Timeline of the Great Ape Project

This is a timeline of the Great Ape Project (GAP, also Gap Project), an international organization aiming to grant basic moral and legal rights to nonhuman great apes – chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1990s | The Great Ape Project is born in the decade. Founded by Peter Singer and Paola Cavalieri. |

| 2000s | The movement expands to form a global network. The Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes is signed to protect the primates. |

| 2010s | The Great Ape Project continues expansion, with independent bodies in Brazil, Chile, Côte d'Ivoire, Germany, Mexico, Spain and Uruguay and Great Britain. |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | Literature | German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler publishes Intelligenzprüfungen an Menschenaffen (The Mentality of Apes), which analyzes Köhler's experiments and notions of intelligent behavior in chimpanzees.[1] | Germany |

| 1966 | Scientific development | Allen and Beatrice Gardner pioneer the teaching of American Sign Language (ASL) to the chimpanzee Washoe.[2][3][4] | United States |

| 1983 | Literature | American psychologist David Premack publishes The Mind of an Ape, arguing that it is possible to teach language to (non-human) great apes.[5][6] | United States |

| 1988 | Literature | Quarterly international philosophy journal Etica & Animali is launched. It is edited by Paola Cavalieri.[7][8] | Italy |

| 1993 (June 14) | Creation | The Great Ape Project is launched in London by Australian philosopher Peter Singer and Italian philosopher Paola Cavalieri.[9] | United Kingdom |

| 1994 | Literature | The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity is published. Edited by Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer, the book contains contributions from thirty-four authors, including Jane Goodall, Jared Diamond and Richard Dawkins.[10] | |

| 1999 | Policy | New Zealand grants strong protections to five great ape species. Their use is now forbidden in research, testing, or teaching.[11] | New Zealand |

| 1999 | Literature | Paola Cavalieri publishes La Questione Animale (translated The Animal Question: Why Nonhuman Animals Deserve Human Rights).[12] | Italy |

| 2000 | Policy | United States President Bill Clinton signs the CHIMP Act into law, which states that chimpanzees no longer needed for research should not be killed, but moved into sanctuaries, and that the government needs to assume the largest part of funding needed for their lifetime care.[9] | United States |

| 2001 | Program | The Great Apes Survival Project is launched under the auspices of United Nations Environment Programme to safeguard viable populations of great apes and their habitat.[13] | |

| 2002 | Organization | During the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Durban, the Great Apes' Survival Partnership (GRASP) is created to avert danger of extintion of great apes. The project becomes a partnership associating around 100 members: United Nations agencies, governments of the great apes’ range, and representatives of both civil society and the private sector. Together, UNESCO and UNEP are in charge of running GRASP.[13] | South Africa |

| 2005 (September 9) | Treaty | The first intergovernmental meeting on great apes takes place in Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and leads to the signing of the Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes, in which great ape range States commit to do all that is necessary to protect the primates.[13] | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| 2005 | Facility | Chimp Haven opens in Keithville, Louisiana as a non-profit facility. It provides a home for chimpanzees, mostly retired from laboratory research.[14][15] | United States |

| 2006 (July 30) | Expansion | During a meeting held in Madrid, decisions are taken to convert the GAP Project into a more truly international movement, that would better reach the entire world and every country. The most important decisions approved by unanimous vote are: 1) The International Direction Board of GAP Project would be integrated by representatives from the six areas of the world that would run operations: USA/ Canada, Latin America, European Community of Nations, Africa, Asia and Australia/ New Zeland. 2) The Direction Board would have as President, Michele Stump. The philosopher Peter Singer, founder of this Project, would continue to be the Chairman of the Board/Honorary President. 3) The Board of Directors, besides Michele Stump, would include Paco Cuéllar from Madrid, representing the European Community, and Dr. Pedro A. Ynterian, from Sao Paulo, Brazil, representing Latin America. 4) The Board of Directors would hold a yearly meeting, in different regions each time. The Board of Directors would have the responsibility to establish rules, proposals, and basic principles of GAP targets, and through her President would assume positions in front of the world debate about Great Apes. 5) Each ones of six areas where Project is divided would have the responsibility to establish efficient organizations under his or her control, that take all principles of GAP Project to every human existing society.[16] | Spain |

| 2006 | Expansion | GAP Brazil is officially represented by GAP.[17] | Brazil |

| 2007 (February 28) | Policy | The parliament of the Balearic Islands passes the world's first legislation that would effectively grant legal personhood rights to all great apes.[18] | Spain |

| 2007 (December) | Policy | An amendment to the CHIMP Act prohibits use for research ever again on chimpanzees that were moved into sanctuaries.[9][19] | United States |

| 2008 | Policy | The Great Ape Protection Act is introduced to end biomedical research using the remaining chimpanzees in the United States.[9] | United States |

| 2008 (June) | Policy | The Spanish Parliament’s environmental committee approves resolutions urging Spain to comply with the Great Apes Project, voicing its support for the rights of great apes to life and freedom.[20] On 25 June, the Spanish Parliament submits to discussion and approves a resolution by the Izquerda Unida Paliament Comission and Catalunya Party which requests that the Government recoganizes, within four months, GAP Project and its objectives as principals of the Spanish Government and does whatever it is necessary to adapt the country legislation to GAP objectives. The Spanish Parliament is the first in the world declaring endorsement to principals and objectives that consider the great apes as people.[21] | Spain |

| 2008 (July) | Partnership | GAP Project affiliates to the World Society for the Protection of Animals.[22] | |

| 2008 (September) | After a decision by GAP Project International’s Directive Committee, a new board of directors is elected and the world project for protection and defense of the great primates’ rights has Brazil as the new headquarter.[23] | Brazil | |

| 2008 | Facility | Brazil has four sanctuaries affiliated and aligned with GAP’s ideas. The sanctuaries rehome 71 chimpanzees, the majority rescued and recovered after being mistreated at circus or living under inadequate conditions in zoos.[17] | Brazil |

| 2009 (May) | International agency Associated Press produces a news video about GAP Project in Brazil. The video is exhibited at National Geographic website.[24] | Brazil | |

| 2009 (May) | Event | GAP Project Brazil/International participates in the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) workshop, aiming to know better the reality of African sanctuaries and to help in the improvement of the process of spreading information about the rights of great primates.[25] | |

| 2009 (May) | Award | GAP Project Spain is awarded with Chico Mendes Prize, aimed at those who contribute with environment and nature preservation. The prize takes the name of a Brazilian leader, Chico Mendes.[26] | Spain |

| 2009 (July 26) | GAP Project participates in the show “The Big Questions”, chaired by Nicky Campbell and broadcasted on BBC. GAP is invited to debate the theme “Should we give civil rights to apes?” and is represented by philosopher Paula Casal Ribas, vice-president of GAP Spain.[27] | ||

| 2010 (May) | Program | GAP Spain launches Project Free Cetaceans, which intends to extend rights requests to the cetaceans, considered to be the great simians of the oceans.[28] | Spain |

| 2011 (December 15) | A report concluding a study commissioned by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and conducted by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) states that ‘while the chimpanzee has been a valuable animal model in past research, most current use of chimpanzees for biomedical research is unnecessary’.[29] | United States | |

| 2012 (September 21) | Policy | The National Institute of Health announces that 110 chimpanzees owned by the Government of the United States will be retired.[30] | United States |

| 2013 (September 30) | Policy | The CHIMP Act Amendments of 2013 is introduced in the 113th United States Congress.[31] The bill allows the National Institutes of Health to spend a larger portion of their budget on funding the care of retired chimpanzees in chimp sanctuaries.[32] | United States |

| 2014 | Policy | A court in Argentina issues an unprecedented ruling that favors the rights of an orangutan held in captivity. The ape is granted basic rights.[33][34][35][36] | Argentina |

| 2015 (April) | Policy | Justice Barbara Jaffe of New York State Supreme Court orders a writ of habeas corpus to two captive chimpanzees.[37] On April 21, the ruling is amended to strike the words "writ of habeas corpus".[38][39] | United States |

| 2016 (May) | Expansion | Great Ape Project Uruguay is launched.[40] | Uruguay |

| 2017 | Expansion | The International Great Ape Project, consisting already of independent bodies in Brazil, Chile, Côte d'Ivoire, Germany, Mexico, Spain and Uruguay, opens its eighth National Chapter: Great Britain.[41] | United Kingdom |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

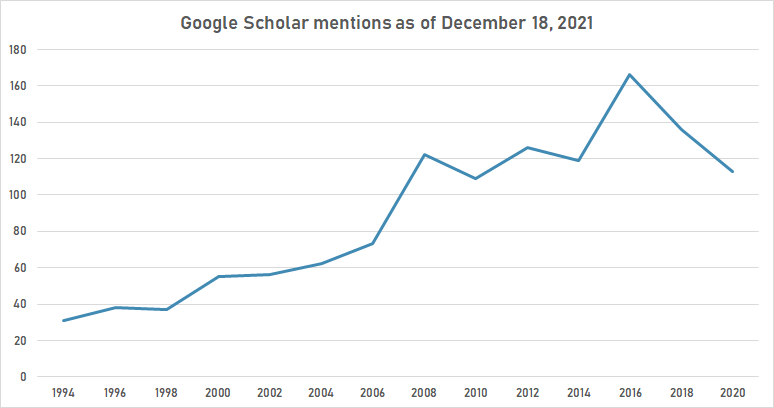

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 18, 2021.

| Year | "Great Ape Project" |

|---|---|

| 1994 | 31 |

| 1996 | 38 |

| 1998 | 37 |

| 2000 | 55 |

| 2002 | 56 |

| 2004 | 62 |

| 2006 | 73 |

| 2008 | 122 |

| 2010 | 109 |

| 2012 | 126 |

| 2014 | 119 |

| 2016 | 166 |

| 2018 | 136 |

| 2020 | 113 |

Google Trends

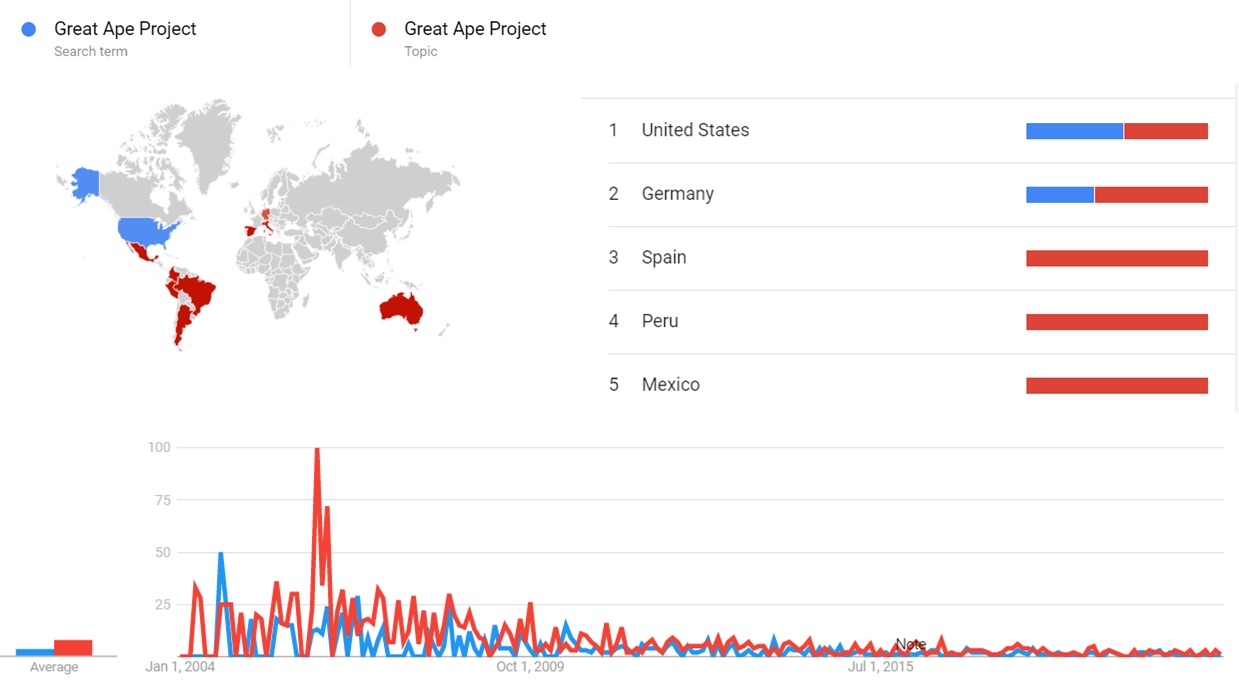

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Great Ape Project (Search term) and Great Ape Project (Topic) from January 2010 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[42]

Google Ngram Viewer

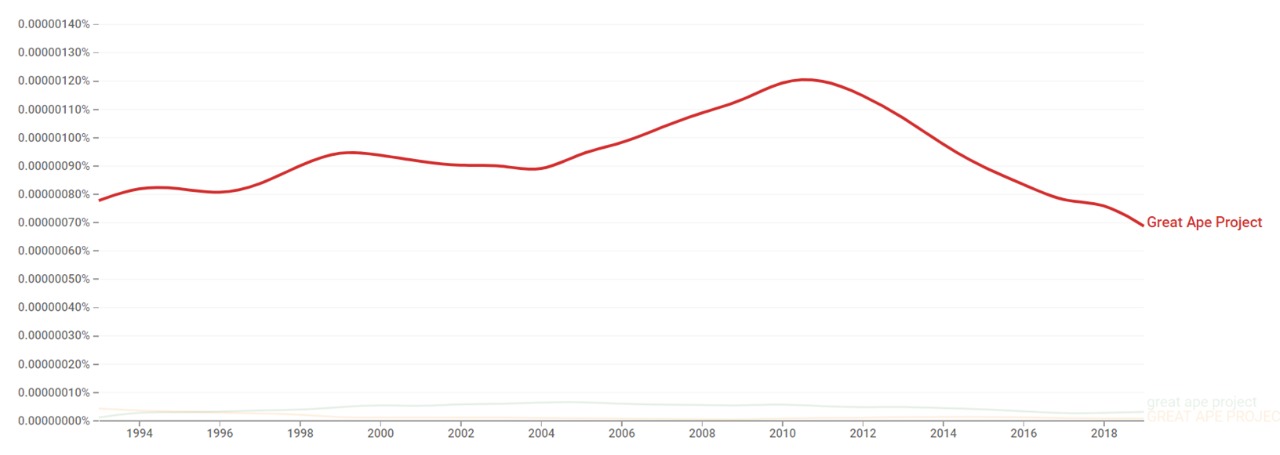

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Great Ape Project from 1993 to 2019.[43]

Wikipedia Views

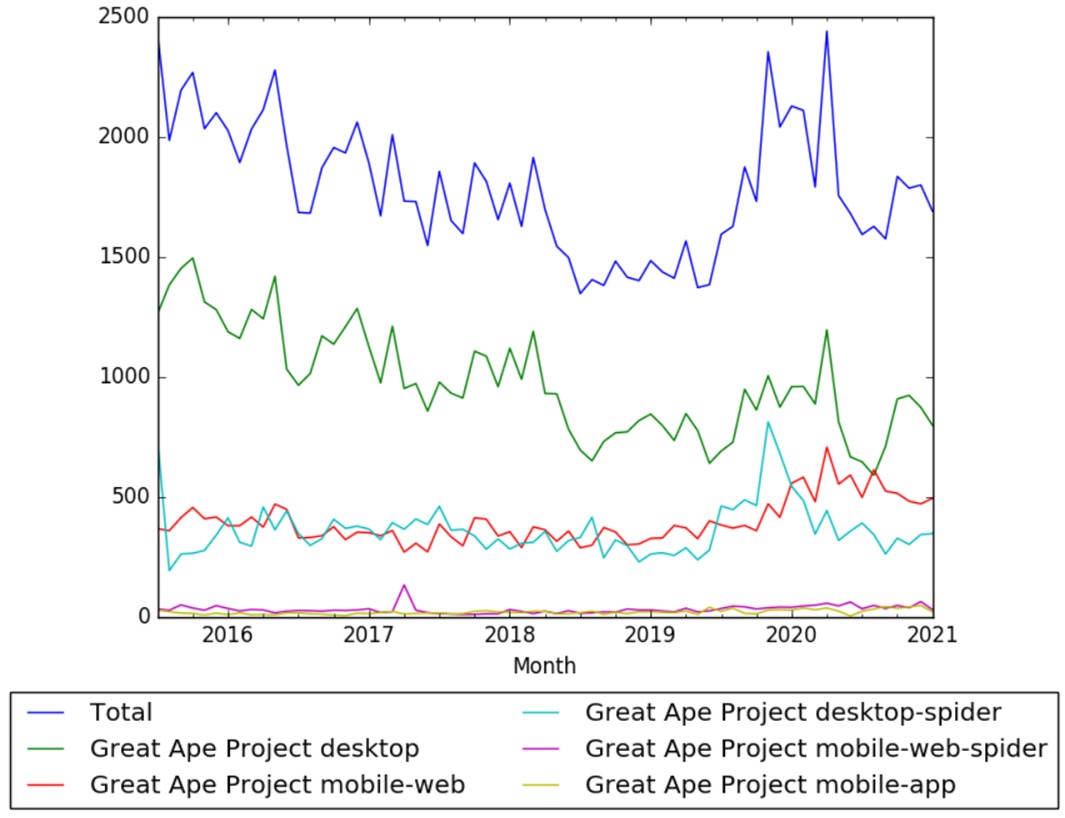

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Great Ape Project on desktop, on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015 to January 2021.[44]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Ruiz, G; Sánchez, N. "Wolfgang Köhler's The Mentality of Apes and the animal psychology of his time". doi:10.1017/sjp.2014.70. PMID 26055050.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "BEATRIX GARDNER (1933 -1995): HER CONTRIBUTIONS TO DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOBIOLOGY". researchgate.net. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Beatrix T. Gardner Dies at 61; Taught Signs to a Chimpanzee". nytimes.com. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees". sunypress.edu. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "The mind of an ape". sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Premack, David; Premack, Ann J. The Mind of an Ape.

- ↑ "Etica & animali". worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "About the author", from Oxford University Press's catalog entry for Cavalieri's book The Animal Question Template:Webarchive.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bekoff, Marc. Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare, 2nd Edition [2 volumes]: Second Edition.

- ↑ "The Great ape project : equality beyond humanity / edited by Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer". trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "A STEP AT A TIME: NEW ZEALAND'S PROGRESS TOWARD HOMINID RIGHTS" BY ROWAN TAYLOR Template:Webarchive

- ↑ Cavalieri, Paola. The Animal Question: Why Nonhuman Animals Deserve Human Rights.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Great apes on brink of extinction Great Apes Survival Partnership (GRASP) Council meeting". unesco.org. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "When chimpanzees leave research labs, they often find a home at Chimp Haven". mnn.com. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "This Sanctuary Helps Former Lab Animals Live the Good Life Read more: http://www.oprah.com/creaturecomfort/chimp-haven-sanctuary-animals-after-the-lab#ixzz5Sh2R3Pzz". oprah.com. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ↑ "GAP PROJECT REORGANIZED". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "History". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ Thomas Rose (2 August 2007). "Going ape over human rights". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2010-02-03. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "The CHIMP Act". releasechimps.org. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "Spanish parliament to extend rights to apes". reuters.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "SPANISH PARLIAMENT SUPPORTS GAP PROJECT AND ITS OBJECTIVES". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP PROJECT AFFILIATES TO WSPA". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "BRAZIL IS THE NEW HEADQUARTER FOR GREAT APE PROJECT – GAP". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Project at National Geographic (video)". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Project participates of PASA Workshop". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Project/ PGS awarded with Chico Mendes Prize". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Project on BBC". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Spain launches Project Free Cetaceans". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ "Chimpanzees in Biomedical and Behavioral Research: Assessing the Necessity". iom.edu. Institute of Medicine. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (21 September 2012). "Government Officials Retire Chimpanzees From Research". NPR. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Chimp Retirement on Hold". the-scientist.com. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "S.1561 - CHIMP Act Amendments of 2013". congress.gov. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Giménez, Emiliano (January 4, 2015). "Argentine orangutan granted unprecedented legal rights". edition.cnn.com. CNN Espanol. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Captive orangutan has human right to freedom, Argentine court rules". reuters.com. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Court in Argentina grants basic rights to orangutan". bbc.com. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Could this landmark animal rights ruling spell the end of zoos?". conservationaction.co.za. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Judge Recognizes Two Chimpanzees as Legal Persons, Grants them Writ of Habeas Corpus". nonhumanrightsproject.org. Nonhuman Rights Project. April 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Judge Barbara Jaffe's amended court order" (PDF). iapps.courts.state.ny.us. New York Supreme Court. April 21, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Judge Orders Stony Brook University to Defend Its Custody of 2 Chimps". www.nytimes.com. New York Times. April 21, 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Nace en Uruguay el Proyecto Gran Simio". projetogap.org.br. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "GAP Affiliated Sanctuaries". greatapeproject.uk. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Great Ape Project". trends.google.com. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ "Great Ape Project". books.google.com. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ "Great Ape Project". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 24 February 2021.