Difference between revisions of "Timeline of cardiovascular disease"

(→Visual data) |

(→Visual data) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | == | + | == Numerical and visual data == |

| + | |||

| + | === Mentions on Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 20, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! Cardiovascular disease | ||

| + | ! Diabetes cardiovascular disease | ||

| + | ! Hypertensive cardiovascular disease | ||

| + | ! Cardiovascular disease prevention | ||

| + | ! Cardiac arrest | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2002 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2004 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2006 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2008 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2012 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2014 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2016 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2017 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2018 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2019 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || || || || || || || || || || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

=== Google Trends === | === Google Trends === | ||

Revision as of 16:33, 20 May 2021

This is a timeline of cardiovascular disease, focusing on scientific development and major worldwide organizations and events concerning CVD.

Contents

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Prior to 1400s | Descriptions of heart failure exist from Ancient Egypt, Greece, and India. The Romans are known to use the foxglove as medicine.[1] |

| 1400s–1700s | Early discoveries of coronary artery disease start to happen. Among the most important works, are those made by William Harvey and Friedrich Hoffmann.[2] |

| 1700s–1800s | Angina is described and studied extensively in the 18th and 19th centuries. Work by cardiologist William Osler stands out.[2] |

| 1900s | Period of increased interest, study, and understanding of heart disease. Catheters start to be used to explore coronary arteries.[2] |

| 1940s–1950s | The International Society of Cardiology is designed, and the World Congress of Cardiology starts to be held. The link between heart disease and diet is discovered.[2] |

| 1960s–Present | Bypass surgery, angioplasty, and stents are developed. As a result of these treatment advances, a diagnosis of heart disease today is no longer necessarily a death sentence. Still, cardiovascular diseases remain by far the main cause of death worldwide.[2][3] |

Numerical and visual data

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 20, 2021.

| Year | Cardiovascular disease | Diabetes cardiovascular disease | Hypertensive cardiovascular disease | Cardiovascular disease prevention | Cardiac arrest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | ||||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||||

| 2020 |

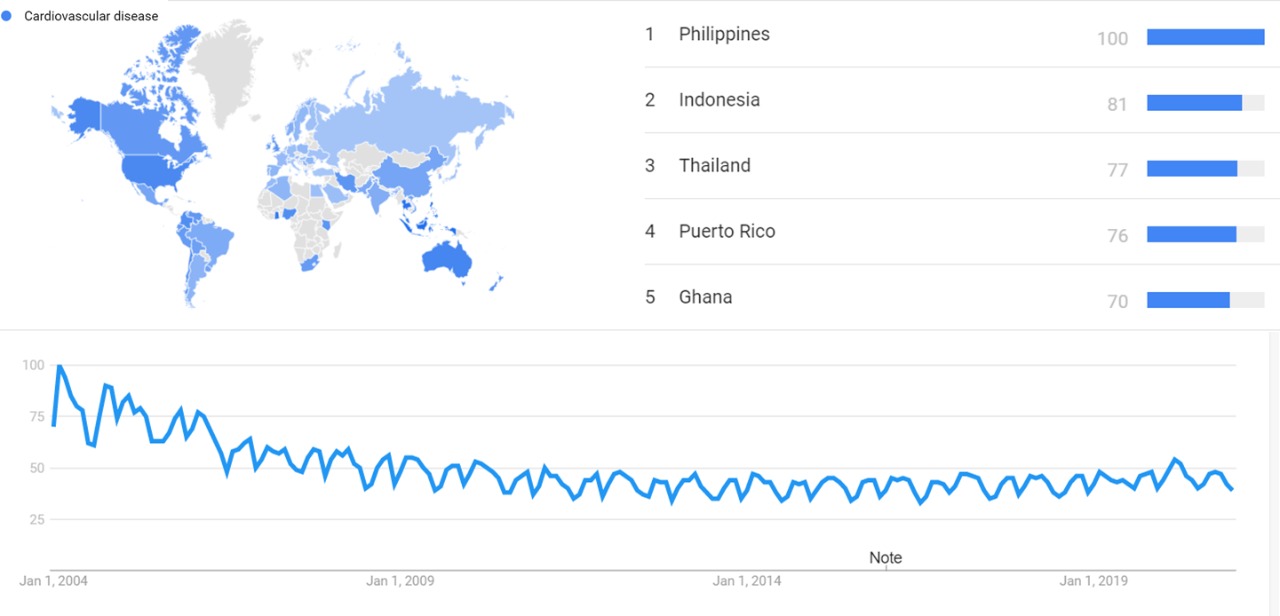

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data for Cardiovascular disease (disease) from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[4]

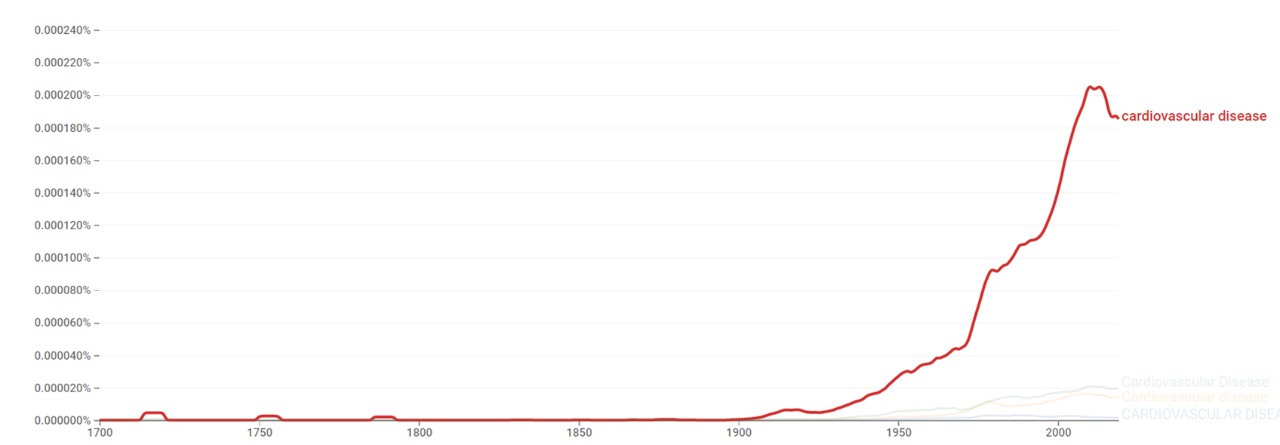

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Cardiovascular disease from 1700 to 2019.[5]

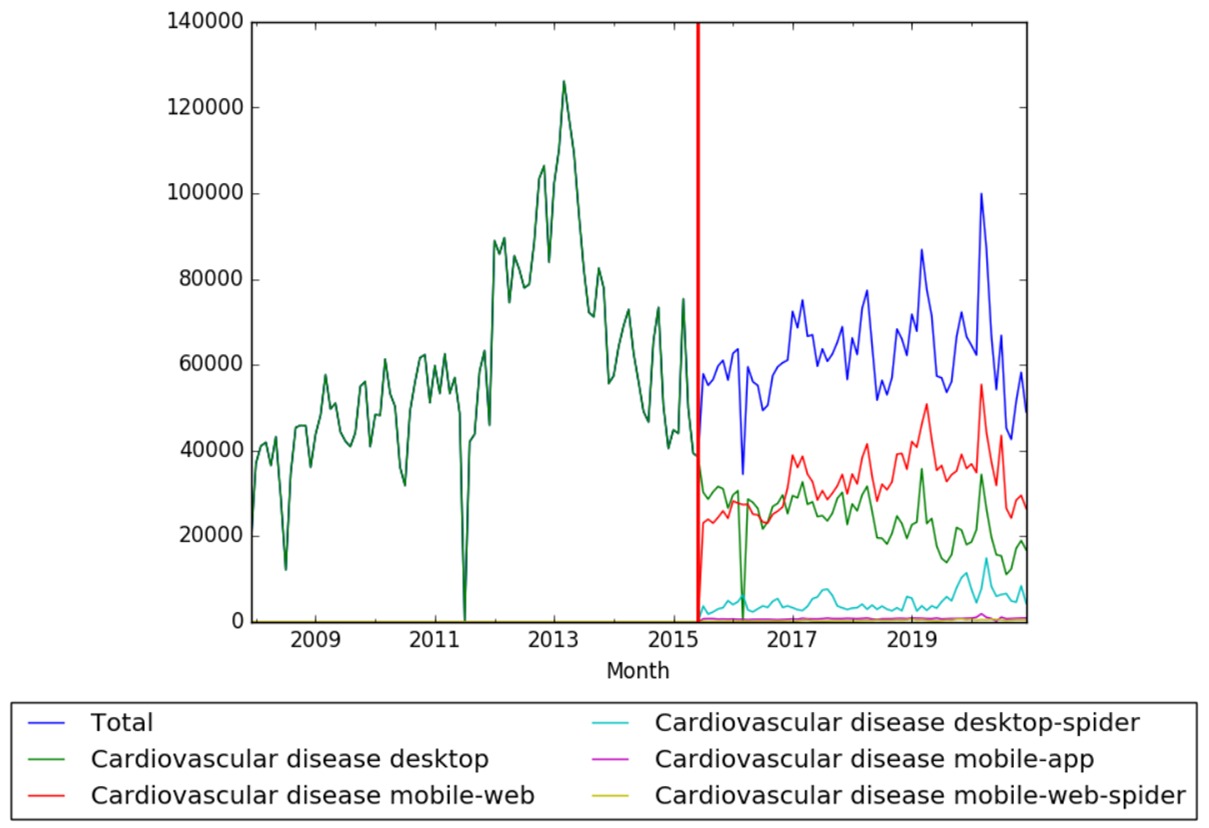

Wikipedia views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Cardiovascular disease on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from June 2015; to December 2020.[6]

Full timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1628 | Scientific development | English physician William Harvey describes in detail the systemic circulation and properties of blood being pumped to the brain and body by the heart.[1] | |

| 1658 | Scientific development | Swiss physician Jakob Wepfer describes for the first time carotid thrombosis, extracranially and intracranially, in a patient with a completely occluded and calcified right internal carotid artery.[7] | |

| 1681–1742 | Scientific development | German physician Friedrich Hoffmann notes that coronary heart disease starts in the “reduced passage of the blood within the coronary arteries."[2] | Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg |

| 1733 | Medical development | English clergyman and scientist Stephen Hales measures blood pressure.[8] | Teddington, England |

| 1768 | Scientific development | English physician William Heberden describes angina pectoris for the first time.[9] | Royal College of Physicians, London |

| 1785 | Medical development | English physician William Withering publishes an account of medical use of digitalis, which are used for the treatment of heart conditions.[1] | |

| 1803 | Medical development | British surgeon David Fleming performs the first successful ligation of a carotid artery.[7] | |

| 1812 | Scientific development | French physician César Julien Jean Legallois proposes the idea of artificial circulation.[10] | |

| 1819 | Development | French physician René Laennec invents the stethoscope, an acoustic device for listening internal sounds of an animal or human body.[1] | Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, Paris |

| 1831 | Discovery | English physician Richard Bright describes high blood pressure and heart disease in association with kidney disease (Bright's disease).[11] | |

| 1872-1919 | Development | Canadian physician William Osler works extensively on angina, and is one of the first to indicate that angina is a syndrome rather than a disease in itself.[2] | |

| 1882 | Medical development (device) | German Von Schröder introduces the first bubble oxygenator.[10] | |

| 1895 | Scientific development | German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovers X-rays, which are used to diagnose heart disease.[1] | |

| 1901 | Scientific development | Dutch physiologist Willem Einthoven invents the string galvanometer, which becomes the first practical electrocardiograph.[1] | Leiden, Netherlands |

| 1920 | Medical development | Organomercurial diuretics are first used for treatment of heart failure.[1] | |

| 1924 | Organization | The Association for the Prevention and Relief of Heart Disease is established.[12] | New York City |

| 1926 | Organization | The Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute is founded.[13] | Melbourne, Australia |

| 1929 | Medical development | German surgeon Werner Forssmann develops the technique of cardiac catheterization. For this achievement, Forssmann will receive the Nobel Prize in 1956.[14][10] | Eberswalde, Germany |

| 1932 | Medical development (device) | American cardiac surgeon Michael E. DeBakey develops the roller pump, which later becomes an essential component of the heart-lung machine.[15] | Tulane University, New Orleans |

| 1937 | Medical development (device) | An artificial heart designed by Soviet scientist W. P. Demichow is first successfully applied on a dog for 5.5 hours.[10] | Soviet Union |

| 1938 | Medical development | American surgeon Robert Gross applies systematically the first modern cardiovascular surgery when successfully closes a patent ductus arteriosus.[16] | Boston Children's Hospital, Boston |

| 1941 | Medical development | French physician André Cournand and American physician Dickinson Richards, use the cardiac catheter as a diagnostic tool for the first time, applying catheterization techniques to measure right-heart pressures and cardiac output. Both are awarded the Nobel Prize in 1956.[16][17] | Bellevue Hospital, New York City |

| 1948 | Scientific development | The Framingham Heart Study is initiated under the direction of the National Heart Institute to better understand atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. 1,980 male and 2,421 female volunteers are recruited. The study identifies several factors that put a person at risk for atherosclerosis: among them, high levels of cholesterol. Over 1000 medical papers will have been published related to the Framingham Heart Study.[18][19] | Framingham, Massachusetts |

| 1949 | Medical development (device) | IBM develops the Gibbon Model I heart-lung machine. It consists of DeBakey pumps and film oxygenator.[10] | United States |

| 1949–1958 | Scientific development | Scottish epidemiologist Jerry Morris performs studies on cardiovascular health, later establishing the importance of physical activity in preventing cardiovascular disease.[20] | |

| 1950 | Organization | The First World Congress of Cardiology (WCC) is held.[21] | Paris |

| 1950 | Scientific development | Team led by American scientist John Gofman demonstrates the role of lipoproteins in the causation of heart disease.[18][22] | University of California, Berkeley |

| 1950-1958 | Medical development | Scientists Karl H. Beyer, James M. Sprague, John E. Baer, and Frederick C. Novello of Merck and Co develop thiazides for treatment of hypertension and heart failure. | |

| 1950–1959 | Medical development (drug) | Scottish pharmacologist James Black develops propranolol, a beta blocker used for the treatment of heart disease. Black is awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988 for this work.[16] | Imperial Chemical Industries, London |

| 1950–1959 | Scientific development | American scientist Ancel Keys discovers that heart disease is rare in some Mediterranean populations where fat diet has slow consumption.[2] | Southern Europe |

| 1952 | MEdical development (device) | Swedish cardiologist Inge Edler and German physicist Carl Hellmuth Hertz adapt for human use a sonar device for detecting submarines in World War II and record echoes from the walls of a human heart, thereby launching the field of echocardiography.[16] | |

| 1952 | Medical development (device) | American cardiologist Paul Zoll develops the first external cardiac pacemaker.[16][10] | Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| 1952 | Medical development | American surgeon Charles A. Hufnagel sews an artificial valve into a patient's aorta.[10] | |

| 1953 | Medical development | American surgeon John Gibbon performs the first open-heart operation using cardiopulmonary bypass.[16] | Thomas Jefferson Hospital, Philadelphia |

| 1953 | Dr Michael DeBakey implants a seamless, knit Dacron tube for surgical repairs and/or replacement of occluded vessels of vascular aneurysms.[10] | United States | |

| 1958 | Medical development (drug) | Thiazide diuretics are introduced for treating hypertension.[1] | |

| 1959 | Program | The World Health Organization establishes Cardiovascular Disease program.[23] | |

| 1960 | Scientific development | Framingham Study: Cigarette smoking is found to increase the risk of heart disease.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1960 | Medical development | The first successful coronary artery bypass operation (anastomosis) is performed by German surgeon Robert H. Goetz.[25] | Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City |

| 1961 | Scientific development | Cholesterol level, blood pressure, and electrocardiogram abnormalities are found to increase the risk of heart disease.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1961 | Organization | The British Heart Foundation (BHF) is established as a charity organization in order to fund research on cardiovascular disease.[26] | London |

| 1963 | Organization | Instituto do Coração da Universidade de São Paulo is founded as a center specializing in cardiology, cardiovascular medicine and cardiovascular surgery.[27] | Sao Paulo |

| 1964 | Medical development | Russian cardiac surgeon Vasiliy Kolesov performs the first successful coronary bypass using a standard suture technique.[25] | |

| 1964 | Medical development | American interventional radiologist Charles Dotter describes angioplasty for the first time.[28] | |

| 1967 | Medical development | South African cardiac surgeon Christiaan Barnard performs the first successful human-to-human heart transplant.[1] | Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town |

| 1967 | Medical development | Argentine cardiac surgeon René Favaloro performs the first documented saphenous aortocoronary bypass.[29] | Cleveland Clinic, Ohio |

| 1967 | Dcientific development | Physical inactivity and obesity are found to increase the risk of heart disease.[23] | U.S.A. |

| 1968 | Medical development (device) | A. Kantrowitz et al. perform the first clinical trial in a man with intra-aortic balloon pumping.[10] | |

| 1969 | Organization | The International Cardiology Foundation (ICF) is established.[30] | Geneva |

| 1969 | Medical development (device) | Argentine cardiac surgeon Domingo Liotta and American cardiac surgeon Denton Cooley perform the first clinical implantation of a total artificial heart (TAH).[31] | The Texas Heart Institute, Houston |

| 1970 | Organization | The Sixth World Congress of Cardiology is held. During this congress, the International Cardiology Federation (ICF) is created.[21] | London |

| 1970 | Scientific development | Atrial fibrillation is found to increase stroke risk 5-fold.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1971 | Medical development (device) | White– Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) are implemented on newborn babies using veno-venous bypass for up to 9 days.[10] | |

| 1975 | Organization | The Philippine Heart Center is founded.[32] | Quezón City, Philippines |

| 1976 | Scientific development | Menopause is found to increase the risk of heart disease[24] | U.S.A |

| 1977 | Medical development | German radiologist Andreas Gruentzig first develops coronary angioplasty for treatment of coronary artery disease.[33] | Zurich, Switzerland |

| 1978 | Scientific development | Psychosocial factors are found to affect heart disease.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1978 | Organization | The International Society of Cardiology and the International Cardiology Federation merge to become the International Society and Federation of Cardiology.[21] | |

| 1979 | Organization | The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) is founded as an international non-profit organization in order to promote education and advocacy for cardiac arrhythmia professionals and patients.[34] | Washington, D.C. |

| 1982 | Medical development (device) | The Jarvik 7 total artificial heart, named for its designer, Dr. Robert Jarvik, is implanted in a patient.[35] | University of Utah |

| 1984 | Medical development | American surgeon Leonard L Bailey transplants a baboon heart into Baby Fae, at Loma Linda Medical Center. The baby survives for three weeks.[10] | United States |

| 1984 | Medical development (device) | Oyer and Portner use the Novacor electronically powered implantable left ventricular assist device as the first successful bridge to transplant.[36][10] | |

| 1986 | Medical development (device) | French physician Jacques Puel and German cardiologist Ulrich Sigwart are attributed to be the first to use the coronary stent.[37] | Toulouse, France |

| 1986 | Medical development (device) | The first atherectomy devices that remove material from the vessel wall are introduced.[10] | |

| 1987 | Medical development | Study done by Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS), shows unequivocal survival benefit of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in severe heart failure.[1] | |

| 1988 | Medical development (device) | Hemopump, a temporary left ventricular assist blood pump, is put to clinical use. It is designed to allow for temporary support of a failing heart.[38] | The Texas Heart Institute, Houston |

| 1988 | Medical development (device) | The first successful long-term implantation of an artificial Ventricular assist device LVAD is conducted by Dr. William F. Bernhard.[39] | Boston Children's Hospital |

| 1993 | Organization | the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) is founded.[40] | |

| 1994 | Scientific development | Enlarged left ventricle (one of two lower chambers of the heart) is shown to increase the risk of stroke.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1995 | Publication | The European Society of Cardiology publishes guidelines for diagnosing heart failure.[1] | |

| 1996 | Scientific development | Progression from hypertension to heart failure is described.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1997 | Medical development (device) | The Thoratec Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) is put to clinical use to support patients with acute and chronic heart failure.[41] | The Texas Heart Institute, Houston |

| 1998 | Scientific development | Framingham Study: Atrial fibrillation is found to be associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality.[24] | U.S.A |

| 1998 | Organization | The International Society and Federation of Cardiology board approves the change of name to World Heart Federation (WHF).[21] | |

| 1999 | Scientific development | Lifetime risk at age 40 years of developing coronary heart disease is found to be one in two for men and one in three for women.[24] | U.S.A |

| 2000 | Organization | The World Heart Federation launches World Heart Day as an annual event on the last Sunday of each September.[21] | |

| 2000 | Organization | The Krishna Heart Institute is founded as a high-end medical facility, specializing in heart diseases.[42] | Ahmedabad, India |

| 2000 | Organization | The Blood Pressure Association is founded as a charitable organization to provide information and support to people with hypertension.[43] | London |

| 2001 | Scientific development | High-normal blood pressure is found to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, emphasizing the need to determine whether lowering high-normal blood pressure can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.[24] | U.S.A |

| 2001 | Medical development (device) | AbioCor total artificial heart is implanted in a 59-year-old man. The TAH is developed by company AbioMed.[44] | Jewish Hospital, Louisville, Kentucky |

| 2002 | Medical development | Alain Cribier performs the first percutaneous aortic valve replacement.[10] | |

| 2004 | Scientific development | Serum aldosterone levels are found to predict future risk of hypertension in non-hypertensive individuals.[24][45] | Boston Medical Center, U.S.A |

| 2004 | Medical development | The CardioWest TAH-t becomes the world's first temporary total artificial heart (TAH-t). It is indicated for use as a bridge to transplant in cardiac transplant patients at risk of imminent death from nonreversible biventricular failure.[10] | |

| 2006 | Organization | The Multan Institute of Cardiology is founded.[46] | Multan, Pakistan |

| 2007 | Organization | Atrial Fibrillation Association is established as an international charity that provides information and support for patients with atrial fibrillation.[47] | Shipston-on-Stour, United Kingdom |

| 2008 | Epidemiology | The total number of deaths due to cardiovascular disease reads 17.3 million worldwide a year according to the WHO.[48] | |

| 2008 | Organization | The Sixteenth World Congress of Cardiology is held. From then on, the WCC moves from a 4-year to a 2-year cycle.[21] | Buenos Aires |

| 2010 | Scientific development | Sleep apnea is found to be tied to increased risk of stroke.[24][49] | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Maryland, U.S.A |

| 2011 | Medical development (drug) | pCMV-vegf165 is registered in Russia as the first-in-class gene therapy drug for treatment of peripheral artery disease, including the advanced stage of critical limb ischemia.[50][51] | Russia |

| 2011 | Update | The UN declaration on Non-communicable diseases change the global approach to NCD’s of which cardiovascular disease is the greatest contributor.[21] | |

| 2012 | Epidemiology | Ischemic heart disease and stroke are found to be the leading causes of death worldwide, with 7.4 million deaths due to ischemic heart disease and 6.7 million deaths for stroke.[3] | |

| 2013 | Program | World Heart Federation board adopts the United Nations and World Health Organization targets for cardiovascular disease, launching the 25 x 25 campaign to reduce premature death from CVD by 25% by 2025.[21] |

See also

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 R C Davis, F D R Hobbs, G Y H Lip (2000). "History and epidemiology". BMJ. 320: 39–42. PMC 1117316

. PMID 10617530. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.39.

. PMID 10617530. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.39.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Colleen Story,Kristeen Cherney. "The History of Heart Disease". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The top 10 causes of death". Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular disease". trends.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular disease". books.google.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular disease". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The Evolution of Surgery for the Treatment and Prevention of Stroke". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Lewis, O. (1994-12-01). "Stephen Hales and the measurement of blood pressure". Journal of Human Hypertension. 8 (12): 865–871. ISSN 0950-9240. PMID 7884783.

- ↑ "Description of Angina Pectoris by William Heberden". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 Nawrat, Zbigniew. Handbook of Polymer Applications in Medicine and Medical Devices: 8. Review of Research in Cardiovascular Devices.

- ↑ Bright, Richard (1831). Reports of Medical Cases, Selected with a View of Illustrating the Symptoms and Cure of Diseases by a Reference to Morbid Anatomy, volume I. London: Longmans.

- ↑ "History of the American Heart Association". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Baker". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Werner Forssmann". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "Michael DeBakey". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Eugene Braunwald. "Cardiology: the past, the present, and the future". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 42: 2031–2041. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.025.

- ↑ Nirav J. Mehta, Ijaz A. Khan (2002). "Cardiology's 10 Greatest Discoveries of the 20th Century". Tex Heart Inst J. NCBI. 29: 164–71. PMC 124754

. PMID 12224718.

. PMID 12224718.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "A History of Heart Disease Treatment". Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Framingham Heart Study". Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ Ashton JR (2000). "Professor J N "Jerry" Morris". J Epidemiol Comm Health. 54: 881a. doi:10.1136/jech.54.12.881a.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 "World Heart Federation". Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "John Gofman". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "who cardiovascular diseases" (PDF). Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 "Research Milestones". Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Jordan D. Haller, Andrew S. Olearchyk (2002). "Cardiology's 10 Greatest Discoveries". Tex Heart Inst J. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 29: 342–4. PMC 140304

. PMID 12484626.

. PMID 12484626.

- ↑ "British Heart Foundation". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "incor". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Dotter CT, Judkins MP (November 1964). "Transluminal treatment of arteriosclerotic obstruction". Circulation. 30 (5): 654–70. PMID 14226164. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.30.5.654.

- ↑ Denton A. Cooley (2000). "In Memoriam: Tribute to René Favaloro, Pioneer of Coronary Bypass". Tex Heart Inst J. 27: 231–2. PMC 101069

. PMID 11225585.

. PMID 11225585.

- ↑ "The International Society of Cardiology (ISC) and CVD Epidemiology". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ↑ "Professor Domingo Santo Liotta". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "Philippine Heart Center". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Bernhard Meier, Dölf Bachmann, Thomas F Lüscher (February 2003). "25 years of coronary angioplasty: almost a fairy tale". The Lancet. 361: 527. PMID 12583964. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12470-1.

- ↑ "Heart Rhythm Society". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Jarvik 7". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Textbook of Organ Transplantation Set (Allan D. Kirk, Stuart J. Knechtle, Christian P. Larsen, Joren C. Madsen, Thomas C. Pearson, Steven A. Webber ed.).

- ↑ Roguin, Ariel (2011). "Historical Perspectives in Cardiology". Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventsions. 4 (2): 206–209. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.960872.

- ↑ "Hemopump". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "LVAD". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "ASNC". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Thoratec VAD". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Krishna Heart Institute". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Blood Pressure Association". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "AbioCor". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Ramachandran S. Vasan, M.D., Jane C. Evans, D.Sc., Martin G. Larson, Sc.D., Peter W.F. Wilson, M.D., James B. Meigs, M.D., M.P.H., Nader Rifai, Ph.D., Emelia J. Benjamin, M.D., Daniel Levy, M.D. "Serum Aldosterone and the Incidence of Hypertension in Nonhypertensive Persons". New England Journal of Medicine. 351: 33–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa033263.

- ↑ "Multan Institute of Cardiology". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Atrial Fibrillation Association". Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Deaths due to cardiovascular disease". Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Sleep apnea tied to increased risk of stroke". Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Gene Therapy for PAD Approved". 6 December 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Deev, R.; Bozo, I.; Mzhavanadze, N.; Voronov, D.; Gavrilenko, A.; Chervyakov, Yu.; Staroverov, I.; Kalinin, R.; Shvalb, P.; Isaev, A. (13 March 2015). "pCMV-vegf165 Intramuscular Gene Transfer is an Effective Method of Treatment for Patients With Chronic Lower Limb Ischemia". Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 20: 473–82. PMID 25770117. doi:10.1177/1074248415574336. Retrieved 28 July 2016.