Difference between revisions of "Timeline of sanitation"

| (37 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This is a '''timeline of {{w|sanitation}}''', attempting to describe events covering {{w|sewage}} systems as well as sanitation facilities such as {{w|sewage}} and {{w|toilets}}. {{w|Toilet paper}} is described in the [[timeline of hygiene]]. | + | This is a '''timeline of {{w|sanitation}}''', attempting to describe events covering {{w|sewage}} systems as well as sanitation facilities such as {{w|sewage}} and {{w|toilets}}. {{w|Toilet paper}} is described in the [[timeline of hygiene]]. Historical events related to the timeline can be found in the [[timeline of hygiene]], [[timeline of water supply]], [[timeline of water treatment]] and [[timeline of pipeline transport]]. |

==Big picture== | ==Big picture== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| 1600s–1700s || Rapid expansion of waterworks and pumping systems take place in {{w|Europe}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> | | 1600s–1700s || Rapid expansion of waterworks and pumping systems take place in {{w|Europe}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1800s || | + | | 1800s || Sewer systems begin implementation in many European and US cities, initially discharging untreated sewage to waterways. When discharge of untreated sewerage become increasingly unacceptable, experimentation towards improved treatment methods would result in sewage farming, chemical precipitation, filtration, sedimentation, chemical treatment, and activated sludge treatment using aerobic microorganisms.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> {{w|Earth closets}} are popular during this time.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> Around 1850 onwards, modern sewerage is “reborn”, but many of the principles grasped by the ancients are still in use today.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> Indoor plumbing initiates in Europe and the United States.<ref name="History of Plumbing Systems"/> Late in the century, many cities start constructing extensive sewer systems to help control outbreaks of disease such as {{w|typhoid}} and {{w|cholera}}. Also, some cities begin to add chemical treatment and sedimentation systems to their sewers.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> {{w|Flush toilet}}s come into widespread use late in the century as well.<ref>''[http://www.amazon.com/dp/193259521X Poop Culture: How America is Shaped by its Grossest National Product]'', Dave Praeger</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| 1900s || Most cities in the {{w|Western world}} add more expensive systems for sewage treatment.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> | | 1900s || Most cities in the {{w|Western world}} add more expensive systems for sewage treatment.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Recent years || Worldwide, about 2,4 billion people lack sanitation, such as | + | | Recent years || Worldwide, about 2,4 billion people are estimated to lack sanitation, such as {{w|toilet}}s or {{w|latrine}}s. Every year, 5 million people die of waterborne diseases, including nearly 1,000 children dying every day due to preventable water and sanitation-related diarrhoeal diseases.<ref name="Waterborne diseases">{{cite web|title=Waterborne diseases|url=http://www.lenntech.com/processes/disinfection/deseases/waterborne-diseases-contagion.htm|website=lenntech.com|accessdate=8 August 2017}}</ref> At least 1,8 billion people globally use a source of drinking water that is fecally contaminated. More than 80% of wastewater resulting from human activities is discharged into rivers or sea without any pollution removal.<ref name="Goal 6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all">{{cite web|title=Goal 6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all|url=http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/|website=un.org|accessdate=8 August 2017}}</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| − | ! Year !! | + | ! Year !! Category !! Details !! Country/location |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 4000 BC || || The {{w|Babylon}}ians introduce clay sewer pipes, with the earliest examples found in the Temple of Bel at {{w|Nippur}} and at {{w|Eshnunna}}, {{w|Babylonia}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY">{{cite book|last1=Burke|first1=Joseph|title=FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=fdIoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq=The+Babylonians+introduced+the+world+to+clay+sewer+pipes,+c4000+BCE,+with+the+earliest+examples+found+in+the+Temple+of+Bel+at+Nippur+and+at+Eshnunna,+Babylonia.&source=bl&ots=_2hJfLI0CM&sig=qaUlAtBRoGK5pMfwQ_YJ2MF_-VI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwil_NqSyrzVAhWDGZAKHfmlALIQ6AEIJjAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Babylonians%20introduced%20the%20world%20to%20clay%20sewer%20pipes%2C%20c4000%20BCE%2C%20with%20the%20earliest%20examples%20found%20in%20the%20Temple%20of%20Bel%20at%20Nippur%20and%20at%20Eshnunna%2C%20Babylonia.&f=false|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || | + | | 4000 BC || Technology || The {{w|Babylon}}ians introduce clay sewer pipes, with the earliest examples found in the Temple of Bel at {{w|Nippur}} and at {{w|Eshnunna}}, {{w|Babylonia}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY">{{cite book|last1=Burke|first1=Joseph|title=FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=fdIoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq=The+Babylonians+introduced+the+world+to+clay+sewer+pipes,+c4000+BCE,+with+the+earliest+examples+found+in+the+Temple+of+Bel+at+Nippur+and+at+Eshnunna,+Babylonia.&source=bl&ots=_2hJfLI0CM&sig=qaUlAtBRoGK5pMfwQ_YJ2MF_-VI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwil_NqSyrzVAhWDGZAKHfmlALIQ6AEIJjAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Babylonians%20introduced%20the%20world%20to%20clay%20sewer%20pipes%2C%20c4000%20BCE%2C%20with%20the%20earliest%20examples%20found%20in%20the%20Temple%20of%20Bel%20at%20Nippur%20and%20at%20Eshnunna%2C%20Babylonia.&f=false|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 4000 BC–2500 BC || || Evidence of surface-based storm drainage systems in early [[w:Babylonian empire|Babylonian]] and {{w|Mesopotamian Empire}}s in Iraq is found.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide">{{cite journal|last1=De Feo|first1=Giovanni|last2=Antoniou|first2=George|last3=Fardin|first3=Hilal Franz|last4=El-Gohary|first4=Fatma|last5=Zheng|first5=Xiao Yun|last6=Reklaityte|first6=Ieva|last7=Butler|first7=David|last8=Yannopoulos|first8=Stavros|last9=Angelakis|first9=Andreas N.|title=The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide|doi=10.3390/su6063936|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263278132_The_Historical_Development_of_Sewers_Worldwide|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Iraq}} | + | | 4000 BC–2500 BC || Technology || Evidence of surface-based storm drainage systems in early [[w:Babylonian empire|Babylonian]] and {{w|Mesopotamian Empire}}s in Iraq is found.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide">{{cite journal|last1=De Feo|first1=Giovanni|last2=Antoniou|first2=George|last3=Fardin|first3=Hilal Franz|last4=El-Gohary|first4=Fatma|last5=Zheng|first5=Xiao Yun|last6=Reklaityte|first6=Ieva|last7=Butler|first7=David|last8=Yannopoulos|first8=Stavros|last9=Angelakis|first9=Andreas N.|title=The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide|doi=10.3390/su6063936|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263278132_The_Historical_Development_of_Sewers_Worldwide|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Iraq}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 3500 BC || || The making of alloy begins.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice"/> || | + | | 3500 BC || Technology || The making of {{w|alloy}} begins.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 3200 BC–2300 BC || || In the early {{w|Minoan civilization}}, issues related to sanitary techniques are considered of great importance. Advanced wastewater and stormwater management are practiced. In several Minoan palaces, one of the most important elements is the provision and distribution of water and the removal of waste and stormwater by means of sophisticated hydraulic works. The sewage and drainage systems are mainly stone structures. Stone conduits forme drains which lead rainwater from the courts outside the palaces, to eliminate the risk of flooding.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|Greece}} | + | | 3200 BC–2300 BC || System || In the early {{w|Minoan civilization}}, issues related to sanitary techniques are considered of great importance. Advanced wastewater and stormwater management are practiced. In several Minoan palaces, one of the most important elements is the provision and distribution of water and the removal of waste and stormwater by means of sophisticated hydraulic works. The sewage and drainage systems are mainly stone structures. Stone conduits forme drains which lead rainwater from the courts outside the palaces, to eliminate the risk of flooding.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|Greece}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 3200 BC–2200 BC || || Early drainage systems are built in {{w|Skara Brae}}, {{w|Scotland}}. Stone huts have drains with cubicles over them, probably used as toilets.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 3200 BC–2200 BC || System || Early drainage systems are built in {{w|Skara Brae}}, {{w|Scotland}}. Stone huts have drains with cubicles over them, probably used as toilets.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 3000 BC–2700 BC || || The {{w|Indus Valley Civilization}} shows [[w:Sanitation in the Indus Valley Civilization|early evidence of public water supply and sanitation]], having developed flushing toilets, along with a working sewer system, to deal with the issues of waste disposal and indoor sanitation.<ref name="History of Plumbing Systems">{{cite web|title=History of Plumbing Systems|url=http://www.homeadvisor.com/r/history-of-plumbing/#.WYeNNlGkqUk|website=homeadvisor.com|accessdate=6 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="Jews, Church & Civilization, Volume I">{{cite book|last1=Birnbaum|first1=David|title=Jews, Church & Civilization, Volume I|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=WXbO9Gz_YbkC&pg=PA53&lpg=PA53&dq=%22plumbing%22+%22qin+dynasty%22&source=bl&ots=ZxSjuhpgnH&sig=V7kbf2IrQOeTI_YoT2Qs14vKpBw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjA8p-qwunVAhWFIZAKHdv9AmgQ6AEIWDAO#v=onepage&q=%22plumbing%22%20%22qin%20dynasty%22&f=false|accessdate=21 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|India}} | + | | 3000 BC–2700 BC || System || The {{w|Indus Valley Civilization}} shows [[w:Sanitation in the Indus Valley Civilization|early evidence of public water supply and sanitation]], having developed flushing toilets, along with a working sewer system, to deal with the issues of waste disposal and indoor sanitation.<ref name="History of Plumbing Systems">{{cite web|title=History of Plumbing Systems|url=http://www.homeadvisor.com/r/history-of-plumbing/#.WYeNNlGkqUk|website=homeadvisor.com|accessdate=6 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="Jews, Church & Civilization, Volume I">{{cite book|last1=Birnbaum|first1=David|title=Jews, Church & Civilization, Volume I|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=WXbO9Gz_YbkC&pg=PA53&lpg=PA53&dq=%22plumbing%22+%22qin+dynasty%22&source=bl&ots=ZxSjuhpgnH&sig=V7kbf2IrQOeTI_YoT2Qs14vKpBw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjA8p-qwunVAhWFIZAKHdv9AmgQ6AEIWDAO#v=onepage&q=%22plumbing%22%20%22qin%20dynasty%22&f=false|accessdate=21 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|India}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2600 BC – 1100 BC || || The ancient Greek civilization of Crete, known as the {{w|Minoan civilization}}, already uses underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || | + | | 2600 BC – 1100 BC || System || The ancient Greek civilization of Crete, known as the {{w|Minoan civilization}}, already uses underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2350 BC || || The Indus city of {{w|Lothal}} provides all houses with their own private toilet which is connected to a covered sewer network constructed of brickwork held together with a gypsum-based mortar that empties either into the surrounding water bodies or alternatively into {{w|cesspit}}s, the latter of which are regularly emptied and cleaned.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Khan|first1=Saifullah|title=1 Chapter 2 Sanitation and wastewater technologies in Harappa/Indus valley civilization ( ca . 2600-1900 BC)|url=http://www.academia.edu/5937322/Chapter_2_Sanitation_and_wastewater_technologies_in_Harappa_Indus_valley_civilization_ca._26001900_BC|website=Academia.edu|publisher=Academia.edu|accessdate=3 August 2017|ref=http://www.academia.edu/5937322/Chapter_2_Sanitation_and_wastewater_technologies_in_Harappa_Indus_valley_civilization_ca._26001900_BC}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Maya plumbing: First pressurized water feature found in New World|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/05/100504155421.htm|publisher=Penn State|accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="Ancient Indian Toilets">{{cite web|title=Ancient Indian Toilets|url=https://sites.google.com/a/brvgs.k12.va.us/wh-14-sem-1-ancient-india-ogm/invention-page-sample/toilets|website=google.com|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|India}} | + | | 2350 BC || System || The Indus city of {{w|Lothal}} provides all houses with their own private toilet which is connected to a covered sewer network constructed of brickwork held together with a gypsum-based mortar that empties either into the surrounding water bodies or alternatively into {{w|cesspit}}s, the latter of which are regularly emptied and cleaned.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Khan|first1=Saifullah|title=1 Chapter 2 Sanitation and wastewater technologies in Harappa/Indus valley civilization ( ca . 2600-1900 BC)|url=http://www.academia.edu/5937322/Chapter_2_Sanitation_and_wastewater_technologies_in_Harappa_Indus_valley_civilization_ca._26001900_BC|website=Academia.edu|publisher=Academia.edu|accessdate=3 August 2017|ref=http://www.academia.edu/5937322/Chapter_2_Sanitation_and_wastewater_technologies_in_Harappa_Indus_valley_civilization_ca._26001900_BC}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Maya plumbing: First pressurized water feature found in New World|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/05/100504155421.htm|publisher=Penn State|accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="Ancient Indian Toilets">{{cite web|title=Ancient Indian Toilets|url=https://sites.google.com/a/brvgs.k12.va.us/wh-14-sem-1-ancient-india-ogm/invention-page-sample/toilets|website=google.com|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|India}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2100 BC || || The [[w:Ancient egypt|Egyptian]] city if {{w|Herakopolis}} has a system of removal of wastes, organic and inorganic to locations outside the living and/or communal areas, usually to the rivers. Finer houses have bathrooms and toilet seats made of limestone. || {{w|Egypt}} | + | | 2100 BC || System || The [[w:Ancient egypt|Egyptian]] city if {{w|Herakopolis}} has a system of removal of wastes, organic and inorganic to locations outside the living and/or communal areas, usually to the rivers. Finer houses have bathrooms and toilet seats made of limestone. || {{w|Egypt}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2100 BC || || The cities on the island of {{w|Crete}} have trunk sewers connecting homes.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice">{{cite book|last1=Chandrappa|first1=Ramesha|last2=Bhusan Das|first2=Diganta|title=Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=8c4h3qshpJYC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=%22500+BC+%22+%22+municipal+dump%22+%22greece%22&source=bl&ots=r8nfQY1DuD&sig=_01OsTMVBtNdE5_eP9SykeXKtb0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjFoObqydDVAhVGg5AKHQf5Bi0Q6AEIKTAB#v=onepage&q=%22500%20BC%20%22%20%22%20municipal%20dump%22%20%22greece%22&f=false|accessdate=12 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Greece}} | + | | 2100 BC || System || The cities on the island of {{w|Crete}} have trunk sewers connecting homes.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice">{{cite book|last1=Chandrappa|first1=Ramesha|last2=Bhusan Das|first2=Diganta|title=Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=8c4h3qshpJYC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=%22500+BC+%22+%22+municipal+dump%22+%22greece%22&source=bl&ots=r8nfQY1DuD&sig=_01OsTMVBtNdE5_eP9SykeXKtb0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjFoObqydDVAhVGg5AKHQf5Bi0Q6AEIKTAB#v=onepage&q=%22500%20BC%20%22%20%22%20municipal%20dump%22%20%22greece%22&f=false|accessdate=12 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Greece}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 2000 BC || || Descriptions of of foul water purification by boiling and filtering are written in {{w|Sanskrit}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION">{{cite web|title=SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION|url=http://www.hygieneforhealth.org.au/public_sanitation.php|website=hygieneforhealth.org.au|accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref> || | + | | 2000 BC || Publication || Descriptions of of foul water purification by boiling and filtering are written in {{w|Sanskrit}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION">{{cite web|title=SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION|url=http://www.hygieneforhealth.org.au/public_sanitation.php|website=hygieneforhealth.org.au|accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1800 BC || || The {{w|Minoans}} on {{w|Crete}} and [[w:Ancient Thera|Thera]] have some toilets flushing with water.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)">{{cite web|title=The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)|url=http://toilet-guru.com/flush-history.php|website=toilet-guru.com|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Greece}} | + | | 1800 BC || Technology || The {{w|Minoans}} on {{w|Crete}} and [[w:Ancient Thera|Thera]] have some toilets flushing with water.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)">{{cite web|title=The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)|url=http://toilet-guru.com/flush-history.php|website=toilet-guru.com|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Greece}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1200 BC || || Rich Egyptians use a container with sand for toilet, which is emptied by slaves.<ref name="A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY">{{cite web|title=A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY|url=http://www.localhistories.org/toilettime.html|website=localhistories.org|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> ||{{w|Egypt}} | + | | 1200 BC || Technoloogy || Rich Egyptians use a container with sand for toilet, which is emptied by slaves.<ref name="A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY">{{cite web|title=A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY|url=http://www.localhistories.org/toilettime.html|website=localhistories.org|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> ||{{w|Egypt}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1200 BC || || | + | | 1200 BC || Material || New materials are introduced with the beginning of the {{w|Iron Age}}.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1200 BC–700 BC || || {{w|Hattusa}}, the capital of the hittite Empire, has public waste disposal plumbing around this epoch.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)"/> || {{w|Turkey}} | + | | 1200 BC–700 BC || System || {{w|Hattusa}}, the capital of the hittite Empire, has public waste disposal plumbing around this epoch.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)"/> || {{w|Turkey}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1046 – 256 BC || || During the {{w|Zhou Dynasty}} in ancient China, sewers exist in various cities such as [[w:Ancient Linzi|Linzi]].<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|China}} | + | | 1046 – 256 BC || System || During the {{w|Zhou Dynasty}} in ancient China, sewers exist in various cities such as [[w:Ancient Linzi|Linzi]].<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|China}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 900 BC–100 AD || || The [[w:Ancient greece|Greeks]] on the sacred island of {{w|Delos}} have large-scale public plumbing in addition to private latrines flushed by running water in this period.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)"/> || {{w|Greece}} | + | | 900 BC–100 AD || System || The [[w:Ancient greece|Greeks]] on the sacred island of {{w|Delos}} have large-scale public plumbing in addition to private latrines flushed by running water in this period.<ref name="The invention of the flush toilet (at least in England)"/> || {{w|Greece}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 800 BC–100 BC || || The {{w|Etruscan civilization}} has drainage channels on the sides of streets in its towns. The etruscan system is based both on the natural slope of the plateau and on an artificial modification. The Etruscan system is planned in order to avoid water runoff interacting with the two necropolis located between the urban area and the [[w:Reno (river)|river Reno]], where wastewater is usually discharged.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|Italy}} | + | | 800 BC–100 BC || System || The {{w|Etruscan civilization}} has drainage channels on the sides of streets in its towns. The etruscan system is based both on the natural slope of the plateau and on an artificial modification. The Etruscan system is planned in order to avoid water runoff interacting with the two necropolis located between the urban area and the [[w:Reno (river)|river Reno]], where wastewater is usually discharged.<ref name="The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide"/> || {{w|Italy}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 700 BC–400 AD || || The Romans develop a very advanced technology for sanitation, including baths with flowing water, and underground sewers and drains. The drains of Rome are intended primarily to carry away runoff from storms and to flush streets. The {{w|Cloaca Maxima}} sewage system, combines three functions: wastewater removal, rainwater removal and swamp drainage. The waste water removed by the city’s sewage system, some of which, like the {{w|Cloaca Maxima}}, is still in use today.<ref name="History of Plumbing Systems"/> The Romans worship {{w|Cloacina}}, the goddess who presides over the Cloaca Maxima ("Greatest Drain"), the main trunk of the system of sewers in [[w:Rome, Italy|Rome]].<ref name="Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia">{{cite book|last1=Angelakis|first1=Andreas N.|last2=Mays|first2=Larry W.|last3=Koutsoyiannis|first3=Demetris|last4=Mamassis|first4=Nikos|title=Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=WxXu83RxSNwC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=cloacina+cloaca&source=bl&ots=2p_g_D9O0K&sig=2KubXFv32ZEj8omXII6ReAzKyD8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwic053uob7VAhUIQZAKHS2FDwMQ6AEIjAEwEg#v=onepage&q=cloacina%20cloaca&f=false|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Italy}} | + | | 700 BC–400 AD || System || The Romans develop a very advanced technology for sanitation, including baths with flowing water, and underground sewers and drains. The drains of Rome are intended primarily to carry away runoff from storms and to flush streets. The {{w|Cloaca Maxima}} sewage system, combines three functions: wastewater removal, rainwater removal and swamp drainage. The waste water removed by the city’s sewage system, some of which, like the {{w|Cloaca Maxima}}, is still in use today.<ref name="History of Plumbing Systems"/> The Romans worship {{w|Cloacina}}, the goddess who presides over the Cloaca Maxima ("Greatest Drain"), the main trunk of the system of sewers in [[w:Rome, Italy|Rome]].<ref name="Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia">{{cite book|last1=Angelakis|first1=Andreas N.|last2=Mays|first2=Larry W.|last3=Koutsoyiannis|first3=Demetris|last4=Mamassis|first4=Nikos|title=Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=WxXu83RxSNwC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=cloacina+cloaca&source=bl&ots=2p_g_D9O0K&sig=2KubXFv32ZEj8omXII6ReAzKyD8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwic053uob7VAhUIQZAKHS2FDwMQ6AEIjAEwEg#v=onepage&q=cloacina%20cloaca&f=false|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Italy}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 206 BC–24 AD || || Latrine use dates back to the Western Han Dynasty. A found toilet with running water, a stone seat and an armrest dates bak from this time.<ref>{{cite web|title=Find flushes away British toilet assertion|url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/find-flushes-away-british-toilet-assertion/article25467422/%7b%7burl%7d%7d/?reqid=%257B%257Brequest_id%257D%257D|website=theglobeandmail.com|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=China claims invention of toilet|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/851957.stm|website=bbc.co.uk|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|China}} | + | | 206 BC–24 AD || Technology || Latrine use dates back to the Western Han Dynasty. A found toilet with running water, a stone seat and an armrest dates bak from this time.<ref>{{cite web|title=Find flushes away British toilet assertion|url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/find-flushes-away-british-toilet-assertion/article25467422/%7b%7burl%7d%7d/?reqid=%257B%257Brequest_id%257D%257D|website=theglobeandmail.com|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=China claims invention of toilet|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/851957.stm|website=bbc.co.uk|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|China}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 200 BC – 100 BC || || In {{w|China}} Yellow Emperor’s Treatise on Internal Medicine dictates that "it is more important to prevent illness than to cure the illness when it has arisen". Clean water is known to be important in disease prevention so wells are covered, devices are used to filter water and the Chhii Shih (“sanitary police”) removes all animal and human corpses from waterways and buries all bodies found on land.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|China}} | + | | 200 BC – 100 BC || System || In {{w|China}} Yellow Emperor’s Treatise on Internal Medicine dictates that "it is more important to prevent illness than to cure the illness when it has arisen". Clean water is known to be important in disease prevention so wells are covered, devices are used to filter water and the Chhii Shih (“sanitary police”) removes all animal and human corpses from waterways and buries all bodies found on land.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|China}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 46 BC – 400 AD || || Roman settlements in the United Kingdom have complex sewer networks sometimes constructed out of hollowed–out elm logs, which are shaped so that they butt together with the down–stream pipe providing a socket for the upstream pipe.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 46 BC – 400 AD || System || Roman settlements in the United Kingdom have complex sewer networks sometimes constructed out of hollowed–out elm logs, which are shaped so that they butt together with the down–stream pipe providing a socket for the upstream pipe.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 100 AD || || [[w:ancient rome|Roman]] sewers collect [[w:Rainwater harvesting|rainwater]] and {{w|sewage}}. There are public lavatories. <ref name="A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY"/> || {{w|Italy}} | + | | 100 AD || Technology || [[w:ancient rome|Roman]] sewers collect [[w:Rainwater harvesting|rainwater]] and {{w|sewage}}. There are public lavatories. <ref name="A TIMELINE OF TOILETS IN HISTORY"/> || {{w|Italy}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 250 – 900 AD || || The [[w:Maya civilization|Classic Mayans]] at {{w|Palenque}} | + | | 250 – 900 AD || Technology || The [[w:Maya civilization|Classic Mayans]] at {{w|Palenque}} have underground aqueducts and flush toilets.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|Mexico}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 315 AD || Statistics || There are 144 public latrines in {{w|Rome}}.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times">{{cite web|title=Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times|url=http://www.sewerhistory.org/photosgraphics/public-baths-and-latrines-from-ancient-and-modern-times/|website=sewerhistory.org|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Italy}} | | 315 AD || Statistics || There are 144 public latrines in {{w|Rome}}.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times">{{cite web|title=Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times|url=http://www.sewerhistory.org/photosgraphics/public-baths-and-latrines-from-ancient-and-modern-times/|website=sewerhistory.org|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Italy}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1100s || || At {{w|Portchester Castle}}, stone chutes leading to the sea are built by monks. When the tide goes in and out it flushes away the sewage.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Tucker|first1=Ruth A.|title=Katie Luther, First Lady of the Reformation: The Unconventional Life of Katharina von Bora|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=pcQLDgAAQBAJ&pg=PT48&lpg=PT48&dq=Portchester+Castle+monks+built+stone+chutes+leading+to+the+sea.+When+the+tide+went+in+and+out+it+flushed+away+the+sewage.%22&source=bl&ots=iyWT7mEjt6&sig=0FUbi8Ut_U2f4aH8ykydNSYTzAU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi3sMbwgO7VAhXLh5AKHf3pAn4Q6AEINzAG#v=onepage&q=Portchester%20Castle%20monks%20built%20stone%20chutes%20leading%20to%20the%20sea.%20When%20the%20tide%20went%20in%20and%20out%20it%20flushed%20away%20the%20sewage.%22&f=false|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1100s || Technology || At {{w|Portchester Castle}}, stone chutes leading to the sea are built by monks. When the tide goes in and out it flushes away the sewage.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Tucker|first1=Ruth A.|title=Katie Luther, First Lady of the Reformation: The Unconventional Life of Katharina von Bora|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=pcQLDgAAQBAJ&pg=PT48&lpg=PT48&dq=Portchester+Castle+monks+built+stone+chutes+leading+to+the+sea.+When+the+tide+went+in+and+out+it+flushed+away+the+sewage.%22&source=bl&ots=iyWT7mEjt6&sig=0FUbi8Ut_U2f4aH8ykydNSYTzAU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi3sMbwgO7VAhXLh5AKHf3pAn4Q6AEINzAG#v=onepage&q=Portchester%20Castle%20monks%20built%20stone%20chutes%20leading%20to%20the%20sea.%20When%20the%20tide%20went%20in%20and%20out%20it%20flushed%20away%20the%20sewage.%22&f=false|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1200 || || In medieval Europe, Toilets in castles consist usually in vertical shafts cut into the thickness of the walls with a stone seat on top.<ref>{{cite web|title=Bathroom Toilet History|url=https://bathrooms.co.za/bathroom-toilet-history/|website=bathrooms.co.za|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Europe}} | + | | 1200 || Technology || In medieval Europe, Toilets in castles consist usually in vertical shafts cut into the thickness of the walls with a stone seat on top.<ref>{{cite web|title=Bathroom Toilet History|url=https://bathrooms.co.za/bathroom-toilet-history/|website=bathrooms.co.za|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Europe}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1370 || || The first closed sewer constructed in {{w|Paris}} is designed by Hughes Aubird on Rue Montmartre, and is 300 meters long.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|France}} | + | | 1370 || Facility || The first closed sewer constructed in {{w|Paris}} is designed by Hughes Aubird on Rue Montmartre, and is 300 meters long.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1388 || || The English Parliament bans dumping of waste in ditches and public waterways.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1388 || Policy || The English Parliament bans dumping of waste in ditches and public waterways.<ref name="Solid Waste Management: Principles and Practice"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1427 || || The first English public Act about sewerage issue is delivered.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1427 || Policy || The first English public Act about sewerage issue is delivered.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1530 || Policy || Decree issued in Paris requires that each new house must be equipped with a cesspool. Wastewater disposal in Paris starts being regulated.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | | 1530 || Policy || Decree issued in Paris requires that each new house must be equipped with a cesspool. Wastewater disposal in Paris starts being regulated.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1531 || || {{w|Sewage farm}}s (wastewater used for irrigation and fertilizing agricultural land) are operated in [[w:Bolesławiec|Bunzlau]], {{w|Silesia}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || | + | | 1531 || Facility || {{w|Sewage farm}}s (wastewater used for irrigation and fertilizing agricultural land) are operated in [[w:Bolesławiec|Bunzlau]], {{w|Silesia}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1596 || || Sir John Harington invents a flush toilet for his godmother {{w|Queen Elizabeth I}}, that releases wastes into cesspools.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1596 || Technology || Sir John Harington invents a {{w|flush toilet}} for his godmother {{w|Queen Elizabeth I}}, that releases wastes into cesspools.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| 1600s – 1700s || || Japanese cities collect {{w|human waste}} for use as crop {{w|fertilizer}}. This practice minimizes human contact with waste. {{w|Sewage}} is not discharged to rivers so pollution of waterways is minimized.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|Japan}} | | 1600s – 1700s || || Japanese cities collect {{w|human waste}} for use as crop {{w|fertilizer}}. This practice minimizes human contact with waste. {{w|Sewage}} is not discharged to rivers so pollution of waterways is minimized.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|Japan}} | ||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

| 1636 || Statistics || Report mentions 24 sewers in Paris, of which only 6 are covered, and every of them is clogged or ruined.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | | 1636 || Statistics || Report mentions 24 sewers in Paris, of which only 6 are covered, and every of them is clogged or ruined.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1650 || || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w|Edinburgh}}, {{w|Scotland}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1650 || Facility || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w|Edinburgh}}, {{w|Scotland}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1676 (9 October) || || Using the newly invented {{w|microscope}}, Dutch scientist {{w|Antonie van Leeuwenhoek}} reports the discovery of {{w|microorganism}}s. With the microscope, for the first time, small material particles that were suspended in the water can be seen, laying the groundwork for the future understanding of waterborne pathogens and {{w|waterborne diseases}}.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.historyofwaterfilters.com/microscope-in-water.html|title=The Use of the Microscope in Water Filter History|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref><ref name=Wootton>{{cite book |author=Wootton, David |title=Bad medicine: doctors doing harm since Hippocrates |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford [Oxfordshire] |year=2006 |pages=110|isbn=0-19-280355-7 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Netherlands}} | + | | 1676 (9 October) || Scientific development || Using the newly invented {{w|microscope}}, Dutch scientist {{w|Antonie van Leeuwenhoek}} reports the discovery of {{w|microorganism}}s. With the microscope, for the first time, small material particles that were suspended in the water can be seen, laying the groundwork for the future understanding of waterborne pathogens and {{w|waterborne diseases}}.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.historyofwaterfilters.com/microscope-in-water.html|title=The Use of the Microscope in Water Filter History|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref><ref name=Wootton>{{cite book |author=Wootton, David |title=Bad medicine: doctors doing harm since Hippocrates |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford [Oxfordshire] |year=2006 |pages=110|isbn=0-19-280355-7 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Netherlands}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1721 || || New decree issued in {{w|Paris}} requires property owners to pay for the cleaning of the covered sewers beneath their buildings.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | + | | 1721 || Policy || New decree issued in {{w|Paris}} requires property owners to pay for the cleaning of the covered sewers beneath their buildings.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1775 || || Scottish inventor {{w|Alexander Cumming}} is granted a patent for a flushing lavatory.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS">{{cite web|title=A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS|url=http://www.localhistories.org/toilets.html|website=localhistories.org|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1775 || Technology || Scottish inventor {{w|Alexander Cumming}} is granted a patent for a flushing lavatory.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS">{{cite web|title=A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS|url=http://www.localhistories.org/toilets.html|website=localhistories.org|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1778 || || English inventor {{w|Joseph Brahmah}} designs an improved flushing lavatory.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/><ref name="The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage">{{cite book|last1=Benidickson|first1=Jamie|title=The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=_v0WjdM6sLoC&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=%22Joseph+Bramah%22+%221778%22+%22flushing%22&source=bl&ots=GmzBmjJlF-&sig=1QjSdCYi4SXb_A6bo6WAygrQiWg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiokMLzxcPVAhWIHJAKHYljBZ4Q6AEIUjAG#v=onepage&q=%22Joseph%20Bramah%22%20%221778%22%20%22flushing%22&f=false|accessdate=6 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | + | | 1778 || Technology || English inventor {{w|Joseph Brahmah}} designs an improved flushing lavatory.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/><ref name="The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage">{{cite book|last1=Benidickson|first1=Jamie|title=The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage|url=https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=_v0WjdM6sLoC&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=%22Joseph+Bramah%22+%221778%22+%22flushing%22&source=bl&ots=GmzBmjJlF-&sig=1QjSdCYi4SXb_A6bo6WAygrQiWg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiokMLzxcPVAhWIHJAKHYljBZ4Q6AEIUjAG#v=onepage&q=%22Joseph%20Bramah%22%20%221778%22%20%22flushing%22&f=false|accessdate=6 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1789 || || {{w|Paris}} has about 26 km of sewers, and reservoirs are used to flush away the wastes blocked in the sewers.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} | + | | 1789 || System || {{w|Paris}} has about 26 km of sewers, and reservoirs are used to flush away the wastes blocked in the sewers.<ref name="Public baths and latrines from ancient and modern times"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1833 || || The {{w|water closet}} is first patented in the {{w|United States}}.<ref name="The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage"/> || {{w|United States}} | + | | 1833 || Technology || The {{w|water closet}} is first patented in the {{w|United States}}.<ref name="The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1840s || || Indoor {{w|plumbing}} is introduced, mixing human waste with water and flushing it away, eliminating the need for cesspools.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || | + | | 1840s || Technology || Indoor {{w|plumbing}} is introduced, mixing human waste with water and flushing it away, eliminating the need for cesspools.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| 1842 || Publication || British social reformer {{w|Edwin Chadwick}} publishes his ''Report on an inquiry into the sanitary condition of the labouring population of Great Britain'', in which he early notes scientifically that lack of sanitation leads to disease.<ref name="Sanitation and Health Mara"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | | 1842 || Publication || British social reformer {{w|Edwin Chadwick}} publishes his ''Report on an inquiry into the sanitary condition of the labouring population of Great Britain'', in which he early notes scientifically that lack of sanitation leads to disease.<ref name="Sanitation and Health Mara"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1852 || Facility || The first modern public lavatory, with flushing toilets, opens in {{w|London}}.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1854 || Scientific development || English physician Dr {{w|John Snow}} shows that {{w|cholera}} is spread by {{w|water}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1855–1860 || System || The first sewer systems in the United States are built in {{w|Chicago}} and {{w|Brooklyn}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1860 || Technology || Frenchman Jean Mouras is credited for the invention of the {{w|septic tank}} system, after having built a prototype fabricated from concrete with piping constructed of clay leading from Mouras home to the septic tank located in his yard. After several years of use, the system becomes successful. In 1881 Mouras would be granted a patent.<ref name="History of the Septic Tank System">{{cite web|title=History of the Septic Tank System|url=https://www.newtechbio.com/articles/history_of_the_septic_system.htm|website=newtechbio.com|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1868 || Facility || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w|Paris}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|France}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1868 || || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w| | + | | 1868 || Facility || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w|Berlin}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|Germany}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1868 || || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in {{w| | + | | 1868 || Facility || {{w|Sewage farm}}s are operated in different parts of the {{w|United States}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1870s–1920s || System || {{w|Victorian England}} implements the first–ever comprehensive urban system as a reaction to a series of cholera pandemics during this epoch.<ref name="Water History for our times">{{cite web|title=Water History for our times|url=http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002108/210879e.pdf|website=unesco.org|accessdate=3 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1877 || Scientific development || Agricultural chemist {{w|Jean Jacques Theophile Schloesing}} proves that {{w|nitrification}} is a biological process in the soil by using {{w|chloroform}} vapors to inhibit the production of {{w|nitrate}}. This knowledge would have one of its greatest practical applications in the treatment of {{w|sewerage}}.<ref name="Significant Events By Years">{{cite web|title=Significant Events By Years|url=https://www.asm.org/index.php/71-membership/archives/7852-significant-events-in-microbiology-since-1861#Year1861|website=asm.org|accessdate=8 April 2018}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1879 || || William Soper uses chlorinated lime to treat the sewage produced by typhoid patients.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || | + | | 1879 || Water treatment || William Soper uses chlorinated lime to treat the sewage produced by typhoid patients.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1883 || || The vacant/engaged bolt for public toilets is patented.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || | + | | 1883 || Technology || The vacant/engaged bolt for public toilets is patented.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1883 || || The {{w|septic tank}} is introduced in the United States.<ref name="History of the Septic Tank System"/> || {{w|United States}} | + | | 1883 || Introduction || The {{w|septic tank}} is introduced in the United States.<ref name="History of the Septic Tank System"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1884 || || The first pedestal toilet bowl is made.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || | + | | 1884 || Technology || The first pedestal toilet bowl is made.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | 1890 || || The first sewage treatment plant in the United States using [[w:Precipitation (chemistry)|chemical precipitation]] is built in {{w|Worcester, Massachusetts}}.<ref name="Metcalf 19142">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g5cJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=&f=false|title=American Sewerage Practice|last2=Eddy|first2=Harrison P.|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1914|isbn=|location=New York|page=|pages=|last1=Metcalf|first1=Leonard|authorlink=|accessdate=3 August 2017}} Vol. I: Design of Sewers.</ref>{{rp|2}}<ref name="Burian2">{{cite journal|last=Burian|first=Steven J.|last2=Nix|first2=Stephan J.|last3=Pitt|first3=Robert E.|last4=Durrans|first4=S. Rocky|year=2000|title=Urban Wastewater Management in the United States: Past, Present, and Future|url=http://www.sewerhistory.org/articles/whregion/urban_wwm_mgmt/urban_wwm_mgmt.pdf|journal=Journal of Urban Technology|location=London|publisher=Routledge|volume=7|issue=3|doi=10.1080/713684134}}</ref> || {{w|United States}} | + | | 1890 || Facility || The first sewage treatment plant in the United States using [[w:Precipitation (chemistry)|chemical precipitation]] is built in {{w|Worcester, Massachusetts}}.<ref name="Metcalf 19142">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g5cJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=&f=false|title=American Sewerage Practice|last2=Eddy|first2=Harrison P.|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1914|isbn=|location=New York|page=|pages=|last1=Metcalf|first1=Leonard|authorlink=|accessdate=3 August 2017}} Vol. I: Design of Sewers.</ref>{{rp|2}}<ref name="Burian2">{{cite journal|last=Burian|first=Steven J.|last2=Nix|first2=Stephan J.|last3=Pitt|first3=Robert E.|last4=Durrans|first4=S. Rocky|year=2000|title=Urban Wastewater Management in the United States: Past, Present, and Future|url=http://www.sewerhistory.org/articles/whregion/urban_wwm_mgmt/urban_wwm_mgmt.pdf|journal=Journal of Urban Technology|location=London|publisher=Routledge|volume=7|issue=3|doi=10.1080/713684134}}</ref><ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1892 || Technology || English stage magician {{w|John Nevil Maskelyne}} invents the coin operated lock for toilets.<ref name="A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOILETS"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1894 || Water treatment || German chemist {{w|Moritz Traube}} formally proposes the addition of chloride of lime (calcium hypochlorite) to water to render it "germ–free".<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1897 || Facility || A large {{w|sewage farm}} is established in {{w|Melbourne}}.<ref name="SNAPSHOTS OF PUBLIC SANITATION"/> || {{w|Australia}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1906 || Technology || German engineer {{w|Karl Imhoff}} develops the concept of what later would be named {{w|Imhoff tank}}.<ref>Karl Imhoff: ''Berufserinnerungen eines Wasseringenieurs.'' In: Karl und Klaus R. Imhoff: ''Taschenbuch der Stadtentwässerung.'' Oldenbourg, München 2007, ISBN 978-3-8356-3094-9, S. 5. [http://books.google.de/books?id=CRdVJYHdAG8C&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5&dq=%22Berufserinnerungen+eines+Wasseringenieurs%22&source=bl&ots=PUSE3agyVu&sig=O5et8T8QzJH65OQTAA7h7oSTdig&hl=de&sa=X&ei=R4MgU6ucLMHUtAbploCQDA&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Berufserinnerungen%20eines%20Wasseringenieurs%22&f=false (online auf: ''books.google.de'')]</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1912 || Technology || Scientists at the {{w|University of Manchester}} discover the sewage treatment process of {{w|activated sludge}}.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1913–1916 || Technology || In {{w|Birmingham}}, chemists experiment with the biosolids in sewage sludge by bubbling air through wastewater and then letting the mixture settle; once solids had settled out, the water is purified. By 1916, this activated sludge process is put into operation in {{w|Worcester}}, {{w|England}}.<ref name="Water Supply and Distribution Timeline">{{cite web|title=Water Supply and Distribution Timeline|url=http://www.greatachievements.org/?id=3610|website=greatachievements.org|accessdate=8 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|United Kingdom}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1914 || Publication || Boston engineers Leonard Metcalf and Harrison P. Eddy publish ''American Sewerage Practice, Volume I: Design of Sewers'', which declares that working for "the best interests of the public health" is the key professional obligation of sanitary engineers. The book would become a standard reference in the field of sanitation for decades.<ref name="Water Supply and Distribution Timeline"/> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1923 || Facility || The world’s first large-scale activated sludge plant is built at [[w:Jones Island, Milwaukee|Jones Island]], on the shore of {{w|Lake Michigan}}.<ref name="Water Supply and Distribution Timeline"/> || {{w|United States}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1925 || || {{w|Mahatma Gandhi}} declares that "Sanitation is more important than independence".<ref name="Why Sanitation Business Is Good Business">{{cite web|title=Why Sanitation Business Is Good Business|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2013/01/28/why-the-sanitatio-business-is-good-business/#195382776171|website=forbes.com|accessdate=24 August 2017}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1981–1990 || Program || The [[w:International Drinking Water Decade, 1981–90|International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade]] is launched by the {{w|United Nations}} to bring attention and support for clean water and sanitation worldwide.<ref name="">{{cite web|title=International Decade for Clean Drinking Water, 1981-1990|url=http://www.gdrc.org/uem/water/decade_05-15/first-decade.html|website=gdrc.org|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="WATER AND SANITATION IN UNICEF 1946-1986">{{cite web|title=WATER AND SANITATION IN UNICEF 1946-1986|url=https://www.unicef.org/about/history/files/CF-HST-MON-1987-008-water-sanitation-1946-86-mono-VIII.pdf|website=unicef.org|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1990 || Publication || The {{w|WHO}}/{{w|UNICEF}} Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP) starts producing regular estimates of national, regional and global progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).<ref name="Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2017">{{cite web|title=Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2017|url=http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258617/1/9789241512893-eng.pdf?ua=1|website=who.int|accessdate=8 August 2017}}</ref> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1990–2015 || Statistics || The proportion of the population practising open defecation in {{w|Ethiopia}} decreases from 92% in 1990 to 29% in 2015.<ref name="Access to clean water and sanitation around the world – mapped">{{cite web|last1=Purvis|first1=Katherine|title=Access to clean water and sanitation around the world – mapped|url=https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/jul/01/global-access-clean-water-sanitation-mapped|website=theguardian.com|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Ethiopia}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || Statistics || 1229 million people worldwide practice {{w|open defecation}}.<ref name="Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2017">{{cite web|title=Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2017|url=http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258617/1/9789241512893-eng.pdf?ua=1|website=who.int|accessdate=8 August 2017}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2001 || Organization || The {{w|World Toilet Organization}} is founded as a global non-profit organization with the claimed commitment to improve toilet and sanitation conditions worldwide. Since its foundation with 15 members, the World Toilet Organization would grow to include 151 member organizations in 53 countries.<ref name="World Toilet Organization">{{cite web|title=World Toilet Organization|url=http://worldtoilet.org/who-we-are/our-story/|website=worldtoilet.org|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2007 || || Readers of the {{w|British Medical Journal}} vote {{w|sanitation}} as the most important medical milestone since 1840.<ref name="Sanitation and Health Mara"/> || {{w|United Kingdom}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 2008 || || Prime Minister of India, {{w|Manmohan Singh}}, quoting {{w|Mahatma Gandhi}}, declares that “sanitation is more important than independence”.<ref name="Sanitation and Health Mara">{{cite journal|last1=Mara|first1=Duncan|last2=Lane|first2=Jon|last3=Scott|first3=Beth|last4=Trouba|first4=David|title=Sanitation and Health|journal=PLoS Med|doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000363|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2981586/|accessdate=22 August 2017|pmc=2981586}}</ref> || {{w|India}} |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || Technology || A mobile robotic toilet is released. Meant for physically disabled people, the device approaches the person upon request. Once used, the toilet automatically rolls back to the station to clean itself. It includes a bidet and hair dryer function.<ref>{{cite web|title=Robotic toilet maintains personal hygiene as the sick attends nature’s call|url=http://www.designbuzz.com/robotic-toilet-maintains-personal-hygiene-as-the-sick-attends-nature-s-call/|website=designbuzz.com|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Automatic Nature Call: Mobile Robotic Toilet|url=http://walyou.com/blog/2010/10/29/mobile-robotic-toilet/|website=walyou.com|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 (28 July) || Policy || The {{w|Human Right to Water and Sanitation}} is recognized as a {{w|human right}} by the {{w|United Nations General Assembly}}.<ref name=HRWS>{{cite web|title=Resolution 64/292: The human right to water and sanitation|url=https://www.un.org/es/comun/docs/?symbol=A/RES/64/292&lang=E|website=United Nations|accessdate=8 July 2017|date=August 2010}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2013 || || The {{w|World Toilet Organization}} achieves a milestone in global sanitation movement when 122 countries co-sponsor a United Nations resolution tabled by the Singapore government to designate 19 November, World Toilet Day as an official {{w|United Nations Day}}. The same year, the World Toilet Organization is granted consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council.<ref name="World Toilet Organization"/><ref>{{cite web|title=What is World Toilet Day?|url=http://wtd.unwater.org/2017/|website=unwater.org|accessdate=23 August 2017}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2011 || Program || The {{w|Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation}} starts the “reinvent the toilet challenge” campaign.<ref name="Ensuring Sustainability of Non-Networked Sanitation Technologies: An Approach to Standardization">{{cite web|last1=Starkl|first1=Markus|last2=Brunner|first2=Norbert|last3=Feil|first3=Magdalena|last4=Hauser|first4=Andreas|title=Ensuring Sustainability of Non-Networked Sanitation Technologies: An Approach to Standardization|url=http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.5b00887|website=acs.org|accessdate=22 August 2017}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || Organization || Ecotact is launched as a {{w|Nairobi}}-based company that provides low-income communities with sanitation. For an affordable price, the business provides the public with an Ikotoilet and access to clean, safe and hygienic sanitation facilities—services. The Ikotoilet block also offers its surrounding to local businesses that provide services like hair cutting, shoe shining and money transfer.<ref name="Why Sanitation Business Is Good Business"/><ref>{{cite web|title=Ecotact's Ikotoilet concept -- Sustainable sanitation services in Kenya|url=https://www.globalhand.org/en/browse/social_entrepreneurship/all/document/29633|website=globalhand.org|accessdate=24 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Ecotact|url=http://acumen.org/investment/ecotact/|website=acumen.org|accessdate=24 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=There is a toilet…which is changing the world|url=http://www.ontheup.org.uk/index.php/2011/08/there-is-a-toilet-which-is-changing-the-world/|website=ontheup.org.uk|accessdate=24 August 2017}}</ref> || {{w|Kenya}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || Statistics || 280,000 deaths worldwide are estimated to be caused by inadequate sanitation.<ref name="Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries.">{{cite journal|last1=Prüss-Ustün|first1=A|last2=Bartram|first2=J|last3=Clasen|first3=T|last4=Colford|first4=JM Jr|last5=Cumming|first5=O|last6=Curtis|first6=V|last7=Bonjour|first7=S|last8=Dangour|first8=AD|last9=De France|first9=J|last10=Fewtrell|first10=L|last11=Freeman|first11=MC|last12=Gordon|first12=B|last13=Hunter|first13=PR|last14=Johnston|first14=RB|last15=Mathers|first15=C|last16=Mäusezahl|first16=D|last17=Medlicott|first17=K|last18=Neira|first18=M|last19=Stocks|first19=M|last20=Wolf|first20=J|last21=Cairncross|first21=S|title=Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries.|doi=10.1111/tmi.12329|pmid=24779548|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24779548|accessdate=28 September 2017|pmc=4255749}}</ref> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015 || Program || The {{w|Sustainable Development Goals}} are formulated, including targets on access to water supply and sanitation at a global level.<ref name="FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY"/> Worldwide, 892 million people practice {{w|open defecation}} (down from 1229 million in 2000).<ref name="Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2017"/> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015 || Technology || OriFuji is introduced as an {{w|automatic toilet paper dispenser}}. The device automatically cuts the toilet papers and folds them into a neat triangle shape, making it easier for the next person to pull and roll out the paper.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://laughingsquid.com/the-orifuji-toilet-paper-dispenser-automatically-folds-the-end-of-the-paper-into-a-triangle-with-each-pull/|title=The OriFuji Toilet Paper Dispenser Automatically Folds the End of the Paper Into a Triangle With Each Pull|publisher=}}</ref> || {{w|Japan}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015 || Statistics || About 32−36% of the global population is estimated to lack household-level access to safe water or hygienic toilets.<ref name="Ensuring Sustainability of Non-Networked Sanitation Technologies: An Approach to Standardization"/> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Numerical and visual data == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

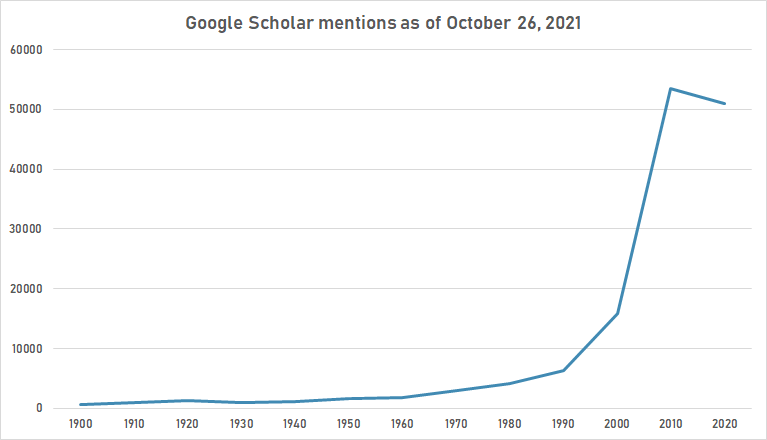

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 26, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! sanitation | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1900 || 600 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1910 || 884 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1920 || 1,250 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1930 || 905 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1940 || 1,090 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1950 || 1,560 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1960 || 1,830 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1970 || 3,000 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1980 || 4,080 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 1990 || 6,320 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 2000 || 15,800 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 2010 || 53,400 |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 2020 || 50,900 |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Sanitation gscho.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Gooogle Trends === | ||

| + | |||

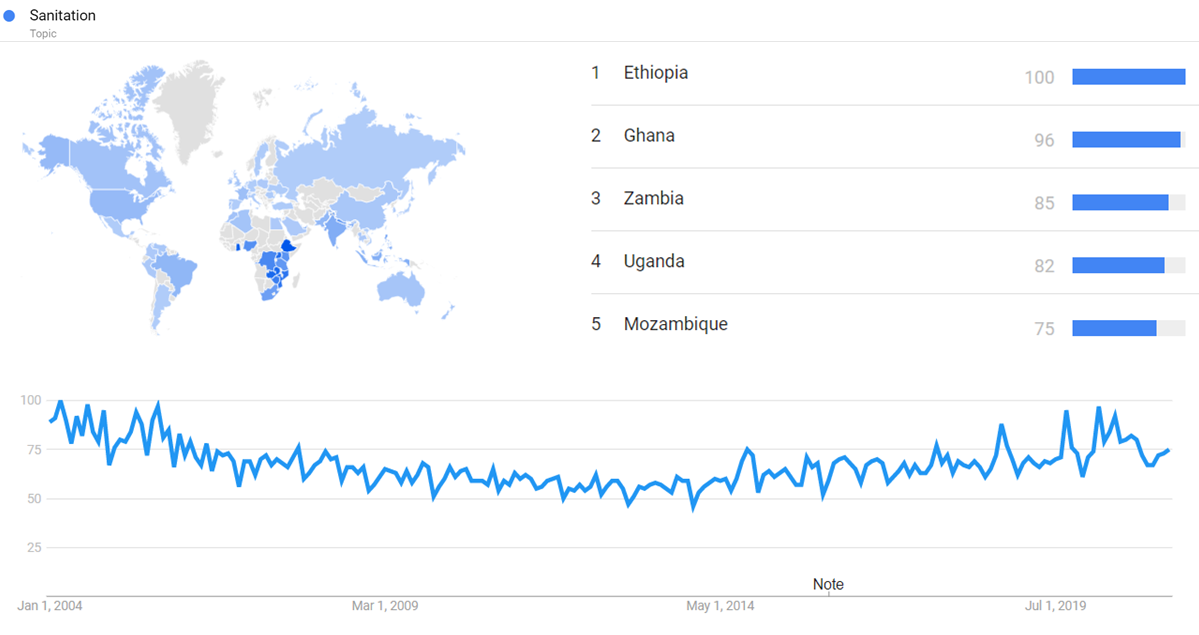

| + | The chart below shows {{w|Google Trends}} data for Sanitation (Topic), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.<ref>{{cite web |title=Sanitation |url=https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=%2Fm%2F019751 |website=Google Trends |access-date=26 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Sanitation gt.png|thumb|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Google Ngram Viewer === | ||

| + | |||

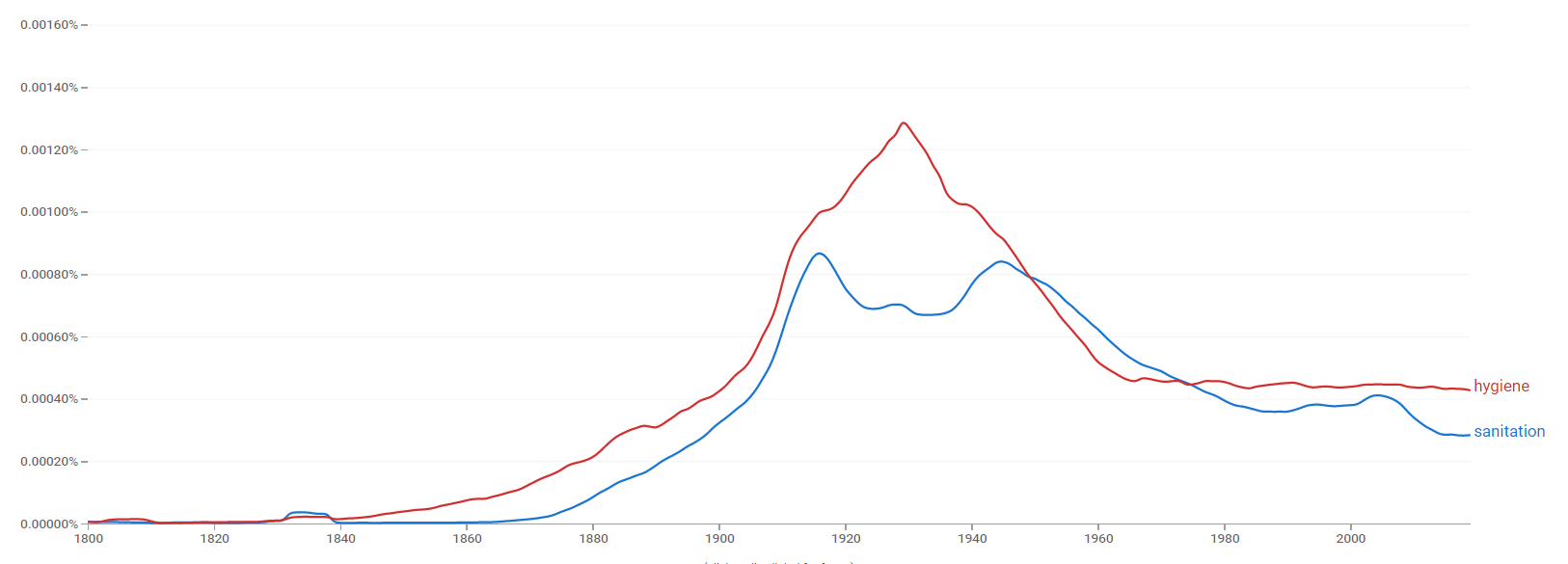

| + | The comparative chart below shows {{w|Google Ngram Viewer}} data for Sanitation and Hygiene, from 1800 to 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Sanitation and Hygiene |url=https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=sanitation%2C+hygiene&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2Csanitation%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Chygiene%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Csanitation%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Chygiene%3B%2Cc0 |website=books.google.com |access-date=26 April 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Sanitation and Hygiene ngram.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Wikipedia Views === | ||

| + | |||

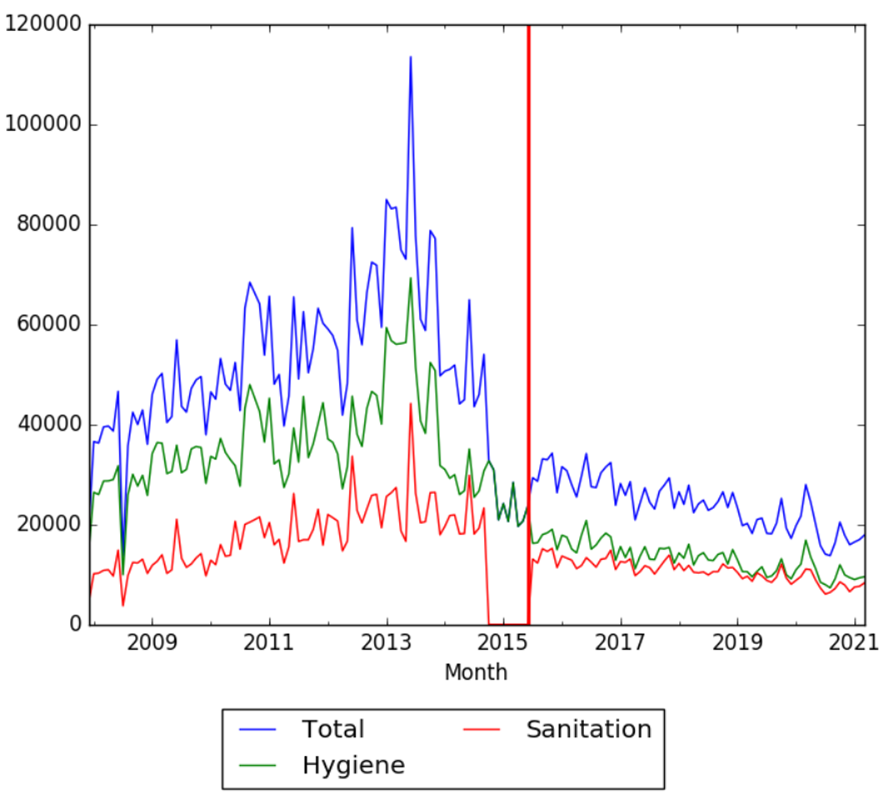

| + | The comparative chart below shows pageviews on desktop of the English Wikipedia articles {{w|Hygiene}} and {{w|Sanitation}}, from December 2007 to March 2021.<ref>{{cite web |title=Hygiene and Sanitation |url=https://wikipediaviews.org/displayviewsformultiplemonths.php?pages[0]=Sanitation&pages[1]=Hygiene&allmonths=allmonths&language=en&drilldown=desktop |website=wikipediaviews.org |access-date=30 April 2021}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Hygiene and sanitation wv.png|thumb|center|450px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Meta information on the timeline== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===How the timeline was built=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The initial version of the timeline was written by [[User:Sebastian]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{funding info}} is available. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===What the timeline is still missing=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * {{w|Dry toilet}} | ||

| + | * {{w|Composting toilet}} | ||

| + | * {{w|Urine-diverting dry toilet}} | ||

| + | * {{w|Pit latrine}} | ||

| + | * {{w|Fecal sludge management}} | ||

| + | * {{w|Swachh Bharat Mission}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Timeline update strategy=== | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 204: | Line 279: | ||

* [[Timeline of water supply]] | * [[Timeline of water supply]] | ||

* [[Timeline of water treatment]] | * [[Timeline of water treatment]] | ||

| + | * [[Timeline of pollution]] | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

Latest revision as of 10:19, 8 December 2022

This is a timeline of sanitation, attempting to describe events covering sewage systems as well as sanitation facilities such as sewage and toilets. Toilet paper is described in the timeline of hygiene. Historical events related to the timeline can be found in the timeline of hygiene, timeline of water supply, timeline of water treatment and timeline of pipeline transport.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Prehistoric times | Early sanitation systems are built in the prehistoric Middle East, in the south-east of actual Iran near Zabol.[1] |

| Ancient times | The oldest Chinese civilization already has pipes and plumbing in the structures.[2] Surface-based storm drainage systems are developed by the Babylonian and Mesopotamian Empires.[3] The Minoans and Harappans in Crete and the Indus valley civilization, all have well organized and operated sewer and drainage systems.[3] Hellenes and Romans are considered pioneers in developing basic sewerage and drainage technologies, with emphasis on sanitation in the urban environment.[3] |

| Medieval times | Following a crisis in the maintenance of the sewers of the Roman cities occurring in the 3rd–4th centuries[3], very little progress is made during the Dark ages, circa 300 AD through to the middle of the 18th century.[3] Small natural waterways in medieval European cities, used for carrying off wastewater, are eventually covered over and function as sewers. Pail closets, outhouses, and cesspits are used to collect human waste. However, most cities do not have a functioning sewer system before the Industrial era, relying instead on nearby rivers or occasional rain showers to wash away the sewage from the streets. |

| 1600s–1700s | Rapid expansion of waterworks and pumping systems take place in Europe.[1] |

| 1800s | Sewer systems begin implementation in many European and US cities, initially discharging untreated sewage to waterways. When discharge of untreated sewerage become increasingly unacceptable, experimentation towards improved treatment methods would result in sewage farming, chemical precipitation, filtration, sedimentation, chemical treatment, and activated sludge treatment using aerobic microorganisms.[4] Earth closets are popular during this time.[5] Around 1850 onwards, modern sewerage is “reborn”, but many of the principles grasped by the ancients are still in use today.[3] Indoor plumbing initiates in Europe and the United States.[6] Late in the century, many cities start constructing extensive sewer systems to help control outbreaks of disease such as typhoid and cholera. Also, some cities begin to add chemical treatment and sedimentation systems to their sewers.[1] Flush toilets come into widespread use late in the century as well.[7] |

| 1900s | Most cities in the Western world add more expensive systems for sewage treatment.[1] |

| Recent years | Worldwide, about 2,4 billion people are estimated to lack sanitation, such as toilets or latrines. Every year, 5 million people die of waterborne diseases, including nearly 1,000 children dying every day due to preventable water and sanitation-related diarrhoeal diseases.[8] At least 1,8 billion people globally use a source of drinking water that is fecally contaminated. More than 80% of wastewater resulting from human activities is discharged into rivers or sea without any pollution removal.[9] |

Full timeline

| Year | Category | Details | Country/location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4000 BC | Technology | The Babylonians introduce clay sewer pipes, with the earliest examples found in the Temple of Bel at Nippur and at Eshnunna, Babylonia.[1] | |

| 4000 BC–2500 BC | Technology | Evidence of surface-based storm drainage systems in early Babylonian and Mesopotamian Empires in Iraq is found.[3] | Iraq |

| 3500 BC | Technology | The making of alloy begins.[10] | |

| 3200 BC–2300 BC | System | In the early Minoan civilization, issues related to sanitary techniques are considered of great importance. Advanced wastewater and stormwater management are practiced. In several Minoan palaces, one of the most important elements is the provision and distribution of water and the removal of waste and stormwater by means of sophisticated hydraulic works. The sewage and drainage systems are mainly stone structures. Stone conduits forme drains which lead rainwater from the courts outside the palaces, to eliminate the risk of flooding.[3] | Greece |

| 3200 BC–2200 BC | System | Early drainage systems are built in Skara Brae, Scotland. Stone huts have drains with cubicles over them, probably used as toilets.[3] | United Kingdom |

| 3000 BC–2700 BC | System | The Indus Valley Civilization shows early evidence of public water supply and sanitation, having developed flushing toilets, along with a working sewer system, to deal with the issues of waste disposal and indoor sanitation.[6][11][3] | India |

| 2600 BC – 1100 BC | System | The ancient Greek civilization of Crete, known as the Minoan civilization, already uses underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply.[1] | |

| 2350 BC | System | The Indus city of Lothal provides all houses with their own private toilet which is connected to a covered sewer network constructed of brickwork held together with a gypsum-based mortar that empties either into the surrounding water bodies or alternatively into cesspits, the latter of which are regularly emptied and cleaned.[12][13][14] | India |

| 2100 BC | System | The Egyptian city if Herakopolis has a system of removal of wastes, organic and inorganic to locations outside the living and/or communal areas, usually to the rivers. Finer houses have bathrooms and toilet seats made of limestone. | Egypt |

| 2100 BC | System | The cities on the island of Crete have trunk sewers connecting homes.[10] | Greece |

| 2000 BC | Publication | Descriptions of of foul water purification by boiling and filtering are written in Sanskrit.[4] | |

| 1800 BC | Technology | The Minoans on Crete and Thera have some toilets flushing with water.[15] | Greece |

| 1200 BC | Technoloogy | Rich Egyptians use a container with sand for toilet, which is emptied by slaves.[16] | Egypt |

| 1200 BC | Material | New materials are introduced with the beginning of the Iron Age.[10] | |

| 1200 BC–700 BC | System | Hattusa, the capital of the hittite Empire, has public waste disposal plumbing around this epoch.[15] | Turkey |

| 1046 – 256 BC | System | During the Zhou Dynasty in ancient China, sewers exist in various cities such as Linzi.[1] | China |

| 900 BC–100 AD | System | The Greeks on the sacred island of Delos have large-scale public plumbing in addition to private latrines flushed by running water in this period.[15] | Greece |

| 800 BC–100 BC | System | The Etruscan civilization has drainage channels on the sides of streets in its towns. The etruscan system is based both on the natural slope of the plateau and on an artificial modification. The Etruscan system is planned in order to avoid water runoff interacting with the two necropolis located between the urban area and the river Reno, where wastewater is usually discharged.[3] | Italy |

| 700 BC–400 AD | System | The Romans develop a very advanced technology for sanitation, including baths with flowing water, and underground sewers and drains. The drains of Rome are intended primarily to carry away runoff from storms and to flush streets. The Cloaca Maxima sewage system, combines three functions: wastewater removal, rainwater removal and swamp drainage. The waste water removed by the city’s sewage system, some of which, like the Cloaca Maxima, is still in use today.[6] The Romans worship Cloacina, the goddess who presides over the Cloaca Maxima ("Greatest Drain"), the main trunk of the system of sewers in Rome.[17] | Italy |

| 206 BC–24 AD | Technology | Latrine use dates back to the Western Han Dynasty. A found toilet with running water, a stone seat and an armrest dates bak from this time.[18][19] | China |

| 200 BC – 100 BC | System | In China Yellow Emperor’s Treatise on Internal Medicine dictates that "it is more important to prevent illness than to cure the illness when it has arisen". Clean water is known to be important in disease prevention so wells are covered, devices are used to filter water and the Chhii Shih (“sanitary police”) removes all animal and human corpses from waterways and buries all bodies found on land.[4] | China |

| 46 BC – 400 AD | System | Roman settlements in the United Kingdom have complex sewer networks sometimes constructed out of hollowed–out elm logs, which are shaped so that they butt together with the down–stream pipe providing a socket for the upstream pipe.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 100 AD | Technology | Roman sewers collect rainwater and sewage. There are public lavatories. [16] | Italy |

| 250 – 900 AD | Technology | The Classic Mayans at Palenque have underground aqueducts and flush toilets.[1] | Mexico |

| 315 AD | Statistics | There are 144 public latrines in Rome.[20] | Italy |

| 1100s | Technology | At Portchester Castle, stone chutes leading to the sea are built by monks. When the tide goes in and out it flushes away the sewage.[21] | United Kingdom |

| 1200 | Technology | In medieval Europe, Toilets in castles consist usually in vertical shafts cut into the thickness of the walls with a stone seat on top.[22] | Europe |

| 1370 | Facility | The first closed sewer constructed in Paris is designed by Hughes Aubird on Rue Montmartre, and is 300 meters long.[1] | France |

| 1388 | Policy | The English Parliament bans dumping of waste in ditches and public waterways.[10] | United Kingdom |

| 1427 | Policy | The first English public Act about sewerage issue is delivered.[20] | United Kingdom |

| 1530 | Policy | Decree issued in Paris requires that each new house must be equipped with a cesspool. Wastewater disposal in Paris starts being regulated.[20] | France |

| 1531 | Facility | Sewage farms (wastewater used for irrigation and fertilizing agricultural land) are operated in Bunzlau, Silesia.[1] | |

| 1596 | Technology | Sir John Harington invents a flush toilet for his godmother Queen Elizabeth I, that releases wastes into cesspools.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1600s – 1700s | Japanese cities collect human waste for use as crop fertilizer. This practice minimizes human contact with waste. Sewage is not discharged to rivers so pollution of waterways is minimized.[4] | Japan | |

| 1636 | Statistics | Report mentions 24 sewers in Paris, of which only 6 are covered, and every of them is clogged or ruined.[20] | France |

| 1650 | Facility | Sewage farms are operated in Edinburgh, Scotland.[4] | United Kingdom |

| 1676 (9 October) | Scientific development | Using the newly invented microscope, Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek reports the discovery of microorganisms. With the microscope, for the first time, small material particles that were suspended in the water can be seen, laying the groundwork for the future understanding of waterborne pathogens and waterborne diseases.[23][24] | Netherlands |

| 1721 | Policy | New decree issued in Paris requires property owners to pay for the cleaning of the covered sewers beneath their buildings.[20] | France |

| 1775 | Technology | Scottish inventor Alexander Cumming is granted a patent for a flushing lavatory.[5] | United Kingdom |

| 1778 | Technology | English inventor Joseph Brahmah designs an improved flushing lavatory.[5][25] | United Kingdom |

| 1789 | System | Paris has about 26 km of sewers, and reservoirs are used to flush away the wastes blocked in the sewers.[20] | France |

| 1833 | Technology | The water closet is first patented in the United States.[25] | United States |

| 1840s | Technology | Indoor plumbing is introduced, mixing human waste with water and flushing it away, eliminating the need for cesspools.[1] | |

| 1842 | Publication | British social reformer Edwin Chadwick publishes his Report on an inquiry into the sanitary condition of the labouring population of Great Britain, in which he early notes scientifically that lack of sanitation leads to disease.[26] | United Kingdom |

| 1852 | Facility | The first modern public lavatory, with flushing toilets, opens in London.[5] | United Kingdom |

| 1854 | Scientific development | English physician Dr John Snow shows that cholera is spread by water.[4] | United Kingdom |

| 1855–1860 | System | The first sewer systems in the United States are built in Chicago and Brooklyn.[1] | United States |

| 1860 | Technology | Frenchman Jean Mouras is credited for the invention of the septic tank system, after having built a prototype fabricated from concrete with piping constructed of clay leading from Mouras home to the septic tank located in his yard. After several years of use, the system becomes successful. In 1881 Mouras would be granted a patent.[27][4] | France |

| 1868 | Facility | Sewage farms are operated in Paris.[4] | France |

| 1868 | Facility | Sewage farms are operated in Berlin.[4] | Germany |

| 1868 | Facility | Sewage farms are operated in different parts of the United States.[4] | United States |

| 1870s–1920s | System | Victorian England implements the first–ever comprehensive urban system as a reaction to a series of cholera pandemics during this epoch.[28] | United Kingdom |

| 1877 | Scientific development | Agricultural chemist Jean Jacques Theophile Schloesing proves that nitrification is a biological process in the soil by using chloroform vapors to inhibit the production of nitrate. This knowledge would have one of its greatest practical applications in the treatment of sewerage.[29] | |

| 1879 | Water treatment | William Soper uses chlorinated lime to treat the sewage produced by typhoid patients.[1] | |

| 1883 | Technology | The vacant/engaged bolt for public toilets is patented.[5] | |

| 1883 | Introduction | The septic tank is introduced in the United States.[27] | United States |

| 1884 | Technology | The first pedestal toilet bowl is made.[5] | |

| 1890 | Facility | The first sewage treatment plant in the United States using chemical precipitation is built in Worcester, Massachusetts.[30]:2[31][1] | United States |