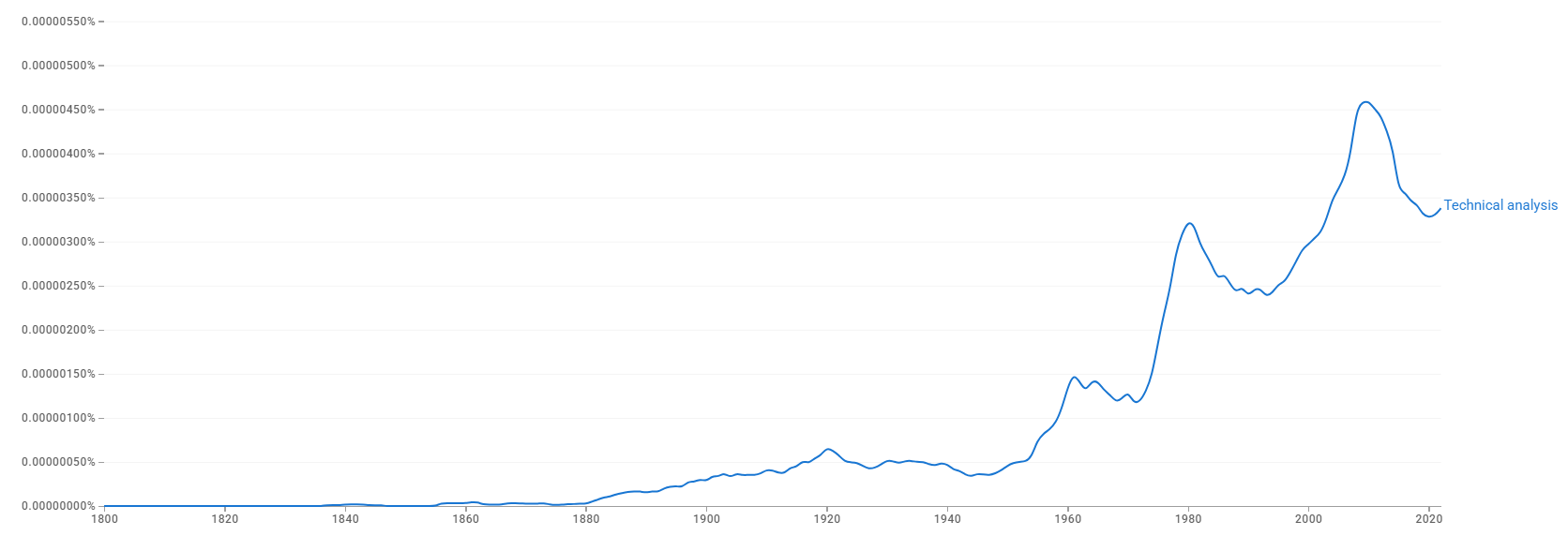

Timeline of technical analysis

This is a timeline of technical analysis, a method used to evaluate and predict price movements in financial markets by analyzing historical price charts, trading volume, and patterns. Technical analysis focuses on market trends and investor behavior, rather than a company’s fundamentals, using tools like moving averages, support and resistance levels, and technical indicators.

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What are some major stages of market growth across history?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Market development".

- You’ll see a chronological overview of how markets expanded and transformed, from early barter in the Jordan Valley to Mesopotamian trade systems, the invention of coinage, Roman commerce, Japanese rice exchanges, and New York’s first formal market. Each stage illustrates key moments of market growth shaping global economic history.

- What important software and platforms emerged in the development of technical analysis?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Tool launch".

- You’ll see a number of software, platforms, and applications that transformed technical analysis. These include charting tools, spreadsheet programs, and trading platforms having shaped modern market analysis and trading practices.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 17th–18th century | Early origins | The roots of technical analysis stretch back to early modern markets, where traders seek practical ways to interpret price movements. In Japan, rice futures markets in Osaka flourish, and the legendary merchant Munehisa Homma develops candlestick charting to visualize shifts in supply, demand, and trader psychology.[1][2] Meanwhile in Europe, Amsterdam emerges as a financial hub, and Joseph de la Vega’s Confusión de Confusiones (1688) vividly describes speculation and price swings in Dutch East India Company shares. These early efforts are not formal theories but practical tools, relying on charts and behavioral insights. Together, they establish the idea that markets follow observable patterns, setting the stage for later systematic approaches.[2] |

| Late 19th – Early 20th century | Foundational Period | By the late 1800s, modern stock exchanges in London and New York create an environment ripe for structured analysis.[2] Charles Dow, co-founder of The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones & Company, publishes editorials that become the foundation of what would be known as Dow Theory. He outlines principles of price trends, market phases, and the interplay of averages, suggesting that markets move in discernible patterns rather than random fluctuations. His colleague William P. Hamilton later expands these ideas, cementing their influence. In the 1920s and 1930s, Richard W. Schabacker continues this tradition with works such as Stock Market Theory and Practice (1930) and Technical Market Analysis (1932), systematizing Dow’s ideas and expanding on market cycles, trend analysis, and chart patterns. Schabacker’s writings bridge the early Dow theorists with later practitioners, earning him recognition as the “father of technical analysis.”[2][1][3][4] |

| Mid 20th century – 1980s | Expansion and formalization | The mid-20th century sees technical analysis expand rapidly, fueled by the advent of computers and broader interest in market strategies. Richard W. Schabacker, and later Robert D. Edwards and John Magee with their seminal Technical Analysis of Stock Trends (1948), codify chart patterns such as head and shoulders, double tops, and triangles. As computing spreads in the 1960s–80s, traders develop mathematical indicators like the Relative Strength Index (RSI), Moving Average Convergence Divergence (MACD), and Bollinger Bands. These tools allow markets to be analyzed with greater precision and consistency. At the same time, academia challenges TA through the Efficient Market Hypothesis, sparking debates about its legitimacy. Yet in practice, TA gains mainstream acceptance among traders worldwide.[2][5] |

| 1990s–Present | Digital and AI Era | The digital revolution transforms technical analysis, making it accessible far beyond professional trading floors. Online brokers and charting platforms give retail investors access to tools once limited to specialists, spreading TA globally across stocks, forex, and commodities. Personal computers and the internet fuel the rise of real-time data visualization, while algorithmic and high-frequency trading integrates technical indicators into automated systems.[6] More recently, artificial intelligence and machine learning push the field further, enabling traders and institutions to analyze massive datasets and identify subtle, non-linear patterns. Technical analysis today operates as a hybrid discipline, blending its historical charting traditions with cutting-edge computational models, ensuring relevance in an era of rapid technological and financial innovation.[2] |

Summary by century

| Century | Event Type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50th century B.C. | Early practices | Settlers in the Jordan Valley initiate early market practices by engaging in trade with nomadic groups. This period represents one of the earliest instances of organized economic interaction between settled agricultural communities and mobile herders. These exchanges likely involve the barter of goods such as agricultural produce and livestock, laying the groundwork for future trade networks. This foundational economic activity contributes to the evolution of more complex market systems, setting the stage for the emergence of formalized trading practices.[7] | |

| 30th century B.C. | Early practices | Ancient Babylonians significantly advance economic practices by establishing a formal system of weights and measures. This development enables more accurate trade and commerce, as merchants can standardize the quantity and value of goods exchanged. Additionally, the Babylonians formalize business transactions through written contracts, which provide legal frameworks for agreements and reduce disputes. The introduction of limited partnerships allows individuals to pool resources while limiting personal liability, facilitating larger trade ventures and investments.[7] | |

| 24th century B.C. | Market development | Sargon of Akkad establishes the first Mesopotamian empire, a significant milestone that underscores the critical role of trade and market practices in ancient economies. Under Sargon's rule, the empire facilitates extensive trade networks across the region, connecting diverse cultures and enhancing economic exchange. Sargon implements policies that promote commerce, including the standardization of weights and measures, which streamline transactions and buid trust among traders. The empire's administrative innovations and centralize governance further support market activities, allowing for the growth of urban centers and marketplaces. This emphasis on trade not only enrichs Mesopotamia economically but also sets the foundation for future market analysis and economic strategies.[7] | |

| 20th century B.C. | Market development | Decentralized city-states emerge after the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, each run by merchants conducting trade.[7] | Mesopotamia |

| 10th century B.C. | Market development | Political decentralization in the Iron Age allows merchants greater freedom in business activities and physical movement.[7] | Various regions |

| 8th century B.C. | Early practices | Babylonians document commodity values and keep diaries of astronomical observations and prices, an early form of technical analysis.[7] | Babylonia |

| 7th century B.C. | Introduction of Coinage | The kingdom of Lydia, located in what is now western Turkey, introduces the first known coins, a major innovation in the history of trade. Made of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, these coins are stamped with official symbols, certifying their weight and value. This development revolutionizes commerce by replacing barter with a standardized medium of exchange, making transactions more efficient and reliable. The introduction of coinage in Lydia facilitates wider trade networks and contributes to economic growth, establishing a foundational element for modern financial systems.[7] | Lydia |

| 5th century B.C. | Greek Banks, Speculation, Religious Dedication | Greek banking emerges, with evidence related to the Athenian grain trade. Traders at the Athenian stock exchanges manipulate prices based on news. A guild of merchants dedicate a temple to Mercury, the god of trade.[7] | |

| 4th century B.C. | Technical Analysis, Speculation, Market Sentiment | Athenian merchants use geographical and environmental information to develop methods for technical analysis. They change their strategies based on timely news and data on price fluctuations, attempting to predict future prices and infer market sentiment.[7] | Athens |

| 1st century B.C. - 1st century A.D. | Economic Prosperity | Roman commerce reaches its height, characterized by market-oriented agricultural production and an increase in demand for luxuries. Although scarce, evidence of price records from ancient Rome suggests a market economy where prices contain information about the supply of and demand for goods.[7] | |

| 9th century | Background | The world's first known printed book, a Buddhist sutra, is produced in China.[7] | China |

| 12th-13th century | Market development | The Champagne fairs attract traders from various countries, dealing in textiles, leather, and financial transactions.[7] Wang Chih writes A Further Collection of Miscellaneous Items, highlighting the market jargon and practices of brokers.[7] | Champagne, France, China |

| 13th century | Market development | Sophisticated traveling merchants and sedentary merchants conduct international trade and communicate through land mail. The market economy and urban growth peak in China; Marco Polo describes Su-chou and Hang-chou.[7] | Various regions |

| 16th century | Political Change | Hideyoshi Toyotomi ends the currency economy in Japan, leading to the development of sophisticated trading methods.[7] | Japan |

| 17th century | Early practices and charting | In the Netherlands, traders of the Dutch East India Company began recording stock price fluctuations on paper, producing some of the first rudimentary charts to visualize market movements.[2][8] Amsterdam-based merchant Joseph de la Vega documented Dutch financial markets in Confusion of Confusions.[1] In Japan, the rice futures market was established in Osaka, leading to the development of candlestick charting.[5][4] Meanwhile, in China, *A Record of the Customs of Wu* described the growth of market towns and commerce, reflecting the global expansion of organized trading practices.[7] | Netherlands, Japan, China |

| 18th century | Development of Candlestick Charting, Publications | Japanese rice trader Munehisa Homma pioneers candlestick charting, representing opening, closing, high, and low prices. He develops Sakata charts and documents his techniques in influential works such as *The Fountain of Gold* and *The Three Monkey Record of Money*, laying the foundations for Japanese technical analysis.[7][8][4] | Japan |

| 19th century | Dow Theory Development, Price Charts, Social Attitudes | Charles Dow, co-founder of Dow Jones & Company and The Wall Street Journal, studies stock market data and publishes editorials outlining principles that form the basis of Dow Theory, analyzing market trends and fluctuations.[9] The use of price charts becomes prevalent in France, England, and Bavaria, enhancing market visualization techniques. During this period, financial speculation gains recognition as a | |

| 20th century | Systematization and modern evolution | Following the 1929 crash, analysts such as Ralph Nelson Elliott, W.D. Gann, and Richard D. Wyckoff developed systematic schools of analysis. Technical Analysis of Stock Trends (1948) by Edwards and Magee formalized chart patterns like head-and-shoulders, triangles, and double tops. From the mid-20th century, advances in computer technology enable the creation of sophisticated indicators such as the Moving average convergence/divergence, Relative strength index, and Bollinger Bands. In the 1970s–1980s, technical analysis surge in popularity with tools like Fibonacci retracements, while the Efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) gain prominence, challenging its validity. The 1980s see personal computers and software such as MetaStock and TradeStation revolutionize charting and backtesting. In the 21st century, platforms like TradingView and algorithmic systems integrate technical tools with machine learning, embedding technical analysis into both retail and institutional strategies.[10][8] |

Full timeline

Inclusion criteria

We include:

We do not include:

- Notable events without reference dates.

- Focus on statistical deviation and dispersion events.

Timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5000 B.C. | Market development | In the Neolithic era, settlers in the Jordan Valley engage in trade with nomads, exchanging resources such as salt and sulfur for obsidian and domesticated animals. This marks the early roots of market exchanges.[7] | Jordan Valley |

| 50th century B.C. - 20th century B.C. | Market development | Settlers in the Jordan Valley engage in trade with nomads, marking the early roots of market exchanges. Ancient Babylonians develop a system of weights and measures, formalize business deals with contracts, and introduce limited partnerships. Sargon the Great establishes the first Mesopotamian empire, highlighting the importance of trade and market practices. Decentralized city-states emerge after the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, each run by merchants conducting trade.[7] | |

| 3000 B.C. | Pre-modern financial practice | Ancient Babylonians develop a system of weights and measures, formalize business deals with contracts, and introduce limited partnerships, laying the groundwork for technical analysis.[7] | Babylonia |

| 2400 B.C. | Market development | Sargon the Great establishes the first Mesopotamian empire with its capital at Agade, where merchants play a significant role in economic life, highlighting the importance of trade and market practices.[7] | Mesopotamia |

| 2000 B.C. | Market development | After the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, decentralized city-states emerge, each run by merchants who establish trading colonies and conduct trade, a critical factor in market analysis.[7] | Mesopotamia |

| 1000 B.C. | Market development | In the Iron Age, political decentralization allows merchants greater freedom in their business activities and physical movement, further enhancing trade practices.[7] | Various regions |

| 747 B.C. | Trade Infrastructure | Babylonians begin documenting the values of six commodities (barley, dates, mustard/cuscuta, cress/cardamom, sesame, and wool) in astronomical diaries, resembling modern practices of tracking selected stocks.[7] | Babylonia |

| 700 B.C. | Early practice | Babylonians keep diaries of astronomical observations and commodity prices, recording price fluctuations and market trends, an early form of technical analysis.[7] | Babylonia |

| 650 B.C. | Market development | The earliest evidence of coins comes from the Lydian capital of Sardis. The use of coins for commercial purposes became widespread in Greece by the fifth century B.C., facilitating trade and market activities.[7] | Lydia |

| 651 B.C. | Early practice | The earliest known Babylonian diary, covering 12 months, documents astronomical observations and market prices, providing a continuous record of market trends and fluctuations.[7] | Babylonia |

| 585 B.C. | Speculation | Thales of Miletos corners the oil market by buying or renting all the oil presses after forecasting a good harvest of the oil crop.[7] | Miletos |

| 561 B.C. | Market development | During his tyranny in Athens, Pisistratus introduces market-oriented economic institutions, encouraging crop specialization and urbanization, which would help develop the market system further.[7] | Athens |

| 500 B.C. | Infrastructure | Greek banking emerges, with the earliest evidence related to the Athenian grain trade. Banks, initially temples, become private institutions, playing a crucial role in trade and market economies.[7] | Greece |

| Early 5th century B.C. | Religious Dedication | A guild of merchants in Greece dedicate a temple to Mercury, the Roman god of trade, commerce, and profit. This religious dedication highlights the strong cultural significance of trade within Greek society and the reverence merchants hold for deities associated with commerce. By establishing a temple, merchants seek divine favor and protection over their economic activities, emphasizing the integration of religious practices with business pursuits.[7] | Greece |

| 400 B.C. | Early practice | Babylonians use astronomical diaries to record market data and make forecasts based on celestial observations, demonstrating an early form of technical analysis.[7] | Babylonia |

| 330 B.C. | Speculative strategy | Cleomenes of Naucratis, an administrator in the service of Alexander the Great, orchestrates one of history’s earliest recorded instances of market manipulation. By planning a “wheat corner,” he seeks to restrict wheat production in Egypt, thereby reducing supply to drive up prices and exert control over the market. Cleomenes aims to profit by imposing his own prices on this essential commodity, illustrating an early form of speculative trading. This attempt at market control highlights the long-standing practices of speculation and manipulation in financial markets, predating formalized trading systems and laying foundational elements for the eventual development of regulatory and analytical approaches in commerce.[7] | Greece |

| Augustan age (c. 43 B.C.-18 A.D.) | Market development | During this time, Roman commerce thrives, marking a period of significant economic prosperity. Under Augustus's rule, the Roman Empire experiences increased stability and expansion, which fuels market-oriented agricultural production and a burgeoning demand for luxury goods. Trade networks extend across the empire and beyond, facilitating the exchange of goods such as spices, silks, and precious metals from distant regions. This period sees enhanced infrastructure, including roads and ports, which support the flow of commerce.[7] | Rome |

| Early Roman Empire | Early practice | Price data exhibits seasonal patterns, leading to arbitrage opportunities based on these patterns. Recognizing and capitalizing on seasonal trends would become a key strategy in technical analysis.[7] | Rome |

| 1150-1300 | Infrastructure | The Champagne fairs in France flourish, marking a "Golden Age" of trade fairs that become central to European commerce. Held in the Champagne region, these fairs attract merchants from across Europe, facilitating the exchange of textiles, leather, spices, and other goods sold by weight. Beyond tangible goods, the fairs are also hubs for financial transactions, including currency exchange and credit arrangements, laying early groundwork for modern financial practices. The Champagne fairs' well-organized schedules and secure environments foster a network of reliable trade, which contribute to economic growth and the spread of commercial techniques that would later influence the development of technical analysis in market transactions.[7] | France |

| 1202 | Publication | Liber Abaci by Leonardo Fibonacci is published, introducing Arabic numbers and commercial arithmetic methods.[7] Fibonacci numbers would later become foundational in technical analysis, particularly in Fibonacci retracements and extensions used to predict price levels. | Italy (Pisa) |

| 1278 | Publication | The compilation of the Memoria de tucte le mercantile in Italy marks a significant advancement in the realm of business literature. This instructional manual provides merchants with guidelines on various commercial practices, including trade techniques, financial management, and market strategies. Notably, it includes an astrological appendix, reflecting the contemporary belief in astrology’s influence on market conditions and decision-making. The integration of astrological insights with practical business advice illustrates the era's attempt to blend empirical and mystical approaches to commerce. This manual not only serves as a resource for merchants but also contributes to the evolving understanding of market dynamics, influencing future practices in trade and technical analysis.[7][11] | Italy |

| 1309 | Infrastructure | The city of Bruges establishes one of the earliest formal bourses, or financial exchanges, which becomes a central meeting place for traders across Europe. Named after the Van der Beurze family, whose residence hosts these gatherings, the Bruges bourse enables merchants to conduct business, negotiate contracts, and settle payments. This institution marks a shift towards organized financial markets, allowing for more efficient trade of goods, currencies, and securities. The Bruges bourse sets a precedent for similar exchanges in cities like Antwerp and Amsterdam, laying the foundation for modern stock exchanges.[12] | Belgium |

| 1300s | Instrument introduction | The Merchants of Venice begin trading debts, acting similarly to modern brokers.[13] | Italy |

| 1531 | Infrastructure | The world’s first official stock exchange is established in Antwerp, Belgium, where merchants gather to trade promissory notes, bonds, and other financial instruments. Unlike modern exchanges, this early bourse does not involve trading company stocks; instead, it facilitates transactions in government debt and other financial contracts. The Antwerp exchange introduces a structured marketplace for buyers and sellers, promoting transparency and reliability in financial dealings.[13] | Belgium |

| 1540 | Early practice | Christopher Kurz develops a technical trading system based on astrology in Antwerp.[7] Kurz's system, despite its basis in astrology, lays a foundation for technical analysis by attempting to predict market movements using historical data and cycles. | Belgium |

| 1585 | Market data introduction | The Amsterdam Bourse, one of the world’s first formal stock exchanges, produces the earliest recorded list of price quotations. This list provides traders with standardized information on the prices of various goods and commodities, fostering transparency and enabling more informed trading decisions. By documenting price changes over time, the Amsterdam Bourse would play a pivotal role in the evolution of market analysis, as traders begin to recognize patterns and trends within these recorded prices.[7] | Netherlands |

| 1587 | Market development | Hideyoshi Toyotomi ends the currency economy, prompting merchants to develop sophisticated methods, including technical analysis, to trade and analyze markets. Meanwhile, Japan unifies under a centralized feudal system established by generals Nobunaga Oda, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, and Ieyasu Tokugawa, leading to the development of rice exchanges.[7] | Japan |

| 1602 | Stock exchange launch | Shares of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) begin trading on the Amsterdam Bourse, marking a milestone as the first publicly traded company. This event introduces the concept of joint-stock ownership, allowing investors to buy and sell shares in the company and share in its profits. The Amsterdam Bourse thus becomes the world's first stock exchange where company shares are actively traded, fostering the development of investment practices and shareholder rights. The VOC’s public listing helps establish a framework for equity trading, which would later drive the evolution of financial markets.[7][13] | Netherlands |

| 1609 | Infrastructure | The Bank of Amsterdam is founded as northern Europe’s first exchange bank. It aims primarily to curb the circulation of debased coins, rather than to guard against private bank failures. By accepting only high-quality coinage, the Wisselbank is able to stabilize the Dutch currency system, maintaining a consistent coinage standard for about 150 years. Its stability and trustworthiness establishes Wisselbank money as a cornerstone of European commerce and finance. Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776), would commend the bank’s money for its superior reliability compared to other forms of currency, underscoring its pivotal role in the region’s economy. This institution sets a model for modern banking practices and would influence the development of financial systems across Europe.[14][7][15] | Netherlands |

| 1621 | Instrument introduction | Shares of the West India Company begin trading on the Amsterdam Bourse. Commodities trading, such as that facilitated by the West India Company, introduces price volatility and trading patterns observed in technical analysis.[7] In the same year, Dutch colonists establish New Amsterdam in New Netherlands, laying the groundwork for what would become a major financial center.[7] | Netherlands |

| 1633 - 1637 | Speculative bubble | Amsterdam experiences the famous tulip mania, one of the earliest recorded speculative bubbles. During this period, tulip bulbs, particularly rare varieties, soar in value as people invest heavily, expecting continuous price increases. At the peak, a single bulb would cost more than a house. However, prices eventually crash, leaving many investors with substantial losses. Tulip Mania serves as a classic example of market psychology and the dynamics of speculative bubbles, illustrating how emotions and herd behavior can drive markets beyond reasonable valuations.[7] | Netherlands |

| 1653 | Infrastructure | Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch Director-General of New Amsterdam (later New York City), orders the construction of a wooden stockade stretching 1,340 feet in length and 12 feet in height. This defensive barrier, known as Wall Street, is built to protect the settlement from potential attacks by Indigenous tribes and the British. Located along what would later be the famous financial district, Wall Street would evolve over time from a simple fortification into a central hub for trade and commerce.[7] | United States |

| 1660 | Market development | Europe experiences societal and scientific revolutions, setting the stage for modern capitalism.[7] Societal changes and the rise of capitalism provides the economic environment for the development of technical analysis methodologies. | |

| 1663 | Speculative practice | The Grain Act marks a pivotal legal change in England by legalizing forestalling and regrating practices, which encourages speculative activities in grain trading. Forestalling allows merchants to purchase goods before they reach the market, while regrating permits them to buy and resell goods at a profit within the same market. This legislation aims to stabilize grain prices and ensure a steady supply, fostering a more competitive trading environment. By facilitating speculative practices, the Grain Act not only stimulates free trade but also lays the groundwork for more sophisticated market strategies.[7] | England |

| 1675 | Publication | French merchant Jacques Savary publishes Le Parfait Négociant, a comprehensive guide on mercantile practices, which becomes a foundational work in business education. This manual provides practical advice on various aspects of commerce, including accounting, contracts, insurance, and maritime trade. Savary’s work emphasizes ethical conduct, proper record-keeping, and the importance of understanding market conditions—principles that were instrumental in shaping the emerging field of commerce. Le Parfait Négociant not only serves as an essential resource for merchants but also contributes to the development of systematic business practices, laying early groundwork for modern economy.[7] | France |

| 1680 | Infrastructure | London coffeehouses such as Jonathan's Coffee House become popular venues for brokers and investors to conduct business, marking an early form of organized securities trading. These coffeehouses serve as informal exchanges where merchants, traders, and financiers gather to discuss market trends, trade shares, and exchange information. Jonathan's Coffee House, in particular, becomes a central hub for trading stocks and commodities, laying the foundation for the establishment of the London Stock Exchange.[13] | |

| 1688 | Publication | Joseph de la Vega, an Amsterdam-based merchant, publishes Confusion de Confusiones. This early work offers a comprehensive documentation of the Dutch financial markets of the time, providing early insights into market behavior and patterns. De la Vega describes various speculative techniques and methods for predicting stock price movements, making it one of the earliest known works on technical analysis. His observations and methodologies lay the groundwork for future developments in the field of financial analysis and trading.[1][2][9][7][8] | Netherlands |

| 1697 | Infrastructure | The Dojima Rice Exchange is established in Osaka, Japan, becoming the world’s first organized commodity futures exchange. It emerges during a time when rice functions as both a staple food and a form of currency, with samurai and officials often paying in rice. This demand leads to the innovation of rice futures contracts, allowing merchants to lock in prices and mitigate market risk. Transactions are centralized along Osaka’s Dojima River. Though dissolved in 1939, its legacy would continue through the Osaka Dojima Commodity Exchange, where rice and other agricultural goods are still actively traded.[16][7] | Japan |

| 1698 | Infrastructure | The origins of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) begin at Jonathan's Coffee House in London, where brokers and investors gather to trade shares and commodities. This informal market becomes a central hub for financial dealings in England. As trading activity increases, the need for regulation and organization grows, leading to the formal establishment of the London Stock Exchange in 1801. The LSE would become one of the world's most influential financial institutions, playing a critical role in global capital markets. Its development marks a major step in the evolution of modern securities trading and the global financial system.[17] | England |

| 1710 | Instrument introduction | The Dojima Rice Exchange in Osaka, Japan, establishes a rice futures market where rice coupons representing future delivery are traded. This market marks the introduction of futures contracts and employs early technical analysis techniques, such as candlestick charting.[7][9][1][5] | Japan |

| 1711 | Trading development | The South Sea Company is founded in Great Britain, marking a notable advancement in financial innovation and trading practices. Created to consolidate and manage national debt, the company is granted a monopoly on trade with Spanish colonies in South America, despite limited access to these markets. In 1720, the company’s shares would skyrocket in value due to rampant speculation, leading to the infamous South Sea Bubble, which would burst later that year, resulting in substantial financial losses.[18] Despite its eventual collapse and cessation of operations in 1853, the South Sea Company’s story would often be cited as a cautionary tale about speculative bubbles and market manipulation, highlighting the risks inherent in investing and influencing the development of modern financial regulations.[13] | Great Britain |

| 1752 | Market development | New York establishes its first formal market, organized by local merchants for trading slaves and cornmeal. This market is a significant development in the city’s economic history, facilitating structured trade and commerce. The establishment of a formal trading venue not only streamlines transactions but also highlights the importance of agricultural products and the grim reality of the slave trade in the burgeoning economy of colonial America. This market lays the groundwork for New York's evolution into a major commercial hub, influencing the future dynamics of trade and the development of more diverse markets in the region.[7] | United States |

| 1755 | Publication | Japanese rice trader Honma Munehisa publishes The Fountain of Gold, a seminal work that outlines his trading strategies for the rice markets. Homma’s book introduces the concept of buying when prices decline and selling when they rise, a principle that would remain central to trading strategies. Known as one of the pioneers of technical analysis, Homma also develops candlestick charting techniques to track price movements, which provides insights into market psychology. His work lays the foundation for modern technical analysis tools, and his methods would continue to influence traders worldwide, particularly in the interpretation of price patterns and market trends.[7][9][1] | Japan |

| 1786 | Data visualization development | Scottish engineer William Playfair creates one of the earliest known line charts, plotting ten years of Royal Navy expenditures. Because audiences are unfamiliar with abstract visualizations, he includes explanations on interpreting changes over time. The line chart, which connects ordered data points with straight segments, is used to show trends across time intervals, often called a run chart. Playfair’s innovation helps establish time-based visualization, inspiring future use of graphs in data analysis. He also pioneers other major chart types, including the bar chart and pie chart.[19] | |

| 1790 | Infrastructure | Philadelphia becomes the site of the first formal stock exchange in the United States, known as the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. This exchange is established to facilitate the trading of government securities, including bonds issued to fund the Revolutionary War, and later expanded to include stocks and other securities. It provides a structured platform for buyers and sellers, promoting liquidity and transparency in financial markets. The PHLX sets a precedent for the development of other exchanges across the United States, including the New York Stock Exchange, and plays a crucial role in the early growth of the U.S. financial system.[13][7] | United States |

| 1792 | Infrastructure | The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) is established under a buttonwood tree on Wall Street, quickly rising in prominence.[13] | |

| 1792 | Publication | Wu Zhongfu compiles The Merchant’s Guide from earlier manuals Essentials for Travelers and Essentials for Tradesmen.[7] | China |

| 1830s | Data visualization development | The emergence of price charts for visualizing the market becomes prevalent in France, England, and Bavaria.[7] | France, England, Bavaria |

| 1863 | Publication | Shareholder’s Circular and Guardian advocates that participating in financial markets is in one’s personal and reproductive self-interest.[7] | |

| 1867 | Trading system evolution | The first stock ticker is introduced by Edward Calahan, transmitting stock prices over telegraph lines. This allows near real-time market data for the first time. | |

| 1870 | Societal impact | Lefevre suggests that investing can promote social harmony by uniting the bourgeoisie and working classes into a single "investing class."[7] | |

| 1870s | Data visualization development | The Kagi chart is developed in Japan to track price movements, initially for rice trading. Unlike traditional charts like candlesticks, it is largely independent of time, reducing random noise and highlighting clear trends. Direction changes occur only after a specific price movement, making it effective for identifying supply and demand levels. Investors use Kagi charts to support stock decision-making, often alongside other analytical tools. Its main advantage is providing a simplified view of price action, emphasizing meaningful movements over short-term fluctuations.[20] | |

| 1878 | Technological infrastructure | The New York Stock Exchange installs its first telephone, allowing brokers to place orders faster than by messenger or telegraph.[21] | United States |

| 1884 | Analytical theory development | Charles Dow, co-founder of The Wall Street Journal, studies stock market data and creates an average of the daily closing prices of 11 important stocks. This leads to the development of Dow Theory, which correlates market patterns with the Dow Jones Industrial Average, laying the foundation for modern technical analysis. Dow believes stock price movements reflect the composite knowledge of all market participants and can predict future business conditions.[9][3][22][2][5][4][10] | United States |

| 1885 | Publication | Dow presents the "market discounts everything" principle and discusses the rotation of bullishness and bearishness in his editorials.[7] | |

| 1887 | Infrastructure | The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) is founded during South Africa’s first gold rush. It would later join the World Federation of Exchanges in 1963 and shift from floor-based trading to an electronic system in 1996. The JSE would expand by acquiring the South African Futures Exchange in 2001 and the Bond Exchange in 2009, while launching AltX in 2003 for smaller firms. Listed in 2005 under “JSE,” it remains Africa’s largest exchange, hosting over 400 companies by 2022, including Richemont, Anglo American, and Naspers.[23] | South Africa |

| 1891 | Infrastructure | The Shanghai Sharebrokers' Association is established, marking the creation of China's first stock exchange. Initially dominated by local banks and companies, foreign institutions, particularly from Hong Kong and Shanghai, soon gains control over most shares. By 1904, the Association expands to Hong Kong. In 1920 and 1921, the Shanghai Securities and Commodities Exchange and the Shanghai Chinese Merchant Exchange would be founded, merging in 1929 to form the Shanghai Stock Market. Trading ceases in 1941 under Japanese occupation and again in 1949 after the Communist Revolution. Following economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, the Shanghai Stock Exchange would reopen in 1990 alongside the Shenzhen Exchange.[24] | China |

| 1896 (May 26) | Index creation | The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) is first published, starting at 40.94 points with 12 industrial companies, including General Electric, American Tobacco, and U.S. Rubber. Created by Charles Dow and Edward Jones, it follows the earlier 1884 Dow Jones Railroad Average. Over time, the DJIA would expand to 20 stocks in 1916 and 30 in 1928, crossing 1,000 points in 1972 and 10,000 in 1999. Now maintained by S&P Dow Jones Indices, it reflects 30 major U.S. corporations and remains a key economic indicator.[25] | United States |

| 1898 | Technical analysis method | The technique of Point and Figure (P&F) charting is first introduced by "Hoyle" in his book The Game in Wall Street. The method quickly gains popularity among traders as a way to visualize price movements, unlike traditional time-based charts. P&F charts use columns of Xs to represent rising prices and Os for falling prices, offering a simplified view of price action. Initially referred to as "fluctuation" or "figure charts," the method would evolve over time into a distinctive charting system. It would be further developed by Victor Devilliers in 1933 and popularized by Chartcraft in the 1940s, leading to its widespread use today.[26] | |

| 1900 | Foundational theory | Louis Bachelier publishes The Theory of Speculation, introducing ideas foundational to stochastic processes in markets.[27] | France |

| 1902 | Theory introduction | Charles Dow considers the relationship between volume and price in The Wall Street Journal.[7] After his death, his followers would expand on his ideas and develop chart-based trading strategies.[5] | United States |

| 1910 | Technical analysis method | American stock market investor Richard D. Wyckoff, under the pseudonym “Rollo Tape,” publishes Studies in Tape Reading, laying the foundation for what would become the Wyckoff Method of technical analysis. His approach focuses on interpreting price and volume to reveal the intentions of major market players, known as the “Composite Operator.” Wyckoff’s later work in the 1930s formalizes three core principles—supply and demand, cause and effect, and effort versus result. The method would remain influential, guiding traders in identifying accumulation and distribution phases across equities, commodities, and digital assets.[28][29][30] | United States |

| Early 20th century | Speculative technique | Traders like Jesse Livermore use ticker tape to track market prices and anticipate market movements.[5] | United States |

| 1922 | Publication | William Peter Hamilton publishes The Stock Market Barometer, which formalizes and expands on Charles Dow's ideas. This work lays the groundwork for the Dow Theory, emphasizing the predictive power of stock market averages.[10] | United States |

| 1926 | Analytical theory development | Colonel Leonard Ayres of the Cleveland Trust Company first calculates and analyzes Advance-Decline Data to measure market breadth and sentiment by comparing advancing and declining stocks and their trading volumes. James Hughes later advances this work with Market Breadth Statistics, and in 1931 Barron’s begins publishing AD numbers. Although initially overlooked, AD data would gain prominence in the early 1960s when Richard Russell incorporates them into his Dow Theory Letters and Joseph Granville uses them in his Granville Market Letter to assess overall market strength.[31] | United States |

| 1932 | Publication | Robert Rhea publishes The Dow Theory, a book that synthesizes and expands upon the market concepts developed by Charles Dow, the co-founder of Dow Jones & Company. Rhea, building on earlier works by Samuel Nelson and William Peter Hamilton, formalizes Dow’s observations into a coherent theory of market behavior. His work introduces key principles such as the three types of market movements (primary, secondary, and short-term trends), the discounting nature of stock indices, and the belief that market manipulation is only possible in the short term. Rhea also emphasizes that Dow Theory, while useful, is not infallible.[32] | United States |

| 1930s | Theory introduction | Edson Gould uses technical analysis to predict Dow Jones Index movements, gaining widespread recognition. Over the following decades, he would make accurate market predictions and develop indicators like the Senti-Meter, earning a reputation as a market wizard.[4][22] | United States |

| 1930 | Publication | Richard W. Schabacker publishes Stock Market Theory and Practice, a comprehensive guide on stock market fundamentals, technical analysis, and risk management. Covering market history, trends, charting, and investment strategies, this book would remain a key text in understanding market intricacies and making informed investment decisions.[33] | |

| 1932 | Publication | Robert Rhea publishes The Dow Theory, providing further insight into Dow's work. In the following years, he would enhance the Dow Theory and popularize technical analysis through newsletters in his series Dow Theory Comments.[9][22][4] | United States |

| 1933 | Data visualization development | The Point and Figure chart is formalized by Victor Devilliers, who provides the first dedicated manual on this unique technical analysis method. Unlike time-based charts, Point and Figure (P&F) charts plot price movements only, using columns of X’s for rising prices and O’s for falling ones. The technique, first mentioned in “Hoyle’s” The Game in Wall Street (1898), is later popularized by Chartcraft Inc. in the 1940s. Analysts like Mike Burke and Thomas Dorsey refine it further, while Jeremy du Plessis would trace its evolution from simple price records to a structured charting system.[34] | |

| 1935 | Tool launch | W. D. Gann introduces his theory of Gann angles in The Basis of My Forecasting Method, where he describes the use of straight lines on price charts to establish relationships between time and price. The most crucial Gann angle is the 1x1, a 45° line representing a one-unit price change per one unit of time. Other angles, such as the 2x1 and 3x1, represent steeper slopes. Critics would question the legitimacy of Gann’s methods, pointing out that the positioning of the angles can be arbitrary and not scientifically grounded, though Gann’s approach would remain influential in technical analysis. | |

| 1935 | Theory introduction | American accountant Ralph Nelson Elliott makes a significant prediction regarding the stock market's bottom using what would be known as Elliott wave principle. Based on his analysis of market price patterns, Elliott theorizes that markets move in predictable, repeating cycles influenced by collective investor psychology. His prediction of the market bottom that year demonstrates the practical application of his theory, which involves identifying wave patterns within price movements to forecast future trends. Elliott's work provides a foundation for technical analysis, as traders begin to apply wave principles to anticipate market shifts, solidifying his impact on financial forecasting and market analysis techniques.[9][22] | United States |

| 1990 | Indicator development | Paul L. Dysart Jr. introduces the Negative Volume Index (NVI) and Positive Volume Index (PVI) to analyze market trends and reversals through trading volume. He creates two cumulative series—one for days when volume rises (PVI) and another for days when it falls (NVI). A former Chicago Board of Trade member, Dysart later publishes The Trendway market letter (1933–1969) and also develops the 25-day Plurality Index. Widely regarded as a pioneer of volume-based analysis, Dysart would be praised as “one of the most brilliant” early market technicians.[35] | |

| 1937 | Indicator development | The Hindenburg disaster inspires the later naming of the Hindenburg Omen, a technical analysis pattern created by Jim Miekka to predict potential stock market crashes. Based on Norman G. Fosback’s High Low Logic Index (HLLI), the indicator measures simultaneous new highs and lows on the NYSE to gauge market instability. Under normal conditions, markets move uniformly, but when many stocks hit both highs and lows together, it signals internal weakness. A positive 50-day rate of change and repeated occurrences strengthen the warning, suggesting elevated crash probability within short timeframes.[36] | |

| 1938 | Publication | H.M. Gartley publishes a series of detailed annotated charts aimed at educating readers on the common features and patterns found in market trends. These charts, presented in his influential book Profits in the Stock Market, analyzes recurring market movements and introduced what would later become known as the “Gartley pattern”—a specific harmonic pattern used to predict price reversals. Gartley’s work emphasized the importance of technical analysis and pattern recognition, offering traders tools to better understand and anticipate market behavior. His contributions lay foundational concepts for future developments in technical analysis and harmonic trading strategies.[5] | United States |

| 1946 | Publication | Ralph Nelson Elliott publishes Nature’s Law: The Secret of the Universe, his final and most comprehensive work, just two years before his death. This book encapsulates Elliott theories on how social behavior and market movements are interconnected through predictable wave patterns. Elliott argues that these waves, governed by natural laws, reflect human psychology and can be observed across various fields, not just in trading. Nature's Law would remain a pivotal text for those studying market cycles, technical analysis, and the broader implications of Elliott's theory on human behavior.[9] | United States |

| 1948 | Publication | Robert D. Edwards and John Magee publish Technical Analysis of Stock Trends, the first book to present a structured methodology for analyzing market behavior through technical analysis. The book would remain a cornerstone of investment literature. It introduces key concepts such as Dow Theory and Magee’s “basing points” procedure, and includes expanded material on commodity, short-term, and futures trading. Widely regarded as a classic, it continues to serve as an essential resource for technical traders, investors, and finance professionals navigating various market conditions.[37][22][38][22][4][10][3] | United States |

| 1949 | Trading system development | Richard Donchian founds Futures Inc., the first publicly available managed futures fund, marking a pioneering moment in investment strategy and fund management. Donchian’s fund introduces diversified, trend-following strategies, which focus on identifying and capitalizing on long-term market trends across various commodity futures. This approach helps mitigate risk by spreading investments over multiple assets and highlighted the benefits of systematic trading rules. Donchian's work lays the groundwork for modern trend-following techniques and is considered foundational in the development of managed futures funds, significantly influencing the practice of technical analysis and the trading systems used in today’s financial markets.[5] | United States |

| 1949 | Investment strategy development | Alfred Winslow Jones establishes the first hedge fund, pioneering a new approach to investing by combining both long and short positions to hedge against market fluctuations. Jones's strategy involves leveraging his investments and using tactical short selling to mitigate risk while maximizing returns, which allows him to “surf” the market’s mood swings and capitalize on market inefficiencies. This innovative model sets the foundation for modern hedge funds, influencing future investment strategies focused on risk management and strategic positioning to achieve consistent returns, regardless of market conditions.[39][5] | United States |

| 1950 | Trading strategy development | Richard Donchian develops the Turtle Trading Rule, an early systematic trend-following method. This concept would later evolve into the Donchian Channel indicator, which tracks the highest high and lowest low over a set period to identify breakouts and potential trend reversals. By highlighting whether price movements are likely to continue or reverse, Donchian’s innovation lays the foundation for modern technical trading systems and greatly influences later generations of traders, including those behind the famed Turtle Trading experiment of the 1980s.[40] | |

| 1960 | Market analysis tool | The Keltner channel is introduced by Chester W. Keltner in his book How to Make Money in Commodities. Originally called the ten-day moving average trading rule, it consists of a central 10-day simple moving average of the typical price—the average of each day’s high, low, and close—with channel lines above and below, spaced by the average of recent trading ranges. A close above the upper line signals bullish strength, while a close below indicates bearish sentiment. Later analysts, including Linda Bradford Raschke, refine the method using exponential averages and the Average True Range (ATR).[41] | United States |

| 1962 | Market analysis tool | E.S.C. Coppock introduces the Coppock Curve, a long-term stock market indicator published in Barron's Magazine. Designed for monthly data, it sums a 14-month and 11-month rate of change, smoothed by a 10-period weighted moving average. Coppock, an economist, bases the periods on typical mourning durations, reflecting his view of market downturns as bereavements. The indicator generates buy signals when it rises from below zero but does not provide sell signals. Primarily for stock indexes like the S&P 500, it is trend-following and highlights established rallies rather than market bottoms.[42] | |

| 1963 | Indicator development | Joseph Granville popularizes On-Balance Volume (OBV) in his book Granville's New Key to Stock Market Profits. Originally called “continuous volume” by Woods and Vignola, OBV is a technical analysis indicator linking price and volume. It assigns positive or negative values to daily volume depending on whether prices close higher or lower, creating a cumulative total. Traders use OBV to confirm price trends: rising OBV with rising prices signals strength, while divergence—OBV failing to reach new highs—indicates potential weakness. It can be applied to individual stocks or overall market breadth.[43][44][45][46][47] | |

| 1967 | Organization | A group of New York-based technical analysts founded what would become the CMT Association, establishing one of the earliest professional communities dedicated to advancing the discipline of technical analysis. Originally formed to share ideas and formalize practices in market analysis, the organization evolved into a globally recognized credentialing body. Headquartered in New York City, the non-profit association now serves over 4,500 members in approximately 137 countries. Its flagship offering is the Chartered Market Technician (CMT) designation, awarded to individuals who demonstrate advanced proficiency in technical analysis by passing a rigorous three-level exam series. The CMT credential is also recognized by FINRA. | United States |

| 1969 | Trading system evolution | Instinet launches the world’s first electronic communication network (ECN) for trading stocks, marking the birth of modern fintech. This innovation sparks a revolution that would reshape global financial markets, laying the foundation for digital trading systems used today.[48] | United States |

| 1969 | Market analysis tool | Sherman and Marian McClellan develop the McClellan Oscillator and Summation Index, which become pioneering tools for market breadth analysis. Without computers, they manually calculate and chart data from the NYSE and AMEX, comparing eight years of results. Sherman introduces these indicators to the public through guest appearances on Charting The Market, gaining attention that leads to their book Patterns for Profit. Initially limited by manual computation, the later advent of personal computers would allow broader application. Today, these indicators are integrated into market analysis software, with updated editions containing decades of computer-generated data, demonstrating their enduring relevance in technical analysis.[49] | |

| Late 1960s | Market analysis tool | Goichi Hosoda, known as Ichimoku Sanjin, releases Ichimoku Kinko Hyo after developing it over three decades. Originally conceived in the 1930s, this Japanese method combines moving averages and time analysis to forecast price trends more accurately. Translating to “one glance equilibrium chart,” it features a distinctive “cloud” formation that visualizes support and resistance. Unlike standard moving averages, Ichimoku uses midpoints of highs and lows, not closing prices. The system also incorporates Time Theory, Wave Movement Theory, and Target Price Theory for comprehensive market analysis.[50][51][52][53] | Japan |

| 1970 | Organization | The Market Technicians Association (MTA) is founded as a small group of technical analysts dedicated to advancing the discipline of technical analysis. Over time, it would become a leading organization in the field, serving as a hub for the exchange of innovative ideas and research. The MTA would play a crucial role in shaping industry standards and promoting professional development among technical analysts, ultimately influencing the broader financial community and the evolution of technical trading methods.[54] | United States |

| 1971 | Technological advancement | The National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (Nasdaq) is established as the world’s first electronic stock market. This groundbreaking technological advancement transforms the way stocks are traded by replacing the traditional trading floor with a computerized system, allowing for faster and more efficient trading. Nasdaq introduces automated price quotations for over-the-counter stocks, increasing transparency and accessibility for investors. Its creation marks a significant shift in financial markets, paving the way for electronic trading and influencing the development of other global exchanges. Today, Nasdaq is known as one of the largest stock exchanges in the world.[13][48] | United States |

| 1973 | Theory development | Fischer Black and Myron Scholes publish their groundbreaking paper, "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities," in the Journal of Political Economy, introducing the Black-Scholes model for valuing options. This model enables the calculation of implied volatility by equating an option’s market price with its theoretical value. Implied volatility reflects the market's expectation of future price fluctuations. For the VIX, this concept is applied to S&P 500 index options, calculating expected volatility over a 30-day period. The VIX, derived from these options, serves as a key gauge of market sentiment and risk, reflecting anticipated stock market volatility. | |

| 1973 | Indicator development | Larry Williams publishes his book How I Made One Million Dollars… Last Year… Trading Commodities, introducing the Williams %R indicator. Developed from his trading experience since 1966, %R measures overbought or oversold conditions by comparing today’s closing price to the highest high and lowest low over the past ten days. The formula calculates the percentage distance from the recent high to the close relative to the total range. Readings near 0% indicate overbought conditions, while readings near 100% indicate oversold conditions. Williams emphasizes using %R within the context of dominant bull or bear markets for optimal trading signals.[55] | |

| 1973 | Market analysis tool | A paper introduces a method for calculating implied volatility, laying the groundwork for the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX). Developed from research by Menachem Brenner and Dan Galai in 1989 and implemented by Bob Whaley in 1992, the VIX measures expected 30-day volatility in the S&P 500 based on option prices. Known as the “fear index,” it reflects market sentiment and risk expectations. Although not directly tradable, VIX exposure is available through futures, ETFs, and ETNs, with variants tracking different market indexes and timeframes.[56] | |

| 1973 | Market analysis tool | The put-call ratio begins to be used as a key metric in options trading, coinciding with the introduction of exchange-traded options. This ratio measures the volume of put options relative to call options for a given asset, providing insight into overall market sentiment. A ratio below 1 generally signals bullish sentiment, while above 1 indicates bearishness. Extreme ratios can suggest overbought or oversold conditions, serving as a contrarian indicator. The put-call ratio would gain prominence during major market events, including the 1987 Black Monday crash and the dot-com bubble, helping traders assess market extremes and potential reversals.[57] | |

| 1974 | Index introduction | The Wilshire 5000 Index is introduced, covering virtually the entire U.S. equity market.[58] | United States |

| 1975 | System launch | The Philadelphia Stock Exchange (PHLX) launches the Philadelphia Automated Communication and Execution (PACE) system. This innovation allows for the electronic routing and execution of stock orders, significantly improving the speed and efficiency of trading. PACE links computers to automate transactions, reducing the reliance on manual, floor-based processes. This pioneering step not only enhances trading accuracy and speed but also positions PHLX as a technological leader among U.S. exchanges, paving the way for broader adoption of electronic systems in the financial markets.[59] | United States |

| 1976 | Publication | The Elliott Wave Theorist is first published by Robert Prechter as a monthly newsletter, offering Elliott wave analysis of financial markets and cultural trends. Initially, Prechter uses it to express his market opinions while working at Merrill Lynch. After leaving Merrill in 1979, he would continue the publication on a subscription basis. The newsletter would gain significant attention in the early 1980s, especially after its bullish stock market forecasts, eventually attracting around 20,000 subscribers. Despite a decline in subscriptions in the 1990s, it would remain influential and would earn recognition in financial circles for its insights and controversial predictions.[60] | United States |

| 1976 | Trading infrastructure | The New York Stock Exchange introduces the Designated Order Turnaround (DOT) system, an early step toward electronic trading. DOT enables brokers to route 100-share orders directly to floor specialists, bypassing traditional floor brokers. While the system streamlines order delivery, it does not provide full electronic execution since specialists still manually matched trades. Nevertheless, DOT marks a significant innovation in market infrastructure, improving speed and efficiency while laying the groundwork for future automation in stock trading and the eventual transition to fully electronic execution systems.[61] | United States |

| 1977 | Trading infrastructure | Instinet introduces the first U.S. stock quote montage, known as the Green Screen. This system displays consolidated quotes electronically, giving traders real-time access to market information that had previously been fragmented or slower to obtain. By centralizing and digitizing stock quotes, the Green Screen improves transparency and efficiency in trading, reducing reliance on traditional floor-based communication.[48] | United States |

| 1977 | Tool launch | CompuTrac releases its first commercial version, marking a major milestone in technical analysis software. This tool is capable of reading large datasets, calculating technical indicators, and displaying them graphically. By 1979, CompuTrac would expand to offer real-time online analysis, paving the way for modern retail trading platforms.[54] | United States |

| 1978 | Indicator development | J. Welles Wilder publishes New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems, which introduces a range of powerful technical indicators that would remain widely used until today. The book presents tools such as the Relative Strength Index (RSI), Average Directional Movement Index (ADX and DMI), Parabolic SAR, and Average True Range (ATR). These indicators would revolutionized the field of technical analysis by providing new methods to measure momentum, trend strength, and market volatility.[54] | United States |

| 1970s | Indicator development | Richard Arms develops the TRIN, or Arms Index, a short-term technical indicator based on advance-decline data. Calculated as the ratio of advancing to declining issues divided by the ratio of advancing to declining volume, TRIN values below 1 indicate bullish sentiment, while readings above 1 suggest bearishness. Continuously displayed on the NYSE, the index uses share volume rather than dollar value, giving greater weight to heavily traded low-priced stocks. The Arms Index would become widely used to gauge overall market sentiment when combined with other technical indicators.[62] | |

| 1980 | Indicator development | Donald Lambert introduces the Commodity Channel Index (CCI), an oscillator designed to identify price reversals, extremes, and trend strength in financial markets. Initially created for commodities, it soon gains widespread use in equities and currencies. The CCI measures a security’s deviation from its statistical mean by comparing its typical price to a moving average, scaled by a factor of 0.015 so that most values fall between −100 and +100. Traders adjust the averaging period to match different market timeframes and volatility levels.[63] | United States |

| 1982 | Organization | The Computer Asset Management Company (CAM) is founded with the goal of creating financial and technical analysis software tailored for personal computers. This marks a significant step in bringing advanced trading tools to individual investors and traders. At a time when financial software is primarily used by institutions, CAM’s vision helps democratize access to market analysis by leveraging the growing popularity of PCs. Their work would contribute to the early development of charting and analytical tools that would become standard in technical trading, laying the groundwork for future innovations in financial technology.[54] | United States |

| 1983 | Tool launch | Interactive Data launches what would become eSignal, a groundbreaking charting platform tailored for active traders. Distinguished early on by its use of real-time financial data, eSignal delivers high-quality analytics, news, and decision-support tools through a streaming service—an innovation at the time. Designed for both professionals and individual traders, the platform stands out for its accessibility, requiring little to no coding or technical background. With intuitive charting and simplified data search features, eSignal enables users to interpret complex market information quickly. Its user-friendly interface and real-time capabilities help establish it as a trusted tool in global trading communities.[54] | United States |

| 1984 | Market Infrastructure Development | The New York Stock Exchange launches SuperDOT, an enhanced version of the DOT system that electronically routes orders to trading posts. This marks a key step in the computerization of financial markets. With fully electronic markets emerging, program trading becomes common, involving automated trades of 15 or more stocks worth over $1 million. It supports strategies like index arbitrage between S&P 500 stocks and futures, and portfolio insurance, which mimicks a put option using stock index futures. These strategies would be later implicated in the 1987 stock market crash, though their precise role would remain debated in academic circles.[64] | United States |

| 1984 | Technical indicator development | American economist Richard Roll shows that volatility is affected by market microstructure.[65] | United States |

| 1984 | Tool launch | Computer Asset Management Company (CAM) releases Market Mood Monitor, a software program designed for the IBM PC that marks an important advancement in market analysis tools. It focuses on helping investors interpret and chart overall market conditions, with a particular emphasis on sentiment, momentum, and monetary indicators. The software would later evolve into The Technician, becoming one of the early tools for technical analysis accessible to PC users. This innovation contributes to the growing use of personal computers in financial analysis, empowering individual traders with insights previously available mostly to institutional investors.[54] | United States |

| 1985 | Tool launch | The Market profile graphic is introduced by J. Peter Steidlmayer, a trader at the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). Designed to organize price, time, and volume into a distribution curve, it provides a visual framework for understanding market behavior. The Market Profile displays how prices developed over time, highlighting value areas, points of control, and price acceptance or rejection. It marks a major step in market analysis, blending statistical logic with trading insight, and remains influential in both technical analysis and market microstructure studies today.[66] | United States |

| 1985 (September) | Tool launch | Microsoft launches Excel, a spreadsheet program that transforms data organization and analysis through its grid of rows and columns, enabling calculations, sorting, and chart creation. Widely regarded as one of the most influential tools in finance, its monthly user base is estimated between 700 million and 1.2 billion as of 2025. Despite advances in automation and AI, Excel remains indispensable to finance professionals.[67][68] | |

| 1985 | Theoretical model development | Glosten and Milgrom demonstrate that one source of market volatility arises from the process of liquidity provision. When market makers anticipate potential adverse selection, they widen their bid-ask spreads to manage risk, thereby expanding the range of price fluctuations.[69] | |

| 1985 | Tool launch | MetaStock 1.0 is released for the Apple II+, revolutionizing trading by offering charting and technical analysis tools for stocks, futures, and mutual funds. It works in both real-time and end-of-day versions, calculating financial metrics essential for trading decisions. This software quickly establishes MetaStock as a significant player in the trading industry, providing tools to analyze individual securities and streamline trading strategies.[54] | United States |

| 1985 (December) | Concept development | The term “dead cat bounce” is first used by Financial Times journalists Chris Sherwell and Wong Sulong to describe a brief rebound in the Singaporean and Malaysian stock markets following steep declines during a regional recession. The phrase, based on the saying that “even a dead cat will bounce if it falls from a great height,” refers to a short-lived recovery in a declining asset’s price, also known as a “sucker rally.” Despite the temporary upturn, both economies would continue to fall before recovering in subsequent years.[70][71] | |

| 1987 | Tool launch | TradeStation releases System Writer, a software developed to emphasize the value of backtesting in trading. Recognizing that while past performance doesn't guarantee future results, backtesting can increase the likelihood of success in future trades, System Writer allows users to test their strategies using historical data. This tool enables traders to refine their trading ideas and gain confidence in their strategies by simulating how they would have performed in the past. The ability to backtest gives System Writer an edge in the trading software market, enhancing decision-making for traders.[54] | United States |

| 1897 | Market infrastructure innovation | The NASDAQ introduces the Small Order Execution System (SOES) to automate the handling of small trades, typically up to 1,000 shares. SOES guarantees automatic execution of eligible orders at the best available price, ensuring faster and more reliable fills for retail investors. The system is created partly in response to the 1987 market crash, which exposes weaknesses in manual trade handling during periods of high volatility.[48] | United States |

| 1987 | Indicator development | Peter Martin devises the Ulcer Index, a stock market risk indicator later published with Byron McCann in The Investors Guide to Fidelity Funds. Unlike standard deviation, which treats upward and downward price movements equally, the Ulcer Index focuses on downside volatility, measuring drawdowns that cause stress for long-position investors. Its name reflects the discomfort these declines can cause, though unrelated to actual ulcers. The index helps traders assess risk by highlighting periods of significant price retracement. A later, different version would be developed by Steve Shellans.[72][73] | |

| 1987 (October 19) | Market crash | Black Monday stock market crash is partly attributed to computerized trading strategies known as portfolio insurance. This approach involves automatically shorting stock index futures to hedge against falling equity prices. As markets decline, these algorithms trigger a cascade of sell orders, intensifying the downturn. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunges over 22% in a single day—the largest one-day percentage drop in history. The event exposes the dangers of automated, feedback-driven trading and leads to the introduction of circuit breakers to prevent future systemic collapses.[61] | United States |

| 1988 | Tool launch | Promised Land Technology introduces Future Builders, a groundbreaking network add-in built on Microsoft Excel. Initially designed for performance reporting and generating next-day buy and sell orders, it would later integrate with full trading system strategies. Future Builders introduces an innovative use of 30-year U.S. Treasury bond data to forecast moving average crossovers. This predictive capability is considered revolutionary in the trading community, offering a new level of foresight and automation for traders.[54] | United States |

| 1989 | Concept development | Financial economists Menachem Brenner and Dan Galai propose a “Sigma Index” to measure stock market volatility, laying the groundwork for the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX). Based on their research, the Chicago Board Options Exchange commission Bob Whaley in 1992 to calculate market volatility from S&P 500 options. The VIX, launched soon after, reflects expected 30-day market volatility and is widely known as the “fear index.” It cannot be traded directly but underlies futures, ETFs, and ETNs, with variants like VVIX, VXNSM, VXDSM, and RVXSM.[74][75] | |

| 1989 | Tool launch | Omega Research launches System Writer, a pioneering software that allows traders to create, test, and refine trading strategies using historical data—a process known as backtesting. This innovation marks a major advancement in technical analysis, enabling users to assess the effectiveness of strategies before risking capital. By 1991, the software evolves and is rebranded as TradeStation, integrating more robust analytical features and greater customization.[54] | United States |

| 1990 | Theoretical/model development | Eugene Fama and Kenneth French introduce their influential three-factor model, arguing that stock returns can largely be explained by market risk, size, and value factors. Building on this, Mark Carhart proposes an enhancement in 1997 by adding a fourth factor—momentum—resulting in the Carhart four-factor model. This model acknowledges that stocks with strong past performance tend to continue outperforming in the short term, capturing a critical anomaly in asset pricing. Known in practice as the Monthly Momentum Factor (MOM), it would become a widely adopted tool in mutual fund evaluation and active portfolio management, helping investors better assess risk-adjusted returns. | |

| 1991 | Indicator development | William Blau introduces the True Strength Index (TSI), a technical indicator designed to identify both trend direction and overbought or oversold conditions in financial markets. The TSI is derived from double-smoothed moving averages of a financial instrument’s momentum, aiming to balance momentum’s leading nature with the lagging quality of moving averages. This combination allows the TSI to track price direction more closely and signal market reversals more effectively than either indicator alone. It would be included in most major trading platforms.[76][77][78][79][80][81] | |

| 1991 | Indicator development | Martin J. Pring develops the Know Sure Thing (KST) oscillator, a smoothed price velocity indicator based on the rate of change (ROC). The KST is designed to identify major stock market cycle turning points by emphasizing longer and more dominant time spans, thus capturing primary market swings more effectively. Its underlying principle is that price trends result from multiple overlapping time cycles, and significant reversals occur when several of these cycles shift direction simultaneously.[82][83][84] | |

| 1991 | Indicator development | William Blau develops the Detrended Price Oscillator (DPO), a technical analysis indicator designed to remove long-term price trends using a displaced moving average. By ignoring the most recent price action, the DPO highlights intermediate overbought and oversold levels. It is a type of price oscillator, related to the Percentage Price Oscillator (PPO) and Absolute Price Oscillator (APO), both derived from Gerald Appel’s MACD. While DPO use is less common with signal lines or histograms, these features would be often applied to other price oscillators for enhanced analysis.[85][86][87][88] | |

| 1991 | Indicator introduction | Steve Nison introduces Japanese candlestick charts to the Western world in his book Japanese Candlestick Charting Techniques. Candlestick charts, developed in Japan in the 18th century and likely refined in the late 1800s, display the open, close, high, and low prices of a security within a single period using a thick “body” and wicks. Densely packed with information, they help traders identify short-term trading patterns and potential price movements. Candlestick charts would become widely used in technical analysis of equities, currencies, and derivatives, often alongside tools like Fibonacci analysis.[89][90] | |

| 1992 (July) | Tool launch | MetaStock RT is released, introducing real-time capabilities by receiving live market quotes through Data Broadcasting’s Signal. This advancement marks a major step forward for technical analysis software, enabling traders to analyze and act on market data as it happens. The integration of real-time data allows for faster, more responsive trading strategies, further establishing MetaStock as a key player in the financial software industry.[54] | |

| 1992 | Market Infrastructure | The Financial Information eXchange (FIX) protocol is introduced as a standardized, real-time electronic communications system for trading information. Initially developed by Fidelity Investments and Salomon Brothers, FIX enables seamless electronic exchange of trading data between institutions, brokers, and markets. By reducing reliance on phone calls and manual processes, it significantly improves speed, accuracy, and efficiency in order routing and execution. FIX quickly becomes the global standard for electronic trading communication, supporting equities, derivatives, and other asset classes.[48] | United States |

| 1993 | Index launch | Cboe Global Markets introduces the original Cboe Volatility Index (VIX), designed to measure expected 30-day volatility from at-the-money S&P 100 (OEX) option prices. This early version, later known as the Cboe S&P 100 Volatility Index (VXO), becomes a benchmark for tracking market sentiment. In 2003, Cboe, in collaboration with Goldman Sachs, revises the methodology to use S&P 500 (SPX) options, providing a broader and more accurate measure of expected volatility.[91] | |