Implantable RFID company Dangerous Things looks outside the body with hacker-friendly Bluetooth switch". GeekWire. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Counter Culture Labs". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "Why This Guy Implanted Headphones In His Ears". Popular Science. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ Isaacson, Betsy (26 June 2013). "Man Implants Invisible Headphone In His Ear". HuffPost. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ Katz, Leslie. "Surgically implanted headphones are literally 'in-ear'". CNET. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Mind-controlled quadcopter flies using imaginary fists". New Atlas. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ "Univ. of Minn. develops mind-controlled flying robot". youtube.com. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking - the forefront of a new kind of human evolution: Amal Graafstra at TEDxSFU". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ Calvo, Samuel Jay (13 June 2016). "Luc Henry | Co-Founder | Hackuarium". Medium. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Hackuarium". linkedin.com. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Hacking yourself: Dave Asprey at TEDxConstitutionDrive". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ Jemielniak, Dariusz; Przegalinska, Aleksandra (18 February 2020). Collaborative Society. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-35645-9.

- ↑ "5 Years After Occupy Oakland, Still Fighting for the 99 Percent". KQED. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ Meisel, Ari R. Intro to Biohacking. Createspace Independent Pub. ISBN 978-1-5025-1546-9.

- ↑ "Bio Foundry". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ Lee, James. The Biohacking Manifesto: The Scientific Blueprint for a Long, Healthy and Happy Life Using Cutting Edge Anti-Aging and Neuroscience Based Hacks. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5121-2127-8.

- ↑ "Open Insulin". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "Open Bio Labs hosts conference for community-based science". www.cvilletomorrow.org. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ "Four Thieves Vinegar Collective debuts 3D printed chemical reactor for homemade medicine". 3D Printing Industry. 13 August 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ "Zoom Contact Lens Magnifies Objects at the Wink of an Eye". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ Collective, Neurohacker. "Back To School Biohacking Boot Camp". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ "Au pays des espèces en voie de disparition". Les Echos (in français). 2016-02-19. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ↑ "ReaGent - Open DIY labo voor citizen science in Gent". ReaGent. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "ReaGent". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ Government of Canada, Innovation. "The Science of Health - Science.gc.ca". science.gc.ca. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "The beginners' guide to biohacking". inews.co.uk. 19 November 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ Gangadharbatla, Harsha (May 2020). "Biohacking: An exploratory study to understand the factors influencing the adoption of embedded technologies within the human body". Heliyon. 6 (5): e03931. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03931.

- ↑ "Biohack the Planet Conference". Biohack the Planet. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ Christakos, Caterina; Bell, Sue (22 June 2016). Biohackers Journal - Keeping Track of Your Biohacking Stack: Biohacking Journal. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5348-5474-1.

- ↑ Duhaime-Ross, Arielle (May 4, 2016). "A Bitter Pill". The Verge. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Cómo convertirse en un biohacker | Nuria Conde | TEDxBarcelona". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ News, A. B. C. "Tech company workers agree to have microchips implanted in their hands". ABC News. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ↑ "top". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "ChiTownBio". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "About Us". Biotech Without Borders. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ↑ "Our Mission And History". Biotech Without Borders. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ↑ "CSA Ethics Working Group Resource Collection". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "Biohacking - the next step in human evolution or a dead end? | Jowan Österlund | TEDxBratislava". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ Press, Australian Associated (16 March 2018). "Bodyhacking scientist who implanted Opal card chip guilty of fare evasion". the Guardian. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Sydney bio-hacker has travel card implanted into hand". www.abc.net.au. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ Hevesi, Bryant (27 June 2017). "Sydney bio-hacker has Opal travel card chip inserted in his HAND". Mail Online. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ "Can you Hack Your Biological Age? | Ben Greenfield". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "Russian biohacker injects himself with Dolly the sheep's DNA". Biohackinfo. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "'Biohackers' play god in German Netflix series | DW | 20.08.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Markets, Research and (23 August 2021). "Global Biohacking Market Forecasts and Outlook 2021-2028: Forensics Laboratories Segment Recorded Revenue Share of 28% in 2020, with High Product Adoption for Monitoring Patient Health Conditions". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ "Biook". sphere.diybio.org. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ "My experience with bio-hacking | Martin Kremmer | TEDxCopenhagen". youtube.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.