Timeline of the American Anti-Vivisection Society

This is a timeline of the American Anti-Vivisection Society, an organization created with the goal of eliminating a number of different procedures done by medical and cosmetic groups in relation to animal cruelty in the United States.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 19th century | The American Anti-Vivisection Society is founded bu Caroline Earle White. Soon after its launch, AAVS proposes its first legislation to restrict vivisection. Other anti-vivisection societies are founded in the century. |

| 20th century | Throughout the twentieth century, raising public awareness continues to play a major role for the Society. Throughout the 1950s, President Owen B. Hunt brings the AAVS message into American living rooms through his regular radio broadcasts, “Have You a Dog?,” and occasional spots on radio and television talk shows into the 1970s. Beginning in the 1970s, the society begins to raise awareness and advocate for alternatives to animal testing by cosmetic companies. In the 1980s, AAVS begins making direct grants for alternatives-driven research.[1] AAVS engages in various humane education programs throughout the twentieth century.[1] |

| 21st century | Today, AAVS campaigns continue to focus on animal experimentation and animal testing, although they have expanded to include a number of other related topics. The End Animal Cloning project, for example, is an attempt to convince federal agencies to end and prohibit the cloning of animals for food production and other purposes, arguing that such practices not only pose threat to public health but also represent a health risk to cloned animals themselves.[2] |

Numerical and visual data

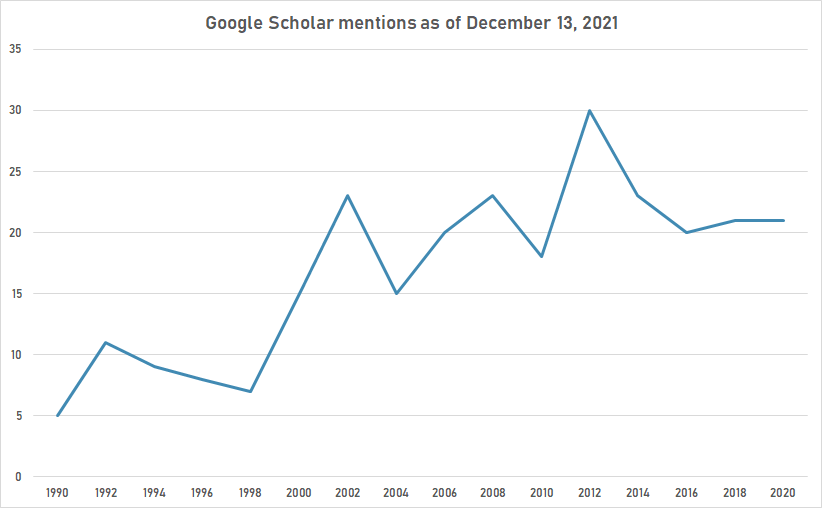

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 13, 2021.

| Year | "American Anti-Vivisection Society" |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 5 |

| 1992 | 11 |

| 1994 | 9 |

| 1996 | 8 |

| 1998 | 7 |

| 2000 | 15 |

| 2002 | 23 |

| 2004 | 15 |

| 2006 | 20 |

| 2008 | 23 |

| 2010 | 18 |

| 2012 | 30 |

| 2014 | 23 |

| 2016 | 20 |

| 2018 | 21 |

| 2020 | 21 |

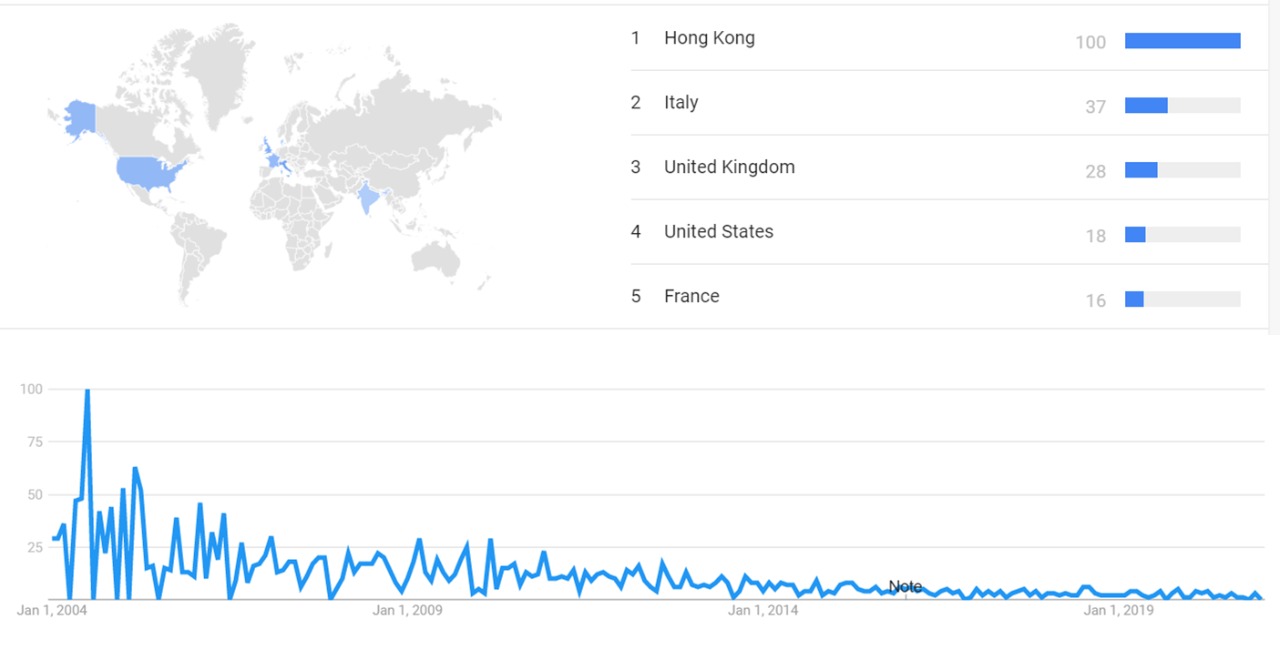

Google trends

The chart below shows Google Trendsdata for American Anti-Vivisection Society (topic), from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[3]

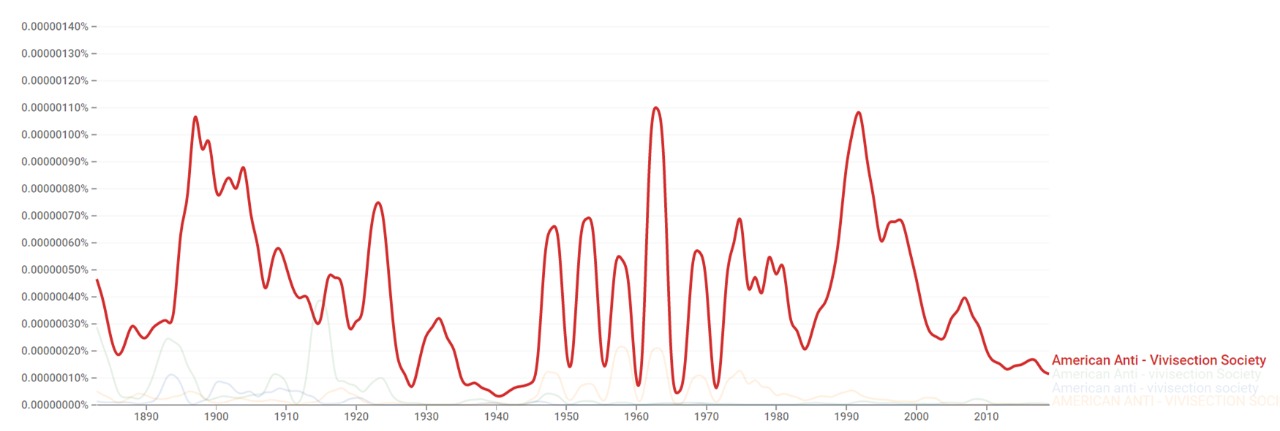

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for American Anti-Vivisection Society, from 1883 to 2019.[4]

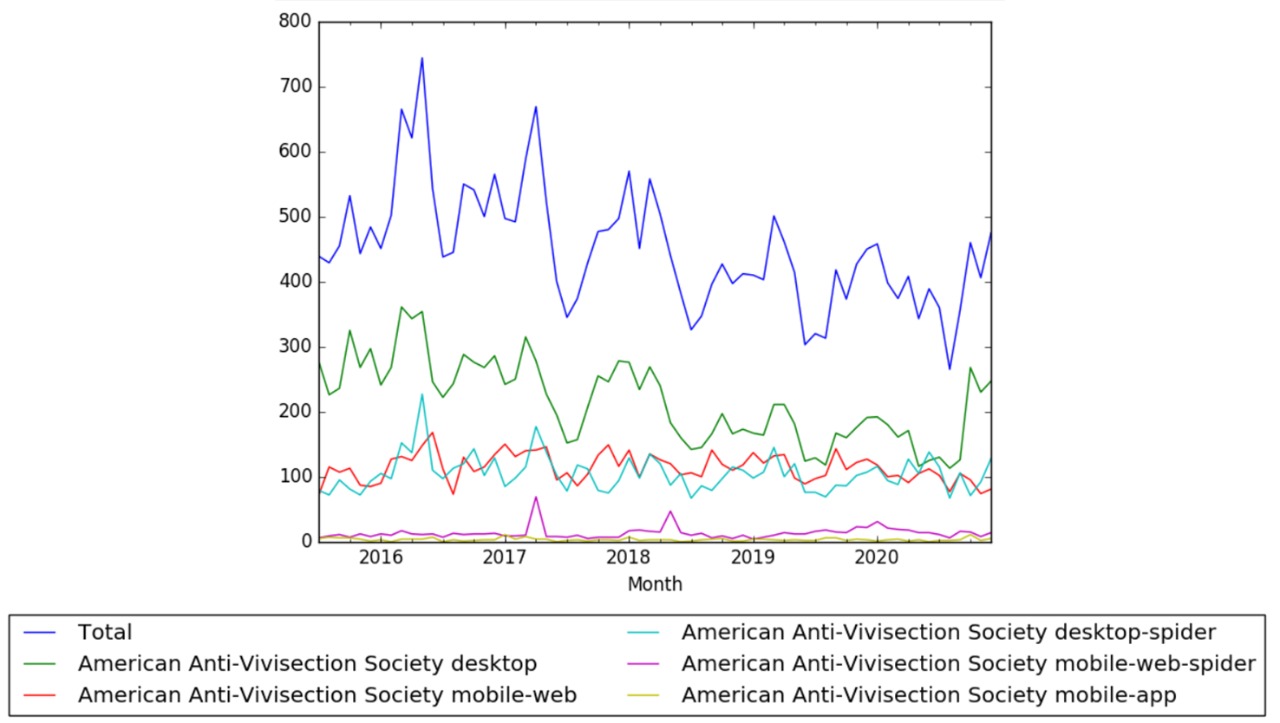

Wikipedia views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article American Anti-Vivisection Society on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to December 2020.[5]

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1866 | Prelude | After reading about the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, American philanthropist Caroline Earle White visits Henry Bergh in New York, and decides to organize a similar effort in Philadelphia. White and her husband begin to secure signatures for a petition supporting the formation of a society to prevent cruelty to animals. Soon, she finds that another Philadelphian, M. Richards Muckle, pursues the same course, and they begin working together. With the assistance of White’s husband, an attorney, they draft a charter with laws, and gain the approval and support of the state legislature.[6] |

| 1860s – 1870s | Animal testing | The first animal experimentation laboratories open in the United States.[1] |

| 1869 (June) | Prelude | At their third meeting, future branch members approve the motion that “one of the objects of this Society shall be, to provide as soon as possible, a Refuge for lost and homeless dogs, where they could be kept until homes could be found them, or they be otherwise disposed of.” The proposal carries unanimously, and the women begin to campaign for control over the taking up and disposal of stray dogs, and for the management of the city pound.[6] |

| 1875 | Organization | The National Anti-Vivisection Society is established in the United Kingdom.[7] AAVS would take this organization as model.[2] |

| 1876 | Policy | The British Parliament passes the first anti-vivisection law, the Cruelty to Animals Act. The result of public outcry against vivisection led by Irish activist Frances Power Cobbe and her Victoria Street Society, the Act is passed by Parliament to regulate the use of animals in scientific research and experimentation in Great Britain.[1] |

| 1883 | Creation | Caroline Earle White founds the American Anti-Vivisection Society (AAVS),[8] with the goal of regulating the use of animals in science and society. [1] The American Anti-Vivisection Society is the first of its kind in the United States.[6] |

| 1885 | Policy | AAVS proposes its first legislation to restrict vivisection. The Bill to Restrict Vivisection is defeated, but it marks the first attempt made by AAVS to seek legislation to end vivisection.[1][2] |

| 1887 | Activism | AAVS initiates a prosecution of pigeon shooters under the 1869 statute, securing a conviction in the lower courts.[6] |

| 1892 | Education | AAVS begins publication of its first magazine, The Journal of Zoophily, printed in conjunction with the Women’s Branch of Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. With education as its mission, Zoophily includes news on vivisection and animal welfare issues and informs members about the society’s latest legislative ventures.[1] |

| 1895 | Organization | The New England Anti-Vivisection Society is founded.[8] |

| 1900 | Legal | AAVS president Dr. Matthew Woods testifies before the United States Congress in favor of the Gallinger Bill, an act to regulate vivisection, based upon the British Cruelty to Animals Act. Though the bill does not pass, the publicity surrounding Woods’ testimony encourages many members of the medical profession to join AAVS.[1] |

| 1903 | Organization | The Vivisection Reform Society is founded.[8] |

| 1907 | Legal | AAVS successfully keeps the United States Congress from altering the 28-Hour Law, which ensures livestock would be fed, watered, and rested at least every 28 hours during transport. Through the efforts of AAVS and the American Humane Association, Congress not only upholds the 28-Hour Law but also works to enforce it.[1] |

| 1908 | Organization | The New York Anti-Vivisection Society is founded.[8] |

| 1910 | AAVS forms an Exhibit Committee, charged with creating a traveling exhibit displaying the instruments and practices involved in animal experimentation. Convinced that viewers could not help but be appalled by vivisection practices, AAVS opens its first exhibit in Philadelphia in the same year, and would be soon sending materials to supporters around the country to display at state fairs and public gatherings.[1] | |

| 1910 | Activism | AAVS and other anti-vivisection organizations reprint an account found in the New York Herald, reporting on the use of vivisection on orphans in an orphanage in Philadelphia[1] |

| 1916 | Notable death | Caroline Earle White dies.[9] |

| 1922 | Education | The Journal of Zoophily changes its name to The Starry Cross.[1] |

| 1926 | The international anti-vivisection convention is held in Philadelphia.[10] | |

| 1927 | Education | AAVS secretary Nina Halvey starts in Philadelphia the Miss B’Kind Animal Protection Club, as an extension of the AAVS’s mission, but with a special focus on humane education. Over the ensuing two decades, Halvey would lead a children’s anti-vivisection society known as the Miss B’Kind Club, with regular meetings at AAVS headquarters, and even hosting parties for children who promise to “be kind to animals now and when I grow up."[11][12][1] |

| 1929 | Organization | The United States National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) is established.[7] |

| 1931 | Recognition | Nina Halvey receives the Humanitarian Award of the Geneva International Bureau for Protection of Animals.[13] |

| 1935 | Education | A total of 15 individual groups of children in the Philadelphia region meet every Saturday at Miss B'Kind Club.[13] |

| 1936 | Campaign | AAVS President Robert R. Logan begins a campaign against trapping by promoting the wearing of fake fur.[1] |

| 1939 | Education | In addition to the Journal of Zoophily (which changed its name to The Starry Cross in 1922, The A-V in 1939, and later the AV Magazine).[1] |

| 1941 | Activism | World’s Fair in New York includes Animal Protection Day, and AAVS President Robert Logan is a featured speaker.[10] |

| 1942 | Education | AAVS holds a three-day Anti-Vivisection School in Philadelphia. Led by then AAVS President Robert R. Logan, students are treated to lectures and practical instruction on the legislative process, public speaking, and running publicity campaigns. The school is held annually for several years. This emphasis on humane education for children and adults continues to be a goal of AAVS today, as seen through the Animalearn program.[1] |

| 1949 | Education | On the World Day for Animals, AAVS is asked to ship 6,500 pieces of specially prepared Miss B'Kind leaflets and 800 posters for distribution in grade schools. This shows significant progress in humane education for AAVS at the time.[13] |

| 1957 | Activism | AAVS protests the launch of Laika into space by the Soviets.[10] |

| 1963 | Campaign | The Help the Huskies campaign is established, providing aid to dogs living in impoverished areas in Alaska.[10] |

| 1966 | Legal | AAVS begins to experience concrete legislative accomplishments in realization of its mission to reduce or eliminate the use of animals in research and testing, with the passage of the Animal Welfare Act.[2] |

| 1972 | Notable death | Nina Halvey dies at the age of 80.[13] |

| 1973 | Legal | AAVS supports Congressman Les Aspin in bringing public attention to the military’s use of beagles in testing poisonous gases and other chemicals. The United States Department of Defense is forced to change this practice when the issue creates the heaviest volume of public letters and outrage the department had ever seen.[1] |

| 1981 | Activism | AAVS provides its first funding to develop alternatives to the Draize rabbit eye test.[10] |

| 1983 | Activism | AAVS helps to fund Suffer the Animals, an exposé documenting the suffering of animals in labs.[10] |

| 1983 | AAVS celebrates its centennial with a symposium entitled "100 Years Against. Cruelty: New Directions through Cooperation."[14] | |

| 1985 | Organization | AAVS and other ten leading societies form a coalition called ProPets (The National Coalition to Protect Our Pets).[15] |

| 2006 | Activism | After a multi-prolonged AAVS campaign, the first company cloning companion animals in the United States closes its doors.[10] |

| 2008 | Activism | AAVS celebrates its 125th Anniversary, rededicating its work to ending animal testing.[10] |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "OUR HISTORY". avs.org. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Newton, David E. Cloning: A Reference Handbook: A Reference Handbook.

- ↑ "American Anti-Vivisection Society". trends.google.com. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "American Anti-Vivisection Society". books.google.com. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ "American Anti-Vivisection Society". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "OUR FOUNDER". aavs.org. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Marquardt, Kathleen; Levine, Herbert M.; Larochelle, Mark. Animalscam: The Beastly Abuse of Human Rights.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 DeMello, Margo. Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-animal Studies.

- ↑ "CAROLINE EARLE WHITE– REFLECTION ON A PIONEER". aavs.org. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 "The History of the American Anti-Vivisection Society". vdocuments.site. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ "Animals in the Archives: American Anti-Vivisection Society". sites.temple.edu. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "Miss B'Kind Club". bekindexhibit.org. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "The History of the American Anti-Vivisection Society". issuu.com. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "Political Animals". digitalcommons.calpoly.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ Orlans, F. Barbara. In the Name of Science: Issues in Responsible Animal Experimentation.