Timeline of WikiLeaks

This is a timeline of WikiLeaks, an international non-profit organization that publishes news leaks.[1]

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1990s | Julian Assange starts hacking systems and is punished with the first cybercrime charges. By the end of the decade, Assange registers leaks.org.

|

| 2000s | wikiLeaks.org website launches in the mid-decade. Collaboration with The Guardian begins. WikiLeaks starts being recognized with awards.

|

| 2010s | Massive information leaks happen at the beginning of the decade,[2] as well as the Bradley Manning case. The organization receives many awards in the 2010s. However, condemnation rises in several countries. In 2016, WikiLeaks intervention disrupts the 2016 United States elections and more precisely the Democrats political campaign. WikiLeaks publishes the biggest ever leak of CIA documents, revealing the agency’s hacking and surveillance techniques.[3] |

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Prelude | United States military analyst Daniel Ellsberg releases the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Pentagon study of the U.S. government decision-making in relation to the Vietnam War, to The New York Times and other newspapers. This study would be Julian Assange inspiration for WikiLeaks.[4] | |

| 1971 | July 3 | Prelude | Julian Assange is born in the province of Queensland, Australia.[5][6] |

| 1990s | Prelude | Julian Assange and other hackers gain control over MILNET for two years with the use of a back door, gaining full access to the Pentagon Security Coordination Center. The IT rebels are also able to use their computers to interfere with the authorities who are investigating them.[7] | |

| 1991 | Prelude | Assange, now a noted computer hacker, pleads guilty to a host of cybercrime charges, but because of his youth he receives only minimal punishment.[4] | |

| c.1993 | Prelude | Assange cumulates 31 counts of computer hacking and related crimes, eventually pleading guilty and paying a minimal fine.[5] | |

| 1999 | Launch | Assange registers leaks.org.[7]

| |

| 2006 | Launch | Assange starts using leaks.org actively.[5]

| |

| 2006 | December | Launch | Sunshine Press launches the wikiLeaks.org website, as part of an international non-profit organization that obtains and publishes sensitive information.[7][4]

|

| 2006 | December 26 | Release | The first posting on leaks.org is a decision (never verified) by a Somali rebel leader to execute government officials.[5][8]

|

| 2007 | Launch | Assange announces the formal launch of WikiLeaks.[5] | |

| 2007 | Partnership | Assange initiates a relationship with British daily newspaper The Guardian, which reportedly receives regular emails from WikiLeaks “editor-in-chief” Assange, sometimes with a "good story to tell".[5] | |

| 2007 | August 31 | Partnership | WikiLeaks and The Guardian work in tandem for the first time, with WikiLeaks posting the full text off, and the Guardian running a story on, a report by the private investigations firm Kroll about the alleged corruption of former Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi.[5] |

| 2007 | November | Release | WikiLeaks posts the standard operating procedures for the U.S. Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[4] |

| 2007 | December | Release | WikiLeaks posts the United States Army manual for soldiers dealing with prisoners at Camp Delta, a permanent American detainment camp at Guantanamo Bay.[9] |

| 2007 | Team | German activist Daniel Domscheit-Berg begins working with WikiLeaks after meeting Assange at the Chaos Computer Club's annual conference (24C3).[10] | |

| 2008 | March | Release | WikiLeaks publishes internal material from the Church of Scientology. This would lead to the group threatening suit on the grounds of copyright infringement.[4][9] |

| 2008 | April | Recognition | Wikileaks is awarded The Economist's New Media Award at the Index on Censorship Awards.[11] |

| 2008 | September | Release | WikiLeaks posts emails from the Yahoo email account of US politician Sarah Palin.[9] |

| 2008 | November | Release | WikiLeaks posts a list of names and addresses of people it claims belong to British National Party, a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom.[9] |

| 2008 | Recognition | WikiLeaks receives The Economist New Media Award.[12] | |

| 2009 | March 16 | Censorship | The Australian Communications and Media Authority adds WikiLeaks to their proposed list of sites that will be blocked for all Australians if the mandatory internet filtering scheme is implemented as planned.[13][14] The blacklisting would be removed by 29 November 2010.[15] |

| 2009 | April 9 | Censorship | Germany deletes wikileaks.de domain two weeks after the house of the German WikiLeaks domain sponsor, Theodor Reppe, was searched by German authorities.[16]

|

| 2009 | June | Recognition | Wikileaks is awarded the Amnesty International's UK Media Award.[17][18] |

| 2009 | September 14 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes the "Minton report", a study commissioned by Trafigura to determine the toxicity of the waste dumped in Abidjan during the 2006 Ivory Coast toxic waste dump.[8][19][20] |

| 2009 | November | Release | WikiLeaks posts more than half a million pager messages sent within a 24-hour period around the September 11 attacks. Revealing messages include exchanges from "The Pentagon, FBI, FEMA and New York Police Department" officials. WikiLeaks states about the release: "We hope that its entrance into the historical record will lead to a nuanced understanding of how this event led to death, opportunism and war."[21] |

| 2009 | Recognition | WikiLeaks is awarded The Amnesty New Media Award.[12] | |

| 2010 | February | Funding | WikiLeaks announces it has been given the US$200,000 in donations it needs to continue work.[22] |

| 2010 | April 5 | Release | WikiLeaks posts a classified military video showing a Boeing AH-64 Apache firing on and killing two journalists and a number of Iraqi civilians in 2007. The military claims that the helicopter crew believed the targets were armed insurgents, not civilians.[9] |

| 2010 | May | Legal | The first formal charges are filed when low-level U.S. Army intelligence analyst Bradley Manning is arrested in connection with the release of the 2007 helicopter video.[4] |

| 2010 | May 19 | Recognition | The New York Daily News lists WikiLeaks first among websites "that could totally change the news".[23] |

| 2010 | May 26 | Legal | The United States Armed Forces detains Bradley Manning on charges of illegally downloading hundreds of thousands of classified US documents, including the US helicopter gunship attack posted on WikiLeaks, and classified State Department records. Manning is turned in by threat analyst Adrian Lamo, who Manning confided in about leaking the classified records.[9][5] |

| 2010 | July 6 | Legal | The United States Armed Forces announce having charged Bradley Manning with violating army regulations by transferring classified information to a personal computer and adding unauthorized software to a classified computer system and of violating federal laws of governing the handling of classified information.[9] |

| 2010 | July 17 | Support | American independent journalist Jacob Appelbaum speaks on behalf of WikiLeaks at the Hackers on Planet Earth conference in New York City, replacing Assange because of the presence of federal agents at the conference.[24][25] He announces that the WikiLeaks submission system is again operating, after it has been suspended temporarily.[24][26] |

| 2010 | July 25 | Release | WikiLeaks posts more than 90,000 classified documents relating to the War in Afghanistan. This would be called the biggest leak since the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. The documents are divided into more than 100 categories and touch on everything from the hunt for Osama bin Laden to Afghan civilian deaths resulting from US military actions."[9] |

| 2010 | July | Support | Veterans for Peace president Mike Ferner writes on the group's website "neither Wikileaks nor the soldier or soldiers who divulged the documents should be prosecuted for revealing this information. We should give them a medal."[27] |

| 2010 | August | Team | WikiLeaks decides to move their headquarters to Uppsala and begins to mainly be hosted by the Swedish internet service provider Bahnhof, where there are now a couple WikiLeaks servers in the Pionen facility.[7] |

| 2010 | August 18 | Censorship | The Thai Government blocks access to WikiLeaks website in its country.[28] |

| 2010 | August | Support | Documentary filmmaker John Pilger writes an editorial in the Australian publication Green Left titled "Wikileaks must be defended." In it, Pilger says WikiLeaks represents the interests of "public accountability" and a new form of journalism at odds with "the dominant section ... devoted merely to taking down what cynical and malign power tells it."[29] |

| 2010 | August | Security | Some portion of Wikileaks' servers are moved to a data center in Pionen, a former civil defence center located 30 meters below ground inside a Cold-War-era nuclear bunker carved out of a large rock hill in downtown Stockholm.[30] |

| 2010 | October 22 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes nearly 400,000 classified military documents from the Iraq War, providing new figures of deceased Iraqi civilians, as well as the role that Iran has played in supporting Iraqi militants and many accounts of abuse by Iraq's army and police.[9] "So, WikiLeaks published the Iraq War Logs on October 22nd of 2010. In so doing, it became the biggest leak in the military history of America up to that point, far surpassing the Afghan War Diary of July 25th from that same year."[7] |

| 2010 | October 23 | Recognition | WikiLeaks and Assange are awarded the 2010 Sam Adams Associates for Integrity in Intelligence award for releasing secret U.S. military reports on the Iraq and Afghan wars.[31] |

| 2010 | November 28 | Release | WikiLeaks begins publishing approximately 250,000 diplomatic cables from the United States Department of State dating back to 1966. The site says the documents will be released "in stages over the next few months."[9][32] |

| 2010 | November 28 | Reaction | wikileaks.org suffers an attack designed to make it unavailable to users. A Twitter user called Jester claims responsibility for the attack.[9]

|

| 2010 | November 29 | Support | Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez states his support for WikiLeaks following the release of US diplomatic cables in November 2010 showing the United States attempts to rally support from regional governments to isolate Venezuela.[33] |

| 2010 | November | Release | WikiLeaks releases selections from a list of some 250,000 classified diplomatic cables between the United States Department of State and its embassies and consulates around the world. These secret documents contain U.S. efforts to politically and economically isolate Iran, primarily in response to fears of Iran’s development of nuclear weapons.[4] |

| 2010 | November | Public opinion | According to a telephone survey of 1,004 German residents age 18 and older, a majority of 53% disapprove of WikiLeaks, while 43% are generally in favour of the platform. Asked about the specific release of US diplomatic cables, almost two Thirds (65%) believe that these documents should not be published, compared to 31% that agree that they are being released to the public.[34] |

| 2010 | November | Team | The WikiLeaks-endorsed news and activism site WikiLeaks Central is initiated and administrated by editor Heather Marsh.[35][36] |

| 2010 | November 30 | Censorship | China blocks Internet access to WikiLeaks' release of more than 250,000 leaked cables from the United States Department of State, with its Foreign Ministry saying that it does not wish to see any disturbance in China–United States relations.[37] |

| 2010 | December 1 | Reaction | Amazon.com removes WikiLeaks from its servers after political pressure.[38][39][40] |

| 2010 | December 2 | Reaction | Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard makes a statement that she 'absolutely condemns' WikiLeaks' actions and that the release of information on the site is 'grossly irresponsible' and 'illegal.'[41] |

| 2010 | December 2 | Reaction | EveryDNS.net drops wikiLeaks.org as a client, citing the danger that the cyber attacks aimed at that site poses to the service's 500,000 other clients.[42]

|

| 2010 | December 3 | Reaction | The Obama administration bans hundreds of thousands of federal employees from calling up the WikiLeaks site on government computers because the leaked material is still formally regarded as classified.[43] The White House Office of Management and Budget sends a memorandum forbidding all unauthorized federal government employees and contractors from accessing classified documents publicly available on WikiLeaks and other websites.[44] |

| 2010 | December 9 | Support | United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Opinion and Expression Frank LaRue states he agrees with the idea that Julian Assange is a "martyr for free speech." LaRue goes on to say Assange or other WikiLeaks staff should not face legal accountability for any information they disseminated, noting that, "if there is a responsibility by leaking information it is of, exclusively of the person that made the leak and not of the media that publish it. And this is the way that transparency works and that corruption has been confronted in many cases."[45] High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, subsequently voices concern at the revelation that private companies are being pressured by states to sever their relationships with WikiLeaks.[46] |

| 2010 | December 15 | Reaction | Philipino President Benigno Aquino III condemns WikiLeaks and leaks documents related to the country, saying that it can lead to massive cases of miscommunication.[47] |

| 2010 | December 21 | Reaction | Media reports that Apple Inc. has removed an application from its App Store, which provided access to the embassy cable leaks.[48] |

| 2010 | December | Support | Noam Chomsky offers his support to protesters across Australia planning to take to the streets in defence of WikiLeaks.[49] In an interview for Democracy Now!, Chomsky criticizes the government response, saying, "perhaps the most dramatic revelation ... is the bitter hatred of democracy that is revealed both by the U.S. Government – Hillary Clinton, others – and also by the diplomatic service."[50] |

| 2010 | December | Spin-off | Daniel Domscheit-Berg announces the intention to start a site named "OpenLeaks".[51][52] |

| 2010 | December | Reaction | wikileaks.org faces a number of setbacks, being forced to go off-line once again when the site’s domain name provider terminates its account in the wake of a series of distributed denial-of-service attacks. However, as with previous service interruptions, WikiLeaks remains available on mirror sites or by directly linking to its IP address.[4]

|

| 2010 | December | Legal | The British police arrests Assange on an outstanding Swedish warrant for alleged sex crimes.[4] |

| 2010 | December | Reaction | PayPal, Visa, and Mastercard suspend online payment processing for donations to WikiLeaks.[4] |

| 2010 | December | Recognition | Assange is named "Person of the Year" by Time Magazine.[6] |

| 2010 | December | Recognition | The office of the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev issues a statement calling on non-governmental organisations to consider "nominating Julian Assange as a Nobel Prize laureate." The announcement follows commentary by Russian ambassador to NATO Dmitry Rogozin who stated that Julian Assange's earlier arrest on Swedish charges demonstrated that there was "no media freedom" in the west.[53] |

| 2010 | December | Public opinion | A research poll shows that the majority of Australians are against the official government position on WikiLeaks. The findings were done on 1,000 individuals, showing 59% support WikiLeaks' action in making the cables public and 25% oppose it.[54] |

| 2010 | December | Public opinion | According to a telephone survey of 1,029 US residents age 18 and older, conducted by the Marist Institute for Public Opinion, 70% of American respondents – particularly Republicans and older people – think the leaks are doing more harm than good by allowing enemies of the United States government to see confidential and secret information about U.S. foreign policy. Approximately 22% – especially young liberals – think the leaks are doing more good than harm by making the U.S. government more transparent and accountable. A majority of 59% also want to see the people behind WikiLeaks prosecuted, while 31% said the publication of secrets is protected under the First Amendment guarantee of a free press.[55] |

| 2010 | December | Wikileaks website, wikileaks.org, redirects web traffic to a 3rd party mirror site, mirror.wikileaks.info., a new website which is hosted in Russian Webalta's 92.241.160.0/19 IP address space, a network which The Spamhaus Project believes caters primarily to, or is under the control of, Russian cybercriminals.[56]

| |

| 2010 | Recognition | WikiLeaks is awarded The Sam Adams Award for Integrity.[12] | |

| 2011 | January | Reaction | Libyan politician Muammar Gaddafi blames WikiLeaks for the Tunisian revolution stating "[Do not be fooled by] WikiLeaks which publishes information written by lying ambassadors in order to create chaos."[57] |

| 2011 | January | Spin-off | RuLeaks launches as a Russian version of WikiLeaks. The website begins translating and mirroring publications by the original WikiLeaks, but it would quickly switch to original content.[58] |

| 2011 | April | Release | WikiLeaks begins publishing more secret files from the military facilities at Guantanamo Bay, containing detailed information about the majority of prisoners detained at the detention camp from 2002 to 2008, including photographs, health records, and assessments of the potential threat posed by each prisoner. The files also indicates that dozens of detainees have passed through radicalized British mosques prior to their departure for Afghanistan and, ultimately, their capture by United States forces.[4] |

| 2011 | April 25 | Release | Guantanamo Bay files leak. WikiLeaks obtains nearly 800 classified US military documents revealing details about the alleged terrorist activities of Al Qaeda operatives captured and housed in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[59][60][8] |

| 2011 | June | Recognition | Assange is awarded the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism.[61] |

| 2011 | July 14 | Reaction | WikiLeaks and DataCell ehf. of Iceland file a complaint against the international card companies, VISA Europe and MasterCard Europe, for infringement of the antitrust rules of the EU, in response to their withdrawal of financial services to the organization. In a joint press release, the organizations state: "The closure by VISA Europe and MasterCard of Datcell's access to the payment card networks in order to stop donations to WikiLeaks violates the competition rules of the European Community."[62] DataCell files a complaint[63] with the European Commission on 14 July 2011. |

| 2011 | August | Spin-off | Leakymails launches in Argentina as a project designed to obtain and publish relevant documents exposing corruption of the political class and the powerful in the country.[64][65][66][67] |

| 2011 | September 2 | Release | Assange releases its archive containing more than 250,000 unredacted US diplomatic cables.[9] |

| 2011 | October 24 | WikiLeaks announces a temporary halt in publication in order to focus its efforts on fund-raising. Assange states that a financial blockade by Bank of America, VISA, MasterCard, PayPal and Western Union has cut off 95% of WikiLeaks' revenue.[9][4] | |

| 2011 | December 1 | Release | Wikileaks releases more than 287 files exposing 160 intelligence contracting companies in 25 countries that "develop technologies to allow the tracking and monitoring of individuals by their mobile phones, email accounts and Internet browsing histories".[8][68][69] |

| 2011 | December | Spin-off | WikiLeaks launches Friends of WikiLeaks, a social network for supporters and founders of the website.[70] |

| 2011 | Recognition | Icelandic investigative journalist and WikiLeaks spokesperson Kristinn Hrafnsson is awarded The National Union of Journalists Journalist of the Year.[12] | |

| 2011 | Recognition | WikiLeaks is awarded The Sydney Peace Foundation Gold Medal, the Blanquerna Award for Best Communicator, the Walkley Award for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism, the Voltaire Award for Free Speech, the International Piero Passetti Journalism Prize of the National Union of Italian Journalists, and the Jose Couso Press Freedom Award.[12] | |

| 2012 | January | Spin-off | Honest Appalachia initiates as a website based in the United States intended to appeal to potential "whistleblowers" in West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina, and serve as a replicable model for similar projects elsewhere.[71][72] |

| 2012 | February 23 | Legal | Bradley Manning is formally charged with aiding the enemy, wrongfully causing intelligence to be published on the Internet, transmitting national defense information and theft of public property or records.[9] |

| 2012 | February | Release | WikiLeaks publishes secret emails from American geopolitical intelligence platform Stratfor that shows US authorities have drawn up secret charges against Assange.[73][9] |

| 2012 | March 8 | Team | Heather Marsh resigns from WikiLeaks.[74] |

| 2012 | July 5 | Release | WikiLeaks begins publishing more than 2.4 million emails from Syrian politicians, government ministries and companies.[9] |

| 2012 | June | Legal | Assange applies for asylum in Ecuador and seeks refuge in the Embassy of Ecuador, London, after his extradition appeal was denied and with a Swedish arrest warrant pending.[4] "According to a New York Times article, Assange came to the Ecuadorean Embassy in London in June 2012, seeking to avoid extradition to Sweden. "[6] |

| 2012 | Recognition | WikiLeaks is awarded The Privacy International Hero of Privacy.[12] | |

| 2013 | February 4 | Recognition | Assange is awarded in New York with the Yoko Ono Lennon Courage Award for the Arts.[75] |

| 2013 | February 28 | Legal | Bradley Manning pleads guilty to some of the 22 charges against him, except the most serious charge of aiding the enemy, which carries a life sentence.[9] |

| 2013 | April | Recognition | WikiLeaks is awarded the Global Exchange Human Rights People’s Choice Award.[76] |

| 2013 | July | Political campaign | Assange launches the WikiLeaks Party in Australia and announces his candidacy for a seat in the Australian Senate.[4] |

| 2013 | August | Legal | Though being acquitted of aiding the enemy Bradley Manning is sentenced by military judge to 35 years in prison.[4][9] |

| 2013 | September 9 | Spin-off | A number of major Dutch media outlets support the launch of Publeaks, which provides a secure website for people to leak documents to the media using the GlobaLeaks whistleblowing software.[77][78] |

| 2013 | September 20 | Recognition | Assange is awarded the Brazillian Press Association Human Rights Award.[79] |

| 2014 | April | Release | Sony Pictures becomes the target of a massive data breach, and a group calling itself the Guardians of Peace soon begin releasing sensitive company information in small batches. The hack is eventually attributed to North Korea. The following April, WikiLeaks published more than 200,000 of the stolen documents in a searchable database, a move that was immediately criticized by Sony."[4] |

| 2014 | June | Recognition | Assange is awarded the Kazakstan Union of Journalists Top Prize.[80] |

| 2015 | January 26 | WikiLeaks' lawyers address Google and the United States Department of Justice concerning a serious violation of the privacy and journalistic rights of WikiLeaks' staff, after investigations editor Sarah Harrison, Section Editor Joseph Farrell and senior journalist and spokesperson Kristinn Hrafnsson received notice that Google has handed over all their emails and metadata to the United States government on the back of alleged 'conspiracy' and 'espionage' warrants.[81] | |

| 2015 | June 19 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes 500,000 cables and Foreign Ministry documents from the Saudi Government.[82][83][8] |

| 2015 | October | Recognition | WikiLeaks section editor Sarah Harrison is awarded the Willy Brandt Award for Political Courage.[84] |

| 2015 | November 16 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes the "Final Texts" of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal.[85][86][87][88][8] |

| 2016 | March | Release | WikiLeaks unveils a searchable archive containing 30,000 e-mail messages and attachments retrieved from a private server maintained by Hillary Clinton during her tenure as United States Secretary of State (2009–13). The collection is made public by the State Department through the Freedom of Information Act.[4] |

| 2016 | May 25 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes documents from the Trade in Services Agreement trade deal.[8] |

| 2016 | July 20 | Censorship | The Turkish government blocks access to Wikileaks after it releases nearly 300,000 emails involving the ruling Justice and Development Party. The email releases are in response to the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt.[89] |

| 2016 | July 22 | Release | An amount of nearly 20,000 emails from Democratic National Committee staffers is released by WikiLeaks. The emails appear to show the committee favoring Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders during the United States presidential primary.[9] |

| 2016 | July | Release | WikiLeaks publishes more than 60,000 Democratic National Committee (DNC) e-mail messages and documents, days before the Democratic Party officially nominates Clinton as its candidate in the US Presidential Election 2016.[4] |

| 2016 | October 7 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes the Podesta emails, a collection of 58,660 emails from Hillary Clinton campaign Chairman John Podesta.[90][91][8] |

| 2016 | October 11 | Authenticity | Writer Glenn Greenwald asserts that WikiLeaks has a "perfect, long-standing record of only publishing authentic documents."[92] |

| 2016 | October 13 | Authenticity | Columnist Eric Zorn writes "So far, it's possible, even likely, that every stolen email WikiLeaks has posted has been authentic." but cautions against assuming that future releases would be equally authentic.[93] |

| 2016 | October 16 | Wikileaks tweets a series of three unusually cryptic, confusing messages, each containing a 64-character code. The posts are followed by rumors questioning whether Assange is dead or alive, with some people believing Assange was killed or is currently in grave danger, and that a dead man’s switch was activated.[94][95] | |

| 2016 | November 25 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes the Yemen Files, a collection of more than 500 documents from the United States Embassy in Sana’a, Yemen, which offer documentary evidence of the arming, training and funding of Yemeni forces by the United States in the years building up to the Yemeni civil war.[96][97][8] |

| 2016 | December 1 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes the German BND-NSA Inquiry Exhibits, an amount of 90 gygabites of information relating to the BND-NSA Inquiry.[98][99][8] |

| 2017 | January 3 | Assange announces in interview that Russia did not give WikiLeaks hacked emails.[9] | |

| 2017 | January 12 | WikiLeaks tweets that Assange will agree to be extradited to the United States if Obama grants clemency to Bradley Manning (now Chelsea Manning).[9] | |

| 2017 | January 17 | Legal | United States President Barack Obama commutes the sentence of Chelsea Manning, setting the stage for her to be released on May 17.[100] |

| 2017 | January | The WikiLeaks Task Force, a Twitter account associated with WikiLeaks,[101] proposes the creation of a database to track verified Twitter users, including sensitive personal information on individuals' homes, families and finances.[102][101][103] The Chicago Tribune would describe the proposal as facing a "sharp and swift backlash as technologists, journalists and security researchers slammed the idea as a 'sinister' and dangerous abuse of power and privacy."[102] Twitter furthermore bans the use of Twitter data for "surveillance purposes," stating "Posting another person's private and confidential information is a violation of the Twitter rules."[101] | |

| 2017 | February 16 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes CIA espionage orders for the 2012 French presidential election.[104][8] Assange claims he has damaging information on the leading French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron having a homosexual affair.[105] |

| 2017 | March 7 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes thousands of internal CIA documents (known as Vault 7), including alleged discussions of a covert hacking program and the development of spy software targeting cellphones, smart TVs and computer systems in cars. Assange states that the website published the documents as a warning about the risk of the proliferation of "cyber weapons". However, the documents are not independently authenticated.[106] |

| 2017 | April | Reaction | In a speech addressing the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CIA Director Mike Pompeo refers to WikiLeaks as "a non-state hostile intelligence service" and described founder Julian Assange as a narcissist, fraud, and coward.[107] |

| 2017 | May 3 | Reaction | FBI Director James Comey refers to WikiLeaks as "intelligence porn" during a Senate hearing, and declares that the site's disclosures are intended to damage the United States rather than educate the public.[9] |

| 2017 | May 17 | Legal | Chelsea Manning is released from prison.[108] |

| 2017 | October | CNN reports that in 2016 a Cambridge Analytica executive approached WikiLeaks requesting access to emails from Hillary Clinton. Assange confirms the exchange in a tweet.[109] | |

| 2018 | September 28 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes a secret document concerning a dispute over a £3.6 billion Middle Eastern arms deal.[110][111][8] |

| 2018 | October 11 | Release | WikiLeaks publishes a "Highly Confidential" internal document from the cloud computing provider Amazon which lists the addresses of over 100 data centers in nine countries including China, Singapore and Japan.[112][113][8] |

| 2019 | January | WikiLeaks sends a 5,000-word email to journalists listing 140 things they should not say about Assange, from asserting that he has been an agent of any intelligence service to that he has ever bleached his hair.[114] | |

| 2019 | April | Legal | Assange asylum is rescinded, and he is indicted in the United States for violating the Espionage Act.[6] |

| 2019 | April | Recognition | Assange is awarded the Galizia Prize for Journalists, Whistleblowers & Defenders of the Right to Information.[115][116][117] |

Numerical and visual data

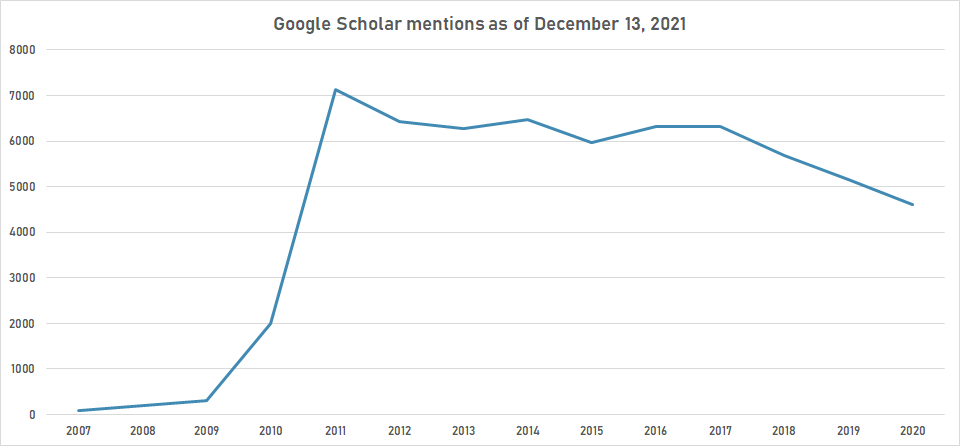

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 13, 2021.

| Year | WikiLeaks |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 89 |

| 2008 | 197 |

| 2009 | 299 |

| 2010 | 2,000 |

| 2011 | 7,130 |

| 2012 | 6,420 |

| 2013 | 6,270 |

| 2014 | 6,480 |

| 2015 | 5,970 |

| 2016 | 6,320 |

| 2017 | 6,330 |

| 2018 | 5,680 |

| 2019 | 5,150 |

| 2020 | 4,610 |

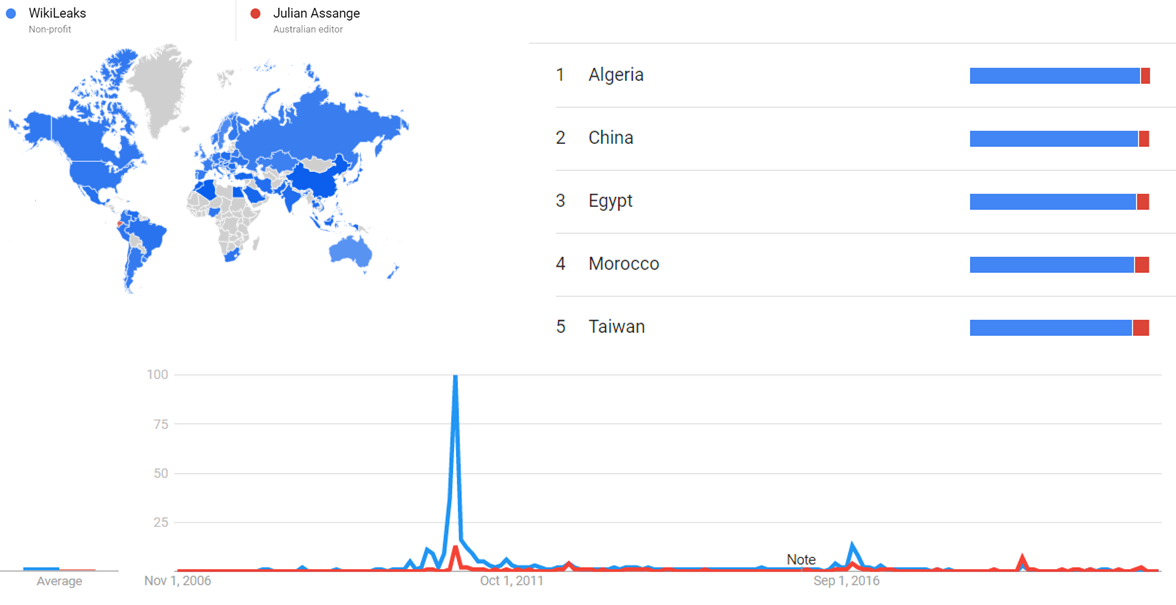

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for WikiLeaks (Non-profit) and Julian Assange (Australian editor), from October 2006 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[118]

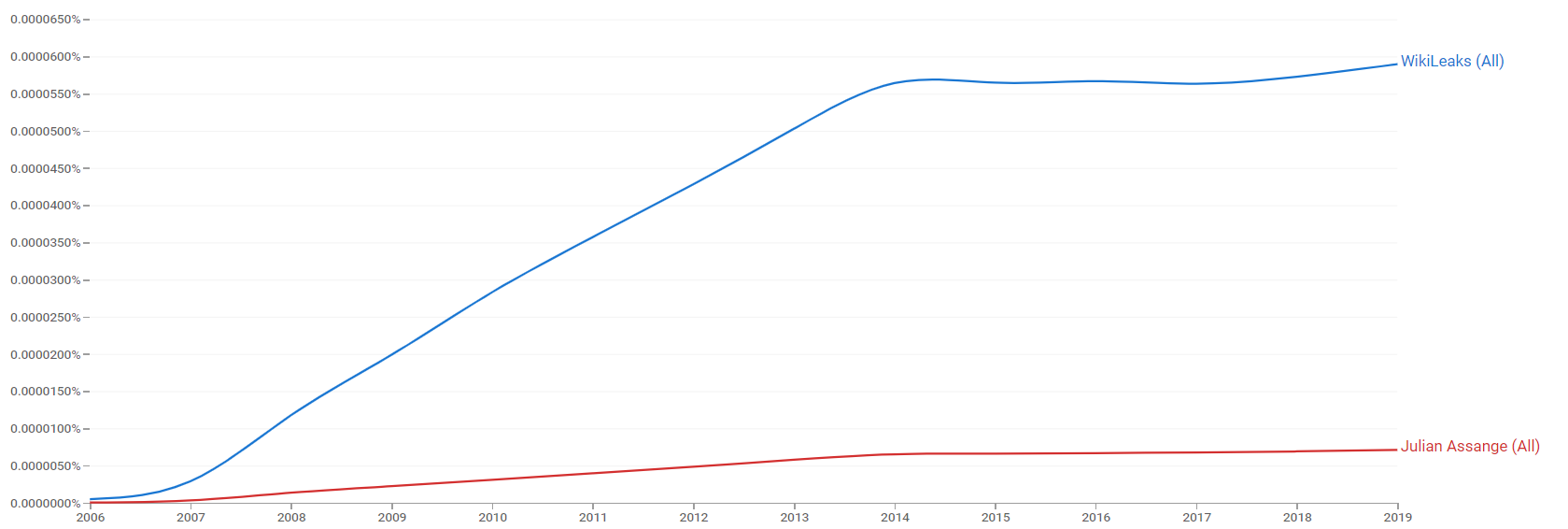

Google Ngram Viewer

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for WikiLeaks and Julian Assange, from 2006 to 2019.[119]

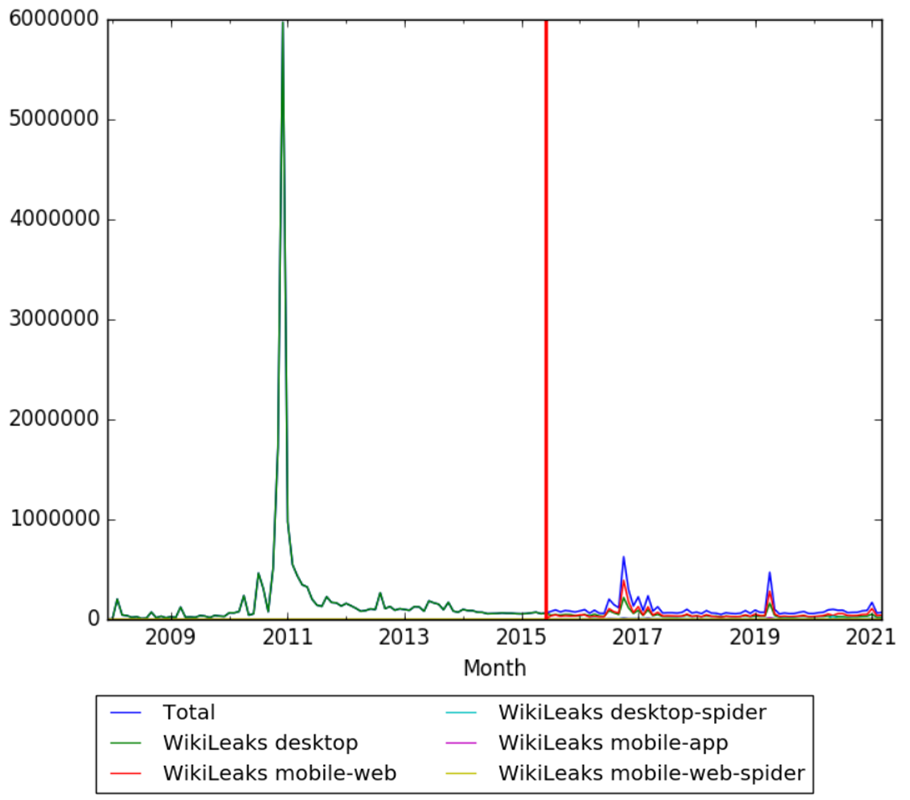

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article WikiLeaks, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to March 2021.[120]

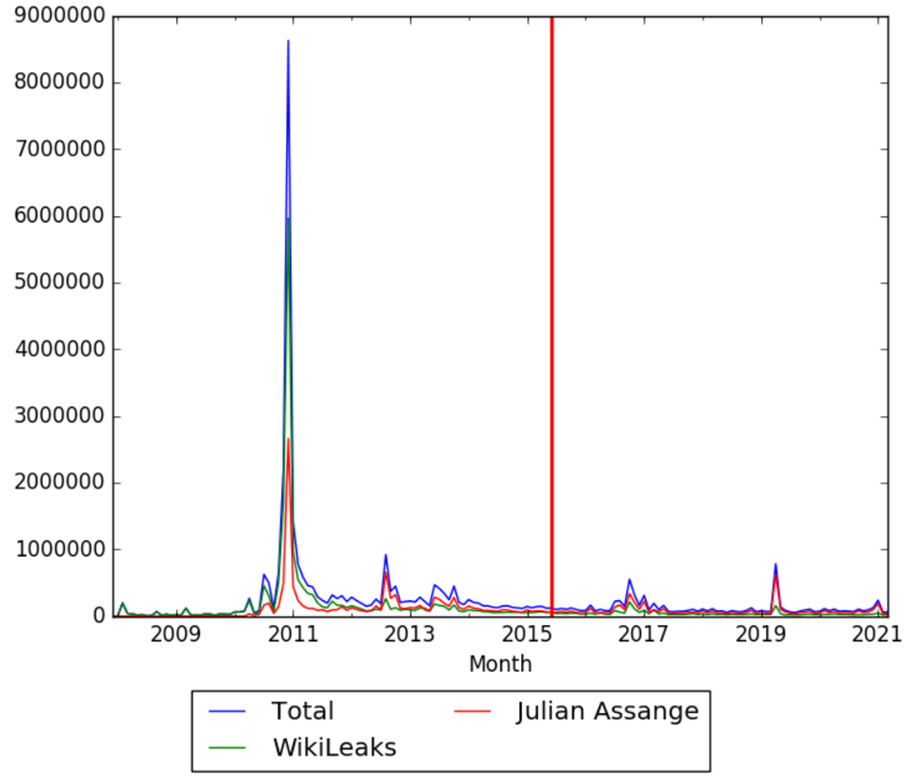

The comparative chart below shows pageviews on desktop of the English Wikipedia articles WikiLeaks and Julian Assange from December 2007 to March 2021.[121]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Karhula, Päivikki (5 October 2012). "What is the effect of WikiLeaks for Freedom of Information?". International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "US intelligence versus Julian Assange - a brief history". euronews.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "Radical who refused to compromise". mondediplo.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 "WikiLeaks". britannica.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "WikiLeaks: a brief history". ccnmtl.columbia.edu. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Julian Assange Biography". biography.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "A History of WikiLeaks". medium.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 "How WikiLeaks works". defend.wikileaks.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 "WikiLeaks Fast Facts". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Hosenball, Mark (2010-12-15). "Julian Assange vs. the world". National Post.

- ↑ "Winners of Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Announced". Index on Censorship. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Awards". medium.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ Moses, Asher (16 March 2009). "Banned hyperlinks could cost you $11,000 a day". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Australia secretly censors Wikileaks press release and Danish Internet censorship list, 16 Mar 2009". Mirror.wikileaks.info. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Taylor, Josh (29 November 2010). "Wikileaks removed from ACMA blacklist". ZDNet Australia. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Germany deletes WikiLeaks.de domain after raid". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "The Cry of Blood. Report on Extra-Judicial Killings and Disappearances". Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Amnesty announces Media Awards 2009 winners" (Press release). Amnesty International UK. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Minton report: Trafigura toxic dumping along the Ivory Coast broke EU regulations, 14 Sep 2006". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ News Across Media: Production, Distribution and Consumption (Jakob Linaa Jensen, Mette Mortensen, Jacob Ørmen ed.).

- ↑ "Six big leaks from Julian Assange's WikiLeaks over the years". usatoday.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Nickson, Chris. "WikiLeaks fixes its money leak". techradar.com. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ↑ Reso, Paulina (20 May 2010). "5 pioneering Web sites that could totally change the news". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Singel, Ryan (19 July 2010). "Wikileaks Reopens for Leakers". Wired. New York. Archived from the original on 2014-02-09. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ McCullagh, Declan (16 July 2010). "Feds look for WikiLeaks founder at NYC hacker event | Security". CNET News. Archived from the original on 2011-08-27. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Jacob Appelbaum WikiLeaks Next HOPE Keynote Transcript". "Hackers on Planet Earth" conference. 17 July 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks revelations will spark massive resistance to Afghanistan War". Veterans For Peace. 27 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Thailand Blocks Access To WikiLeaks Website". forum.thaivisa.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "John Pilger: Wikileaks must be defended | Green Left Weekly". Greenleft.org.au. 29 August 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "Wikileaks Servers Move To Underground Nuclear Bunker". forbes.com. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks and Assange Honored". consortiumnews.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "State Department Tried To Dissuade WikiLeaks From Posting U.S. Documents". npr.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ↑ Cancel, Daniel (29 November 2010). "Chavez Praises Wikileaks for `Bravery' While Calling on Clinton to Resign". Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "ARD Deutschland Trend" (PDF). Infratest dimap. December 2010. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Dorling, Philip. "Building on WikiLeaks". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Supporters". Wikileaks. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "China Blocks Access to WikiLeaks". pcworld.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks website pulled by Amazon after US political pressure". theguardian.com. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ O’CONNOR, ANAHAD. "Amazon Removes WikiLeaks From Servers". nytimes.com. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks: Amazon.com Kicked Us Off Servers". cbsnews.com. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ Paul Ramadge, ed. (2 December 2010). "Gillard condemns WikiLeaks". The Age. Australia: Fairfax Media. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "How Has WikiLeaks Managed to Keep Its Web Site Up and Running?". scientificamerican.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "US blocks access to WikiLeaks for federal workers". theguardian.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ de Sola, David (4 December 2010). "U.S. agencies warn unauthorized employees not to look at WikiLeaks". CNN. Archived from the original on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Hall, Eleanor (9 December 2010). "UN rapporteur says Assange shouldn't be prosecuted". abc.net.au. ABC Online. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ Nebehay, Stephanie (9 December 2010). "UN rights boss concerned at targeting of WikiLeaks". reutres. Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ Esplanada, Jerry E. (15 December 2010). "Foreign Office slams WikiLeaks". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Mitchell, Stewart (21 December 2010). "Apple pulls WikiLeaks app". PC Pro. London. Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Noam Chomsky backs Wikileaks protests in Australia". Green Left Weekly. 10 December 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks Cables Reveal "Profound Hatred for Democracy on the Part of Our Political Leadership"". Noam Chomsky website. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "About OpenLeaks". OpenLeaks. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Piven, Ben (17 December 2010). "Copycat WikiLeaks sites make waves". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ Harding, Luke (9 December 2010). "Julian Assange should be awarded Nobel peace prize, suggests Russia". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ Lester, Tim (6 January 2011). "Strong support for WikiLeaks among Australians". The Age. Australia. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "McClatchy-Marist Poll National Survey December 2010" (PDF). Marist Institute for Public Opinion. 10 December 2010. pp. 21–24. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "Wikileaks Mirror Malware Warning". spamhaus.org. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "Libya's Gaddaffi pained by Tunisian revolt, blames WikiLeaks". Monsters and Critics. 16 January 2011. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Russia's Own WikiLeaks Takes Off". themoscowtimes.com. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks Reveals Secret Files on All Guantánamo Prisoners". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Timeline of Guantanamo Bay Military Commissions". peacefultomorrows.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Julian Assange wins Martha Gellhorn journalism prize". theguardian.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Press release, 14 July 2011". Wikileaks.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Complaint to the EU commission" (PDF). Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "Leakymails: "Nos encontramos en posibilidad de arruinar de un solo golpe a la clase política entera"". ambito.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Argentina: Judge orders all ISPs to block corruption reporting website". 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Argentina: Judge orders all ISPs to block the sites LeakyMails.com and Leakymails.blogspot.com". 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Argentine ISPs Use Bazooka to Kill Fly". 19 August 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "The Spy Files". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks' latest "Spy Files" document release exposes secrets of global surveillance". knightcenter.utexas.edu. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Wikileaks launches Social Network". Netzwelt.de. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Honest Appalachia". Archived from the original on 2 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Honest Appalachia launches whistleblower site". whistleblowersblog.org. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ "Ecuador shows up Australian government on Assange asylum". greenleft.org.au. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ↑ Marsh, Heather. "To Whom It May Concern". WL Central. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 February 2016 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "WikiLeaks Founder Assange Awarded Yoko Ono Lennon Courage Award for the Arts". democracynow.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "And the People's Choice Award Winner is…". globalexchange.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Handling ethical problems in counterterrorism An inventory of methods to support ethical decisionmaking" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Vanaf vandaag: anoniem lekken naar media via doorgeefluik Publeaks". De Volkskrant. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Brazilian Press Association: International Human Rights Award". edwardsnowden.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Kazakh Journalists' Union Honors WikiLeaks Founder". rferl.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Google hands data to US Government in WikiLeaks espionage case". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks publishes the Saudi Cables". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks to release 500,000 Saudi diplomatic cables, including paper on 'Bin Laden inheritance'". scmp.com. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Sarah Harrison acceptance speech for the Willy Brandt Prize for political courage". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "Trade in Services Agreement". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks releases documents related to controversial US trade pact". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Trans-Pacific-Partnership - Final Texts". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ Journalism, Power and Investigation: Global and Activist Perspectives (Stuart Price ed.).

- ↑ "Turkey blocks access to WikiLeaks after ruling party email dump". Reuters. July 20, 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "The Podesta Emails". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "WIKILEAKS RELEASES PODESTA EMAILS SHORTLY AFTER "ACCESS HOLLYWOOD" TAPE RELEASED". themoscowproject.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ Greenwald, Glenn. "In the Democratic Echo Chamber, Inconvenient Truths Are Recast as Putin Plots". The Intercept.

- ↑ Eric Zorn, The inherent peril in trusting whatever WikiLeaks dumps on us, Chicago Tribune (13 October 2016).

- ↑ "These Cryptic Wikileaks Tweets Don't Mean Julian Assange Is Dead". gizmodo.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "Is Julian Assange Dead Or Alive?". inquisitr.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "Yemen Files". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks Drops Yemen Files, Unmasks Washington's Bloody Role". telesurenglish.net. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "German BND-NSA Inquiry Exhibits". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Wikileaks releases 2,420 documents from German government NSA inquiry". dw.com. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Obama commutes sentence of Chelsea Manning". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 Jessica Guynn (6 January 2017). "WikiLeaks threatens to publish Twitter users' personal info". USA Today.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Fung, Brian. "WikiLeaks proposes tracking verified Twitter users' homes, families and finances". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ Mali, Meghashyam (6 January 2017). "WikiLeaks floats creating database of Twitter users' personal data". The Hill. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ↑ "CIA espionage orders for the 2012 French presidential election". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ Fearnow, Benjamin. "Emmanuel Macron Emails: Wikileaks Releases French President's Campaign Messages". ibtimes.com. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks claims to reveal how CIA hacks TVs and phones all over the world". money.cnn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "Director Pompeo Delivers Remarks at CSIS – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ↑ "Out of prison, Chelsea Manning looks forward to exploring life as a woman". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "Trump campaign analytics company contacted WikiLeaks about Clinton emails". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ "Dealmaker: Al Yousef". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "New WikiLeaks Release Exposes Corruption in UAE Arms Deal Fueling War on Yemen". mintpressnews.com. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Amazon Atlas". wikileaks.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks publishes 'highly confidential' Amazon document with its data centers; offices in China, Japan, Singapore, none in India". mynation.com. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ "Julian Assange arrested after almost 7 years in embassy". euronews.com. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ↑ "Julian Assange Wins 2019 EU Journalism Award". telesurenglish.net. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Julian Assange wins EU journalism award". smh.com.au. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ "Julian Assange awarded 2019 Galizia Prize". defend.wikileaks.org. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks and Julian Assange". Google Trends. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks and Julian Assange". books.google.com. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks and Julian Assange". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.