Timeline of Brookings Institution

This is a timeline of Brookings Institution, a United States group which conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in economics, metropolitan policy, governance, foreign policy, and global economy and economic development.[1]

Contents

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What are some landmark studies Brookings has conducted throughout its history?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Research".

- You might also be interested in the group of rows with value "Influence" -- although these are not directly about studies, they talk about ways these studies affected policy.

- What are some important books published by the institution?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Publication".

- You'll see a lot of rows, with the earliest being from 1919 (in Brookings' days as the Institute for Government Research). Note that most but not all publications are books.

- What are some programs launched by Brookings?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Program launch".

- You'll see a list of programs with description and launch year, starting from 1957 and going all the way to 2012.

- What are some important conferences held by Brookings?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Conference".

- You'll get a list of key conferences held by Brookings, along with the years they were held.

- How did leadership at Brookings change over time?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Leadership".

- You'll get information on the founder Robert Brookings as well as the various presidents Brookings has had and the years they served, starting with the first president Harold G. Moulton and going up to its current (as of 2019) president John R. Allen.

- How did Brookings react to historic events, like World War II or the September 11 attacks?

- Look at the rows in the big picture corresponding to the timeframe of the historic event, to get a big-picture sense.

- Look at the rows in the full timeline corresponding to the timeframe of the historic event, to learn more details. For instance, for the September 11 attacks, look at rows in the full timeline for 2001 in particular.

- What other think tanks and institutions has Brookings collaborated with in its lifetime?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Collaboration".

- You'll see names like Urban Institute, Hoover Institution, American Enterprise Institute, and Washington University in St. Louis

- What other notable think tanks rival Brookings?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Competition".

- You will see names like RAND Corporation and the United Nations University.

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Recognition (ranking)".

- You will see recent positions of Brookings among other think tanks on different rankings.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1916–1927 | Brookings prelude period, consisting in its predecessor Institute for Government Research (IGR), which is established as the first private organization devoted to analyzing public policy issues at the national level in the United States.[2] |

| 1930s | Brookings develops its own publishing division. In the 1930s, the organization is commissioned by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to do a large-scale study of the causes of the Great Depression.[3] |

| 1940s | During World War II, Brookings experts assist the United States Government on variety of issues, and study mobilization and issues connected to the planning of the United Nations. After the war, Brookings becomes heavily involved in the formulation of the organizational aspects of the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan).[3] |

| 1950s | Brookings capacity to shape government policy increases dramatically in the decade, when it receives substantial grants from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations.[4] |

| 1960s | By the mid-decade Brookings conducts nearly 100 research projects per year for the government as well as for private industry, making it a preeminent source of research at a worldwide scale.[4] |

| 1970s | Throughout the decade, Brookings is offered more federal research contracts than it can handle.[5] |

| 1980s | Brookings is exposed to increasingly competitive and ideologically charged intellectual environment.[6] The need to reduce the federal budget deficit becomes a major research theme in the 1980s, as well as investigating problems with national security and government inefficiency. The Center for Public Policy Education is established to develop workshop conferences and public forums to broaden the audience for research programs.[7][8] |

| 1990s | The Federal government of the United States devolves many of its social programs back to cities and states, and Brookings shapes a new generation of urban policies to help build strong neighborhoods, cities and metropolitan regions.[2] |

| 2000s | After the September 11 attacks, Brookings experts produce influential proposals for homeland security and intelligence operations. The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and the Center for Middle East Policy are established. Brookings also expands outside the United States with the openings of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center in Beijing, and the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar. |

| 2010s | Brookings stands among the most prestigious and most frequently cited think tanks. The University of Pennsylvania's Global Go To Think Tank Index Report names Brookings "Think Tank of the Year" and "Top Think Tank in the World" every year since 2008.[9] |

Visual data

Wikipedia pageviews

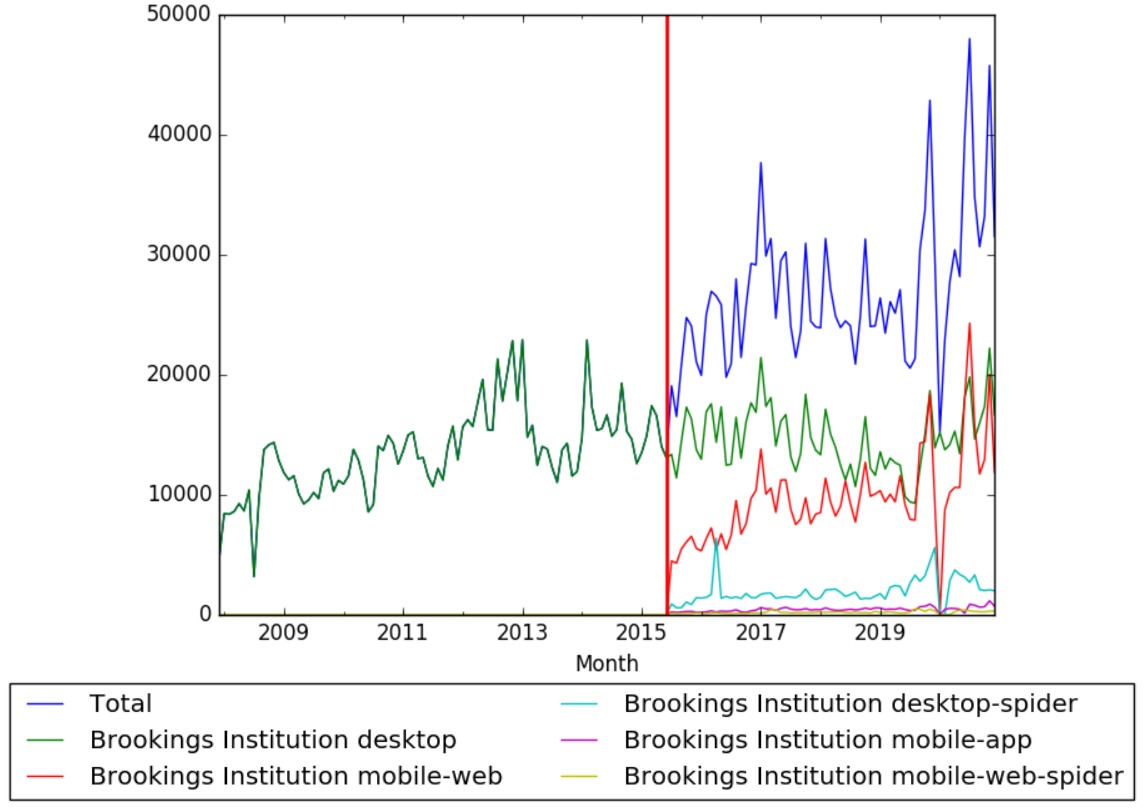

The chart below shows Wikipedia views of the page Brookings Institution on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from June 2015 to January 2021.

The red vertical line (for July 2015) represents the start of mobile–web and mobile–app data retrievals.

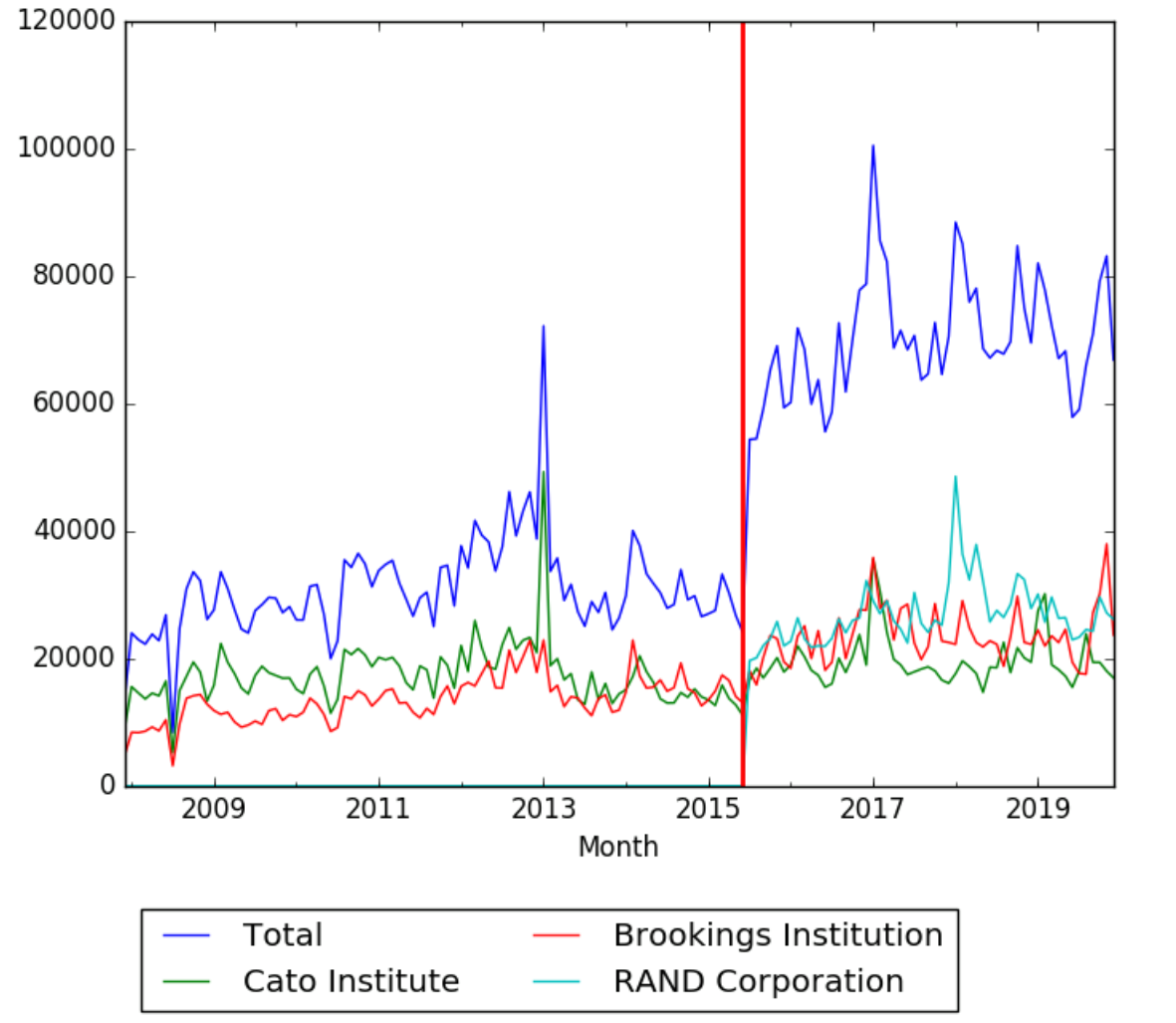

The image below shows comparison of Wikipedia pageviews for Brookings Institution, the RAND Corporation, and Cato Institute.[10]

Google Trends

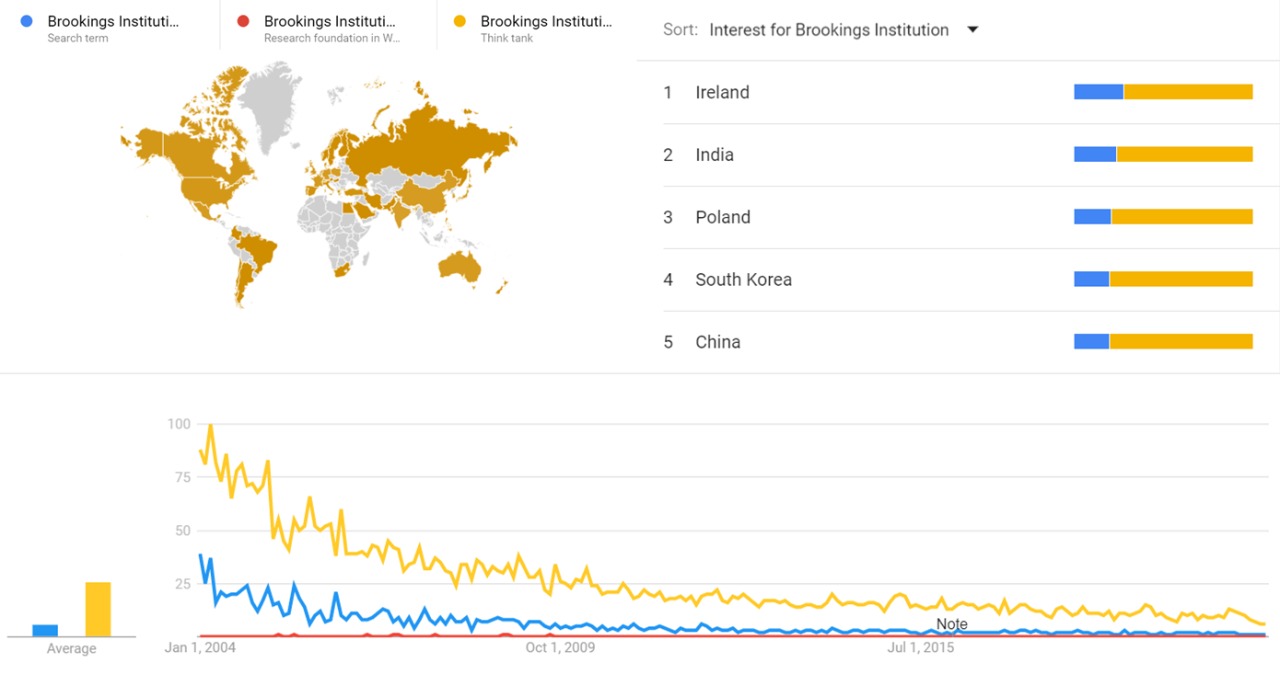

Google Trends data for Brookings Institution from January 1 2004 to January 13 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[11]

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | Early development | In Washington, D.C. a group of leading educators, businessmen, attorneys, and financiers, including businessman and philanthropist Robert S. Brookings, found the Institute for Government Research (IGR), with the mission of becoming "the first private organization devoted to analyzing public policy issues at the national level."[12] IGR becomes the first private organization devoted to bettering the practices and performance of government with recommendations generated by outside experts. Its first research project, directed by economist William Willoughby, focuses on helping the Bureau of Internal Revenue revise the reporting of tax statistics for greater accuracy.[13][2] | |

| 1917 | Leadership | Robert Brookings is appointed by United States President Woodrow Wilson to the War Industries Board, a government agency which coordinates the purchase of military supplies. Later, Brookings is made chairman of the board’s Price Fixing Committee, to discourage profiteering.[13] | |

| 1919 | Publication | IGR publishes A National Budget System: the Most Important of all Governmental Reconstruction Measures.[13] | |

| 1921 | Influence | Landmark legislation Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 is crafted and passed with the lead of IGR recommendations. The legislation expands executive power in the federal budget process. President Warren Harding calls it “the beginning of the greatest reform in governmental practices since the beginning of the republic.”[13][2] | |

| 1921 | Competition | The Council on Foreign Relations is established.[14] Today it is considered a top Brookings competitor.[15] | |

| 1922 | Institutional | IGR establishes the Institute of Economics, for the “sole purpose of ascertaining the facts about current economic problems and of interpreting these facts for the people of the United States.” Chicago University economist Harold G. Moulton is named its director.[13][2] | |

| 1923 | Research | Harold G. Moulton and staff economist Constantine McGuire write of post-Great War Europe that “the reparation situation has gone from very bad to worse.” The report examines the ability of Germany and its allies on the losing side of World War I to pay the debts mandated by the Versailles Treaty.[13] | |

| 1923 | Collaboration | IGR partners with Washington University in St. Louis to provide training in public service and establish the Robert S. Brookings Institute of Economics and Government for Teaching and Research (later the Robert S. Brookings Graduate School of Economics and Government). Between 1924 and 1930, 74 PhDs would be awarded by the school.[13] | |

| 1927 | Merger | IGR merges with its recently created sister organizations, the Institute of Economics and the Robert Brookings Graduate School of Economics and Government, to form the Brookings Institution, named after Robert Brookings in recognition of his services to all three organizations. Its mission: “to promote, carry on, conduct and foster scientific research, education, training and publication in the broad fields of economics, government administration and the political and social sciences generally.”[13][2] | |

| 1927 | Leadership | The Brookings Trustees choose their first president: American economist Harold G. Moulton, who was previously director of the Institute of Economics and a member of the boards of the Graduate School and the Institute for Government Research.[13][2] | |

| 1928 | Research | United States Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work commissions IGR’s Lewis Meriam to undertake a comprehensive survey of the condition of Native Americans. The resulting report, titled The Problem of Indian Administration (known as Meriam Report) becomes influential in shaping American Indian affairs policies in the Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt administrations.[16][17][18] | |

| 1928 | Institutional | Brookings begins its own in-house publishing division, which precedes the Brookings Institution Press.[13] | |

| 1932 | Leadership | Robert Brookings dies in Washington, D.C. at the age of 82. His book The Way Forward is published just before his death, in which Brookings calls for the more equal distribution of wealth.[13] | |

| 1934 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes the two first volumes of the four works titled The Distribution of Wealth and Income in Relation to Economic Progress (informally known as the “capacity studies”). The first volume is entitled America’s Capacity to Produce, the second, and the second America’s Capacity to Consume. The works focus on production and consumption capacity, capital, and market speculation in the 1920s. These studies would become a major guide to the United States economy for policymakers for much of the decade.[19] | |

| 1935 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes the two last volumes of the four works titled The Distribution of Wealth and Income in Relation to Economic Progress: The Formation of Capital and 'Income and Economic Progress. These two volumes are authored by Harold G. Moulton alone.[19] | |

| 1935 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a detailed analysis of the National Recovery Administration NRA, which was established by president Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. The authors conclude that the NRA impeded economy recovery after the Depression.[20][13] | |

| 1938 | Competition | The American Enterprise Institute is founded. It is considered one of Brookings's top rivals.[15] | |

| 1939 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes Reorganization of the National Government—What Does it Involve?, in which scholars and Lewis Meriam and Laurence F. Schmeckebier shed light on President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Reorganization Act of 1939, which permitted the president to reorganize certain aspects of the executive branch and created the Executive Office of the President.[21] | |

| 1939 | Assistance | World War II begins. Brookings experts recommend policies on a variety of issues, including wartime price controls, military mobilization, German and U.S. manpower requirements, and later, postwar demobilization and preventing Germany and Japan from re-arming.[13] | |

| 1941 | Research | A study by scholar Laurence Schmeckebier at Brookings Institution develops the system of apportioning congressional representation among the states that would become embodied in the Congressional Apportionment Act of 1911.[13] | |

| 1941 | Assistance | The United States enter into World War II. Brookings researchers turn their attention to aiding the administration with a series of studies on mobilization.[22] | |

| 1944 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a study by Joseph Mayer on Post-War National Income, Its Probably Magnitude.[23] | |

| 1946 | Leadership | Economist Leo Pasvolsky becomes first director of the International Studies Group at Brookings, which conducts research and education in international relations and is the precursor to what would become the Foreign Policy program at Brookings.[13] | |

| 1947 | Research | Brookings scholars conduct a study of compulsory health insurance, which concludes that a national health insurance program would be too political, too expensive, and too detrimental to the nation’s economic health. Two proposals emerge: grants-in-aid to states that will ensure quality medical attention for those who need it; and the formation of a compulsory health insurance program by the national government.[13] | |

| 1948 | Assignment | The Brookings Institution is asked by the United States Government to draft a proposal on how to manage the European Recovery Program Marshall Plan. The resulting organization scheme assures that the Marshall Plan is run carefully and on a businesslike basis.[22] Brookings experts play a pivotal role in the development of the program, providing valuable recommendations on the administrative organization.[13] | |

| 1948 | Recognition | United States Senator Arthur Vandenberg praises Brookings for a report on post-war Europe assistance that would become “the Congressional ‘work-sheet’ in respect to this complex and critical problem.”[2] | |

| 1948 | Competition | The RAND Corporation is founded.[24] It is one of the top Brookings competitors. Whereas Brookings is funded by a mix of endowment and donor money, with individual scholars deciding their own major research projects, RAND is a Federally Funded Research and Development Center, a think tank directly supported by the Federal government of the United States.[25] | |

| 1949 | Research | Experts at Brookings conduct research that forms the basis of a task force report on public welfare, prepared for the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government (also known as the Hoover Commission).[13] | |

| 1949 | Publication | Charles Dearing and Wilfred Owen at Brookings publish National Transportation Policy, which recommends the creation of a new department of transportation headed by a new cabinet secretary.[13][26] | |

| 1950 | Publication | Scholars Lewis Meriam and Karl Schlotterbeck at Brookings publish The Cost and Financing of Social Security, which weighs in on legislation to change social security programs, arguing for a pay-as-you-go system.[13] | |

| 1952 | Leadership | Economist and educator Robert Calkins becomes the second president of the Brookings Institution.[13] | |

| 1952 | Research | The Brookings Institution conducts a landmark study of share ownership on behalf of the New York Stock Exchange. The survey shows that 6.5 million Americans (4 percent of the overall population), own stock directly.[27] | |

| 1953 | Research | Leo Pasvolsky at Brookings initiates a series of studies on the United Nations looking at the features of the UN system to provide a better public understanding of its capabilities and limitations. The studies are published after his death in the same year.[13] | |

| 1954 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes Industrial Pensions by Charles L. Dearing, the research for which was begun shortly after the Inland Steel Company decision in 1949, which made pensions a bargainable subject under the Taft–Hartley Act. The study includes a survey as of 1950 of the plans of 412 companies employing 4,000,000 workers, reflecting costs and funding arrangements as well as benefit features.[28] | |

| 1957 | Program launch | Brookings President Robert Calkins leads a new program of education for senior government executives. The program contributes to passage of the Federal Training Act of 1958 that provides across-the-board federal employee training to improve government productivity.[13] | |

| 1957 | Administration | The United States Government uses eminent domain to take over Brookings’s Jackson Place headquarters. Brookings headquarters move from Jackson Avenue to a new research center near Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C.[29][13] | |

| 1959 | Publication | Marshall Robinson at Brookings publishes The National Debt Ceiling: An Experiment in Fiscal Policy, which argues that the debt ceiling has not only failed, but backfired. The study would be quoted in congressional debates during the 1960s, and again in 2013.[13] | |

| 1960 | Publication | Brookings scholar Laurin Henry publishes Presidential Transitions, which would remain an influential and often-cited work on the history of presidential transitions.[30] The book is followed by a series of confidential issues papers prepared by Brookings experts.[13] | |

| 1960 | Research | The Brookings Institution makes its second major study of overseas operations.[31] | |

| 1960 | Program launch | The Brookings Institution begins a four-year program with the Ford Foundation and the Government of South Vietnam to provide assistance in tax policy, fiscal policy, and economic planning to the national government in Saigon down to provinces and villages.[13] | |

| 1960 | Publication | Brookings experts publish Proposed Studies on the Implications of Peaceful Space Activities for Human Affairs, preparing a report for NASA and giving advice to the New Space Program. The authors make dozens of recommendations for additional studies on the social, economic, political, legal, and international implications of the use of space.[13] | |

| 1960 | Publication | Brookings governmental studies expert Laurin L. Henry publishes Presidential Transitions, designed to help the winning candidate (John F. Kennedy or Richard M. Nixon) launch his administration smoothly. The book is followed by a series of confidential issues papers prepared by Brookings experts.[2] | |

| 1961 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a book by American economist Alice Rivlin entitled The Role of the Federal Government in Financing Higher Education.[32] | |

| 1962 | Publication | Brookings scholar John Lewis publishes The Quiet Crisis in India, which studies India's rural development. Lewis makes the case for aid to India and the developing world as a component of U.S. foreign policy.[33] | |

| 1963 | Program launch | Brookings Foreign Policy and Governmental Studies programs, in conjunction with several Latin American research organizations, coordinate a program of studies on trade and investment policies in Latin America that would last into the early 1980s. The program would be said to have strengthened the economics profession in Latin America.[13] | |

| 1963 | Conference | The Brookings Institution in Washington holds a conference on "quantitative planning of economic policy". Speakers (which in clude Dutch and French representatives) present their models.[34] | |

| 1963 | Proposal | The Brookings Institution advocates a shared federal library storage facility in its report Federal Departmental Libraries: A Summary Report of a Survey and a Conference. The authors suggest that such a facility could be a “cheap storage building, perhaps in a mountainside near Washington”. Major federal libraries would contribute to the management and administration on a cooperative basis, and requested materials would be delivered within a day. The imagined facility would maintain brief catalog entries that would be provided to cooperating libraries.[35] | |

| 1965 | April 7 | Leadership | Isabel Vallé Brookings, wife of Robert S. Brookings, dies aged 89, and leaves the Institution an US$8 million bequest.[13] |

| 1965 | Research | The Brookings Institution creates a task force to study bankruptcy administration.[36] | |

| 1965 | Conference | The Brookings Institution holds a conference to address the major problems of intergovernmental finance and to propose solutions to those problems.[37] | |

| 1966 | Institutional | The Brookings Institution enters the compuer age by establishing the Social Science Computation Center for Research, which offers computational research support for scholars, including use of a mainframe computer.[13] | |

| 1966 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a book by Charles Frankel entitled The Neglected Aspect of Foreign Affairs. Frankel argues that “in comparison with the sophisticated analysis devoted to U.S. military, economic, and diplomatic policy, little intellectual attention has been given to international cultural exchange”.[38] | |

| 1967 | Leadership | Kermit Gordon becomes the third president of Brookings. Gordon previously served as the director of the United States Bureau of the Budget.[2] | |

| 1967 | Program launch | The Brookings Institution launches a major initiative on the economic impact of regulation, backed by US$1.8 million from the Ford Foundation and directed by a panel that includes George Stigler.[39] | |

| 1968 | Publication | Brookings publishes the first in a series of Agenda for the Nation volumes, which are collections of papers on domestic and foreign policy issues.[13] | |

| 1969 | Program launch | Under the leadership of Kermit Gordon and Foreign Policy Program Director Henry Owen, Brookings establishes the Defense Analysis Project to study issues such as defense support costs and the force structures of the United States, NATO, and Soviet Union. Work from the project would become influential among congressional decision-makers.[13] | |

| 1970 | Publication | American economist Arthur Melvin Okun and George Perry at Brookings introduce the first edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, which remains a highly influential and respected economics journal.[13] | |

| 1971 | Research | Experts at Brookings begin a new series of studies on the federal budget and congressional spending choices. These studies would eventually lead to the creation of the Congressional Budget Office.[13] | |

| 1971 | Publication | Brookings releases the first report in the Setting National Priorities series, a cross-program initiative focused on evaluating annual White House budgets as they are released and examining the domestic and foreign policy choices that confront the United States. These series would become highly acclaimed and influential.[13] | |

| 1972 | Publication | Brookings publishes a study which critically examines evidence regarding the popular assumption that poor people stay on welfare out of dislike for work. The findings indicate that welfare recipients internalize the same positive norms and values that dominate the cultural orientations toward work.[40] | |

| 1972 | December | Competition | The United Nations University is established.[41][42] It is considered among the top Brookings competitors.[15] |

| 1973 | Conference | The Brookings Institution holds a conference on variation of the Head Start program (launched in 1965) and presents a program for planned variation studies development.[43] | |

| 1977 | Competition | The Cato Institute is founded. It is one of Brookings's top competitors.[15] | |

| 1974 | Research | The Brookings Institution declares that the after-tax profit rate for United States corporations has fallen since 1948, from just under eight percent to just under five percent.[44] | |

| 1975 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a little book by Arthur Melvin Okun entitled Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff, which would consideded a classic in its field. The book explores “the big tradeoff” between society’s desire to reduce inequality and the risk of impairing economic efficiency. It also examines how redistributing income affects economic growth.[13][45] | |

| 1975 | Assistance | Following the Yom Kippur War, Brookings releases recommendations of the Middle East Study Group, an assembly of Americans tasked with considering how the United States might help in the achievement of a workable, fair, and enduring settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict.[13] | |

| 1976 | Leadership | Gilbert Y. Steiner is elected as acting president of the Brookings Institution.[2] | |

| 1976 | Publication | Stephen H. Hess at Brookings publishes Organizing the Presidency, which examines how various presidents have organized their offices and staff and "sheds light on how the presidency has become an institution unto itself".[13] | |

| 1976 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes Asia's New Giant, an extensive analysis by a team of US and Japanese social scientists that explains Japan's extraordinary economic performance over the previous twenty-five years.[46] | |

| 1977 | Leadership | Bruce MacLaury is named fourth president of the Brookings Institution.[2] Previously, MacLaury served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.[13] "Fourth President Comes to Brookings. The Board of Trustees names Bruce MacLaury the fourth president of Brookings. Before coming to Brookings, he served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis."[13] | |

| 1978 | July 1 | Publication | Brookings publishes Arms across the sea, by Philip J Farley, Stephen S. Kaplan and William H. Lewis. The book explores the Soviet military power.[47] |

| 1978 | Publication | Brookings researcher Gary Orfield publishes Must We Bus? Segregated Schools and National Policy, which argues that American schools have a legal and moral obligation to practice desegregation busing. Orfield calls out school and government officials for intentionally dragging their feet through this process and asserts that more must be done to achieve the goal of desegregation than simply busing students to different schools.[13][48] | |

| 1979 | Publication | Leslie H. Gelb research associate Richard Betts at Brookings conclude in a study of the United States role in Vietnam that while the foreign policy outcome of the U.S. involvement was a failure, the decision-making system worked as designed. Yale University historian Gaddis Smith would write that “If an historian were allowed but one book on the American involvement in Vietnam, this would be it.”[13] | |

| 1980 | Publication | Norman Ornstein from American Enterprise Institute and Thomas E. Mann at Brookings jointly publish Vital Statistics on Congress, detailing the election and composition of the United States Congress membership, party structure, and staff. Mann and Ornstein also document the growing partisan divide in Congress and track the demographics of senators and representatives. The book would be published entirely online in 2013.[13] | |

| 1981 | Conference | The Brookings Institution and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences begin a series of joint-venture conferences participated in by government officials, leaders in the public and private sectors, and scholars from the United States and China.[49] | |

| 1981 | Research | The Brookings Institution commissions a series of studies on the economic consequences of aging and on the effects of public and private programs that aid the aged.[50] | |

| 1981 | Competition | The Peterson Institute for International Economics is established.[51] It is considered among the top Brookings competitors.[15] | |

| 1982 | Conference | The Brookings Institution decides to hold a symposium to discuss the impact of abortion politics on U.S. politics.[52] | |

| 1982 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a book titled Urban Decline and the Future of American Cities.[53] | |

| 1982 | Research | The Brookings Institution finds that 62 percent of an average firm’s value could be related to its physical assets (e.g., equipment, technologies), with only 38 percent attributed to intangible assets (e.g., patents, intellectual property, brand, and, most of all, people). However, after 21 years in 2003, these percentages would reverse, with 80 percent of value linked to intangible assets and just 20 percent related to tangible assets.[54] | |

| 1984 | Publication | Sidney Weintraub at Brookings publishes Free Trade between Mexico and the United States?, which analyzes the pathologies existing at the time in the highly restricted bilateral trade between the two countries, and examines the foregone opportunities that a trade opening would likely provide and, as the book’s title implies, recommends a bilateral trade agreement between them.[55] | |

| 1985 | Publication | Brookings releases Paul Peterson's The New Urban Reality, which states that the twin issues of technology and race argue against further investments in the central city.[56] | |

| 1986 | Research | Research by Brookings Senior Fellow Joseph A. Pechman leads to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, a major bill that would have a profound impact on the economy of the United States.[2] The act is designed to simplify the tax code, broaden the tax base, and eliminate many tax shelters and preferences.[57] Pechman’s Federal Tax Policy is essential to those reforms.[13] | |

| 1987 | Institutional | The Brookings Institution forms the Center for Economic Progress and Employment which focuses on productivity growth, poverty, and related issues.[58] | |

| 1989 | Research | At the suggestion of Senator Joseph Biden, the Brookings Institution convenes a task force to study delay and cost in federal civil litigation. The task force recommends a series of case-management strategies designed to streamline the process and to attack discovery abuse. Biden would incorporate these case-managementre commendations into the legislation introduced as the Civil Justice ReformAct of 1990.[59] | |

| 1989 | Program launch | The Brookings Institution and the Grupo de Análisis para el Desarrollo (GRADE), an independent research organization in Lima, launch a project to design a program to stabilize the economy of Peru and provide for the structural adjustments needed to ensure a strong recovery.[60] | |

| 1990 | Publication | John E. Chubb and Terry M. Moe at Brookings publish Politics, Markets, and America's Schools, which examines the growing dissatisfaction with the school system in the United States. They propose a new system of public education constructed around competition among schools, parent-student choice, and agency within the system.[13] | |

| 1992 | Publication | Norman Ornstein from American Enterprise Institute and Thomas E. Mann at Brookings publish reports from the Renewing Congress Project, which focuses on ways to improve congressional debate and action on legislation, enhance relationships between parties, and fix the campaign finance system. Their work makes a significant contribution to the debate about congressional reform.[13] | |

| 1992 | December 21 | Online management | brook.edu domain record is activated.[61]

|

| 1993 | Publication | The Brookings Institution publishes a landmark study by three professors from Tufts University, which examines five cities that characterize the most impressive commitment to the idea of participatory democracy through the development of a citywide network of neighborhood associations that brought government closer to the people: Saint Paul, Minnesota, Portland, Birmingham, Alabama, Dayton, and San Antonio, Texas.[62] | |

| 1994 | Publication | Brookings Senior Fellow Raymond L. Garthoff authors The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War, which shows that the United States did not win the Cold War with President Reagan’s military buildup, but instead, “‘victory’ came when a new generation of Soviet leaders realized how badly their system at home and their policies abroad had failed.”[13] | |

| 1994 | Publication | Anthony Downs at Brookings authors New Visions for Metropolitan America, which discusses the problem of rapid expansion of cities and suburban areas. In 1998, Bruce Katz’s “Reviving Cities: Think Metropolitan,” examines problems caused by explosive urban sprawl and emphasizes the necessity of a federal metropolitan agenda. Katz later becomes founding director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings."[13] | |

| 1995 | Website launch | Brookings launches its website, located at www.brook.edu.[13]

| |

| 1995 | Leadership | Foreign Policy Veteran Michael Armacost becomes the fifth president of Brookings.[13][2] | |

| 1995 | Publication | Brookings scholar Susan Woodward publishes Balkan Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution After the Cold War, which studies the impact of collapsing state authority and worsening economic conditions in triggering the Breakup of Yugoslavia.[13] | |

| 1996 | September 7 | Online management | brookings.edu domain record is activated.[63]

|

| 1996 | Publication | Brookings scholars Joshua M. Epstein and Robert Axtell publish Growing Artificial Societies which applies agent-based computer modelling in their groundbreaking study of human social interactions. The authors model an artificial society “from the bottom up” that can account for evolutionary change.[13] | |

| 1997 | Recognition (ranking) | Brookings ranks as the first-most influential and first in credibility among 27 think tanks considered in a survey of congressional staff and journalists.[64] | |

| 1998 | Publication | Francis Deng and Roberta Cohen at Brookings publish Masses in Flight: The Global Crisis of Internal Displacement, which analyzes the causes and consequences of internal displacement. The book is called “a landmark study” by diplomat Richard Holbrooke.[13] | |

| 1999 | Research | Brookings surveys 1,000 college professors in the United States, asking them to identify the U.S.' most important accomplishments in the past 100 years. The Marshall Plan is ranked N°1, as the greatest public policy of the past century.[65] | |

| 2000 | Collaboration | The Brookings Institution, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Hoover Institution jointly conduct several forums with journalists and the presidential candidates' close associates that explore how each of the candidates would govern based on their backgrounds, experience, and leadership styles.[66] | |

| 2001 | Research | Political scientist Ron Haskins and economist Isabel Sawhill at Brookings, team to study the United States policies on children and families. A proposal by Sawhill and researcher Adam Thomas for a child tax credit becomes part of major tax legislation.[2] | |

| 2001 | Institutional | Exactly one week before the September 11 attacks, Brookings’s TV and radio studio opens for business. The first live television feed occurs on the afternoon of 9/11 with CNN.[13] | |

| 2001 | Assistance | After the September 11 attacks, with remarkable speed, Brookings experts produce influential proposals for homeland security and intelligence operations.[2] Protecting the American Homeland is published on October 25.[67][13] | |

| 2001 | Proposal | Brookings scholar Isabel Sawhill writes a proposal that would help forge bi-partisan support in Congress to extend the benefits of the child tax credit in the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 to lower- and middle-income families.[13] | |

| 2002 | January 9 | Institutional | Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center is founded. A nonpartisan[68] think tank based in Washington D.C.[69], it is a joint venture of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution, aiming to provide independent analyses of current and longer-term tax issues, and to communicate its analyses to the public and to policymakers.[70] |

| 2002 | Leadership | American foreign policy analyst Strobe Talbott becomes the sixth president of Brookings.[13][71][2] | |

| 2002 | Institutional | Brookings establishes the Center for Middle East Policy "to promote a better understanding of the policy choices facing American decision makers in the Middle East".[72] | |

| 2003 | Recommendation | Led by former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker, the second National Commission on the Public Service (a project of a Brookings policy center) releases a set of recommendations for government reform, entitled Urgent Business for America. The Commission offers rationales and ideas for reorganizing the federal government that stem from the work of the center.[13] | |

| 2003 | Publication | A joint effort between Brookings and the American Enterprise Institute issues The Continuity of Congress, the first of a set of reports on how to carry on the functions of government in the event of a massive and catastrophic attack on the main institutions of the United States Government.[13] | |

| 2004 | Influence | Brookings scholars William Gale, Mark Iwry, and Peter Orszag attempt to influence legislation by making the case that helping Americans save for retirement requires financial incentives for low- and middle-income workers coupled with new corporate practices to make saving easier.[13] | |

| 2004 (July 6) | Renaming | The Brookings Institution announces that the former Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy (founded in 1966) would become the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program.[73][13] | |

| 2006 | International expansion | Brookings establishes in Beijing the Brookings-Tsinghua Center (BTC) for Public Policy as a partnership between the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC and Tsinghua University's School of Public Policy and Management in Beijing. The Center seeks to produce research in areas of fundamental importance for China's development and for US-China relations.[74] The BTC is directed by Qi Ye.[75] | |

| 2006 | Program launch | Brookings' Global Economy and Development program is founded. The program aims "to shape the policy debate on how to improve global economic cooperation and fight global poverty and sources of social stress."[13][76] | |

| 2006–2007 | Assistance | Brookings scholars provide analysis and recommendations throughout the Iraq War. Michael O’Hanlon, William Quant, and Shibley Telhami at Brookings, participated in the Iraq Study Group in 2006, which recommends an increase in U.S. combat troops in Iraq that occurs in 2007.[13] | |

| 2008 | International expansion | The Brookings Doha Center is established in Doha as an overseas center of the Brookings Institution.[77] | |

| 2008 | Recognition (ranking) | The University of Pennsylvania 2008 think tank survey ranks Brookings first in the world by research area, health policy, security and international affairs, domestic economic policy, international economic policy, and social policy. It is ranked second in environment and Think Tanks with the most innovative policy/idea proposal.[78] | |

| 2009 | December | Recognition | United States President Barack Obama chooses Brookings as the venue for announcing his plan for creating jobs and spurring economic growth.[13] |

| 2009 | Publication | The Brookings' Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform report Bending the Curve: Effective steps to address long-term healthcare spending growth is published. It would become widely credited as being the most constructive contribution to the conversation on addressing long-term growth in health care spending.n[13] | |

| 2009 | Proposal | Scholars Warwick McKibbin, Adele Morris, and Peter Wilcoxen at Brookings recommend how carbon price agreements can strengthen international emissions targets.[13] | |

| 2009 | Publication | A joint effort between Brookings and the American Enterprise Institute issues The Continuity of the Presidency, the second of a set of reports on how to carry on the functions of government in the event of a massive and catastrophic attack on the main institutions of the United States Government.[13] | |

| 2009 | Assistance | Brookings experts contribute with ideas on how best to recover from the Great Recession with a steady stream of analysis and recommendations on fiscal and monetary stimulus plans, as well as the automotive and banking bailouts.[13] | |

| 2010 | Collaboration | Brookings expert and former United States Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice, serves as an editor for the book Confronting Poverty: Weak States and U.S. National Security, which highlights how the effects of poverty in fragile states can spill over borders and threaten U.S. national security.[13] | |

| 2011 | Publication | E.J. Dionne and William Galston at Brookings play an influential role with their report A Half-Empty Government Can't Govern, which informs the United States Senate the passage of the Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011, which becomes law in the same year.[13] | |

| 2011 | Collaboration | A joint effort between Brookings and the American Enterprise Institute issues The Continuity of the Supreme Court, the third of a set of reports on how to carry on the functions of government in the event of a massive and catastrophic attack on the main institutions of the United States Government.[13] | |

| 2012 | Publication | Brookings scholar Carol Graham publishes Happiness around the World: The Paradox of Happy Peasants and Miserable Millionaires, in which she studies happiness across developed and developing countries.[13] | |

| 2012 | Program launch | The Brookings Institution launches the Global Cities Initiative as a joint project with JPMorgan Chase. The five-year project aims to help leaders in U.S. metropolitan areas reorient their economies toward greater engagement in world markets.[13] | |

| 2012 | Competition | The Center on Global Interests is founded.[79] It is considered among the top Brookings competitors.[15] | |

| 2013 | Assistance | Experts at Brookings assist on the development of the next generation of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, contributing to their mission to improve the lives of people worldwide.[13] | |

| 2013 | Recognition (ranking) | The University of Pennsylvania 2013 think tank survey ranks Brookings first in the world.[80] | |

| 2013 | International expansion | Brookings opens in India its third overseas office, the New Delhi Center. Organized and staffed in large part by Indian nationals, it serves as a platform for relevant and productive research centered on India’s changing role in the world.[13][81][82] | |

| 2014 | Recognition (ranking) | The University of Pennsylvania 2014 think tank survey ranks Brookings first in the world.[83] | |

| 2015 | Collaboration | The Brookings' Center for Universal Education joins the Michelle Obama's initiative Let Girls Learn, which aims at helping adolescent girls attain "a quality education that empowers them to reach their full potential".[13] | |

| 2015 | Influence | United States President Barack Obama promotes the Automatic IRA to increase workers' retirement security. The idea originates in research by the Retirement Security Project at Brookings.[13] | |

| 2017 | October | Leadership | Former general John R. Allen becomes the seventh president of Brookings.[84][2] |

| 2017 | Financial | Brookings reports assets of US$524.2 million.[85] | |

| 2018 | September 18 | Recognition (ranking) | thebestschools.org ranks Brookings 7th on its list of The 50 Most Influential Think Tanks in the United States, after Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, The Earth Institute, The Heritage Foundation, Human Rights Watch, Kaiser Family Foundation, and Council on Foreign Relations.[86]

|

| 2019 | December | Recognition (ranking) | Bibliographic database IDEAS ranks Brookings Institution 6th on its list of Top 25% Think Tanks, after the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics (IIE), and the Ifo Institute for Economic Research (ifo Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung).[87] |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "Brookings Institution". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 "BROOKINGS INSTITUTION HISTORY". brookings.edu. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Folly, Martin; Palmer, Niall. The A to Z of U.S. Diplomacy from World War I through World War II.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Brookings Institution (BI)". discoverthenetworks.org. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ↑ "Brookings History: National Doubts and Confusion". Archived from the original on August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Easterbrook, Gregg (1986-01-01). "Ideas Move Nations". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Brookings History: Setting New Agendas". Archived from the original on July 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Bruce K. MacLaury". federalreservehistory.org.

- ↑ "TTCSP GLOBAL GO TO THINK TANK INDEX REPORTS". UPenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania. 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Overall comparison of Wikipedia pageviews". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ "Brookings Institution". trends.google.com. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ "Brookings Institution". brookings.edu. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 13.27 13.28 13.29 13.30 13.31 13.32 13.33 13.34 13.35 13.36 13.37 13.38 13.39 13.40 13.41 13.42 13.43 13.44 13.45 13.46 13.47 13.48 13.49 13.50 13.51 13.52 13.53 13.54 13.55 13.56 13.57 13.58 13.59 13.60 13.61 13.62 13.63 13.64 13.65 13.66 13.67 13.68 13.69 13.70 13.71 13.72 13.73 13.74 13.75 13.76 13.77 "A CENTURY OF IDEAS". brookings.edu. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ↑ "Council on Foreign Relations". jstor.org. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 "Brookings's Competitors, Revenue, Number of Employees, Funding and Acquisitions". owler.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ Lawson, Russell M. Encyclopedia of American Indian Issues Today [2 volumes].

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Native American Legal Tradition (Bruce Elliott Johansen ed.).

- ↑ Szasz, Margaret. Education and the American Indian: The Road to Self-determination Since 1928.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Brookings's analysis and recommendations on the Great Depression of the 1930s". brookings.edu. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ Hurtgen, James R. The Divided Mind of American Liberalism.

- ↑ "Reorganization of the National Government—What Does it Involve? By Lewis Meriam and Laurence F. Schmeckebier. (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. 1939. Pp. 272. $2.00.)". doi:10.2307/1948805. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Brookings History: War and Readjustment". Archived from the original on July 12, 2007.

- ↑ Railroad Retirement: Hearings Before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, House of Representatives, Seventy-ninth Congress, First Session on H.R. 1362, a Bill to Amend the Railroad Retirement Acts, the Railroad Unemployment Insurance Act, and Subchapter B of Chapter 9 of the Internal Revenue Code, and for Other Purposes (United States. Congress ed.).

- ↑ "A Brief History of RAND". rand.org. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ "Washington's Think Tanks: Factories to Call Our Own". brookings.edu. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ "1948 REPORT OF THE HOOVER COMMISSION TASK FORCE ON TRANSPORTATION". enotrans.org. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ↑ Reamer, Norton; Downing, Jesse. Investment: A History.

- ↑ "LERA Communities".

- ↑ "Brookings History: Academic Prestige". Archived from the original on August 14, 2007.

- ↑ "What Brookings did for the 1960 presidential transition". brookings.edu. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Harr, John Ensor. The Professional Diplomat.

- ↑ Higher Education: A Bibliographic Handbook, Volume 1 (D. Kent Halstead ed.).

- ↑ Staley, Eugene. "Quiet Crisis in India. Economic development and American policy. John P. Lewis. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., 1962. xiv + 350 pp. $5.75". science.sciencemag.org. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ "Monographs of official statistics" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ "SHARING A FEDERAL PRINT REPOSITORY: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES" (PDF). loc.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ An Evaluation of the U.S. Trustee Pilot Program for Bankruptcy Administration: Findings and Recommendations. Executive Office for U.S. Trustees.

- ↑ Monthly Labor Review, Volume 104, Issues 7-12.

- ↑ "The Power of Cultural Diplomacy – Why does the United States Neglect It?". publicdiplomacycouncil.org. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ Appelbaum, Binyamin. The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society.

- ↑ Goldstein, Bernard; Oldham, Jack. Children and Work: A Study of Socialization.

- ↑ "About UNU". ungm.org. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ "United Nations University (UNU)—The United Nations University: Research and Policy Support for Environmental Risk Reduction". link.springer.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ "Head Start in an Era of Standards and Accountability" (PDF). acf.hhs.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ "Economic rationalism, 20 years on". evatt.org.au. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ Smith, Harlan M. Understanding Economics.

- ↑ Glosserman, Brad. Peak Japan: The End of Great Ambitions.

- ↑ "Arms Across the Sea Hardcover – July 1, 1978". amazon.com. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ "Must We Bus? Segregated Schools and National Policy.". eric.ed.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ Dickson, Bruce; Harding, Harry. "Economic Relations in the Asian-Pacific Region". he Journal of Energy and Development.

- ↑ Choice: Publication of the Association of College and Research Libraries, a Division of the American Library Association, Volume 22, Issues 1-6.

- ↑ "The Peterson Institute for International Economics". crunchbase.com. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ Maisel, Louis Sandy. "The Politics of Congressional Elections. by Gary C. Jacobson; From Obscurity to Oblivion: Running in the Congressional Primary".

- ↑ Garvin, Alexander. The Heart of the City: Creating Vibrant Downtowns for a New Century.

- ↑ "Talent Management an Effective Key to Manage Knowledgeable Workers to Fabricate Safer Steel Structure" (PDF). ijssst.info. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ "Unequal Partners: The United States and Mexico". reviews.history.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ Managing Capital Resources for Central City Revitalization (Fritz W. Wagner, Timothy E. Joder, Anthony J. Mumphrey, Jr. ed.).

- ↑ "Tax Reform Act of 1986". britannica.com. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Rural Development Perspectives: RDP.

- ↑ Robel, Lauren K. "Fractured Procedure: The Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990". repository.law.indiana.edu. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ Peru's Path to Recovery: A Plan for Economic Stabilization and Growth (Carlos E. Paredes, Jeffrey D. Sachs ed.).

- ↑ "brook.edu". snoop.com. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ Nelson, Greg. "The Rebirth of Urban Democracy" (PDF). ens.lacity.org. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ "brookings.edu". snoop.com. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ Rich, Andrew (Spring 2006). "War of Ideas: Why Mainstream and Liberal Foundations and the Think Tanks they Support are Losing in the War of Ideas in American Politics" (PDF). Stanford Social Innovation Review. Stanford University.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Jerry Martin. Reawakening: The New, Broader Middle East.

- ↑ "Bush and Kerry: Questions About Governing Styles". ciaonet.org. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ Protecting the American Homeland: One Year On. Brookings Institution Press.

- ↑ Epstein, Jennifer (2012-08-01). "Obama: Romney 'asking you to pay more so that people like him can get a tax cut'". Politico. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ "Tax Policy Center in Spotlight for Its Romney Study" by Annie Lowrey, New York Times, October 24, 2012

- ↑ "Whois Record for TaxPolicyCenter.org". whois.domaintools.com/. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ "Strobe Talbott to be first distinguished visitor at Buffett Institute". Northwestern University. 2017-10-13. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "ABOUT THE CENTER FOR MIDDLE EAST POLICY". brookings.edu. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Brookings Institution Launches Metropolitan Policy Program". brookings.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ "About the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy". Brookings.edu. Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Brookings-Tsinghua Center". Brookings.edu. Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "ABOUT GLOBAL ECONOMY AND DEVELOPMENT". brookings.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ "ABOUT THE BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER". brookings.edu. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ "2008 Global Go To Think Tanks Index Report". repository.upenn.edu. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ "Center on Global Interests". idealist.org. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ "2013 RANKINGS" (PDF). carnegieendowment.org. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ Datta, Kanika (2013-04-26). "Tea with BS: Strobe Talbott". Business Standard India. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "Brookings India". Brookings India. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "2014 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report". repository.upenn.edu. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ "John R. Allen named next Brookings Institution president". Brookings Institution. October 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2017" (PDF). Brookings.edu. Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "The 50 Most Influential Think Tanks in the United States". thebestschools.org. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ↑ "Top 25% Think Tanks, as of December 2019". ideas.repec.org. Retrieved 16 January 2020.