Timeline of water transport

This is a timeline of water transport, focusing on the evolution of watercraft.

Contents

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Prehistory | The earliest seaworthy boats may have been developed as early as 45,000 years ago, at the time of the first migration of humans into Australia. |

| Ancient history | The Ancient Egyptians already have knowledge of sail construction.[1] Sails are also used in boats in Mesopotamia. The Canal of the Pharaohs and the Lighthouse of Alexandria are early pieces of infrastructure for water navigation. |

| 17th century | The first submarine is built in this century. |

| 18th century | The Industrial Revolution brings steam power to the vessels, with the first steamboats built in the late century. At around the same time, the construction of acueducts and canals accelerate in Western Europe. |

| 19th century | The first steam–powered transatlantic, the first ship to transport a cargo of oil, and the first purpose-built icebreaker are made in this century. Antarctica becomes the last continent to be discovered by means of watercraft. |

| 20th century | The first aircraft carrier is used in warfare in 1918. Nuclear-powered vessels appear in the 1950s. The container revolution in shipping begins in the late 1960s. By 1983, 90% of countries would have container ports, compared to 1% in 1966.[2] |

| 21th century | There are more than 6,000 container vessels currently in service.[3] Cruising has become an important part of the tourism industry. |

Full timeline

| Year | Category | Event | Geographical location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45000 BC | Navigation milestone | The first humans arrive in Australia, presumably by boats and land bridge.[4] | Australia | |

| 6000 BC | Watercraf type | Egyptians already travel in reed boats.[5] | Egypt | |

| 4500 BC | Technology | Mesopotamians make a significant advancement in water transport by adding sails to their boats. This innovation marks one of the earliest uses of wind power for propulsion, allowing boats to travel more efficiently across rivers and seas. By harnessing the wind, Mesopotamian sailors can reduce reliance on rowing, thus enabling longer and faster journeys, particularly along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This development lays the foundation for more advanced sailing technologies, eventually influencing maritime travel and trade across the ancient world, contributing to the growth of Mesopotamia as a cradle of civilization.[5] | Irak | |

| 3500 BC | Watercraft type | Oar-powered ships begin to navigate the Eastern Mediterranean seas, marking a pivotal development in ancient maritime technology. These early vessels, often built from wood and featuring a series of oars, are designed for both cargo transport and warfare. Their construction allows them to be agile and maneuverable in the varied and often challenging sea conditions of the region. The use of oars enables these ships to travel faster and more efficiently, facilitating trade and cultural exchange among early civilizations such as the Minoans, Phoenicians, and Egyptians. This advancement in watercraft significantly impacts the growth of maritime trade and exploration in the ancient Mediterranean world.[5] | Mediterranean Sea | |

| 2000 BC? | Infrastructure | The Canal of the Pharaohs is constructed in Egypt, representing a significant advancement in ancient water infrastructure. This canal links the Nile River to the Red Sea, facilitating the movement of goods and people between the two vital waterways. Its construction showcases the Egyptians' engineering prowess and their ability to alter the landscape to suit their needs. The canal plays a crucial role in trade, allowing for efficient transportation of resources like grain and stone, and contributes to Egypt's economic and strategic influence in the ancient world.[6] | Egypt | |

| 1575 BC – 1520 BC | Watercraft type | Dover Bronze Age Boat is constructed, marking the oldest known example of a plank-built vessel. This prehistoric boat, discovered in Dover, England, is significant for its advanced construction techniques, using overlapping planks to create a watertight hull. Measuring approximately 9 meters in length, it reflects sophisticated maritime skills of the Bronze Age. The boat's design indicates it was likely used for coastal navigation or river travel, providing insights into early seafaring practices and the technological innovations of ancient maritime cultures.[7][8][9] | United Kingdom | |

| 542 BC | Watercraft | First written record of a trireme is documented. The trireme is a naval vessel used predominantly by ancient Mediterranean civilizations, including the Greeks and Phoenicians. Characterized by its three rows of oars on each side, manned by skilled rowers, the trireme is known for its speed, agility, and effectiveness in naval battles. Its design allows it to execute complex maneuvers and swift attacks, playing a crucial role in maritime warfare and trade during this period, significantly influencing naval architecture and military strategies in the ancient world.[10] | Mediterranean Sea | |

| 247 BC | Infrastructure | The Lighthouse of Alexandria, also known as the Pharos of Alexandria, is completed on the small island of Pharos in the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt. This monumental structure would be known as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and serves as a crucial navigational aid for sailors in the Mediterranean Sea. Standing approximately 100 to 130 meters tall, it is equipped with a large open flame at the top, which is visible for miles and helped guide ships safely into the busy harbor. Its design would influence future lighthouses throughout history.[11][12][13] | Egypt | |

| 214 BC | Infrastructure | The Lingqu Canal is constructed in China under the direction of Emperor Qin Shi Huang during the Qin Dynasty. This canal, spanning approximately 36 kilometers, is designed to connect the Xiang River, which flows into the Yangtze River, with the Li River, a tributary of the Pearl River. The Lingqu Canal is one of the world's oldest contour canals, utilizing locks and dams to control water flow. Its construction plays a vital role in facilitating transportation, military movements, and economic integration between northern and southern China, reflecting the advanced engineering capabilities of the period.[14][15][16] | China | |

| c.200 AC | Watercraft type | Junks are developed in China, marking a significant advancement in maritime technology. Junks are wooden sailing vessels characterized by their robust design, featuring a flat bottom, high stern, and watertight bulkheads, which provide enhanced stability and safety at sea. Equipped with distinctive, battened sails that can be easily adjusted to varying wind conditions, junks are highly maneuverable and well-suited for long voyages. These ships would play a crucial role in the expansion of Chinese trade, facilitating extensive maritime commerce throughout the South China Sea, Southeast Asia, and beyond. The junk's design would influence shipbuilding in other regions.[17] | China | |

| 984 AC | Infrastructure | Pound locks are introduced in China, representing a significant innovation in water transport infrastructure. Pound locks consist of a chamber with gates at both ends, allowing vessels to be raised or lowered between stretches of water with different levels. This technology is crucial in facilitating the efficient and safe movement of boats along canals and rivers, particularly in regions with significant changes in elevation. The implementation of pound locks greatly improves the navigability of China's extensive canal system, including the Grand Canal, enhancing trade and communication across the empire. This invention would later influence lock designs in Europe and other parts of the world.[18][19][20] | China | |

| c.1000 AC | Navigation milestone | Norse explorer Leif Erikson is believed to have reached North America around this time, making him one of the first Europeans to set foot on the continent. According to Norse sagas, Ericson, the son of Erik the Red, leads an expedition from Greenland and arrives at a land he called Vinland, likely located in what is now Newfoundland, Canada. Ericson's journey highlights the maritime capabilities of the Norse people and their exploration of the Atlantic beyond their established settlements. | Iceland, North Atlantic |  Knarr model, used by Norse sailors |

| 1088 | Technology | Chinese polymath Shen Kuo first describes a magnetic compass in his Dream Pool Essays, marking one of the earliest known descriptions of this important navigation tool. Shen Kuo describes how a lodestone compass can be used to determine direction, particularly for maritime navigation. His account reflects the practical applications of the magnetic compass in water transport, which greatly improves the ability of sailors to navigate long distances. This innovation becomes a critical advancement in navigation, eventually spreading to other parts of the world and revolutionizing sea travel and trade.[21][22][23] | China | |

| 1159 | The Hanseatic League is founded in the Baltic Sea port of Lübeck as a maritime league, initially as a maritime alliance of northern German towns. The league aims to protect mutual trading interests, particularly in the Baltic and North Seas. Lübeck's strategic location helps it become a vital hub for commerce, and the league eventually expands to include numerous cities across Europe. The Hanseatic League would dominate maritime trade in northern Europe during the late Middle Ages, facilitating the exchange of goods like timber, furs, and grain. It would also wield significant political and economic influence until its decline in the 17th century.[24][25][26] | Germany |  Modern, faithful painting of the Adler von Lübeck – the world's largest ship in its time | |

| c.1190 | English scholar Alexander Neckam provides the first known European description of the magnetic compass in his work De naturis rerum. He details the use of a needle magnetized by a lodestone to aid in navigation, specifically for sailors. This marks the introduction of the compass to Europe, a tool that is already in use in China. Neckam’s account demonstrates the growing interest in practical technologies for navigation during the medieval period, and the compass soon becomes indispensable for maritime travel, allowing sailors to determine direction more accurately, especially when landmarks or celestial bodies are obscured.[27] | England | ||

| 13th century | Technology | Portolan charts are introduced in the Mediterranean, marking a significant advancement in navigation technology. These highly detailed maps, often drawn on parchment, depict coastlines, harbors, and compass directions with remarkable accuracy, serving as essential tools for Mediterranean sailors. Unlike earlier maps, portolan charts are based on empirical observation, often using a network of rhumb lines radiating from central points to indicate sailing directions. Their precision revolutionizes maritime navigation, enabling more reliable and efficient sea travel. These charts would remain crucial for European mariners until the advent of more advanced navigational technologies in later centuries.[28][29][30] | ||

| 1620 | Watercraft type | Dutch engineer Cornelis Drebbel constructs the world's first submarine. Drebbel's vessel is an early prototype, made from wood and covered in leather, designed to operate underwater for limited periods. It is powered by oars and can dive to depths of about 15 feet, demonstrating the feasibility of underwater travel. Although primarily intended as a novelty or experimental craft rather than for practical military use, Drebbel's submarine lays the groundwork for future developments in underwater navigation and naval warfare.[31][32][33] | Netherlands | |

| 1757 | Technology | London astronomer John Bird invents the first sextant, a crucial advancement in navigational technology. The sextant, an instrument used to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon, greatly improves the accuracy of celestial navigation. This device allows sailors to determine their latitude and longitude more precisely, enhancing their ability to navigate the seas. Bird’s sextant is a refinement of earlier instruments, such as the octant, and its design incorporates improvements in precision and usability. The sextant would become an essential tool for maritime navigation, significantly influencing exploration and trade during the Age of Discovery and beyond.[34][35][36] | United Kingdom | |

| 1783 | Watercraft | French engineer Claude de Jouffroy constructs the first recorded steamboat, known as the Pyroscaphe. Powered by a steam engine, the boat is tested on the Saône River in France. De Jouffroy's steamboat is a significant advancement in watercraft technology, as it demonstrates the potential of steam power for propulsion, a concept that would eventually revolutionize transportation. While the Pyroscaphe itself is not commercially successful due to technical limitations and lack of sustained development, it paves the way for future innovations in steam-powered vessels, leading to the eventual rise of steamships in the 19th century.[37][38][39] | France | |

| 1787 | Watercraft type | American inventor John Fitch designs the first steamboat in the United States. Fitch's steamboat, powered by a steam engine driving a series of paddles, successfully navigates the Delaware River during its public demonstration. This marks a pioneering moment in American transportation, showcasing the potential of steam-powered vessels for commercial and passenger use. Although Fitch's early steamboats would be not widely adopted due to technical and financial challenges, his work lays the groundwork for the development of more practical steam-powered watercraft, which would eventually revolutionize river and ocean travel in the 19th century.[40][41][42] | United States | |

| 1790 | Infrastructure | Canal Mania –a period of intense canal building, begins in England and Wales, marking a period of intense canal construction driven by the growing demands of the Industrial Revolution. The development of an extensive canal network enables the efficient transportation of heavy goods such as coal, iron, and raw materials between industrial centers and ports. This infrastructure boom is fueled by both public and private investment, as canals provide a cheaper and more reliable method of transportation compared to overland routes. Canal Mania significantly boosts trade and economic growth, shaping the infrastructure of Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[43][44][45] | United Kingdom | |

| 1797 | Infrastructure | The Lune Aqueduct is completed, marking a significant achievement in water transport infrastructure in England. Spanning the River Lune near Lancaster, this aqueduct is a key feature of the Lancaster Canal, designed to carry waterborne traffic over the river. The aqueduct not only facilitates the movement of goods and people but also demonstrates advancements in engineering that would contribute to the growth of Britain's canal network during the Industrial Revolution.[46] | United Kingdom | |

| 1799 | Infrastructure | The Edstone Aqueduct is completed as part of the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal in Warwickshire, England. This structure, the longest aqueduct in England at 146 meters, is designed to transport canal boats over a railway and a small road. Constructed with an iron trough supported by masonry piers, the aqueduct reflects the engineering advancements of the late 18th century. It would play a significant role in facilitating the movement of goods during the Industrial Revolution, contributing to the growth of Britain's canal network and the efficiency of water-based transport.[46] | United Kingdom | |

| 1803 | Watercraft type | Scottish engineer William Symington's steamboat, the Charlotte Dundas, makes its first voyage, marking a pivotal moment in maritime history. Generally regarded as the world's first practical steamboat, the Charlotte Dundas demonstrates the viability of steam-powered vessels for water transport. Powered by a Watt steam engine and equipped with a paddle wheel, the steamboat successfully tows two barges along the Forth and Clyde Canal in Scotland. This innovation paves the way for the widespread use of steamships in commercial and passenger transport, revolutionizing the shipping industry and global trade.[47][48][49] | United Kingdom | |

| 1804 | Watercraft type | American inventor Oliver Evans builds one of the earliest amphibious vehicles, showcasing his innovative engineering skills. Known as the Orukter Amphibolos, this steam-powered vehicle can travel on both land and water, making it a pioneering creation in transportation technology. Originally designed as a dredging machine, the Orukter Amphibolos is equipped with wheels for land movement and paddles for water navigation. While not widely adopted, Evans' invention marks a significant milestone in the development of multi-terrain vehicles, demonstrating the potential for steam power in versatile transportation applications.[50][51][52] | United States | |

| 1805 | Infrastructure | The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is completed in Wales, becoming an iconic feat of engineering. Designed by Thomas Telford and William Jessop, this aqueduct carries the Llangollen Canal over the River Dee in Denbighshire. Spanning 307 meters with 18 slender stone piers, it is the longest and highest aqueduct in Britain. Its cast iron trough and innovative design makes it a landmark in civil engineering, enabling efficient water transport during the Industrial Revolution. The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct would be inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, symbolizing the ingenuity and ambition of early 19th-century infrastructure projects.[46] | United Kingdom | |

| 1807 | Watercraft type | American engineer Robert Fulton develops the North River Steamboat, also known as the Clermont, which becomes the first commercially successful steamboat. Powered by a steam engine designed by Fulton and built by Watt and Boulton, the *Clermont* demonstrated the viability of steam-powered vessels for regular passenger and freight transport. It made its maiden voyage along the Hudson River from New York City to Albany, covering the distance in about 32 hours. This achievement revolutionized river transport, leading to the widespread adoption of steamboats and transforming trade and travel in the United States.[53][54][55] | United States | |

| 1807 | Technology | French inventor Nicéphore Niépce patents his Pyréolophore, the world's first internal combustion engine. Unlike later gasoline-powered engines, the Pyréolophore uses a mixture of controlled explosions from powdered fuel, such as lycopodium or coal dust, to produce mechanical energy. Initially installed in a boat on the Saône River in France, this pioneering invention marks a crucial step in the development of modern engines. Although not widely adopted at the time, the Pyréolophore lays the groundwork for future advancements in internal combustion technology, revolutionizing transportation and industry.[56][57][58] | France | |

| 1819 | Technology | The SS Savannah makes the first transatlantic crossing by a steamship, from Savannah, Georgia to London.[59][60][61] | United States, United Kingdom | |

| 1820 | Notable voyage | Russian officer Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen discovers mainland Antarctica.[62][63][64] | ||

| 1821 | Infrastructure | The Avon Aqueduct is completed in Scotland.[46] | United Kingdom | |

| 1859 | Watercraft type | The first ironclad warship, the Gloire, is launched.[65][66][67] | France | |

| 1861 | Watercraft type | The Elizabeth Watt is generally credited for being the first ship to transport a cargo of oil across the Atlantic.[68] | ||

| 1861 | Watercraft type | The USS Ice Boat (1861) launches as the first purpose-built icebreaker.[69][70] | United States | |

| 1864 | Technology | Ictineo II, by Spanish engineer Narcís Monturiol, becomes the first submarine powered by an internal-combustion engine.[71][72][73] | Spain | |

| 1869 | Infrastructure | The Suez Canal opens.[74][75][76] | Egypt | |

| 1893 | Infrastructure | The Corinth Canal opens.[77][78][79] | Greece | |

| 1895 | Infrastructure | The Kiel Canal opens.[80][81][82] | Germany | |

| 1896 | Infrastructure | The Briare aqueduct opens.[46] | France | |

| 1897 | Watercraft type | The Turbinia is launched. It is the first vessel to be powered by a steam turbine.[83][84][85] | United Kingdom | |

| 1911 | Watercraft type | Glenn Curtiss builds an early hydroplane.[86][87][88] | United States | |

| 1911 | Technology | The MS Selandia becomes the first important ocean-going vessel to be diesel powered.[89][90][91] | Denmark | |

| 1914 | Infrastructure | The Panama Canal opens.[92][93][94] | Panama | |

| 1915 | Watercraft type | Austrian naval officer Dagobert Müller von Thomamühl creates the first air cushion torpedo speedboat.[95] | Austria | |

| 1918 | Watercraft type | The HMS Furious (47) becomes the first aircraft carrier used in warfare.[96][97][98] | United Kingdom | |

| 1955 | Watercraft type | USS Nautilus (SSN-571) launches as the world's first nuclear-powered vessel.[99][100][101] | United States | |

| 1957 | Watercraft type | Malcom McLean's Gateway City, the first ever ship specifically designed to carry containers, makes its first voyage from New Jersey to Miami.[3] | United States | |

| 1959 | Notable voyage | The USS Skate (SSN-578) surfaces at the North Pole.[102][103][104] | ||

| 1961 | Infrastructure | The Ringvaart Aqueduct is built in the Netherlands.[46] | Netherlands | |

| 1966 | Notable voyage | Sea-Land’s Fairland sails from the United States to the Netherlands with 236 containers on-board, in the first international container ship voyage.[3] | United States, Netherlands | |

| 1966 | Infrastructure | Around 1% of countries have container ports.[3] | ||

| 1977 | Notable voyage | Soviet icebreaker Arktika makes the first surface voyage to the North Pole.[105][106][107] | ||

| 1983 | Infrastructure | 90% of countries have container ports, up from 1% in 1966.[3] | ||

| 1985 | Watercraft type | The Sea Shadow (IX-529), an early stealth ship, is launched.[108] | United States | |

| 1994 | Technology | The Global Positioning System (GPS) becomes operational.[109][110][111] | ||

| 2002 | Infrastructure | The Sart Canal Bridge in Belgium is completed, marking the end of a four-year construction period that began in 1998. Stretching 498 meters, it is built with 65,000 tons of concrete and serves as a crucial link between the Canal du Centre's Grand Large lake and the Brussels–Charleroi Canal. The bridge facilitates navigation and transportation of up to 80,000 tons of water, featuring a unique design with U-shaped girders and prestressed concrete.[112] | Belgium | |

| 2003 | Infrastructure | The Magdeburg Water Bridge opens.[46] | Germany | |

| 2003 | Infrastructure | The Krabbersgat Naviduct opens in the Netherlands.[46] | Netherlands | |

| 2006 | Watercraft type | MS Freedom of the Seas is introduced and becomes the largest cruise liner at the time. It can accommodate 3,634 passengers and 1,300 crew on fifteen passenger decks.[113] | ||

| 2011 | Cruising accounts for US$29.4 billion with over 19 million passengers carried worldwide in the year.[114] | |||

| 2012 | Watercraft type | Canadian filmmaker and deep-sea explorer James Cameron reaches the Challenger Deep solo with the Deepsea Challenger.[115][116][117] | ||

| 2018 | Watercraft type | MS Symphony of the Seas, the world's largest cruise ship by gross tonnage at 228,021 GT, sets sail from Barcelona.[118] | Spain |

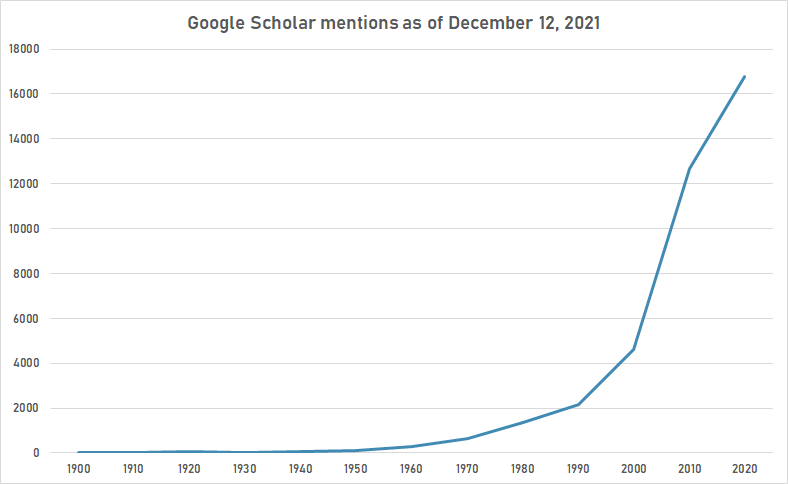

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 12, 2021.

| Year | "water transport" |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 17 |

| 1910 | 16 |

| 1920 | 50 |

| 1930 | 34 |

| 1940 | 48 |

| 1950 | 102 |

| 1960 | 269 |

| 1970 | 662 |

| 1980 | 1,380 |

| 1990 | 2,150 |

| 2000 | 4,620 |

| 2010 | 12,700 |

| 2020 | 16,800 |

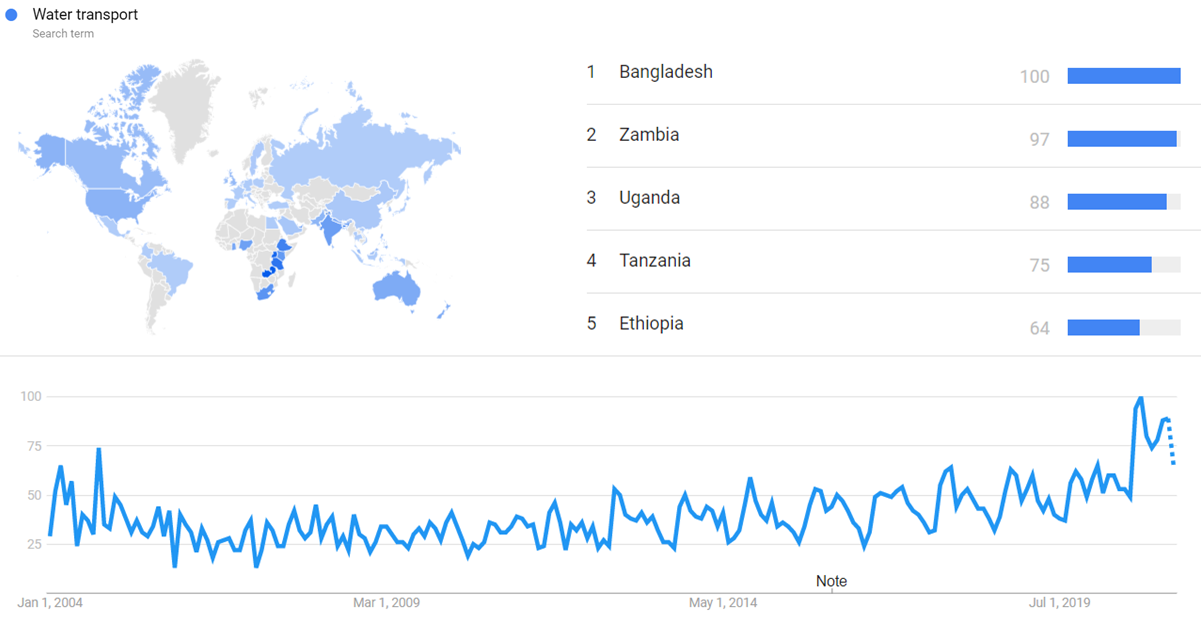

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Water transport (Search term), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[119]

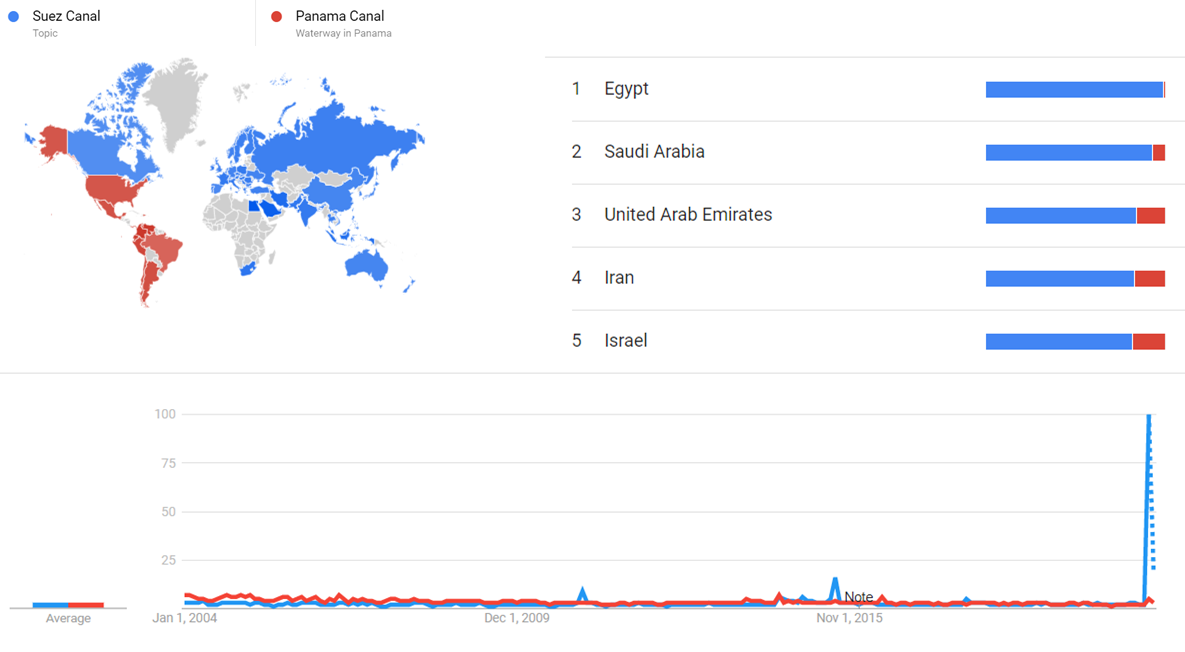

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Suez Canal (Topic) and Panama Canal (Waterway in Panama), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[120]

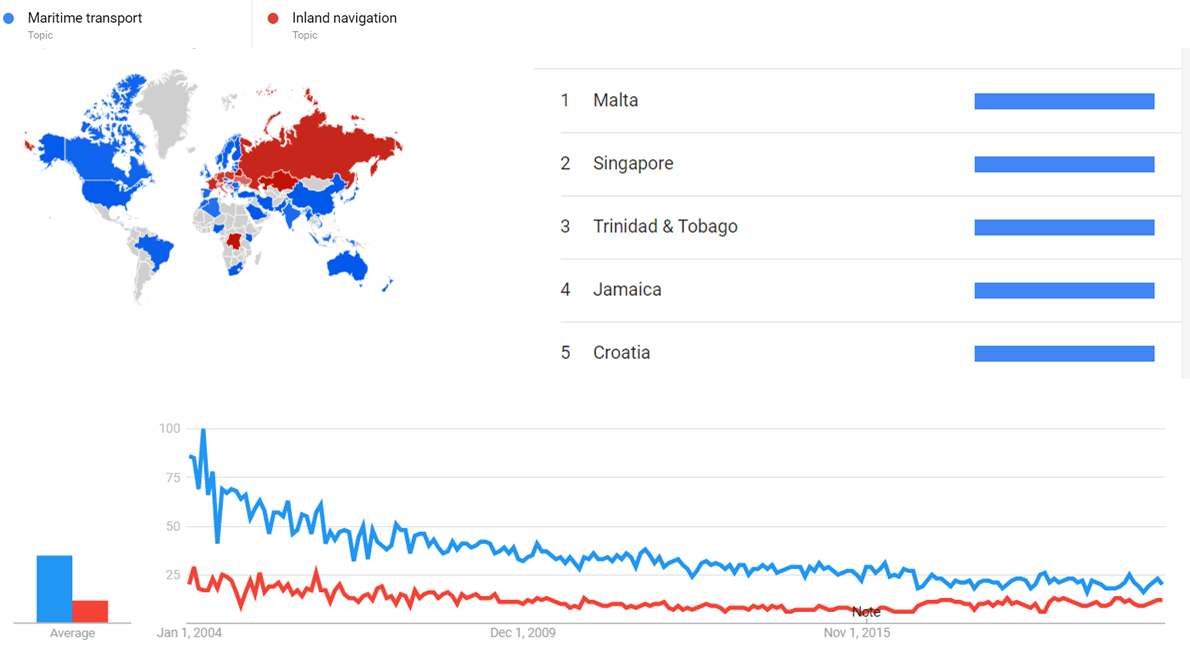

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Maritime transport (Topic) and Inland navigation (Topic), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[121]

Google Ngram Viewer

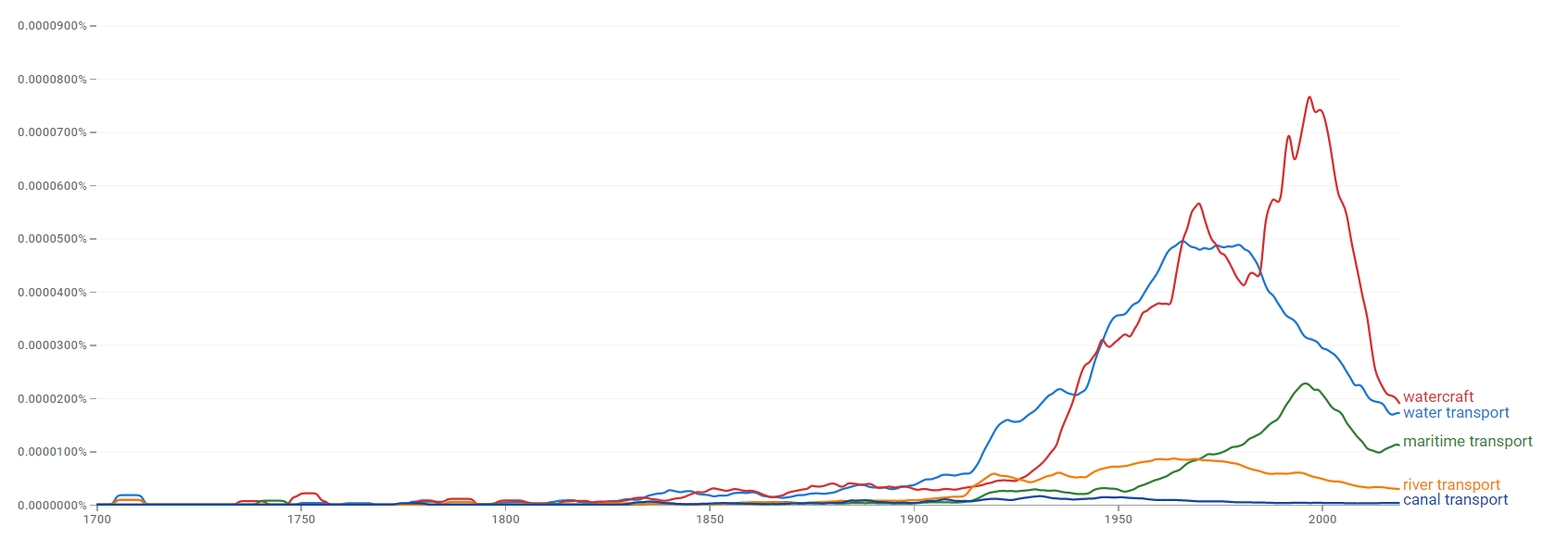

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Water transport, watercraft, maritime transport, river transport and canal transport, from 1700 to 2019.[122]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Hatshepsut oversaw the preparations and funding of an expedition of five ships, each measuring seventy feet long, and with several sails. Various others exist, also.

- ↑ Stratton, Michael; Trinder, Barrie Stuart. Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "A Complete History Of The Shipping Container". containerhomeplans.org. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian; Durrani, Nadia. People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 McFaul, Thomas R.; Brunsting, Al. God Is Here to Stay: Science, Evolution, and Belief in God.

- ↑ Burchell, S. C. The Suez Canal.

- ↑ Arnold, Béat; Clark, Peter. The Dover Bronze Age Boat in Context: Society and Water Transport in Prehistoric Europe.

- ↑ Van de Noort, Robert. North Sea Archaeologies: A Maritime Biography, 10,000 BC - AD 1500.

- ↑ Turney, Chris; Canti, Matthew; Branch, Nick; Clark, Peter. Environmental Archaeology: Theoretical and Practical Approaches.

- ↑ Treister, Michail Yu. The Role of Metals in Ancient Greek History.

- ↑ Kamath, Anjali. Seven Wonders Of Worlds.

- ↑ Splinter, Robert. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Applied and Engineering Physics, Three-Volume Set.

- ↑ Cline, Teresa. On a Tall Budget and Short Attention Span (Full Color).

- ↑ Sweeting, Marjorie M. Karst in China: Its Geomorphology and Environment.

- ↑ Developing Gratitude in Children and Adolescents (Jonathan R. H. Tudge, Lia Beatriz de Lucca Freitas ed.).

- ↑ Xu, Gang. Tourism and Local Development in China: Case Studies of Guilin, Suzhou and Beidaihe.

- ↑ "Chinese junks". historyanswers.co.uk. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ Temple, Robert K. G. China: Land of Discovery [and Invention].

- ↑ Menzies, Gavin. 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance.

- ↑ Landry, Elaine; Dartford, Mark; Morris, Trevor. The New Illustrated Science and Invention Encyclopedia: The New how it Works, Volume 11.

- ↑ Stein, Stephen K. The Sea in World History: Exploration, Travel, and Trade [2 volumes].

- ↑ DK. Science Year by Year: A Visual History, From Stone Tools to Space Travel.

- ↑ Whitehouse, David. Journey to the Centre of the Earth: The Remarkable Voyage of Scientific Discovery into the Heart of Our World.

- ↑ Ciment, James. How They Lived: An Annotated Tour of Daily Life through History in Primary Sources [2 volumes]: An Annotated Tour of Daily Life through History in Primary Sources.

- ↑ A Companion to the Hanseatic League.

- ↑ Henningsen, Bernd; Etzold, Tobias; Hanne, Krister. The Baltic Sea Region: A Comprehensive Guide: History, Politics, Culture and Economy of a European Role Model.

- ↑ Lanza, Roberto; Meloni, Antonio (2006). The earth's magnetism an introduction for geologists

. Berlin: Springer. p. 255. ISBN 978-3-540-27979-2.

. Berlin: Springer. p. 255. ISBN 978-3-540-27979-2.

- ↑ "Portolan Chart of the Mediterranean Sea". bl.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Portolan chart". britannica.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Portolan Charts". beinecke.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ Thornton, W.M. Submarine Insignia and Submarine Services of the World.

- ↑ The Submarine. United States Navy.

- ↑ Broadwater, Robert P. Civil War Special Forces: The Elite and Distinct Fighting Units of the Union and Confederate Armies: The Elite and Distinct Fighting Units of the Union and Confederate Armies.

- ↑ Pickthall, Barry. A History of Sailing in 100 Objects.

- ↑ Campbell, Douglas E.; Chant, Stephen J. Patent Log: Innovative Patents that Advanced the United States Navy.

- ↑ Stein, Stephen K. The Sea in World History: Exploration, Travel, and Trade [2 volumes].

- ↑ Mapp, Alf J. Three Golden Ages: Discovering the Creative Secrets of Renaissance Florence, Elizabethan England, and America's Founding.

- ↑ Owen Philip, Cynthia. Robert Fulton: A Biography.

- ↑ Headrick, Daniel R. Power over Peoples: Technology, Environments, and Western Imperialism, 1400 to the Present.

- ↑ McCloy, Shelby T. French Inventions of the Eighteenth Century.

- ↑ Grayson, Robert. The U.S. Industrial Revolution.

- ↑ Barth, Linda J. New Jersey Originals: Technological Marvels, Odd Inventions, Trailblazing Characters and More.

- ↑ Samuelson, James. The Civilization of Our Day: A Series of Original Essays on Some of Its More Important Phases at the Close of the Nineteenth Century.

- ↑ Scientific American: Supplement, Volume 61. Munn and Company.

- ↑ Burton, Anthony. Richard Trevithick: Giant of Steam.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 46.6 46.7 "10 Of the World's Most Amazing Water Bridges". interestingengineering.com. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ Growing Up with Science. Marshall Cavendish Corporation.

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines.

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian. The Great Railway Revolution: The Epic Story of the American Railroad.

- ↑ Shallat, Todd A. Structures in the Stream: Water, Science, and the Rise of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, Volume 7: 28 November 1813 to 30 September 1814.

- ↑ Clark, Daniel-Kinnear; Colburn, Zerah. Recent Practice in the Locomotive Engine ... Comprising the Latest English Improvements, and a Treatise on the Locomotive Engines of the United States.

- ↑ Schwarz, George R. The Steamboat Phoenix and the Archaeology of Early Steam Navigation in North America.

- ↑ Adams, Arthur G. The Hudson Through the Years.

- ↑ Ward, John D. An Account of the Steamboat Controversy Between the Citizens of New York and New Jersey, from 1811 to 1824: Originating in the Asserted Claim of New York to the Exclusive Jurisdiction Over All the Waters Between the Two States.

- ↑ Hannavy, John. Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography: A-I, index.

- ↑ Winterton, Wayne. Stories from History’S Dust Bin, Volume 1.

- ↑ Hughes, Stefan. Catchers of the Light: The Forgotten Lives of the Men and Women Who First Photographed the Heavens.

- ↑ McDonogh, Gary W. Black and Catholic in Savannah, Georgia.

- ↑ Blume, Kenneth J. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Maritime Industry.

- ↑ Beney, Peter. The Majesty of Savannah.

- ↑ World Exploration From Ancient Times. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ Cantrill, David J.; Poole, Imogen. The Vegetation of Antarctica Through Geological Time.

- ↑ Kramme, Michael. Exploring Antarctica, Grades 5 - 8.

- ↑ Broadwater, John D. USS Monitor: A Historic Ship Completes Its Final Voyage.

- ↑ Stein, Stephen K. The Sea in World History: Exploration, Travel, and Trade [2 volumes].

- ↑ American Pageant Complete. CTI Reviews.

- ↑ "Historical Development of the Pipeline as a Mode of Transportation" (PDF). gammathetaupsilon.org. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ "NavSource Online: "Old Navy" Ship Photo Archive". navsource.org. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Phila. Ice Boat. Navy Yard. Washington DC May 23/61.". americancivilwarphotos.com. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Verne, Jules. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

- ↑ Cairns, Lynne. Secret Fleets: Fremantle's World War II Submarine Base.

- ↑ Chaffin, Tom. The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy.

- ↑ Raugh, Harold E. The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History.

- ↑ Burns, Maria G. Port Management and Operations.

- ↑ Graf, Arndt; Huat, Chua Beng. Port Cities in Asia and Europe.

- ↑ De Wire, Elinor; Reyes-Pergioudakis, Dolores. The Lighthouses of Greece.

- ↑ di Castri, F.; Hansen, A.J.; Debussche, M. Biological Invasions in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin.

- ↑ Tan, T. S. Characterisation and Engineering Properties of Natural Soils, Volume 2.

- ↑ Yang, Haijiang. Jurisdiction of the Coastal State over Foreign Merchant Ships in Internal Waters and the Territorial Sea.

- ↑ Aust, Anthony. Handbook of International Law.

- ↑ Platzöder, Renate; Verlaan, Philomène A. The Baltic Sea: New Developments in National Policies and International Cooperation.

- ↑ Blume, Kenneth J. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Maritime Industry.

- ↑ Newton, David E. Encyclopedia of Water.

- ↑ DK. 1000 Inventions and Discoveries.

- ↑ San Diego: a California City. San Diego Historical Society.

- ↑ Flying Magazine May 1967.

- ↑ Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Schobert, Harold H. Energy and Society: An Introduction.

- ↑ Ville, Simon. Shipbuilding in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century: A Regional Approach.

- ↑ Kaplan, Philip. Naval Air: Celebrating a Century of Naval Flying.

- ↑ Aguirre, Robert. The Panama Canal.

- ↑ the panama canal in transition.

- ↑ LOIZILLON, GABRIEL J. THE BUNAU-VARILLA BROTHERS AND THE PANAMA CANAL.

- ↑ "Müller (von) Thomamühl, Dagobert". austria-forum.org. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Shipbuilding and Shipping Record, Volume 49, Part 2.

- ↑ Friedman, Norman. British carrier aviation: the evolution of the ships and their aircraft.

- ↑ Kaplan, Philip. Naval Air: Celebrating a Century of Naval Flying.

- ↑ Castellano, Robert N. Alternative Energy Technologies: Opportunities and Markets.

- ↑ Страутман, Лидия; Гумарова, Шолпан; Сабырбаева, Назигуль. Introduction to the World of Physics. Методическое пособие по переводу научно-технических текстов.

- ↑ Skaarup, Harold A. New England Warplanes: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut.

- ↑ Silverstone, Paul. The Navy of the Nuclear Age, 1947–2007.

- ↑ US Military.

- ↑ United States Submarine Veterans, Inc: The First 40 Years. United States Submarine Veterans.

- ↑ Valsson, Trausti. How the World Will Change with Global Warming.

- ↑ Nuttall, Mark. Encyclopedia of the Arctic.

- ↑ Armstrong, Terence E.; Okhuizen, Edwin; Bulatov, V. N.; Nielsen, Jens Petter. Historical and Current Uses of the Northern Sea Route: ] pt. 4. the administration of the northern sea route (1917-1991).

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. U.S. Conflicts in the 21st Century: Afghanistan War, Iraq War, and the War on Terror [3 volumes]: Afghanistan War, Iraq War, and the War on Terror.

- ↑ Fossen, Thor I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control.

- ↑ Neunzert, Gaby M. Subdividing the Land: Metes and Bounds and Rectangular Survey Systems.

- ↑ Auerbach, Paul S. Wilderness Medicine E-Book: Expert Consult Premium Edition - Enhanced Online Features.

- ↑ "The Sart Canal Bridge: Belgium's Concrete Marvel". Hasan Jasim. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ↑ "Top 10 Most Expensive Cruise Ships Ever Built". worldmaritimenews.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Cruise Market Watch Announces 2011 Cruise Line Market Share and Revenue Projections". Cruise Market Watch. accessdate=11 July 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "James Cameron Headed to Ocean's Deepest Point Within Weeks". news.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "James Cameron Makes First Ever Successful Solo Dive to Mariana Trench". press.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "James Cameron plunges solo to deepest spot in world's oceans". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ "Symphony of the Seas: World's largest cruise ship sets sail". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Water transport". Google Trends. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Suez Canal and Panama Canal". Google Trends. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Maritime transport and Inland navigation". Google Trends. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Water transport, watercraft, maritime transport, river transport and canal transport". books.google.com. Retrieved 28 April 2021.