Timeline of water treatment

This is a timeline of water treatment, attempting to describe events related to any process that makes water more acceptable for a specific end-use. For more information on the process of desalination, visit timeline of water desalination.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Ancient times | Methods to improve the taste and odor of drinking water are recorded as early as 4000 BC. Ancient Sanskrit and Greek texts recommend water treatment methods such as filtering through charcoal, exposing to sunlight, boiling and straining.[1] Throughout antiquity, tasty or tasteless, cool, odourless and colourless water is considered the best, while stagnant, marshy water is avoided.[2] |

| 6th Century – 16th Century | There's little development in the water treatment area during this period. In medieval cities wooden plumming is used. The water is extracted from rivers or wells, or from outside the city. Soon, circumstances would become highly unhygenic, because waste and excrements are discharged into the water. Illness and death prevails among people drinking this water. To solve the problem, many would drink water from outside the city, where rivers are unpolluted. This water is carried to the city by so-called water-bearers.[3] |

| 18th Century | Filtration is established as an effective means of removing particles from water. However, the degree of clarity achieved is not measurable at the time.[1] Water filters are made of wool, sponge and charcoal.[3] |

| 19th Century | It becomes clear that water quality has a significant impact on health.[4] The role of water in the transmission of several important diseases – cholera, dysentery, typhoid fever and diarrhoeas – is realized.[2] Slow sand filtration begins to be used regularly in Europe. During the mid to late century, scientists gain a greater understanding of the sources and effects of drinking water contaminants, especially those invisible to the naked eye.[1] The development of steam navigation creates a demand for noncorroding water for boilers.[5] |

| 20th Century | Early in the century, it becomes understood that germs transmit illness, and that chlorinating drinking water could help kill bacteria. Continuous chlorination starts being implemented.[6] |

Full timeline

| Year | Category | Details | Country/location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 BC | Publication | Sanskrit writings describe purification of foul water by boiling in copper vessels, exposure to sunlight, filtering through charcoal, and cooling in earthen vessels.[7] | |

| 1500 BC | Sedimentation | Egyptians use the chemical alum to cause suspended particles to settle out of water.[1] | Egypt |

| 470 BC | Scientific development | Greek scientist Alcmaeon of Croton becomes the first Hellene doctor to state that the quality of water may influence the health of people.[8][2] | Greece |

| 400 BC | Publication | Greek physician Hippocrates publishes his treatise Airs, Waters, Places, which deals with the different sources, qualities and health effects of water.[8] | Greece |

| 384 BC – 322 BC | Scientific development | Greek scientist Aristotle describes an evaporation method used by Greek sailors as a process of desalting seawater.[5] | Greece |

| 98 AD | Publication | Sextus Julius Frontinus, water commissioner of Rome, writes the first engineering report on water supply and treatment.[7] | |

| 250 – 900 AD | Filtration | The Classic Mayans at Palenque use household water filters using locally abundant limestone carved into a porous cylinder, which work very similarly to modern ceramic water filters.[9] | Mexico |

| 701 – 800 | Publication | An Arab writer produces a treatise on distillation.[5] | |

| 1561 – 1626 | Filtration | English scientist Sir Francis Bacon is attributed the first recorded experiment for filtration in modern history. Bacon believes that using sand to filter seawater would purify it. Though his hypothesis prove to be incorrect, it would pave the way towards further studies on clean drinking water filtration.[10] | United Kingdom |

| 1676 | Scientific development | Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first observes water micro organisms.[3] | |

| 1804 | Filtration | John Gibb, the owner of a bleachery in Paisley, Scotland, installs an experimental filter, selling his unwanted surplus to the public. This is the first documented use of sand filters to purify the water supply.[11][12] | United Kingdom |

| 1806 | Filtration | A large water treatment plant operates in Paris. The water settles for 12 hours, before being filtered. Filters consist of sand and charcoal, being both replaced every six hours.[13] | France |

| 1827 | Filtration | Robert Thom invents slow sand filters, which are installed in Greenock, Scotland.[4] | United Kingdom |

| 1829 | Filtration | English engineer James Simpson builds a sand filter for drinking water purification. Simpson's prototype would become widely used around the world[13][4] | United Kingdom |

| 1835 | Chlorination | Scientists realize that adding chlorine to water in controlled portions can help alleviate foul odors.[14] | |

| 1855 | Scientific development | English physician Dr. John Snow proves that cholera is a waterborne disease by linking an outbreak of illness in Londin to a public well that is contaminated by sewage.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1869 | Desalination | The first patent for a desalination process is granted in England.[5] | United Kingdom |

| 1869 | Distillation | The first water-distillation plant is built by the British government at Aden, to supply ships stopping at the Red Sea port.[5] | Yemen |

| 1879 | Chlorination | William Soper uses chlorinated lime to treat the sewage produced by typhoid patients.[9] | |

| 1885–1889 | Scientific development | French microbiologist Louis Pasteur demonstrates the "germ theory" of disease, explaining how microscopic organisms (microbes) could transmit disease through media like water.[1] | France |

| 1887 | Facility | The Lawrence Experiment Station is established in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It's the world's first trial station for drinking water purification and sewage treatment.[15] | United States |

| 1890 | Chlorination | Scientists discover that chlorine is a great disinfectant for drinking water.[14] | |

| 1893 | Chlorination | Early attempts at implementing water chlorination at a water treatment plant are made in Hamburg.[9] | Germany |

| 1893 | The world's first water treatment plant using ozone for drinking water is installed in Ousbaden, Holland.[16] | Netherlands | |

| 1896 | Filtration | An improved method of water filtration arises when American Louisville Water Company starts using coagulation, paired with rapid-sand filtration to successfully filter out 99% of bacteria, leaving water clear, crisp and healthier.[14] | United States |

| 1897 | Chlorination | Maidstone in England becomes the first city to have its entire water supply treated with chlorine.[9] | United Kingdom |

| 1902 | Chlorination | As it becomes understood that germs transmit illness, and that chlorinating drinking water could help kill bacteria, Belgium becomes the first country to implement continuous chlorination.[17] | |

| 1902 | Filtration | Blaisdell Slow Sand Filter Washing Machine at Yuma, Arizona is invented by Hiram W. Blaisdell as a device to wash sand filters used in the treatment of drinking water.[18] | United States |

| 1903 | Chlorination | British officer Vincent B. Nesfield, working in the Indian Medical Service, develops a technique of purification of drinking water by use of compressed liquefied chlorine gas.[19] | India |

| 1903 | Desalination | Water softening is invented as a technique for water desalination.[3] | |

| 1905 | Crisis | Serious typhid fever epidemic breaks out in Lincoln , England. Dr. Alexander Cruikshank Houston uses chlorination of the water to stem the epidemic. This marks the beginning of permanent water chlorination. The same year, the London Metropolitan Water Board starts applying drinking water disinfection after researching the disinfection mechanism of chlorine in water purification, under the view that chlorine disinfection is a suitable alternative for long-term storage of raw water. [9][20][10][9] | United Kingdom |

| 1908 | Chlorination | Chlorination starts implementation in the United States at Boonton reservoir in Jersey City. The courts deem the right to chlorinate water a safeguard to public health, paving the way for the rest of the nation’s drinking water supplies.[14] | United States |

| 1910 | Chlorination | U.S. Army Major Carl Rogers Darnall, a Professor of Chemistry at the Army Medical School, develops the technique of purification of drinking water by use of compressed liquefied chlorine gas.[21] | United States |

| 1913 | Wastewater treatment | The activated sludge process, a type of wastewater treatment process for treating sewage or industrial wastewaters, is first discovered.[22] | United Kingdom |

| 1912 – 1914 | Policy | The Public Health Service Act is passed in the United States, authorizing regular surveys and studies of water pollution. The act is aimed at discovering the dangers water could have on human health. In 1914, the act would introduced the idea of maximum contaminant levels, but only for water supplies serving interstate transportation.[14] | United States |

| 1919 | Publication | Civil engineer Abel Wolman and chemist Linn H. Enslow of the Maryland Department of Health in Baltimore publish an article describing a test for chlorine absorption, thus establishing a controlled method of chlorination of municipal water supplies. To determine the correct dose, Wolman and Enslow would analyze the bacteria, acidity, and factors related to taste and purity. This process would eventually transform water treatment and later bring safe water supplies to much of the world.[23][24] | United States |

| 1930 | Desalination | The first large-scale desalination plant is built in Aruba.[5] | |

| 1938 | Desalination | The first modern desalination plant is built in Saudi Arabia.[25] | Saudi Arabia |

| 1947 | Technology | American company eerie Water Treatment starts developing and manufactoring an automatic regeneration control valve for water softeners.[26] | United States |

| 1948 | Publication | American author Moses Nelson Baker publishes The Quest for Pure Water: The History of Water Purification from the Earliest Records to the Twentieth Century, which is a milestone on history of water filtration. The book is still in use today. | United States |

| 1951 | Policy | Water fluoridation becomes an official policy of the United States Public Health Service. By 1960, water fluoridation would become widely used in the country, reaching about 50 million people.[9] | United States |

| 1953 | Policy | Water fluoridation is introduced in Brazil. By 2004 71% of the population would have access to it.[9] | Brazil |

| 1959 | Facility | American company CDM Smith designs the first dual–media, multiple–tray water treatment plant.[27] | United States |

| 1960s | Desalination | Kuwait becomes the first state in the Middle East to begin using seawater desalination technology, providing with both fresh water and electric power using a technology known as multistage flash (MSF) evaporation. The MSF process begins with heating saltwater, which occurs as a byproduct of producing steam for generating electricity, and ends with condensing potable water. Between the heater and condenser stages are multiple evaporator-heat exchanger subunits, with heat supplied from the power plant external heat source. During repeated distillation cycles cold seawater is used as a heat sink in the condenser.[23] | Kuwait |

| 1962 | Policy | The Public Health Service Drinking Water Standards Revision is passed in the United States, setting forth the minimum requirements that public water suppliers must meet."[14] | United States |

| 1968 | Filtration | The Jardine Water Purification Plant begins functioning. Located in Chicago Illinois it is the largest capacity water filtration plant in the world.[28] | United States |

| 1977 | Organization | The Mar del Plata United Nations Conference on Water becomes the first intergovernmental water conference.[29] | Argentina |

| 1980s | Wastewater treatment | South African engineer James Barnard develops the Bardenpho process, a wastewater treatment process that removes nitrates and phosphates from wastewater without the use of chemicals. The process converts the nitrates in activated sludge into nitrogen gas, which is released into the air, removing a high percentage of suspended solids and organic material.[23] | |

| 1980 | Crisis | A hepatitis A outbreak surges due to the consumption of water from a feces-contaminated well, in Pennsylvania.[30] | United States |

| 1987 | Crisis | The 1987 Carroll County Cryptosporidiosis outbreak in western Georgia is caused by the public water supply of which the filtration was contaminated.[31] | United States |

| 1987 | Funding | The United States Congress establishes the Clean Water State Revolving Fund in the Water Quality Act of 1987 as a self–perpetuating loan assistance authority for water quality improvement projects in the United States.[32] | United States |

| 1987 | Technology | Advanced oxidation process (AOP) is introduced as a set of processes that "involve the generation of hydroxyl radicals in sufficient quantity to affect water purification".[33] | |

| 1988 | Crisis | Many people become poisoned through contaminated drinking water supply in Camelford, after a worker puts 20 tonnes of aluminium sulphate in the wrong tank. | United Kingdom |

| 1993 | Crisis | 400,000 people fall ill in Milwaukee from using drinking water that is contaminated by Cryptosporidium cysts.[34] | United States |

| 1993 | Crisis | Overfeeding of fluoride results in a fluoride poisoning outbreak, in Mississippi.[35] | United States |

| 1996 | Technology | Indian scientist Ashok Gadgil, working at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, invents the UV Waterworks, an effective and inexpensive device for purifying water. The device, a portable, low-maintenance, energy-efficient water purifier, uses ultraviolet light to quickly, safely, and cheaply disinfect water of the viruses and bacteria that cause cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and other deadly diseases.[23][36] | United States |

| 2000 | Crisis | A gastroenteritis outbreak is brought by a non-chlorinated community water supply, in southern Finland.[37] | Finland |

| 2001 | Statistics | At the end of the year, there are 15,223 completed or contracted plants worldwide, with fresh water production capacity of more than 6.8 billion gallons of water daily. Nearly 60% of that capacity uses, or will use seawater, with the remaining using brackish or other feedwater.[25] | |

| 2004 | Crisis | Contamination of the community water supply, serving the Bergen city centre of Norway, is reported after the outbreak of waterborne giardiasis.[38] | Norway |

| 2005 | Statistics | More than 10,500 desalination plants producing a total of more than 55 billion litres (in excess of 14.6 billion gallons) of potable water per day are in operation throughout the world.[5] | |

| 2007 | Crisis | Contaminated drinking water leads to the outbreak of gastroenteritis with multiple aetiologies in Denmark.[39] | Denmark |

| 2010 | Statistics | The largest producers of desalinated water are Saudi Arabia, with 17% of total global output, the United Arab Emirates, with 13.4%, and the United States, with roughly 13 percent of the total output (mostly in Florida, Texas, and California). The majority of all desalination plants are reverse-osmosis systems, with multistage flash distillation being the second-ranking process.[5] | |

| 2012 | Statistics | 502,000 diarrhoea deaths are estimated to be caused by inadequate drinking water.[40] | |

| 2015 | Statistics | Some 18,426 desalination plants are reported to operate worldwide, producing 86.8 million cubic meters per day, providing water for 300 million people.[41] |

Numerical and visual data

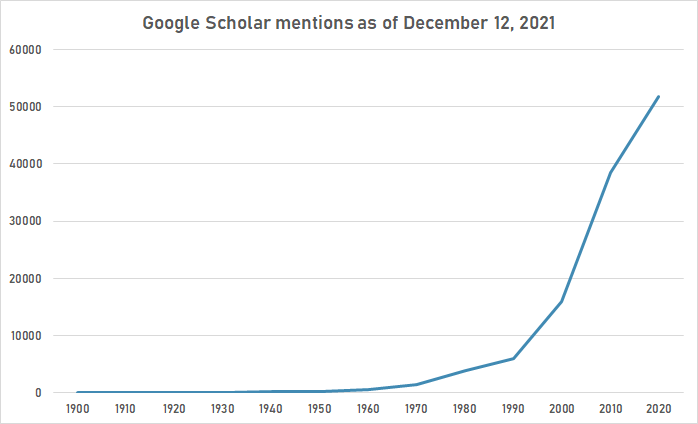

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 12, 2021.

| Year | "water treatment" |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 35 |

| 1910 | 46 |

| 1920 | 57 |

| 1930 | 92 |

| 1940 | 165 |

| 1950 | 251 |

| 1960 | 609 |

| 1970 | 1,440 |

| 1980 | 3,930 |

| 1990 | 6,020 |

| 2000 | 16,000 |

| 2010 | 38,500 |

| 2020 | 51,800 |

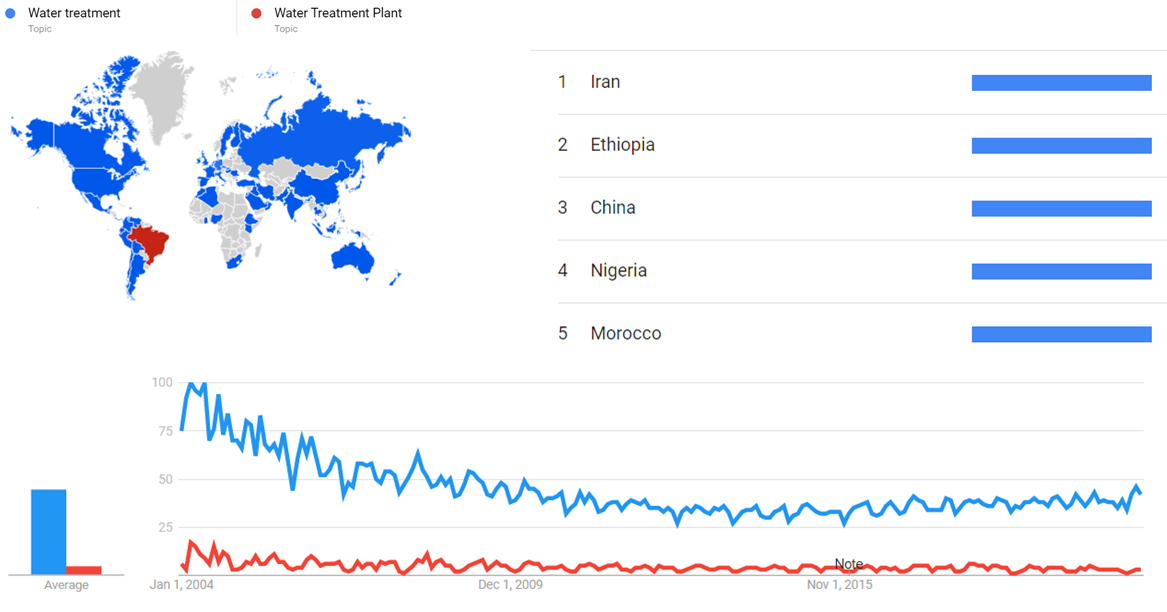

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Water treatment (Topic) and Water Treatment Plant (Topic), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[42]

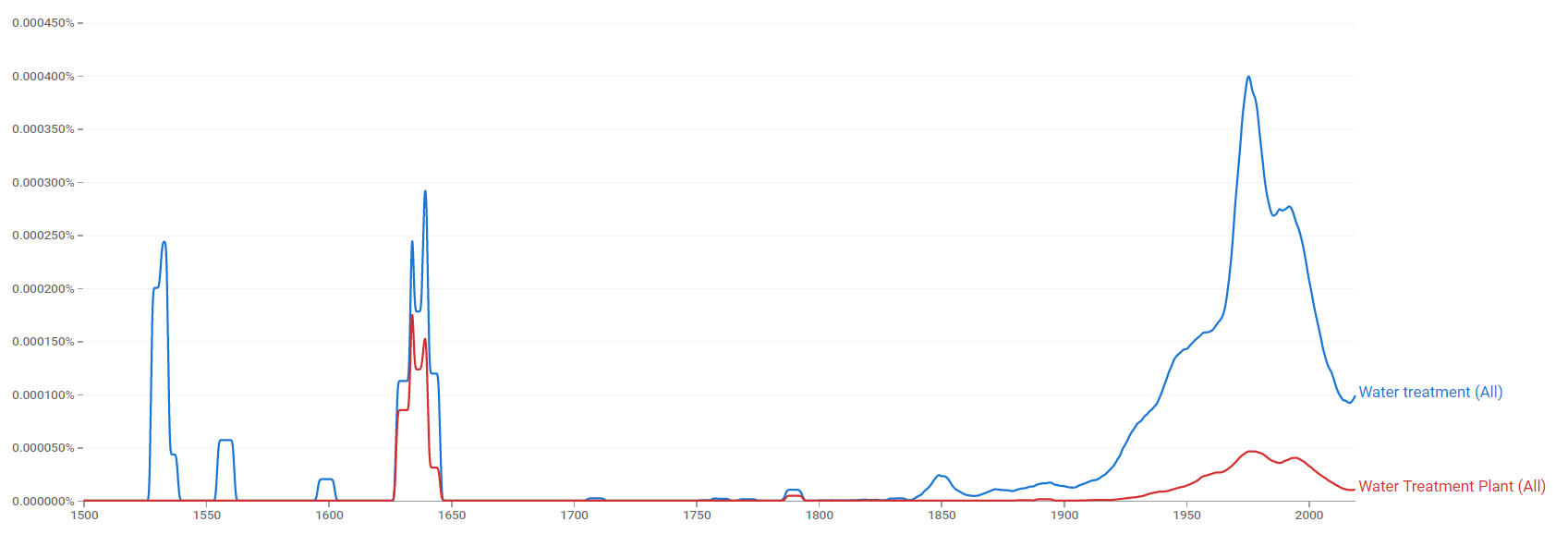

Google Ngram Viewer

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Water treatment and Water Treatment Plant, from 1500 to 2019.[43]

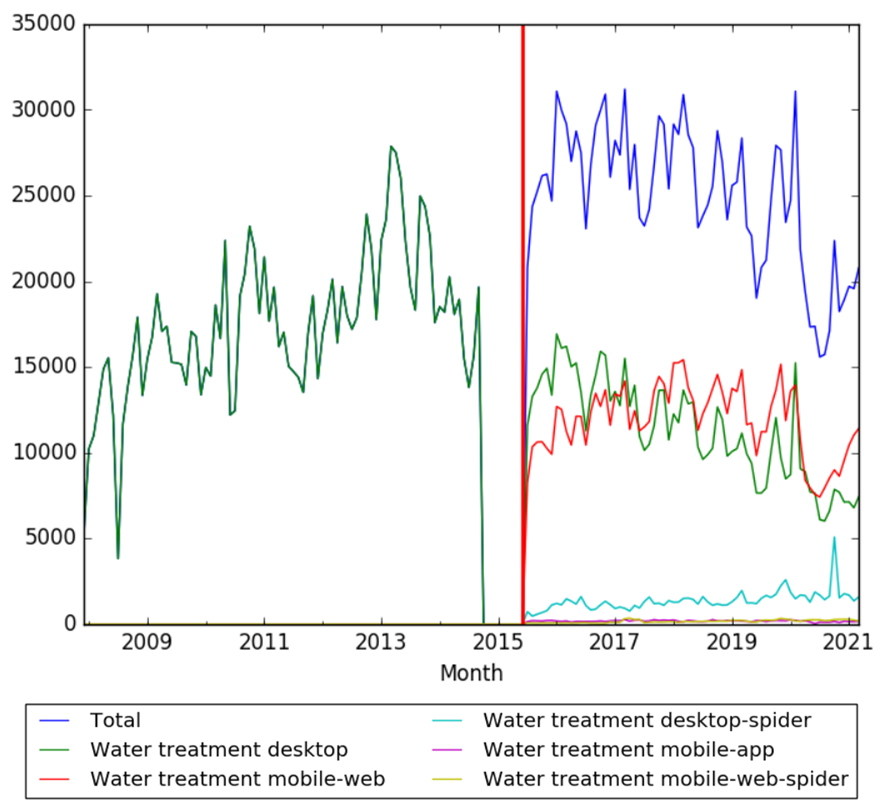

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Water treatment, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to March 2021. A data gap observed on desktop from October 2014 to June 2015 is the result of Wikipedia Views failure to retrieve data.[44]

Other

-

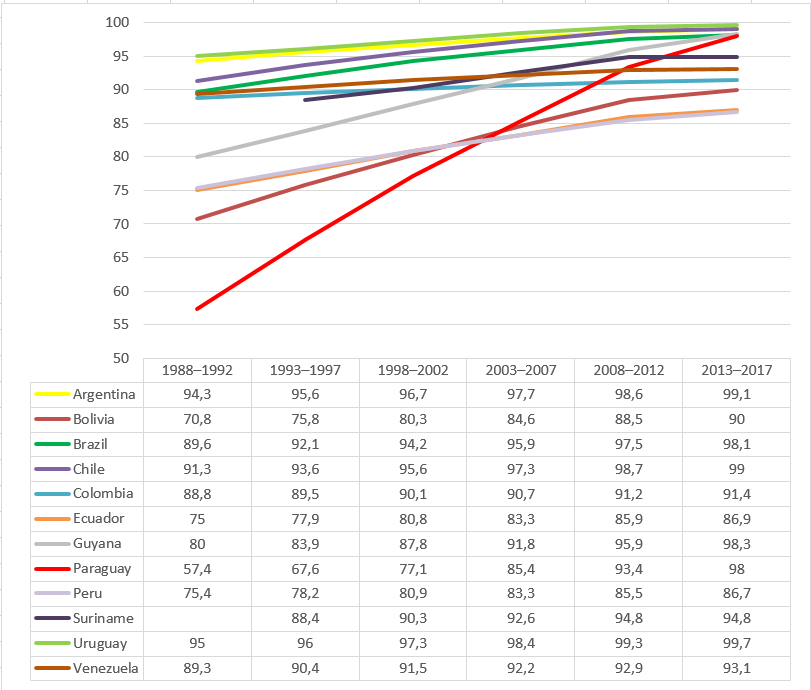

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among South American countries.

-

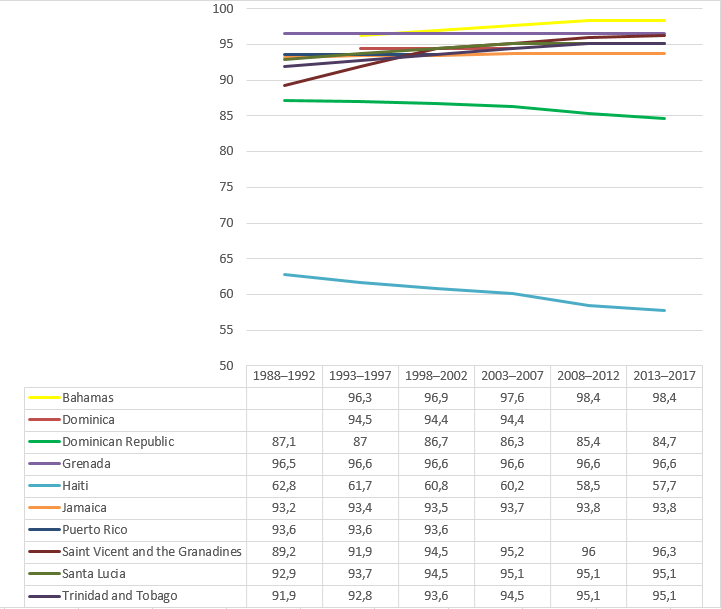

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among American insular countries.

-

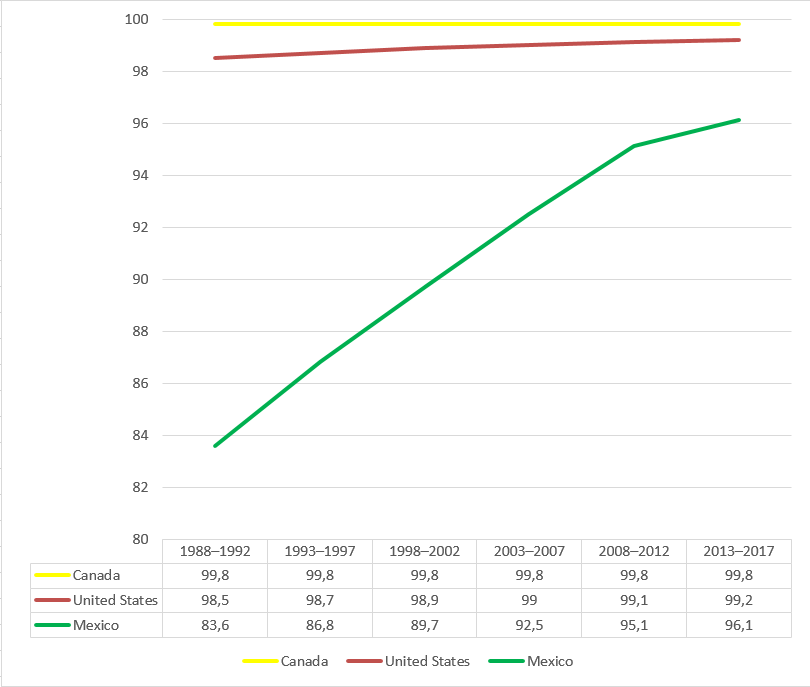

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in North America.

-

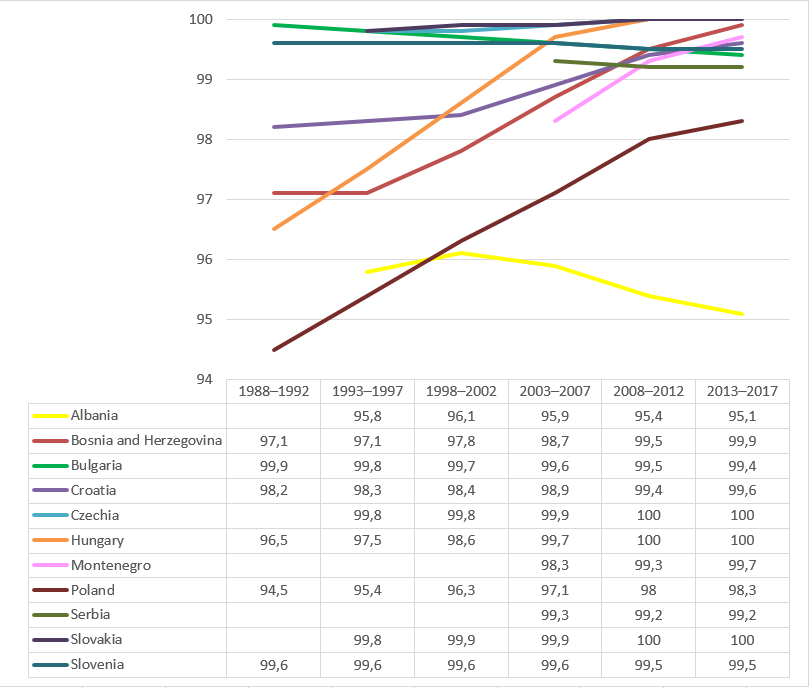

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries from Eastern Europe.

-

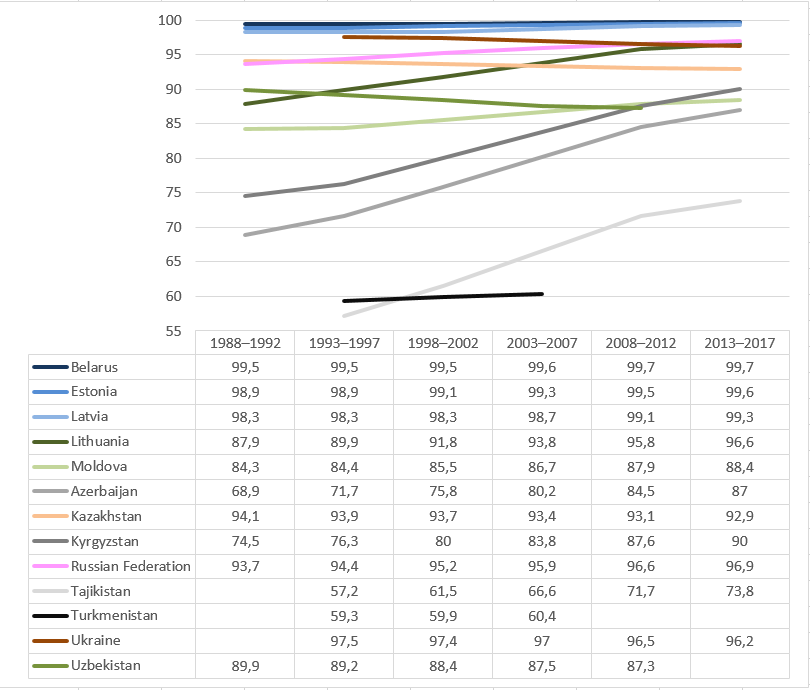

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries belonging to the ex USSR.

-

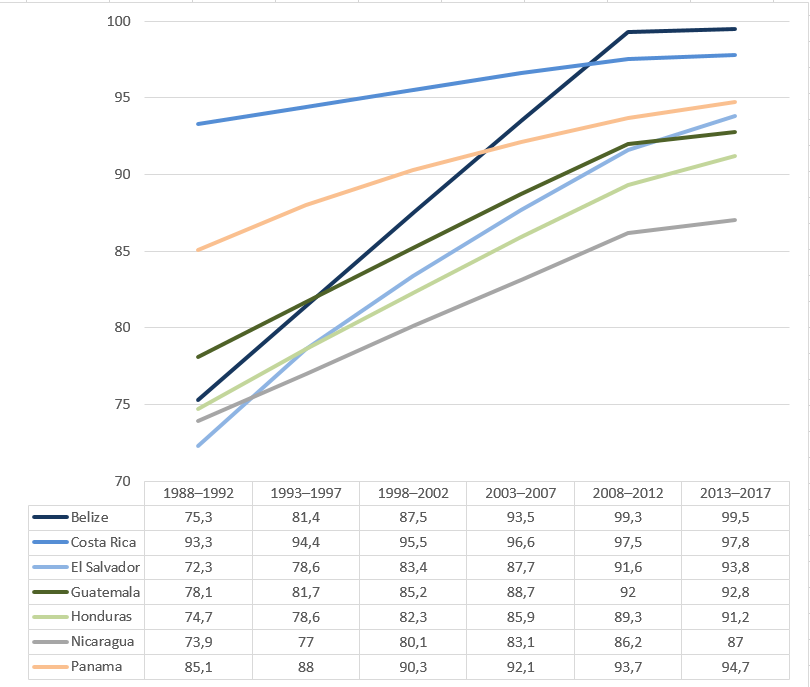

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among Central American countries.

-

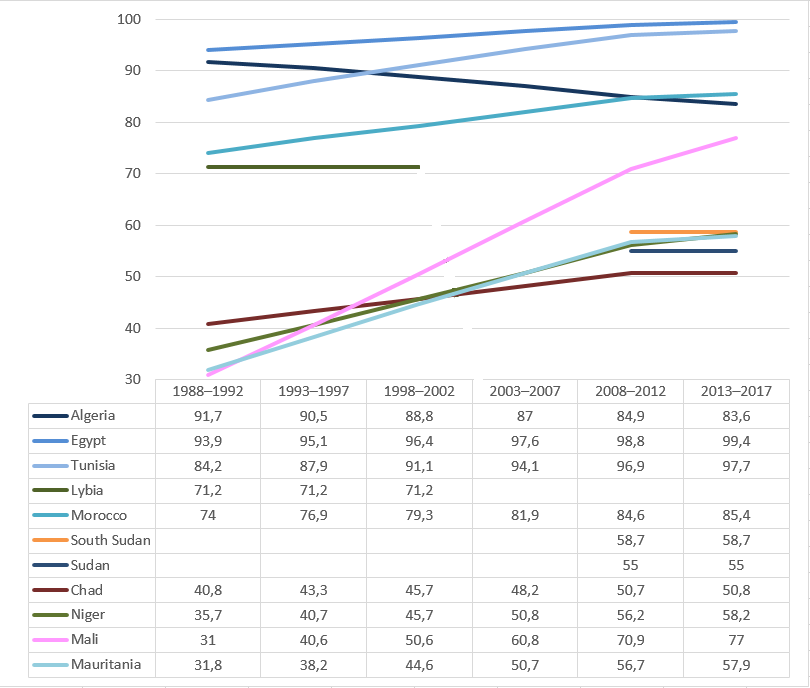

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among Northern African countries.

-

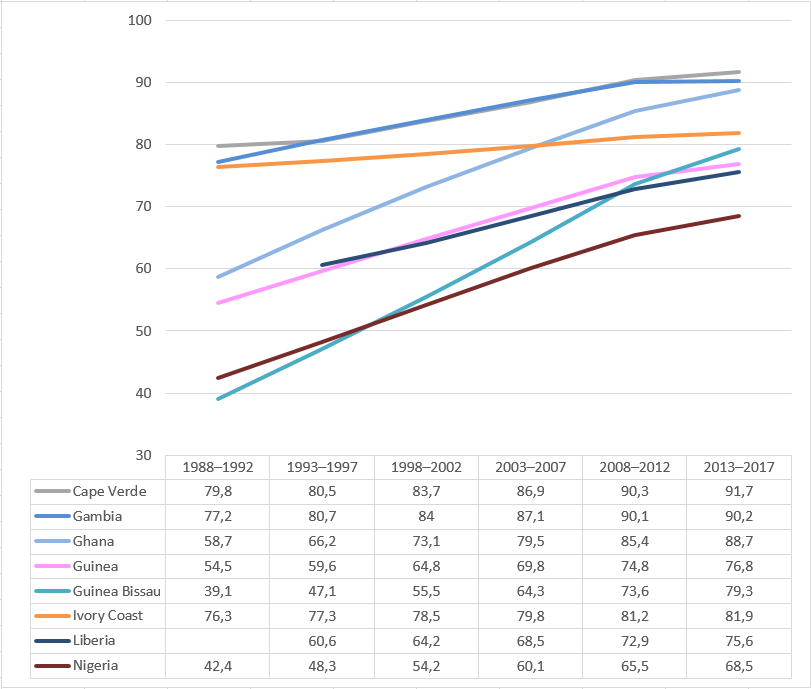

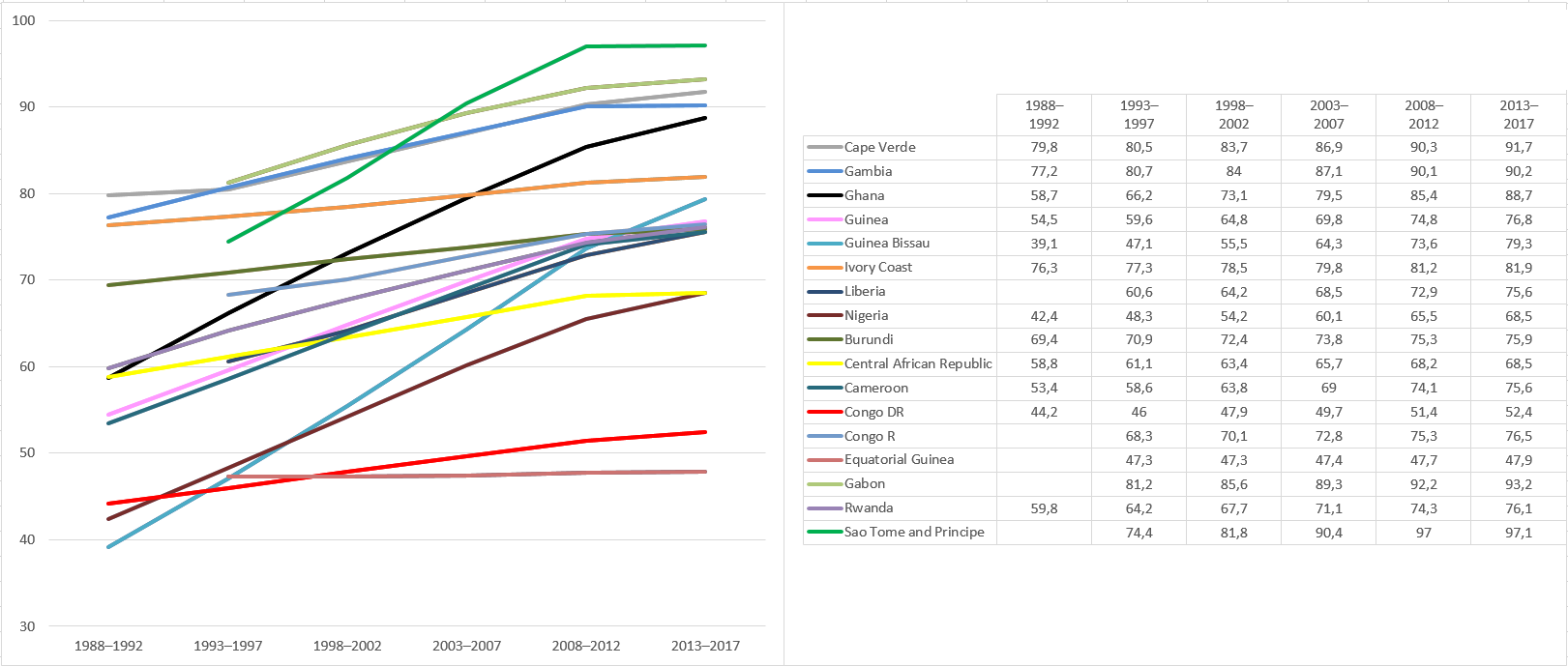

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in Western Africa.

-

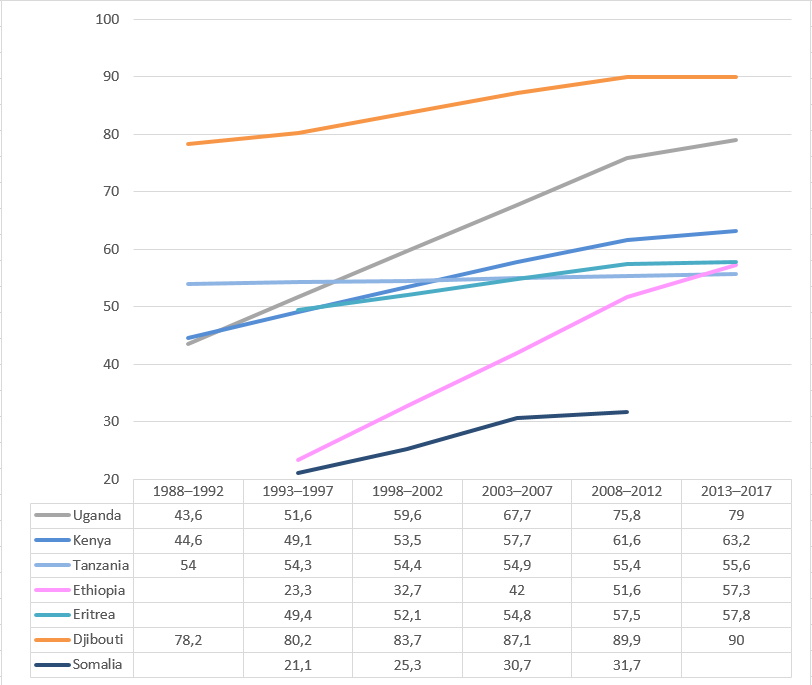

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in Eastern Africa.

-

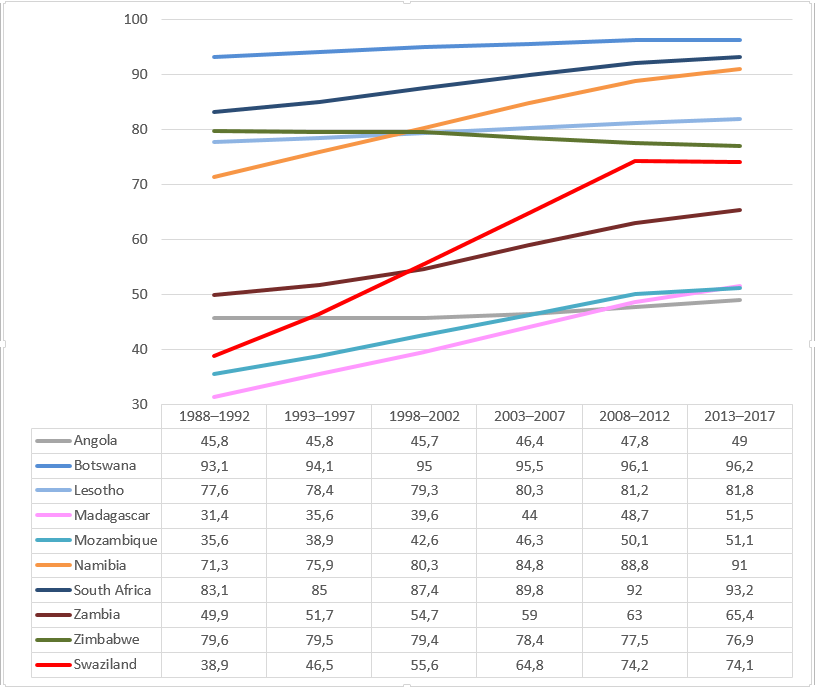

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in Southern Africa.

-

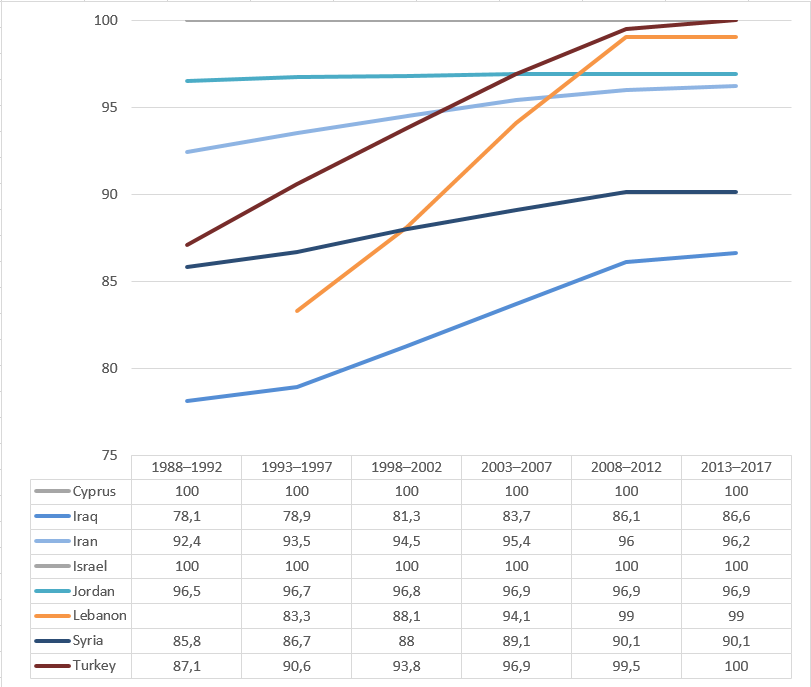

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in West Asia.

-

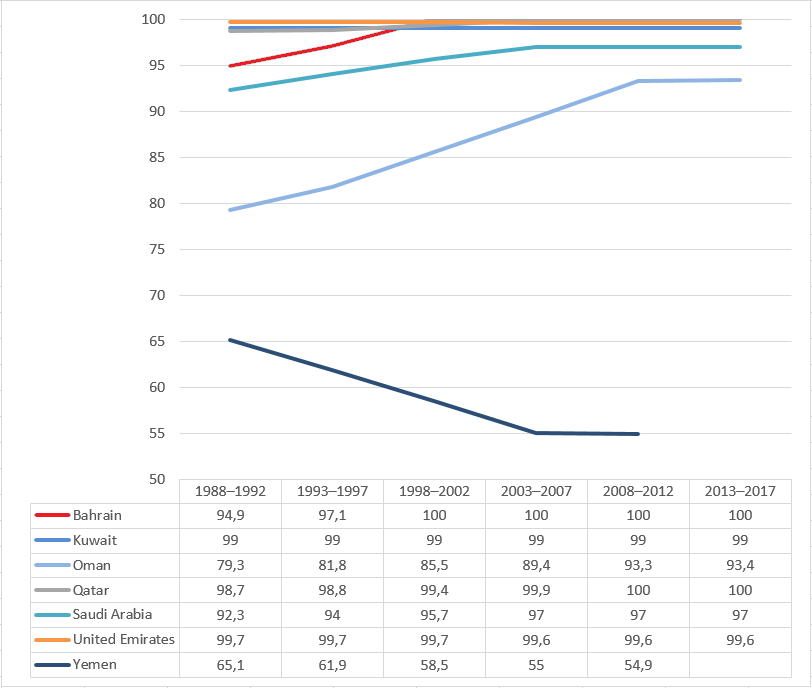

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in the Arabian peninsula.

-

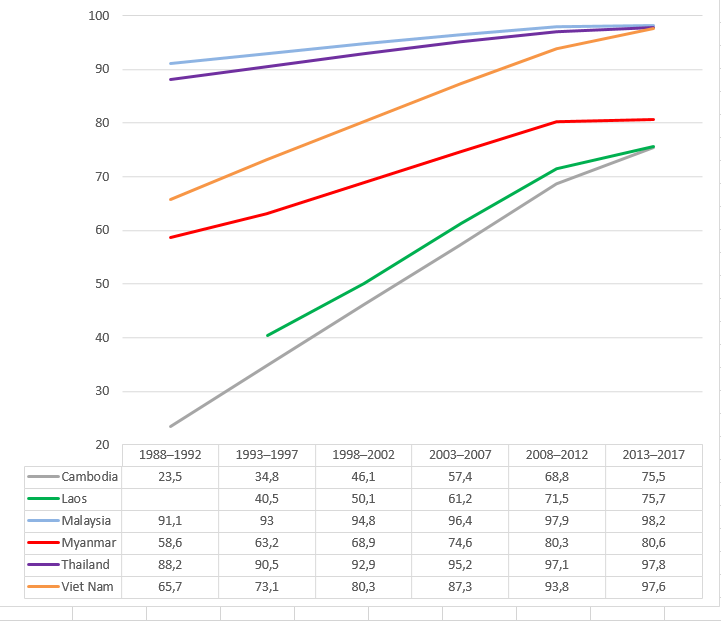

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in continental South East Asia.

-

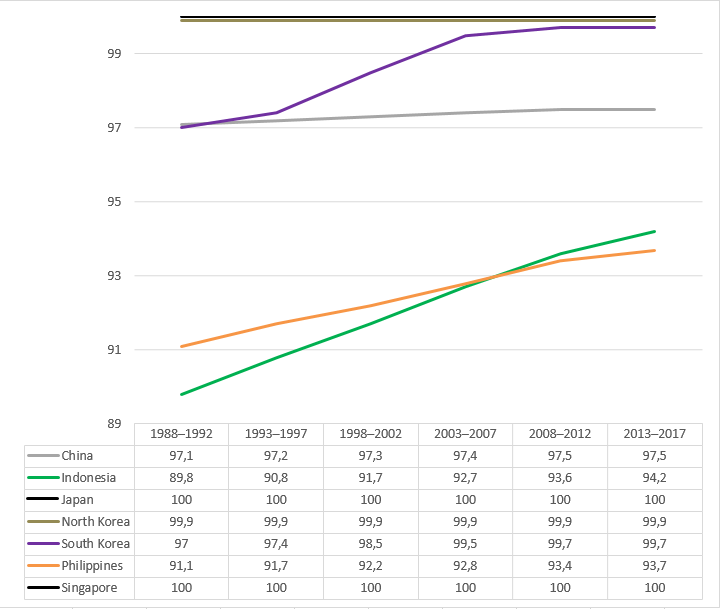

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in continental and insular East Asia.

-

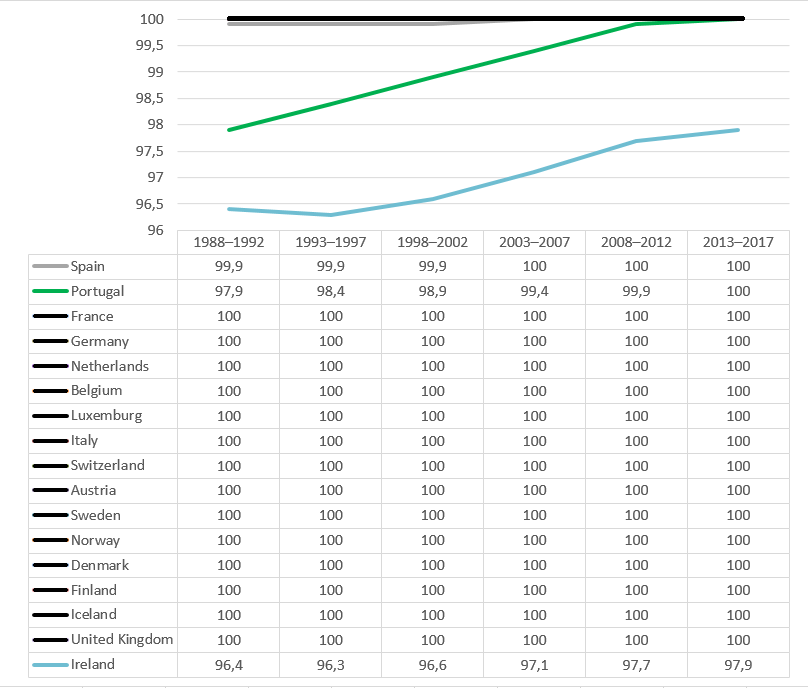

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water in advanced European economies.

-

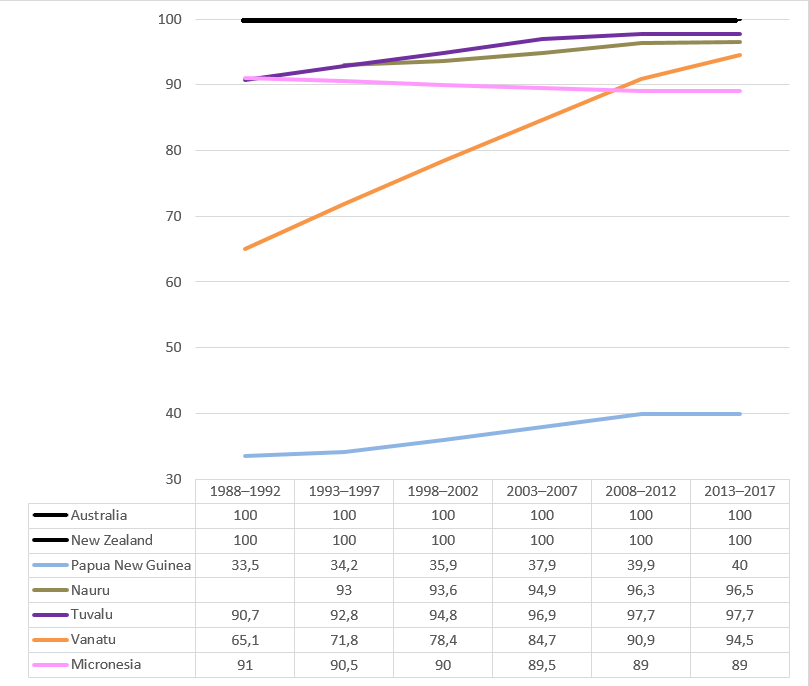

Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water among countries in Oceania.

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

- Timeline of water supply

- Timeline of water desalination

- Timeline of sanitation

- Timeline of irrigation

- Timeline of pollution

- Timeline of waste management

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "The History of Drinking Water Treatment". epa.gov. National Service Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP). Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "A Brief History of Water and Health from Ancient Civilizations to Modern Times". iwapublishing.com. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "History of water treatment". lenntech.com. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "THE HISTORY OF CLEAN DRINKING WATER". freedrinkingwater.com. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "Desalination". britannica.com. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "Chlorine d isinfection of w ater s upplies in the UK" (PDF). ciwem.org. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Verma, Subhash; et al. Water Supply Engineering. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 De Feo, Giovanni; Antoniou, George; Fardin, Hilal Franz; El-Gohary, Fatma; Zheng, Xiao Yun; Reklaityte, Ieva; Butler, David; Yannopoulos, Stavros; Angelakis, Andreas N. "The Historical Development of Sewers Worldwide". doi:10.3390/su6063936. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Burke, Joseph. FLUORIDATED WATER CONTROVERSY. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "How drinking water has improved over the last 100 years". aquafil.com.au. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Filtration of water supplies (PDF), World Health Organization

- ↑ Buchan, James. (2003). Crowded with genius: the Scottish enlightenment: Edinburgh's moment of the mind. New York: Harper Collins.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "History of drinking water treatment". lenntech.com. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 "Drinking Water History Milestones". aquariuswaterconditioning.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ "William X. Wall Experiment Station (WES)". mass.gov. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Rogers, Wayne J. Healthcare Sterilisation: Introduction & Standard Practices, Volume 1, Volume 1.

- ↑ "Chlorine d isinfection of w ater s upplies in the UK" (PDF). ciwem.org. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Baker, T. Lindsay. "Blaisdell Slow Sand Filter Washing Machine". arstudio.eu. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ V. B. Nesfield (1902). "A Chemical Method of Sterilizing Water Without Affecting its Potability". Public Health: 601–3.

- ↑ "Water disinfection application standards (for EU)". lenntech.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Textbooks of Military Medicine: Military Preventive Medicine, Mobilization and Deployment, V. l, 2003. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. LCCN 67019834.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Water Supply and Distribution Timeline". greatachievements.org. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Fee, Elizabeth. "Abel Wolman (1892-1989): Sanitary Engineer of the World". Am J Public Health. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.190876. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Norton, Nancy A.; Sadiq, Abdul-Akeem; Norton, Virgil J. "DESALINATION AS A WATER SOURCE F O R MUNICIPAL AND INDUSTRIAL WATER USERS : THE FUTURE IS NOW" (PDF). gatech.edu. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "ERIE WATER TREATMENT" (PDF). eriewatertreatment.com. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "History". cdmsmith.com. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "How Chicago Purifies One Million Gallons of Water Every Minute". gizmodo.com. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ "Giving an audible voice to water".

- ↑ Bowen GS, McCarthy MA (June 1983). "Hepatitis A associated with a hardware store water fountain and a contaminated well in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1980". Am. J. Epidemiol. 117 (6): 695–705. PMID 6859025.

- ↑ Hayes EB, Matte TD, O'Brien TR, et al. (May 1989). "Large community outbreak of cryptosporidiosis due to contamination of a filtered public water supply". N. Engl. J. Med. 320 (21): 1372–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM198905253202103. PMID 2716783.

- ↑ "Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) Results". epa.gov. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment". researchgate.net. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "Waterborne diseases". lenntech.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Penman AD, Brackin BT, Embrey R (1997). "Outbreak of acute fluoride poisoning caused by a fluoride overfeed, Mississippi, 1993". Public Health Rep. 112 (5): 403–9. PMC 1381948. PMID 9323392.

- ↑ "UV Waterworks: Purifying Water and Saving Lives around the World". lbl.gov. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Kuusi M, Klemets P, Miettinen I, et al. (April 2004). "An outbreak of gastroenteritis from a non-chlorinated community water supply". J Epidemiol Community Health. 58 (4): 273–7. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.009928. PMC 1732716. PMID 15026434.

- ↑ Nygård K, Schimmer B, Søbstad Ø, et al. (2006). "A large community outbreak of waterborne giardiasis-delayed detection in a non-endemic urban area". BMC Public Health. 6: 141. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-141. PMC 1524744. PMID 16725025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Vestergaard LS, Olsen KE, Stensvold R, et al. (March 2007). "Outbreak of severe gastroenteritis with multiple aetiologies caused by contaminated drinking water in Denmark, January 2007". Euro Surveill. 12 (3): E070329.1. PMID 17439795.

- ↑ Prüss-Ustün, A; Bartram, J; Clasen, T; Colford, JM Jr; Cumming, O; Curtis, V; Bonjour, S; Dangour, AD; De France, J; Fewtrell, L; Freeman, MC; Gordon, B; Hunter, PR; Johnston, RB; Mathers, C; Mäusezahl, D; Medlicott, K; Neira, M; Stocks, M; Wolf, J; Cairncross, S. "Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries". doi:10.1111/tmi.12329. PMC 4255749. PMID 24779548. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Desalination by the Numbers". idadesal.org. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ "Water treatment and Water Treatment Plant". Google Trends. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "Water treatment and Water Treatment Plant". books.google.com. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "Water treatment". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.