Timeline of immigration detention in the United States

This timeline covers immigration detention in the United States.

It is a complement to the timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States and timeline of immigrant processing and visa policy in the United States.

See also List of detention sites in the United States for a list of detention centers.

Visual data

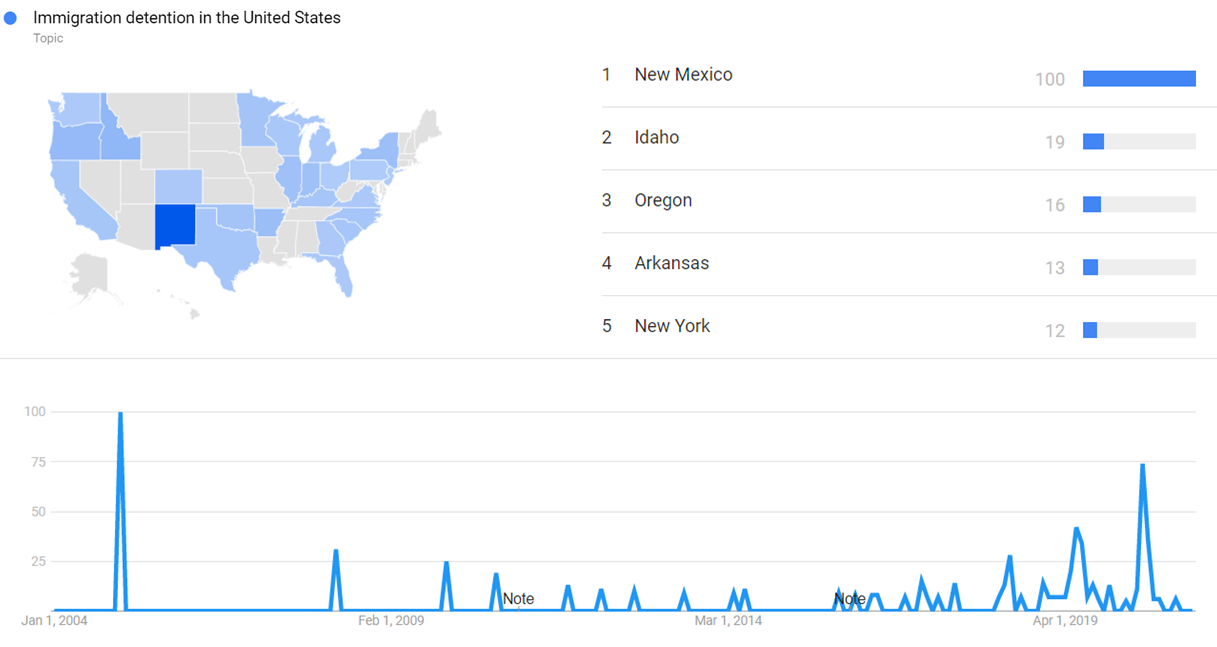

Google Trends

The image below shows Google Trends data in United States for Immigration detention in the United States (Topic) from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by state and displayed on map.[1]

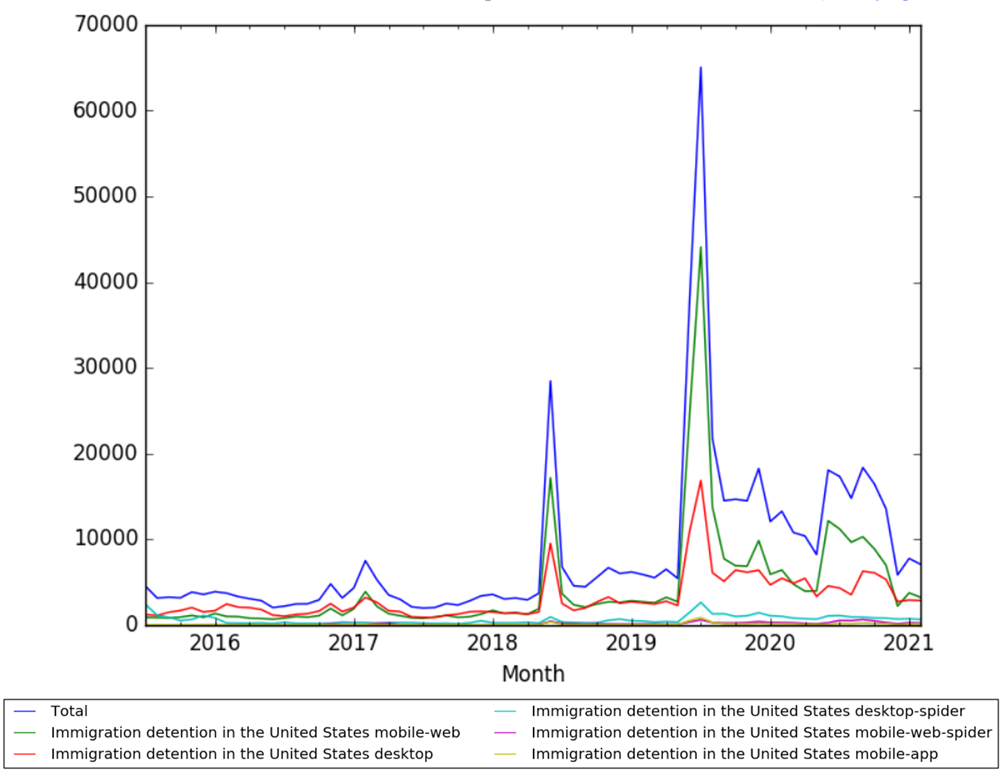

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Immigration detention in the United States, on desktop, mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app from July 2015; to February 2021.[2]

Full timeline

For the affected agencies column: ICE is shorthand for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; CBP is shorthand for U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

| Year | Month and date (if available) | Entity type | Event type | Affected agencies (past, and present equivalents) | Details | U.S. state (if applicable) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1892 | Immigration inspection station | Start | Ellis Island becomes an immigration inspection station, handling immigrants arriving via the Atlantic. Immigrants could be temporarily detained upon arrival for closer examination, or to hold till they are deported. | Federally owned, but near New York | Ellis Island | ||

| 1902 | Immigration inspection station | New functionality | The Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital is opened. It is both a general hospital and a contagious disease hospital. It also serves as a detention facility for new immigrants deemed unfit to enter the United States or held back for further examination. | Federally owned, but near New York | Ellis Island | ||

| 1910 | Immigration inspection station | Start | Angel Island Immigration Station, an immigrant inspection facility with a detention center, opens for operations. It handles immigrants arriving via the Pacific. | California | Angel Island | ||

| 1984 | January 22 | Detention center, detention contractors | Start | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | The Houston Processing Center opens at the site of the Olympic Hotel on I-45 North between Tidwell and Parker in Houston, Texas, processing 87 people. It is operated by the Corrections Corporation of America based on contract signed in 1983, and is the first detention center operated by a private contractor in the United States (and likely the earliest example of a private contract for operating a prison in the modern United States). Previously, ICE detention centers were managed by the Federal Bureau of Prisons.[3][4] | Texas | Houston Processing Center, Houston |

| 1984 | Detention center | Start | ICE | The Varick Street Federal Detention Facility opens in Manhattan, New York. The detention center would ultimately be closed in 2010 after protests by inmates and pressure from advocacy groups.[5] | New York | Varick Street Federal Detention Facility, Manhattan, New York City | |

| 1994 | August | Detention center (child detention) | Start | ICE | A detention center for juveniles opens in Leesport, Berks County, Pennsylvania. An article suggests that despite its distance from the border with Mexico, the location may have been chosen partly because of its convenience for government officials.[6] This detention center would become a family detention center in 2001.[7][8] | Pennsylvania | Berks County Detention Center, Leesport, Berks County |

| 1996 | April 24 | Legislation (adjacent) | Start | Executive branch | The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 104th United States Congress. Though not focused on migration, the Act has provisions related to the removal and exclusion of alien terrorists and modification of asylum procedures. It creates more reasons to detain migrants and is one of the factors responsible for an increase in immigration detention in the coming years.[9] | ||

| 1996 | September 30 | Legislation (landmark) | Start | Immigration and Naturalization Services | Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 104th United States Congress. It includes a number of provisions facilitating various forms of immigration enforcement that would be rolled out over the next two decades. One of its provisions that expands immigration detention is the addition of Immigration and Nationality Act Section 287(g), which allows state and local law enforcement officials to enforce federal immigration law on the condition that they are trained and monitored by ICE. | ||

| 1997 | January 28 | Agreement | Start | Executive branch | During the presidency of Bill Clinton, an agreement is reached regarding the permissible conditions for detaining child migrants, commonly called the Flores Agreement or Flores Settlement. This is a follow-up to the Supreme Court case Reno v. Flores. The three obligations identified for the government are: (1) The government is required to release children from immigration detention without unnecessary delay to, in order of preference, parents, other adult relatives, or licensed programs willing to accept custody. (2) If a suitable placement is not immediately available, the government is obligated to place children in the "least restrictive" setting appropriate to their age and any special needs. (3) The government must implement standards relating to the care and treatment of children in immigration detention.[10] | ||

| 1997 | Watchdog organization | Start | Detention Watch Network | Detention Watch Network is founded by the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc., Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project and Lutherans Immigration and Refugee Service to combat the explosive growth of the U.S. immigration detention system.[11] | |||

| 2000 | September | Detention standards | Start | ICE | A set of National Detention Standards (NDS) is issued that establishes "consistent conditions of confinement, program operations and management expectations" within the immigration detention system.[12] These would be the operational standards for detention centers to strive for until the introduction of new standards (PBNDS) in 2008.[13] | ||

| 2001 | March 3 | Detention center (family detention) | Repurposing | ICE | The Berks County Residential Center in Leesport, Berks County, Pennsylvania switches from being a detention center for youth to a family detention center; Berks would be the first family detention center in the US.[7][8][14] | Pennsylvania | Berks County Residential Center, Leesport, Berks County |

| 2001 | June 28 | Court ruling | Start | Executive branch | Zadvydas v. Davis is decided. The court rules that the plenary power doctrine does not authorize the indefinite detention of immigrants under order of deportation whom no other country will accept. To justify detention of immigrants for a period longer than six months, the government is required to show removal in the foreseeable future or special circumstances. | ||

| 2003 | March 1 | Organizational restructuring | Update | Immigration and Naturalization Services and U.S. Department of Homeland Security | The Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) (that was under the Department of Justice) is disbanded. Its functions are divided into three sub-agencies of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). | ||

| 2003 | Detention center | Start | ICE, Management and Training Corporation | The Willacy County Regional Detention Center opens for operations in Raymondville, Texas, operated by Management and Training Corporation under contract with the United States Marshal Service. | Texas | Willacy County Regional Detention Center, Raymondville | |

| 2004 | Detention center | Start | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | The Stewart Detention Center opens for operations in Lumpkin, Georgia. | Georgia | Stewart Detention Center, Lumpkin | |

| 2004 | Detention center | Start | ICE, GEO Group | The Northwest Detention Center opens for operations in Tacoma, Washington, operated by Correctional Services Corporation on contract with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. In 2005, Correctional Services Corporation would be purchased by GEO Group, so the management of th facility would transition to GEO Group. | Washington | Northwest Detention Center, Tacoma | |

| 2004 | December 17 | Detention capacity | Update | DHS (ICE) | The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 directs DHS to increase by 8,000 in each of the Fiscal Years from 2005 to 2010 the number of beds available for immigration detention and removal operations of DHS. It also requires priority for the use of these additional beds to the detention of individuals charged with removability or inadmissibility on security and related grounds.[15][16] | ||

| 2005 | Watchdog organization | Update | Detention Watch Network | Detention Watch Network relaunches as a dues-based membership network comprised of individuals and organizations working collectively on advocacy, public education and grassroots organizing efforts.[11] | |||

| 2005 | May | Detention center | Start | The South Texas Detention Facility, a privately operated prison, opens for operation in Pearsall, Texas as the Pearsall Immigration Detention Center. The prison houses people for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement as well as United States Marshal Service. | |||

| 2005 | October | Detention capacity | Proposal | DHS | Michael Chertoff, then Secretary of Homeland Security, calls for an increase in detention center capacity so that the United States immigration enforcement can hold people in detention between the time of catching them and the time of their immigration hearings, and does not need to resort to catch and release.[17] | ||

| 2006 | May | Detention center (family detention) | Start | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | The T. Don Hutto Family Residential Center starts operations as a family detention center on the site of a former private prison operated by the same operating company (Corrections Corporation of America). Its opening is motivated by a desire to increase detention capacity to be able to end "catch-and-release", and family detention in particular is promoted as an alterative to family separation (where parents are detained separately from children).[18][19][20] | Texas | T. Don Hutto Family Residential Center, Taylor, Williamson County |

| 2006 | July | Chertoff indicates in House committee testimony that an infusion of funding for more immigration detention has allowed DHS to detain almost all non-Mexican illegal immigrants.[21] | |||||

| 2006 | October 4 | Detention capacity | Update | DHS/ICE | When signing the DHS Appropriations Act of 2007, then-President George W. Bush notes that the funding in the Act will allow the addition of at least 6,700 new beds in detention centers, which would help continue to cut down on the use of catch-and-release policies.[22][15] | ||

| 2007 | March | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic), American Civil Liberties Union | The American Civil Liberties Union, University of Texas immigration law clinic, and the law firm LeBouef, Lamb, Greene & MacRae, file a lawsuit against DHS secretary Michael Chertoff and the immigration officials who oversee Hutto, alleging that the conditions at Hutto for children violate the Flores settlement. This would lead to a settlement in August 2007 to improve conditions, and an update in August 2009 with a plan to end family detention at Hutto.[19][23] | Texas | T. Don Hutto Family Residential Center, Taylor, Williamson County |

| 2007 | June 8 | Detention capacity | Update | DHS/ICE | In a report accompanying the DHS Appropriations Act of 2008, the House Committee on Appropriations writes that it supports ICE's requested funding for increasing its detention capacity from 27,500 beds to 28,450 beds (an incrase of 950), based on written and oral statements that this increase is sufficient to maintain ICE practice of "repatriating all illegal crossers apprehended at the borders."[24][15] | ||

| 2007 | July 6 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Government Accountability Office (GAO) | A report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) covering 23 detention centers shows significant telephone access problems but no pattern of noncompliance for other standards GAO reviewed.[25] | ||

| 2007 | Detention standards (monitoring) | Start | ICE, Nakamoto Group | ICE enters into a contract with the Nakamoto Group that is a "monthly monitoring contract" that "involved monthly technical assistance visits to mostly ICE detention facilities and included full-time technicall assistance compliance reviewers at the forty largest ICE detention facilities."[26] | |||

| 2008 | Detention standards | Update | ICE | ICE revises its National Detention Standards (NDS) released in 2000 to create a new set of standards called Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS), that, "developed in coordination with agency stakeholders, prescribe both the expected outcomes of each detention standard and the expected practices required to achieve them."[27] These would be the operational standards till the release of revised standards in 2011.[13] | |||

| 2008 | May 5 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | A New York Times article talks about deaths in ICE detention centers and the lack of accountability around them. It provides a detailed account of the death in ICE's Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey of Boubacar Bah, a 52-year-old tailor from Guinea.[28] | New Jersey | Elizabeth Detention Center, Elizabeth |

| 2008 | May 11 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE | Two articles in the Washington Post, published on the same day, look at cases of deaths in ICE detention. One is about Yusif Osman, a U.S. legal resident from Ghana detained on smuggling charges.[29] Another is about Francisco Castaneda from El Salvador, detained after drug possession charges.[30] Both had died at the Otay Mesa detention center in the San Diego region. | California | Otay Mesa detention center, San Diego |

| 2008 | June 4 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) covering 23 detention centers shows 3 of the centers to be in noncompliance with ICE's medical care standards at the time. It also finds 4 of the 23 centers to be in noncompliance with ICE's detainee grievance standards.[31] | ||

| 2008 | October | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE, New York City Bar Association | The New York City Bar Association receives a petition signed by 100 men in the Varick Street Federal Detention Facility in Manhattan, New York, describing "cramped, filthy quarters where dire medical needs were ignored and hungry prisoners were put to work for $1 a day" according to a New York Times article published in November 2009.[5] | New York | Varick Street Federal Detention Facility, Manhattan, New York City |

| 2009 | around March | Detention center | Start | ICE, Immigration Centers of America | A detention center is opened in Farmville, Virginia, through an agreement with the city of Farmville, amidst protests. The center is operated by Immigration Centers of America.[32] The National Immigrant Justice Center woud later list this as an example of "middleman contracting" considered improper under federal procurement law.[33] | ||

| 2009 | October 28 | Detention capacity | Update | ICE | The DHS Appropriations Act of 2009, for the first time, imposes a "bed mandate" on ICE based on language suggested by Senator Robert Byrd. Specifically, it says: "That funding made available under this heading shall maintain a level of not less than 33,400 detention beds through September 30, 2010."[34][35] The capacity would drop to 32,800 in Fiscal Year 2012 and increase to 34,000 in Fiscal Year 2015, and fluctuate further in the coming years.[15] There would later be comments by politicians claiming that the mandate requires ICE to fill the capacity every day, but fact-checking by the Washington Post[35] and PolitiFact[36] would reject that inference. | ||

| 2009 | November 2 | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE, New York City Bar Association (City Bar Justice Center) | A report by the City Bar Justice Center of the New York City Bar Association calls for all immigrant detainees to be provided with counsel.[5][37] Later in the month, an article in Fordham Law Review looks at the Varick Street detention facility as a case study in systematic barriers to legal representation.[38] | New York | Varick Street Federal Detention Facility, Manhattan, New York City |

| 2010 | February (approx) | Detention center | End | ICE | ICE announces its plans to close the Varick Street Federal Detention Facility in Manhattan, New York and relocate those currently held in it to prisons in New Jersey; Varick Street would only be used as a temporary holding location for a maximum of 12 hours per person. However, plans to close the place run into trouble due to challenges relocating people with medical and mental health challenges.[39] While there are some positive reactions, advocates push for deeper structural changes whereby people would be detained less; concerns are also raised about how relocating detainees would deprive them of their existing relationships with counsel based in New York.[40][41][42] | New York | Varick Street Federal Detention Facility, Manhattan, New York City |

| 2010 | Detention standards (monitoring) | Update | ICE, Nakamoto Group | ICE insources its monthly monitoring program of its largest detention centers, that had previously been handled by the Nakamoto Group on contract. Nakamoto Group would continue to be used by ICE for required annual inspections of detention centers based on ICE checklists.[26] | |||

| 2011 | Detention standards | Update | ICE | ICE releases an updated version of its Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) for its detention centers. ICE states that "PBNDS 2011 is crafted to improve medical and mental health services, increase access to legal services and religious opportunities, improve communication with detainees with limited English proficiency, improve the process for reporting and responding to complaints, and increase recreation and visitation."[43][13] | |||

| 2011 | August | Detention center | Start | ICE, GEO Group | The East Wing of the Adelanto Detention Center, a detention facility managed by GEO Group for ICE, opens for operation. The facility had previously been a state prison for adult male inmates before the GEO Group purchased it in 2010 and contracted with ICE in May 2011 to use it for immigration detention. The West Wing would open in July 2012. | California | Adelanto Detention Center, Adelanto, San Bernandino County |

| 2012 | March 13 | Detention center | Start | ICE, GEO Group | The Karnes County Civil Detention Center is opened by ICE, described as its first "designed-and-built civil detention center" and intended for low-risk, minimum-security adult male detainees. The 608-bed center is designed and is to be operated by GEO group. The agreement with Karnes County for the center had been entered into in December 2010. This is the first of several planned detention center creations and upgrades to make them feel less like prison. Immigrant rights groups have mixed reactions, with some seeing it as a step forward, and others expressing concerns about private operation of the prison as well as the continued use of detention centers instead of switching more completely to monitoring technology such as ankle bracelets.[44][45][46][47] | Texas | Karnes County Civil Detention Center, Karnes City, Karnes County |

| 2012 | Start | CIVIC (now Freedom for Immigrants) | Freedom for Immigrants is founded by Christina Fialho and Christina Mansfield as Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (CIVIC).[48] | ||||

| 2013 | February 22 | Detention center | Start | CBP (Border Patrol) | Clint Border Patrol Station opens as a migrant detention facility four miles north of the Mexico-U.S. border in Clint, Texas. The 51,000 sq. ft. facility replaces the 22,800 sq. ft. Fabens Border Patrol facility created in 1999.[49] Clint would be called "the public face of the chaos on America’s southern border" in a 2019 New York Times piece.[50] | Texas | Client Border Patrol Station, Clint |

| 2013 | November 20 (first report), December 6 (reissue) | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | The U.S. Government Accountability Office publishes a report on ICE's handling of sexual abuse risks in its detention centers, and makes several recommendations. The context is to gauge ICE's compliance with the Prison Rape Elimination Act.[51] | ||

| 2014 | Queer Detainee Empowerment Project | The Queer Detainee Empowerment Project (QDEP) is founded. Google dates the site to January 2014; the first Wayback Machine snapshot is from March 2014. | |||||

| 2014 | January 29 | Detention standards | ICE | The National Immigrant Justice Center conducts depositions of the chief of ICE's Detention Monitoring Unit and a former ICE contracting officer regarding ICE's contracting and inspections processes for immigration detention facilities.[52] | |||

| 2014 | June 20 | Detention center (family detention) | Start | DHS/ICE | DHS announces that it is setting up a temporary facility for detaining adults with children in expedited removal on the Artesia, New Mexico campus of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers. This comes amidst a surge in border-crossing, both by unaccompanied minors and by families with children.[53] The facility would generate controversy among the residents of Artesia.[54] | New Mexico | Artesia |

| 2014 | June 24 | Detention capacity | Update | DHS (both ICE and CBP) | DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson submits written testimony to the House Committee on Homeland Security detailing a multi-pronged response to the 2014 migrant surge, particularly the surge in child migrants. Part of the strategy includes increasing detention capacity for children and for families.[55][56] | ||

| 2014 | July}} | Detention center (child detention) | Start | CBP | The Ursula detention center (official name "Central Processing Center"), the largest detention center operated by Customs and Border Protection, opens for operation in McAllen, Texas at the site of a former Gmark warehouse, and extending the existing McAllen border station.[57][58][59] In June 2018, it would gain notoriety for the practice of keeping children in large cages made of chain-link fencing.[60] | Texas | Central Processing Center (aka Ursula Detention Center), McAllen |

| 2014 | August | Detention center (family detention) | Repurposing | ICE | The Karnes Family Residential Center is opened in Karnes County for family detention. The original detention center opened in Karnes in 2012 had been a low-security facility for adult males.[61] | Texas | Karnes Family Residential Center, Karnes City, Karnes County |

| 2014 | August 22 | Court case | Criticism/challenge | ICE | The lawsuit M.S.P.C. v. Johnson is filed against DHS/ICE for the conditions in the detention center at Artesia, New Mexico.[62][63] Followup investigations by ICE in response to the lawsuit would ultimately lead to an announcement of the closure of the detention center.[64] | New Mexico | Artesia |

| 2014 | October 10 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report on ICE detention standards and costs finds that ICE uses two methods to collect detention center cost data, and also that it has three sets of detention standards (2000 NDS, 2008 PBNDS, 2011 PBNDS) with each set of standards followed by at least some detention centers.[65][66] | ||

| 2014 | November 18 (announcement), December (execution) | Detention center (family detention) | End | DHS/ICE | DHS announces that the temporary family detention facility in Artesia, New Mexico will be shut down by the end of December. The detention center in Dilley, South Texas that is planned for a December opening is expected to make up the lost detention capacity.[67][68][64] | New Mexico | Artesia |

| 2014 | December 15 | Detention center (family detention) | Start | ICE, Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | The South Texas Family Residential Center opens in Dilley, South Texas. It has a capacity of 2,400 and is intended to detain mainly women and children from Central America. It is managed by the Corrections Corporation of America.[69][70] A Washington Post article in August 2016 would describe the setup of the center as based on a 4-year, $1 billion, no-bid contract, that circumvented the contract bidding process by using the city of Eloy, Arizona as a middleman.[71] | Texas | South Texas Family Residential Center, Dilley |

| 2014 – 2015 | December 16, 2014 – August 6, 2015; ICE policy change May 2015 | Court case | Criticism/challenge | ICE | The court case RILR v. Johnson is processed by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The plaintiffs are three mothers who came with their children, have asylum claims, and were locked up. The claim is that ICE has been locking up families -- including those with legitimate asylum claims -- as a way of deterring potential border-crossers, and that the "no-release" policy for detainees is a violation of federal immigration law and regulations, as well as the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. In May 2015, ICE announces that it will no longer consider general deterrence in detention decisions for families, upon which all parties agree to administratively close the case, with the possibility of reopening if ICE changes its policy.[72][73] | ||

| 2015 | May 13 | Detention standards, detention policy | Update | ICE | ICE announces a number of changes to its standards and practices around detention. One of the changes is to stop invoking deterrence effects as a factor in custody determinations for all families; this happens in the context of the RILR v. Johnson case that is seeking something similar. The creation of an Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers, consistent with the Federal Advisory Committee Act, is also announced. Other efforts to improve and monitor family detention practices are also announced.[74][75] | ||

| 2015 | September 17 | Detention standards (family detention) | Criticism/challenge | ICE, CBP, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights | A report by the United States Commission on Civil Rights titled "With Liberty and Justice for All: The State of Civil Rights at Immigration Detention Facilities" recommends an end to the practice of family detention, based on conditions in detention centers, violation of the Flores settlement conditions, and the lack of due process for detainees. The report is based on hearings in May and visits to the Karnes detention center and a processing center in Port Isabel.[76][77][66] | Texas | Karnes Family Residential Center, Karnes City, Karnes County; Port Isabel |

| 2015 | October 22 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE | The report "Lives In Peril: How Ineffective Inspections Make ICE Complicit In Detention Center Abuse" is published by the National Immigrant Justice Center and Detention Watch Network as part of The Immigration Detention Transparency And Human Rights Project. It is based on information collected through Freedom of Information Act requests filed by NIJC and a federal court order following three years of litigation.[78] | ||

| 2016 | Detention standards | Update | ICE | ICE revises its 2011 Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) to "ensure consistency with federal legal and regulatory requirements as well as prior ICE policies and policy statements." The revision is reflected through updates in the 2011 PBNDS on the ICE website, rather than a separate set of standards.[43] | |||

| 2016 | January 21 (announcement), January 27 (official notice) | Detention center (child detention) | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (PA DHS) | The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (PA DHS) issues notice that the licensing of the Berks County Residential Center to operate as a child detention facility is being revoked and will not be renewed.[79][80] The decision would be appealed in February;[81] PA DHS would issue reports of violations to the Berks County Residential Center in the years from 2016 to 2018.[82] | Pennsylvania | Berks County Residential Center, Leesport, Berks County |

| 2016 | February 29 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report reviews the current state of medical care at ICE's detention centers and makes recommendations that DHS accepts and plans to implement.[83] | ||

| 2016 | March 15 | Detention standards (monitoring) | Start | ICE, CBP, DHS OIG | The DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) releases a statement that it will conduct periodic unannounced inspections of CBP and ICE detention centers. This is in response to concerns raised by immigrant rights groups and complaints to the DHS OIG hotline about conditions in detentioon centers. The first inspection is done on the day of this statement.[84][85] | ||

| 2016 | October 27 | Detention center | Start | ICE | The Nation reports that the Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, Cibola County, New Mexico is reopening as an immigration detention center under contract with ICE, just a month after losing its contract as a minimum-security prison for the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the United States Marshals Service.[86] | New Mexico | Cibola County Correctional Center, Milan, Cibola County |

| 2016 | October 28 | Detention contractors | Update | Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) | Corrections Corporation of America, one of the two major private players in immigration detention (the other being GEO Group) rebrands as CoreCivic.[87] The renaming happens after years of bad press for the company around its management of detention facilities. | ||

| 2016 | November 21 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE | A report by the Southern Poverty Law Center finds that "detainees are routinely denied their due process rights and frequently endure inhumane conditions in isolated facilities that have little oversight from the federal government."[88] | ||

| 2017 | December 11 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, DHS OIG | DHS OIG publishes a report based in unanounced inspections of five detention centers, raising concerns about the treatment and care of ICE detainees at four of the five centers. The report includes one recommendation that ICE accepts and plans to implement.[89][85] | ||

| 2018 | January | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE | The Free Migration Project, National Immigration Project, and Aldea launch a coordinated legal effort to push for a shutdown of the Berks County Residential Center. This follows previous efforts including publications by the Center for Social Justice arguing that Pennsylvania's Department of Human Services has authority to shut down the center based on the revocation of its license.[90] A coalition of organizations called th Shut Down Berks Coalition is also created to coordinate advocacy work around pushing for a shutdown of the center.[91] | Pennsylvania | Berks County Residential Center, Leesport, Berks County |

| 2018 | April 18 | Detention statistics | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report identifies opportunities for ICE to improve its detention cost estimates.[92] | ||

| 2018 | June 14 | Detention center (temporary shelter) | Start | DHS/ICE | The Tornillo tent city appears to have started operation around this time, as a temporary shelter to detain migrants. It would be shut down in January 2019. | Texas | Tornillo tent city, Tornillo |

| 2018 | June 20 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE | A report titled "Code Red: The Fatal Consequences Of Dangerously Substandard Medical Care In Immigration Detention" critically reviews 15 deaths in ICE detention centers covered by the ICE in its detainee death reviews from December 2015 to April 2017. In addition to being highly critical of the poor standard of care, the report is also critical of ICE for its focus on adherence to checklists rather than on qualtiy of care. The report is jointly published by Human Rights Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Immigrant Justice Center, and Detention Watch Network.[85] | ||

| 2018 | June 26 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Nakamoto Group, DHS OIG | A report by the DHS Office of the Inspector General finds that neither of ICE's two types of inspection and monitoring processes (Office of Detention Oversight inspections, and inspections contracted out to the Nakamoto Group, a private company) ensure consistent compliance with detention standards, nor do they promote comprehensive deficiency corrections. Five recommendations are made to improve inspections, follow-up, and monitoring of ICE detention facilities, all of which are accepted by ICE with plans to implement.[93][94] | ||

| 2018 | September 27 | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GEO Group, DHS OIG | A report by the DHS Office of the Inspector General identifies several ways that the Adelanto Detention Center fails to meet ICE's Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) of 2011. ICE concurs with the recommendations and says it is implementing corrective action.[95][94] | California | Adelanto Detention Center, Adelanto, San Bernandino County |

| 2018 | November 15 (query), December 4 (response) | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, Nakamoto Group | A group of United States senators, including Elizabeth Warren (seemingly the leader), Bernie Sanders, and many others, ask Jennifer Nakamoto, the head of the Nakamoto Group, to address concerns about the thoroughness of the Nakamoto Group's inspections raised by recent DHS OIG reports.[96] Jennifer Nakamoto responds, contesting specific findings in some of the DHS OIG reports, as well as highlighting the limited mandate created by ICE of the Nakamoto Group's inspections, as well as the idea that the Nakamoto Group can only evaluate violations present at the time of the inspections.[26][94] | ||

| 2018 | Detention statistics | Start | ICE | ICE begins publishing detainee deaths within 90 days of each death. This is because "Congressional requirements described in the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Bill (2018) require ICE to make public all reports regarding an in-custody death within 90 days." The first reported death is for April 10, 2018.[97][98] Some immigrant justice and advocacy groups consider these reports to be shams that are more notifications of death than actual analyses of the cause of death.[99] | |||

| 2019 | January 29 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, DHS OIG | A report by the DHS Office of the Inspector General finds that "ICE does not adequately hold detention facility contractors accountable for not meeting performance standards." It makes five recommendations, all of which ICE accepts and proposes steps to implement.[100][94] | ||

| 2019 | October | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, CBP, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights | The United States Commission on Civil Rights releases a report tittled "Trauma at the Border: The Human Cost of Inhumane Immigration Policies"; Chapter 3 of the report goes into detail on detention standards. The report recommends ending Zero Tolerance, ending family separation, and not detaining peope who have been passed the credible fear test.[101] | ||

| 2019 | Detention standards | Start | ICE | ICE releases its 2019 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities. According to ICE: "These detention standards will apply to the approximately 45 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Intergovernmental Service Agreement (IGSA) facilities currently operating under the NDS, approximately 35 United States Marshals Service (USMS) facilities used by ICE and which ICE inspects against the NDS, as well as approximately 60 facilities (both IGSA and USMS) which do not reach the threshold for ICE annual inspections – generally those with an Average Daily Population of less than 10."[102] | |||

| 2020 | Detention standards | Start | ICE | ICE releases its 2020 Family Residential Standards.[103] | |||

| 2020 | March 24 (publication), April 21 (public release) | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, CBP, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report looks at care of pregnant women in CBP's and ICE's detention facilities. It find an overall compliance rate of 79% or higher, and a minority of complaints about care of pregnant women to be substantiated, with many claims hard to adjudicate.[104] | ||

| 2020 | April 20 onward | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE | Detainees at the Mesa Verde Detention Facility and the Yuba County Jail file a class action lawsuit against ICE in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, alleging that conditions of confinement at these facilities violated their constitutional rights by exposing them to unreasonable risks of infection and death from COVID-19. Preliminary injunctions are issued in June 2020 and December 2020.[105][106][107] | California | Mesa Verde Detention Facility, Bakersfield; Yuba County Jail, Marysville, Yuba County |

| 2020 | August 19 | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report concludes that ICE should enhance its use of facility oversight data and management of detainee complaints.[108] | ||

| 2021 | January 13 (publication), February 13 (public release) | Detention standards | Criticism/challenge | ICE, GAO | A U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggests actions ICE should take to improve planning, documentation, and oversight of detention facility contracts.[109][110] | ||

| 2021 | April 28 | Detention center | Criticism/challenge | ICE | The American Civil Liberties Union calls on DHS/ICE to shut down 39 ICE detention facilities, citing historically low occupancy rates and the costs of maintaining unused detention space.[111][110] In response, ICE says that the current low occupancy is due to having released detaines to comply with social distancing requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic, and future occupancy may be higher. ICE also explains that by making guaranteed payments even for unused beds, it is able to negotiate lower overall rates.[112] |

References

- ↑ "Immigration detention in the United States". Google Trends. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration detention in the United States". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Houston to host world's first museum dedicated to the private prison industry". Free Press Houston. October 15, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "The Rise and Decline of Private Prisons in the United States" (PDF). Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bernstein, Nina (November 1, 2009). "Immigrant Jail Tests U.S. View of Legal Access". New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Moyer, Merriell (June 16, 2017). "Why a PA county houses Central American immigrant families". Lebanon Daily News. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Shuey, Karen; Mekeel, David; Orozco, Anthony (June 24, 2018). "What you need to know about the residential center holding immigrant families in Berks County". Reading Eagle. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Deppen, Colin; Hughes, Sarah Ann (June 22, 2018). "Why PA's controversial Berks detention center for immigrant families is still open. A chorus of legislators and Philadelphia City Council are calling for the facility's closure, as pressure mounts on Gov. Tom Wolf.". BillyPenn. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Olivares, Mariela. "Intersectionality at the Intersection of Profiteering and Immigration Detention" (PDF). Nebraska Law Review. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "The Flores Settlement: A Brief History and Next Steps". Human Rights First. February 19, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "About Detention Watch Network". Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "2000 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "ICE Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. February 24, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Orozco, Anthony (March 31, 2021). "Lawyers, civic groups keep the pressure on Berks Family Residential Center". WHYY. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Immigration Detention Bed Quota Timeline" (PDF). January 1, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "S.2845 - Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004". September 23, 2004. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Chertoff: End 'Catch and Release' at Borders". Associated Press via Fox News. October 18, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ Cook, Terry (June 22, 2018). "Terry Cook: The long road to T. Don Hutto". Statesman News Network. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Talbot, Margaret (February 24, 2008). "The Lost Children. What do tougher detention policies mean for undocumented immigrant families?". New Yorker. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: T. Don Hutto Residential Center". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. March 24, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Chertoff hails end of let-go policy". Washington Times. July 28, 2006. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ "President Bush Signs Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act". October 4, 2006. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "ACLU challenges prison-like conditions at Hutto Detention Center". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Bill, 2008: report together with additional views" (PDF). June 8, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Alien Detention Standards: Telephone Access Problems Were Pervasive at Detention Facilities; Other Deficiencies Did Not Show a Pattern of Noncompliance". U.S. Government Accountability Office. July 6, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Attachment 3a - Response Letter from Nakamoto Group" (PDF). December 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "2008 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Bernstein, Nina (May 5, 2008). "Few Details on Immigrants Who Died in Custody". New York Times. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ Priest, Dana; Goldstein, Amy (May 11, 2008). "System of Neglect: As Tighter Immigration Policies Strain Federal Agencies, The Detainees in Their Care Often Pay a Heavy Cost". Washington Post. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ Priest, Dana; Goldstein, Amy (May 11, 2008). "E-Mails Show Attempt To 'Patch Up' a Case Of Medical Negligence". Washington Post. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Alien Detention Standards: Observations on the Adherence to ICE's Medical Standards in Detention Facilities". U.S. Government Accountability Office. June 4, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Ruff, Jamie (March 8, 2009). "Protest against immigrant detention center draws 150 in Farmville". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Policy Brief: The Dark Money Trail Behind Private Detention: Immigration Centers Of America-Farmville". National Immigrant Justice Center. October 7, 2019. Retrieved Julyl 26, 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2010" (PDF). October 28, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Lee, Michelle (May 15, 2015). "Clinton's inaccurate claim that immigrant detention facilities have a legal requirement to fill beds". Washington Post. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ Geng, Lucia (July 6, 2018). "ICE is required to fill 34,000 beds with detainees every single night and that number has only been increasing since 2009.". PolitiFact. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "NYC Bar Association Calls for Right to Counsel for Immigrant Detainees". City Bar Justice Center. November 2, 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Markowitz, Peter. "Barriers to Representation for Detained Immigrants Facing Deportation: Varick Street Detention Facility, A Case Study". Fordham Law Review. 78 (2).

- ↑ Bernstein, Nina (February 23, 2010). "Illness Hinders Plans to Close Immigration Jail". New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Statement to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Regarding Detainees at Varick Federal Detention Facility". February 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Hing, Julianne (February 25, 2010). "Varick Is Closing, But That's Not The Answer to Our Broken Detention System. The Varick Federal Detention Facility is days away from closure, and this should be good news.". ColorLines. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Varick Street Detention Facility to Close by End of February". March 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "2011 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "ICE opens its first-ever designed-and-built civil detention center. New facility in Texas opens today for low-risk, minimum security adult male detainees". March 13, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Sullivan, Laura (March 14, 2012). "Trying To Make Immigrant Detention Less Like Prison". NPR. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk; Eaton, Tim (March 13, 2012). "Detention for Immigrants That Looks Less Like Prison". New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Weissert (March 18, 2012). "Feds unveil reform-minded immigration site". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Who We Are". Freedom for Immigrants. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Schelby, Ronnie (March 7, 2013). "District Participates in New Border Patrol Station's Opening in Clint, Texas.". Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Romero, Simon; Kanno-Youngs, Zolan; Fernandez, Manny; Borunda, Daniel; Montes, Aaron; Dickerson, Caitlin (2019-07-06). "Hungry, Scared and Sick: Inside the Migrant Detention Center in Clint, Tex.". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention:Additional Actions Could Strengthen DHS Efforts to Address Sexual Abuse (Reissued on December 6, 2013)". U.S. Government Accountability Office. November 20, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Depositions Of ICE Experts". National Immigrant Justice Center. January 29, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: Artesia Temporary Facility for Adults With Children in Expedited Removal". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. June 20, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Carcamo, Cindy (September 13, 2014). "Detention center brings immigration debate to small-town New Mexico". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ "Written testimony of DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson for a House Committee on Homeland Security hearing titled "Dangerous Passage: The Growing Problem of Unaccompanied Children Crossing the Border"". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. June 24, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ "Family Detention in Berks County, Pennsylvania" (PDF). Human Rights First. August 1, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Crandall, Brett (July 1, 2014). "New McAllen facility to house 1,000 immigrant children". ValleyCentral. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Cuevas, Mayra; Ellis, Ralph (June 25, 2014). "Converted warehouse to process unaccompanied child migrants in Texas". CNN. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Margolis, Jason (August 4, 2014). "Conditions for migrants at a detention center in Texas are bleak and overcrowded". TheWorld. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Frej, Willa (2018-06-18). "These Are The Texas Immigration Center Photos Stirring Anti-Trump Outrage". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ Aguilar, Julián (December 6, 2016). "Immigration detention centers will continue operating despite judge's ruling. Two immigration detention centers in Texas will continue their day-to-day operations despite a Travis County judge's ruling last week that denied the facilities state licenses.". Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Carasik, Lauren (September 9, 2014). "The American "Deportation Mill". Immigrant families detained in Artesia, New Mexico, are suing the U.S. government". Boston Review. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Groups sue U.S. government over life-threatening deportation process against mothers and children escaping extreme violence in Central America". American Civil Liberties Union. August 22, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Ana Pottratz Acosta. "Sunlight is the Best Disinfectant: The Role of the Media in Shaping Immigration Policy". Mitchell Hamline Law Review. 44 (3).

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Management and Oversight of Facility Costs and Standards". U.S. Government Accountability Office. October 10, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Gruberg, Sharita (December 18, 2015). "How For-Profit Companies Are Driving Immigration Detention Policies". Center for American Progress. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Coleman, Michael (November 18, 2014). "Detention center in Artesia to close". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ Caldwell, Alicia (November 18, 2014). "U.S. to close immigrant detention center in Artesia". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Preston, Julia (December 15, 2014). "Detention Center Presented as Deterrent to Border Crossings". New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "South Texas immigration detention center set to open". 15 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ Harlan, Chico (August 14, 2016). "Inside the administration's $1 billion deal to detain Central American asylum seekers". Washington Post. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "RILR V. JOHNSON". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ↑ "A Tale of Two Immigration Judgments". Boston Review. March 31, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "ICE announces enhanced oversight for family residential centers". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. May 13, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Statement By Secretary Jeh C. Johnson On Family Residential Centers". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. June 24, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "With Liberty and Justice for All: The State of Civil Rights at Immigration Detention Facilities" (PDF). United States Commission on Civil Rights. September 17, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Muskal, Michael (September 18, 2015). "Detention conditions 'similar, if not worse' than migrants' home countries, report says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Lives In Peril: How Ineffective Inspections Make ICE Complicit In Detention Center Abuse". National Immigrant Justice Center. October 22, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ "The Department of Human Services is not renewing the certificate of compliance issued to the Berks County Commissioners to operate the Berks County Residential Center as a child residential facility" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. January 27, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania's legal authority to shut down Berks Family Detention Center". Center for Social Justice, Temple University Beasley School of Law. October 31, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "This is to acknowledge receipt of your request to appeal the Department's decision to NON-RENEW and REVOKE the license for Berks County Residential Center." (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. February 8, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Inspection/Violation Reports for BERKS COUNTY RESIDENTIAL CENTER". Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Management and Oversight of Detainee Medical Care". U.S. Government Accountability Office. February 29, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "DHS OIG To Periodically Inspect CBP and ICE Detention Facilities" (PDF). DHS Office of Inspector General. March 15, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 "Code Red: The Fatal Consequences Of Dangerously Substandard Medical Care In Immigration Detention". June 20, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ Seth Freed Wessler (October 27, 2016). "ICE Plans to Reopen the Very Same Private Prison the Feds Just Closed. Advocates cheered when the Justice Department began shuttering its private prisons. But immigration officials saw an opportunity.". The Nation. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Corrections Corporation of America Rebrands as CoreCivic". October 28, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Shadow Prisons: Immigrant Detention in the South". Southern Povery Law Center. November 21, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Concerns about ICE Detainee Treatment and Care at Detention Facilities" (PDF). DHS Office of Inspector General. December 11, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Berks Licensing Lawsuit". Free Migration Project. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Shut Down Berks Campaign". Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: Opportunities Exist to Improve Cost Estimates". U.S. Government Accountability Office. April 18, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "ICE's Inspections and Monitoring of Detention Facilities Do Not Lead to Sustained Compliance or Systemic Improvements" (PDF). DHS Office of the Inspector General. June 26, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 94.3 Noguchi, Yuki (July 17, 2019). "'No Meaningful Oversight': ICE Contractor Overlooked Problems At Detention Centers". NPR. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Management Alert – Issues Requiring Action at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, California" (PDF). DHS Office of the Inspector General. September 27, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Warren, Elizabeth (November 15, 2018). "Letter to Nakamoto Group re ICE Detention Facility Inspections" (PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Detainee Death Reporting". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "H. Rept. 115-239 - DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 2018". Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "ICE Releases Sham Immigrant Death Reports As It Dodges Accountability And Flouts Congressional Requirements". National Immigrant Justice Center. December 19, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "ICE Does Not Fully Use Contracting Tools to Hold Detention Facility Contractors Accountable for Failing to Meet Performance Standards" (PDF). DHS Office of Inspector General. January 29, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Trauma at the Border: The Human Cost of Inhumane Immigration Policies" (PDF). United States Commission on Civil Rights. October 1, 2019. Retrieved Julyl 27, 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "2019 National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Family Residential Standards 2020". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: Care of Pregnant Women in DHS Facilities". U.S. Government Accountability Office. March 24, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Zepeda Rivas v. Jennings (Immigration Detention)". ACLU Northern California. April 24, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Zepeda Rivas v. Jennings". Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Zepeda Rivas, et al. v. Jennings, et al.". Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: ICE Should Enhance Its Use of Facility Oversight Data and Management of Detainee Complaints". U.S. Government Accountability Office. August 19, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Immigration Detention: Actions Needed to Improve Planning, Documentation, and Oversight of Detention Facility Contracts". U.S. Governmnt Accountability Office. January 13, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Sganga, Nicole; Montoya-Galvez, Camilo (April 28, 2021). "ACLU calls on Biden administration to close dozens of ICE detention facilities". CBS News. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ "ACLU calls on Biden administration to shut down ice detention facilities. Low detention numbers pose unique opportunity to shut down architecture used to abuse and traumatize immigrants". American Civil Liberties Union. April 28, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ↑ Rose, Joel (April 28, 2021). "ACLU Calls On DHS To Close ICE Detention Centers, Citing High Cost Of Empty Beds". NPR. Retrieved July 4, 2021.