Timeline of food and nutrition in China

This is a timeline of food and nutrition in China, describing agricultural and industrial food production, organizations, government policies and infrastructure related to food, as well as the level of nutrition of the population.

Contents

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- How did political regimes affect the production of food and the nutrition of the Chinese?

- What are some revealing figures on food production and how did they evolve?

- What changes can be seen in the nutrition of the population, including nutrient intake and changes of diet?

- How did the historical scenario evolve from repeated famines to overnutrition in the last decades?

Numerical and visual data

| Year | China | Indonesia | Malaysia | Philippines | Thailand | Vietman | United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | ||||||||||

| 1981 | ||||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||||

| 2001 |

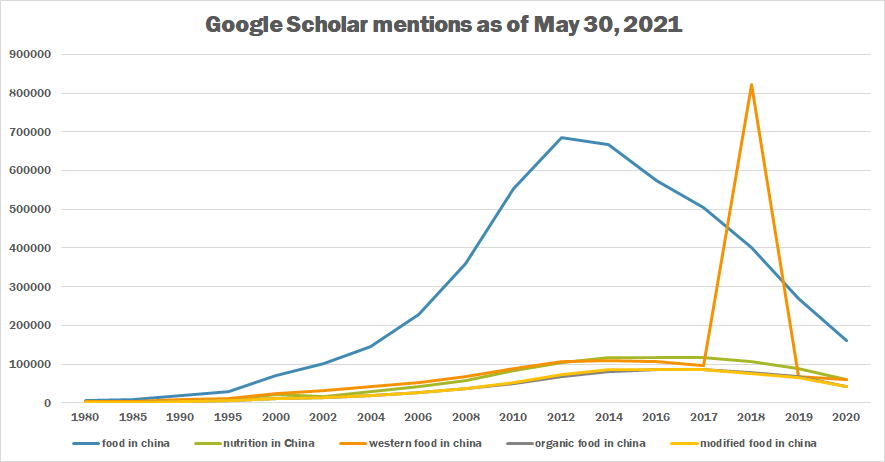

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 30, 2021.

| Year | food in china | nutrition in China | western food in china | organic food in china | modified food in china |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 7,130 | 1,800 | 3,860 | 1,150 | 1,350 |

| 1985 | 8,210 | 2,170 | 4,120 | 1,610 | 1,860 |

| 1990 | 19,200 | 7,460 | 8,460 | 3,450 | 4,110 |

| 1995 | 30,400 | 8,040 | 12,000 | 5,870 | 6,290 |

| 2000 | 71,700 | 20,800 | 24,400 | 10,800 | 12,100 |

| 2002 | 101,000 | 17,600 | 32,200 | 13,100 | 14,500 |

| 2004 | 146,000 | 29,000 | 42,300 | 18,700 | 20,300 |

| 2006 | 229,000 | 42,100 | 53,000 | 27,100 | 28,000 |

| 2008 | 361,000 | 58,500 | 68,300 | 38,000 | 37,900 |

| 2010 | 554,000 | 84,300 | 88,500 | 50,000 | 52,300 |

| 2012 | 684,000 | 104,000 | 107,000 | 69,400 | 74,500 |

| 2014 | 668,000 | 116,000 | 110,000 | 81,000 | 86,700 |

| 2016 | 573,000 | 118,000 | 106,000 | 87,300 | 86,100 |

| 2017 | 505,000 | 117,000 | 95,500 | 86,200 | 86,200 |

| 2018 | 402,000 | 108,000 | 82,1000 | 78,800 | 75,900 |

| 2019 | 269,000 | 88,500 | 68,900 | 67,300 | 66,700 |

| 2020 | 162,000 | 61,200 | 60,400 | 42,900 | 43,600 |

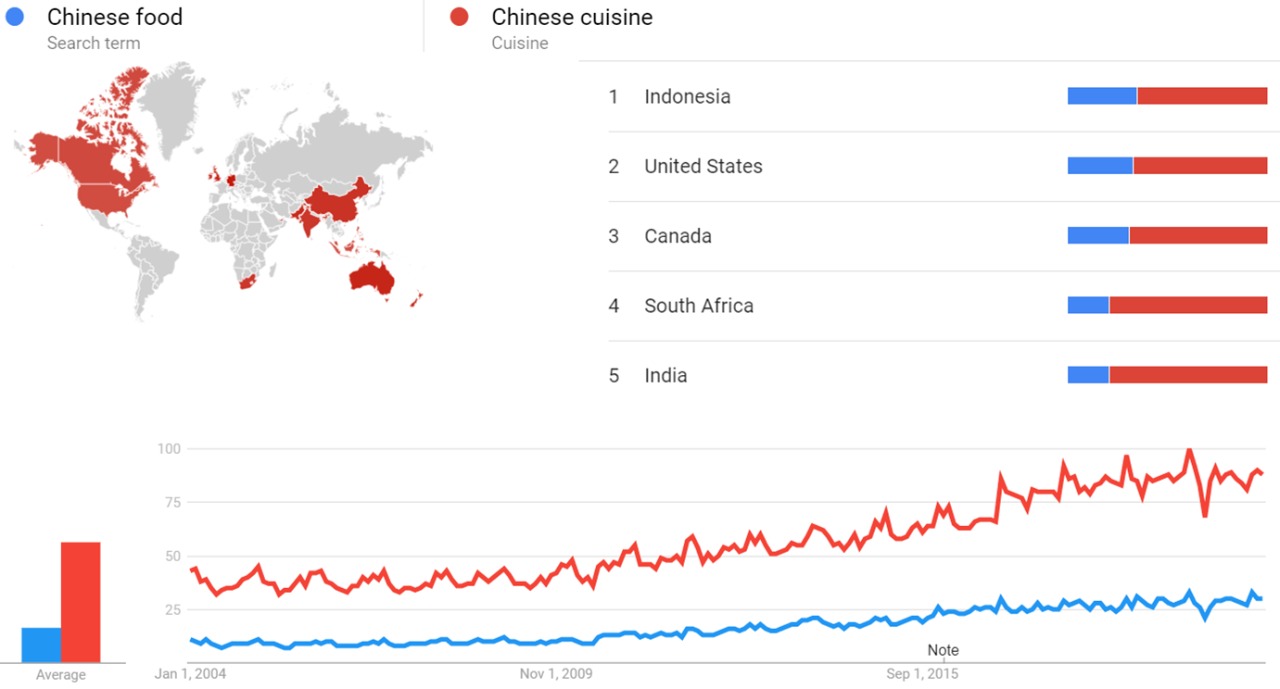

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Chinese food (Search term) and Chinese cuisine (cuisine), from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[1]

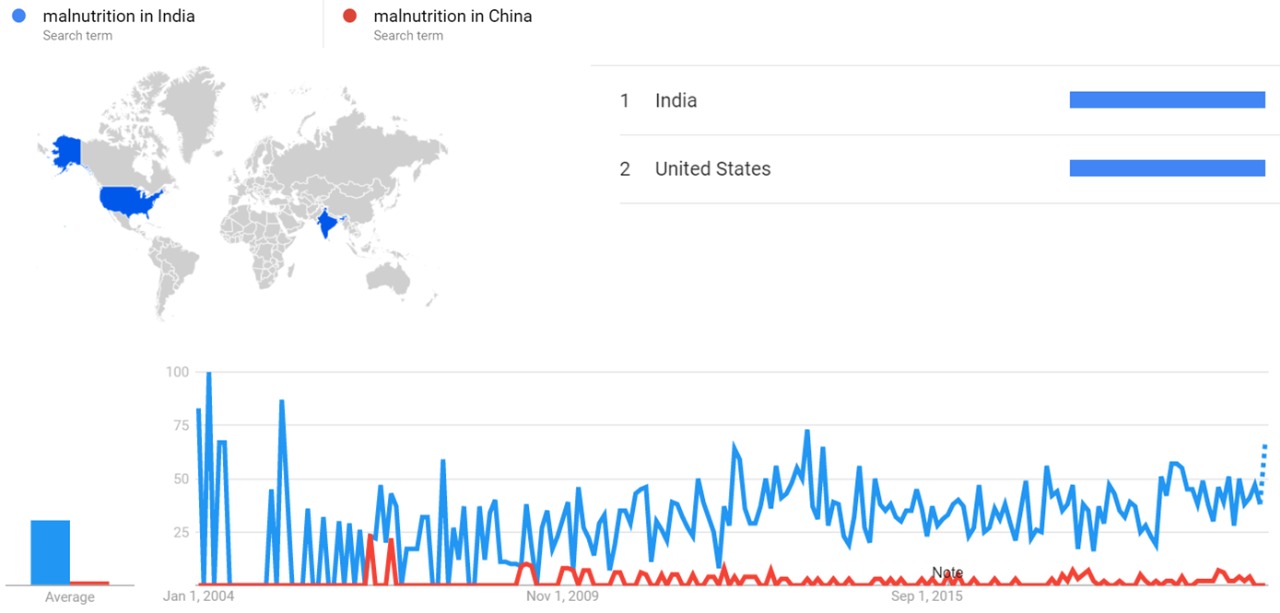

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Malnutrition in India (Search term) and Malnutrition in China (Search term), from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[2]

Other

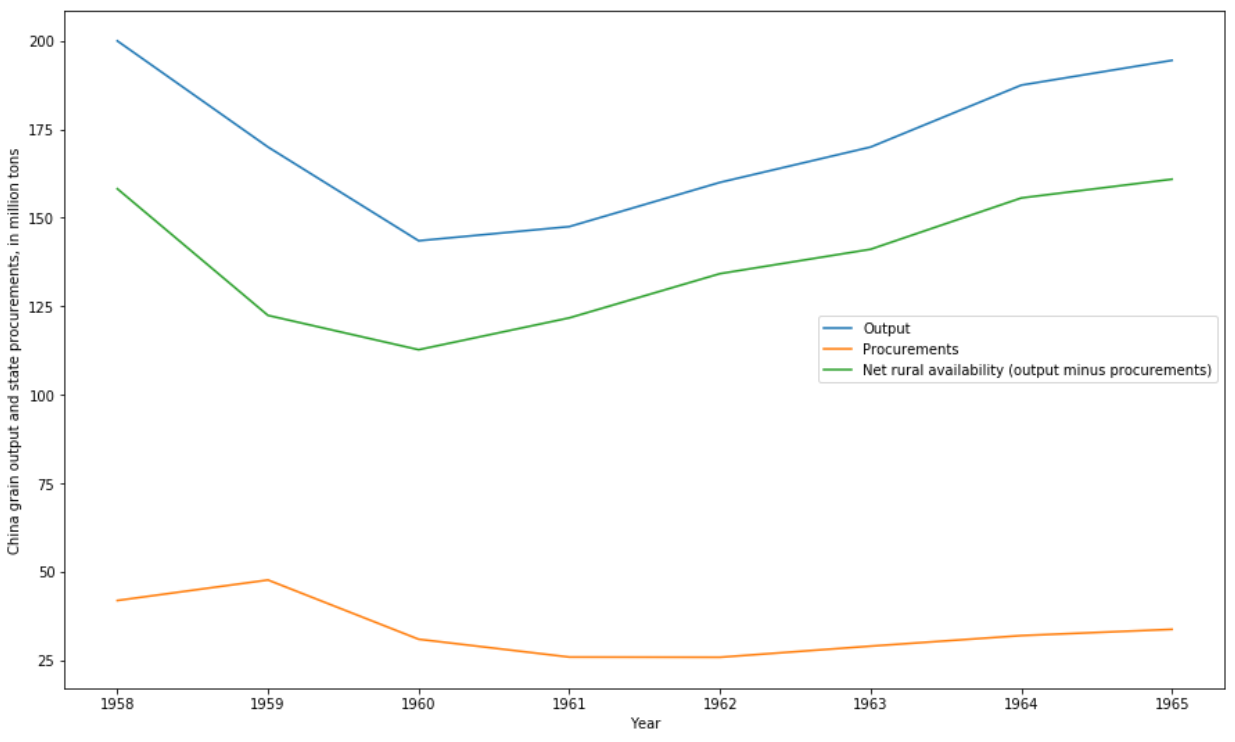

The image below shows the grain output in China during the years of the Great Leap Forward.[3] The Great Chinese Famine occured between 1959 and 1961.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| 221 BC–1912 AD | Imperial China | Imperial China can be considered as a stable civilization, leading the world in art and technology, which includes advances in agriculture and food production, as well as a notable literature on nutrition. However, major food crisis as famines are recorded during this long period. |

| 1912–1949 | Republic of China period | After over two thousand years of imperial rule, a republic is established to replace the monarchy. The Republican era is a period of turmoil. From 1913 to 1927, China disintegrates into regional warlords, who fight for authority, causing misery and disrupting growth. As a result, a number of famines break out.[4] |

| 1949–1977 | Period of central planning | First years of the People's Republic of China. The Communist Party of China applies the economic and social campaign called Great Leap Forward, launched to transform the country from an agrarian economy into a communist society through the formation of People's communes. A direct result of this campaign is the Great Chinese Famine, the worst famine in recorded history. A remarkable rebound and improvement is experienced since the Cultural Revolution[5], launched by Mao Zedong from 1966 until 1976 with the purpose to recover from the failures of the Great Leap Forward. In terms of calorie intake, food consumption in Chinese increases steadily since the early 1970s.[6] |

| 1978–1984 | Socialist market economy | Deng Xiaoping institutes significant economic reforms and China transitions to a socialist market economy. Agriculture is decollectivized. Since the 1980s, the nutrition transition in China rapidly occurs as the political and economic climates evolve. The buying power per children increases significantly as the result of the one-child policy, whereby the only child is constantly lavished with care by his or her parents and grandparents.[7] Vegetable consumption declines substantially during the 1980s.[8] Since 1980s, China gradually opens its agricultural market.[9] |

| 1990s | Self-sufficiency | Over the course of the decade, there is a remarkable fall in the national prevalence of child undernutrition in the country.[10] In 1995 China reaches its target of 95 per cent food self-sufficiency. Obesity increases tremendously during this decade.[11] |

| 21st century | Recent years | The food market further liberalizes, with only limited government regulations. In the 2010s, China becomes the largest global importer of food and beverages. |

Full timeline

| Year | Category | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7500 BC | Food | Production | According to Jared Diamond, the earliest attested domestication of rice takes place in China around this time.[9] |

| 1766 BC–1154 BC | Nutrition | Scientific development | Early Shang Dynasty. People cook herbs to treat diseases. Minister Yi Yin invents cooking wares and soup and broth making techniques.[12] |

| 1122 BC–721 BC | Nutrition | Scientific development | West Zhou Dynasty. In the imperial palace “Food Doctors” select and prepare meals for Kings, using vegetables, fruits, grains, poultry, meats, herbs, and other ingredients. The thought is to make food that is both delicious and health preserving. At this time, “Food doctors” have higher status than “disease doctors” (Internists) and “Carbuncle Doctors” (Surgeons). Theses “Food doctors” are considered the first professional nutritionists.[12] |

| c.1000 BC | Food | Production | The Chinese first cultivate the wild soybean.[13] |

| 722 BC–481 BC | Food | Infrastructure | Spring and Autumn Period. Two revolutionary improvements in farming technology take place. One is the use of cast iron tools and beasts of burden to pull plows, and the other is the large-scale harnessing of rivers and development of water conservation projects.[9] |

| 630 BC–593 BC | Food | Infrastructure | Chinese hydraulic engineer Sunshu Ao lives. His work is focused upon improving irrigation systems.[9] |

| 5th century BC | Food | Infrastructure | Chinese hydraulic engineer Ximen Bao lives. He is credited as the first engineer in China to create a large canal irrigation system.[9][14] |

| 403 BC-221 BC | Nutrition | Scientific development | Warring States period. Doctors pay much attention to nutrition and food therapy. Chinese physician Bian Que says, "As a Doctor, one should investigate the origin of, and pathological changes created by diseases and then treat the patient with food. If food does not cure the disorders, then medicine is given." This advice would influenced succeeding generations of Physicians.[12] |

| 221 BC-220 AD | Nutrition | Literature | Chinese book on agriculture and medicinal plants Shennong Ben Cao Jing is written. It is recognized as the first Chinese materia medica. The text includes references to many grains, fruits, herbs, fishes, poultry and other meats as well as minerals. Dates, sesame seeds, grapes, walnuts, lotus seeds (Lian Zi), Chinese yams, beans, scallions, honeys, and salt are examples of substances recognized as having medicinal qualities.[12] |

| 1st century BC | Food | Infrastructure | The Chinese invent the hydraulic-powered trip hammer for agricultural purposes.[9] |

| 150AD–2019AD | Nutrition | Literature | Preeminent Chinese medical sage Zhang Zhongjing recounts his experiences in using rice and other foods with medicinal herbs in his book A Treatise on Febrile and Miscellaneous Diseases. His “angelica, ginger and lamb broth” is still popular in the 21st century.[12] |

| 25Ad–220AD | Food | Production | Soy milk and tofu are alrerady prepared around this time, as revealed by a stone slab with a mural featuring a kitchen scene which illustrations.[13] |

| 618 AD–907 AD | Food | Infrastructure | Tang Dynasty. China becomes a unified feudal agricultural society. Improvements in farming machinery during this era include the Mouldboard plough and watermill.[9] |

| 670AD-907AD | Nutrition | Literature | Tang Dynasty. Chinese physician Sun Simiao lists over 154 foods in his book Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Talents of Gold. He says, “Food can expel pathogens and protect the internal organs, make people happy, and benefits the Qi and blood. A good Doctor explores the origins of a disease and and its pathogenesis, then prescribes foods to treat the patient. Medicine should be used only if food therapy fails. His student Meng Xian writes the book, Nourishing Recipes in which he increases the number of foods to 241. Meng Xian's student Zhang Ding revises this book and names it Dietetic Materia Medica, the first Chinese book on dietetic therapies and actions of foods, cooking techniques, along with dietary principles discussed.[12] |

| 960 AD–1278 AD | Nutrition | Literature | Song Dynasty. The government orders medical officials Wang Huan Yin et al to compile Peaceful Holy Benevolent Prescriptions, which lists dietetic therapies for 28 diseases. Around the same time, Chen Zhi’s book, Care of Aged Parents, lists 162 dietetic recipes for older people.[12] |

| 1206 AD–1341 AD | Nutrition | Scientific development | Yuan Dynasty. Dietetic therapy reaches a peak in this period.[12] |

| 1330 | Nutrition | Literature | Chinese court dietitian Hu Sihui writes Yin-shan zheng-yao (Essentials of eating and drinking), which would become a classic in Chinese medicine and Chinese cuisine.[15][16] The book describes 94 courses of food including such factors as types of foods which balance each other and the order in which foods are served, 35 kinds of soup, and 29 recipes for longevity. It also discusses the toxicity of foods and dietary hygiene. This is considered the first complete, systematic book on Chinese nutrition and dietetic therapy.[12] |

| 1333–1337 | Nutrition | Crisis | The Chinese famine of 1333–1337 breaks out resulting from a series of climatic disasters in the country.[17] An estimated 6 million people perish by the famine.[18] |

| 1368 AD–1644 AD | Nutrition | Literature | Ming dynasty. An even deeper understanding of nutrition and dietetic therapy develops. Many nutrition and diet therapy books such as Li Shizhen's Compendium of The Materia Medica, Lu He’s A Dietary Material Medica, Bao Sagan’s The Collection of Vegetables and Wang Shixiong's A Collection of Recipes in Leisure Residence, are published. All of theses texts discuss the properties, actions and indications of foods, and dietary structure, from different angles.[12] |

| 1578 AD–1593 AD | Nutrition | Literature | Chinese Physician and naturalist Li Shizhen writes Compendium of The Materia Medica, a monumental work listing many dietary therapy recipes which placed most foods in the pharmacopoeia.[12] |

| 1876–1879 | Nutrition | Crisis | Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–79.[19][20][21] |

| 1905 | Food | Education | The China Agricultural University is founded.[22][23][24] |

| 1907–1911 | Nutrition | Crisis | Great Qing Famine. With an estimated death toll of around 25 million people, it is the second-worst famine in recorded history[25][26][27][28] |

| 1914–1915 | Food | Production | The average number of horses, mules and asses in China and dependencies is about 9,700,000, and the number of cattle 22,000,000, which likely includes water buffalo.[29] |

| 1920–1921 | Nutrition | Crisis | 1920–1921 North China famine. A drought in five Chinese provinces lasting twelve months provoques a famine, killing around 500,000 people.[30][31][32] |

| 1921 | Background | The Communist Party of China is formed.[33] | |

| 1928–1930 | Nutrition | Crisis | A famine in Northern China breaks out, first affecting coastal Shandong Province, and then shifting northwest to inland Henan, Shaanxi and Gansu. Warfare and drought disaster across the region are considered the cause of the famine. Death toll ranges from 3 to 10 million people.[34][35][36] |

| 1936–1937 | Nutrition | Crisis | The Sichuan famine breaks out as the product of severe drought in the region. Agravated by civil war, the death toll is estimated at around five million.[37][38][39] |

| 1939 | Nutrition | Policy | The Committee on Nutrition of the Chinese Medical Association sets the recommended calorie requirement for an adult Chinese in a temperate climate and living not by manual labor but in an ordinary way, at 2400 per day. This is the same amount considered adequate for Europeans.[40] |

| 1941 | Nutrition | Crisis | Another 2.5 million die in Sichuan during a famine.[41] |

| 1942–1943 | Nutrition | Crisis | A famine in Henan Province between the summer of 1942 and the spring of 1943 leads to the death of between 1 and 3 million people. The crisis is caused by strong drought, the ongoing destruction of fields by swarms of locusts, the demand for supplies for the troops engaged against the Japanese, and also by the unreasonable demands of the government who practically takes all goods of the local farmers.[42][43][44] |

| 1949 | Food | Policy | The People's Republic of China is founded. Shortly after, a nationwide agrarian reform to abolish the feudal system of landownership is implemented over a three-year period. After the land redistribution, peasants would find great incentives to accelerate agricultural production. Both the total production and per caput consumption of major food items would increase steadily until 1957.[45] In 1949, total mortality rates, infant mortality rates, and maternal mortality rates are 30 per 1,000; 200 per 1,000; and 1,500 per 100,000, respectively. Life expectancy is only 35 years. Hundreds of thousands of people starve and die of hunger.[5] |

| 1952 | Food | Consumption | National per capita cereal consumption is reported at 541.2 grams per day (70.0% coarse grains).[5] |

| 1952 | Food | Infrastructure | 88.2% of the Chinese population farm. Without advanced technology and fertilizers, farming requires tremendous amounts of time and labor. The major transportation mode is walking. There is no electricity, and there are no televisions, no private cars, few public buses, and few bicycles.[5] |

| 1953 | Food | Policy | To solve the problem of supplying grain, especially to poor people, a state monopoly for purchasing and marketing grain is implemented nationally by the end of the year, replacing free trade of grain and oil. The peasants' surplus grain is purchased by the government at a fixed price and then sold to urban residents and grain-deficient rural households at a low price.[45] |

| 1955 | The State Council formulates special policies on grain processing and institutes a rationing system. According to a quota determined by age, occupation and intensity of labour by the urban individual, coupons for grain are provided each month to all urban households.[45] | ||

| 1955 | Food | Consumption | Per capita urban pork consumption is reported at 9.7 kilograms per year.[46] |

| 1958 | Food | Policy | The People's Commune system starts being practiced in rural China. Under this system, peasants within a township are organized into a commune consisting of production brigades which were divided into teams. Land, livestock and other production materials are owned collectively, and production team members usually work together or in groups assigned by a leader. Peasants accumulate work points and are paid in food and perhaps small amounts of cash. This system seriously dampens their enthusiasm and the rural economy declines.[45] |

| 1958–1961 | Food | Consumption | Per capita urban pork consumption falls to only 1.7 kilos during the Great Leap Forward period.[46] |

| 1959–1961 | Nutrition | Crisis | The Great Chinese Famine breaks out as a direct consequence of the Great Leap Forward campaign. It is the largest famine in recorded human history, with a consensus at around 30 million deaths, though estimates range from 10 million to as high as 47 million.[47][48][49][50] |

| 1961 | Food | Production | The grain output was only 143,5 million tons, a figure similar to that of 1951.[45] |

| 1962 | Food | Consumption | Cereal consumption drops to its lowest level.[5] |

| 1971 | Food | Consumption | As of date, Chinese food consumption is lower than most of its Asian neighbours.[6] |

| 1978 | Policy | The Chinese government institutes the One-child policy, as part of a birth planning program designed to control the size of the population. The only child is therefore constantly lavished with care by his or her parents and grandparents. This would result in an increased buying power enjoyed by children.[7] | |

| 1978 | Food | Consumption | Consumption of fishery products by households starts increasing steadily because of the growing domestic supply.[46] |

| 1978 | Food | Policy | The People's Commune system is replaced by a rural household production responsibility system. This system allows each rural household to use a piece of land and provide grain to the local government at the state-ordered rate according to the household's contract. The household can dispose of remaining produce as it wishes. This new system is considered to place agricultural development on a more positive track.[45] |

| 1978–1989 | Food | Production | Per capita agricultural production rises from about 316kg to 367 in the period.[51] |

| 1979 | Food | Policy | The Chinese Government starts implementing major land, social, and economic reforms. The country’s economy and agricultural productivity would change greatly after this time.[5] |

| 1979 | Food | Production | Forestry, animal husbandry, fishery and associated production account for 32.2 percent of the total value of agricultural output.[45] |

| 1979–1983 | Food | International trade | The average annual amount of grain imported is 14 million tons.[51] |

| 1980–1996 | Food | Consumption | Poultry per capita at-home consumption triples from 0.76 to 2.44 kilos in the period, while its share in total meat consumption doubles, from 7.2 percent to 14.2 percent. Egg output grows from 2.6 million tons to 19.5 million, while per capita at-home consumption increases from 2.04 kilos to 5.03 kilos. Beef's share of total meat consumption rises from 2.5 percent to 5 percent.[46] |

| 1980–1996 | Food | Production | Aquatic product output rises from 4.5 million tons to 32.9 million, accounting for the most rapid growth among all animal protein products, and making China the world's largest producer. Beef production rises sixfold in the same period, however, beef still accounts for only a small share of the national total meat consumption.[46] |

| 1980 | Nutrition | Statistics | Malnutrition is reported at a 30% of the population.[52] |

| 1981 | Food | Policy | The State Council announces that "prioritizing grain production and actively promoting a diversified agro-economy" would be the principle for adjusting the structure of agriculture. An emphasis is put on the importance of coordinated development of forestry, animal husbandry and aquatic production in association with agriculture. Land that has been inappropriately developed for crops is returned to other uses.[45] |

| 1981–1990 | Food | Land use | The area planted in crops decreases from almost 115 million hectares to about 113.5 million hectares in the period, a 1.3 percent rate of decrease.[45] |

| 1982 | Nutrition | Overnutrition | Overweight problems among the population start emerging.[5] |

| 1982 | Food | Consumption | Cereal consumption reaches a peak in the year.[5] |

| 1982 | Food | Infrastructure | China has about 500 milk processing plants with a daily capacity of 4,000 tons and an annual output of 997,000 tons.[46] |

| 1982–1992 | Food | Consumption | During the period, there is a reduction in the intake of all major food groups except for meat, fish, milk and milk products, eggs and oils and fats. As a consequence, there is an increase in the share of protein and fat in total energy intake from 10.8% to 11.8% for protein and from 18.4% to 22.0% for fat.[53] The national average intake of energy slightly decreases from 2485 to 2328 kcal/caput/day, probably due to the more sedentary lifestyle of the population.[53] |

| 1982–2017 | Food | Production | Total grain output increases 74% from 354 million tons to 618 million tons in this period, surpassing the growth of its population by about 34%.[54] |

| 1984 | Food | Policy | About 99 percent of farm production teams adopt the Family Production Responsibility System. The government begins further economic reforms, aimed primarily at liberalizing agricultural pricing and marketing.[9] |

| 1984 | Food | Production | Grain production increases from 282 million tons to 407 million in the period.[46] |

| 1984 | Food | Production | Forestry, animal husbandry, fishery and associated production increase remarkably in relative importance, accounting for 41,9 percent of the total value of agricultural output compared with 32.2 percent in 1979.[45] |

| 1985 | Food | Production | Floods, droughts and other natural disasters in major agricultural provinces lead to a sharp decline in food supply.[6] However, China has a grain surplus for the first time since 1961.[51] |

| 1985 | Food | Policy | The Chinese Government ends the unified food purchase and supply scheme, which indicates the growing role of the market in the regulation of food supply in the country.[6] |

| 1985–1988 | Food | Production | The Chinese population grows by 3.3 per cent in the period, although the output of rice, wheat and corn declines by 4 per cent, 0.6 per cent and 0.6 per cent, respectively.[6] |

| 1985–1991 | Food | Consumption | Per capita urban pork consumption increases from 16.8 kilograms to 20.6. Per capita rural pork consumption rises from 10.3 kilograms to 11.3.[46] |

| 1985–1996 | Food | Consumption | Per capita total meat consumption (pork, beef, mutton, poultry, and fish products) increases 15 percent for urban households and 33 percent for rural households.[46] |

| 1986–1996 | Food | Production | National total animal protein output reportedly triples, from 38.1 to 118.3 million tons.[46] |

| 1987 | Food | Policy | The Chinese government implements a strategy for agricultural development known as "promoting agriculture by sciences and technology". A large number of scientists are sent to the countryside to offer technical assistance in the use of advanced methods for production of grain, cotton, edible oil, livestock and fish. The state increases the utilization of chemical fertilizer, agricultural machinery and irrigation, trains agricultural technicians and popularizes advanced techniques. It is estimated that 30 to 40 percent of the total increase in agricultural production is attributable to science and technology.[45] |

| 1987 | Food | International trade | Total grain net imports amount to 13 million tons in the year. Although this figure would subsequently decline, China would remain a net importer of cereals even after a strong recovery of grain production between 1989 and 1991.[51] |

| 1988 | Food | Policy | A national project to promote the production of non-staple food and secure the market supply (known informally as the "Food-Basket Project") is proposed by the Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China and approved by the State Council. The project is implemented nationwide and remarkable improvements in production, marketing and consumption of non-staple foods would be made.[45] |

| 1988 | Food | Financial | Because of escalating production costs, the purchasing price of farm and farm-related products is raised systematically so that the purchasing price index rises by 14.5 percent by this year.[45] |

| 1988 | Food | Policy | Urban residents receive lump subsidies in lieu of the subsidies on products to help them purchase animal proteins at open market prices.[46] |

| 1990 | Food | Production | The total amounts of meat, eggs, milk and fish produced are 28.57, 7.94, 4.75 and 12.37 million tons, respectively. These outputs represent increases of 48,3 percent, 48.6 percent, 64,2 percent and 75,5 percent, respectively, over 1985 production. The increases allow a substantial improvement in the dietary patterns of urban and rural people. The annual per caput supply of meat, eggs and aquatic products is 13 kg higher in 1990 than in 1984.[45] |

| 1990 | Food | Production | The grain output is reported at 446.2 million tons, or 393.1 kg per capita.[45] |

| 1990 | Food | Policy | The State Council sets up a national specific grain reserve to improve the system gradually at the national, provincial, municipal and autonomous-region levels. All the surplus grain (that remaining after the contracted purchase) produced by the farmers that is not absorbed by the market is purchased. A protective minimum price is established for the benefit of the peasants. A leading group is responsible for the overall planning and managing of national specific grain reserve matters, and the Bureau of the Grain Reserve is initiated for national grain management. This system allows the state to purchase grain through the specific reserve as well as contracting and solves the peasants' problem of selling surplus grain after a bumper harvest. Because of this specific grain reserve, the supply of staples would be basically guaranteed for areas of the country that were flooded in 1991.[45] |

| 1990 | Food | Consumption | Meat consumption starts declining in rural areas. This is followed by an increased consumption of fish and shrimp products.[46] |

| 1990–2000 | Food | Production | Vegetable production in China increases from 67 to 141 kcals/capita/day in the period.[8] |

| 1991 | Food | Program launch | The National Program for Ten-Year Planning of the National Economy and Social Development and the Eighth Five-Year Plan are issued by the Chinese Government. These point to goals for the year 2000: "Based on the increase of income of the inhabitants, the food consumption of urban and rural people will be further raised in both quality and quantity, and the consumption of meat, eggs, milk, aquatic products and fruits will rise to some extent..." Nutritional status is officially incorporated into the national economic and social development plan.[45] |

| 1991 | Food | Policy | The price of grain and edible oil on ration is readjusted by a large margin for the first time since the mid-1960s. The price of grain is raised by 70 percent, and the price of edible oil almost doubles.[45] |

| 1991 | Food | Consumption | Meat consumption by urban households starts declining, while fish consumption starts increasing steadily.[46] |

| 1991–1995 | Food | Cost | China suffers from inflation and rapid price increases for food products. Consumer price index for red meat, poultry and eggs increases more than 40 percent in 1994 and more than 25 % in 1995.[46] |

| 1991–1997 | Food | Consumption | Mean intakes of energy decline from 101.8 percent of the Chinese recommended daily allowance to 95.2 percent, with means below the RDA in rural (92 percent) but not urban (102.7 percent) residents. In the same period, mean intakes of dietary fats increase from 21.8 to 27.7 percent of energy. Mean intakes of animal foods (meats and poultry, fish and eggs) increase by about 25 percent, from 105.6 to 131.6 g/day.[8] |

| 1992 | Food | Consumption | Cereal consumption increases to 645.9 grams per day, of which 15.9% are coarse grains (e.g., corn, millet, oatmeal), down from 50.4% in 1978 and 70.0% in 1952.[5] "The findings from the 28 provinces surveyed in 1992 showed that the average daily per capita energy intake varied from 1913 kcal in Hainan to 2720 kcal in Anhui."[53] |

| 1992 | Nutrition | Intake | Daily energy intake of urban residents amount to 2,395 kilocalories per reference person, which is 101 kilocalories higher than that of the rural population.[55] |

| 1992–1996 | Food | Consumption | Per capita urban pork consumption falls from 19.7 kilograms to 18.9, whereas per capita rural pork consumption rises from 11 kilograms to 12.2.[46] |

| 1992–1997 | Food | Production | Grain production rises from 442 million tons to 493 million.[46] |

| 1993 | Food | Policy | The Chinese government abolishes the 40-year-old grain rationing system, leading to more than 90 percent of all annual agricultural produce to be sold at market-determined prices.[9] |

| 1994 | Food | Policy | The Chinese government starts instituting a number of policy changes aimed at limiting grain importation and increasing economic stability.[9] |

| 1995 | Food | Policy | The central government delegates the primary responsibility of maintaining the regional balance of food supply, demand and reserves to provincial governors.[6] |

| 1995 | Food | Consumption | Urban households allocate about a half of their living expenditure to food, 23 percent of which is spent on red meat and poultry, while 7 percent is spent on aquatic products.[46] |

| 1995 | Food | Literature | United States environmental analyst Lester R. Brown publishes book Who Will Feed China?. Brown announces that if China can not feed its population, its food problem would potentially result in a global starvation.[6] |

| 1995 | Food | Policy | The "Governor's Grain Bag Responsibility System" is instituted, holding provincial governors responsible for balancing grain supply and demand and stabilizing grain prices in their provinces.[9] |

| 1995 | Food | Production | China reaches its target of 95 per cent food self-sufficiency.[6] |

| 1995 | Food | International trade | Chinese exports account for more than 11% of the world aquatic market.[46] |

| 1995 | Nutrition | Obesity | A policy asks schools to emphasize physical education as well as classroom learning, to promote higher levels of activity and help reduce early obesity.[8] |

| 1995–1999 | Food | International trade | Imports of French fries from the United States increases tenfold in the period.[8] |

| 1996 | Food | Infrastructure | China has roughly 700 dairy processing plants.[46] |

| 1997 | Nutrition | Intake | It is reported that more than 50 percent of adults living in all urbanized areas have high-fat diets.[8] |

| 1997 | Nutrition | Program launch | A National Plan of Nutrition Action is developed, involving intersectoral cooperation between policy-makers in the health and agriculture ministries, as well as other institutes involved in nutrition and food hygiene.[8] |

| 1997 | Food | Production | Milk supplies in the country are greater than demand and serious overstocking occurs.[46] |

| 1999 | Food | Policy | The food market further liberalizes, with only limited government regulations, including the food purchase price guide and prescribed quantities of food reserves, remaining in force.[6] |

| 2000 | Nutrition | Literature | Chinese anthropologist Jun Jing publishes Feeding China’s Little Emperors, a collection of papers exploring the dietary patterns of children growing up in the post-Mao transition to a market economy, where children dictate up to 70% of a family’s spending. For the first time in Chinese history, children are able to express preferences for different foods instead of merely accepting what is presented to them on the dining table. Local and foreign food companies start to target both youths and the financially secure parents who want to give their children the best. Many children in wealthy urban areas develop preferences for fast foods and processed foods instead of the traditional Chinese cuisine, leading to an increased prevalence of childhood obesity.[7] |

| 2001 | Food | Distribution | Supermarkets account for 48 percent of urban food markets in China, an increase beyond 30 percent level in 1999.[8] |

| 2003–2005 | Nutrition | Undernutrition | About 120 million Chinese from poor areas are estimated to be undernourished in the period.[56] |

| 2004 | Food | Consumption | Based on the annual grain output, food consumption per capita reaches 350 kg in the year.[54] |

| 2005 | Food | Production | Aquaculture: China reports harvesting 32.4 million tons, more than 10 times that of the second-ranked nation, India, which reported 2.8 million tons.[57] |

| 2006 | Food | Infrastructure | Farmland in China totals about 130.04 million hectares, about 3.92 million less than 1978.[9] |

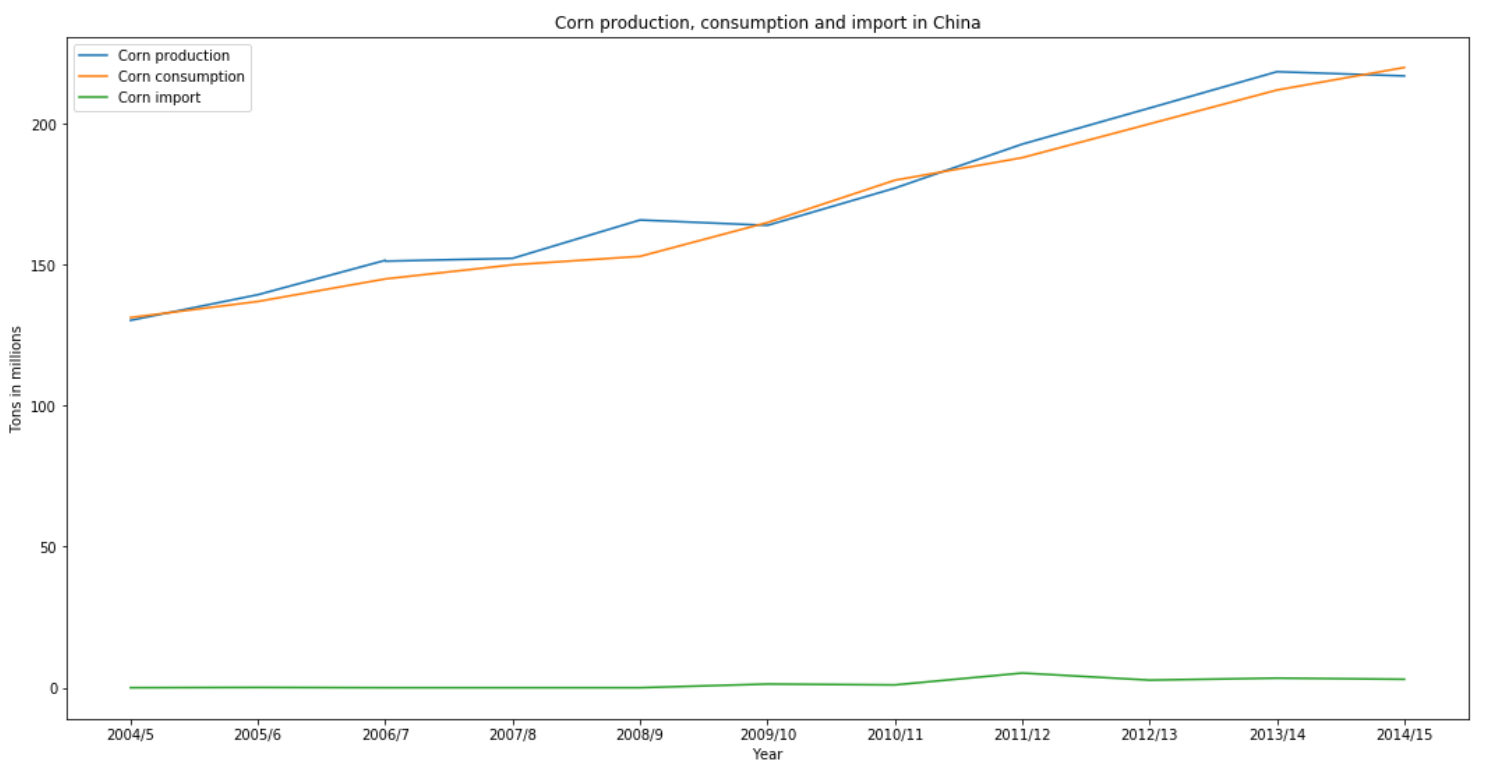

| 2008 | Food | International trade | China becomes a net importer of grains (namely sorghum, corn, distiller's dried grains with solubles, barley, wheat and rice).[6] |

| 2010 | Food | Consumption | Based on the annual grain output, food consumption per capita reaches 400 kg in the year.[54] |

| 2010–2013 | Nutrition | Overnutrition | The national prevalence of under-five overweight increases from 6.6% to 9.1%.[58] |

| 2011 | Nutrition | Intake | By this time, the average Chinese per capita daily calorie consumption is higher than that of Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Also, China's levels of plant-based calorie consumption are marginally lower than those in the United States, but animal-based calorie consumption still trails by 30%.[6] |

| 2012 | Food | International trade | China becomes the largest global importer of food and beverages.[6] |

| 2013 | Food | Consumption | By this time, the average Chinese person consumes approximately 57kg of meat per year, of which 71 per cent is pork.[6] |

| 2013 | Food | Production | China uses 364kg of fertilizer per hectare of arable land, higher than other major agricultural countries, including India(158kg/ha), the European Union (156kg/ha), Brazil (175kg/ha), the United States (132kg/ha), Canada (88kg/ha), Australia (51kg/ha) and Argentina (36kg(ha).[6] |

| 2013 | Food | Administration | The State Food and Drug Administration is upgraded to ministerial level and renamed the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA).[6] |

| 2013 | Food | Administration | The third plenum of the 18th Congress proposes policies to strenghten land rights in order to increase rural incomes.[6] |

| 2014 | Food | Production | Over 300 Chinese farming enterprises have investments across 46 different countries.[6] |

| 2014 | Nutrition | Statistics | Malnutrition is reported at less than 12% of the population.[52] |

| 2015 | Food | Production | Based on the annual grain output, food consumption per capita reaches 450 kg in the year.[54] |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

- [1] (for visual data)

- [2] (for visual data)

- [3] (for visual data)

- [4] (for visual data at page 11)

- [5] (for visual data at page 51)

- [6] (for visual data)

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "Chinese food and cuisine". Google Trends. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ "Malnutrition in India and China". Google Trends. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ Ó Gráda, Cormac. Famine: A Short History.

- ↑ El-Tawil, Anwar. Optimum Society: Will It Happen One Day?.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Du, Shufa; Wang, Huijun; Zhang, Bing; Zhai, Fengying; Popkin, Barry M. "China in the period of transition from scarcity and extensive undernutrition to emerging nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases, 1949–1992". PMID 24341754. doi:10.1111/obr.12122. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Tubilewicz, Czeslaw. Critical Issues in Contemporary China: Unity, Stability and Development.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Nutrition Transition in Chinese Communities". todaysdietitian.com. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Globalization of Food Systems in Developing Countries: Impact on Food Security and Nutrition (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations ed.).

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 IBP, Inc. China Agricultural Laws and Regulations Handbook Volume 1 Strategic Information and Basic Laws.

- ↑ Bredenkamp, Caryn. Health Reform, Population Policy and Child Nutritional Status in China.

- ↑ Wildman, RP; Gu, D; Muntner, P; Wu, X; Reynolds, K; Duan, X; Chen, CS; Huang, G; Bazzano, LA; He, J. "Trends in overweight and obesity in Chinese adults: between 1991 and 1999-2000.". PMID 18388899. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.208.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 "The History Of Chinese Nutrition". koosacupuncture.com. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The Story of Soy: From Wild Vine to Soy Burger.". eatingchina.com. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ The History of China.

- ↑ Jack N. Losso; Fereidoon Shahidi; Debasis Bagchi (2007). Anti-angiogenic functional and medicinal foods. CRC Press. p. 102. ISBN 1-57444-445-X.

- ↑ "CHINESE-IRANIAN RELATIONS viii. Persian Language and Literature in China". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ↑ Ferreyra, Eduardo. "Fearfull Famines of the Past". mitosyfraudes.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ↑ Jacobson, Judy. A Field Guide for Genealogists.

- ↑ The Illusory Boundary: Environment and Technology in History (Martin Reuss, Stephen H. Cutcliffe ed.).

- ↑ "North China famine, 1876-79". disasterhistory.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Edgerton-Tarpley, Kathryn. Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China.

- ↑ Sullivan, Lawrence R.; Liu-Sullivan, Nancy Y. Historical Dictionary of Science and Technology in Modern China.

- ↑ "CHINA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY RANKING". smartinternchina.com. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ↑ "History". en.cau.edu.cn. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ↑ Dianda, Bas. Political Routes to Starvation: Why Does Famine Kill?.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief (K. Bradley Penuel, Matt Statler ed.).

- ↑ "The Qing Dynasty — China's Last Dynasty". chinahighlights.com. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ "Chinese Famine (1907)". sk.sagepub.com. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Baker, O. E. "Agriculture and the Future of China". doi:10.2307/20028629.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China: Volume 14, The People's Republic, Part 1, The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949-1965 (Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank, Denis C. Twitchett ed.).

- ↑ FULLER, PIERRE. "North China Famine Revisited: Unsung Native Relief in the Warlord Era, 1920–1921". doi:10.1017/s0026749x12000534.

- ↑ "North China famine, 1920-21". disasterhistory.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ "Communism in China". cs.stanford.edu. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ↑ Vermeer, Eduard B. Economic Development in Provincial China: The Central Shaanxi Since 1930.

- ↑ "Northwest China famine, 1928-30". disasterhistory.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ "Perspectives on Environmental History in China". Journal of Chinese History. doi:10.1017/jch.2018.4.

- ↑ Ohwofasa Akpeninor, James. Modern Concepts of Security.

- ↑ "Sichuan famine, 1936-37". disasterhistory.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Eslamian, Saeid; Eslamian, Faezeh A. Handbook of Drought and Water Scarcity: Environmental Impacts and Analysis of Drought and Water Scarcity.

- ↑ Simoons, Frederick J. Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry.

- ↑ Grada, Cormac O. Famine: A Short History.

- ↑ "30 dramatic images of the 1942 Henan famine". china-underground.com. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ "Memory, Loss". nytimes.com. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail. Women and China's Revolutions.

- ↑ 45.00 45.01 45.02 45.03 45.04 45.05 45.06 45.07 45.08 45.09 45.10 45.11 45.12 45.13 45.14 45.15 45.16 45.17 "Food consumption and nutritional status in China". fao.org. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ 46.00 46.01 46.02 46.03 46.04 46.05 46.06 46.07 46.08 46.09 46.10 46.11 46.12 46.13 46.14 46.15 46.16 46.17 46.18 46.19 China Situation and Outlook Series 1998.

- ↑ Smil, Vaclav. "China's great famine: 40 years later". PMC 1127087

. PMID 10600969. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619.

. PMID 10600969. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619.

- ↑ "THE GREAT CHINESE FAMINE". alphahistory.com. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ↑ "China's Great Famine: A mission to expose the truth". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ↑ Kai‐sing Kung, James; Yifu Lin, Justin. "The Causes of China's Great Leap Famine, 1959–1961". Economic Development and Cultural Change. The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.1086/380584.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Yao, Shujie. Agricultural Reforms and Grain Production in China.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "The hungry and forgotten". The Economist. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "China". fao.org. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 Cui, Kai; Shoemaker, Sharon P. "A look at food security in China". nature.com. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ Riskin, Carl; Renwei, Zhao; Shih, Li. China's Retreat from Equality: Income Distribution and Economic Transition.

- ↑ "China: Improving nutrition and food safety for China's most vulnerable women and children". mdgfund.org. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ FAO Fact sheet: Aquaculture in China and Asia

- ↑ "Malnutrition burden". globalnutritionreport.org. Retrieved 3 December 2019.