Timeline of healthcare in China

This is a timeline of healthcare in China, focusing especially on modern science-based medicine healthcare. Major events such as crises, policies and organizations are included.

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 2500BP-1949 | Traditional Chinese Medicine prevails in this time which covers most of the history of China. Chinese herbology, acupuncture, dietary therapy, tai chi, tui na and qigong thrive.[1] Around the 19th century, western-inspired evidence-based medicine makes its way into the country. |

| 1949–1980 | With modern medicine already established, after the Communist Party takes over in 1949, healthcare is nationalized. A national "patriotic health campaign" is attempted to address basic health and hygiene education, and basic primary care is dispatched to rural areas through barefoot doctors and other state-sponsored programs. During this period, Infant mortality falls from 200 to 34 per 1000 live births, and life expectancy increases from about 35 to 68 years.[2] |

| 1978–present | Period of economic liberalization. The rural cooperative medical system disintegrates and the barefoot doctors program comes to an end. The increase in the elderly population and their lack of health insurance and pensions will also place enormous pressure on services for their care. All these changes have great impact on the rural health care system, leaving the urban system basically intact, and contribute to the rural-urban disparity in health care. Period of one-child policy.[3] |

Full timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11th Century BC – 771 BC | Organization | In the Western Zhou dynasty, imperial doctors are divided into four departments: Dietetic (food and beverage hygiene); Diseases (internal medicine); Sores (external medicine); and Veterinary.[4] | |

| 770 BCE – AD 221 | Compilation | Medical researchers compile the written records and oral knowledge of Chinese medicine from the previous ages and write the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. This book systematizes and consolidates ancient medical experience and theory into one compendium.[4] | |

| 265 AD – 907 AD | Development | During the Jin and Tang dynasties, Chinese medicine experiences great development. In the study of the origins of disease, diagnosis, pharmacology, specialization, medical training, and other aspects, great achievements are made.[4] | |

| 960 AD – 1368 AD | Development | During the Song and Yuan periods, due to the invention of printing technology and further advances in paper making, large quantities of Chinese medical texts are printed and published. This causes Chinese medicine to spread, giving rise to widespread and deep research.[4] | |

| 1700s | Development | The earliest contemporary hospitals begin to appear in China in the form of missionary hospitals run by western churches.[5] | |

| 1844 | Organization (hospital) | Renji Hospital is founded.[6][7] | Shanghai |

| 1876–1879 | Crisis | Northern Chinese Famine kills an estimated 13 million people.[8] | Shaanxi, Hebei, Henan, Shandong and Jiangsu. |

| 1883 | Organization (hospital) | Sheng Jing Hospital is established.[9] | Shenyang |

| 1894 | Organization (medical school) | Hebei Medical University is established.[10][11] | Shijiazhuang |

| 1901 | Organization (hospital) | Haikou City People's Hospital is founded.[12] | Haikou |

| 1905 | Policy | The central government establishes a Sanitary Department.[13] | |

| 1907 | Organization (hospital) | Ruijin Hospital is founded.[14][15] | Shanghai |

| 1907 | Organization (medical school) | Tongji Medical College is established.[16] | Wuhan |

| 1908 | Organization (medical school) | Kung Yee Medical School and Hospital is established.[17] | Guangzhou |

| 1912 | Organization (medical school) | Wenzhou Medical College is established.[18] | Wenzhou |

| 1912 | Organization (medical school) | Zhejiang University School of Medicine is established.[19][20][21] | Hangzhou |

| 1912 | Organization (medical school) | Peking University Health Science Center is established.[22] | Beijing |

| 1912 | Organization (medical school) | Suzhou Medical College is established.[23][24] | Suzhou |

| 1917 | Organization (medical school) | Peking Union Medical College is established.[25][26] | Beijing |

| 1919 | Organization (medical school) | Shanxi Medical University is established.[27] | Shanxi |

| 1921 | Organization (medical school) | Xiamen University is established.[28][29][30] | Xiamen |

| 1921 | Organization (medical school) | Medical College of Nanchang University is established.[31][32] | Nanchang |

| 1927 | Organization (medical school) | Fudan University Shanghai Medical College is established.[33][34] | Shanghai |

| 1928–1930 | Crisis | Famine kills about 3 million people.[35] | Henan, Shaanxi, and Gansu |

| 1930-1939 | Development | The Rural Reconstruction Movement pioneers village health workers trained in basic health as a part of a coordinated system of rural uplift programs in the areas of health, education, employment etc.[36] | |

| 1933 | Organization (medical school) | Kunming Medical University is established.[37] | Kunming |

| 1934 | Organization (medical school) | Nanjing Medical University is established.[38][39] | Zhenjiang |

| 1935 | Organization (hospital) | Shanghai Mental Health Center is founded.[40] | Shanghai |

| 1937 | Organization (medical school) | Fujian Medical University is founded.[41][42] | Fuzhou |

| 1937 | Organization (hospital) | Shanghai Children's Hospital is founded.[43][44] | Shanghai |

| 1941 | Organization (medical school) | Fourth Military Medical University is established.[45][46] | Xi'an |

| 1942–1943 | Crisis | Famine kills 2 to 3 million people.[47] | Henan |

| 1945 | Organization (medical school) | Chengde Medical College is founded.[48][49] | Hebei |

| 1946 | Organization (medical school) | Changzhi Medical College is established.[50] | Changzhi |

| 1946 | Organization (medical school) | Liaoning Medical University is established.[51] | Jinzhou |

| 1947 | Organization (medical school) | Chengdu Medical College is established.[52] | Chengdu |

| 1947 | Organization (medical school) | Dalian Medical University is founded.[53] | Dalian |

| 1949 | Background | Inauguration of the People’s Republic of China. At this time the country has 40,000 doctors to care for a population of nearly 540 million. Despite a low urbanization rate, most physicians are concentrated in cities.[54] | |

| 1949 | Organization (hospital) | Tianjin First Central Hospital is founded.[55][56] | Tianjin |

| 1950-1959 | Campaign | Period of the Patriotic Health Campaigns.[57] | |

| 1951 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Guangzhou Pharmaceuticals is founded as a pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution company.[58] | Guangzhou |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | Tianjin Medical University is established. It is the first medical institution approved by the State Council of the People's Republic of China.[59][60] | Tianjin |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | Southwest Medical University is established.[61][62] | luzhou |

| 1951 | Organization (hospital) | Women's Hospital, Zhejiang University is founded.[63] | |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | Weifang Medical University is established.[64] | Weifang |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | Southern Medical University is established.[65][66] | Guangzhou |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | Sichuan Medical University is established.[67] | Luzhou |

| 1951 | Organization (medical school) | North Sichuan Medical University is established.[68][69] | Nanchong |

| 1953 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | North China Pharmaceutical Group Corp is founded.[70] | |

| 1954 | Organization | The Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China (MOH) is established.[71] | |

| 1956 | Organization (medical school) | Xinjiang Medical University is established.[72] | Xinjiang |

| 1956 | Organization (medical school) | Beijing University of Chinese Medicine is founded.[73] | Beijing |

| 1956 | Organization (medical school) | Chongqing Medical University is founded.[74][75] | Chongqing |

| 1956 | Crisis | An outbreak of the Influenza A virus subtype H2N2 occurs.[76] | Guizhou |

| 1957 | Organization (hospital) | Shanghai Chest Hospital is founded.[77] | Shanghai |

| 1957 | Report | There are over 200,000 village doctors across the nation, enabling farmers to receive basic health care at home and work every day.[78] | |

| 1958 | Organization (medical school) | Bengbu Medical College is founded.[79] | Bengbu |

| 1958 | Organization (medical school) | Ningxia Medical University is founded.[80][81] | Yinchuan |

| 1958 | Organization (medical school) | Wannan Medical College is established.[82] | Wuhu |

| 1958 | Campaign | The Four Pests Campaign is initiated by Mao Zedong, who identifies the need to exterminate mosquitoes, flies, rats, and sparrows.[83] | |

| 1958 | Organization (hospital) | Xinhua Hospital is founded.[84][85] | Shanghai |

| 1958–1959 | Campaign | The massive Great Leap Forward campaign is set to rapidly transform China into a modern communist society.[13] | |

| 1959–1961 | Crisis | The Great Chinese Famine leads to from about 15 million excess deaths (government statistics) to 30 million (scholarly estimates)[86] It is widely considered to be the direct consequence of the Great Leap Forward. | |

| 1960 | Organization (medical school) | Capital University of Medical Sciences is founded.[87] | Beijing |

| 1965 | Mao Zedong's speech on health care mentions the concept of "barefoot doctor".[36] | ||

| 1965 | Organization (medical school) | Hubei University of Medicine is established.[88] | Shiyan |

| 1967 | Campaign | The Project 523 is launched with the purpose of finding new drugs for malaria, a disease claiming many lives at the time. More than 500 Chinese scientists recruited. Artemisinin is discovered. Officially terminated in 1981.[89] | |

| 1968 | Policy | The barefoot doctors (farmers who receive minimal basic medical and paramedical training) program becomes integrated into national policy. In areas lacking medicine or urban-trained doctors, village doctors can go through short-term training – three months, six months, a year – before returning to their villages to farm and practise medicine.[78][90] | |

| 1970 | Organization (medical school) | Binzhou Medical College is established.[91] | Binzhou |

| 1971 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Yangtze River Pharmaceutical Group is founded.[92] | Taizhou |

| 1976 | Background | Mao Zedong dies.[93] | |

| 1978 | Background | The Communist Deng Xiaoping becomes paramount leader of China, giving birth to a new era of reforms.[94] | |

| 1979 | Organization (medical school) | Clinical Medicine College of Hangzhou Normal University is founded.[95] | Hangzhou |

| 1980 | Policy | One-child policy is introduced as a part of the family planning policy.[96] | |

| 1980–1989 | Study | The China–Cornell–Oxford Project is conducted to examine the diets, lifestyle, and disease characteristics of 6,500 people.[97] | 65 rural counties |

| 1981 | Organization | The National Family Planning Commission is formed. Dissolved in 2003.[98] | |

| 1984 | Reform | The government starts to implement free-market reforms. Free medical care is abolished.[99] | |

| 1985 | Policy | The Ministry of Health officially cancels the title of barefoot doctor.[13] Those able to pass qualifying examinations are now termed “rural doctors”, while others are re-categorized as health workers or medical aides.[54] | |

| 1985 | Organization | China’s State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SATCM) is established.[100] | |

| 1989 | Project | The China Health and Nutrition Survey is started.[101] | |

| 1989 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | CSPC Zhongrun is founded as a pharmaceutical manufacturer.[102][103] | |

| 1989 | Organization (medical school) | Changsha Medical University is founded.[104] | Changsha |

| 1993 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Jilin Aodong Medicine is established as a state-owned enterprise that manufactures patent drugs and pharmaceutical packaging products.[105] | Dunhua |

| 1994 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Tasly is founded. Notably producer of traditional Chinese medicines.[106][107] | Tianjin |

| 1995 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Tiens Group is founded.[108] | Tianjin |

| 1995 | Organization (Healthcare provider) | Shenzhen Goldway Industrial is founded as a manufacturer of medical devices.[109] | Shenzhen |

| 1995 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | China Nepstar is founded as a drugstore chain.[110][111] | Shenzhen |

| 1997 | Background | Deng Xiaoping dies.[112] | |

| 1998 | Policy | Health insurance becomes available for working urban residents through the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) program, which covers employees in private and state-owned enterprises, government, social organizations, and non-profits.[54] | |

| 1998 | Organization (hospital) | Shanghai Children's Medical Center is founded.[113] | Shanghai |

| 1999 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Haifu is established as a manufacturer of non-invasive ultrasound therapeutic systems for tumors.[114][115] | Chongqing |

| 2000 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Guizhentang Pharmaceutical company is founded as a company that profits from extracting bile out of Bile bears to make traditional Chinese medicine.[116] | Quanzhou |

| 2000 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | WuXi PharmaTech is founded.[117][118] | Shanghai |

| 2000 | Organization (healthcare provider) | Zhuhai Fornia Medical Device Company is founded as a Chinese-American joint venture that manufactures medical devices.[119][120] | Zhuhai |

| 2000 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Sinovac Biotech is founded as a manufacturer of vaccines against human infectious diseases.[121][122] | Beijing |

| 2002 | Policy | The system of Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is established by the Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine, creating a nationwide infrastructure for disease control and prevention.[13] | |

| 2002–2003 | Crisis | The Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic outbreaks in China.[123] | Guangdong Province |

| 2003 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | China National Pharmaceutical Group is founded. It is the largest pharmaceutical company in China.[124] | Beijing |

| 2003 | Organization (pharmaceutical company) | Nanjing Ange Pharmaceutical is founded as a drug manufacturer.[125] | Nanjing |

| 2003 | Organization | The National Population and Family Planning Commission (NPFPC) supersedes the National Family Planning Commission. Dissolved in 2013.[126] | |

| 2005 | Organization (hospital) | Beijing New Century International Hospital for Children is founded.[127] | Beijing |

| 2007 | Organization | Zhejiang Xinhua Compassion Education Foundation is founded as an NGO to address malnourished children in rural China.[128] | |

| 2007 | Execution | Zheng Xiaoyu, the former head of the State Food and Drug Administration, is executed for corruption.[129] | |

| 2008 | Crisis | Chinese milk scandal: It involves milk and infant formula along with other food materials and components being adulterated with melamine. An estimated 300,000 victims reported.[130] Six infants die from kidney stones and other kidney damage with an estimated 54,000 babies being hospitalized.[131][132] | |

| 2010 | Study | The Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS) is launched in 2010 by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University.[133] | |

| 2011 | Study | The The Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is conducted in order to examine health and economic adjustments to rapid ageing of the population in China.[134] | |

| 2011 | Report | Medical and healthcare institutions around the country number 954,000, licensed doctors (assistants) reach 2,466,000, or 1.8 per thousand people, registered nurses total 2,244,000, or 1.7 per thousand people, hospital beds reach 5,160,000, or 3.8 per thousand people.[135] | |

| 2012 | Achievement | Health insurance reaches 95 percent of the Chinese population.[99] | |

| 2013 | Organization | The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China (NHFPC) supersedes the NPFPC.[136] | Beijing |

| 2015 | Policy | The Chinese news agency Xinhua announces plans of the government to abolish the one-child policy, now allowing all families to have two children.[137] | |

| 2019 | Crisis | The first known case of COVID-19 is identified in Wuhan in December 2019.[138] The disease would since spread worldwide, leading to the COVID-19 pandemic.[139] | Wuhan |

Numerical and visual data

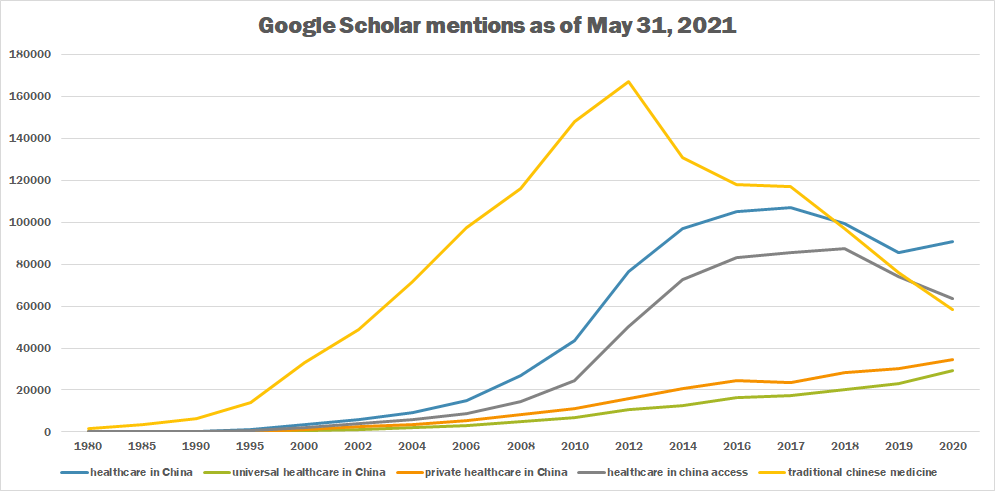

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 31, 2021.

| Year | healthcare in China | universal healthcare in China | private healthcare in China | healthcare in china access | traditional chinese medicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 89 | 32 | 40 | 47 | 1,820 |

| 1985 | 91 | 15 | 36 | 51 | 3,430 |

| 1990 | 250 | 55 | 117 | 136 | 6,620 |

| 1995 | 1,050 | 194 | 325 | 486 | 14,200 |

| 2000 | 3,350 | 780 | 1,370 | 2,160 | 32,900 |

| 2002 | 5,780 | 1,310 | 2,520 | 3,790 | 48,900 |

| 2004 | 9,470 | 2,020 | 3,730 | 5,760 | 71,700 |

| 2006 | 14,900 | 3,180 | 5,580 | 9,020 | 97,600 |

| 2008 | 26,700 | 4,900 | 8,140 | 14,660 | 116,000 |

| 2010 | 43,500 | 6,860 | 11,300 | 24,500 | 148,000 |

| 2012 | 76,500 | 10,500 | 16,100 | 50,400 | 167,000 |

| 2014 | 97,100 | 12,600 | 20,700 | 72,500 | 131,000 |

| 2016 | 105,000 | 16,200 | 24,400 | 83,100 | 118,000 |

| 2017 | 107,000 | 17,600 | 23,400 | 85,700 | 117,000 |

| 2018 | 99,200 | 20,200 | 28,300 | 87,700 | 96,800 |

| 2019 | 85,500 | 23,000 | 30,200 | 74,200 | 75,800 |

| 2020 | 90,900 | 29,100 | 34,300 | 63,600 | 58,400 |

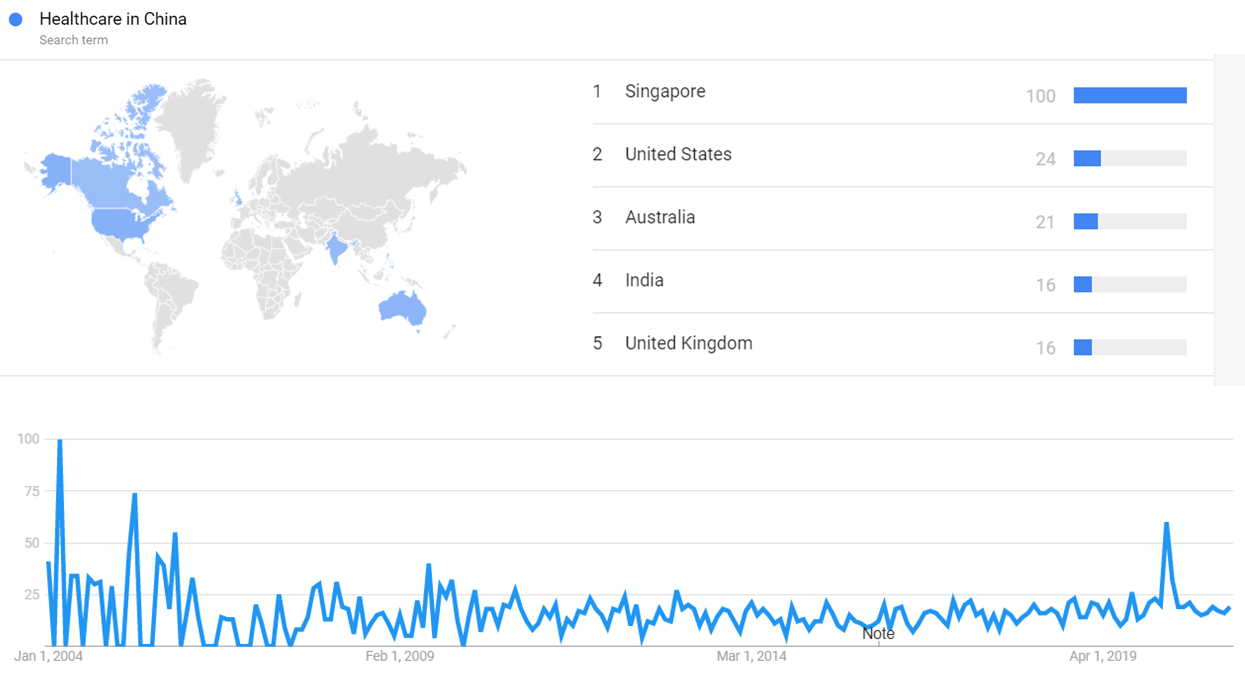

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data for Healthcare in China (Search term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[140]

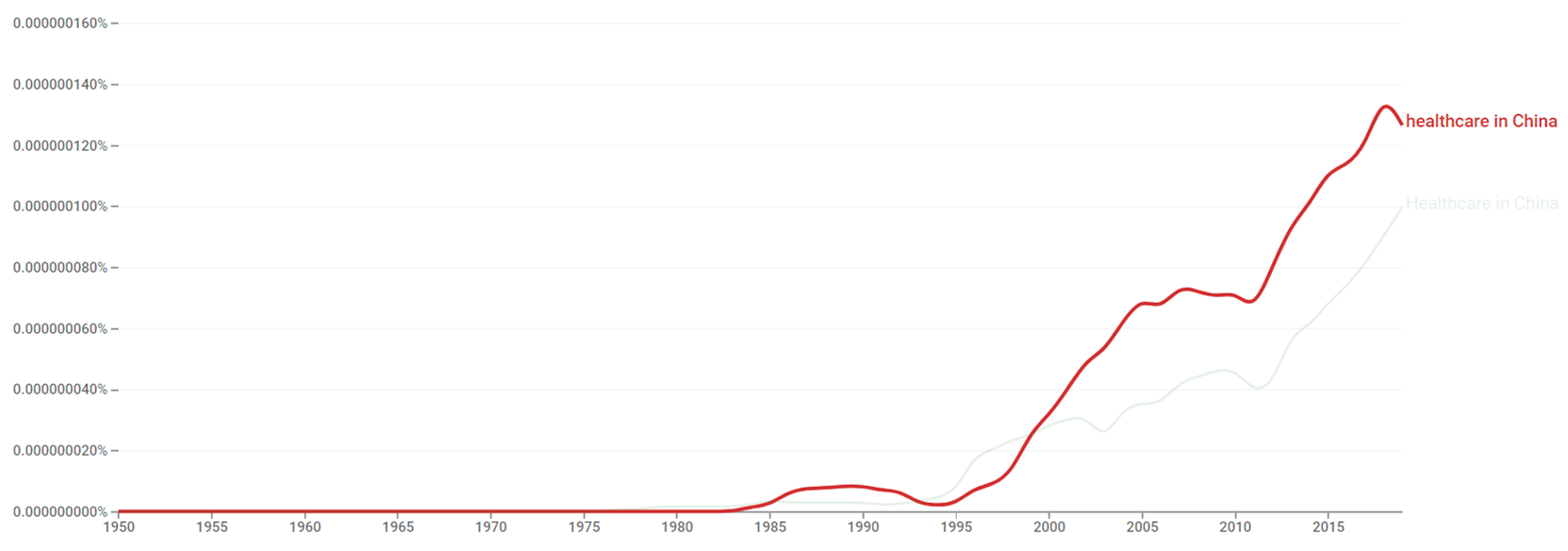

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Healthcare in China from 1950 to 2019.[141]

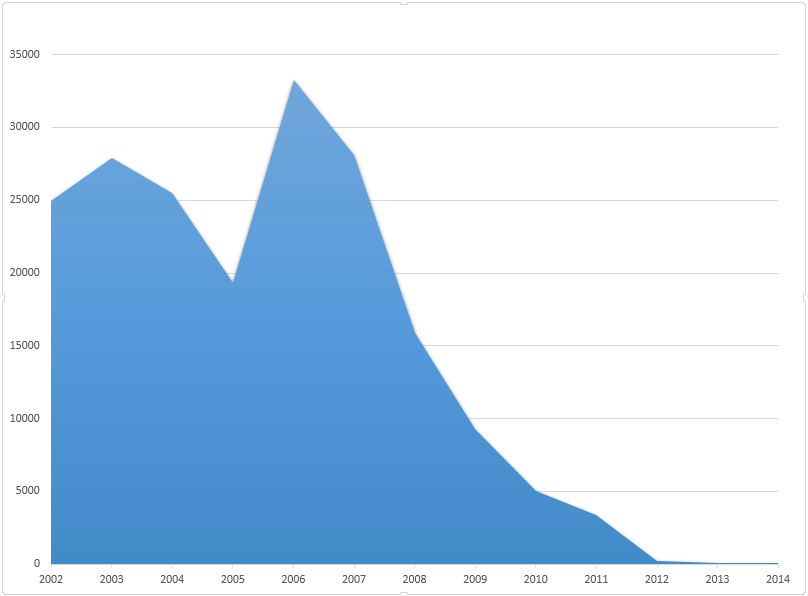

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Healthcare in China, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.[142]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

- Healthcare in China

- Health in China

- [[Timeline of universal healthcare}}

- Timeline of healthcare in India

- Timeline of healthcare in Japan

External links

References

- ↑ Traditional Chinese Medicine, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Introduction

- ↑ Winnie Yipa; William C. Hsiaob (25 Feb 2015). "What Drove the Cycles of Chinese Health System Reforms". Health Systems & Reform. 1: 52–61. doi:10.4161/23288604.2014.995005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ↑ Shi L (1993). "Health care in China: a rural-urban comparison after the socioeconomic reforms". Bull. World Health Organ. 71. PubMed: 723–36. PMC 2393531. PMID 8313490..

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Historical Timeline of Chinese Medicine".

- ↑ "Historical Evolution of Chinese Healthcare System".

- ↑ "About Renji". renji.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Renji Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine". chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Epidemic Chinese Famine". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Josai Visits China Medical University". josai.jp. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Hebei Medical University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Hebei Medical University". chinaeducenter.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Haikou City People's Hospital". tophealthclinics.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Public Health Education in India and China" (PDF).

- ↑ "Ruijin Hospital". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Ruijin Hospital". smartshanghai.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Tongji Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Kung Yee Medical School and Hospital". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Wenzhou Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Zhejiang University School of Medicine". cmm.zju.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Zhejiang University School of Medicine". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Zhejiang University". chinaeducenter.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Peking University Health Science Center". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Overview - School of Biology & Basic Medical Sciences Soochow". suda.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Suzhou Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Macy, Josiah (1972). Western medicine in a Chinese palace: Peking Union Medical College, 1917-1951. Jr. Foundation. p. 250. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Peking Union Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Shanxi Medical University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Xiamen University". xmu.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Xiamen University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Xiamen University". topuniversities.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Nanchang University". qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Medical College of Nanchang University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Fudan University Shanghai Medical College". besteduchina.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fudan University Shanghai Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Through Chinese eyes: tradition, revolution, and transformation by E. Vernoff and P. J. Seybolt.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Chinese cooperation in health sector".

- ↑ "Kunming Medical University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Nanjing Medical University". njmu.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Nanjing Medical University International New Students Scholarship". csc.edu.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Shanghai Mental Health Center". sinoaid.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Introduction to FJMU". fjmu.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fujian Medical University". csc.edu.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Shanghai Children's Hospital". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "A Two-Way Street to China". uchicagokidshospital.org. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fourth Military Medical University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Fourth Military Medical University (FMMU)". www.natureindex.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Micah S. Muscolino (2011). 'Violence against people and the land: The environment and refugee migration from China's Henan Province, 1938–1945.' Environment and History (17), pp. 301–302.

- ↑ "Chengde Medical College". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Chengde Medical College". university-directory.eu. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Changzhi Medical College". epoch-abroad.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Liaoning Medical University". china-admissions.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Chengdu Medical College". haltenraum.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "DLM Highlights". cucas.edu.cn. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Arthur Daemmrich (2013). "The political economy of healthcare reform in China: negotiating public and private". Springerplus. 2: 448. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-448. PMC 3776089. PMID 24052932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ "Tianjin First Center Hospital". tj-fch.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ↑ "Investigative Report: A Hospital Built for Murder". theepochtimes.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Critical health literacy: a case study from China in schistosomiasis control".

- ↑ "Company Overview of Guangzhou Pharmaceuticals Corporation". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Tianjin Medical University". tijmu.edu.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Tianjin Medical University". healthsciencessc.org. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Luzhou Medical College (Southwest Medical University)". sicas.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Southwest University". csc.edu.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Women's Hospital, Zhejiang University". morebooks.de. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Weifang Medical University". cucas.edu.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Southern Medical University". smu.edu.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "STMU Highlights". school.cucas.edu. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "North Sichuan Medical University MBBS Program". chinaeducenter.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "川北医学院历史沿革". nsmc.edu.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "North Sichuan Medical University". chinaeducenter.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ China Medical and Pharmaceutical Industry Handbook Volume.1 Strategic ... IBP USA. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "中華人民共和國國家衛生和計劃生育委員會". chinalawinfo.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Xinjiang Medical University". universityscholarship4china.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ 北京中医药大学校志: 1956年-1992年. 学苑出版社. 2002. p. 740. ISBN 7800601943. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Chongqing". cqmu.edu.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "CQMU Highlights". school.cucas.edu.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Connie. [2007] (2007) Influenza: The Next Pandemic? 21st century publishing. ISBN 0-7613-9457-5

- ↑ "Shanghai Chest Hospital". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "China's village doctors take great strides".

- ↑ "蚌埠医学院". people.com.cn. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Ningxia Medical University". ningxiamedical.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ www.csc.edu.cn http://www.csc.edu.cn/studyinchina/universitydetailen.aspx?collegeId=295. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Wannan Medical College". 4icu.org. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ Shapiro, Judith Rae (2001). Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78680-0.

- ↑ "Xinhua Hospital". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University". chinaorganharvest.org. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Holmes, Leslie. Communism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-955154-5. p. 32 "Most estimates of the number of Chinese dead are in the range of 15 to 30 million."

- ↑ "学校简介". myuall.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "湖北医学院". chinashuijing.com. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ Weiyuan, C (2009). "Ancient Chinese anti-fever cure becomes panacea for malaria". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 87 (10): 743–744. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.051009. PMC 2755319. PMID 19876540.

- ↑ Zhang, Daqing; Paul U. Unschuld (2008). "China's barefoot doctor: Past, present, and future". The Lancet. 372 (9653): 1865–1867. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61355-0. PMID 18930539.

- ↑ "BINZHOU MEDICAL UNIVERSITY (MBBS)". studyabroad.page4.me. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ↑ "Company Overview of Jiangsu Yangtze River Pharmaceutical Group Company Ltd". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Mao biography".

- ↑ "Deng Xiaoping".

- ↑ "Clinical Medicine College of Hangzhou Normal University". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "Family Planning in China".

- ↑ "China-Cornell-Oxford Project", Cornell University.

- "Geographic study of mortality, biochemistry, diet and lifestyle in rural China", Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit, University of Oxford, accessed February 3, 2011.

- ↑ Hemminki, Elina; Cao, Guiying; Viisainen, Kirsi; Wu, Zhuochun (2005). "Illegal births and legal abortions – the case of China". Reproductive Health. 2: 5. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-2-5. PMC 1215519. PMID 16095526. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 99.0 99.1 "What China Can Teach The World About Successful Health Care".

- ↑ Qihe XuEmail, Rudolf Bauer, Bruce M Hendry, Tai-Ping Fan, Zhongzhen Zhao, Pierre Duez, Monique SJ Simmonds, Claudia M Witt, Aiping Lu, Nicola Robinson, De-an Guo and Peter J Hylands (13 June 2013). "The quest for modernisation of traditional Chinese medicine". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 13. BioMed Central: 132. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-13-132. PMC 3689083. PMID 23763836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF, Popkin BM (2014). "The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989-2011". Obes Rev. 15 Suppl 1. PubMed: 2–7. doi:10.1111/obr.12119. PMC 3869031. PMID 24341753.

- ↑ "Company background of CSPC Hebei Zhongrun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd". cnchemicals.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Hebei Zhongrun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (CSPC Zhongrun) - See more at: http://www.companiess.com/hebei_zhongrun_pharmaceutical_co_ltd_cspc_zhongrun_info1808943.html#sthash.TWbRSfN9.dpuf". companiess.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ↑ "CHANGSHA MEDICAL UNIVERSITY". admissions.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Porter, Valerie; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen J.G.; Sponenberg, D. Phillip. Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding, 2 Volume Pack. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Tasly". Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "Tasly Pharmaceutical Group Co Ltd". reuters.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Company Overview of Tiens Group Co., Ltd". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Shenzhen Goldway Industrial". Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "About Us". nepstar.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "China Nepstar Chain Drugstore Ltd". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Deng Xiaoping biography".

- ↑ "Shanghai Children's Medical Center". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "About Haifu". haifumedical.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Chongqing Haifu expands international market". thechinatimes.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Ricard, Matthieu. A Plea for the Animals: The Moral, Philosophical, and Evolutionary ... Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Us". wuxiapptec.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Company Overview of WuXi PharmaTech (Cayman) Inc". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Zhuhai Fornia Medical Device Company". Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "ZHUHAI FORNIA MEDICAL DEVICE COMPANY". economictimes.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Sinovac". sinovac.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Sinovac Biotech Ltd". scrip.pharmamedtechbi.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Smith, R. D. (2006). "Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks, Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management". Social Science and Medicine. 63 (12): 3113–3123. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. PMID 16978751.

- ↑ "Company Overview of China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Nanjing Ange Pharmaceutical". Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "National Population and Family Planning Commission".

- ↑ "Beijing Childrens Hospital". omicsonline.org. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Zhejiang Xinhua Compassion Education Foundation".

- ↑ "China Ex-Food and Drug Chief Executed".

- ↑ Branigan, Tania (2 December 2008). "Chinese figures show fivefold rise in babies sick from contaminated milk". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Scott McDonald (22 September 2008). "Nearly 53,000 Chinese children sick from milk". Google. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014.

- ↑ Jane Macartney (22 September 2008). "China baby milk scandal spreads as sick toll rises to 13,000". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "China Family Panel Studies".

- ↑ Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G (2014). "Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS)". Int J Epidemiol. 43. PubMed: 61–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dys203. PMC 3937970. PMID 23243115.

- ↑ "Medical and Health Services in China".

- ↑ "NHFPC".

- ↑ "China to end one-child policy and allow two".

- ↑ Page J, Hinshaw D, McKay B (26 February 2021). "In Hunt for Covid-19 Origin, Patient Zero Points to Second Wuhan Market – The man with the first confirmed infection of the new coronavirus told the WHO team that his parents had shopped there". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ Zimmer C (26 February 2021). "The Secret Life of a Coronavirus – An oily, 100-nanometer-wide bubble of genes has killed more than two million people and reshaped the world. Scientists don't quite know what to make of it". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ↑ "Healthcare in China". Google Trends. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "Healthcare in China". books.google.com. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "Healthcare in China". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "China statistics summary (2002 - present)". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

Template:Health in the People's Republic of China Template:China topics Template:Asia topic Template:Public health