Timeline of psychiatry

This is a timeline of psychiatry, attempting to describe significant events in the development of the field. Some events related to the development of psychoanalysis are mentioned for historical perspective.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Ancient history | Specialty in psychiatry can be traced in Ancient India, with the oldest texts on psychiatry including the ayurvedic text, Charaka Samhita.[1][2] Some of the first hospitals for curing mental illness are established during the 3rd century BCE.[3] |

| <18 century | Until the 18th century, mental illness is most often seen as demonic possession. However, it gradually comes to be considered as a sickness requiring treatment. Many judge that modern psychiatry is born with the efforts of French physician Philippe Pinel in the late century.[4] |

| 19th century | Psychiatry gets its name as a medical specialty in the early 1800s. For the first century of its existence, the field concerns itself with severely disordered individuals confined to asylums or hospitals. These patients are generally psychotic, severely depressed or manic, or suffer conditions we would now recognize as medical: dementia, brain tumors, seizures, hypothyroidism, etc.[5] Research and teaching in psychiatry are dominated by the Germans for 100 years, until 1933.[6] Great contributions to the field occur in the late 19th century, when German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin emphasizes a systematic approach to psychiatric diagnosis and classification and Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who is familiar with neuropathology, develops psychoanalysis as a treatment and research approach.[4] |

| 20th century | Around the turn of the century, Sigmund Freud publishes theories on the unconscious roots of some of these less severe disorders, which he terms psycho-neuroses. Psychoanalysis is the dominant paradigm in outpatient psychiatry for the first half of the century. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, new medications begin to change the face of psychiatry.[5] The modern era of clinical neuropsychiatry begins likely around the 1980s.[7] Second-generation antipsychotics are introduced into clinical psychiatry in the early 1990s.[8] |

| 21st century | Pharmaceutical innovation dries up in the 2000s, with no new classes of medication or blockbuster psychiatric drugs being discovered.[5] |

Numerical and visual data

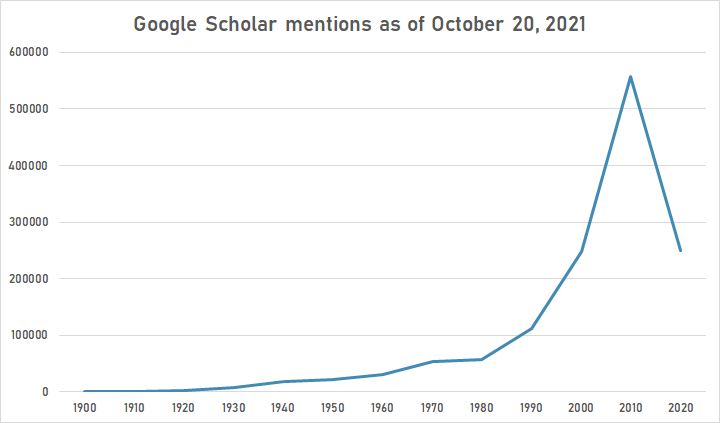

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of October 20, 2021.

| Year | psychiatry |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 946 |

| 1910 | 982 |

| 1920 | 1,210 |

| 1930 | 1,930 |

| 1940 | 2,340 |

| 1950 | 4,600 |

| 1960 | 8,260 |

| 1970 | 14,500 |

| 1980 | 29,900 |

| 1990 | 68,600 |

| 2000 | 204,000 |

| 2010 | 595,000 |

| 2020 | 170,000 |

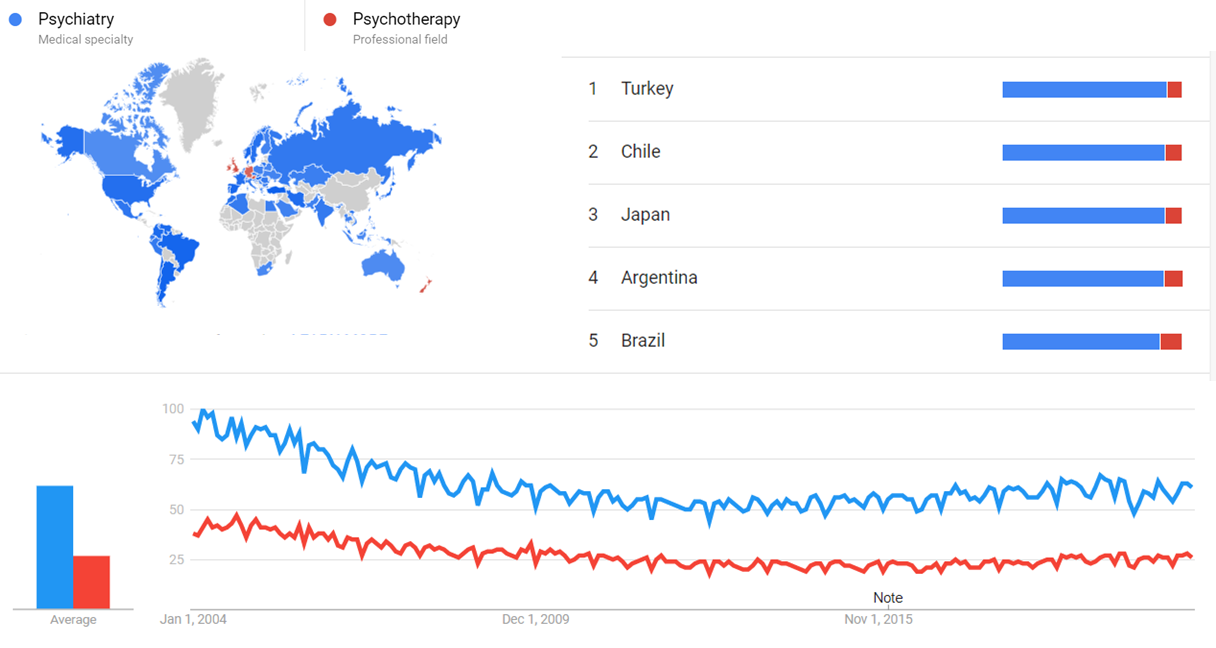

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data Psychiatry (Medical specialty) and Psychotherapy (Professional field) from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[9]

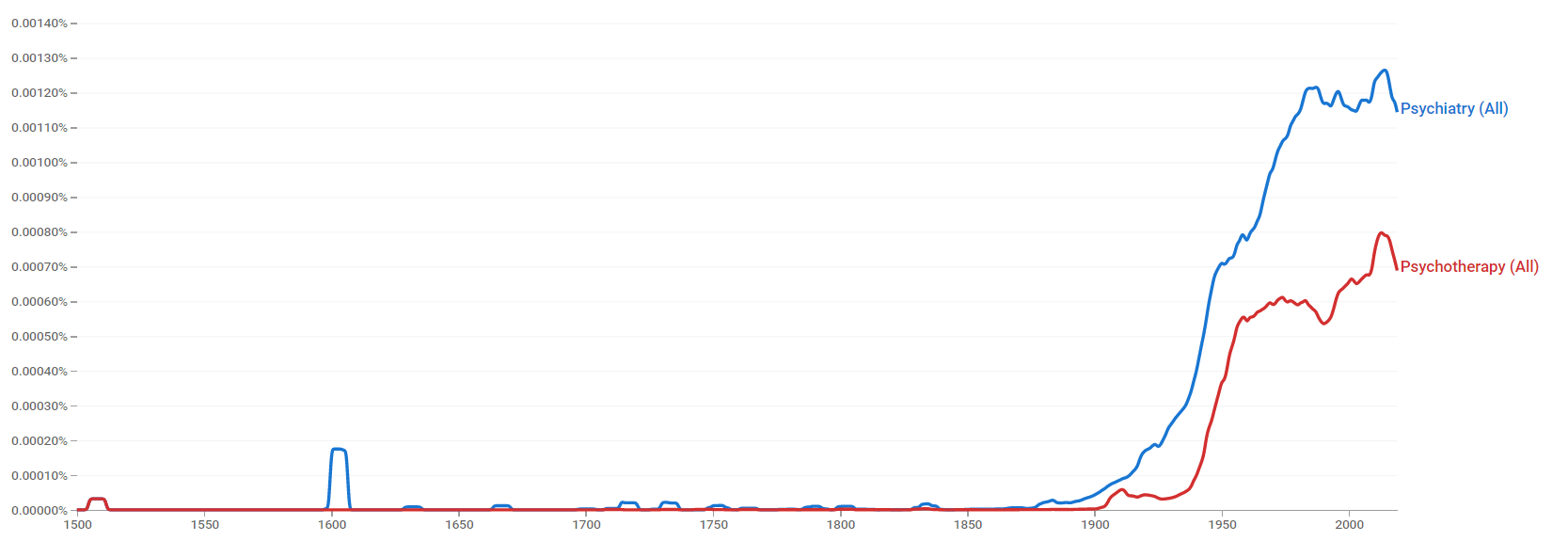

Google Ngram Viewer

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy from 1500 to 2019. [10]

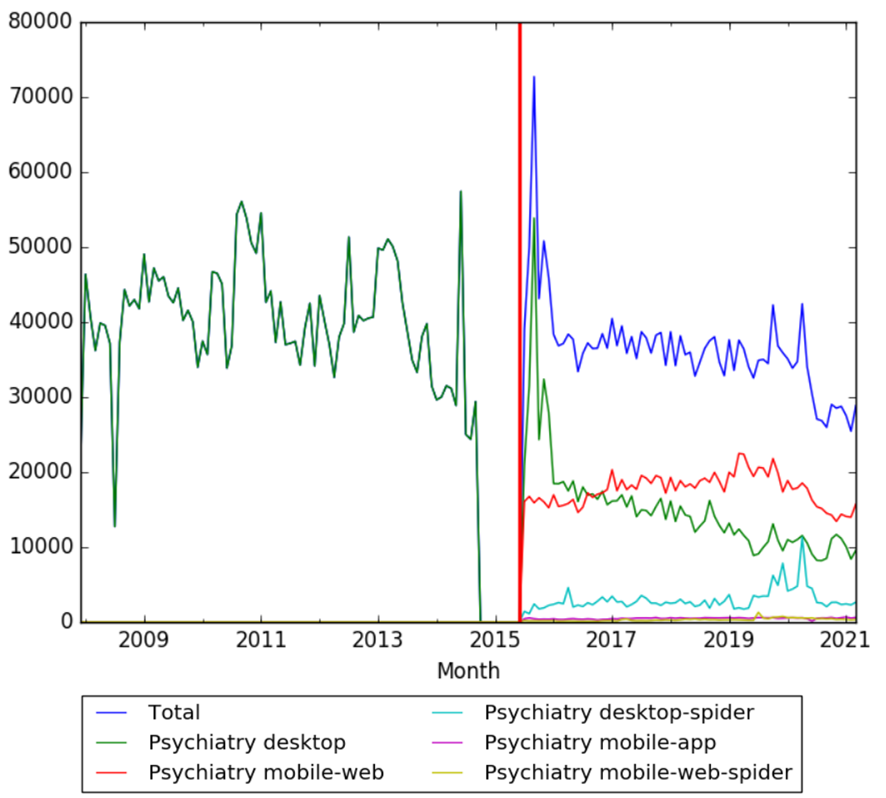

Wikipedia views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Psychiatry, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to March 2021. The data gap observed from October 2014 to June 2015 is the result of Wikipedia Views failure to retrieve data.[11]

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1656 | Facility | Louis XIV of France establishes the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris for prostitutes and the mentally defective.[12] | France |

| 1672 | Literature | English physician Thomas Willis publishes the anatomical treatise De Anima Brutorum, describing psychology in terms of brain function. | Unied Kingdom |

| 1724 | Field development | New England Puritan minister Cotton Mather breaks with superstition by advancing physical explanations for mental illnesses over demonic explanations.[13] | United States |

| 1758 | Literature | English physician William Battie publishes Treatise on Madness, likely the first English medical monograph devoted to madness.[14] | United Kingdom |

| 1793 | Field development | French physician Philippe Pinel in Paris begins what is then called “moral treatment and occupation”, as an approach to treating people with mental illness. Pinel believes that moral treatment means treating one’s emotions. Treatment for the mentally ill thus becomes based on purposeful daily activities. Pinel begins advocating for, and using, literature, music, physical exercise, and work as a way to “heal” emotional stress, thereby improving one’s ability to perform activities of daily living.[15] | France |

| 1808 – 1816 | Field development | German physician Johann Christian Reil coins the term psychiatry.[16][17][18][6] | Germany |

| 1809 | Field development | Philippe Pinel publishes the first description of dementia praecox (schizophrenia).[19][20][21] | France |

| 1811 | Field development | German physician Johann Christian August Heinroth in Leipzig occupies the first chair of psychiatry/psychotherapy in the Western world.[22] | Germany |

| 1812 | Literature | American physician Benjamin Rush publishes Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon Diseases of the Mind, which would become very influencial in the field of psychiatry for the next 70 years.[23][24] | United States |

| 1822 | Field development | French physician Antoine-Laurent Bayle attributes the psychiatric symptoms of neurosyphilis to a chronic inflammation of the meninges, making him the first person to discover a psychiatric disease with definite organicity.[22] | |

| 1834 | Facility | American philantropist Anna Marsh deeds the funds to build the first financially-stable private asylum in the United States. The Brattleboro Retreat marks the beginning of America’s private psychiatric hospitals challenging state institutions for patients, funding, and influence.[22] | United States |

| 1838 | Field development | France passes a law that establishes its modern asylum system. Other countries like England, Germany, and the United States quickly follow suit.[22] | France |

| 1841 | Facility | The Association of Medical Officers of Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane is founded in England.[25][26] | United Kingdom |

| 1844 | Organization | The Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII) is founded in Philadelphia.[27] | United States |

| 1845 | Policy | The Lunacy Act 1845 is passed in Britain. It is the first British statute to treat the insane as “persons of unsound mind” rather than social outcasts.[28] | United Kingdom |

| 1852 | Literature | French physician Bénédict Augustin Morel publishes Traite des Maladies Mentales, which introduces the term "dementia praecox".[29][30] | France |

| 1852 | Field development | French physician Charles Lasègue first describes paranoid dementia as "delusion of persecution".[29] | France |

| 1857 | Literature | Bénédict Augustin Morel publishes Traité des Dégénérescences, which is considered a foundational text of the degeneration theory.[31][32][33] | France |

| 1859 | Literature | French physician Paul Briquet publishes Traite Clinique et Therapeutique de L'Hysterie, which presents 430 cases of hysterical patients at the Hôpital de la Charité in Paris.[34][35][36] | France |

| 1885 | Drug | Sulfonethylmethane (Trional), a hypnosedative prepared by condensing ethylmercaptan with metyl ethyl ketone, is synthesized by Bayer.[37] | Germany |

| 1888 | Field development | Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt performs the first attempts at psychosurgery. Six chronic schizophrenic patients undergo localized cerebral cortical excisions. Most patients show improvement and become easier to manage, although one dies from the procedure and several have aphasia or seizures.[22] | Switzerland |

| 1893 | Field development | German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin introduces the concept of "dementia praecox", later reformulated as schizophrenia.[38][39] | Germany |

| 1895 | Literature | Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer publish Studies on Hysteria, based on the case of Bertha Pappenheim.[40][41][42] | Austria |

| 1900 | Field development | Russian neurologist Vladimir Bekhterev discovers the involvement of the hippocampus in memory.[43][44][45] | Russia |

| 1901 | Field development | German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer identifies the first case of what would later become known as Alzheimer's disease.[46][47][48] | Germany |

| 1901 | Literature | Sigmund Freud publishes The Psychopathology of Everyday Life.[49] | |

| 1905 | Field development | French psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon develop the Binet-Simon Scale as a means to determine the children in need of alternative education.[50][51][52] | |

| 1906 | Field development | Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov publishes the first studies in classical conditioning.[53][54] | Russia |

| 1908 | Field development | Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler introduces the term Schizophrenia.[29] | |

| 1911 | Organization | The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) is founded.[55] | United States |

| 1913 | Organization | The British Psychoanalytical Society is founded by Ernest Jones.[56] | United Kingdom |

| 1920 | Field development | Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach develops the Rorschach Inkblot Test.[57] | |

| 1923 | Field development | English neuroscientist Sir Henry Dale finds that acetylcholine can mimic the effect of the parasympathetic system.[58][59][60] | |

| 1924 | Field development | German neuropsychiatrist Hans Berger first describes Electroencephalography (EEG).[61][62][63] | Germany |

| 1924 | Literature | Austrian psychoanalyst Otto Rank publishes The Trauma of Birth, coining the term "pre-Oedipal".[64] | |

| 1926 | Organization | La Société Psychanalytique de Paris was founded.[65] | |

| 1927 | Field development | Austrian-Jewish neurophysiologist Manfred Sakel in Vienna develops Insulin Shock Therapy as a treatment for schizophrenia.[66] | Austria |

| 1928 | Organization | The Indian Association for Mental Hygiene is established.[67][68] | India |

| 1938 | Field development | Italian neurologist Ugo Cerletti and Italian psychiatrist Dr. Lucio Bini discover electroconvulsive Therapy.[69][70][71] | Italy |

| 1939 | Literature | Russian-born researcher Nathaniel Kleitman publishes Sleep and Wakefulness.[72] | |

| 1943 | Drug | Methamphetamine (Desoxyn), a member of the amphetamine class, is marketed by Abbot Laboratories.[37] | |

| 1944 | Drug | Ritalin (Methylphenidate) is first synthesized.[73][74][75] | |

| 1947 | Organization | The Indian Psychiatric Society is established.[76][77][78] | India |

| 1948 | Field development | Australian psychiatrist John Cade discovers that lithium is dramatically effective in the treatment of mania.[79][80][81] | Australia |

| 1949 | Field development | Portuguese neurologist Antonio Moniz is awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on Lobotomy.[82] | |

| 1949 | Literature | The World Health Organization publishes ICD-6, the sixth revision of the International statistical classification of diseases, which includes a section on mental disorders for the first time.[83] | |

| 1950s | Field development | American psychologist Albert Ellis develops Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT).[84] | United States |

| 1950 | Organization | The World Psychiatric Association is founded.[85][86][87] | |

| 1951 | Drug | Methylparafynol (methilpentynol; meparfynol), an early tranquilizer and member of the carbinol drug class, is introduced.[37] | |

| 1952 | Field development | The American Psychiatric Association publishes the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.[88][89][90] | United States |

| 1952 | Drug | The first monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) antidepressant iproniazid is discovered.[91][92][93] | |

| 1952 | Field development | French psychiatrist Jean Delay becomes the first to recognize the therapeutic value of chlorpromazine in the treatment of schizophrenia. He invents the word psychopharmacology.[22] | France |

| 1952 | Drug | Phenothiazine antipsychotic mepazine is synthesized in Germany.[37] | Germany |

| 1953 | Field development | Nathaniel Kleitman, at the University of Chicago, discoveres Rapid eye movement sleep (REM), founding modern sleep research.[72][94][95] | United States |

| 1953 | Drug | Chlorpromazine, a “mood-calming” drug, is licensed in the United States.[22] | United States |

| 1954 | Field development | James Olds and Peter Milner of McGill University discover the brain reward system.[96][97][98][99] | Canada |

| 1954 | Field development | American neurobiologist Roger Sperry begins split-brain research at the Californian Institute of Technology.[100][101][102] | United States |

| 1954 | Organization | All India Institute of Mental Health is founded.[103][104] | India |

| 1955 | Drug | Ethinamate (Valmid), a hypnosedative of the carbmate class, is launched.[37] | |

| 1955 | Field development | The term neuroleptic is coined to refer to the effects of phenothianzine medication. It becomes a synonym for antipsychotic.[37] | |

| 1955 | Drug | Meprobamate (Miltown), an antineurotic drug of the dicarbamate class, is marketed.[37] | |

| 1955 | Drug | Methyprylon (Nodular), a hypnosedative of the piperidine class, is launched by Hoffmann-La Roche.[37] | |

| 1955 | Drug | Talbutal (Lotusate), a barbiturate sedative, is marketed.[37] | |

| 1956 | Drug | Heterocyclic tranquilizer mephenoxalone is introduced in Argentina. In 1961, it is introduced in the United States.[37] | Argentina |

| 1956 | Field development | Gregory Bateson, John Weakland, Donald deAvila Jackson, and Jay Haley propose the double bind theory of schizophrenia's thought disorder.[105][106][107] | |

| 1957 | Field development | Swedish neuropharmacologist Arvid Carlsson, at the University of Lund, discovers that dopamine is one of the brain chemicals used to send signals between neurons.[108][109][110] | Sweden |

| 1957 | Drug | Imipramine hydrochloride (tofranil) becomes available as the first of a series of new anti-depressive drugs.[111][112][113] | |

| 1958 | Drug | Oxanamide (Quiatcin), a tranquilizer, is introduced.[37] | |

| 1958 | Field development | American physician Aaron B. Lerner at Yale University first isolates the hormone melatonin, which is found to regulate the circadian rhythm.[114][115][116][117] | United States |

| 1959 | Journal | The Archives of General Psychiatry is established by the American Medical Association.[118] | United States |

| 1959 | Drug | Nialamide (Niamid) is launched by Pfitzer for depression.[37] | |

| 1960s | Field development | Aaron T. Beck develops cognitive therapy.[119][84] | |

| 1960 | Drug | The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide, under the trade name Librium is introduced.[120][121][122] | |

| 1961 | Literature | French philosopher Michel Foucault publishes Madness and Civilization, which reflects the growing counter-cultural backlash against psychiatry. Foucault is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, most notably psychiatry, medicine, the human sciences, and the prison system, as well as for his work on the history of human sexuality.[22] | France |

| 1961 | Field development | Canadian psychiatrist Heinz Lehmann coins the term antipsychotic for a drug against psychosis.[37] | |

| 1962 | Drug | Valproate is first approved as an antiepileptic drug.[123] | |

| 1963 | Drug | Nortriptyline (Aventyl), a tricyclic antidepressant that is an active metabolite of amitriptyline, is introduced in the United Kingdom.[37] | United Kingdom |

| 1964 | Drug | Tranquilizer clonazepam is initially patented.[124] | |

| 1965 | Drug | Hypnotic temazepam is patented.[125] | |

| 1966 | Drug | Trazodone (Desyrel) is developed in Italy. It is considered the first of the second-generation antidepressants.[8] | Italy |

| 1967 | Drug | Thiothixine (Navane), an antipsychotic of the thioxanthene series, is introduced.[37] | |

| 1968 | Drug | Carbamazepine is approved for use in the United States for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.[8] | United States |

| 1969 | Drug | Indian-born American organic chemist Nariman Mehta invents organic compound bupropion in the hopes of developing a superior antidepressant with abilities to treat various psychiatric disorders.[126] | |

| 1971 | Field development | Computed axial tomography (CAT scans) begins to show the living brain in greater detail than ever before, allowing psychiatrists a way to view the subtleties of the brain without surgery.[22] | |

| 1972 | Field development | American psychologist David Rosenhan publishes the Rosenhan experiment, a comparative study of validity of psychiatric diagnosis.[127][128][129] | United States |

| 1973 | Field development | The American Psychiatric Association declassifies homosexuality as a mental disorder.[130][131][132] | United States |

| 1973 | Drug | Tetracyclic antidepressant maprotiline (Ludiomil) is introduced in Germany.[37] | Germany |

| 1974 | Drug | Atypical antipsychotics clozapine (Clozaril), is introduced in Germany.[37] | Germany |

| 1975 | Drug | Mianserin (Tolvin), a tetracyclic antidepressant, is introduced in Germany.[37] | Germany |

| 1976 | Drug | Nomifensine (Alival), a bicyclic antidepressant, is introduced by Hoechst in Germany.[37] | Germany |

| 1977 | Drug | Lorazepam (Ativan) is introduced in the United States for anxiety, efficacy, and catatonia.[37] | United States |

| 1980 | Literature | The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, III) is published by the {w{w|American Psychiatric Association}}. Considered the psychiatry’s “bible,” it marks the shift in clinical psychiatry from a largely Freudian approach to a more biological orientation.[22] | United States |

| 1980 | Field development | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a diagnosis is coined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Third Edition (DSM, III) as attention deficit disorder (ADD).[37] | United States |

| 1981 | Drug | Zimelidine (Zelmid), the first SSRI antidepressant, is launched in Europe.[37] | Europe |

| 1982 | Program | The National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) is launched in India, in order to improve the mental health care infrastructure in the country.[133][134] | India |

| 1980 | Drug | Amoxapine (Asendin), a tricyclic antidepressant with neuroleptic properties, is launched.[37] | |

| 1983 | Organization | The European Psychiatric Association is founded.[135] | France |

| 1986 | Organization | The American Psychiatric Nurses Association is founded.[136] | United States |

| 1987 | Drug | Antidepressant Prozac is released.[5] | |

| 1987 | Organization | The British Neuropsychiatry Association is established. It is the oldest in the world.[137] | United Kingdom |

| 1988 | Organization | The American Neuropsychiatric Association is founded.[7][137] | United States |

| 1990s | The United States National Institute of Mental Health declares the 1990s the Decade of the Brain "to enhance public awareness of the benefits to be derived from brain research."[5] | United States | |

| 1990 | Field development | Japanese researcher Seiji Ogawa first discovers blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) in MRI. [138] | |

| 1991 | Drug | Anticonvulsant lamotrigine is first introduced in Ireland.[139] | Ireland |

| 1991 | Field development | Hong Kong-born American scientist Kenneth Kwong successfully applies blood-oxygen-level dependent imaging (BOLD) to image human brain activities with MRI.[140] | United States |

| 1991 | Drug | Antidepressant sertraline is first approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration.[141] | United States |

| 1992 | Drug | Antidepressant paroxetine is first marketed in the United States.[142] | United States |

| 1993 | Drug | Antidepressant venlafaxine is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration.[143] | United States |

| 1994 | Field development | American molecular geneticist Jeffrey M. Friedman and team report the long-sought identity and function of leptin, a key fat-derived hormone that regulates feeding behaviour and body weight.[144][145] | United States |

| 1995 | Drug | Antidepressant Mirtazapine (Remeron) is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of depression.[8] | |

| 1996 | Organization | The Japanese Neuropsychiatric Association is founded.[7] | Japan |

| 1998 | Drug | Citalopram is approved for the treatment of depression.[146] | United States |

| 1998 | Organization | The International Neuropsychiatric Association (INA) is formed.[7] | |

| 2002 | Organization | The European Brain Council is founded in Brussels.[147][148] | Belgium |

| 2001 | Drug | Ziprasidone (Geodon), an atypical antipsychotic, is marketed.[37] | |

| 2002 | Drug | Escitalopram is introduced for treatment of depression and anxiety disorders.[149] | |

| 2002 | Organization | The Argentinian Neuropsychiatric Organization is established.[137] | Argentina |

| 2004 | Drug | Duloxetine (sold under the brand name Cymbalta among others) is first used to treat major depressive disorder.[150] | |

| 2007 | Legal | global pharmaceutical Eli Lilly and Company agrees to pay up to US$500 million to settle 18,000 lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa.[22] | United States |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Andrew Scull. Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness: An A-to-Z Guide, Volume 1. Sage Publications. p. 386.

- ↑ David Levinson; Laura Gaccione (1997). Health and Illness: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 42.

- ↑ Koenig, Harold G. (2009). Faith and Mental Health: Religious Resources for Healing. Templeton Foundation Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-59947-078-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Psychiatry". britannica.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "A brief history of psychiatry". stevenreidbordmd.com. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac". ps.psychiatryonline.org. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Mula, Marco. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Epilepsy.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Sadock, Benjamin J.; Sadock, Virginia A.; Ruiz, Pedro. Kaplan & Sadock's Study Guide and Self-Examination Review in Psychiatry.

- ↑ "Psychiatry and Psychotherapy". Google Trends. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ "Psychiatry and Psychotherapy". books.google.com. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ "Psychiatry". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ Caravantes, Peggy. The Many Faces of Josephine Baker: Dancer, Singer, Activist, Spy.

- ↑ Thompson, Marie L. Mental Illness.

- ↑ "William Battie's Treatise on Madness (1758)" (PDF). cambridge.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "History of Occupational Therapy". otnz.co.nz. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac". gun-violence.psychiatryonline.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "From Madness to Mental Illness: History of Psychiatry 101". hystera.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "Psychoanalysis". creativechess.wordpress.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Turner, Francis J. Adult Psychopathology, Second Edition: A Social Work Perspective.

- ↑ Shults, Sylvia. Tales from the Asylum.

- ↑ Shults, Sylvia. 44 Years in Darkness: A True Story of Madness, Tragedy, and Shattered Love.

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 "20 Major Milestones in Psychiatric History". howtobecomeapsychiatrist.org. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Neukrug, Edward S. The World of the Counselor: An Introduction to the Counseling Profession.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Special Education, Volume 4: A Reference for the Education of Children, Adolescents, and Adults Disabilities and Other Exceptional Individuals (Cecil R. Reynolds, Kimberly J. Vannest, Elaine Fletcher-Janzen ed.).

- ↑ Bewley, Thomas. Madness to Mental Illness: A History of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- ↑ Shepherd, Anna. Institutionalizing the Insane in Nineteenth-Century England.

- ↑ Goodheart, Lawrence. ""The Glamour of Arabic Numbers": Pliny Earle's Challenge to Nineteenth-Century Psychiatry". PMC 4887602

. PMID 26232441.

. PMID 26232441.

- ↑ "Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th earl of Shaftesbury". britannica.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Literary Medicine: Brain Disease and Doctors in Novels, Theater, and Film (J. Bogousslavsky, S. Dieguez ed.).

- ↑ Noll, Richard. The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders.

- ↑ Foerster, Maxime. The Politics of Love: Queer Heterosexuality in Nineteenth-Century French Literature.

- ↑ Heredity and Infection: The History of Disease Transmission (Jean-Paul Gaudilliére, Ilana Löwy ed.).

- ↑ Schuster, Jean‐Pierre; Le Strat, Yann; Krichevski, Violetta; Bardikoff, Nicole; Limosin, Frédéric. "Benedict Augustin Morel (1809–1873)".

- ↑ Massicotte, Claudie. Trance Speakers: Femininity and Authorship in Spiritual Séances, 1850-1930.

- ↑ Hysteria: The Rise of an Enigma (J. Bogousslavsky ed.).

- ↑ "Psychosomatic Medicine: 'The Puzzling Leap'". nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ 37.00 37.01 37.02 37.03 37.04 37.05 37.06 37.07 37.08 37.09 37.10 37.11 37.12 37.13 37.14 37.15 37.16 37.17 37.18 37.19 37.20 37.21 37.22 37.23 Shorter, Edward. Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward; Fink, Max. The Madness of Fear: A History of Catatonia.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward. A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry.

- ↑ Hergenhahn, B. R. An Introduction to the History of Psychology.

- ↑ Froula, Christine. Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Avant-garde: War, Civilization, Modernity.

- ↑ Bogousslavsky, J. Hysteria: The Rise of an Enigma.

- ↑ Packer, Sharon. Neuroscience in Science Fiction Films.

- ↑ Aggleton, John P. "Looking beyond the hippocampus: old and new neurological targets for understanding memory disorders". PMC 4046414

. PMID 24850926.

. PMID 24850926.

- ↑ "Vladimir Bekhterev, Soviet physiologist". sciencephoto.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Pharmacological Mechanisms in Alzheimer's Therapeutics (A. Claudio Cuello ed.).

- ↑ Akbar, Celestina. Alzheimer's Disease: a Growing Health Care Issue Among the Elderly.

- ↑ "Alois Alzheimer Biography". biography.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, 1901 by Freud". sigmundfreud.net. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Pfeiffer, Steven I. Handbook of Giftedness in Children: Psychoeducational Theory, Research, and Best Practices.

- ↑ Plotnik, Rod; Kouyoumdjian, Haig. Introduction to Psychology.

- ↑ Roeckelein, Jon E. Dictionary of Theories, Laws, and Concepts in Psychology.

- ↑ Coon, Dennis; Mitterer, John. Psychology: A Journey.

- ↑ "Psychology - 1". quizlet.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "American Psychoanalytic Association". apsa.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Biographical Dictionary of Psychology (Noel Sheehy, Antony J. Chapman, Wenday A. Conroy ed.).

- ↑ Fernandez-Ballesteros, Rocio. Encyclopedia of Psychological Assessment.

- ↑ Erling, Norrby. Nobel Prizes And Notable Discoveries.

- ↑ Kudo, Takashi; Davis, Kenneth L.; Blesa Gonzalez, Rafael; Wilkinson, David George. Practical Pharmacology for Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ↑ Velpandian, Thirumurthy. Pharmacology of Ocular Therapeutics.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience.

- ↑ Libenson, Mark H. Practical Approach to Electroencephalography E-Book.

- ↑ Luders, Hans O. Textbook of Epilepsy Surgery.

- ↑ Rank, Otto. The Trauma of Birth.

- ↑ "Brève histoire de la Société Psychanalytique de Paris". spp.asso.fr. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Manfred J. Sakel". cerebromente.org.br. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Hartnack, Christiane. Psychoanalysis in Colonial India.

- ↑ Cross, Wilbur Lucius. Twenty-five Years After: Sidelights on the Mental Hygiene Movement and Its Founder.

- ↑ Kapur, Narinder. The Paradoxical Brain.

- ↑ Coffey, C. Edward. The Clinical Science of Electroconvulsive Therapy.

- ↑ Weiss, Alan. The Electroconvulsive Therapy Workbook: Clinical Applications.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Kohler, William C.; Kurz, Peter J. Hypnosis in the Management of Sleep Disorders.

- ↑ Bergey, Meredith R.; Filipe, Angela M.; Conrad, Peter; Singh, Ilina. Global Perspectives on ADHD: Social Dimensions of Diagnosis and Treatment in Sixteen Countries.

- ↑ "Dr Matthew Smith on ADHD and Ritalin". ewds.strath.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Ritalin". cesar.umd.edu. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Ghodse, Hamid. International Perspectives on Mental Health.

- ↑ Basavanthappa, BT. Essentials of Mental Health Nursing.

- ↑ MHD. Mental Health Digest. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1969.

- ↑ Johnson, F.N. Handbook of Lithium Therapy.

- ↑ Johnson, Frederick Neil. The History of Lithium Therapy.

- ↑ Bryant, Bronwen Jean; Knights, Kathleen Mary. Pharmacology for Health Professionals.

- ↑ Kaku, Michio. The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind.

- ↑ Feinstein, Adam. A History of Autism: Conversations with the Pioneers.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy". simplypsychology.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Okpaku, Samuel O. Essentials of Global Mental Health.

- ↑ Wengell, Douglas; Gabriel, Nathen. Educational Opportunities in Integrative Medicine: The A to Z Healing Arts Guide and Professional Resource Directory.

- ↑ Principles of Addiction Medicine (Richard K. Ries, Shannon C. Miller, David A. Fiellin ed.).

- ↑ Fisher, Gary L.; Roget, Nancy A. Encyclopedia of Substance Abuse Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery.

- ↑ Miller, Leslie A.; McIntire, Sandra A.; Lovler, Robert L. Foundations of Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach.

- ↑ Joseph, Stephen. What Doesn't Kill Us: A guide to overcoming adversity and moving forward.

- ↑ Krishnamurthy, Kalayya. Pioneers in scientific discoveries.

- ↑ Advances in Pharmacology and Chemotherapy.

- ↑ Baldessarini, Ross J. Chemotherapy in Psychiatry: Principles and Practice.

- ↑ Doidge, Mark. Atlas of the Electrical Generators of Sleep.

- ↑ Kryger, Meir H.; Roth, Thomas; Dement, William C. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine E-Book.

- ↑ "Olds & Milner, 1954: "reward centers" in the brain and lessons for modern neuroscience". stanford.edu. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "The Neuroscience of Pleasure and Addiction". psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Rubens, Jim; Rubens, James M. OverSuccess: Healing the American Obsession with Wealth, Fame, Power, and Perfection.

- ↑ Zaidel, Dahlia W. Neuropsychology of Art: Neurological, Cognitive, and Evolutionary Perspectives.

- ↑ Nursing Mirror, Volume 155, Issues 1-13.

- ↑ Carter, Rita. The Human Brain Book.

- ↑ Sperry, Roger Wolcott; Trevarthern, Colwyn B. Brain Circuits and Functions of the Mind: Essays in Honor of Roger Wolcott Sperry, Author.

- ↑ Goldberg, David; Graham, Thornicroft. Mental Health In Our Future Cities.

- ↑ Blank, Leonard; David, Henry Philip. Sourcebook for Training in Clinical Psychology.

- ↑ Noll, Richard. The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders.

- ↑ Packer, Sharon. Neuroscience in Science Fiction Films.

- ↑ Haley, Jay. Leaving Home: The Therapy Of Disturbed Young People.

- ↑ Yeragani, Vikram K.; Tancer, Manuel; Chokka, Pratap; Baker, Glen B. "Arvid Carlsson, and the story of dopamine".

- ↑ Doidge, Norman. The Brain's Way of Healing: Remarkable Discoveries and Recoveries from the Frontiers of Neuroplasticity.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael. A Brief History of Disease, Science, and Medicine: From the Ice Age to the Genome Project.

- ↑ Watts, C. A. H. Depressive Disorders in the Community.

- ↑ Schlaepfer, Thomas E; Nemeroff, Charles B. Neurobiology of Psychiatric Disorders.

- ↑ Schulz, Volker; Hänsel, Rudolf; Blumenthal, Mark; Tyler, V. E. Rational Phytotherapy: A Reference Guide for Physicians and Pharmacists.

- ↑ "Aaron Lerner, Skin Expert Who Led Melatonin Discovery, Dies at 86". nytimes.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Evered, David; Clark, Sarah. Photoperiodism, Melatonin and the Pineal.

- ↑ Melatonin: Therapeutic Value and Neuroprotection (Venkatramanujan Srinivasan, Gabriella Gobbi, Samuel D. Shillcutt, Sibel Suzen ed.).

- ↑ Communication in Plants: Neuronal Aspects of Plant Life (František Baluška, Stefano Mancuso, Dieter Volkmann ed.).

- ↑ Cole, Jim; Stankus, Tony. Journals of the Century.

- ↑ "HISTORY OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY". beckinstitute.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Lajtha, Abel. Alterations of Metabolites in the Nervous System.

- ↑ Merkel, Reinhard; Boer, G.; Fegert, J.; Galert, T.; Hartmann, D.; Nuttin, B.; Rosahl, S. Intervening in the Brain: Changing Psyche and Society.

- ↑ Lane, Dannii. Arachne's Daughter: A Tale of Murder, Mayhem and Madness.

- ↑ Brugger, F; Bhatia, KP; Besag, FM. "Valproate-Associated Parkinsonism: A Critical Review of the Literature.". PMID 27255404. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0341-8.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward (2005). "B". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190292010. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward (2005). "B". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190292010.

- ↑ Fayyazi Bordbar, Mohammad Reza; Jafarzadeh, Morteza. "Bupropion-Induced Diplopia in an Iranian Patient". PMC 3939961

. PMID 24644459.

. PMID 24644459.

- ↑ Wengell, Douglas; Gabriel, Nathen. Educational Opportunities in Integrative Medicine: The A to Z Healing Arts Guide and Professional Resource Directory.

- ↑ Fadul, Jose A. Encyclopedia of Theory & Practice in Psychotherapy & Counseling.

- ↑ Monchinski, Tony. Critical Pedagogy and the Everyday Classroom.

- ↑ Keen, Lisa Melinda; Goldberg, Suzanne Beth. Strangers to the Law: Gay People on Trial.

- ↑ Stern, Phyllis N. Lesbian Health: What Are The Issues?.

- ↑ Díez, Jordi. The Politics of Gay Marriage in Latin America: Argentina, Chile, and Mexico.

- ↑ "National Mental Health Programme". nhp.gov.in. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Sinha, Suman K.; Kaur, Jagdish. "National mental health programme: Manpower development scheme of eleventh five-year plan". PMC 3221186

. PMID 22135448. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.86821.

. PMID 22135448. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.86821.

- ↑ "The European Psychiatric Association". europsy.net. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "About the American Psychiatric Nurses Association: An Introduction". apna.org. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 Neuropsychiatric Disorders (Koho Miyoshi, Yasushi Morimura, Kiyoshi Maeda ed.).

- ↑ "Laureates of the Japan Prize". japanprize.jp. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "Safety of lamotrigine in paediatrics: a systematic review". PMC 4466618

. PMID 26070796. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007711. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

. PMID 26070796. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007711. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ "Ken Kwong recalls the early days of fMRI". martinos.org. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Sertraline". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ Nevels, Robert M.; Gontkovsky, Samuel T.; Williams, Bryman E. "Paroxetine—The Antidepressant from Hell? Probably Not, But Caution Required". PMC 5044489

. PMID 27738376.

. PMID 27738376.

- ↑ Sansone, Randy A.; Sansone, Lori A. "Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: A Pharmacological Comparison". PMC 4008300

. PMID 24800132.

. PMID 24800132.

- ↑ "Leading the charge in leptin research: an interview with Jeffrey Friedman". PMC 3424452

. PMID 22915017. doi:10.1242/dmm.010629.

. PMID 22915017. doi:10.1242/dmm.010629.

- ↑ "Leptin: a pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Citalopram and Escitalopram: A Summary of Key Differences and Similarities". psychopharmacologyinstitute.com. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ "European Brain Council: partnership to promote European and national brain research". cell.com. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "European Brain Council: Partnership to promote European and national brain research.". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ Carlsson, B; Holmgren, A; Ahlner, J; Bengtsson, F. "Enantioselective analysis of citalopram and escitalopram in postmortem blood together with genotyping for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19.".

- ↑ Moore, Rhonda J. Handbook of Pain and Palliative Care: Biobehavioral Approaches for the Life Course.