Timeline of existential risk

This is a timeline of existential risk. According to the Future of Life Institute, "an existential risk is any risk that has the potential to eliminate all of humanity or, at the very least, kill large swaths of the global population, leaving the survivors without sufficient means to rebuild society to current standards of living".[1]

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What risk types are described in this timeline?

- Sort the full timeline by "Risk type".

- You will see both multiple risk types covered in one event, and single types, often impact events and nuclear weapons. Scientific concepts, such as entropy, are also included in this column.

- What are some notable or sample conducted studies in the field of existential risk or directly related fields and sub-fields?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Research".

- What are some organizations engaged in the study and prevention of global catastrophic risks?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Organization".

- You will mostly see organizations engaged in preventing existential risks from multiple causes, but also some organizations specialized in one risk type.

- What are some notable cases of incidents representing the possibility of global catastrophic risks at a major scale?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Sample case".

- What are some events describing the probability of occurrence of a global catastrophic risks?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Probability".

- You will see some calculations of risk, mainly on nuclear warfare and artificial intellicence.

- What are some notable or sample publications on the topic?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Literature".

- You will see a variety of publications, some treating the entire field of existential risk, and others specializing in one risk type.

- What are some notable comments from prominent personalities, regarding the topic of existential risk?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Notable comment".

- You will see comments by prominent people in the field of existential risk, such as Nick Bostrom, but also prominent personalities, like Albert Einstein and H.G. Wells.

- What are some concepts introduced in relation to the topic of existential risk?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Concept development".

- You will see the emergence of concepts related to the field, such as "existential risk", "supervolcano", etc.

- What are some programs aimed to preserve species, data, and information, in case a catastrofic risk threatens their existence?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Preservation effort".

- You will see some notable projects, such as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

- What are other programs launched by competitive entities with the purpose to combat existential risks?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Program launch".

- You will mostly see programs launched to prevent impact events. Programs adressing other existential risks are also described.

- Other events are described under the following types: "Budget", "Conference", "Document", "Field development", "Field growth", "Filmmaking", "International law", "Milestone event", "Open leter", "Policy", "Politics", "Project launch", "Scientific wager", "Space colonization", and "Statistics".

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 19th century–1945 | Early development | Concerns about human extinction can be traced back to the 19th century[2], with geology unveiling a radically nonhuman past.[3] French scientist Georges Cuvier popularizes the concept of catastrophism in the early 1800s. The first near-Earth asteroid is discovered. Toward the first half of the twentieth century, chemical and biological weapons become a case of concern. |

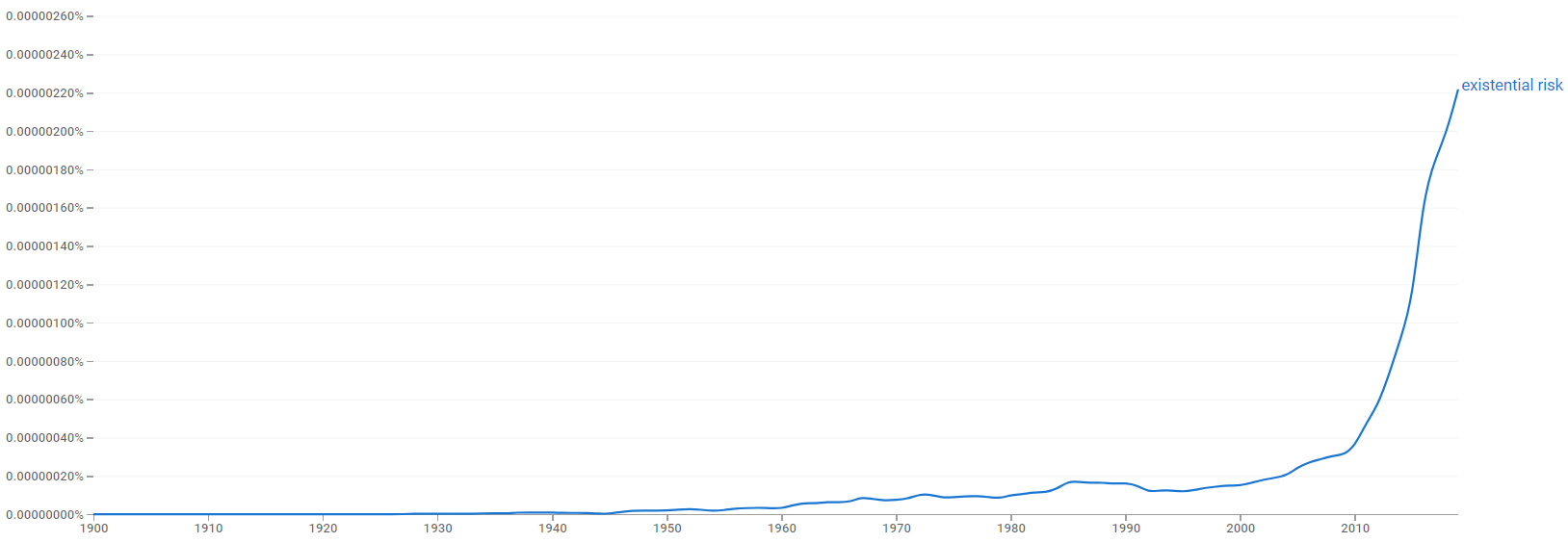

| 1945 onwards | Atomic Age/anthropocene | The nuclear holocaust becomes a theoretical scenario shortly after the beginning of this age, which starts following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon. In the 1950s, humanity enters a new age, facing not only existential risks from our natural environment, but also the possibility that we might be able to extinguish ourselves. During the 1960s, mutual assured destruction leads to the expansion of nuclear-armed submarines by both Cold War adversaries.[4] In the same decade, the anti-nuclear movement launches, and the environmentalist movement soon adopts the cause of fighting climate change.[5] Supervolcanoes are discovered in the early 1970s.[6] Global warming becomes widely recognized as a risk in the 1980s.[7] The term "existential threat", beginning to spread around the 1960–80s during the Cold War, takes off in the 1990s and early 2000s.[8] |

| 21st century | Field of study consolidation | Nick Bostrom introduces the term "existential risk", which emerges as a unified field of study.[2] By the early 2000s, scientists identify many other threats to human survival, including threats associated with artificial intelligence, biological weapons, nanotechnology, and high energy physics experiments.[2] Unaligned artificial intelligence is recognized by some as the main threat within a century.[7] Today, it is understood that the natural risks are dwarfed by the human-caused ones, turning the risk of extinction into an especially urgent issue.[5] |

Full timeline

| Year | Risk type | Event type | Details | Country/location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slightly over 66 million years ago | Impact event | Sample case | The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event occurs when a large asteroid, about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) in diameter, strikes Earth, causing a mass extinction in which 75% of plant and animal species on Earth became extinct, including all non-avian dinosaurs.[9] | Mexico (Yucatán Peninsula) |

| 1490 | Impact event | Sample case | The Ch'ing-yang event occurs as a meteor shower or air burst in Qingyang, China.[10] More than 10,000 people are estimated to be killed by the meteoric event.[11] | China |

| 1577 | Impact event | Research | Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe tries to measure the distance of a comet through its parallax. After this, the extraterrestrial nature of comets is recognized and confirmed.[12] | Denmark |

| 1694 | Impact event | Research | English astronomer Edmond Halley presents a theory that Noah's flood in the Bible was caused by a comet impact.[13] | United Kingdom (Kingdom of England) |

| 1763 | Multiple | Concept development | English statistician Thomas Bayes' solution to a problem of inverse probability is presented in the publication of An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances.[14] The Bayes theorem describes the probability of an event, based on prior knowledge of conditions that might be related to the event, thus providing rules for thinking about probabilities prior to any trials.[15] | United Kingdom |

| 1777 | Heat death of the universe | Research | French astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly becomes the first to put forward the conjecture that all bodies in the universe cool off, eventually becoming too cold to support life.[16][17] | France |

| 1778 | Multiple | Literature | French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste Georges Buffon publishes Les époques de la nature, which theorizes that the Earth was created by molten matter expelled from the Sun. Buffon also provides first experimental calculations of the window of planetary habitability, arguing that eventually Earth will become irreversibly uninhabitable.[18] | |

| 1798 | Overpopulation | Literature | English cleric, scholar and economist Thomas Robert Malthus publishes An Essay on the Principle of Population, which mathematically demonstrates the relationship between food and human population. Malthus argues that whenever food supply increases, population rapidly grows to eliminate the abundance resulting in perpetual human suffering unless we control human population.[19] Human overpopulation is considered a global catastrophic risk in the domain of earth system governance.[20] | United Kingdom |

| 1800 | Multiple | Research | French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier publishes paleontological paper under the title Mémoires sur les espèces d'éléphants vivants et fossiles. Cuvier demonstrates that elephantine bones unearthed in Siberia and North America belonged to mammoths and mastodons. Prior to this, the scientific community largely rejected the possibility that species could go extinct.[2] | France |

| 1815 | Supervolcano | Sample case | Mount Tambora erupts in the island of Sumbawa, dispersing volcanic ash around the world and lowering global temperatures in an event sometimes known as the Year Without a Summer. Extreme weather and harvest failures follow, causing famine in China and Europe and triggering cholera outbreak in Bengal.[3] | Indonesia |

| 1826 | Pandemic | Literature | English novelist Mary Shelley publishes The Last Man, which depicts Europe in the late 21st century, ravaged by a mysterious plague pandemic that rapidly sweeps across the entire globe, ultimately resulting in the near-extinction of humanity. This is first modern post-apocalyptic pandemic novel[21], and the first proper depiction of an existential catastrophe where nonhuman ecosystems continue after demise of humanity.[3] | United Kingdom |

| 1844 | Omnicide | Concept development | Russian prince Vladimir Odoevsky writes a short story in which a future humanity, stricken with overpopulation and resource-depletion, welcomes a ‘Last Messiah’ who instructs a jaded mankind to commit omnicide by blowing up the planet.[22] According to Thomas Moynihan, this is the first speculation on omnicide.[3] | |

| 1859 | Nature | Literature | Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species, which would succed in convincing the scientific community that evolution is a fact about the history of all Earth-originating life, metaphysically integrating humanity into the natural order. Before this book, the belief that an ontological gap separates humans from nature was prominent.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1863 | Weapons of mass destruction | Deterrence theory | French science fiction writer Jules Verne imagines a world in which “the engines of warfare were perfected to such a degree” that they brought peace to the world. The topic of deterrence theory, which is anticipated by Verne, would gain relevance in the atomic age. The general consensus is that, in theory, no one would have an incentive to start a nuclear war as long as no one could win.[4] | France |

| 1893 | Multiple | Literature | Science fiction author H. G. Wells writes two non-fiction essays about the topic of human extinction, On Extinction and The Extinction of Man, though both clearly draw as much on his literary imagination as his scientific method.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1898 | Impact event | Research | 433 Eros is discovered by German astronomer C.G. Witt at the Berlin Observatory in an eccentric orbit between Mars and Earth.[23] It is the first near-Earth asteroid to be discovered.[24] | Germany (Berlin Observatory) |

| 1901 | Multiple | Literature | H. G. Wells publishes Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought, followed by The Discovery of the Future. Both texts can be considered foundational for the academic field of Futures Studies. Wells contends that the scientific method can and should be used to predict future events, trends, and outcomes. He believes that by understanding the past and present, we can make more informed decisions about the future.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1903 | Multiple | Notable comment | English writer H.G. Wells gives a lecture at the Royal Institution, highlighting the risk of global disaster. Wells states:

Wells' pessimism would deepen in his later years, as he would live long enough to learn about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki before dying in 1946.[25] |

United Kingdom |

| 1906 | Geomagnetic reversal | Research | Magnetic field reversal is discovered. This is a major discovery as it shows that the Earth's magnetic field is not always the same.[26] | |

| 1907 | Multiple | Research | English utilitarian philosopher and economist Henry Sidgwick becomes the first to note that human extinction would be “the greatest of conceivable crimes from a Utilitarian point of view. Total utilitarianism implies that humanity should not only strive for happiness, but create as much well-being as possible, including through the creation of as many humans with positive well-being as possible.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1908 | Impact event | Sample case | The Tunguska event occurs when an asteroid of about 200 feet in diameter explodes above Siberia with the force of a hydrogen bomb that would have have killed millions of people had it exploded above a major city. A much larger asteroid among the thousands of dangerously large objects in orbits that intersect the earth’s orbit, could strike the earth and cause the total extinction of humanity through a combination of shock waves, fire, tsunamis, and blockage of sunlight, wherever it struck.[25] | Russia |

| 1922 | Technology | Research | German bacteriologist and anthropologist Paul Alsberg hypothesizes that human progress resulted in ‘physiological regression’. This is, instead of bodily adaptation, the evolutionary selection process in humans have shifted to the extra-bodily evolution of our technical tools, which triggers an ‘atrophy of the body’ as the ‘immediate consequence of it being superseded by the artificial tool’.[3]: Loc 5629 | |

| 1924 | Multiple | Literature | British statesman Winston Churchill publishes Shall We All Commit Suicide?, which would be considered an example of pure journalism helping to build the field of existential risk.[2] In his essay, Churchill argues that human survival depends on setting aside selfish materialism in favor of developing our capacities for “Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love”.[27] | United Kingdom |

| 1925 (June 17) | Weapons of mass destruction (chemical weapon,biological weapon) | International law | The Geneva Protocol is signed with the purpose to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons.[28] It would enter into force on 8 February 1928.[29] | |

| 1929 | Ultimate fate of the universe | Research | Edwin Hubble publishes his conclusion, based on his observations of Cepheid variable stars in distant galaxies, that the universe is expanding. From then on, the beginning of the universe and its possible end would be subjects of serious scientific investigation.[30] | United States |

| 1937 | Impact event | Sample case | Asteroid 69230 Hermes is discovered when it passes the Earth at twice the distance of the Moon.[31] | |

| 1945 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Organization | The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is founded by Manhattan Project scientists at the University of Chicago[32][33], upon being concerned about the consequences of their work. Two years later, the bulletin would create the iconic “Doomsday Clock”.[2] | United States |

| 1937 | Omnicide | Literature | British writer Olaf Stapledon publishes science fiction novel Star Maker, which synthesizes ideas on longtermism into a comparative study of omnicide.[3] | United Kingdom |

| 1945 (July 16) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Milestone event | The first nuclear detonation is conducted when a plutonium implosion device is tested at a site located 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico. Many scientists would suggest dating the beginning of the Anthropocene age to this event, stating that that Homo sapiens gained a position of unprecedented influence over the Earth system.[34] | United States |

| 1945 (August 6) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Milestone event | Hiroshima becomes the first city targeted by a nuclear weapon, when the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) drops the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on the city.[35] | Japan |

| 1945 (August 9) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Milestone event | Nagasaki becomes the second and, to date, last city in the world to experience a nuclear attack, when the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) drops the atomic bomb "Fat Man" on the city.[36] | Japan |

| 1945 (August 18) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature (article) | Bertrand Russell publishes The Bomb and Civilization, which he had begun writing the day Nagasaki was bombed.[37] Russell writes:

|

United Kingdom |

| 1947 | Impact event | Organization | The Minor Planet Center is established by the International Astronomical Union at Cincinnati Observatory. It is responsible for collecting and disseminating positional measurements and orbital data for asteroids (minor planets) and comets.[39] | United States |

| 1947 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Probability | The Doomsday Clock is introduced, and set seven minutes to midnight.[40] It is a symbol that represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe, in the opinion of the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.[41] | |

| 1948 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Notable comment | Albert Einstein writes:

| |

| 1948 | Overpopulation | Literature | American ecologist William Vogt publishes Road to Survival[2], which argues that human population control is necessary to avoid an ecological catastrophe. This book constitutes an early warning of the dangers of overpopulation.[42] | |

| 1948 | Environmental disaster | Literature | American conservationist Henry Fairfield Osborn Jr. publishes Our Plundered Planet[2], which warns of the environmental destruction caused by human activity. It is considered one of the earliest works on the subject of environmentalism.[43] | |

| 1949 | Supervolcano | Concept development | The term "supervolcano" is first used in a volcanic context.[44] | |

| 1950 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Research | In a letter to the editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Leo Szilard warns that it would be possible to rig an H-bomb with materials that would create enough fallout to kill everyone on earth. This would become known as a "cobalt bomb."[45] | United States |

| 1954 (March 1) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Milestone event | The United States tests its largest thermonuclear weapon test in Bikini Atoll; the detonation being code-named “Castle Bravo”.[46] | United States |

| 1955 | Multiple | Literature (article) | Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann publishes an article entitled Can We Survive Technology?[47][48], which alerts on the threats that may result from ever-expanding technological progress in a finite world.[49] Von Neumann discusses nuclear weapons, nuclear power, climate control, and automated systems, and believes that the difficulties and opportunities facing humanity are of great importance in having a bearing on future events.[50] | United States (Fortune magazine) |

| 1955 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | A group of prominent scientists, including Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein, write what would come to be known as the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, according to which: “No one knows how widely such lethal radioactive particles might be diffused, but the best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with H-bombs might possibly put an end to the human race… sudden only for a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.”[2] | |

| 1958 | Multiple | Literature | German mathematician Emil Julius Gumbel publishes Statistics of Extremes, which would become an important classic in extreme value theory, a branch of statistics dealing with the extreme deviations from the median of probability distributions.[51] | |

| 1960 | Impact event | Scientific development | American geologist Eugene Merle Shoemaker definitively proves that some of the Earth’s craters were produced not by geological activity, but by vast meteoric impacts, far beyond any in recorded history.[26] | United States |

| 1960 | Multiple | Concept development | English-American theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson in his paper Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation popularizes the concept of the later called Dyson sphere, a hypothetical megastructure that completely encompasses a star and captures a large percentage of its solar power output. Dyson speculates that such structures would be the logical consequence of the escalating energy needs of a technological civilization and would be a necessity for its long-term survival.[52] | United States |

| 1960 (October 5) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | The world goes at the brink of nuclear war when a radar alert from Thule, Greenland is sent to the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), announcing the detection of dozens of Soviet missiles launched for the United States.[53] NORAD headquarter in Colorado goes into a panic, but the latter is put to rest when it is realized that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev is visiting New York at the time. It would be later determined that the radar had mistaken the moon rising over Norway as Soviet missiles.[54] | Greenland, United States |

| 1960 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Concept development | American nuclear physicist Herman Kahn introduces the concept "doomsday machine" in his book On Thermonuclear War. It is a hypothetical device that would automatically trigger a global nuclear holocaust in response to a nuclear attack.[55] | United States |

| 1960 | Overpopulation | Concept development | Austrian American scientist Heinz von Foerster and his colleagues P. M. Mora and L. W. Amiot publishe their Doomsday equation formula in Science, predicting future population growth. The formula represents a best fit to available historical data on world population, and the authors then predict future population growth on the basis of this formula, which gives 2.7 billion as the 1960 world population and predicts that population growth would become infinite by Friday, November 13, 2026 – von Foerster's 115th birthday anniversary – a prediction that would earn it the name "the Doomsday Equation."[56] | United States |

| 1961 (April 12) | Multiple | Space colonization | Soviet pilot and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes the first human to journey into outer space[57], becoming also the first human face for space exploration, giving hope to humanity to survive outside of earth.[58][59] | Soviet Union |

| 1961 | Scorched earth, multiple | Literature (article) | German astrophysicist Sebastian von Hoerner publishes an article entitled The Search for Signals from Other Civilizations, which discusses various factors that might affect the longevity of technological races and what this in turn would mean for the chances of success of SETI programs.[60] Von Hoerner suggests that sixty percent of all civilisations immolate themselves in planet-scorching war.[61][3]: 244 In the following years, he would expand his speculations on the longevity of civilizations, and the existential 'crises' they face, concluding that the civilizations that don't destroy themselves will instead face "irreversible stagnation".[62] | Germany (Astronomical Calculation Institute (Heidelberg University) |

| 1961 (November 24) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | On an evening, communication links between Strategic Air Command headquarters (SAC HQ) and NORAD go dead, resulting in the lost communication with three Ballistic Missile Early Warning Sites (BMEWS) around the world, all of which were supposed to run on independent telephone and telegraph lines.[63] | United States |

| 1962 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Concept development | Herman Kahn's Hudson Institute strategist Donald Brennan coins the term "mutual assured destruction", commonly abbreviated "MAD".[64], a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy in which a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender.[65] | |

| 1962 | Climate change | Literature | Rachel Carson publishes Silent Spring, which warns of the potential dangers of pesticide use.[66] Considered a pivotal early work, this book would become immensely popular, in addition to increasing scientific rigour and raising public awareness about the danger from chemical pesticides, such as DDT, chlordane, and heptachlor.[2] | United States (Houghton Mifflin) |

| 1962 (October 27) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Probability | During the Cuban Missile Crisis, after a Soviet submarine B-59 loses contact with Moscow for days, the captain orders the use of a nuclear torpedo when a US ship begins dropping practice depth charges to make the submarine surface, with the Russian captain mistaking them for real depth charges, and concluding that war has begun. Aboard commander Vasili Arkhipov countermands the order to fire, thus preventing the nuclear strike and potentially an all-out nuclear war.[67][4] During the crisis, United States President John F. Kennedy would estimate the probability of escalation to nuclear conflict as between 33% and 50%.[68][69] | Cuba, United States, Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1963 (August 5) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | International law | The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty is signed with the purpose to ban all nuclear weapons tests except for those conducted underground.[70] It would enter into force on October 10, 1963.[71] With the signing of this treaty, the Doomsday Clock is moved back to twelve minutes to midnight.[4] | |

| 1964 | Multiple | Notable comment | Soviet astrophysicist Iosif Shklovsky writes:

|

Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1964 | Impact event | Literature | Dandridge M. Cole and Donald W. Cox publish Islands in Space, which notes the dangers of planetoid impacts, both those occurring naturally and those that might be brought about with hostile intent. The authors argue for cataloging the minor planets and developing the technologies to land on, deflect, or even capture planetoids.[73] | United States |

| 1966 | Artificial intelligence | Research | British mathematician Irving Good publishes paper entitled Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine, which posits that such AI would be “the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”[2] Good speculates that artificial general intelligence might bring about an intelligence explosion.[74] | United Kingdom |

| 1967 (January 27) | Weapons of mass destruction | International law | The Outer Space Treaty is opened for signature in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, with the purpose to ban stationing of weapons of mass destruction in space.[75] It would enter into force on October 10, 1967.[76] | United States, United Kingdom, Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1967 (May 23) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | A major solar flare causes radars at all three Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) sites in the far Northern Hemisphere to become jammed, the latter being a signal of attack.[77] | United States |

| 1967 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Notable comment | Hungarian-British essayist Arthur Koestler writes:

|

United Kingdom |

| 1967 | Impact event | Research | Students in the Aeronautics and Astronautics department at MIT conduct a design study, "Project Icarus", of a mission to prevent a hypothetical impact on Earth by asteroid 1566 Icarus.[79] The design project would be later published in a book by the MIT Press[80] and receive considerable publicity, for the first time bringing asteroid impact into the public eye.[81] | |

| 1968 (July 1) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | International law | The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty is signed to prevent nuclear proliferation, promote nuclear disarmament, and promote peaceful uses of nuclear energy.[82] It would enter into force on March 5, 1970.[83] | Rusia (Moscow, United Kingdom (London), United States (Washington D.C.) |

| 1968 | Overpopulation | Literature | American biologist Paul R. Ehrlich publishes The Population Bomb.[84] This book would receive wide public attention, warning about the catastrophic impacts of overpopulation, and arguing that human overpopulation would lead to widespread famine by the 1970s and 1980s.[2] | United States |

| 1969 | Gamma-ray burst | Scientific development | Scientists discover a new and distinctive type of stellar explosion[26] when the first gamma-ray burst is found.[85] A high-energy astronomical event, its release of vast amounts of energy could conceivably harm biospheres at astronomical distances, with radiation penetrating the atmosphere, a resulting ultraviolet flash, possible Air shower (physics), and formation of nitrous oxides that deplete the ozone layer, producing acid rain, and causing multiyear cooling climate effects that if, intense enough, could plausibly cause a mass extinction.[86] | |

| 1969 | Weapons of mass destruction (biological weapon) | Literature (article) | Just prior to Richard Nixon announcement of new U.S. initiatives towards the regulations of biological weapons[87], Joshua Lederberg of Stanford University publishes Biological warfare and the extinction of man, which argues that the use of biological weapons could lead to the extinction of humanity. Leberberg cites the uncontrollable nature of infectious agents compared to nuclear weapons, which allow the possibility at least to be confident of the laws of scaling, as the destruction of targets can be calculated from simple physical measures like the energy released, a control impossible to apply to biological weapons.[2][88] | United States (Stanford University) |

| 1969 (July 20) | Multiple | Space colonization | United States astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin land the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle, and Armstrong becomes the first person to step onto the Moon. This is another milestone event towards space colonization, which can be considered a hedge against existential risk.[89] | United States |

| 1971 (February 11) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | International law | The Seabed Arms Control Treaty is signed, with the purpose to ban stationing of weapons of mass destruction on the ocean floor. It would enter into force on May 18, 1972.[90] | |

| 1972 (April 10) | Weapons of mass destruction (biological weapon) | International law | The Biological Weapons Convention is signed, with the purpose to comprehensively ban biological weapons.[91] It would enter into force on March 26, 1975.[92] | |

| 1972 | Multiple | Preservation effort | The San Diego Zoo establishes the first "frozen zoo" program. A “frozen zoo” is a cryonic facility for the long term preservation of animal and plant genetic material such as skin cells, DNA, sperm, eggs, and embryos.[93] | United States |

| 1972 | Economic growth | Literature | The Club of Rome publishes a report called The Limits to Growth[3], which warns of the dangers of unchecked economic growth. The report suggests that the world was on a path to economic and environmental disaster, and that action needed to be taken to prevent this. Its conclusions are stark: “If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years.”[2] | |

| 1974 (August 1) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | As a result of the Watergate scandal, United States President Richard Nixon becomes clinically depressed, emotionally unstable, and drinking heavily. As a mode of precaution U.S. Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger instruct the Joint Chiefs of Staff to route “any emergency order coming from the president”—such as a nuclear launch order— through him first.” [94] | United States |

| 1975 | Multiple | Concept development | American astrophysicist Michael H. Hart publishes an early detailed examination of the Fermi paradox.[95][96]: 27–28 [97]: 6 He argues that if intelligent extraterrestrials exist, and are capable of space travel, then the galaxy could have been colonized in a time much less than that of the age of the Earth. However, there is no observable evidence they have been here, which Hart called "Fact A".[97]: 6 | United States |

| 1976 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Notable comment | Iosif Shklovsky argues that global self-destruction is the result of capitalist ideology, which doesn't take into account a potential ‘communist transformation of society’ which would ‘remove the very possibility of such crisis situations’.[98] | Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1979 | Climate change | Research | The range of climate sensitivity is first put forward from 1.5°C to 4.5°C, a range adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and that would barely change over the next forty years.[99] | Worldwide (United Nations) |

| 1979 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | The United States Congress' Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) publishes The Effects of Nuclear War,[100] a study examining the full range of effects that nuclear war would have on civilians: direct effects from blast and radiation; and indirect effects from economic, social, and politicai disruption. Particular attention is devoted to the ways in which the impact of a nuclear war would extend over time.[101] | United States |

| 1979 | Multiple | Literature | Isaac Asimov publishes A Choice of Catastrophes: The Disasters That Threaten Our World, an early book-length nonfiction treatment of possible existential catastrophes.[2] | United States |

| 1979 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | American engineer Cresson Kearny publishes Nuclear War Survival Skills: Lifesaving Nuclear Facts and Self-Help Instructions, which aims to provide a general audience with advice on how to survive conditions likely to be encountered in the event of a nuclear catastrophe, as well as encouraging optimism in the face of such a catastrophe by asserting the survivability of a nuclear war.[102] | United States |

| 1980 | Collapse of the vacuum | Scientific development | Theoretical physicists Sidney Coleman and Frank De Luccia calculate for the first time that any bubble of true vacuum would immediately suffer total gravitational collapse.[103][104] | United States |

| 1980 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Research | The earliest appearance of a connection between space exploration and human survival appears in Louis J. Halle, Jr.'s article in Foreign Affairs, in which he states colonization of space will keep humanity safe should global nuclear warfare occur.[105] | United States |

| 1980 | Impact event | Organization | Spacewatch is founded by Tom Gehrels and Robert S. McMillan as a research group of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory of the University of Arizona in Tucson, with the purpose to be the first to use electronic detectors to discover NEAs and to explore the various populations of small objects in the solar system.[106][107] | United States |

| 1980 | Impact event | Scientific development | A team of scientists led by Luis Walter Alvarez and his son Walter Alvarez discover that the geological boundary between the Cretaceous and Palaeogene periods is rich in iridium, an element markedly more common in asteroids than on the Earth’s surface, where it's extremely rare. The team concludes with what would be called the Alvarez hypothesis, which posits that the impact of a large asteroid on the Earth could have caused the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which killed the dinosaurs.[26][2] | United States |

| 1980 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | Survival expert Bruce Clayton publishes Life After Doomsday[108], which attempts to provide a comprehensive guide to surviving a nuclear disaster, including detailed instructions on how to build and defend a shelter, store food, treat illnesses and injuries, and cope with the psychological effects of such an event.[109] | United States}} (Paladin Press) |

| 1980 | Multiple | Scientific wager | In what is known as the Simon–Ehrlich wager, American professor Julian Simon and American biologist Paul Ehrlich, bet on the future of natural resource prices as a vehicle for their public debate about mankind's future. Simon challenges Ehrlich, which dismisses and mocks the optimistic views of Simon, to a wager over a 10-year period, to judge who was right about resource availability. Simon would ultimately win, and his victory would be used as evidence that innovation can offset material scarcity induced by human economic activity.[110] On a deeper level, the Simon–Ehrlich wager can be regarded as a conflict of visions concerning the future of humanity.[111] | United States |

| 1981 | Impact event | Field development | Inspired by the Alvarez hypothesis, American astronomer Carolyn S. Shoemaker convenes a seminal meeting, founding the scientific field of impact hazards.[26] | United States |

| 1981 | Pandemic | Sample case | HIV/AIDS is first recognized with reports of an unusual pneumonia in men who have sex with men caused by Pneumocystis carinii and previously seen almost exclusively in immunocompromised subjects.[25] For years this disease would remain a death sentence, spreading to all continents and lowering life expectancy in many countries in Africa.[112] | |

| 1982 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | American author Jonathan Schell publishes The Fate of the Earth, which would be regarded as a key document in the nuclear disarmament movement.[113] By the time of this publication, there are almost 60,000 nuclear weapons stockpiled with a destructive force equal to roughly 20,000 megatons (20 billion tons) of TNT, or over 1 million times the power of the Hiroshima bomb.[25][2] | United States |

| 1983 | Multiple | Research | American historian W. Warren Wagar argues that science fiction played a significant role in the development of the academic field of futures studies.[2] | United States |

| 1983 | Multiple | Concept development | British cosmologist Brandon Carter frames the "Doomsday argument", a probabilistic argument that claims to predict the future number of members of the human species given an estimate of the total number of humans born so far.[114] | United Kingdom |

| 1983 (September 26) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | A newly inaugurated Soviet early-warning satellite system causes a nuclear false alarm, leading to widespread panic and confusion.[115] | Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1984 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich publish The Cold and the Dark, a book discussing long-term biological consequences of nuclear war.[2] | |

| 1984 | Bioterrorism | Sample case | The Rajneeshee bioterror attack occurs when a group of prominent followers of Rajneesh spread the enteric bacterium, Salmonella typhimurium, onto salad bars in The Dalles, Oregon, causing illness in over 750 people and sending many to hospitals.[25] | United States |

| 1984 | Multiple | Literature | British philosopher Derek Parfit publishes Reasons and Persons, which partly discusses population ethics. It raises questions about whether it can be wrong to create a life, whether environmental destruction violates the rights of future people, and so on.[116] | |

| 1985 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Politics | 54-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev is appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. While his full intentions would remain unclear, Gorbachev's moderate liberalization measures would result in the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[25] Historian Yuval Noah Harari would call Gorbachev an historical hero, for probably saving the world from nuclear war.[117] | Russia (Soviet Union) |

| 1986 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Statistics | The global size of the nuclear arsenals peaks at 70,000 warheads.[26] | Countries with nuclear weapons |

| 1986 | Nanotechnology | Concept development | Nanotechnology pioneer K. Eric Drexler coins the term gray goo in his book Engines of Creation.[118] Gray goo is a hypothetical global catastrophic scenario involving molecular nanotechnology in which out-of-control self-replicating machines consume all biomass on Earth while building more of themselves[119], a scenario that would be called ecophagy (the literal consumption of the ecosystem).[120][25][2] | |

| 1986 | Technology | Organization | The Foresight Institute is founded by K. Eric Drexler "to help prepare society for anticipated advanced technologies", mainly nanotechnology.[121][122] | |

| 1986 | Multiple | Organization | The Center for Security and International Cooperation is formed at Stanford University.[123] It is a hub for researchers tackling some of the world's most pressing security and international cooperation problems.[124] | United States |

| 1986 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | Lydia Dotto publishes Planet Earth in Jeopardy: Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War, A distillation of the report by the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE), written for a lay audience. It explores the climatic and atmospheric changes induced, radiation and fallout, and the putative biological consequences of nuclear war.[125] | |

| 1987 | Technology | Research | American political scientist Aaron Wildavsky proposes that cultural orientations such as egalitarianism and individualism frame public perceptions of technological risks. Since then, a body of empirical research would grow to affirm the risk-framing effects of personality and culture.[25] | United States |

| 1987 (September 16) | Multiple | The Montreal Protocol is an international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion. Entering into force on 1 January 1989, it would result in the ozone hole in Antarctica slowly recovering. This can be considered an example of global coordination resulting in positive outcome. | All United Nations members, as well as the Cook Islands, Niue, the Holy See, the State of Palestine and the European Union | |

| 1988 | Impact event | Progream launch | The United States, the European Union, and other nations begin scanning the sky for near-earth objects in an effort called Spaceguard.[126] | United States, European Union, other |

| 1988 | Climate change | Organization | American scientist James Hansen testifies to the United States Congress that climate change is already underway. In the same year, the World Meteorological Organization establishes the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which would since produce five reports summarizing the state of the science on climate change.[4] | United States |

| 1988 | Supervolcano | Research | According to Rampino et al., the injection of massive amounts of volcanic dust into the stratosphere by a super-eruption such as Toba might be expected to lead to immediate surface cooling, creating a volcanic winter.[127] [25] | |

| 1989 (March 23) | Impact event | Sample case | 300 m (980 ft) diameter Apollo asteroid 4581 Asclepius (1989 FC) misses the Earth by 700,000km. If the asteroid had impacted it would have created the largest explosion in recorded history, equivalent to 20,000 megatons of TNT. This event would attract widespread attention because it was discovered only after the closest approach.[128] | |

| 1991 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | The Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program is initiated upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when the risk of "loose nukes" prompts a new wave of government, academic, and popular concern about nuclear terrorism. The program provides funding and expertise to partner governments in the former Soviet Union to secure and eliminate weapons of mass destruction at the source.[129][25] | |

| 1991 | Multiple | Project launch | Biosphere 2 is completed. It is a massive scientific facility meant to simulate Earth's ecosystems.[130] It is originally meant to demonstrate the viability of closed ecological systems to support and maintain human life in outer space as a substitute for Earth's biosphere.[131] | United States |

| 1992 | Multiple | Document | The World Scientists' Warning to Humanity is writen by Henry Way Kendall, a former chair of the board of directors of the Union of Concerned Scientists, and signed by about 1,700 leading scientists, including a majority of the Nobel Prize laureates in the sciences.[132] | United States |

| 1992 | Greenhouse effect | Research | According to Caldeira and Kasting, the end of complex life may come in 0.9-1.5 billion years owing to the runaway greenhouse effect.[25] According to the researchers, when the Sun becomes too bright, it will drive a runaway greenhouse effect through the Earth’s atmosphere.[25][133] | United States |

| 1992 | Impact event | Recommendation | In a report to NASA, a coordinated Spaceguard Survey is recommended to discover, verify and provide follow-up observations for Earth-crossing asteroids. This survey is expected to discover 90% of these objects larger than one kilometer within 25 years.[134] | United States (NASA) |

| 1992 | Bioterrorism | Sample case | The doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo sends a medical team to Zaire in what would be believed to have been an attempt to procure Ebola virus[135]. While an unsuccessful attempt, this event provides an example of a terrorist group apparently intending to make use of a contagious virus.[25] | Japan, Congo DR |

| 1992 (September 3) | Weapons of mass destruction (chemical weapon) | International law | The Chemical Weapons Convention is signed to comprehensively ban chemical weapons.[136] It would enter into force on April 29, 1997.[137] | |

| 1993 | Bioterrorism | Sample case | The United States Congress' Office of Technology Assessment finds that a single 100 kg load of anthrax spores, if delivered by aircraft over a crowded urban setting, depending on weather conditions, could result in fatalities ranging between 130,000 and 3 million individuals.[25] | United States |

| 1993 | Impact event | Research | American geophysicist H. J. Melosh with I. V. Nemchinov propose deflecting an asteroid or comet by focusing solar energy onto its surface to create thrust from the resulting vaporization of material.[138] | United States |

| 1994 | Impact event | Program launch | The United States Congress issues NASA the directive to find and track 90 percent of all near-Earth Objects greater than one kilometer across, a task that would be completed in 2011, for a total cost of less than $70 million.[139][26] | United States |

| 1995 | Impact event | Recommendation | A NASA report recommends search surveys that would discover 60–70% of short-period, near-Earth objects larger than one kilometer within ten years and obtain 90% completeness within five more years.[140] | United States (NASA) |

| 1995 | Impact event | Program launch | Following the 1994 Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet impacts with Jupiter, Edward Teller proposes, to a collective of U.S. and Russian ex-Cold War weapons designers in a planetary defense workshop meeting at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), that they collaborate to design a one-gigaton nuclear explosive device, which would be equivalent to the kinetic energy of a 1km diameter asteroid.[141][142][143] | United States |

| 1995 (January 25) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Sample case | The Norwegian rocket incident occurs when a Norwegian-U.S. scientific weather rocket is mistaken by Russian radar operators for a nuclear attack.[144] Russian President Boris Yeltsin is prompted to activate his nuclear briefcase to contemplate launching in retaliation. [145] | Russia |

| 1995 | Impact event | Research | The concept of asteroid laser ablation is articulated in a white paper entitled Preparing for Planetary Defense. Similar to the effects of a nuclear device, it is thought possible to focus sufficient laser energy on the surface of an asteroid to cause flash vaporization/ablation to create either in impulse or to ablate away the asteroid mass.[146] | |

| 1995 | Bioterrorism | Sample case | The Tokyo subway sarin attack occurs when members of the cult movement Aum Shinrikyo released sarin on three lines of the Tokyo Metro, killing 13 people, and severely injuring 50.[147] ReligiousTolerance.org says that Aum Shinrikyo is the only religion known to have planned Armageddon for non-believers.[148] | Japan |

| 1996 (March 26) | Impact event | Organization | The Spaceguard Foundation is established in Rome.[149] It works to promote and coordinate activities for the discovery and characterization of near-Earth objects.[150] | Italy |

| 1996 | Multiple | Literature | Canadian philosopher John A. Leslie publishes The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction, which examines the various ways that humanity could come to an end, such as through nuclear war, environmental disaster, or disease, and evaluates the ethical implications of each.[151] This work contributes to the foundation of the field of existential risk studies.[2] Leslie estimates that if the reproduction rate drops to the German or Japanese level the extinction date will be 2400.[151] | United Kingdom (Routledge) |

| 1996 | Multiple | Preservation effort | The Millennium Seed Bank Partnership begins. It is an international conservation project with the purpose to provide an "insurance policy" against the extinction of plants in the wild by storing seeds for future use in large underground frozen vaults preserving the world's largest wild-plant seedbank or collection of seeds from wild species.[152] | United Kingdom |

| 1996 | Impact event | Research | Planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker proposes deflecting a potential impactor by releasing a cloud of steam in the path of the object, hopefully gently slowing it.[153] | |

| 1996 | Supervolcano | Research | According to Bekki et al., volcanic aerosols have a longer residence time of several years compared to a few months for fine dust, therefore a huge eruption might be expected to have a longer lasting effect on global climate than an impact producing a comparable amount of atmospheric loading.[25] | |

| 1996 (September 10) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | International law | The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty is signed to ban all nuclear weapons tests.[154] As of 2022, it is not in force.[155] | |

| 1997 | Climate change | Research | According to Toon et al., the major effect on civilization would be through collapse of agriculture as a result of the loss of one or more growing seasons. This would be followed by famine, the spread of infectious diseases, breakdown of infrastructure, social and political unrest, and conflict.[25] | |

| 1997 | Epizootic | Sample case | An outbreak in Taiwan of the highly contagious foot-and-mouth disease, causes the slaughter of 8 million pigs and brings exports to a halt, with estimated costs of $20 billion. This case exemplifies how threats to agriculture, livestock, and crops, which can cause major economic damage and loss of confidence in food security, should not be overlooked.[25] | Taiwan |

| 1998 | Impact event | Program launch | The United States Congress gives NASA a mandate to detect 90% of near-earth asteroids over 1km diameter (that threaten global devastation).[156][157] | United States (NASA) |

| 1998 (August 13) | Multiple | Organization | The Mars Society is founded by Robert Zubrin. It is a nonprofit organization that works to educate the public, the media and the government on the benefits of exploring Mars and creating a permanent human presence on the planet. Headquartered in Lakewood, Colorado, it is based on Zubrin's Mars Direct plan, which aims to make human mission to Mars as lightweight and feasible as possible.[158] Members include Buzz Aldrin and Elon Musk. | United States |

| 1998 (December 6) | Artificial intelligence | Research | In one message from Nick Bostrom to artificial intelligence theorist Eliezer Yudkowsky on the Extropians mailing list[159], inline quotations show Yudkowsky arguing that it would be good to allow a superintelligent AI system to choose own its morality. Bostrom responds that it's possible for an AI system to be highly intelligent without being motivated to act morally, explaining an early version of the orthogonality thesis[160], which states that an agent can have any combination of intelligence level and final goal.[161] Yudkowsky would reverse his opinion, devoting the rest of his career so far trying to reduce AI risks, and prevent AI-related catastrophe. | United States |

| 1999 | Weapons of mass destruction (biological weapon) | Literature | Ken Alibek and Stephen Handelman publish Biohazard: the Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World-Told from the Inside by the Man who Ran it.[162] | United States (Random House) |

| 1999 | Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider | Research | Arnon Dar publishes research on high energy physics experiments, and the possibility of relativistic heavy-ion colliders destroying the planet.[163][2] | Israel (Technion – Israel Institute of Technology) |

| 2000 | Pandemic | Organization | The Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network is established.[164] It provides international public health resources to control outbreaks and public health emergencies worldwide.[165] | |

| 2000 | Multiple | Research | Corey S. Powell and Diane Martindale publish an article describing 20 scenarios of how the world could end suddenly: asteroid impact, gamma ray burst, collapse of the vacuum, rogue black holes, giant solar flares, reversal of earth's magnetic field, flood-basalt volcanism, global warming, ecosystem collapse, biotech disaster, particle accelerator mishap, nanotechnology disaster, environmental toxins, robots take over, mass insanity, alien invasion, and divine intervention.[166] | United States (Discover Magazine) |

| 2000 | Particle Accelerator Mishap | Research | The director of the Brookhaven Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, prompted by the possibility that the experiments that physicists carry out in particle accelerators might pose an existential risk, commissions an official report, after concerns resurface with the construction of powerful accelerators such as CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.[25] | United States |

| 2000 | Artificial intelligence | Research | Bill Joy suggests that if AI systems rapidly become super-intelligent, they may take unforeseen actions or out-compete humanity.[167] | |

| 2000 | Pandemic | Sample case | The genome of the extinct influenza virus of 1918 (A virus subtype H1N1) is resurrected piece by piece from preserved human lung tissue.[25] | |

| 2000 | Artificial intelligence | American cognitive and computer scientist Marvin Minsky raises the subject of the Riemann Hypothesis Catastrophe, that an AI asked to solve the Riemann Hypothesis would convert the Solar System into computronium, a material hypothesized by Norman Margolus and Tommaso Toffoli of MIT in 1991 to be used as "programmable matter".[168] | ||

| 2000 | Artificial intelligence | Organization | The Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) is founded as the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence by Brian Atkins, Sabine Atkins and Eliezer Yudkowsky[169], with the purpose of accelerating the development of artificial intelligence.[170][171][172] After Yudkowsky begins to be concerned that AI systems developed in the future could become superintelligent and pose risks to humanity,[170], the institute would move in 2005 to Silicon Valley and begin to focus on ways to identify and manage those risks, which are at the time largely ignored by scientists in the field.[172] Today, MIRI is an independent non-governmental organizations (NGO), with the purpose to reduce the risk of a catastrophe caused by artificial intelligence.[173] | United States |

| 2001 (January 1) | Multiple | Eschatology | Graham Oppy publishes paper Physical Eschatology, in which he reviews evidence which strongly supports the claim that life will eventually be extinguished from the universe.[174] Occasionally the term "physical eschatology" is applied to the long-term predictions of astrophysics about the future of Earth and ultimate fate of the universe.[175][176] | Australia |

| 2001 (January) | Biotechnology | Sample case | A group of Australian researchers unintentionally change characteristics of the mousepox virus while trying to develop a virus to sterilize rodents, creating a virus that kills them by crippling their immune system.[177][178] The modified virus becomes highly lethal even in vaccinated and naturally resistant mice.[179] | Australia |

| 2001 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Organization | The Nuclear Threat Initiative is formed.[180] It is a nonprofit, nonpartisan global security organization focused on reducing nuclear and biological threats.[181] | |

| 2001 | Environmental disaster | Program launch | The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment is launched.[182] It is a four-year international scientific assessment of the condition of Earth's ecosystems, potential impacts of changes to ecosystems on their ability to meet human needs, and policies, technologies, and tools to improve ecosystem management.[183] | |

| 2001 | Environmental disaster | Sample case | 2 million trees are destroyed in Florida in an effort to contain a natural outbreak of Xanthomonas campestris, a bacterium that threatening the state's citrus industry and for which there is no cure. This event demonstrates that crops can be particularly vulnerable to an attack.[25] | United States |

| 2001 | Environmental disaster | Research | Analyses of the fossil record by Alroy et al. suggest that recovery to former diversity levels from even severe environmental disasters may be more rapid than had previously been thought.[25] | |

| 2001 (September–October) | Bioterrorism | Sample case | The 2001 anthrax attacks occur when anthrax spores through the mail cause 17 illnesses and 5 deaths in the United States in.[25] | United States |

| 2002 | Multiple | Concept development | Nick Bostrom publishes a seminal paper, which defines existential risk as "One where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential".[3] "we date the beginning of Existential Risk studies as a unified field of research to the 2002 paper Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards (Bostrom 2002) by Nick Bostrom"[2] | |

| 2002 | Weapons of mass destruction | Program launch | The G-8 Global Partnership arranges a target of 20 billion dollars to be committed over a 10-year period for the purpose of preventing terrorists from acquiring weapons and materials of mass destruction.[25] | |

| 2002 | Multiple | Organization | SpaceX is founded by Elon Musk, with the goal of reducing space transportation costs to enable the colonization of Mars.[184] | United States |

| 2002 | Artificial intelligence | Notable comment | According to philosopher Nick Bostrom, it is possible that the first super-intelligence to emerge would be able to bring about almost any possible outcome it valued, as well as to foil virtually any attempt to prevent it from achieving its objectives.[185] | |

| 2002 (October 7) | Impact event | Organization | B612 Foundation is founded[186] with the goal "to develop tools and technologies to understand, map, and navigate our solar system and protect our planet from asteroid impacts."[187] | United States |

| 2002 (December) | Nanotechnology | Organization | Mike Treder and Chris Phoenix found the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology.[188] | |

| 2003 | Multiple | Literature | British Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees publishes Our Final Hour.[189] A celebrated cosmologist, Rees offers a ‘scientist’s warning’ that humanity faces unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. Rees concludes that the probability of civilization surviving the next 100 years is perhaps 50%.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 2003 | Impact event | Budget | A NASA study of a follow-on program suggests spending US$250–450 million to detect 90% of all near-Earth asteroids 140 meters and larger by 2028.[190] | United States (NASA) |

| 2003 | Climate change | Sample case | The 2003 European heat wave results in seventy thousand deaths. While heatstroke is not the only risk from catastrophic climate change, it is among the most potent.[4] | Europe |

| 2004 | Multiple | Organization | The Global Risk Network is established,[191] by the World Economic Forum in an attempt to bring together cross-sectoral responses to a new set of emerging global risks.[192] | |

| 2004 | Pandemic | Sample case | SARS escapes from the National Institute of Virology in Beijing[26] when a graduate student develops symptoms just two weeks after she started working at the virology institute.[193] | China |

| 2004 | Weapons of mass destruction (biological weapon) | Literature | Luther E. Lindler, Frank J. Lebeda and George Korch publish Biological Weapons Defense: Infectious Disease and Counterbioterrorism, which provides an overview of the threat of biological weapons and the measures that could be taken to protect against them.[194] | |

| 2004 | Multiple | Literature | American economist Richard Posner publishes Catastrophe: Risk and Response,[195] which examines four risks whose worst cases could end advanced human civilization or worse: impact events, a catastrophic chain reaction initiated in high-energy particle accelerators, climate change, and bioterrorism.[196] | United States (Oxford University Press, USA) |

| 2005 | Multiple | Organization | The Future of Humanity Institute is founded.[197] Located at University of Oxford, it is a multidisciplinary research center enabling researchers to use mathematics, science, and philosophy to bear on big-picture questions about humanity and its prospects.[198] | United Kingdom (University of Oxford) |

| 2005 (March) | Impact event | Policy | The George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey Act. is introduced by Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA). Named in honor to United States Representative George Brown Jr. for his commitment to planetary defense, the bill has the purpose "to provide for a Near-Earth Object Survey program to detect, track, catalogue, and characterize certain near-Earth asteroids and comets".[199] | United States |

| 2005 | Pandemic | Literature | Jo Hays publishes Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, which details the devastating effects that major outbreaks have had on society throughout the ages. Hays argues that epidemics and pandemics are not simply medical problems, but also social and economic ones that can have a profound impact on a community.[200] | |

| 2005 | Technology | Literature | Jared Diamond publishes Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, in which the author first defines collapse: "a drastic decrease in human population size and/or political/economic/social complexity, over a considerable area, for an extended time." Diamond argues that history presents several examples of the phenomenon in which technologies that are desirable in themselves can get out of control, leading to catastrophic exhaustion of resources or accumulation of externalities. Examples range from small island cultures to major civilizations.[25][201] | United States (Viking Press) |

| 2005 | Pandemic | Research | According to Bonn, more than 150 countries do not have national strategies to deal with a possible influenza pandemic.[25] | |

| 2005 | Multiple | Organization | The Future of Humanity Institute is founded.[202] Based at the University of Oxford, it is a multidisciplinary research center applying mathematics, science, and philosophy to bear on big-picture questions about humanity and its prospects.[203] | United Kingdom |

| 2005 | Impact event | Program launch | The United States Congress again direct NASA to find at least 90 percent of potentially hazardous near-Earth objects sized 140 meters or larger by the end of 2020.[204] | United States (NASA) |

| 2005 (November) | Impact event | open letter | A number of astronauts publish an open letter through the Association of Space Explorers calling for a united push to develop strategies to protect Earth from the risk of a cosmic collision.[205] | |

| 2006 | Weapons of mass destruction (biological weapon) | Literature | Mark Wheelis, Lajos Rózsa and Malcolm Dando publish Deadly cultures: biological weapons since 1945, which investigates the use of biological weapons throughout history.[206] | United States (Harvard University Press) |

| 2006 | Impact event | Program launch | NEO Surveyor is first proposed[207] as a planned space-based infrared telescope designed to survey the Solar System for potentially hazardous asteroids.[208] A 50-centimeter-wide telescope, its camera sees things in infrared wavelengths, which reveal heat signatures. This is perfect for asteroids because they are very dark and hard to see against the blackness of space.[209] It is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[210] | United States (NASA) |

| 2006 (June 1) | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | The Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, chaired by Dr. Hans Blix, publishes Weapons of Terror: Freeing the World of Nuclear, Biological And Chemical Arms In this report, which presents 60 recommendations on what the world community can and should do to avoid nuclear war.[211] | United States |

| 2006 (June 19) | Multiple | Preservation | The prime ministers of Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland lay "the first stone" to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.[212] Located in the island of Spitsbergen the vault now has the capacity to hold 2.25 billion seeds, is intended to “provide insurance against both incremental and catastrophic loss of crop diversity.”[213] | Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Iceland |

| 2007 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Research | Members of the original group of nuclear winter scientists collectively perform a new comprehensive quantitative assessment utilizing the latest computer and climate models. They conclude that even a small-scale, regional nuclear war could kill as many people as died in all of World War II and seriously disrupt the global climate for a decade or more, harming nearly everyone on Earth.[25] | |

| 2007 | Artificial intelligence | Research | Eliezer Yudkowsky believes risks from artificial intelligence are harder to predict than any other known risks due to bias from anthropomorphism. Since people base their judgments of artificial intelligence on their own experience, he claims they underestimate the potential power of AI.[214] | United States |

| 2007 (November 8) | Impact event | Program launch | The House Committee on Science and Technology's Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics holds a hearing to examine the status of NASA's Near-Earth Object survey program. The prospect of using the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer is proposed by NASA officials.[215] | United States (NASA) |

| 2008 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | Michael Dobbs publishes One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War, which describes what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. called “the most dangerous moment in human history”.[216] | |

| 2008 | Nanotechnology | Research | According to Chris Phoenix and Mike Treder, molecular manufacturing could be used to cheaply produce, among many other products, highly advanced, durable weapons. Being equipped with compact computers and motors these could be increasingly autonomous and have a large range of capabilities. Phoenix and Treder classify catastrophic risks posed by nanotechnology into three categories:

|

|

| 2008 | Biotechnology | Research | According to Noun and Chyba, a biotechnology catastrophe may be caused by accidentally releasing a genetically engineered organism from controlled environments, by the planned release of such an organism which then turns out to have unforeseen and catastrophic interactions with essential natural or agro-ecosystems, or by intentional usage of biological agents in biological warfare or bioterrorism attacks. Noun and Chyba propose three categories of measures to reduce risks from biotechnology and natural pandemics: Regulation or prevention of potentially dangerous research, improved recognition of outbreaks, and developing facilities to mitigate disease outbreaks (e.g. better and/or more widely distributed vaccines).[218] | |

| 2008 | Artificial intelligence | Probability | A survey by the Future of Humanity Institute estimates a 5% probability of extinction by super-intelligence by 2100.[219] | United Kingdom (University of Oxford) |

| 2008 | Multiple | Concept developoment | Eliezer Yudkowsky introduces the Moore's Law of Mad Science, which states that "every 18 months, the minimum IQ necessary to destroy the world drops by one point".[220][221] | United States |

| 2008 | Biotechnology | Probability | A survey by the Future of Humanity Institute estimates a 2% probability of extinction from engineered pandemics by 2100.[219] | United Kingdom (University of Oxford) |

| 2008 | Multiple | Notable comment | U.S. economist Robin Hanson argues that a refuge permanently housing as few as 100 people would significantly improve the chances of human survival during a range of global catastrophes.[222] | United States |

| 2008 | Totalitarianism | Notable comment | American economist and author Bryan Caplan writes that "perhaps an eternity of totalitarianism would be worse than extinction". He states that it is better to risk extinction than to live under a dictatorship forever. Caplan also believes that the human capacity for suffering is so great that even the worst possible life would be preferable to an infinite amount of pain.[223] | United States |

| 2008 | Multiple | Literature | Nick Bostrom publishes Global Catastrophic Risks, which examines the possibility of disastrous events that could bring about the end of human civilization, or even lead to the extinction of the human race. Bostrom looks at a variety of risks, including those posed by nuclear war, climate change, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence.[25] | |

| 2009 | Impact event | Research | Research published in an issue of the journal Nature, describes how scientists were able to identify an asteroid in space before it entered Earth's atmosphere, enabling computers to determine its area of origin in the Solar System as well as predict the arrival time and location on Earth of its shattered surviving parts. The four-meter-diameter asteroid, called 2008 TC3, was initially sighted by the automated Catalina Sky Survey telescope, on October 6, 2008. Computations correctly predict that it would impact 19 hours after discovery and in the Nubian Desert of northern Sudan.[224] | United Kingdom (Nature Research) |

| 2009 | Artificial intelligence | Research | The Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) hosts a conference to discuss the possibility of computers and robots acquiring autonomy, and the potential risks associated with this. They note that some robots have already acquired various forms of semi-autonomy, including the ability to find power sources on their own and to independently choose targets to attack with weapons. They also note that some computer viruses can evade elimination and have achieved "cockroach intelligence". The researchers note that self-awareness is probably unlikely, but there are other potential hazards and pitfalls.[225] | United States (Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence) |

| 2009 | Pandemic | Literature | Alan Sipress publishes The Fatal Strain: On the Trail of Avian Flu and the Coming Pandemic.[226] | United States (Penguin Publishing Group) |

| 2009 | Pandemic | Program launch | The Emerging Pandemic Threats program is launched[227] with the purpose to strengthen global capacity for detection of viruses with pandemic potential that can move between animals and people.[228] | |

| 2009 | Multiple | Concept development | M. L. Weitzman presents his 'dismal theorem', which states that a standard cost-benefit analysis may break down if there is a possibility of catastrophes occurring.[229] The “dismal” theorem tells that it is an error to use trade-off analysis under existential risk.[230] | |

| 2010 | Multiple | Literature | Robert Wuthnow publishes Be Very Afraid: The Cultural Response to Terror, Pandemics, Environmental Devastation, Nuclear Annihilation, and Other Threats.[231] | United States (Oxford University Press, USA) |

| 2010 | Weapons of mass destruction (chemical weapon, niological weapon) | Literature | Edward M. Spiers publishes A history of chemical and biological weapons, which attempts to provide a detailed history of the use of chemical and biological agents in warfare.[232] | |

| 2011 | Multiple | Organization | The Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere (MAHB) is formed[233] at Stanford University, with the purpose to gather organizations concerned about the existential threats to civilization.[234] MAHB is a meeting place for citizens concerned with the interconnections among the greatest threats to human well being.[235] | United States |

| 2011 | Impact event | Research | Dr. Bong Wie at Asteroid Deflection Research Center at Iowa State University, after studying strategies that could deal with 50-to-500-metre-diameter objects when the time to Earth impact is less than one year, concludes that to provide the required energy, a nuclear explosion or other event that could deliver the same power, are the only methods that can work against a very large asteroid within these time constraints.[236] | United States (Iowa State University) |

| 2011 | Biotechnology, pandemic | Sample case | Dutch virologist Ron Fouchier of the Erasmus University Medical Center engineers a deadly, airborne version of the H5N1 influenza virus.[237] The virus is believed to kill 60 percent of the people it infects.[238] | Netherlands (Erasmus University Medical Center) |

| 2011 | Pandemic | Literature | Nathan Wolfe publishes The Viral Storm: The Dawn of a New Pandemic Age, which explores the dangers of pandemics in the modern world.[239] | United States (Henry Holt and Company) |

| 2011 | Multiple | Organization | The Global Catastrophic Risk Institute (GCRI) is founded by Seth Baum and Tony Barrett.[240] It is a think tank that analyzes the risk of catastrophes severe enough to threaten the survival of human civilization.[241] | United States (Washington, DC.) |

| 2012 (January) | Impact event | Literature | After a near pass-by of object 2012 BX34, a paper entitled A Global Approach to Near-Earth Object Impact Threat Mitigation is released by an international team of researchers. The paper discusses the "NEOShield" project.[242] | Russia, Germany, United States, France, Britain, Spain |

| 2012 (February 23) | Impact event | Research | The small asteroid 367943 Duende is discovered and successfully predicted to be on close but non-colliding approach to Earth again just 11 months later.[243] Due to its tiny size and having been closely monitored, this discovery is considered a landmark prediction. | |

| 2012 | Multiple | Organization | The Centre for the Study of Existential Risk is founded.[244] A research center located at the University of Cambridge, it is dedicated to the study and mitigation of existential risks that could lead to human extinction or irrevocable civilisational decline.[245] | United Kingdom (University of Cambridge) |

| 2012 (June) | Pandemic | Sample case | With the purpose to study human adaptation, researchers publish the creation of highly lethal and virulent artificial strains of H5N1.[246] | |

| 2011 (August) | Giant Solar Flares | Conference | Nasa holds a press conference about Solar Flares and their effects on the Earth. Solar flares are a type of energy release that can cause disruptions on the Earth, including power outages and interference with communications.[247] | United States (NASA) |

| 2012 | Impact event | Research | V.P. Vasylyev proposes to apply the ring-array concentrator as an alternative design of a mirrored collector for deflecting hazardous near-earth objects.[248] This type of collector has an underside lens-like position of its focal area that avoids shadowing of the collector by the target and minimizes the risk of its coating by ejected debris. | |

| 2012 | Multiple | Organization | The Global Challenges Foundation is founded by the Swedish financial analyst and author Laszlo Szombatfalvy.[249] It aims to "incite deeper understanding of the most pressing threats to humanity - and to catalyse new ways of tackling them".[250] | Sweden |

| 2012 | Weapons of mass destruction (nuclear weapon) | Literature | M.A. Harwell publishes Nuclear Winter: The Human and Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War, which argues that comparatively little scientific research has been done about the envifonmental consequences of a nuclear war of the magnitude of the arsenal at the time could unleash.[251] | |