Timeline of the rationalist movement

This is a timeline of the rationalist movement, which refers to a philosophical and intellectual endeavor that emphasizes the use of reason, critical thinking, and evidence-based inquiry to understand and explain the world. Rooted in skepticism of traditional religious and supernatural beliefs, the movement promotes the importance of empirical observation and rational analysis in exploring natural phenomena and societal issues. Rationalism encompasses perspectives that rely on intellectual and deductive reasoning, rather than sensory perception or religious doctrines, as the basis for acquiring knowledge or providing justification.[1] The rationalist movement would evolve over time, beginning with ancient Greek philosophers emphasizing reason and empirical inquiry. Throughout its history, the rationalist movement would advocate for critical thinking, science, and secular values.

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What are some major philosophical milestones in the history of rationalism?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Philosophical development".

- You will see a list of events highlighting key philosophical developments in rationalism, from early Greek thinkers to modern European philosophers. They explore the relationship between reason, faith, and knowledge, shaping logic, ethics, science, and political theory.

- How has rationalism influenced intellectual advancements throughout history?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Intellectual movement".

- You will see a number of key events where rationalist principles shaped intellectual progress, such as Adam Smith's economic theories, Bertrand Russell's contributions to mathematical logic, Noam Chomsky's linguistic theories, and the rise of cognitive science.

- What are some significant literary works that have contributed to the development of rationalist thought?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Literature".

- You will see a list of significant literary works that have shaped rationalist thought, including influential books by philosophers and scientists. These works cover topics such as logical positivism, skepticism, libertarianism, cognitive biases, and scientific thinking, spanning multiple decades.

- How has the rationalist movement influenced political thought?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Political event".

- You will see a number of political events shaped by Enlightenment and rationalist ideals, highlighting their influence on governance, individual rights, and democratic principles.

- How has rationalist thought influenced technological advancements throughout history?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Technological impact".

- You will see an overview of key innovations and figures influenced by rationalist principles. Highlights include major advancements in computing, artificial intelligence, cybernetics, and data science, as well as the role of logical reasoning in shaping modern technology.

- What are some key organizations associated with the rationalist movement?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Organization".

- You will see a number of organizations linked to the rationalist movement, including their founding years, locations, and missions. The summaries highlight their roles in promoting secularism, scientific inquiry, critical thinking, AI safety, humanism, and skepticism, along with key figures and historical influence.

- What are some key milestones in the history of the rationalist online community?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the group of rows with value "Online community".

- You will see a chronology outlining the evolution of the rationalist online community, starting with early discussions on Usenet and internet forums in the 1990s.

Other events are described under the following types: "Conference", "Scientific and ethical development".

Big picture

| Period | Timeframe | Key characteristics | Notable Figures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century BCE – 16th century CE | Foundations of Rational Thought | Rationalist thought originates in Ancient Greece, with Plato and Aristotle establishing reason as the primary path to knowledge. Plato’s Theory of Forms suggests that abstract ideas are more real than physical objects, while Aristotle’s logic and empirical observations lay the groundwork for scientific thought. The Socratic method promotes critical inquiry and dialectical reasoning. In the Islamic Golden Age, Avicenna and Averroes integrate Aristotelian rationalism with Islamic theology, preserving and expanding classical knowledge. In medieval Europe, Thomas Aquinas attempts to reconcile reason with Christian doctrine through Scholasticism. The Renaissance (14th–16th centuries) revives classical rationalism, emphasizing critical thinking, systematic reasoning, and empirical observation. Thinkers like Leonardo da Vinci and Copernicus advance rational inquiry, paving the way for the Scientific Revolution, which would soon prioritize structured logic and systematic experimentation as means of understanding the world. | Plato, Aristotle, Avicenna, Averroes, Aquinas, Descartes (early work) |

| 17th–19th centuries | Rationalist Age | The Scientific Revolution (17th century) marks the emergence of rationalism as a dominant force in intellectual life. René Descartes, regarded as the father of modern rationalism, develops deductive reasoning, famously asserting Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am). Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz further argue that reason, rather than sensory experience, is the foundation of knowledge. During the Enlightenment (18th century), rationalism extends into ethics, governance, and political philosophy. Thinkers like Voltaire, Diderot, and Kant advocate for reason-based governance, religious tolerance, and human rights, influencing major revolutions. The 19th century sees rationalism evolve into scientific positivism, with Auguste Comte proposing that human knowledge progresses through empirical science. Meanwhile, advances in mathematical logic by Gottlob Frege and early work in psychology reflect the increasing influence of rationalist principles across disciplines. This period establishes rationalism as the foundation of modern science, secularism, and analytical philosophy. | Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Voltaire, Kant, Comte, Frege |

| 20th century – present | Modern and applied rationalism | Rationalism expands beyond philosophy into mathematical logic, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, and decision theory. The Vienna Circle champions logical positivism, arguing that meaningful statements must be verifiable through logic or empirical evidence.[2] Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein[3] refine rationalist methodologies, influencing analytic philosophy. In the late 20th and 21st centuries, rationalist thought shapes advancements in AI, neuroscience, and decision theory. The rise of Effective Altruism and LessWrong promotes rationalist principles in ethics and global problem-solving. Thinkers like Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky apply rationality to existential risks, AI safety, and transhumanism. Rationalist principles also influence secular ethics and public policy, with figures like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris advocating for reason-based discourse. Today, rationalist movements continue to impact fields ranging from probability theory to Bayesian epistemology, driving efforts to use logic and data-driven reasoning for global decision-making. | Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Noam Chomsky, Nick Bostrom, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris |

Summary by century

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 5th century BCE | Birth of rationalism | Rationalist thought emerges in Ancient Greece. Socrates develops the Socratic method, emphasizing reasoned dialogue. Plato introduces the Theory of Forms, asserting that reason leads to true knowledge, while Aristotle lays the foundations of logic and empirical observation. Mathematics, particularly in Pythagorean philosophy, is seen as a key to understanding reality. Rational thought is applied in ethics, politics, and metaphysics, establishing a framework that would influence Western philosophy for centuries. |

| 4th–3rd centuries BCE | Rise of logical systems | Aristotle’s influence dominates, as he refines formal logic (syllogism) and promotes systematic observation of nature.[4] The Hellenistic schools, including Stoicism and Epicureanism, advocate for rational control over emotions and the pursuit of knowledge through logical reasoning. The Library of Alexandria becomes a center of scientific inquiry and rationalist scholarship, with figures like Euclid[5] (geometry) and Archimedes[6] (mechanics) advancing mathematical rationalism. |

| 2nd century BCE – 5th century CE | Decline of classical rationalism | The Roman Empire inherits Greek rationalism, with Cicero and Seneca promoting Stoic rational thought. However, rationalism declines with the fall of Rome.[7] Meanwhile, in India and China, Buddhist logic[8] and Confucian rationalism[9] develop independently, emphasizing structured reasoning and ethical decision-making. As Christianity spreads, Neoplatonism (Plotinus) attempts to merge rational thought with spirituality. The decline of classical rationalism accelerates with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. |

| 17th century | Age of Rationalism | The Scientific Revolution and Age of Enlightenment mark the formal emergence of rationalism.[10] Thinkers such as René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz develop rationalist philosophy, arguing that knowledge is derived primarily from reason rather than experience.[11] Descartes’ Cogito, ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am") becomes a foundational statement of rationalist epistemology. Spinoza presents a deterministic and monistic view of the universe in Ethics, while Leibniz introduces the idea of innate ideas and a rational order to reality.[12] This era witnesses the rise of deductive reasoning as a dominant epistemological method. |

| 18th century | Intellectual movement | The Enlightenment sees rationalism applied to political philosophy, ethics, and science. Thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, though attempting a synthesis between rationalism and empiricism, emphasize the role of reason in understanding moral law (Critique of Pure Reason, 1781). The French Enlightenment, led by Voltaire, Denis Diderot, and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, promotes rational inquiry and the rejection of superstition. The publication of Encyclopédie (1751) aims to organize human knowledge systematically. Rationalist principles influence political revolutions, including the American (1776) and French (1789) Revolutions, advocating for reason-based governance and individual rights. |

| 19th century | Social Movement | Rationalism faces challenges from Romanticism and Idealism, but it remains influential in science and mathematics. Auguste Comte develops positivism, advocating for a rational, empirical approach to knowledge. In mathematics, Georg Cantor’s work on set theory and Frege’s advancements in logic contribute to the formalization of rationalist methodologies. Meanwhile, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution (1859) applies rational inquiry to biological science, challenging religious orthodoxy. Rationalism also fuels secularism and atheism, as seen in the works of Friedrich Nietzsche and early humanist movements, emphasizing reason over faith in explaining human existence and ethics. |

| 20th century | Analytic rationalism | Rationalism finds expression in logical positivism, particularly through the Vienna Circle (Carnap, Schlick, Neurath), advocating for scientific reasoning and verifiable statements. Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead develop mathematical logic (Principia Mathematica, 1910–1913), while Ludwig Wittgenstein explores the limits of rational language.[13] In cognitive science, Noam Chomsky's theory of universal grammar suggests innate rational structures in human thought.[14] Meanwhile, secular humanism grows, emphasizing rational ethics and scientific progress. The rise of artificial intelligence and computational logic reinforces rationalist perspectives, as reasoning becomes integral to technological advancements. |

| 21st century | Applied rationalism | Rationalism continues to shape science, philosophy, and technology. The Effective Altruism and LessWrong movements, led by figures like Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nick Bostrom, apply rationalist principles to ethics and decision-making. The rise of artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and neuroscience further examines the nature of human reasoning. Atheism and secularism gain traction, particularly through figures like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, who argue for a rationalist critique of religion. Rationalist principles influence policy-making, economic models, and transhumanist thought, advocating for a future guided by data, logic, and long-termism. |

Full timeline

Inclusion criteria

We incude:

- Major philosophical movements, key figures and their contributions, foundational texts and their impact, the development of logic, epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics, as well as their influence on later philosophical traditions.

- Milestone publications promoting rationalist philosophy, logic, skepticism, scientific reasoning, critical thinking, and secularism, especially those challenging dogma, superstition, or irrational beliefs.

- Significant organizations promoting rationalism, secularism, scientific inquiry, humanism, skepticism, and AI safety, such as the Rationalist Association (1885), Humanists International (1952), CSICOP/CSI (1976), MIRI (2000), and CFAR (2012).

- Key scientific advancements supporting rationalism, including Galileo's telescope improvements (1609), Newton's laws of motion (1687), Darwin's theory of evolution (1859), Haeckel's materialism and evolutionary thought (1871), Wundt's experimental psychology (1879), Einstein's theory of special relativity (1905), developments in logic and AI ethics (1960s, 2020).

- Major historical political events that directly align with Enlightenment ideals, such as advocating for individual rights, democracy, reason, separation of powers, or challenging traditional authority, monarchies, and religious discrimination.

We exclude:

- Events lacking a clear link to rationalist philosophy, focusing on economics, political theory, or linguistics without emphasizing reason, logic, or epistemology.

- Minor figures, regional schools, smaller or less globally influential groups.

- Advancements outside the scope of rationalism or scientific inquiry, as well as those not directly related to the rationalist movement's core values.

Timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6th–4th century BCE | Philosophical development | Early rationalist thought begins with pre-Socratic philosophers, who explore diverse topics beyond physics, including ethics, perception, mathematics, and causality. Many also study embryology and the human body, highlighting connections between philosophy and medicine. The discovery of texts like the Derveni Papyrus suggests their ideas are widely known, not limited to a small intellectual elite. Their inquiries into matter, form, and explanation lay the foundation for later philosophical traditions, influencing Plato, Aristotle, and Western thought as a whole. These thinkers help shape key philosophical concerns that continue to be explored today.[15] | Ancient Greece |

| 5th–4th century BCE | Philosophical development | Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle develop foundational principles of logic and epistemology. As key figures in Western philosophy, they shape ethics, knowledge, and metaphysics. Socrates emphasizes questioning through the Socratic method, influencing Plato, who formulates the theory of forms and political philosophy. Plato founds the Academy, where Aristotle studies before establishing his own school, the Lyceum. Aristotle rejects Plato’s idealism, advocating empiricism and logic. His works on ethics, politics, and metaphysics remain influential. Their collective ideas continue to shape modern philosophy, science, and education, forming the intellectual backbone of Western thought. Understanding their contributions is essential for studying ancient and contemporary philosophy.[16][17] | Ancient Greece |

| 3rd century BCE | Philosophical development | The rise of Stoicism and Epicureanism highlights reason as essential for achieving a fulfilling life. Both philosophies advocate rational thought as a means to navigate uncertainty, cultivate self-sufficiency, and attain inner peace. Stoics use reason to align with the universe’s natural order, regulate emotions, and fulfill social duties, while Epicureans apply reason to distinguish between necessary and excessive desires, overcoming fear through understanding nature. Both reject irrational fears and emphasize self-reflection as key to wisdom and happiness. Despite their differences, they share the belief that a reasoned approach to life fosters resilience, ethical living, and freedom from unnecessary suffering.[18] | Ancient Greece |

| 20 BCE – c. 50 CE | Philosophical development | Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria promotes the integration of Greek philosophy, especially Platonism, with Jewish religious teachings. His major achievement is using allegorical interpretations of scripture to reconcile the two systems of thought. Philo emphasizes a rational approach to theology, applying reason and logic to understand divine concepts, which leads to a more philosophical interpretation of Jewish beliefs. He introduces the concept of the "Logos," a divine intermediary between God and the world, which would later influence early Christian theology, making his work integral to the development of Christian thought.[19][20][21][22] | Alexandria, Egypt |

| 354 – 430 | Philosophical development | Berber theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo emphasizes the importance of reason in understanding faith and the universe, asserting that "faith seeks understanding." He believes that while faith precedes reason, it should be supported and illuminated by rational thought, using one's God-given intellect to explore and comprehend both faith and the world. Augustine argues that there is no conflict between faith and reason, as both are divine gifts meant to work together. He states, "unless you believe, you will not understand," emphasizing that faith is the first step in gaining deeper understanding, with reason serving as a tool to interpret the truths revealed by faith.[23][24][25][26][27] | Roman Empire (modern-day Algeria) |

| 7th century | Intellectual movement | The Muslim conquest of Persia leads to the integration of cities where Greek philosophy, preserved by banished Greek philosophers and Syriac Nestorians, survive. The Muslim empire supports the preservation and expansion of Greek intellectual traditions, especially through the Arabic translation movement in Baghdad. The House of Wisdom, founded by Harun and later expanded by Mamun, becomes a key institution for translating Greek scientific and philosophical works into Arabic. This movement allows medieval Muslim philosophers access to Greek texts, fostering their reasoned approach to philosophy.[28] | Islamic World |

| 980–1037 | Philosophical development | Persian polymath Avicenna (Ibn Sina) integrates Greek rationalism with Islamic thought, arguing that reason and faith can coexist. His synthesis of Greek philosophy and Islamic theology influences both Islamic and medieval European scholars, including Thomas Aquinas. Avicenna’s work marks the peak of the Hellenic tradition in the Islamic world. He founds Avicennian logic and Avicennism, introduces the concept of inertia in physics (precursor to Newton’s first law), and contributes to geology with ideas on uniformitarianism and the law of superposition, earning him the title "father of geology."[29] [30] [31] [32] | Persia (modern-day Iran) |

| 12th–13th century | Philosophical development | Scholasticism emerges in medieval Europe as a way to reconcile Christian theology with classical philosophy, especially Aristotle's works, through reason and logical analysis. It aims to harmonize faith and reason, using dialectical reasoning to resolve contradictions and support religious truths. This intellectual movement shapes medieval thought, with key figures like Thomas Aquinas emphasizing the compatibility of faith and reason. Scholasticism influences theology, education, and law, establishing universities as centers of learning. It contributes to a broader intellectual culture that values reasoned argument, which would have a significant impact on medieval society, law, and politics.[33][34] | Europe |

| 14th–16th century | Intellectual movement | The Renaissance revives classical rationalist ideas, drawing inspiration from Ancient Greek and Roman thought. This period emphasizes humanism, where reason and intellectual exploration are celebrated. Thinkers like Leonardo da Vinci and Nicolaus Copernicus seek to reconcile scientific inquiry with classical ideas, reintroducing the belief in objective observation and logic. The Renaissance fosters a cultural and intellectual awakening, laying the groundwork for the Enlightenment, which would further emphasize reason, scientific discovery, and the scientific method. This revival of classical rationalism helps shape the development of modern Western philosophy, with a focus on logic, evidence, and critical thinking.[35] | Europe |

| 1609 | Scientific advancement | Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei improves the telescope, enabling groundbreaking observations of the night sky. His enhancements allow detailed views of the Moon's surface, revealing mountains and craters, challenging the belief in a perfect celestial sphere. Galileo's most significant discovery is the four largest moons of Jupiter—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—which contradict the Earth-centered geocentric model. These findings directly oppose the Aristotelian view of a perfect, unchanging universe, supporting the Copernican heliocentric model and marking a pivotal shift in cosmology. Galileo's work lays the foundation for modern astronomy and the scientific revolution.[36][37][38][39] | Italy |

| 1637 | Philosophical development | René Descartes publishes Discourse on the Method, a foundational work in modern philosophy and science. In it, Descartes outlines a method based on skepticism and reason to understand the natural world. The treatise is famous for the quote "I think, therefore I am" (" je pense, donc je suis"). Descartes’s method includes four key rules: only accept clear and evident truths, break problems into parts, begin with simpler knowledge, and carefully check work for errors. The full title is Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences.[40][41] | France |

| 1641 | Philosophical development | Descartes publishes Meditations on First Philosophy, a seminal philosophical work that introduces metaphysical dualism. Divided into six meditations, Descartes questions the certainty of beliefs and argues for the existence of God and the distinction between mind and body. He establishes a rational foundation for human knowledge with the famous idea "I think, therefore I am." The treatise is a cornerstone of modern Western philosophy, influencing Continental thought, metaphysics, and philosophy of religion. Written in Latin and dedicated to the Jesuit professors at the Sorbonne, it be later translated into French in 1647.[40] | France |

| 1651 | Philosophical development | English philosopher Thomas Hobbes publishes Leviathan, a foundational work of Western political philosophy, introducing social contract theory. Hobbes argues that, without government, humans exist in a violent "state of nature" where life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." To ensure order, people surrender some freedoms to an absolute sovereign. His ideas would influence European liberal thought, including individual rights, natural equality, and the necessity of political power based on consent. Hobbes would also contribute to classical scholarship, translating The Iliad, The Odyssey, and The History of the Peloponnesian War into English.[42] [43] [44] | England |

| 1674 | Philosophical development | Nicolas Malebranche publishes The Search After Truth, a foundational work in which he argues that humans perceive ideas through God, blending Augustinian and Cartesian thought. A French Oratorian priest and rationalist philosopher, Malebranche promotes doctrines such as occasionalism and vision in God. His theories, including "intelligible extension" and God's use of general over particular volitions, would spark intense debate, especially with Antoine Arnauld. Their conflict would lead to Malebranche’s Treatise on Nature and Grace being placed on the Church’s Index of Prohibited Books in 1690. Despite opposition, Malebranche would remain a major figure in 17th-century metaphysics and theology.[45] [46] [47] [48] [49] | France |

| 1677 | Philosophical development | Baruch Spinoza publishes Ethics, which presents a philosophical system based on monism and determinism, arguing that everything is part of a single, infinite substance—"God or Nature." Spinoza rejects free will, asserting that all events follow strict natural laws. Spinoza emphasizes rationalism, believing reason is the key to true knowledge. Ethically, he advocates for living in harmony with reason to attain the "intellectual love of God," understanding one’s place in the natural order. His work challenges traditional religious and philosophical views, laying the foundation for modern rationalist and pantheistic thought.[50] [51] [52] | Netherlands |

| 1686 | Philosophical development | G.W. Leibniz publishes Discourse on Metaphysics, where he introduces the principle of the identity of indiscernibles, stating that no two distinct objects can have exactly the same properties. He also publishes Brevis Demonstratio Erroris Memorabilis Cartesii et Aliorum Circa Legem Naturae, a work that critiques Descartes' laws of nature and presents Leibniz's own views on dynamics. Additionally, Leibniz continues his philosophical and mathematical developments, contributing to his theory of knowledge, where he argues that human ideas are analogously related to God's ideas. This year marks significant advancements in his metaphysical and scientific theories.[53] | Germany |

| 1687 | Scientific advancement | Isaac Newton publishes Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, a groundbreaking work establishing the laws of motion and the science of dynamics, which revolutionizes both Earth and space sciences. Principia challenges the previous divide between Earth's and celestial laws, asserting their universality. The book's first edition, with annotations by Newton and his peers, becomes one of the most influential texts in science.[54] | England |

| 1689 | Philosophical development | English philosopher John Locke publishes An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, in which he argues that all knowledge comes from sensory experience, rejecting the idea of innate ideas. Locke introduces the concept of tabula rasa, describing the mind at birth as a "blank slate" shaped by experience. Locke refutes the notion of pre-existing knowledge, challenging prevailing philosophical views. His emphasis on empirical reasoning establishes him as a key figure in empiricism, influencing later thinkers such as David Hume and John Stuart Mill. The essay lays the groundwork for modern theories of knowledge, psychology, and education, shaping Enlightenment thought and the development of liberal philosophy.[55] [56] | England |

| 1739 | Philosophical development | David Hume publishes A Treatise of Human Nature, challenging rationalist metaphysics. In this work, Hume critically examines skepticism and questions the role of reason in grounding the foundational beliefs that support science and morality. He argues that while reason alone cannot justify these beliefs, humans are psychologically compelled to accept them. The Treatise’s complex ideas would give rise to a variety of interpretations, influencing movements such as positivism, empiricism, and virtue ethics. Hume’s exploration of skepticism, causality, and human nature continues to shape philosophical discourse, with his theories on skeptical realism, causality, and human action emerging as central themes that are still widely debated by scholars.[57] | Scotland |

| 1748 | Political Event | French judge political philosopher Montesquieu publishes The Spirit of the Laws, a pivotal work in the European Enlightenment that would profoundly shape political thought. The book analyzes government institutions, argues that government type depends on circumstances, and advocates for a constitutional system with separation of powers. It also calls for the abolition of slavery and religious persecution, and proposes more humane laws. Initially published anonymously, it would be translated widely and condemned by the Catholic Church. Influencing figures like Catherine the Great and the American Founding Fathers, it would pioneer comparative law and advanced political thought for centuries.[58][59] | France |

| 1751 | Intellectual movement | The Encyclopédie is first published under the direction of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, embodying the rationalist ideals of the Enlightenment. Published until 1780 in 35 volumes, it is the first systematic effort to document all human knowledge, aiming to provide a practical reference for tradespeople. The work is organized into three main categories—memory, reason, and imagination—and presents knowledge in a didactic, schematic format that emphasizes reason and the scientific method. The encyclopédistes, the contributors, seek to explore the world through intellectual exchange and scientific inquiry. Diderot is a philosopher and writer, while d'Alembert is a mathematician and philosopher.[60][61][62] | France |

| 1762 | Philosophical development | Jean-Jacques Rousseau publishes The Social Contract, in which he argues for political authority based on the general will of the people. The book introduces key ideas, such as the social contract—where people sacrifice some independence for political liberty—and the general will, which aims for the common good. Rousseau emphasizes freedom and equality as natural rights, achievable through democracy, and proposes civil religion to promote virtues like courage and patriotism. The Social Contract would inspire the 1789 French Revolution and anti-feudal movements, and its ideas about freedom and equality would continue to influence political thought.[63][64][65][66] | France |

| 1765 | Philosophical development | French writer Voltaire publishes Questions sur les Miracles, a series of twenty anonymous pamphlets criticizing belief in religious miracles and defending reason, free expression, and democracy. Written in response to Protestant pastor David Claparède, Voltaire uses satire to oppose the idea that God would violate natural laws for specific events. He mocks figures like biologist John Needham and philosopher Rousseau, and criticizes religious authorities in Geneva. One famous passage argues that those who believe absurdities may be led to commit injustices. Voltaire viewes miracles as moral allegories, not literal occurrences.[67][68][69][70][71] | France |

| 1776 | Political event | The American Declaration of Independence is adopted. It is shaped by Enlightenment ideals emphasizing reason, individual rights, and scientific analysis. Written by Thomas Jefferson, it proclaims that all people are born with the unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, drafted earlier in 1776, affirms that all individuals are born free and independent. Enlightenment principles also influences early American state governments, which focus on empowering citizens. France's support for the American Revolution is motivated by its alignment with Enlightenment ideals, which also inspires subsequent revolutions like the French Revolution.[72][73][74][75] | United States |

| 1776 | Intellectual movement | Adam Smith publishes The Wealth of Nations, a foundational work in economic thought. Smith argues that competition and the division of labor foster prosperity and stability. He introduces the concept of the "invisible hand," suggesting that individuals pursuing self-interest in competitive markets inadvertently benefit society. Smith also believes the government should focus on protecting borders, enforcing laws, and supporting public works. He emphasizes that a nation's wealth is tied to the well-being of its citizens. Smith, a key figure in the Scottish Enlightenment and classical liberalism, also writes The Theory of Moral Sentiments.[76][77][78] | Scotland |

| 1781 | Philosophical development | Immanuel Kant publishes Critique of Pure Reason, seeking to reconcile rationalism and empiricism. Kant proposes that knowledge is not derived solely from experience or reason but from a combination of both, filtered through our cognitive faculties. His central idea, "transcendental idealism", argues that the mind actively constructs reality by applying a priori categories, such as space and time, to sensory data. Kant also claims that while we can know the phenomenal world (our perception of reality), we can never access the noumenon (the world as it truly is) due to the limits of human cognition.[79][80][81][82][83] | Germany |

| 1785 | Philosophical development | Immanuel Kant publishes Metaphysics of Morals, a foundational work in moral philosophy. In this book, Kant seeks to establish the categorical imperative as the supreme principle of morality. He argues that humans are ends in themselves and should never be treated merely as means. He also emphasizes that universal and unconditional moral duties stem from human autonomy and self-governance. This work lays the foundation for his later ethical writings, including Critique of Practical Reason and The Metaphysics of Morals, further developing his deontological ethical framework.[84][85] | Germany |

| 1789 | Political event | The French Revolution begins on July 14, with the storming of the Bastille. It is driven by Enlightenment ideals that challenge traditional authority, social hierarchies, and absolute monarchy. Philosophers like Voltaire and Rousseau promote reason, individual rights, and democracy, inspiring revolutionaries. Social inequalities, economic hardship, and political discontent fuel public anger. The Revolution leads to a radical political transformation, marked by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which emphasizes equality before the law. Key causes include economic inequality, social injustice, and the power struggle between the nobility and bourgeoisie.[86][87][88][89] | France |

| 1794–1795 | Philosophical development | Johann Gottlieb Fichte publishes Foundations of the Science of Knowledge (Grundlage der gesammten Wissenschaftslehre), further developing German Idealism that builds on rationalist principles. The book is based on lectures he delivered as a professor at the University of Jena. In this work, Fichte establishes his system of transcendental philosophy, outlining his views on the fundamental principles of human cognition. His philosophy centers on the concept of subjectivity, or the "pure I," which he argues is self-positing and forms the foundation of all knowledge and experience. Fichte's ideas are a key part of post-Kantian idealism.[90][91][92][93] | Germany |

| 1812–1816 | Philosophical development | German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel publishes Science of Logic, contributing to rationalist ideas about dialectical reasoning and the development of thought. The book outlines his dialectical vision of logic. It is a two-volume work that integrates traditional Aristotelian syllogism with Hegel's concept of dialectical metaphysics. Hegel argues that thought and being are an active unity, with "totality" as a key concept—an overarching system that includes and transcends previous stages of development. Known also as "Greater Logic", it is distinct from Hegel’s "Lesser Logic" found in his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences.[94][95] | Germany |

| 1830-1842 | Philosophical development | French philosopher Auguste Comte publishes his Course of Positive Philosophy, which outlines his doctrine of positivism and is considered foundational to modern sociology. In the first three volumes, Comte surveys the established physical sciences—mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, and biology—while the final two volumes argue for the emergence of a new “queen science”: sociology. He stresses the interdependence of theory and observation, proposing that social sciences can only mature once simpler sciences have developed. Comte believes social harmony requires intellectual unity through scientific understanding. Harriet Martineau’s 1853 translation would help spread these ideas, which he would further elaborate in A General View of Positivism (1865).[96][97][98] | France |

| 1859 | Scientific advancement | English naturalist, geologist, and biologist Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species, introducing the theory of evolution by natural selection, which becomes the foundation of evolutionary biology. The book provides evidence that life evolved from a common ancestor through a branching pattern, supported by Darwin's observations during his HMS Beagle voyage in the 1830s. It shows that behavior evolves through natural selection and lays the groundwork for anthropology. The book challenges the idea of divine creation, and Darwin's insights into natural selection leads to significant scientific advancements, including his study of finches on the Galápagos Islands.[99][100][101] | England |

| 1871 | Political event | The Universities Tests Act 1871 ends religious discrimination at Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham universities by abolishing religious tests for admissions and employment, except in divinity. It ensures that individuals of all faiths can access university education, preventing institutions from requiring students or staff to adhere to any religious beliefs, attend specific worship services, or belong to a particular denomination. The act is passed to broaden access to higher education while preserving religious instruction. Its impact extends to universities beyond England, influencing institutions like Trinity College Dublin in 1873 and Scottish universities in 1889.[102] | England |

| 1871 | Scientific advancement | Ernst Haeckel promotes scientific materialism and evolutionary thought in Germany. Scientific materialism, a philosophy he supports, asserts that reality is based on the material world, excluding spiritual or supernatural phenomena. Haeckel plays a crucial role in popularizing Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in Germany, emphasizing that all living organisms share a common ancestor and evolve through natural selection. He extends these ideas to the evolution of human culture and the mind. Haeckel's advocacy for a scientific, reason-based worldview challenges traditional religious and philosophical perspectives, shaping the intellectual climate of his era.[103] | Germany |

| 1879 | Scientific Advancement | Wilhelm Wundt establishes the first experimental psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig, Germany. This milestone is regarded as the formal foundation of psychology as an academic discipline. Wundt's laboratory focuses on the systematic study of mental processes through experimental methods. Among his notable students are Emil Kraepelin, known for his work in psychiatric classification; James McKeen Cattell, a pioneer in psychometrics; and G. Stanley Hall, who contributed to developmental psychology and founded the American Psychological Association.[104] | Germany |

| 1879 | Philosophical development | German philosopher Gottlob Frege publishes Begriffsschrift, a foundational book and formal system in logic. The title means "concept-writing" and describes a formula language modeled on arithmetic for pure thought. Frege develops this system to rigorously express logical reasoning, introducing quantified variables for the first time. It is a classical, bivalent second-order logic with identity, allowing quantification over objects and relations. Although inspired by Leibniz’s ideal of a universal logical language, Frege acknowledges this is a difficult goal. Begriffsschrift lays the groundwork for analytic philosophy and would influence later thinkers like Bertrand Russell.[105] [106] [107] [108] | Germany |

| 1885 | Organization | The Rationalist Association is founded in the United Kingdom to promote secularism, scientific reasoning, and critical thinking. Originally established as the Rationalist Press Association (RPA), it seeks to make rationalist and scientific literature accessible to the public. The organization would play a key role in advocating for freethought, humanism, and the separation of religion from public affairs. Through its publications, including The New Humanist magazine, the association would influence intellectual and philosophical discourse in Britain. Over time, it would evolve into a broader platform for discussing science, ethics, and rational inquiry in contemporary society.[109] | United Kingdom |

| 1905 | Scientific Advancement | Albert Einstein publishes the theory of special relativity, demonstrating the power of reason and mathematical precision in understanding the universe. The paper explains the relationship between space and time, and how energy and mass are interconnected. It introduces the famous equation E=mc², asserting that energy equals mass times the speed of light squared. This groundbreaking work revolutionizes physics, demonstrating how speed affects space, time, and mass, and how mass can be converted into energy. Einstein's 1905 papers, including one on the particle theory of light, mark his "miracle year" and earns him the 1921 Nobel Prize.[110][111] | Switzerland |

| 1910 | Intellectual movement | Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead publish the first volume of Principia Mathematica, a three-volume work that lays the foundation of mathematical logic. The remaining volumes are released in 1912 and 1913. The book is a key defense of logicism, the idea that mathematics can be reduced to logic, and helps connect mathematics with formal logic. Principia Mathematica significantly influences fields such as philosophy, mathematics, linguistics, economics, and computer science. It would remain a pivotal work in logic, with a second edition released in 1925-1927 and a condensed version published in 1962.[112][113][114] | England |

| 1920s–1930s | Philosophical development | The Vienna Circle (Wiener Kreis) is established in Vienna by a group of philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians who are dedicated to the philosophy of science. Prominent members include Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, and Carl Hempel. The Circle strongly advocates for logical positivism, a philosophy that asserts scientific knowledge is the only valid form of knowledge, rejecting metaphysical reasoning. Central to their approach is the verifiability principle, which posits that the meaning of a proposition is grounded in its empirical verifiability through experience and observation. Additionally, the Vienna Circle promotes the idea of the unity of science, rejecting artificial divisions between the physical, biological, and social sciences. The group disbands in 1938 due to the political upheaval caused by World War II, with many members fleeing to the United States and the United Kingdom.[115][116] | Austria |

| 1921 | Philosophical development | Ludwig Wittgenstein publishes Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus challenging previous understandings of logic and language from a rationalist perspective. Written in concise, numbered statements, it explores the relationship between language and the world. The book opens with "The world is everything that is the case" and concludes with "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Influential on the Logical Positivists, it is completed during Wittgenstein's military leave in 1918. Although his later work, Philosophical Investigations, criticizes many ideas from the Tractatus, it would remain one of his most important philosophical contributions.[117][118][119][120] | Austria |

| 1929 | Literature | The Rationalist Association starts publishing The Rationalist Annual. The publication is designed to promote rationalist ideas, contributing to the intellectual and cultural discourse of the time. It serves as a platform for the dissemination of rationalist thought, addressing various philosophical, scientific, and ethical topics. Through this annual, the Rationalist Association seeks to encourage critical thinking, secularism, and skepticism, advocating for the application of reason and evidence in understanding the world. The publication would play a key role in the broader rationalist movement of the early 20th century.[121][122][123] | United Kingdom |

| 1933 | Philosophical development | The Humanist Manifesto is published as a declaration of humanist principles, emphasizing reason, ethics, and social progress without reliance on religious doctrine. It frames humanism as a progressive, non-theistic philosophy dedicated to improving society. Later versions, including Humanist Manifesto II (1973) and Humanist Manifesto III (2003), refine these ideas, advocating for secularism, scientific inquiry, and human rights. Common themes across all versions include democracy, social justice, and ethical responsibility. These manifestos would serve as foundational texts for modern humanist organizations, shaping contemporary secular and rationalist movements worldwide.[124][125][126][127] | United States |

| 1936 | Literature | British philosopher A.J. Ayer publishes Language, Truth and Logic, a foundational work of logical positivism, a movement originating from the Vienna Circle in the 1920s. Ayer, influenced by Moritz Schlick, presents a clear and rigorous defense of verificationism—the idea that a statement is meaningful only if its truth can be empirically verified. He argues that metaphysical and religious claims are literally meaningless. The book also introduces Ayer’s emotivist theory of ethics, which sees moral statements as expressions of emotion rather than factual claims. Despite controversy, the work would become one of the most influential and widely read philosophical texts of the 20th century.[128] | United Kingdom |

| 1940s | Technological impact | The advancement of computer science is driven by pioneers like Alan Turing, who applies logical reasoning and mathematics to develop foundational theories of computation. During this decade, Turing's contributions to code-breaking and computer design are pivotal to both the British war effort and the emergence of modern computing. He cracks the German Enigma code, invents the Bombe machine to aid cryptanalysis, and develops "Banburismus" to decipher naval Enigma messages. Post-war, he spearheads the design of the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) and contributes to the Manchester Mark 1, an early stored-program computer. His work also lays the groundwork for artificial intelligence, mathematical biology, and the Turing Test, shaping the future of computing.[129][130][131][132][133] | United Kingdom |

| 1945 | Literature | Karl Popper publishes The Open Society and Its Enemies, a critical analysis of totalitarianism. The book argues against the ideas of Plato, Hegel, and Marx, whom Popper sees as laying the foundations for authoritarian regimes. He defends liberal democracy and rationalism, emphasizing the importance of critical thinking, individual freedom, and open discourse. Popper introduces the concept of the "open society," where institutions allow for continuous improvement through reason and debate, in contrast to "closed societies" governed by dogma. His work would become a significant philosophical defense of democracy and a key contribution to political thought in the 20th century.[134] | United Kingdom |

| 1948 | Literature | U.S. mathematician Claude E. Shannon publishes A Mathematical Theory of Communication in the Bell System Technical Journal, laying the foundation for modern information theory. He introduced key concepts such as channel capacity, the noisy channel coding theorem, information entropy, and redundancy. The paper formalizes the term "bit" and presents a model of communication consisting of an information source, transmitter, channel, receiver, and destination. Recognized as one of the most influential scientific works, it would be described as the "Magna Carta of the Information Age."[135] | United States |

| 1950 | Literature | British philosopher Bertrand Russell publishes Unpopular Essays, a collection of writings advocating rationalism, skepticism, and critical thinking. The essays challenge dogma, superstition, and irrational beliefs, reinforcing Russell’s lifelong commitment to intellectual inquiry and empirical reasoning. In the same year, he is awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his extensive contributions to rationalist thought and his ability to make complex philosophical ideas accessible to the public. The Nobel committee recognizes his work in championing humanism, free thought, and social criticism, cementing his influence on both philosophy and public discourse in the 20th century.[136][137][138] | United Kingdom |

| 1952 | Organization | Humanists International, originally known as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU), is established in Amsterdam. This organization serves as a global coalition of humanist, rationalist, secularist, and similar groups, promoting humanist values and ethical philosophies. Its formation marks a significant unification of various humanist traditions, including atheists, freethinkers, and ethical culture societies, which had been developing since the mid-19th century. Over the decades, Humanists International would expand its reach, encompassing numerous member organizations worldwide, all dedicated to advocating for secularism, human rights, and rational inquiry.[139][140][141] | International (based in the Netherlands) |

| 1959 | Philosophical development | Karl Popper publishes The Logic of Scientific Discovery, in which he argues that science is distinguished from non-science by falsifiability: a theory must be testable and capable of being refuted by observation. He criticizes theories like psychoanalysis and Marxism for being non-falsifiable, with Marxism becoming dogmatic over time. Popper rejects inductive reasoning as the basis of science, instead emphasizing problem-solving through testing and falsification. He proposes that scientific theories must be open to refutation, while unscientific theories, despite being insightful, do not meet the criterion of falsifiability, challenging traditional scientific methodologies.[142] | Austria |

| 1950s | Technological impact | Cybernetics and artificial intelligence emerge as key fields, applying rationalist principles to study systems, control, and intelligence. Cybernetics, pioneered by Norbert Wiener, explores feedback loops and communication in machines and living organisms. Meanwhile, AI research, led by figures like Alan Turing and John McCarthy, seeks to develop machines capable of reasoning and learning. These advancements lay the groundwork for modern computing, robotics, and automation, influencing fields from engineering to cognitive science. The decade marks a shift toward viewing intelligence as a process that can be replicated and enhanced through technology.[143] | United States |

| 1962 | Literature | American philosopher William Warren Bartley III publishes The Retreat to Commitment, a work that marks his emergence as a significant voice in 20th-century philosophy. In this book, Bartley introduces the idea of pancritical rationalism (PCR), a radical extension of Karl Popper’s critical rationalism that aims to free rational inquiry from any ultimate, unquestioned commitments. Rather than defending beliefs through justification, PCR holds all positions— including itself—permanently open to criticism. Although Bartley had recently completed his PhD under Popper, the book signals a distinct and ambitious philosophical direction that would later lead to tensions between the two thinkers.[144][145] | United States |

| 1960s | Scientific advancement | The decade sees major advancements in modern logic, reinforcing rationalist ideals in scientific research. Saul Kripke's work on modal logic introduces "Kripke semantics" and the concept of possible worlds, revolutionizing the study of necessity and possibility. Set theory, particularly Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC), continues to be refined. The rise of computers lead to increased applications of logic in artificial intelligence and formal verification techniques. Mathematical logic also influences model theory and proof theory, expanding its role in various scientific and computational fields, shaping modern logic and its applications in technology and philosophy.[146][147][148][149][150] | United States |

| 1970s | Intellectual movement | Noam Chomsky's theory of universal grammar (UG) emphasizes rationalist ideas about the structure of human language. UG posits that all human languages share an underlying structure, with certain universal principles governing language organization. It suggests that language is innate and hardwired into the brain, providing a framework for language acquisition. UG includes language-specific parameters and distinguishes between surface structure and deep structure. While Chomsky's theory is influential, it remains controversial, as some linguists argue that language diversity challenges the idea of a universal grammar. Nonetheless, Chomsky's work highlights the genetic basis for language knowledge.[151][152] | United States |

| 1973 | Philosophical development | The Humanist Manifesto II is published by Paul Kurtz and Edwin H. Wilson as a continuation of the 1933 Humanist Manifesto I, addressing modern global issues. It champions secular humanism, emphasizing reason, ethics, and scientific inquiry as guiding principles for progress. Rejecting supernatural beliefs, it upholds human dignity, individual freedom, social justice, and environmental responsibility. The manifesto critiques authoritarianism, war, and economic inequality while advocating democratic governance and human rights. It envisions a secular society built on human-centered values, cooperation, and rational problem-solving, promoting ethical responsibility and mutual respect as the foundations for a better world.[153][154] | |

| 1974 | Literature | Robert Nozick publishes Anarchy, State, and Utopia, a seminal work in political philosophy that defends libertarianism. Nozick critiques redistributive justice and argues for a minimal state limited to protecting individual rights. He develops the "entitlement theory of justice," asserting that wealth distribution is just if acquired through legitimate means such as voluntary exchange and fair acquisition. The book challenges John Rawls' A Theory of Justice and promotes rationalist principles, emphasizing individual liberty and self-ownership. Anarchy, State, and Utopia would become a foundational text for libertarian thought and would influence debates on the role of government and personal freedom.[155] | United States |

| 1975 | Paul Feyerabend publishes Against Method, a provocative critique of the idea that science must follow a fixed methodology. Arguing for "epistemological anarchism," Feyerabend claims that no single method can account for scientific progress, and that the history of science, particularly Galileo’s defense of heliocentrism, shows rule-breaking often leads to innovation. He challenges the rationalist tradition exemplified by Karl Popper, suggesting that even falsificationism is just one approach among many.[156] Feyerabend proposes “counterinduction”—embracing theories contradicting accepted evidence—as a tool to expose hidden assumptions.[157] The book would remain influential in philosophy of science. [158] | United States | |

| 1975 | Noam Chomsky publishes Reflections on Language, which presents a rationalist perspective on human nature, arguing that certain cognitive capacities—particularly language—are innate rather than learned entirely through experience. Contrasting with the empiricist view of the mind as a "blank slate," Chomsky contends that humans are born with a universal grammar that shapes language acquisition. The book explores the nature of cognitive capacity, the goals of linguistic inquiry, and the complexities of human language. It would become influencial in linguistics and philosophy of mind.[159][160] [161] | United States | |

| 1976 | Organization | American philosopher Paul Kurtz founds the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) to promote scientific inquiry and critical examination of paranormal claims. The organization, later known as the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), is established to counter the uncritical acceptance of paranormal phenomena by the media and society. Founding members include notable figures such as Carl Sagan, Isaac Asimov, and James Randi. CSI's mission is to encourage evidence-based investigation of extraordinary claims and to disseminate factual information to the public.[162] [163] [164] [165][166] | United States |

| 1983 | Conference | The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) organizes the first international conference on skepticism and rationalism, bringing together scientists, philosophers, and skeptics to discuss pseudoscience, paranormal claims, and the promotion of critical thinking. The event aimed to foster global collaboration among skeptics and highlight the importance of scientific inquiry in evaluating extraordinary claims. Key topics included astrology, faith healing, psychic phenomena, and the role of media in spreading misinformation. This conference helped establish skepticism as an international movement and strengthened CSICOP’s influence in promoting rational discourse and scientific skepticism worldwide.[167][168] | United States |

| 1984 | Literature | British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins publishes The Selfish Gene, which introduces the gene-centred view of evolution, portraying it as a rational and mathematical process driven by the interests of genes rather than individuals or groups. Building on the work of George C. Williams and W. D. Hamilton, Dawkins explains how genes can promote altruistic behavior when it benefits genetically related individuals (inclusive fitness). The book also introduces the concept of the meme, a cultural analogue to the gene. Despite its provocative title, much of the book explores the evolutionary basis of cooperation. It would be voted the most influential science book in a 2017 Royal Society poll.[169] [170] [171] | United Kingdom |

| 1990 | Online Community | The online community witnesses the emergence of early rationalist discussions, primarily hosted on Usenet and nascent internet forums. These spaces serve as incubators for intellectual debate, where tech-savvy individuals, academics, and curious thinkers converge to challenge conventional wisdom. The conversations often revolve around science, skepticism, and the critical examination of paranormal claims. This period marks the initial steps towards what would later evolve into organized rationalist communities, setting the foundation for modern skeptical inquiry. Despite technical barriers and limited access, these pioneering discussions play a crucial role in shaping the culture of evidence-based discourse online.[172][173] | Global |

| 1995 | Literature | Carl Sagan publishes The Demon-Haunted World, advocating for scientific thinking and skepticism.[174] The book aims to combat pseudoscience and irrational beliefs by emphasizing the importance of the scientific method and critical inquiry. Sagan explores topics such as UFOs, faith healing, and conspiracy theories, illustrating how scientific literacy can help distinguish fact from fiction. He also warns against the dangers of anti-intellectualism and the decline of public understanding of science. The book would remain a seminal work in popular science, inspiring readers to embrace skepticism and rational thought.[175][176][177] | United States |

| 2000 | Organization | The Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) is founded to study artificial intelligence (AI) safety and rationality. Initially named the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence (SIAI), MIRI aims to ensure that advanced AI systems would be developed safely and aligned with human values. The organization focuses on mathematical foundations of AI alignment, decision theory, and rationality, emphasizing the potential risks of uncontrolled AI development. MIRI would play a key role in the early rationalist movement and would influence discussions on AI ethics, existential risk, and long-term technological progress.[178] [179] [180] [181] | United States |

| 2002 | Literature | Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom publishes Anthropic Bias, which explores how to reason in situations where evidence is influenced by observation selection effects—cases where the evidence exists only because there is an observer to perceive it. Bostrom critiques the Self-Indication Assumption (SIA) and introduces the Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA), later refining it to the Strong SSA (SSSA), which uses "observer-moments" to address paradoxes. He applies these ideas to scenarios like the Sleeping Beauty problem and the Doomsday Argument. The book emphasizes how observation bias affects philosophical and scientific reasoning, especially in cosmology and probability theory.[182] [183] [184] [185] [186] | United Kingdom |

| 2006 | Online Community | Eliezer Yudkowsky and Robin Hanson launch Overcoming Bias, an online community focused on rationality and cognitive biases. The blog explores ways to improve reasoning, avoid common thinking errors, and apply rationalist principles to decision-making. Initially a solo project, it would later become a collaborative platform featuring contributions from other rationalist thinkers. Overcoming Bias lays the foundation for the broader rationalist movement and eventually leads to the creation of LessWrong, a dedicated community for discussions on epistemic rationality, artificial intelligence, and effective altruism. The blog would play a key role in popularizing rationalist ideas and fostering an intellectual community around them.[187] | United States |

| 2006 | Literature | Richard Dawkins publishes The God Delusion, a landmark critique of religion from a scientific and rationalist perspective. Dawkins argues that belief in a supernatural creator or personal god qualifies as a delusion—defined as a persistent false belief held despite strong evidence to the contrary. He contends that morality does not depend on religion and proposes naturalistic explanations for the origins of religious belief and ethical behavior. The book would sell over three million copies worldwide, provoking widespread debate and inspiring a wave of both critical and supportive responses.[188] [189] [190] | United Kingdom |

| 2000s (later half) | Organization | Several communities focused on altruism, rationality, and the future of humanity begin to converge, laying the groundwork for the effective altruism movement. Key groups include GiveWell and its offshoot Open Philanthropy, organizations promoting effective giving and career choices like Giving What We Can and 80,000 Hours, and research institutes such as MIRI and the Future of Humanity Institute. In 2011, Giving What We Can and 80,000 Hours would unite under the Centre for Effective Altruism. The movement would draw additional support from followers of philosopher Peter Singer, who would publicly endorse the term "effective altruism" in a 2013 TED talk.[191] [192] [193] [194] [195] [196] | United States, United Kingdom |

| 2009 | Online Community | LessWrong is launched as an online community and blog, created to explore and promote rationalist philosophy. Founded by Eliezer Yudkowsky and others from the rationalist community, the site focuses on improving thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving using principles from cognitive science, logic, and Bayesian reasoning. The blog features articles on topics like cognitive biases, artificial intelligence, ethics, and epistemology. LessWrong would become a central hub for the growing rationalist movement, encouraging thoughtful discussions, critical thinking, and the application of rationality to everyday life. Its community would grow to influence fields like effective altruism, AI alignment, and futurism.[197][198] | United States |

| 2010 | Literature | American philosopher Sam Harris publishes The Moral Landscape, in which he argues that science can and should be used to determine moral values. Harris challenges the idea that morality is either subjective or divinely ordained, proposing instead that moral truths are grounded in the well-being of conscious creatures. He claims that moral questions have objective answers that can be discovered through empirical methods. Rejecting the philosophical separation of facts and values, Harris argues that science can identify actions and systems that promote human flourishing. The book builds on his neuroscience background and his doctoral thesis of the same title.[199] [200] | United States |

| 2010s | Social movement | Effective Altruism and LessWrong communities emerge, promoting rationalist approaches to ethics and decision-making. EA, influenced by thinkers like Peter Singer and William MacAskill, focuses on using evidence and reason to maximize positive impact in charitable giving and global issues. LessWrong, founded by Eliezer Yudkowsky, becomes a hub for rationalist thought, emphasizing cognitive biases, Bayesian reasoning, and AI safety. The two communities share a commitment to applying logic and empirical analysis to improve decision-making, influencing fields such as philanthropy, policy, and artificial intelligence. Their ideas continue to shape discussions on ethics and rationality today.[201][202] | Global |

| 2011 | Literature | Daniel Kahneman publishes Thinking, Fast and Slow, a landmark book on cognitive biases and decision-making. Kahneman introduces the concepts of System 1 (fast, intuitive thinking) and System 2 (slow, deliberate reasoning), explaining how biases affect judgment. The book significantly influences rationalist discourse, reinforcing the importance of Bayesian reasoning and cognitive debiasing. It becomes widely referenced in effective altruism, artificial intelligence safety, and behavioral economics, shaping discussions on human rationality and decision-making.[203][204][205][206] | United States |

| 2011 | Literature | British physicist David Deutsch publishes The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations that Transform the World, which expands on Karl Popper’s philosophy of knowledge, emphasizing the role of "good explanations"—those that are testable and resistant to revision—in driving human progress. Deutsch argues that the Enlightenment initiated an endless potential for knowledge creation, made possible by creativity, critical thinking, and open inquiry. He explores scientific concepts such as quantum theory and the multiverse to support his vision of an optimistic future shaped by reason. He critiques deterministic accounts of history, instead highlighting the problem-solving power of knowledge. The book would be lauded for its scope, though some would criticize its speculative aspects.[207] | United Kingdom |

| 2012 | Organization | The Center for Applied Rationality (CFAR) is established to provide training in rational thinking, decision-making, and cognitive optimization. Founded by members of the effective altruism and rationalist communities, CFAR develops workshops and curricula based on cognitive science, behavioral economics, and Bayesian reasoning. Its programs aim to help individuals improve their reasoning skills, avoid cognitive biases, and make better decisions in personal and professional contexts. CFAR would be influential within the rationalist movement, collaborating with organizations like the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) and attracting participants interested in effective altruism, AI safety, and applied rationality.[208][209] | United States |

| 2020 | Scientific and ethical development | Rationalist principles, such as logic, reason, and evidence, become crucial in AI ethics, helping to identify and mitigate bias, ensure fairness, promote transparency, and establish accountability in AI systems. These principles guide the responsible development of AI. Additionally, AI plays a significant role in global priorities research by analyzing complex issues like climate change and poverty, developing innovative solutions, and aiding decision-making. By applying AI to these challenges, we can enhance our understanding and create better strategies. Overall, the integration of rationalist principles and AI in addressing global issues ensures responsible, beneficial development.[210][211][212][213] | Global |

| 2021 | Philosophical development | Eliezer Yudkowsky publishes Rationality: From AI to Zombies, which attempts to offer a comprehensive exploration of rationalist thinking. The book delves into decision-making, cognitive biases, and artificial intelligence, drawing from Yudkowsky’s writings on LessWrong and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI). It presents a systematic approach to rationality, emphasizing Bayesian reasoning, epistemic humility, and effective decision-making strategies. The work is influential in both AI alignment and the broader rationalist community, shaping discussions on intelligence, ethics, and human cognition.[214][215][216][217] | United States |

| 2022 | Philosophical development | In present-day discussions on forums like LessWrong, there is increasing reflection on the historical entanglements of prominent rationalist figures with political ideologies. These discussions often center around the potential pitfalls of ideological bias, as well as the dangers of overconfidence in predictive reasoning. A key concern is how historical figures, such as J.B.S. Haldane, were influenced by their political affiliations, which might have clouded their objectivity. Modern examples of such biases can be seen in debates about the COVID-19 response, the lab-leak theory, biosafety research, and critiques of institutions like the FDA. These conversations aim to explore how these issues may mirror past mistakes and emphasize the importance of epistemic humility in today's complex, politically charged environment.[218] |

Numerical and visual data

Google Trends

This Google Trends data below shows worldwide search interest in "Rationalism" from 2004 to February 2025, when the screenshot was taken. There's a clear downward trend over this period, indicating declining public curiosity about rationalism. This could be due to various factors, such as shifting philosophical interests or the term becoming less relevant to everyday discourse.[219]

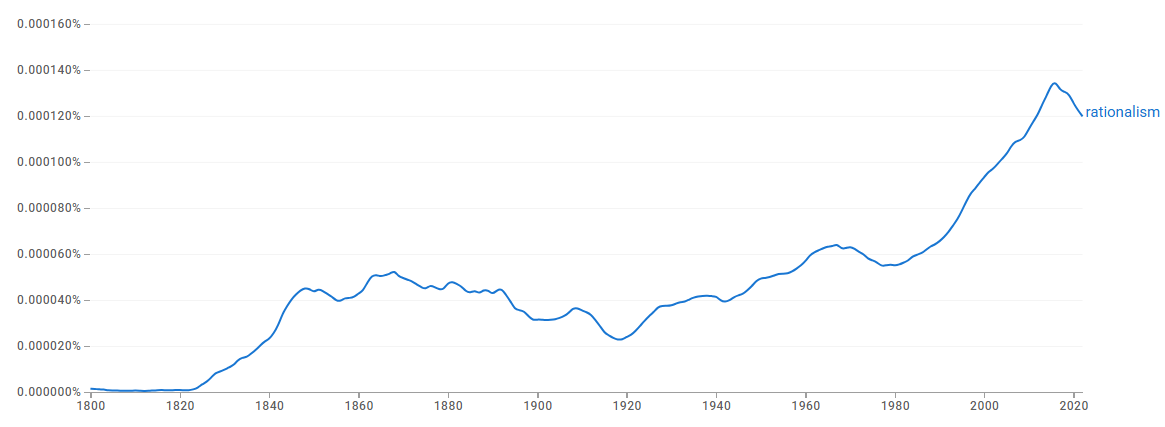

Google Books Ngram Viewer

The graph from Google Books Ngram Viewer below displays the frequency of the term "rationalism" in books from 1800 to 2019. Usage rises gradually in the early 19th century, peaking around 1860, likely due to Enlightenment influences. After fluctuating for decades, it declines in the early 20th century, possibly due to the rise of empiricism and pragmatism. A moderate recovery starts after 1940, followed by a sharp increase after 2000, peaking around 2015–2019. The recent decline suggests a shift in intellectual focus. Overall, the graph reflects the evolving relevance of rationalism in philosophical and cultural discourse over time.[220]

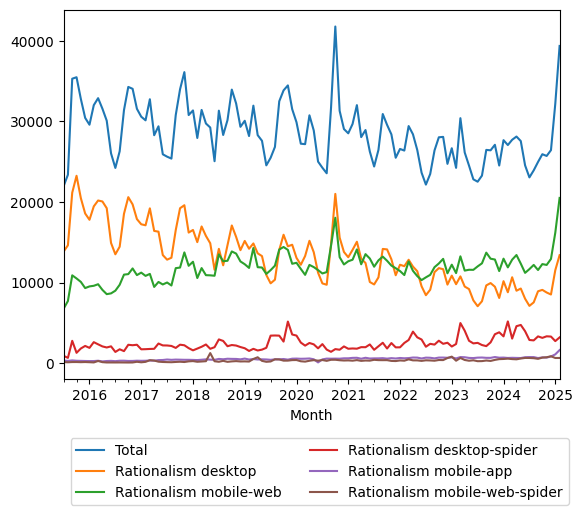

Wikipedia Views

The graph below represents Wikipedia page views for the article Rationalism across different platforms from July 2015 to February 2025. The total views (blue) exhibit a general decline with periodic spikes. The sharp peaks, particularly in 2021 and late 2024, could indicate increased interest due to external events or academic cycles. Overall, mobile access remains significant, suggesting evolving user behavior over time.[221]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "Rationalism - By Movement / School - The Basics of Philosophy". www.philosophybasics.com. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Vienna Circle and Verificationism". Fiveable Library. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Sterling, L.C. "The Limits of My Language Mean the Limits of My World". Medium. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Aristotle's Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Euclid". Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Archimedes". Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Contemporary lessons from the fall of Rome". OUPblog. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Buddhist Logic and Epistemology" (PDF). University of Delhi. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Lam, Chi-Ming. "Confucian Rationalism". Educational Philosophy and Theory. doi:10.1080/00131857.2014.965653. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Scientific Revolution". Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Rationalism: Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz". Logos. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Sources of Knowledge: Rationalism, Empiricism, and the Kantian Synthesis". Rebus Community. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Sterling, L.C. "The Limits of My Language Mean the Limits of My World". Medium. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ "Universal Grammar". Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ↑ Ms. Bijuli Rajiyung (2024). "From Mythos to Logos: Pre-Socratic Philosophers and the Birth of Rational Inquiry" (PDF). International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR). Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ↑ "Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle". Fiveable Library. Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ↑ "Aristotle's Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ↑ "Ancient Greek Political Thought". Fiveable Library. Retrieved February 11, 2025.

- ↑ "Philo of Alexandria". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Philo of Alexandria Sought to Combine Greek Thought with Sacred Scripture". Mosaic Magazine. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Philo of Alexandria". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Philo of Alexandria". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Faith and Reason in the Thought of St. Augustine". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Why Does St. Augustine Appear to See No Conflict Between Faith and Reason?". Study.com. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Faith and Reason: Part 2 – Augustine (Summer 2018 Series)". Emerging Scholars Blog. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Augustine's Confessions and the Harmony of Faith and Reason". Catholic.com. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ "Faith and Reason". Reasons to Believe. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ↑ The Islamic Golden Age: A Story of the Triumph of the Islamic Civilization. 2016. pp. 25–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24774-8_2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (help) - ↑ "Ibn Sina (Abu 'Ali al-Husayn) (980–1037)". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Avicenna". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Faith and Reason". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Ibn Sina". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "The Rise of Scholasticism and Medieval Philosophy". Fiveable. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ↑ "Augustine and Scholasticism". Pressbooks. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ↑ "Modern Western Philosophy" (PDF). Nowgong College. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ↑ "Galileo Galilei". New Mexico Space Museum. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Cosmology". NASA StarChild. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "History of the American Physical Society". American Physical Society. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "What Did Galileo Discover?". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Descartes Publishes His Scientific Method". Wired. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Key Questions and Answers". SparkNotes. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Leviathan". Goodreads. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Leviathan Then and Now". Hoover Institution. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes: Summary, Quotes & Analysis". Study.com. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "References Papers: Malebranche". scirp.org. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "Malebranche on the Emotions (SEP)". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "Nicolas Malebranche: The Search After Truth (excerpts)". historymuse.net. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "The Search After Truth". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "Malebranche, The Search After Truth (PDF)" (PDF). people.tamu.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "Spinoza on Free Will and Determinism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Baruch Spinoza". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Baruch Spinoza: Life, Ethics & Philosophy". Study.com. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ↑ "Preestablished Harmony". Britannica. Retrieved 20 February 2025.