Difference between revisions of "Timeline of animal welfare and rights"

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

|100s||Greek medical researcher and philosopher [[wikipedia:Galen|Galen's]] experiments on live animals help establish vivisection as a widely used scientific tool.<ref name="sharp" /><ref name="vivhist">{{cite web |url=http://science.jrank.org/pages/7246/Vivisection-An-ancient-history.html |title=Vivisection - An Ancient History |accessdate=April 23, 2016}}</ref> | |100s||Greek medical researcher and philosopher [[wikipedia:Galen|Galen's]] experiments on live animals help establish vivisection as a widely used scientific tool.<ref name="sharp" /><ref name="vivhist">{{cite web |url=http://science.jrank.org/pages/7246/Vivisection-An-ancient-history.html |title=Vivisection - An Ancient History |accessdate=April 23, 2016}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |675||Japanese [[wikipedia:Emperor Tenmu|Emperor Tenmu]], a devout Buddhist, bans eating meat (with exceptions for fish and wild animals).<ref name="watanabe" />|| | + | |675||Japanese [[wikipedia:Emperor Tenmu|Emperor Tenmu]], a devout Buddhist, bans eating meat (with exceptions for fish and wild animals).<ref name="watanabe" />|| {{w|Japan}} |

|- | |- | ||

|Early 1600s|| Philosopher and scientist [[wikipedia:René Descartes|René Descartes]] argues that animals are machines without feeling, and performs biological experiments on living animals.<ref name="animalcon" /> | |Early 1600s|| Philosopher and scientist [[wikipedia:René Descartes|René Descartes]] argues that animals are machines without feeling, and performs biological experiments on living animals.<ref name="animalcon" /> | ||

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

|2013||The [[wikipedia:Nonhuman Rights Project|Nonhuman Rights Project]] files the first-ever lawsuits on behalf of [[wikipedia:chimpanzee|chimpanzee]]s, demanding courts grant them the right to bodily liberty via a writ of ''[[wikipedia:habeas corpus|habeas corpus]]''.<ref name="nhrp">{{cite web |url=http://www.nonhumanrightsproject.org/2013/11/30/press-release-re-nhrp-lawsuit-dec-2nd-2013/ |title=First-Ever Lawsuits Filed on Behalf of Captive Chimpanzees |accessdate=April 21, 2016}}</ref> The petitions are denied and the cases move on to [[wikipedia:appellate court|appellate court]]s.<ref name="mountain">{{cite web |url=http://www.nonhumanrightsproject.org/2013/12/10/new-york-cases-judges-decisions-and-next-steps/ |author=Michael Mountain |title=New York Cases – Judges’ Decisions and Next Steps |date=December 10, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2016}}</ref> | |2013||The [[wikipedia:Nonhuman Rights Project|Nonhuman Rights Project]] files the first-ever lawsuits on behalf of [[wikipedia:chimpanzee|chimpanzee]]s, demanding courts grant them the right to bodily liberty via a writ of ''[[wikipedia:habeas corpus|habeas corpus]]''.<ref name="nhrp">{{cite web |url=http://www.nonhumanrightsproject.org/2013/11/30/press-release-re-nhrp-lawsuit-dec-2nd-2013/ |title=First-Ever Lawsuits Filed on Behalf of Captive Chimpanzees |accessdate=April 21, 2016}}</ref> The petitions are denied and the cases move on to [[wikipedia:appellate court|appellate court]]s.<ref name="mountain">{{cite web |url=http://www.nonhumanrightsproject.org/2013/12/10/new-york-cases-judges-decisions-and-next-steps/ |author=Michael Mountain |title=New York Cases – Judges’ Decisions and Next Steps |date=December 10, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2016}}</ref> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |2013||The UK legislation to protect animals in research, The [[wikipedia:Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986|Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986]], is amended to protect "...all living vertebrates, other than man, and any living cephalopod." Previously, the only protected invertebrate was the common octopus.|| | + | |2013||The UK legislation to protect animals in research, The [[wikipedia:Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986|Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986]], is amended to protect "...all living vertebrates, other than man, and any living cephalopod." Previously, the only protected invertebrate was the common octopus.|| {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

|2014||India becomes the first country in Asia to ban testing cosmetics on animals as well as imports of animal-tested cosmetics.<ref name="cronin">{{cite web |url=https://www.thedodo.com/india-bans-cosmetic-testing-764115558.html |author=Melissa Cronin |title=This is the First Country in Asia to Ban All Cosmetics Tested on Animals |date=October 14, 2014 |accessdate=April 24, 2016}}</ref> | |2014||India becomes the first country in Asia to ban testing cosmetics on animals as well as imports of animal-tested cosmetics.<ref name="cronin">{{cite web |url=https://www.thedodo.com/india-bans-cosmetic-testing-764115558.html |author=Melissa Cronin |title=This is the First Country in Asia to Ban All Cosmetics Tested on Animals |date=October 14, 2014 |accessdate=April 24, 2016}}</ref> | ||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

|2016||Cellular agriculture company Memphis Meats announces the creation of the first in vitro meatball.<ref name="hanson" /> | |2016||Cellular agriculture company Memphis Meats announces the creation of the first in vitro meatball.<ref name="hanson" /> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 13, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! "animal welfare" | ||

| + | ! "animal rights" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 48,300 || 1,190 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1992 || 8,260 || 1,170 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1994 || 8,930 || 1,330 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1996 || 9,130 || 1,510 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1998 || 9,230 || 1,870 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 49,100 || 2,490 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2002 || 16,400 || 2,940 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004 || 17,300 || 3,030 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || 21,700 || 3,160 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || 27,600 || 3,990 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 56,400 || 4,970 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || 52,300 || 6,380 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2014 || 52,300 || 10,500 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2016 || 45,000 || 13,900 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || 47,900 || 18,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 35,400 || 23,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Animal welfare and rights gscho.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google trends === | ||

| + | The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Animal welfare (topic) and Animal rights (topic).<ref>{{cite web |title=Animal welfare and Animal rights |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F017kd4,%2Fm%2F0h4xw_ |website=trends.google.com |access-date=6 January 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Animal welfare and Animal rights.jpeg|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Animal welfare and rights from 1900 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Animal welfare and rights |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Animal+welfare+and+rights&year_start=1900&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=1&case_insensitive=true |website=books.google.com |access-date=13 January 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Animal welfare and rights.jpeg|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Animal welfare }}, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Animal welfare |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Animal+welfare&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=3 February 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Animal welfare wv.jpeg|thumb|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

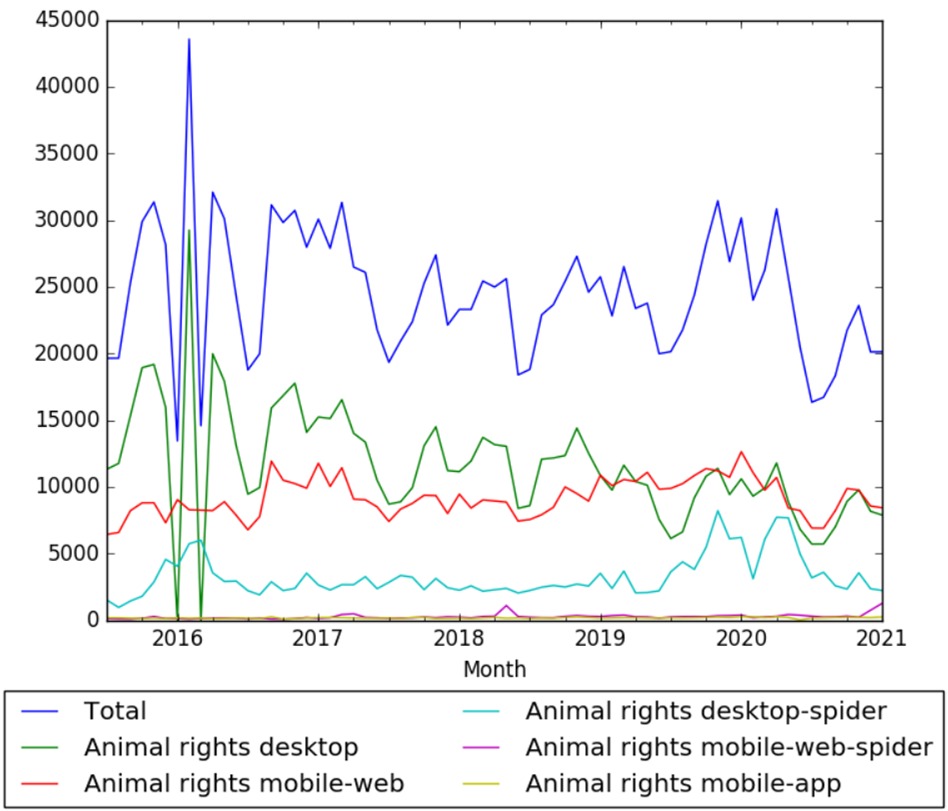

| + | The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article {{w|Animal rights }}, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Animal rights |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?page=Animal+rights&allmonths=allmonths-api&language=en&drilldown=all |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=3 February 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Animal rights wv.jpeg|thumb|center|500px]] | ||

| Line 196: | Line 266: | ||

* [https://www.facebook.com/groups/mariave.4.9.17.groups.gr/permalink/1870993819726201/ WORLDWIDE VEGANS AND ANIMAL-HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP] Facebook group | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/mariave.4.9.17.groups.gr/permalink/1870993819726201/ WORLDWIDE VEGANS AND ANIMAL-HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP] Facebook group | ||

* [https://www.facebook.com/groups/VeganColorado/permalink/3442094802500643/ Vegan Colorado] Facebook group | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/VeganColorado/permalink/3442094802500643/ Vegan Colorado] Facebook group | ||

| + | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/387735551652195/permalink/1028962984196112 Animal Rights Strategy Group] Facebook group | ||

* [https://www.facebook.com/groups/321110578261972/permalink/1191992141173807 Animal Rights Strategy Group (Original)] Facebook group | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/321110578261972/permalink/1191992141173807 Animal Rights Strategy Group (Original)] Facebook group | ||

| + | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/2562498527300216/permalink/2689396674610400 Muslim Vegans] Facebook group | ||

| + | * [https://www.facebook.com/groups/139883229505889/permalink/1625750087585855 Intermittent Fasting for Vegans] Facebook group | ||

===What the timeline is still missing=== | ===What the timeline is still missing=== | ||

Latest revision as of 07:42, 9 December 2022

This page is a timeline of major events in the history of animal welfare and animal rights.

Contents

Overview

| Period | Description |

|---|---|

| c.14000-1000 BCE | The domestication of animals begins with dogs. From 8500 to 1000 BCE, cats, sheep, goats, cows, pigs, chickens, donkeys, horses, silkworms, camels, bees, ducks, and reindeer are domesticated by various civilizations.[1] |

| 1000 BCE-700 | Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism teach ahimsa, nonviolence toward all living beings. Many adherents of these religions forego meat-eating and animal sacrifice, and – in the case of Jainism – take great precautions to avoid injuring animals. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are less comprehensive in their concern for animals, but include some provisions for humane treatment.[2] A number of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers advocate for vegetarianism and kindness toward animals.[3] Vivisection for scientific and medical purposes begins in ancient Greece.[4] Under the influence of Buddhism, a ban on meat-eating is instated in Japan.[5] |

| 1600-1800 | Philosophers take up the question of animals and their treatment, some arguing that they are sentient beings who deserve protection.[6][7][8] The first modern animal protection laws are passed in Ireland and the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[9] |

| 1800-1914 | British Parliament passes the first national animal protection legislation, and the first animal protection and vegetarian organizations form in the U.S. and U.K..[10] The American and British anti-vivisection movements grow in the late 19th century, culminating in the Brown Dog affair and declining sharply thereafter.[11] The Japanese taboo against meat-eating dies out under the Meiji Restoration.[12] |

| 1914-1966 | The use of animals grows tremendously with the beginning of intensive animal agriculture in the 1920s[13] and the increasing role of animal experimentation in science and cosmetics.[14] Media coverage of animal abuses spurs concern over animal welfare in the U.S. and U.K., and helping bring about the first federal animal welfare legislation in the U.S.[15][16] The theoretical possibility of in vitro animal products is recognized.[17] |

| 1966-2016 | Consumption of intensively farmed animal products booms worldwide, with global meat production rising from approximately 78 million tons in 1963 to 308 million tons in 2014.[18] In the US and Europe, books, documentaries, and media coverage of controversies surrounding animal cruelty boost the animal rights and welfare movements,[19][20][21][22] while destructive direct actions by groups like the Animal Liberation Front draw public rebuke and government crackdown.[23][24] Research on in vitro animal products gains traction,[17] resulting in the first in vitro meats.[25][26] Beginning in the late 1980s, Europe takes the lead in animal welfare reform.[23] In the West and some other countries, public interest in animal welfare, animal rights, and plant-based diets increases significantly.[27][28][29][30] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event | Country or region |

|---|---|---|

| c. 530 BCE | Greek philosopher Pythagoras is the first in a line of several Greek and Roman philosophers to teach that animals have souls and advocate for vegetarianism.[3] | |

| c. 269-c. 232 BCE | Indian emperor Ashoka converts to Buddhism and issues edicts advocating vegetarianism and offering protections to wild and domestic animals.[31] | |

| 100s | Greek medical researcher and philosopher Galen's experiments on live animals help establish vivisection as a widely used scientific tool.[4][32] | |

| 675 | Japanese Emperor Tenmu, a devout Buddhist, bans eating meat (with exceptions for fish and wild animals).[5] | Japan |

| Early 1600s | Philosopher and scientist René Descartes argues that animals are machines without feeling, and performs biological experiments on living animals.[6] | |

| 1635 | The Parliament of Ireland passes "An Act against Plowing by the Tayle, and pulling the Wooll off living Sheep", one of the first known pieces of animal protection legislation.[9] | |

| 1641 | Regulations against “Tirranny or Crueltie” toward domestic animals are included in the Massachusetts Body of Liberties.[9] | |

| 1687 | The Japanese ban on eating meat, which had waned with the arrival of Portuguese and Dutch missionaries, is reintroduced by the Tokugawa shogunate. Killing animals is also prohibited.[5] | |

| 1780 | In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation philosopher Jeremy Bentham argues for better treatment of animals on the basis of their ability to feel pleasure and pain, famously writing, "The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?"[8] | |

| 1822 | Led by Richard Martin, British Parliament passes the "Act to Prevent the Cruel and Improper Treatment of Cattle".[33] | |

| 1824 | Richard Martin, along with Reverend Arthur Broome and abolitionist Member of Parliament William Wilberforce, founds the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (now the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals), the world's first animal protection organization.[33] | |

| 1830s | Early vegan and anti-vivisectionist Lewis Gompertz leaves the SPCA to found the Animals' Friend Society, opposing all uses of animals which are not for their benefit.[34] | |

| 1835 | Britain passes its first Cruelty to Animal Act after lobbying from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, expanding existing legislation to protect bulls, dogs, bears, and sheep, and prohibit bear-bating and cock-fighting.Template:Fix/category[citation needed] | |

| 1847 | The term "vegetarian" is coined and the Vegetarian Society is founded in Britain.[35] | |

| 1859 | Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species is published, demonstrating that humans are the evolutionary descendants of non-human animals.[36] | |

| 1866 | The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is established.[15] | |

| 1866 onwards | Under the Meiji Restoration and renewed contact with the West, the Japanese taboo against meat-eating is actively discouraged by the government. Meat-eating soon becomes the norm.[12] | |

| 1875 | Frances Power Cobbe founds the National Anti-Vivisection Society in Britain, the world's first anti-vivisection organization.[11] | |

| 1876 | After lobbying from anti-vivisectionists, Britain passes the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876, the first piece of national legislation to regulate animal experimentation.[16] | |

| 1877 | Anna Sewell's Black Beauty, the first English novel to be written from the perspective of a non-human animal, spurs concern for the welfare of horses.[11] | |

| 1892 | Social reformer Henry Salt publishes Animals' Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress, an early exposition of the philosophy of animal rights.[10] | |

| 1903-1910 | The Brown Dog affair brings anti-vivisection to the forefront of public debate in Britain.[11] | |

| 1923 | Intensive animal farming begins when Celia Steele raises her first flock of chickens for meat.[13] | |

| 1944 | Donald Watson coins the word "vegan" and founds The Vegan Society in Britain.[35] | |

| Early 1950s | Willem van Eelen recognizes the possibility of generating meat from tissue culture.[17] | |

| 1955 | The Society for Animal Protective Legislation (SAPL), the first organization to lobby for humane slaughter legislation in the US, is founded.[15] | |

| 1958 | The American Humane Slaughter Act is passed.[15] | |

| 1960 | Indian parliament passes its first national animal welfare legislation, The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.[37] | |

| 1964 | The Hunt Saboteurs Association is founded in England to sabotage hunts and oppose bloodsports.[38] | |

| 1964 | Ruth Harrison's Animal Machines, which documents the conditions of animals on industrial farms, helps to galvanize the animal movement in Britain.[23] | |

| 1964 | Largely due to the outcry following Animal Machines, British Parliament forms the Brambell Committee to investigate animal welfare. The Committee concludes that animals should be afforded the Five Freedoms, which consist of the animal's freedom to “have sufficient freedom of movement to be able without difficulty to turn around, groom itself, get up, lie down, [and] stretch its limbs.”[23][39] | |

| 1966 | Following public outcry over the cases of Pepper and other mistreated animals, the American Animal Welfare Act is passed. This legislation sets minimum standards for handling, sale, and transport of dogs, cats, nonhuman primates, rabbits, hamsters, and guinea pigs, and instates conservative regulations on animal experimentation.[16] | |

| 1970 | Animal rights activist Richard Ryder coins the term "speciesism" to describe the devaluing of nonhuman animals on the basis of species alone.[40] | |

| 1971 | The United States Department of Agriculture excludes birds, mice, and rats - which make up the vast majority of animals used in research - from protection under the Animal Welfare Act.[41][42] | |

| 1974 | Ronnie Lee and Cliff Goodman of the Band of Mercy, a militant group founded by former members of the Hunt Saboteurs Association, are jailed for firebombing a British animal research center.[43] | |

| 1974 | The Council of Europe passes a directive requiring that animals be rendered unconscious before slaughter.[23] | |

| 1974 | Henry Spira founds Animal Rights International after attending a course on animal liberation given by Peter Singer.[44] | |

| 1975 | Peter Singer publishes Animal Liberation, whose depictions of the conditions of animals on farms and in laboratories and utilitarian arguments for animal liberation are to have a major influence on the animal movement.[19] | |

| 1976 | The European Convention for the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes, which mandates that animals be kept in conditions meeting their “physiological and ethological needs”, is passed.[23] | |

| 1976 | Released from prison, Ronnie Lee founds the Animal Liberation Front in Britain, which soon spreads to the US.[43] | |

| 1976-1977 | Under the leadership of Henry Spira, Animal Rights International leads a successful campaign to end harmful experiments performed on cats at the American Museum of Natural History.[45] | |

| 1980 | A campaign by Animal Rights International opposing Draize tests performed on rabbits by the cosmetics company Revlon results in Revlon making a $250,000 grant to Rockefeller University to research alternatives to animal experimentation. Several other major cosmetics companies soon follow suit.[20] | |

| 1980 | Ingrid Newkirk and Alex Pacheco found People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). | |

| 1981-1983 | The Silver Spring monkey controversy begins when Alex Pacheco's undercover investigation of Edward Taub's monkey research laboratory results in Taub's arrest for animal cruelty. Taub is later convicted on six counts of inadequate veterinary care, which is then overturned on the grounds that state animal welfare laws do not apply to federally-funded experiments.[21] | |

| 1984 | Tom Regan publishes The Case for Animal Rights, a highly influential philosophical argument that animals have rights (as opposed to Peter Singer's utilitarian case for animal liberation).[46] | |

| 1986 | Farm Sanctuary is founded as an American animal protection organization.[47][48][49] | |

| 1990 | PETA and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine end their highly publicized legal battle over the Silver Spring monkeys, failing to gain custody of the animals.[21] | |

| 1992 | Switzerland becomes the first country to include protections for animals in its constitution.[23] | |

| 1993 | The Great Ape Project is launched in London by Australian philosopher Peter Singer and Italian philosopher Paola Cavalieri. It is an international animal rights movement with the goal of extending rights to nonhuman primates.[50] | |

| 1997 | The European Union's Protocol on Animal Protection is annexed to the treaty establishing the European Community. The Protocol recognizes animals as "sentient beings" (rather than mere property) and requires countries to pay "full regard to the welfare requirements of animals" when making laws regarding their use.[23] | |

| 1998 | The EU passes the Council Directive 98/58/EC Concerning the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes, which is based on a revised Five Freedoms: freedom from hunger and thirst; from discomfort; from pain, injury, and disease; from fear and distress; and to express normal behavior.[23] | |

| 1999 | Willem van Eelen secures the first patent for in vitro meat.[17] | |

| 1999 | European Union Council Directive 1999/74/EC[51] is legislation passed by the European Union on the minimum standards for keeping egg laying hens which effectively bans conventional battery cages. | |

| 2000-2009 | Bans on fur farming are instituted in the United Kingdom, Austria, Netherlands, Switzerland, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[23][52] | |

| 2001 | The European Court of Justice issues a conservative interpretation of the 1997 Protocol on Animal Protection in the Jippes case, stating that the law did not create new protections for animals but only codified existing ones.[23] | |

| 2006 | Veal crates become illegal in the EU.[23] | |

| 2008 | Spain passes a non-legislative measure to grant non-human primates the right to life, liberty, and freedom from use in experiments. However, this requires further action by the government to become formal law, which has not been taken.[23] | |

| 2008 | California passes a ballot measure requiring that a chicken "be able to extend its limbs fully and turn around freely". This has been described as a ban on battery cages, but battery cages giving 116 square inches per hen are allowed under the law.[53][54] | |

| 2010 | Gary Yourofsky's YouTube lecture on veganism and factory farming entitled "Best Speech You Will Ever Hear" is translated into Hebrew, and goes viral in Israel. The speech helps drive a surge in Israeli interest in veganism and animal rights.[55][56] | |

| 2010 | EU Directive 2010/63/EU[57] is the EU legislation "on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes" and is one of the most stringent ethical and welfare standards worldwide.[58] | |

| 2011-2016 | After undercover investigations spark public outrage over animal abuse on industrial farms, several American states introduce "ag-gag" laws in an effort to criminalize such investigations.[59] | |

| 2012 | The EU's ban on battery cages goes into effect. Furnished cages are still allowed, however.[23] | |

| 2012 | A group of prominent scientists issue the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, which states that “the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.”[60] | |

| 2013 | The EU bans testing cosmetics on animals.[27] | |

| 2013 | The Nonhuman Rights Project files the first-ever lawsuits on behalf of chimpanzees, demanding courts grant them the right to bodily liberty via a writ of habeas corpus.[61] The petitions are denied and the cases move on to appellate courts.[62] | |

| 2013 | The UK legislation to protect animals in research, The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, is amended to protect "...all living vertebrates, other than man, and any living cephalopod." Previously, the only protected invertebrate was the common octopus. | United Kingdom |

| 2014 | India becomes the first country in Asia to ban testing cosmetics on animals as well as imports of animal-tested cosmetics.[63] | |

| 2015 | In a survey of Israelis, 8% of respondents identify as vegetarian and 5% as vegan (up from 2.5% vegetarians in 2010),[64] making Israel the country with the highest percentage of vegans.[65] | |

| 2015-2016 | Following major public backlash prompted by the 2013 film Blackfish, SeaWorld announces it will end its controversial orca shows and breeding program.[66] | |

| 2015-2016 | In the U.S., a number of major egg buyers and producers switch from battery-cage to cage-free eggs.[67][68][69] | |

| 2016 | Cellular agriculture company Memphis Meats announces the creation of the first in vitro meatball.[26] |

Numerical and visual data

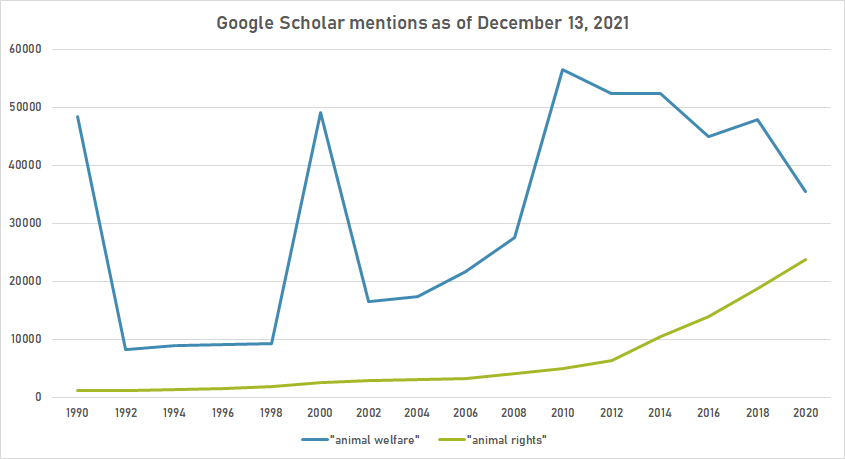

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 13, 2021.

| Year | "animal welfare" | "animal rights" |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 48,300 | 1,190 |

| 1992 | 8,260 | 1,170 |

| 1994 | 8,930 | 1,330 |

| 1996 | 9,130 | 1,510 |

| 1998 | 9,230 | 1,870 |

| 2000 | 49,100 | 2,490 |

| 2002 | 16,400 | 2,940 |

| 2004 | 17,300 | 3,030 |

| 2006 | 21,700 | 3,160 |

| 2008 | 27,600 | 3,990 |

| 2010 | 56,400 | 4,970 |

| 2012 | 52,300 | 6,380 |

| 2014 | 52,300 | 10,500 |

| 2016 | 45,000 | 13,900 |

| 2018 | 47,900 | 18,800 |

| 2020 | 35,400 | 23,800 |

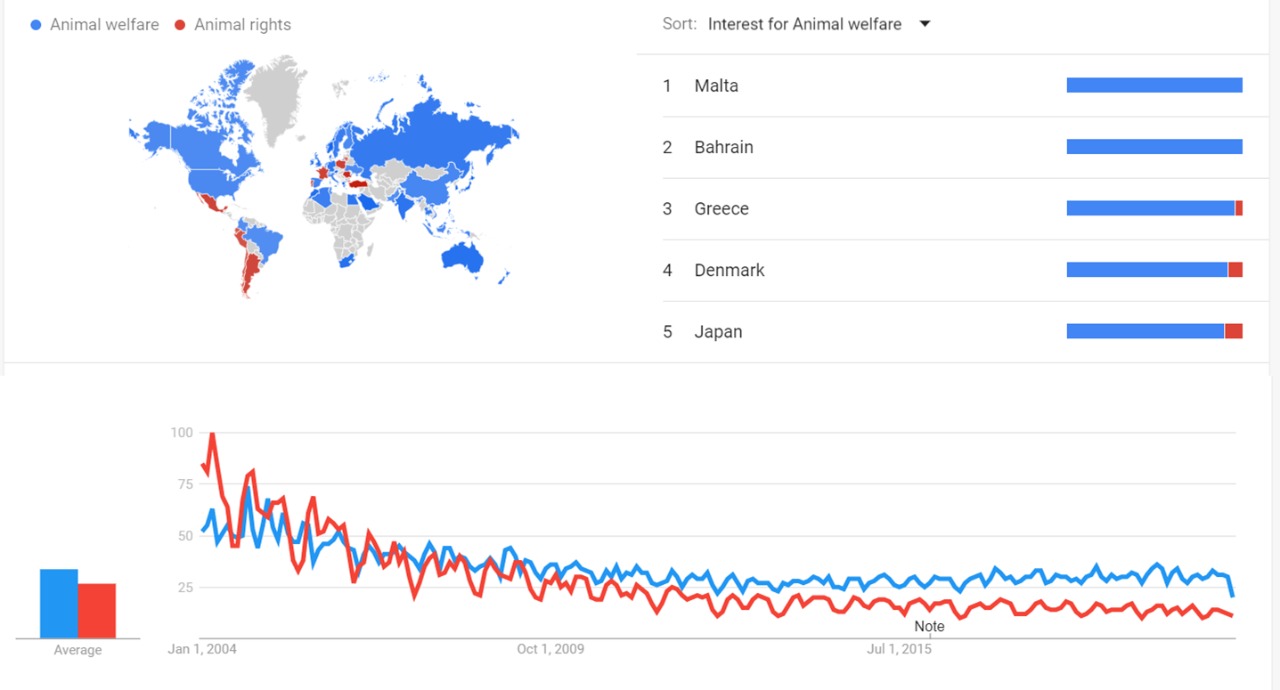

Google trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Animal welfare (topic) and Animal rights (topic).[70]

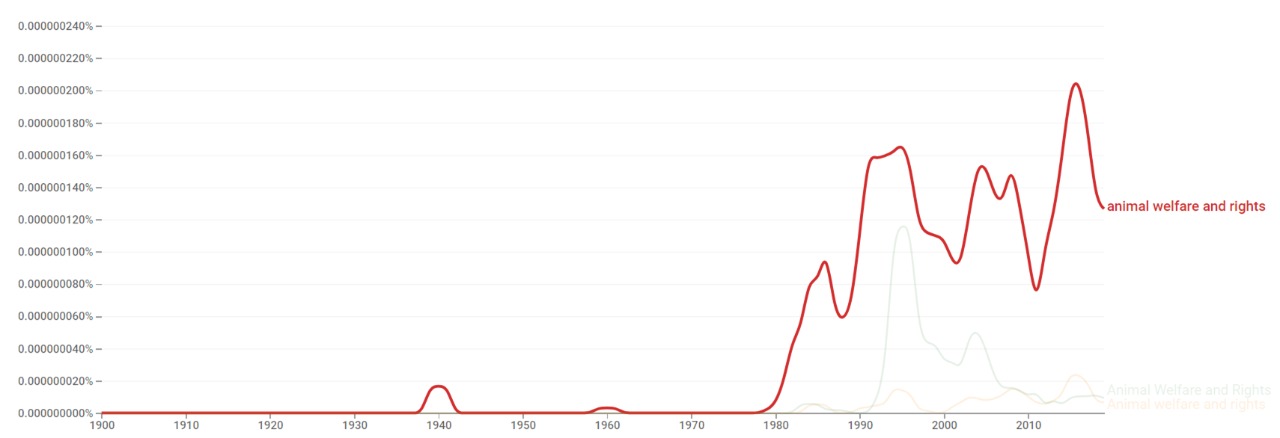

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Animal welfare and rights from 1900 to 2019.[71]

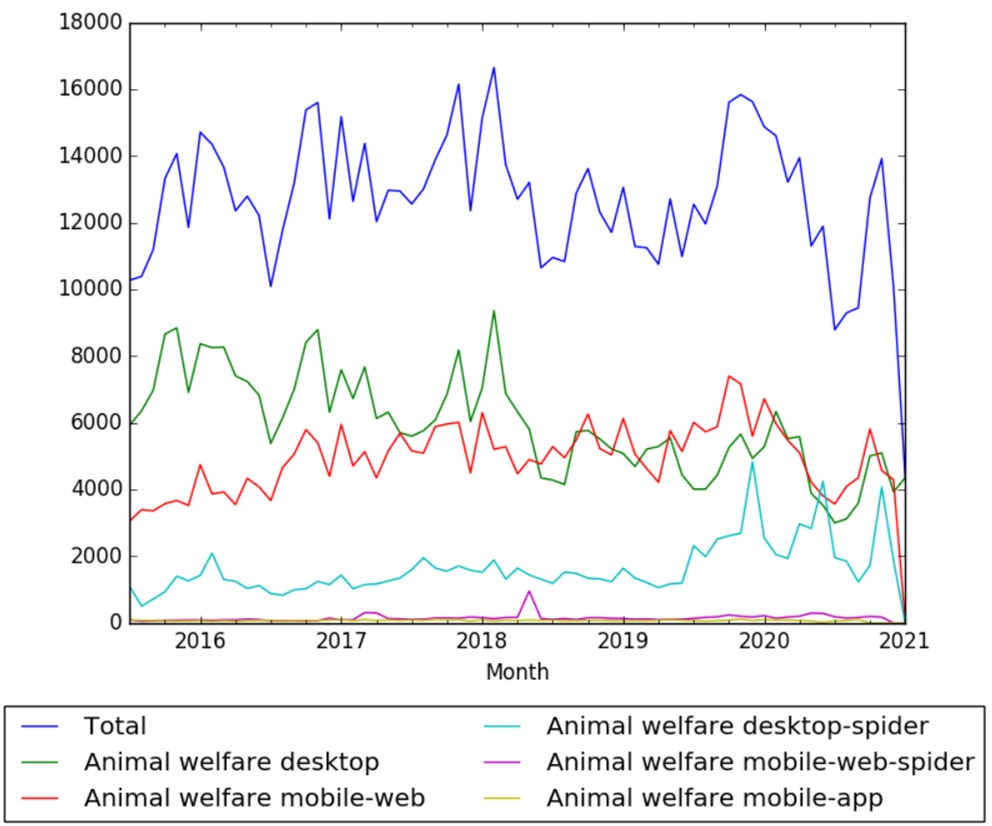

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Animal welfare , on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.[72]

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Animal rights , on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.[73]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by FIXME.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- Animal Liberation. Save all animals. Facebook group

- Union of Animal Defenders Facebook group

- Petitions For Animal Welfare/Rights Facebook group

- Animal Rights and the Environment Facebook group

- Animal lovers Facebook group

- ANIMAL RIGHTS WORLDWIDE Facebook group

- Global Veganism ~ Animal Rights and Environmental Activism. Facebook group

- Vegan Awakening Facebook group

- Vegan Planet For The Animals 🐮🐷 Facebook group

- Austin Vegans Facebook group

- Vegan Buddhism Facebook group

- Vegan Copenhagen Facebook group

- WORLDWIDE VEGANS AND ANIMAL-HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP Facebook group

- Vegan Colorado Facebook group

- Animal Rights Strategy Group Facebook group

- Animal Rights Strategy Group (Original) Facebook group

- Muslim Vegans Facebook group

- Intermittent Fasting for Vegans Facebook group

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

- Timeline of animal welfare and rights in the United States

- Timeline of animal welfare and rights in Europe

- Timeline of vegetarianism and veganism

- Animal welfare in the United States

- Animal welfare and rights in China

- Animal welfare and rights in India

- Abolitionism (animal rights)

- Universal Declaration on Animal Welfare

- History of vegetarianism

- Timeline of cellular agriculture

- Speciesism

- Timeline of wild animal suffering

External links

References

- ↑ "History of Animal Domestication". March 11, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ E. Szűcs; R Geers; E. N. Sossidou; D. M. Broom (November 2012). "Animal Welfare in Different Human Cultures, Traditions and Religious Faiths". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Science. 25 (11): 1499–1506. PMC 4093044

. PMID 25049508. doi:10.5713/ajas.2012.r.02.

. PMID 25049508. doi:10.5713/ajas.2012.r.02.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nathan Morgan. "The Hidden History of Greco-Roman Vegetarianism". Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Richard R. Sharp. "Ethical Issues in the Use of Animals in Biomedical Research". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Zenjiro Watanabe. "Removal of the Ban on Meat" (PDF). Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Animal Consciousness". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Raymond Giraud. "Rousseau and Voltaire: The Enlightenment and Animal Rights". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jeremy Bentham. "An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation" (PDF). Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Belden C. Lane. "Ravished by Beauty: The Surprising Legacy of Reformed Spirituality". Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "History of the Movement" (PDF). Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "A History of Antivivisection from the 1800s to the Present: Part 1 (mid-1800s to 1914)". Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedwatanbe - ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jonathan Safran Foer (2009). Eating Animals. Little, Brown and Company.

- ↑ "A History of Antivivisection from 1800s to Present: Part 2 (1914-1970)". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Animal Rights Movement" (PDF). Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Benjamin Adams; Jean Larson. "Legislative History of the Animal Welfare Act: Introduction". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Zuhaib Fayaz Bhat; Hina Fayaz (April 2011). "Prospectus of cultured meat—advancing meat alternatives". Journal of Food Science Technology. 48 (2). PMC 3551074

.

.

- ↑ "Meat and Animal Feed". Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Peter Singer". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Henry Spira (1985). "Fighting to Win". In Peter Singer. In Defense of Animals. Basil Blackwell. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Peter Carlson (February 24, 1991). "The Great Silver Spring Monkey Debate". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Vivian Kuo; Martin Savidge (February 9, 2014). "Months after 'Blackfish' airs, debate over orcas continues". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 Nicholas K. Pedersen. "Detailed Discussion of European Animal Welfare Laws 2003 to Present: Explaining the Downturn". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Will Potter (2011). Green is the New Red: An Insider's Account of a Social Movement Under Siege. City Lights Publishers.

- ↑ Henry Fountain (August 5, 2013). "A Lab-Grown Burger Gets a Taste Test". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hilary Hanson (February 2, 2016). "'World's First' Lab-Grown Meatball Looks Pretty Damn Tasty". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Rebecca Rifkin (May 18, 2015). "In U.S., More Say Animals Should Have Same Rights as People". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Vegan Diets Become More Popular, More Mainstream". CBS News. January 5, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ Daphne Rousseau (October 22, 2014). "Israel, the promised land for vegans". The Times of Israel. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Global Polls Reveal Consumers Worldwide Want an End to Animal Testing for Cosmetics". January 27, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ Ven. S. Dhammika. "The Edicts of King Asoka" (PDF). Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Vivisection - An Ancient History". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Animal Welfare". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Hannah Renier. "An Early Vegan: Lewis Gompertz". London Historians. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "History of Vegetarianism: Origins of Some Words". Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ R. B. Freeman. "On the Origin of Species". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ "The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960". Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Steven Best (ed.) (2004). Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?. Lantern Books.

- ↑ Amy Mosel. "What About Wilbur? Proposing a Federal Statute to Provide Minimum Humane Living Conditions for Farm Animals Raised for Food Production". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Richard D. Ryder. "Speciesism Again: the original leaflet" (PDF). Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Joanne Zurlo; Deborah Rudacille; Alan M. Goldberg. "Animals and Alternatives in Testing: History, Science, and Ethics". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Rats, Mice & Birds". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "US Domestic Terrorism: Animal Liberation Front". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Animal Rights International: A Historical Note and Tribute to Henry Spira". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Barnaby Feder. "Henry Spira, 71, Animal Rights Crusader". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Lawrence Finsen; Susan Finsen (1994). The Animal Rights Movement in America: From Compassion to Respect. Twayne Publishers.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedThe_Longest_Struggle:_Animal_Advocacy_from_Pythagoras_to_PETA - ↑ "About Farm Sanctuary". farmsanctuary.org. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ DeMello, Margo. Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-animal Studies.

- ↑ Bekoff, Marc. Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare, 2nd Edition [2 volumes]: Second Edition.

- ↑ "European Union Council Directive 1999/74/EC". Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ Cecilia Mille; Eva Frejadotter Diesen; Niki Woods (translator). "The best animal welfare in the world? An investigation into the myth about Sweden" (PDF). Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ "California Proposition 2, Standards for Confining Farm Animals (2008)". Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Bradley Miller (February 10, 2015). "Flawed ballot measure is coming home to roost". Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Erica Chernofsky (January 25, 2016). "Israeli veganism takes root in land of milk and honey". Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ Sarah Toth Stub (February 16, 2016). "Life After Brisket". Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council". Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ↑ "EuroScience supports Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes". EuroScience. 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ↑ Alicia Prygoski (2015). "Detailed Discussion of Ag-gag Laws". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ "The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness" (PDF). Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ "First-Ever Lawsuits Filed on Behalf of Captive Chimpanzees". Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Michael Mountain (December 10, 2013). "New York Cases – Judges' Decisions and Next Steps". Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ↑ Melissa Cronin (October 14, 2014). "This is the First Country in Asia to Ban All Cosmetics Tested on Animals". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ Tova Cohen (July 21, 2015). "In the land of milk and honey, Israelis turn vegan". Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ Ben Sales (October 15, 2014). "Israelis growing hungry for vegan diet". Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ↑ Brian Clark Howard (March 17, 2016). "SeaWorld to End Controversial Orca Shows and Breeding".

- ↑ Eliza Barclay (December 30, 2015). "The Year In Eggs: Everyone's Going Cage-Free, Except Supermarkets". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ Dan Charles (January 15, 2016). "Most U.S. Egg Producers Are Now Choosing Cage-Free Houses". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ John Kell (April 5, 2016). "Walmart Is the Latest Retailer to Make a Cage-Free Egg Vow". Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Animal welfare and Animal rights". trends.google.com. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "Animal welfare and rights". books.google.com. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ "Animal welfare". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Animal rights". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.