Timeline of influenza

This is a timeline of influenza, briefly describing major events such as outbreaks, epidemics, pandemics, discoveries and developments of vaccines. In addition to specific year/period-related events, there's the seasonal flu that kills between 250,000 and 500,000 people every year, and has claimed between 340 million and 1 billion human lives throughout history.[1][2]

Contents

Big Picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Prior to the 18th century | The outbreak of influenza reported in 1173 is not considered to be a pandemic, and other reports to 1500 generally lack reliability. The outbreak of 1510 is probably a pandemic reported with spreading from Africa to engulf Europe. The outbreak of 1557 is possibly a pandemic. The first influenza pandemic agreed by all authors occurs in 1580.[3] |

| 18th century | Data from this century is more informative of pandemics that those of previous years. The first agreed influenza pandemic of the 18th century begins in 1729.[3] |

| 19th century | Two influenza pandemics are recorded in the century.[3] Avian influenza is recorded for the first time.[4] |

| 20th Century | Influenza pandemics are recorded four times, starting with the deadly Spanish flu. This is also the period of virus isolation and development of vaccines.[5] Prior to 20th century, much information about influenza is generally not considered certain. Although the virus seems to have caused epidemics throughout human history, historical data on influenza are difficult to interpret, because the symptoms can be similar to those of other respiratory diseases.[6][7] |

| 1945-21th century | International health organizations merge, and large scale vaccination campaigns begin.[8] |

| 21th century | Worldwide accessible databases multiply in order to control outbreaks and prevent pandemics. New influenza strain outbreaks still occur. Efficacy of currently available vaccines is still insufficient to diminish the current annual health burden induced by the virus.[8] |

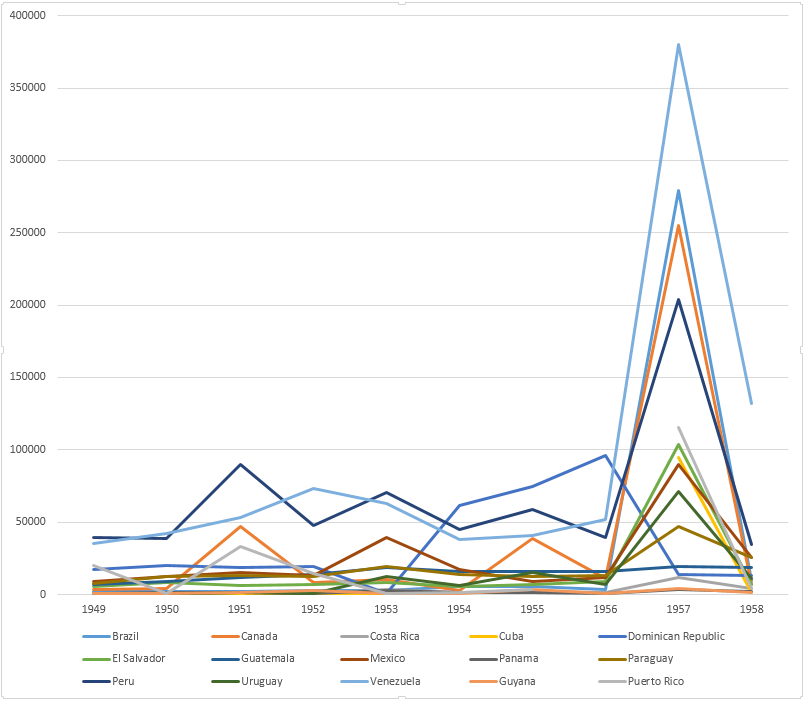

Visual data

Full timeline

| Year/period | Strain | Species | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 BCE | Medical development | The symptoms of human influenza are described by Hippocrates.[10][5] | |||

| 1173 | Epidemic | First epidemic, where symptoms are probably influenza, is reported.[3] | |||

| 1357 | Human | Medical development | The term influenza is first used to describe a disease prevailing in 1357. It would be applied again to the epidemic in 1386−1387.[11] | Italy | |

| 1386–1387 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza-like illness epidemic develops in Europe, preferentially killing elderly and debilitating persons. This is probably the first documentation of a key epidemiological feature of both pandemic and seasonal influenza.[11] | Europe | |

| 1411 | Human | Epidemic | Epidemic of coughing disease associated with spontaneous abortions is noted in Paris.[11] | France | |

| 1510 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic invades Europe from Africa in the summer of 1510 and proceedes northward to involve all of Europe and then the Baltic States. Attack rates are extremely high, but fatality is low and said to be restricted to young children.[11] | Africa, Europe | |

| 1557–1558 | Human | Epidemic | The first influenza pandemic in which global involvement and westward spread from Asia to Europe is documented. Unlike the previous pandemic from 1510, this one is highly fatal, with deaths recorded as being due to "pleurisy and fatal peripneumony". High mortality in pregnant women is also recorded.[11] | Eurasia | |

| 1580 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic originates in Asia during the summer, spreading to Africa, and then to Europe along two corridors from Asia Minor and North-West Africa. Illness rates are high. 8000 deaths are reported in Rome, and some Spanish cities are decimated.[3][11] | Eurasia, Africa | |

| 1729 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic originates in Russia, spreading westwards in expanding waves to embrace all Europe within six months. High death rates are reported.[7][3][11] | Eurasia | |

| 1761–1762 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic originates. Remarkably it is estimated to have begun in the Americas in the spring of 1761 and to have spread from there to Europe and around the globe in 1762. It is the first pandemic to be studied by multiple observers who communicate with each other in learned societies and through medical journals and books. Influenza is characterized clinically to a greater degree than it has been previously, as physicians carefully record observations on series of patients and attempt to understand what would later be called the pathophysiology of the disease.[11] | Americas, Europe | |

| 1780–1782 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic originates in Southeast Asia and spreads to Russia and eastward into Europe. It is remarkable for extremely high attack rates but negligible mortality. It appears that in this pandemic the concept of influenza as a distinct entity with characteristic epidemiological features is first appreciated.[11] | Eurasia | |

| 1830–1833 | Human | Epidemic | Influenza pandemic breaks out in the winter of 1830 in China, further spreading southwards by sea to reach the Philippines, India and Indonesia, and across Russia into Europe. By 1831, the epidemic reaches the Americas. Overall the attack rate is estimated at 20–25% of the population, but the mortality rate is not exceptionally high.[3] | Eurasia, Americas | |

| 1878 | Non-human (Avian) | Scientific development | Avian influenza is recorded for the first time. Originally known as Fowl Plague.[4] | Italy | |

| 1889–1892 | Human | Epidemic | 1889–90 flu pandemic. Dubbed the "Russian pandemic". Attack rates are reported in 408 geographic entities from 14 European countries and in the United States. Rapidly spreading, the pandemic would take only 4 months to circumnavigate the planet, reaching the United States 70 days after the original outbreak in Saint Petersburg.[12] Following this pandemic, interest is renewed in examining the recurrence patterns of influenza.[11] | Eurasia, Americas | |

| 1901 | Non-human (Avian) | Scientific development | The causative organism of avian influenza is discovered to be a virus.[13] | ||

| 1918-1920 | H1N1 | Human | Epidemic | The Spanish flu (H1N1) pandemic is considered one of the deadliest natural disasters ever, infecting an estimated 500 million people across the globe and claiming between 50 and 100 million lives. This pandemic would be described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and is estimated to have killed in a single year more people than the Black Death bubonic plague killed in four years from 1347 to 1351.[14][15] | Worldwide; originated in France (disputed) |

| 1931 | Non-human (porcine) | Scientific development | American virologist Richard Shope discovers the etiological cause of influenza in pigs.[16] | ||

| 1933 | Human | Scientific development | British researchers Wilson Smith, Christopher Andrews, and Patrick Laidlaw are the first to identify the human flu virus by experimenting with ferrets.[17][18][19] | United Kingdom | |

| 1936 | Medical development | Soviet scientist A. Smorodintseff first attempts vaccination with a live influenza vaccine that has been passed about 30-times in eggs. Smorodintseff would later report that the modified virus causes only a barely perceptible, slight fever and that subjects are protected against reinfection.[20] | Russia | ||

| 1942 | Medical development | Bivalent vaccine is produced after the discovery of influenza B.[19] | |||

| 1945 | Medical development | The first license to produce an influenza vaccine for civilian use is granted in the United States.[21] | United States | ||

| 1946 | Organization | The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in order to protect public health and safety through the control and prevention of diseases. The CDC would launch campaigns targeting the transmission of influenza.[22][23] | United States (Atlanta) | ||

| 1947 | Organization | The World Medical Association (WMA) is formed as an international confederation of free professional medical associations. Like CDC, the WMA would launch Influenza Immunization Campaigns.[24] | France (serves worldwide) | ||

| 1948 | Organization | The World Health Organization (WHO) is established.[25] | |||

| 1952 | Organization (Research institute) | The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) is established by the WHO with the purpose of conducting global influenza virological surveillance. GISRS monitors the evolution of influenza viruses and provides recommendations in areas including laboratory diagnostics, vaccines, antiviral susceptibility and risk assessment. It also serves as a global alert mechanism for the emergence of influenza viruses with pandemic potential.[26] | |||

| 1956 | Non-human (equine) | Scientific development | Viruses that cause equine influenza are first isolated.[27] | ||

| 1957 | Epidemic | New, virulent influenza A virus subtype H2N2 breaks out in Guizhou (China). It would turn into pandemic (category 2) and kill 1 to 4 million people.[28] It is considered the second major influenza pandemic to occur in the 20th century, after the Spanish flu.[29][11] | China | ||

| 1959 | Non–human infection | Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 breaks out in Scotland and affects domestic chicken.[30] | United Kingdom | ||

| 1961 | Non–human infection | Avian Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 strain is found in birds.[31][32] | South Africa | ||

| 1963 | Non–human infection | Influenza A virus subtype H7N3 breaks out in England and affects domestic turkeys.[30] | United Kingdom | ||

| 1966 | Non–human infection | Influenza A virus subtype H5N9 breaks out in Ontario and affects domestic turkeys.[30] | Canada | ||

| 1968 | Human | Study of 1,900 male cadets after the 1968 Hong Kong A2 influenza epidemic at a South Carolina military academy, compares thee groups: nonsmokers, heavy smokers, and light smokers. Compared with nonsmokers, heavy smokers (more than 20 cigarettes per day) had 21% more illnesses and 20% more bed rest, light smokers (20 cigarettes or fewer per day) had 10% more illnesses and 7% more bed rest.[33]" | United States | ||

| 1968-1969 | Epidemic | Hong Kong flu (H3N2) pandemic breaks out, caused by a virus that has been “updated” from the previously circulating virus by reassortment of avian genes.[11][34] | Eurasia, North America | ||

| 1973 | Program launch | The World Health Organization starts issuing annual recommendations for the composition of the influenza vaccine based on results from surveillance systems that would identify currently circulating strains.[19] | |||

| 1976 | Epidemic | Swine flu outbreak is identified at U.S. army base in Fort Dix, New Jersey. Four soldiers infected resulting in one death. To prevent a major pandemic, the United States launches a vaccination campaign.[35][36] | United States (New Jersey) | ||

| 1976 | H7N7 | Non–human infection | Influenza A virus subtype H7N7 breaks out in Victoria (Australia) and affects domestic chicken.[30] | Australia | |

| 1977 | Epidemic | Russian flu (H1N1) epidemic. New influenza strain in humans. Isolated in northern China. A similar strain prevalent in 1947–57 causes most adults to have substantial immunity. This outbreak is not considered a pandemic because most patients are children.[36] | Russia, China, worldwide | ||

| 1978 | Medical development | The first trivalent influenza vaccine is introduced. It includes two influenza A strains and one influenza B strain.[19] | |||

| 1979 | Human | Study | Surveillance of an influenza outbreak at a military base for women in Israel reveals that influenza symptoms developed in 60.0% of the current smokers vs. 41.6% of the nonsmokers.[37] | Israel | |

| 1980 | Medical development | United States FDA approves influenza vaccine Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), developed for A subtype viruses and type B virus contained in the vaccine.[38] | United States | ||

| 1982 | Human | Study | Study concludes that smoking may substantially contribute to the growth of influenza epidemics affecting the entire population.[39] | ||

| 1983 | Non–human (avian) | Epizootic | Avian Influenza A virus subtype H5N8 breaks out. 8,000 turkeys, 28,020 chickens, and 270,000 ducks are slaughtered.[40][32] | Ireland | |

| 1986 | Literature | Medical geographer Gerald F. Pyle publishes The Diffusion of Influenza.[41] | |||

| 1988 | Infection | Influenza A virus subtype H1N2 is isolated from humans in six cities in China, but the virus does not spread further.[42] | China | ||

| 1990-1996 | Medical development | Oseltamivir (often referenced by its trademark name Tamiflu) is developed by Gilead Sciences, using shikimic acid for synthesis. It would be widely used in further antiviral campaigns targeting influenza A and B. Included on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[43] | United States | ||

| 1993 | Human | Study | In a prospective study of community-dwelling people 60–90 years of age, it is found that 23% of smokers have clinical influenza as compared with 6% of non-smokers.[44] | ||

| 1997 | H5N1 | Human | Infection | Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 (also known as bird flu) is discovered in humans. The first time an influenza virus is found to be transmitted directly from birds to people. Eighteen people hospitalized, six of whom die. Hong Kong kills its entire poultry population of about 1.5 million birds. No pandemic develops.[45] | China (Hong Kong) |

| 1997 | H7N4 | Avian | Epizootic | Highly pathogenic Influenza A virus subtype H7N4 strain causes a minor flu outbreak in chicken in Australia.[46] | Australia |

| 1997 | Human | System launch | FluNet is launched as a global web-based tool for influenza virological surveillance.[47] | ||

| 1998–1999 (November 1998–April 1999) | H3N2, H1N1 | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 1998-1999 season containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere | |

| 1999 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 1999 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 1999 | H9N2 | Infection | New Influenza A virus subtype H9N2 strain is detected in humans. It causes illness in two children in Hong Kong, with poultry being the probable source. No pandemic develops.[36][32] | China (Hong Kong) | |

| 1999–2000 (November 1999 to April 2000) | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 1999-2000 season contain the following:

|

|

| 2000 | Human | Alternative medicine | Homeopathic preparation Oscillococcinum becomes one of the top ten selling drugs in France, is publicised widely in the media, and becomes widely prescribed for both influenza and the common cold.[51] | France | |

| 2000 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2000 season (southern hemisphere winter) contain the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2000–2001 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2000-2001 season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2001 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2001 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2001–2002 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2001-2002 season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

|

| 2002 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2002 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2002 | H7N2 | Non-human (avian) | Infection | New avian influenza A virus subtype H7N2 strain affects 197 farms in Virginia and results in the killing of over 4.7 million birds. One person is infected, fully recovered.[57][32] | United States |

| 2002–2003 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2002-2003 season (Northern Hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2003 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2003 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2003 | Human | System launch | Influenzanet launches in the Netherlands and Belgium as a participatory surveillance system monitoring the incidence of influenza-like illness in Europe. It is based on data provided by volunteers who self-report their symptoms via the Internet throughout the influenza season.[60][61] | Netherlands, Belgium | |

| 2003 | H7N7 | Human, avian | Infection | First reported case of avian influenza A virus subtype H7N7 strain in humans. 88 people are infected, one dies. 30 million birds are slaughtered.[62][32] | Netherlands |

| 2003–2004 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2003-2004 season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

|

| 2003–2007 | H5N1 | Infection | Avian (Influenza A virus subtype H5N1) strain is reported in humans. In February 2003, two people are infected in Hong Kong, one dies. In December 2003, H5N1 breaks out among chicken in South Korea. By January 2004, Japan has its first outbreak of avian flu since 1925 and Vietnam reports human cases. In Thailand, nine million chickens are slaughtered to stop the spread of the disease.[32] By December 2006, over 240 million poultry would die or be culled due to H5N1.[64] See also: Global spread of H5N1 |

East Asia, Southeast Asia | |

| 2004 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2004 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

|

| 2004 | Organization | The Influenza Genome Sequencing Project is launched to investigate influenza evolution by providing a public data set of complete influenza genome sequences from collections of isolates representing diverse species distributions. Funded by the NIAID.[66] | |||

| 2004 | Human | Infection | New avian Influenza A virus subtype H7N3 strain is detected in humans. Two poultry workers become infected, eventually fully recovered.[67][32] | Canada | |

| 2004 | H10N7 | Infection | New avian influenza A virus subtype H10N7 strain is detected in humans. Two children become infected.[68][32] | Egypt | |

| 2004 | H5N2 | Non–human infection | Avian influenza A virus subtype H5N2 infects birds in Texas. 6,600 infected broiler chickens are slaughtered.[69][32] | United States | |

| 2004 | H3N8 | Non-human (Canidae) | Canine influenza (dog flu) virus subtype H3N8, is discovered to cause disease in canines in 2004.[70] | United States | |

| 2004–2005 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2004-2005 northern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2005 | Human | Organization | United States President George W. Bush unveils the National Strategy to Safeguard Against the Danger of Pandemic Influenza. US$1 billion for the production and stockpile of oseltamivir are requested after Congress approves $1.8 billion for military use of the drug.[72][73] | United States | |

| 2005 | General | Organization | American president George W. Bush announces the International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza. The purpose of the partnership is protecting human and animal health as well as mitigating the global socioeconomic and security consequences of an influenza pandemic.[74][75] | United States (New York City) | |

| 2005 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2005 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

|

| 2005 | General | New technology development led by Elodie Ghedin at The Institute for Genomic Research is first published at journal Nature describing over 100 influenza genomes.[77] | |||

| 2005 | H1N1 | Infection | Avian influenza A virus subtype H1N1 strain kills one person in Cambodia. In Romania, a village is quarantined after three dead ducks test positive for H1N1.[78][32] | Cambodia, Romania | |

| 2005–2006 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2005-2006 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

A trivalent vaccine containing:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2006 | Human, avian | Organization | The International Pledging Conference on Avian and Human Pandemic Influenza is held Beijing. Co-hosted by the Chinese Government, the European Commission and the World Bank. The purpose is to raise funds for international cooperation in the prevention and control of avian and human influenza.[80] | China (Beijing) | |

| 2006 | Human | Website launch | FluTrackers (flutrackers.com launches as a website, online forum and early warning system which tracks and gathers information relating to a wide range of infectious diseases, including flu and assists in how to use it to inform the general public.[81] |

||

| 2006 | Human | Website launch | flutracking.net launches in Australia as a weekly web-based survey of influenza-like illness (ILI). It monitors the transmission and severity of ILI across Australia. The survey documents symptoms (cough, fever, and sore throat), time off work or normal duties, influenza vaccination status, laboratory testing for influenza, and health seeking behavior.[82] |

Australia | |

| 2006 | Pandemrix | ||||

| 2006 | Human | Program launch | The Global Action Plan for Influenza Vaccines (GAP) launches as a strategy to reduce the global shortage of influenza vaccines for seasonal epidemics and pandemic influenza in all countries of the world through three major approaches:

The program would close in 2016.[83] |

||

| 2006–2007 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2006-7 season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2007 | Non-human (equine) | Equine influenza outbreak is diagnosed in Australia's horse population following the failure to contain infection in quarantine after the importation of one or more infected horses. The outbreak would also have a major impact on individual horse owners, the horse industry and associated sectors in both infected and uninfected states.[85] | Australia | ||

| 2007 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2007 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2007–2008 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2007-8 season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2008 | Literature | Roni K. Devlin publishes Influenza (Biographies of Disease).[88] | |||

| 2008 | Human | Literature | Antivirals for Pandemic Influenza: Guidance on Developing a Distribution and Dispensing Program is published by the U.S. Institute of Medicine.[89] | United States | |

| 2008 | H5N1 and others | Human, avian | Literature | Avian Influenza, by Hans-Dieter Klenk, Mikhail N. Matrosovich, and Jürgen Stech, is published. It provides information about the ecology and epidemiology of avian influenza with particular emphasis on recent H5N1 outbreaks in China, Siberia and Europe.[90] | |

| 2008 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2008 season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

|

| 2008 | General | Scientific development | Research by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) finds that the influenza virus has a butter-like coating, which melts when it enters the respiratory tract. In the winter, the coating becomes a hardened shell; therefore, it can survive in the cold weather similar to a spore. In the summer, the coating melts before the virus reaches the respiratory tract.[92] | ||

| 2008 | General | Scientific development | OpenFluDB is launched as a database for human and animal influenza virus. It's used to collect, manage, store and distribute worldwide data on influenza.[93] | Worldwide | |

| 2008 | Human | Service launch | Google launches Google Flu Trends, a web service with aims at providing estimates of influenza activity by aggregating Google Search queries. The system would provide data to 29 countries worldwide, extending service to include surveillance for dengue.[94] | United States | |

| 2008–2009 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2008-2009 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2009 | H1N1 | Human | Epidemic | New flu virus (H1N1) pandemic (colloquially called the swine flu pandemic), first recognized in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, spreads quickly across the United States and the world, prompting a strong global public reaction. Overseas flights are discouraged from government health bodies.[96] Worldwide, nearly 1 billion doses of H1N1 vaccine are ordered.[97] A total of 74 countries are affected. 18,500 deaths.[36] | Worldwide |

| 2009 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2009 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2009–2010 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2009-2010 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2010 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2010 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2010 | Human | Literature | Influenza and Public Health: Learning from Past Pandemics is published by Tamara Giles-Vernick, Susan Craddock, and Jennifer Lee Gunn. The book explores past influenza pandemics with the purpose to obtain critical insights into possible transmission patterns, experiences, mistakes, and interventions.[101] | ||

| 2010–2011 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2010-2011 influenza season (northern hemisphere):

| |

| 2011 (March) | General | The World Health Organization releases its global standards and tools for influenza surveillance. The report summarizes the discussions and recommendations concluded in a global consultation aimed at reviewing influenza surveillance standards and the current data-sharing and reporting tools.[103] | |||

| 2011 | H3N8 | Non–human | Epizootic | Influenza A virus subtype H3N8 causes death of more than 160 baby seals in New England.[104] | United States |

| 2011 | General | Scientific development | "Standardization of terminology of the pandemic

A(H1N1)2009 virus" "In order to minimize confusion, and to differentiate the virus from the old seasonal A(H1N1) viruses circulating in humans before the pandemic (H1N1) 2009, the Advisers to the WHO Consultation on the Composition of Influenza Vaccines for the Southern Hemisphere 2012, after discussion on 26 September 2011, advise WHO to use the nomenclature: A(H1N1)pdm09 This standardization will help to minimize potential confusion among the scientific community as well as the general public."[105] |

||

| 2011 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2011 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2011–2012 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2011-2012 influenza season (northern hemisphere) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2012 | Scientific development | A 2012 meta-analysis finds that flu shots are efficacious 67 percent of the time.[108] | |||

| 2012 | Scientific project/controversy | American virologists Ron Fouchier and Yoshihiro Kawaoka intentionally develop a strain based on H5N1 for which no vaccine exists, causing outrage in both the media and scientific community.[109][110][111] | Netherlands (Erasmus Medical Center), United States (University of Wisconsin-Madison) | ||

| 2012 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2012 influenza season (southern hemisphere) containing the following:

|

|

| 2012 | Literature | Yoshihiro Kawaoka and Gabriele Neumann publish Influenza Virus: Methods and Protocols. It summarizes techniques ranging from protocols for virus isolation, growth, and subtyping to procedures for the efficient generation of any influenza virus.[113] | |||

| 2012 | Medical development | United States FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine manufactured using cell culture technology.[114] | United States | ||

| 2012 | Human | Literature | Jonathan Van-Tam publishes Pandemic Influenza, which covers the science and operational application of influenza epidemiology, virology and immunology.[115] | ||

| 2012–2013 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2012-2013 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2013 | H7N9 | Epidemic | Avian Influenza A virus subtype H7N9 strain, a low pathogenic AI virus, breaks out in China. As of April 11, 2014, the outbreak's overall reaches 419 people, including 7 in Hong Kong, with the unofficial death toll at 127.[117][118] | China, Vietnam | |

| 2013 | H1N1 | Literature | Radiology of Influenza A (H1N1) is published by Hongjun Li, presenting the theory of influenza and its imaging characteristics.[119] | ||

| 2013 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2013 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

| |

| 2013 | Medical development | United States FDA approves influenza vaccine Flublok (Protein Sciences), developed through recombinant DNA technology.[121] | United States | ||

| 2013 | H10N8 | Infection | Avian Influenza A virus subtype H10N8 strain infects for the first time and kills one person.[122][32] | China | |

| 2013–2014 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2013-14 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2014 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2014 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2014 | The wholesale price per dose of influenza vaccine in the developing world is about US$5.25 as of year.[125] | Developing world | |||

| 2014–2015 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2014-2015 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2015 | Program | Google Flu Trends shuts down in August 2015 after successive inaccuracies in the big data analysis.[127] After performing well for two to three years since the service launch in 2008, GFT would start to fail significantly and require substantial revision.[128] However, Google Flu Trends would also inspire several other similar projects that use social media data to predict disease trends.[129] | United States | ||

| 2015 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2015 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2015–2016 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2015-2016 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2016 (May) | The Tool for Influenza Pandemic Risk Assessment (TIPRA) is developed by the World Health Organization to provide a standardized and transparent approach to support the risk assessment of influenza viruses with pandemic potential. TIPRA supports hazard assessment by asking a risk question about the pandemic likelihood and impact of an influenza virus.[132] | ||||

| 2016 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2016 influenza season (southern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2016–2017 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2016-2017 influenza season (northern hemisphere winter) containing the following:

an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus; an A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus; a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus.[134] |

Northern hemisphere |

| 2017 | Medical development | Researchers from the University of Texas at Arlington build influenza detector that can diagnose at a breath, without the intervention of a doctor.[135] | United States | ||

| 2017 | H5N6 | Avian | Epizootic | 2017 Central Luzon H5N6 outbreak[136] | Philippines |

| 2017 | Scientific development | Researchers from the University of Helsinki demonstrate that three anti-influenza compounds effectively inhibit zika virus infection in human cells.[137] | Finland | ||

| 2017 | Human | Literature | Influenza and Respiratory Care.[138] | ||

| 2017–2018 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2017-2018 northern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2018 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2018 southern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2019 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2019 southern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

The World Health Organization also recommends that egg based trivalent vaccines for use in the 2019 southern hemisphere influenza season contain the following:

It is recommended that the A(H3N2) component of non-egg based vaccines for use in the 2019 southern hemisphere influenza season be:

|

|

| 2019–2020 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2019-2020 northern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

|

Northern hemisphere |

| 2020 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2020 southern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

WHO also recommends that trivalent influenza vaccines for use in the 2020 southern hemisphere influenza season contain the following:

|

Southern hemisphere |

| 2020–2021 | H3N2, H1N1 | Human | "WHO influenza vaccine formulation recommendation | The World Health Organization recommends vaccines to be used in the 2020 - 2021 northern hemisphere influenza season containing the following:

Egg-based Vaccines:

Cell- or recombinant-based Vaccines:

It is recommended that trivalent influenza vaccines for use in the 2020 - 2021 northern hemisphere influenza season contain the following: Egg-based Vaccines

Cell- or recombinant-based Vaccines

|

Northern hemisphere |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

- [1]

- recommendations

- Influenza vaccine

- Historical annual reformulations of the influenza vaccine

- Influenza treatment

- [2]

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "WHO Europe – Influenza". World Health Organization (WHO). June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ↑ "Influenza: Fact sheet". World Health Organization (WHO). March 2003. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Potter, C. W. "A history of influenza". doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "History of Avian Influenza". extension.org. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lam, Vincent; Lee, Colin. The Flu Pandemic and You: A Canadian Guide. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Beveridge, W I (1991). "The chronicle of influenza epidemics". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 13 (2): 223–234. PMID 1724803.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Potter CW (October 2001). "A History of Influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. PMID 11576290. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Vaccine Analysis: Strategies, Principles, and Control. Springer. 2014. p. 61. ISBN 9783662450246.

- ↑ "REPORTED CASES OF NOTIFIABLE DISEASES IN THE AMERICAS 1949 - 1958" (PDF). paho.org. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Martin, P; Martin-Granel E (June 2006). "2,500-year evolution of the term epidemic". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (6): 976–80. PMC 3373038

. PMID 16707055. doi:10.3201/eid1206.051263.

. PMID 16707055. doi:10.3201/eid1206.051263.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. "Pandemic influenza – including a risk assessment of H5N1". PMC 2720801

.

.

- ↑ "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". pnas.org. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "FLU-LAB-NET - About Avian Influenza". science.vla.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "The Influenza Pandemic of 1918". stanford.edu. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Potter CW (October 2001). "A History of Influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. PMID 11576290. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x.

- ↑ Shimizu, K (October 1997). "History of influenza epidemics and discovery of influenza virus". Nippon Rinsho. 55 (10): 2505–201. PMID 9360364.

- ↑ Smith, W; Andrewes CH; Laidlaw PP (1933). "A virus obtained from influenza patients". Lancet. 2 (5732): 66–68. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)78541-2.

- ↑ Dobson, Mary. 2007. Disease: The Extraordinary Stories behind History’s Deadliest Killers. London, UK: Quercus.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "The Evolving History of Influenza Viruses and Influenza Vaccines 1". medscape.com. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ "The Evolving History of Influenza Viruses and Influenza Vaccines 2". medscape.com. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ P. CROVARI; M. ALBERTI; C. ALICINO. "History and evolution of influenza vaccines". Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa, Italy.

- ↑ Turnock, Bernard J. Public Health. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Ogunseitan, Oladele. Green Health: An A-to-Z Guide. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Influenza Immunization Campaign". wma.net. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Global Health Timeline". Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Global influenza virological surveillance". WHO. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Singh, Raj K.; Khurana, Sandip K.; Chakraborty, Sandip; Malik, Yashpal S.; Virmani, Nitin; Singh, Rajendra; Tripathi, Bhupendra N.; Munir, Muhammad; van der Kolk, Johannes H.; Dhama, Kuldeep; Munjal, Ashok; Khandia, Rekha; Karthik, Kumaragurubaran. "A Comprehensive Review on Equine Influenza Virus: Etiology, Epidemiology, Pathobiology, Advances in Developing Diagnostics, Vaccines, and Control Strategies". doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01941.

- ↑ "Influenza Pandemics". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Asian flu of 1957". britannica.com. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "Avian influenza A(H5N1)- update 31: Situation (poultry) in Asia: need for a long-term response, comparison with previous outbreaks". WHO. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)". Nebraska Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ 32.00 32.01 32.02 32.03 32.04 32.05 32.06 32.07 32.08 32.09 32.10 "Avian flu: a history". Winkler Times. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Finklea JF, Sandifer SH, Smith DD (November 1969). "Cigarette smoking and epidemic influenza". American Journal of Epidemiology. 90 (5): 390–9. PMID 5356947. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121084.

- ↑ Viboud, Cécile; Grais Bernard, Rebecca F.; Lafont, A. P.; Miller, Mark A.; Simonsen, Lone. "Multinational Impact of the 1968 Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic: Evidence for a Smoldering Pandemic". doi:10.1086/431150. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Timeline of Human Flu Pandemics". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 "Pandemic Flu History". accessdate=28 January 2017.

- ↑ Kark JD, Lebiush M (May 1981). "Smoking and epidemic influenza-like illness in female military recruits: a brief survey". American Journal of Public Health. 71 (5): 530–2. PMC 1619723

. PMID 7212144. doi:10.2105/AJPH.71.5.530.

. PMID 7212144. doi:10.2105/AJPH.71.5.530.

- ↑ "Fluzone". vaccineshoppe.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ Kark JD, Lebiush M, Rannon L (October 1982). "Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for epidemic a(h1n1) influenza in young men". The New England Journal of Medicine. 307 (17): 1042–6. PMID 7121513. doi:10.1056/NEJM198210213071702.

- ↑ "Influenza Strain Details for A/turkey/Ireland/?/1983(H5N8)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Diffusion of Influenza". amazon.com. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ Guo, YJ; Xu, XY; Cox, NJ (1992). "Human influenza A (H1N2) viruses isolated from China". The Journal of general virology. 73 (2): 383–7. PMID 1538194. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-383

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Nicholson KG, Kent J, Hammersley V (August 1999). "Influenza A among community-dwelling elderly persons in Leicestershire during winter 1993-4; cigarette smoking as a risk factor and the efficacy of influenza vaccination". Epidemiology and Infection. 123 (1): 103–8. PMC 2810733

. PMID 10487646. doi:10.1017/S095026889900271X.

. PMID 10487646. doi:10.1017/S095026889900271X.

- ↑ "History of Avian Influenza". extension.org. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Selleck, PW; Arzey, G; Kirkland, PD; Reece, RL; Gould, AR; Daniels, PW; Westbury, HA. "An outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza in Australia in 1997 caused by an H7N4 virus.". PMID 14575068. doi:10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.806.

- ↑ "FluNet". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Abgrall, Jean-Marie (2000). Healing Or Stealing?: Medical Charlatans in the New Age. Algora. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-892941-51-0.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Akey, BL. "Low-pathogenicity H7N2 avian influenza outbreak in Virgnia during 2002.". PMID 14575120. doi:10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.1099.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Geneviève, LD; Wangmo, T; Dietrich, D; Woolley-Meza, O; Flahault, A; Elger, BS. "Research Ethics in the European Influenzanet Consortium: Scoping Review.". PMC 6231872

Check

Check |pmc=value (help). PMID 10.2196/publichealth.9616 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Koppeschaar, CE; Colizza, V; Guerrisi, C; Turbelin, C; Duggan, J; Edmunds, WJ; Kjelsø, C; Mexia, R; Moreno, Y; Meloni, S; Paolotti, D; Perrotta, D; van Straten, E; Franco, AO. "Influenzanet: Citizens Among 10 Countries Collaborating to Monitor Influenza in Europe.". PMC 5627046

. PMID 28928112. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7429.

. PMID 28928112. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7429.

- ↑ Stegeman, A; Bouma, A; Elbers, AR; De Jong, MC; Nodelijk, G; De Klerk, F; Koch, G; Van Boven, M. "Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) epidemic in The Netherlands in 2003: course of the epidemic and effectiveness of control measures.". PMID 15551206. doi:10.1086/425583.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ The Global Strategy for Prevention and Control of H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Fauci AS (January 2006). "Pandemic influenza threat and preparedness". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (1): 73–7. PMC 3291399

. PMID 16494721. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050983.

. PMID 16494721. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050983.

- ↑ "Influenza Strain Details for A/Canada/rv504/2004(H7N3)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "EID Weekly Updates - Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, Region of the Americas". Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza". usda.gov. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Payungporn, Sunchai; Crawford, P. Cynda; Kouo, Theodore S.; Chen, Li-mei; Pompey, Justine; Castleman, William L.; Dubovi, Edward J.; Katz, Jacqueline M.; Donis, Ruben O. "Influenza A Virus (H3N8) in Dogs with Respiratory Disease, Florida". PMC 2600298

. PMID 18507900. doi:10.3201/eid1406.071270.

. PMID 18507900. doi:10.3201/eid1406.071270.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Shannon Brownlee and Jeanne Lenzer (November 2009) "Does the Vaccine Matter?", The Atlantic

- ↑ National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Whitehouse.gov Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ↑ "The International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza" (PDF). apec.org. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ "International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Ghedin E, Sengamalay NA, Shumway M, Zaborsky J, Feldblyum T, Subbu V, Spiro DJ, Sitz J, Koo H, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Tatusova T, Bao Y, St George K, Taylor J, Lipman DJ, Fraser CM, Taubenberger JK, Salzberg SL (October 2005). "Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution". Nature. 437 (7062): 1162–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1162G. PMID 16208317. doi:10.1038/nature04239

. (as PDF

. (as PDF

- ↑ "Influenza Strain Details for A/Cambodia/V0803338/2011(H1N1)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "The International Pledging Conference on Avian and Human Pandemic Influenza Is Successfully Held in Beijing".

- ↑ "flutrackers". flutrackers.com. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ↑ Dalton, Craig; Carlson, Sandra; Butler, Michelle; Cassano, Daniel; Clarke, Stephen; Fejsa, John; Durrheim, David. "Insights From Flutracking: Thirteen Tips to Growing a Web-Based Participatory Surveillance System". PMC 5579323

. PMID 28818817. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7333.

. PMID 28818817. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7333.

- ↑ "Global Action Plan for Influenza Vaccines (GAP)". who.int. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Overview of the 2007 Australian outbreak of equine influenza". Australian Veterinary Journal. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00721.x. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza (Biographies of Disease)". amazon.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Antivirals for Pandemic Influenza". nap.edu. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Avian Influenza". books.google.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Polozov, I. V.; Bezrukov, L.; Gawrisch, K.; Zimmerberg, J. (2008). "Progressive ordering with decreasing temperature of the phospholipids of influenza virus". Nature Chemical Biology. 4 (4): 248–255. PMID 18311130. doi:10.1038/nchembio.77.

- ↑ Robin Liechti1, Anne Gleizes, Dmitry Kuznetsov, Lydie Bougueleret, Philippe Le Mercier, Amos Bairoch and Ioannis Xenarios. "OpenFluDB, a database for human and animal influenza virus". doi:10.1093/database/baq004.

- ↑ Butler, Declan. "When Google got flu wrong". nature.com. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Europeans urged to avoid Mexico and US as swine flu death toll rises".

- ↑ "How vaccines became big business".

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Influenza Vaccine Composition". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza and Public Health: Learning from Past Pandemics". books.google.com.ar. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended viruses for influenza vaccines for use in the 2010-2011 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "WHO global technical consultation: global standards and tools for influenza surveillance 8–10 March 2011". who.int. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ↑ Karlsson, Erik A.; Hon, S.; Hall, Jeffrey S.; Yoon, Sun Woo; Johnson, Jordan; Beck, Melinda A.; Webby, Richard J.; Schultz-Cherry, Stacey. "Respiratory transmission of an avian H3N8 influenza virus isolated from a harbour seal". doi:10.1038/ncomms5791. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Standardization of terminology of the pandemic A(H1N1)2009 virus". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2011 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2011-2012 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Osterholm, MT; Kelley, NS; Sommer, A; Belongia, EA (January 2012). "Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 12 (1): 36–44. PMID 22032844. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(11)70295-x.

- ↑ "Scientists condemn 'crazy, dangerous' creation of deadly airborne flu virus".

- ↑ "Exclusive: Controversial US scientist creates deadly new flu strain for pandemic research".

- ↑ "U.S. virologists intentionally engineer super-deadly pandemic flu virus".

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2012 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza Virus: Methods and Protocols". books.google.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine manufactured using cell culture technology". fda.gov. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "Pandemic Influenza". books.google.com.ar. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2012-2013 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Avian and other zoonotic influenza". WHO. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Study says Vietnam at H7N9 risk as two new cases noted". umn.edu. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Radiology of Influenza: A Practical Approach". books.google.com.ar. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2013 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Flublok Quadrivalent Flu Vaccine". medscape.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Avian influenza A (H10N8)". WHO. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2013-14 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2014 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Vaccine, influenza". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. 2014.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2014-2015 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Real-time influenza tracking with 'big data'". eurekalert.org. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ Lazer, David; Kennedy, Ryan. "What We Can Learn From the Epic Failure of Google Flu Trends". wired.com. Science. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "Google Flu Trends". datacollaboratives.org. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2015 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2015-2016 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Tool for Influenza Pandemic Risk Assessment (TIPRA)". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2016 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2016-2017 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Researchers build flu detector that can diagnose at a breath, no doctor required". digitaltrends.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "Avian flu here; DA clears out 12,000 quails in Nueva Ecija farm". businessmirror.com.ph. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Certain anti-influenza compounds also inhibit Zika virus infection, researchers find". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "Influenza and Respiratory Care". books.google.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2017-2018 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2018 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2019 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2019-2020 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2020 southern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2020 - 2021 northern hemisphere influenza season". who.int. Retrieved 4 May 2020.