Timeline of immigrant processing and visa policy in the United States

This page provides a timeline of key events related to immigrant processing and visa policy of the United States. It focuses on laws, policies, and programs affecting pathways for authorized entry to the United States and long-term immigrant and non-immigrant statuses. It is complementary to the timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States.

The programs discussed here mostly come under the purview of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Office of Field Operations, and the U.S. Department of State agencies such as the Bureau of Consular Affairs. For the most part, it does not deal with programs under the purview of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement or the United States Border Patrol. There are some exceptions (such as the Student and Exchange Visitor Program, that is under the purview of ICE). To dive deeper into immigration enforcement, look at the timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States.

There are separate timelines with more detailed coverage of specific categories of visa policy: timeline of student visa policy in the United States and timeline of H-1B.

Big picture

| Time period | People in charge | Key developments |

|---|---|---|

| Before 1875 | There is no federal restriction on immigration during this time period. However, there are restrictions on naturalization (initially to free white persons of good moral character, and later to white and black persons) and there are provisions for deportation for sedition. There are also state-level regulations as well as private vigilante action against immigrants, such as against the Chinese in California, that we do not cover in this timeline. | |

| 1875 – 1907 | Presidents: many, most prominent being Chester A. Arthur and Theodore Roosevelt | The period sees the growth of federal immigration law to replace the state-level restrictions seen earlier. The Chinese are the main nationality that is explicitly singled out, but other legislation is mainly targeted at other East Asian immigration. Undesirable classes of immigrants begin to be enumerated, and border inspections begin. |

| 1907 – 1924 | Presidents: several, ending with Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge | The period sees the tightening of immigration, influenced partly by the Dillingham Commission; the Immigration Act of 1917 bars immigration from large parts of Asia, and the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924 also clamp down on immigration worldwide, with most regions other than Western Europe significantly affected. |

| 1925 – 1941 | Presidents: Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt | Immigration law remains largely unchanged during this period, as the United States transitions from an economic boom to the Great Depression in the United States and then enters World War II. |

| 1942 – 1964 | Presidents: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy | Immigration restrictions loosen slightly as the end of World War II heightens the value of international cooperation, and the United States emerges as one of two superpowers in the new world order. Legislations include the Magnuson Act of 1943, the Luce–Celler Act of 1946, and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (as well as temporary legislation such as the War Briides Act), but the basic framework of the restrictive policies of 1924 remains. Though not itself a significant relaxation of immigration, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 provides a legislative framework that would be modified by subsequent legislation. |

| 1965 – 1982 | Presidents: Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan (early years) | This period sees the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, a landmark legislation that significantly increases the permissible immigration levels from most places outside of Western Europe, by imposing per-country limits that are similar across countries (this still penalizes high-population countries such as India and China, but is overall much less restrictive than before). The United States Refugee Admissions Program begins. More temporary worker and fiance/spouse statuses are created. |

| 1983 – 1992 | Presidents: Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush | The period sees two landmark legislations: the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, that combines amnesty, enforcement, and a more defined temporary worker program, and the Immigration Act of 1990, that creates the contemporary framework for high-skilled immigration. |

| 1993 – 2000 | President: Bill Clinton | The period sees several legislations related to migration, including the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA), the American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA), the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act (AC21), Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, and Legal Immigration Family Equity Act (LIFE Act). Factors at play in these legislations include a desire to get more high-skilled workers, concerns about displacement of American workers, concerns about the impact of immigration on crime and welfare, and humanitarian responsibilities to immigrants who are victims of trafficking or have terrible home country conditions. |

| 2001 – 2008 | President: George W. Bush | The period sees some restructuring, partly in response to perceived need for more security after the September 11 attacks. Free trade agreements with Australia, Chile, and Singapore create new visa classes for citizens of those countries. |

Visual data

Google Trends

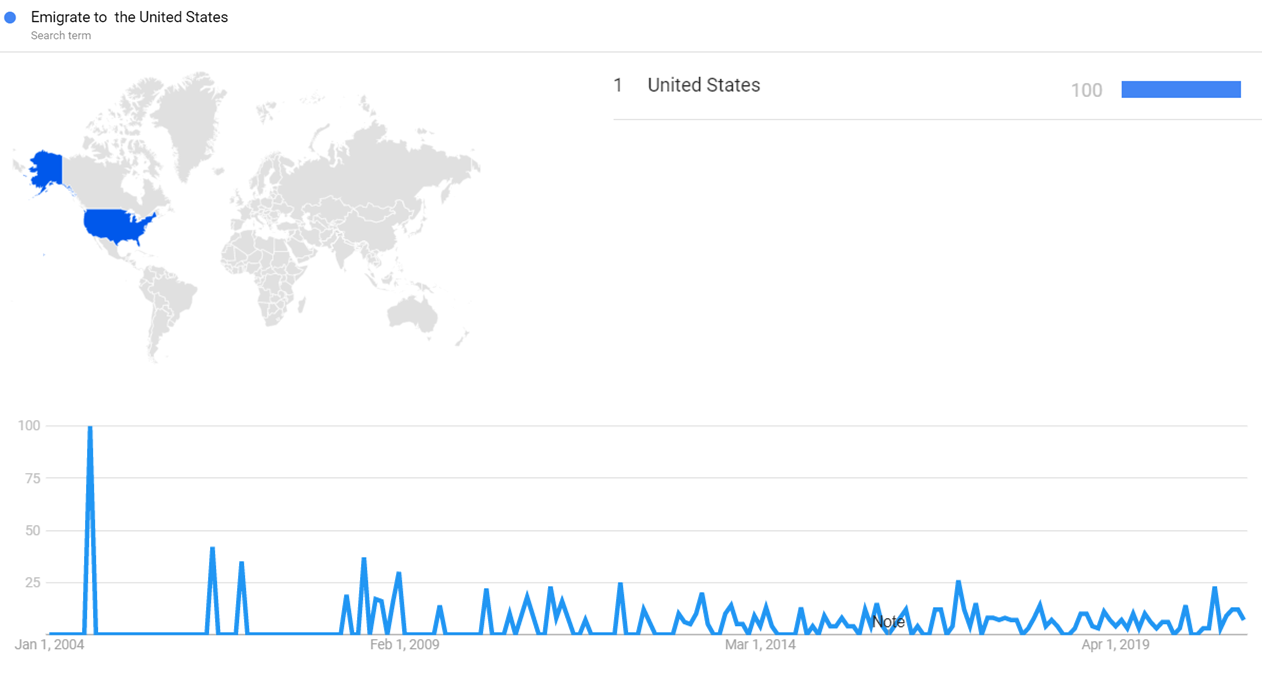

The image below shows Google Trends data for Emigrate to the United States (Search Term) from January 2004 to February 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[1]

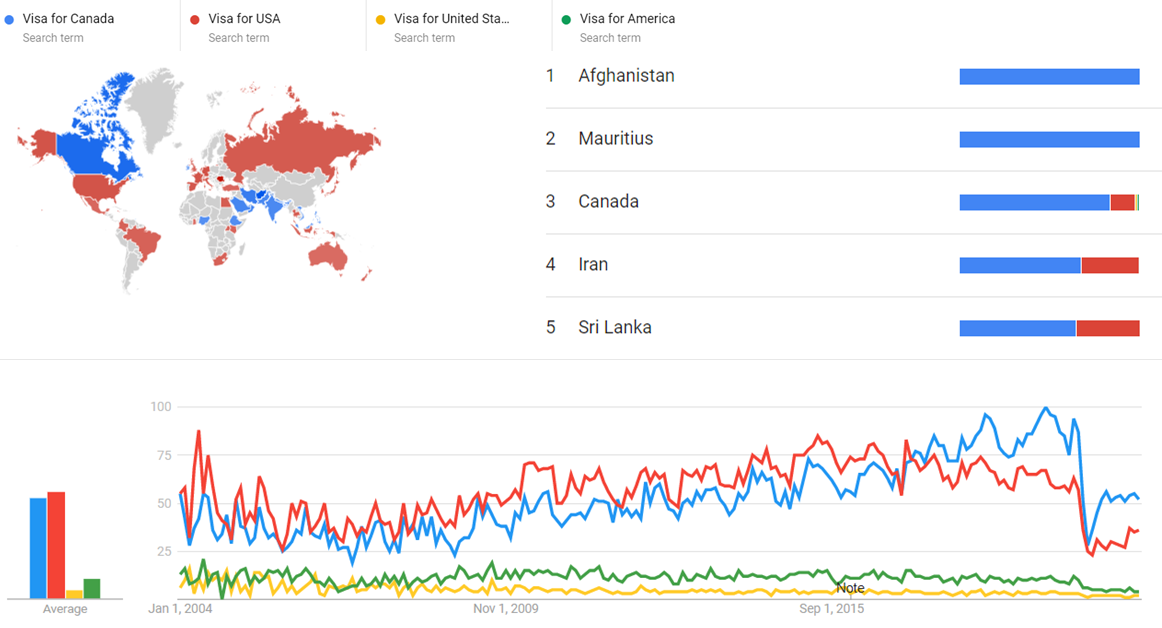

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Visa for Visa for Canada (Search term), Visa for USA (Search term), Visa for United States (Search term) and Visa for America (Search term), from March 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[2]

Google Ngram Viewer

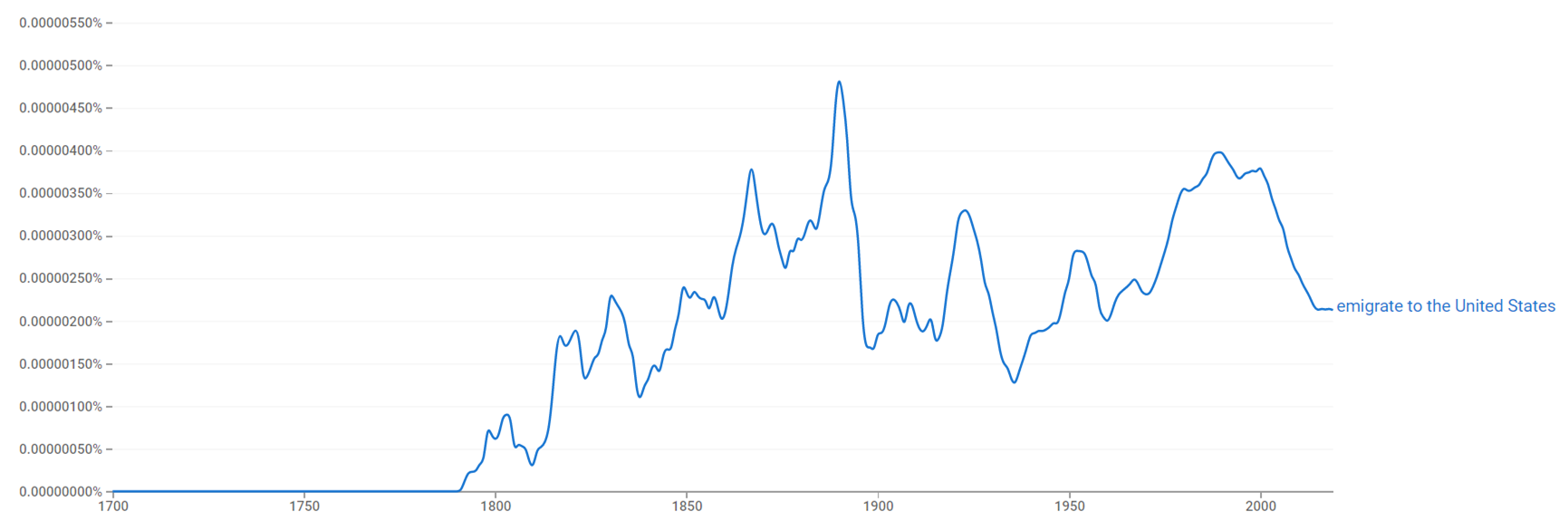

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Emigrate to the United States from 1700 to 2019. [3]

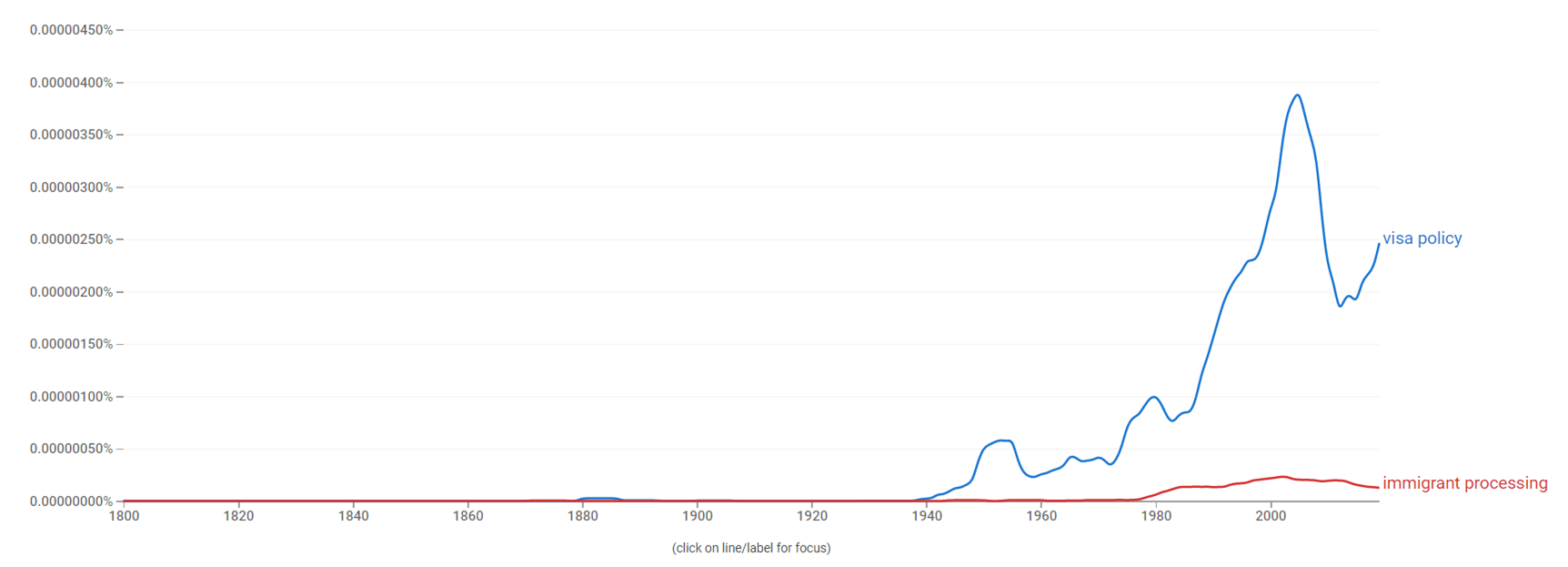

The chart bellow shows Google Ngram Viewer data for search strings "Visa policy" and "immigrant processing", from 1800 to 2019.[4]

Wikipedia Views

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date (if available) | Event type | Affected agencies (past, and present equivalents) | Visa letter for visa (usually nonimmigrant visa, unless specified otherwise) | Details | Source countries/regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Naturalization Act of 1790 is passed, specifying the rules for granting citizenship in the United States. Citizenship is limited to free white persons of good character. | |||

| 1798 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Alien and Sedition Acts (a total of four bills) are passed by the 5th United States Congress (that is Federalist-dominated) and signed into law by President John Adams. | |||

| 1819 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Steerage Act of 1819, also known as the Manifest of Immigrants Act, is passed. The Act regulates the conditions of travel on ships landing in the United States, and imposes a requirement that ships submit a manifest of all immigrants aboard. | |||

| 1855 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Carriage of Passengers Act of 1855 is passed, replacing the Steerage Act of 1819. | |||

| 1868 | July 28 | Treaty or trade agreement | Terms for what would later be known as the Burlingame Treaty between the United States and China are finalized. The treaty would be ratified by China in 1869. The Treaty grants most-favored-nation status to China, and allows free movement of people between the countries, but withholding the privilege of naturalization. | China | ||

| 1870 | July 14 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Naturalization Act of 1870 is signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant after passing both chambers of the 41st United States Congress. The Act extends the naturalization process to persons of African nativity and to persons of African descent (going beyond the Naturalization Act of 1790 that was limited to free white persons) while still excluding the Chinese and others. | ||

| 1875 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Page Act of 1875, the first United States federal restriction on immigration, passes. | |||

| 1881 | October 5 | Treaty or trade agreement | Executive branch | The Angell Treaty of 1880 is ratified. This modifies the previous Burlingame Treaty of 1868 between the United States and China, by temporarily suspending the migration of laborers (skilled and unskilled) from China. | China | |

| 1882 | May 6 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Chinese Exclusion Act is signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur after passing both chambers of the 47th United States Congress. This extends the suspension of Chinese migration started by the Angell treaty. | China | |

| 1882 | August 3 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1882 is signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur after passing both chambers of the 47th United States Congress. The Act mostly focuses on immigration enforcement but also creates new policies around excludable classes of immigrants. | ||

| 1888 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Scott Act is passed, after the failure of negotiations for the Bayard-Zhang Treaty. The Act applies the same criteria to re-entry of Chinese into the United States as were applied to initial entry by the Chinese Exclusion Act. | China | ||

| 1889 | Court case | Chae Chan Ping v. United States is decided by the United States Supreme Court against the petitioner. The case upholds the Scott Act and is one of the first of numerous court cases related to immigration policy and enforcement where the court rules in favor of the government. | China | |||

| 1891 | March 3 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1891 is signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison, after being passed by the 51st United States Congress. The Act expands the categories of excludable migrants, provides for more enforcement at land and sea borders, and adds authority to deport and penalties for people aiding and abetting migration.[5][6][7][8] It also creates an Office of Superintendent of Immigration, and places it under the Department of the Treasury.[9] | ||

| 1892 | May 5 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Geary Act, written by California Congressman Thomas J. Geary, becomes law. In addition to extending the Chinese Exclusion Act's prohibition on migration of Chinese laborers for another ten years, the Act also begins requiring Chinese in the United States to obtain and keep "certificates of residence" to demonstrate that they have been present in the United States since before immigration of Chinese laborers was banned. After Ny Look, a Chinese civil war veteran, is arrested for failure to obtain a certification, Judge Emile Henry Lacombe of the U.S. Circuit Court in the Southern District of New York, ruled in In re Ny Look that there are no deportation provisions in the law and Look could not be detained indefinitely therefore he should be released. This leads to the McCreary Amendment, giving Chinese an additional six months to register, and changing some of the requirements for certificates. | China | |

| 1895 | Organizational restructuring | Bureau of Immigration; modern equivalents are USCIS and CBP | The Office of Superintendent of Immigration is upgraded to the Bureau of Immigration.[9] | |||

| 1903 | March 3 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1903, also known as the Anarchist Exclusion Act, is signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt, after passing the 57th United States Congress. The Act codifies existing immigration law and also provides more grounds for excluding suspected anarchists. It has little practical effect. | ||

| 1903 | Organizational restructuring | Bureau of Immigration; modern equivalents are USCIS and CBP | The Bureau of Immigration is transferred to the newly created Department of Commerce and Labor.[9] | |||

| 1906 | September 27 | Legislation, organizational restructuring | Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization; modern equivalents are USCIS and CBP | The Naturalization Act of 1906 (revising the Naturalization Act of 1906) is signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt after passing both houses of th 59th United States Congress. The Act requires immigrants to learn English in order to naturalize, and also makes naturalization a federal responsibility. The Federal Naturalization Service is created, as the setting of policies for naturalization as well as the act of naturalization is now a federal responsibility. The Bureau of Immigration becomes the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization.[9] This is the last named "Naturalization Act" (further Acts in this domain would be called Nationality Acts). | ||

| 1907 | February 15 | Informal agreement | Executive branch | The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 is informally agreeed upon between the United States and Japan, whereby the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration and Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States. The agreement would never be ratified by United States Congress, and would eventually be superseded by the Immigration Act of 1924. | Japan | |

| 1907 | February 20 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1907 is signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt, after passing the 59th United States Congress. The Act provides more grounds for excluding immigrants. | ||

| 1907 | February | Commission | United States Congress | The United States Congress Joint Immigration Commission is formed by the United States Congress, to study the origin and consequences of recent immigration to the United States. It is known as the Dillingham Commission after its chairman, Republican Senator William P. Dillingham. The Commission completes its work in 1911, producing a 41-volume report. It would be influential in shaping the Immigration Act of 1917, the Emergency Quota Act, and the Immigration Act of 1924, and in particular, the National Origins Formula.[10] | ||

| 1913 | Organizational restructuring | Bureau of Immigration, Bureau of Naturalization; modern equivalents USCIS and CBP | The Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization is split into the Bureau of Immigration and the Bureau of Naturalization, and both are placed under the United States Department of Labor.[9] | |||

| 1917 | February 5 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1917 is passeed by both houses of the 64th United States Congress over the veto of President Woodrow Wilson. The legislation expands and consolidates the list of undesirables banned from entering the United States, including "illiterates" over the age of 16 as undesirables. It also creates an "Asiatic barred zone" from which immigration is not allowed; this includes China, British India, Afghanistan, Arabia, Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), the Malay States, the Dutch East Indies, the Soviet Union east of the Ural Mountains, and most Polynesian islands. The Asian exclusions do not apply to those working in certain professional occupations and their immediate families: "(1) Government officers, (2) ministers or religious teachers, (3) missionaries, (4) lawyers, (5) physicians, (6) chemists, (7) civil engineers, (8) teachers, (9) students, (10) authors, (11) artists, (12) merchants, and (13) travelers for curiosity or pleasure". | China, British India, Afghanistan, Arabia, Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), the Malay States, the Dutch East Indies, the Soviet Union east of the Ural Mountains, and most Polynesian islands | |

| 1918 | Legislation | Executive branch | A wartime requirement that visas are required for foreigners to enter the United States is made permanent.[11] (not clear which legislation made this permanent?) | |||

| 1918 | October 16 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1918, also known as the Alien Anarchists Exclusion Act of 1918, is signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson after passing the 65th United States Congress. | ||

| 1921 | May 19 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act, is signed into law by President Warren G. Harding after passing both chambers of the 67th United States Congress. It significantly reduces immigration quotas from countries around the world to 3% of the population of the country already present in the United States (this formula would later be called the National Origins Formula). | Differently affects different countries based on populations from them already in the United States | |

| 1923 | Court case | In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court of the United States rules that Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian Sikh man who self-identifies as Aryan, is ineligible to naturalize, as the law allows only "free white persons" and "aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent" to become United States citizens by naturalization. | India | |||

| 1924 | May 24 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Immigration Act of 1924, also called the Johnson–Reed Act, and including parts known as the National Origins Act and the Asian Exclusion Act, is signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge after passing both chambers of the 68th United States Congress. This updates the National Origins Formula to reduce the percentage to 2%. | Differently affects different countries based on populations from them already in the United States | |

| 1924 | Organizational restructuring | United States Border Patrol | United States Border Patrol is created within the Bureau of Immigration.[9] | |||

| 1933 | Organizational restructuring | Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS); modern equivalents are USCIS and CBP (and also ICE, though most ICE functions do not exist at the time) | The Bureau of Immigration and Bureau of Naturalization merge into the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).[9] | |||

| 1934 | March 24 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Tydings–McDuffie Act establishes the process for Philippines, then an American colony, to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. This also destroys freedom of movement from Philippines to the United States, as the now-to-be-independent Philippines is part of the Asiatic barred zone created by the Immigration Act of 1917 and reinforced by the Immigration Act of 1924. | Philippines | |

| 1935 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935 establishes a program to subsidize the return passage to the Philippines for Filipinos currently living in the United States. This is a followup to the Tydings–McDuffie Act that starts the process of Filipino independence and bans Filipino immigration. | Philippines | ||

| 1940 | October 14 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Nationality Act of 1940 is signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after passing both chambers of the 76th United States Congress. The Act revises "the existing nationality laws of the U.S. into a more complete nationality code" and provides details on who is eligible for citizenship via birth, who is eligible for citizenship via naturalization, who is not eligible for citizenship, and how citizenship could be lost or terminated. | ||

| 1940 | Organizational restructuring | Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS); modern equivalents are USCIS and CBP (and also ICE, though most ICE functions do not exist at the time) | The Immigration and Naturalization Service is transferred from the Department of Labor to the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), where it would stay for the rest of its life (till early 2003).[9] | |||

| 1943 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Magnuson Act becomes law. The Act repeals the Chinese Exclusion Act, but in practice immigration from China is still significantly restricted, as a quota of 105 annual Chinese immigrants is calculated through (flawed) use of the National Origins Formula of the Immigration Act of 1924. | China | ||

| 1945 | December 28 | Legislation | Executive branch | The War Brides Act is signed into law by President Harry Truman after passing both chambers of the 79th United States Congress. The law allows alien spouses, natural children, and adopted children of members of the United States Armed Forces, "if admissible," to enter the U.S. as non-quota immigrants after World War II. This mostly benefits Chinese, whose entry is allowed by the Magnuson Act, but who are subject to strict quotas. The Act would expire on December 31, 1948. | ||

| 1946 | June 29 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Alien Fiancées and Fiancés Act of 1946 is signed into law by President Harry Truman after passing both chambers of the 79th United States Congress. It extends the War Brides Act by eliminating barriers for Filipino and Indian war brides. A 1947 amendment would also remove barriers for Korean and Japanese war brides. The Act would expire on December 31, 1948. | Philippines, India (later also Korea, Japan) | |

| 1946 | July 2 | Legislation | Executive branch | The Luce–Celler Act of 1946 is signed into law by President Harry Truman after passing both chambers of the 79th United States Congress. Proposed by Republican Clare Booth Luce and Democrat Emanuel Celler in 1943, the Act allows annual immigration of 100 Filipinos and 100 Indians, and allows people of both nationalities to naturalize. The Act becomes law just two days before Filipino independence; without the Act, Filipino migration would have to stop completely upon Filipino independence. | Philippines, India | |

| 1952 | June 27 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | A (diplomat), B (business/tourist visitor), C (transit), D (crew), E (treaty trader, investor), F (student), G (foreign government representative), H (temporary worker), I (foreign press) | The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 becomes law after both chambers of the 82nd United States Congress vote to override the veto of President Harry S. Truman. This is the first of two big overhauls of the immigration system (the second being in 1965). Subsequent legislations would often be framed in terms of modifications to this legislation. Among other things, this Act begins the processing of formalizing non-immigrant classifications using letters of the alphabet; title I, section 15 defines the A to I nonimmigrant classifications.[12] | |

| 1952 | Organizational restructuring | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs; current equivalent: Bureau of Consular Affairs | The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 leads to the creation of the Bureau of Inspection, Security and Consular Affairs, which is responsible for issuing visas at foreign consulates to people who want to enter the United States. In 1954, the Bureau is renamed the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs. | |||

| 1961 | September 21 | Legislation | U.S. Department of State | J (exchange visitors) | The Fulbright–Hays Act of 1961, also known as the Mutual Exchange and Cultural Exchange Act of 1961 (MECEA), is signed into law by President John F. Kennedy after passing both chambers of the 87th United States Congress. The Act encourages mutual education and cultural exchange between the United States and other countries, and in particular, leads to the creation of the J-1 visa category.[13] | |

| 1965 | October 3 | Legislation (landmark) | Executive branch | The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act for its co-sponsors, is signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson after passing both chambers of the 89th United States Congress. The Act would go into effect on June 30, 1968. As of 2020, it is the most recent radical overhaul of the immigration system in the United States. | Differently affects different countries based on their population and existing migration flows | |

| 1966 | November 2 | Legislation | The Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA) is signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson after passing both chambers of the 89th United States Congress. The law applies to any native or citizen of Cuba who has been inspected and admitted or paroled into the United States after January 1, 1959 and has been physically present for at least one year; and is admissible to the United States as a permanent resident. A 1995 revision would create the wet feet, dry feet policy that would ultimately by ended by Barack Obama at the end of his presidency in January 2017. | Cuba | ||

| 1970 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services, U.S. Department of State | H-4, K, L | The H-4, K and L visas are created by a 1970 Amendment to the Immigration and Nationality Act.[14][15][16] | ||

| 1976 | October 20 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services | H (temporary workers) | The Eilberg Amendment, sponsored by Joshua Eilberg after lobbying by the Association of American Universities, is signed into law.[17] The legislation allows nonprofit research institutions to sponsor unlimited numbers of foreign nationals without having to meet previously required standards regarding wages and working conditions.[18][15] It would later be cited as a precedent for the Immigration Act of 1990.[19] | |

| 1979 | Organizational restructuring | U.S. Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs | The Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs is restructured: its security functions are moved to the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, and the organization is renamed te Bureau of Consular Affairs. | |||

| 1980 | Legislation | Executive branch | The 96th United States Congress passes the Refugee Act of 1980, standardizing the process of refugee resettlement. This leads to the creation of the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP). | |||

| 1981 | January 20 | Leadership change | Executive branch | Republican politician Ronald Reagan is sworn in as President of the United States. | ||

| 1981 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services | M (vocational course student) | Public Law 97-116, the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1981, is passed by the 97th United States Congress.[20] Among other things, these create a new M-1 visa for students of non-academic (vocational) courses.[21] | ||

| 1982 | February 22 | Leadership change | Immigration and Naturalization Services | Alan C. Nelson becomes the Comissioner of the INS, working under President Ronald Reagan.[22] | ||

| 1983 | January 9 | Organizational restructuring | Executive Office for Immigration Review, Board of Immigration Appeals, Immigration and Naturalization Services | The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is created as part of the U.S. Department of Justice. The EOIR combines two pre-existing functions: the Board of Immigration Appeals (also originally under the DOJ) and the Immigration Judge function (carried out previously by the INS, which was at the time under the DOJ).[23] | ||

| 1985 | February | Leadership change | U.S. Department of Justice | Edwin Meese becomes United States Attorney General.[24][25] The Attorney General heads the U.S. Department of Justice, and prior to the September 11 attacks, the INS was under the Department of Justice. | ||

| 1986 | November 6 | Legislation (landmark) | Immigration and Naturalization Services; current equivalent: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | H-2 (H-2A, H-2B; temporary workers) | The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, after passing both houses of the 99th United States Congress after three years of legislative back-and-forth. The key sponsors are Alan K. Simpson and Romano L. Mazzoli, so the act is also known as the Simpson–Mazzoli Act. This combines an amnesty for people who have been present in the United States for a while, a restructuring of the H-2 program splitting it into the H-2A (unlimited temporary agricultural workers) and H-2B (other temporary workers), and more resources into enforcement.[26] The Act also includes a provision for what would later become the Visa Waiver Program.[27] | |

| 1987 | October 21 | Deferred action | Immigration and Naturalization Services | Alan C. Nelson, INS Commissioner announces Family Fairness, a deferred action policy for children (and, in rare cases, spouses) of people eligible to legalie per the IRCA, to solve the problem of split-eligibility families.[28] | ||

| 1988 | July | Visas | United Kingdom | The United Kingdom becomes the first country to participate in the newly created Visa Waiver Program (VWP), a program for reciprocal visa-free travel between the United States and other countries. | ||

| 1988 | October 15 | Leadership change | U.S. Department of Justice | Dick Thornburgh becomes Attorney General, succeeding scandal-engulfed Edwin Meese. | ||

| 1988 | November 18 | Legislation (adjacent) | Executive branch | The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan after passing both chambers of the 100th United States Congress. The Act, though not focused on migration, introduces the concept of aggravated felony to refer to murder, federal drug trafficking, and illicit trafficking of certain firearms and destructive devices. Aggravated felonies are grounds for removal and exclusion of aliens.[29][30] | ||

| 1988 | Legislation | Executive branch | The American Homecoming Act is passed, giving preferential immigration status to children in Vietnam born of U.S. fathers. The Act would be implemented in 1989, and would operate via the Orderly Departure Program. | Vietnam | ||

| 1989 | January 20 | Leadership change | Executive branch | Republican politician and incumbent vice-president George H. W. Bush becomes President of the United States, succeeding Ronald Reagan. | ||

| 1989 | June 16 | Leadership change | Immigration and Naturalization Services | INS Commissioner Alan C. Nelson is fired, amidst clashes with Attorney General Dick Thornburgh who wants to bring the INS more firmly under his own control, as well as accusations against Nelson of mismanagement.[22][31][32] | ||

| 1990 | February 5 | Deferred action | Immigration and Naturalization Services | The Family Fairness policy is extended to spouses of IRCA-eligible people. The extension serves as a bridge to a legislation that is passed as part of the Immigration Act of 1990.[33][34] | ||

| 1990 | November 29 | Legislation (landmark) | Immigration and Naturalization Services | H-1 (H-1A, H-1B), O, P, Q, R; EB (immigrant visas) | The Immigration Act of 1990 is signed into law by President George H. W. Bush. While mostly focused on legal temporary and permanent immigration, some provisions of the Act are relevant to enforcement.[35][36] The main contributions of the Act include separation of H-1 into H-1A (for nurses) and H-1B (for other skilled workers), allowing for dual intent for H-1Bs (i.e., H-1B status can be held by people with pending green card applications).[37] The Act also formalizes employment-based immigration with the creation of employment-based preference categories (EB-1, EB-2, and EB-3 for employment-based green cards). The Act also creates the O, P, Q, and R nonimmigrant visa categories for outstanding scholars and cultural exchange visitors. The Q visa would be dubbed the "Disney visa" because of the role Disney plays in creating it, and the heavy use of it by Disney.[38][39] | |

| 1993 | January 20 | Leadership change | Executive branch | Democratic politician Bill Clinton becomes President of the United States, after defeating incumbent George H. W. Bush in elections. | ||

| 1993 | March 11 | Leadership change | U.S. Department of Justice | Janet Reno becomes Attorney General. | ||

| 1993 | October 18 | Leadership change | Immigration and Naturalization Services | Doris Meissner becomes INS Commissioner.[40][41] | ||

| 1994 | January 1 | Treaty or trade agreement | Executive branch | TN (free trade visa for Canada/Mexico) | The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) comes into force. The agreement is between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Though primarily pertaining to trade, the agreement also includes some provisions on facilitating easier movement across borders, and in particular leads to the TN visa. | |

| 1994 | March/April (announcement), July 26 (official start date) | Visas | U.S. Department of State | The National Visa Center opens at the site of a former Air Force base in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The NVC processes all approved immigrant visa petitions after they are received from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and retains them until the cases are ready for adjudication by a consular officer abroad.[42] | ||

| 1995 | Visas | U.S. Department of State | DV (immigrant visa category) | The first lottery of the current incarnation of the Diversity Immigrant Visa (Diversity Visa, DV) is conducted, in accordance with the Immigration Act of 1990. The DV succeeds three similar programs: the first-come first-serve NP-5 (1987 – 1989), lottery-based OP-1 (1989 – 1991), and AA-1 (1992 – 1994). Efforts to end the program would start in 2005, but the program would continue until 2020. Only people whose country of chargeability has sent fewer than 50,000 immigrants in the last 5 years (in the family-based and employment categories) are eligible for the DV lottery. | ||

| 1996 | April 24 | Legislation (adjacent) | Executive branch | The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 104th United States Congress. Though not focused on migration, the Act has provisions related to the removal and exclusion of alien terrorists and modification of asylum procedures. | ||

| 1996 | September 30 | Legislation (landmark) | Immigration and Naturalization Services | Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 104th United States Congress. It includes a number of provisions facilitating various forms of immigration enforcement that would be rolled out over the next two decades. | ||

| 1997 | November 19 | Legislation | The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 105th Unitd States Congress. | Nicaragua, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala; also, limited provisions for some Soviet Bloc countries | ||

| 1998 | October 21 | Legislation | H-1B | The American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA) is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 105th Unitd States Congress. | ||

| 1998 | October 21 | Legislation | The Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act (HRIFA) is signed into law by President Bill Clinton after passing both chambers of the 105th Unitd States Congress.[43] | Haiti | ||

| 2000 | October 17 | Legislation | H-1B | American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act (AC21). | ||

| 2000 | October 28 | Legislation | T, U | Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. This would lead to the creation of the T visa, a temporary status for people who are the victims of trafficking and slave-like conditions. The status could lead to permanent residency after a few years. It would also create the U visa that serves a similar purpose. | ||

| 2000 | December 21 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services; current equivalent United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | V, K-3, K-4 | The Legal Immigration Family Equity Act is passed. Among other things, the Act allows for the overlooking of unauthorized presence in the United States for people who have been in the queue for permanent residency for a long time. The Act primarily references immigrant processing functions now under USCIS rather than enforcement functions, but also contains some protection from removal proceedings. Specifically, protection from removal proceedings begins after the Form I-485 (green card application) is filed; people who are eligible for legalization in the future through this Act but are still in the queue may be subject to removal proceedings.[44][45][46] | |

| 2002 | September | Port of entry processing | CBP Office of Field Operations, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement | The National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) starts operating. This includes port-of-entry registration and domestic registration for certain non-citizens. | ||

| 2002 | November 25 | Organizational restructuring | U.S. Department of Homeland Security | The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) comes into formal existence. Eventually, the functions handled by the INS (which was under the Department of Justice) would move to the DHS. | ||

| 2003 | March 1 | Organizational restructuring | Immigration and Naturalization Services and U.S. Department of Homeland Security | The Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) (that was under the Department of Justice) is disbanded. Its functions are divided into three sub-agencies of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). | ||

| 2004 | Treaty or trade agreement | USCIS, U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs | H-1B1 | The Singapore–United States Free Trade Agreement and Chile–United States Free Trade Agreement becomes active. While mostly focused on trade, the agreement gives rise to the H-1B1 visa (available to people from Singapore and Chile), providing another option for people from the two countries who want to work in the United States. | ||

| 2004 | Legislation | USCIS, U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs | H-1B, L-1 | H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004 and L-1 Visa Reform Act of 2004 | ||

| 2004 | December 17 | Legislation | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs | The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act becomes effective. Title V of the Act, "Border protection, immigration, and visa matters", includes a section titled "Visa Requirements". Among other things, this codifies into law a Department of State rule from August 1, 2003 requiring most nonimmigrant visa applicants between the ages of 14 and 79 to have a face-to-face interview with a consular officer.[47] | ||

| 2005 | Treaty or trade agreement | USCIS, U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs | E-3 | The Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement becomes active. While pertaining mostly to trade, the Agreement also leads to the creation of the E-3 visa category, making it easier for people from Australia to come to the United States temporarily for work. | ||

| 2011 | January 10 | Visas | The Interview Waiver Program, where people applying for a visa renewal can skip the visa interview under some circumstances, is announced.[48] The program would roll out incrementally over the next several years until being suspended by President Donald Trump's Executive Order 13769. | |||

| 2011 | April 27 | Port of entry processing | US-VISIT is introduced by the Obama administration for port-of-entry processing, and the existing system (NSEERS) is indefinitely suspended. | |||

| 2013 | March 27 to May 21 | Port of entry processing | CBP Office of Field Operations | Form I-94 is made electronic at air and sea ports. The announcement in the Federal Register occurs on March 27,[49] and the rollout happens from April 30 to May 21.[50][51] | ||

| 2016 | Visas | The rules of the Visa Waiver Program (VWP) are modified so that now, a person who would otherwise qualify for visa-free entry under the VWP must still get a visa if that person has visited any country on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism on or after March 1, 2011.[52] | Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen | |||

| 2017 | January 27 | Executive order | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs, CBP Office of Field Operations | Newly elected United States President Donald Trump issues Executive Order 13769. This immediately suspends issuance of visas to people from the 7 countries listed at the time by DHS as State Sponsors of Terrorism. It also suspends the Interview Waiver Program[53][54][55] | Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen | |

| 2017 | March 6 | Executive order | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs, CBP Office of Field Operations | Newly elected United States President Donald Trump issues Executive Order 13780. This supersedes and refines Executive Order 13769, providing more detail on the ban of entry for people from the countries listed as State Sponsors of Terrorism. The list of affected countries and the nature of restriction continues to be modified. In particular, Presidential Proclamation 9645 (September 24, 2017) Presidential Proclamation 9723 (April 10, 2018), and Presidential Proclamation 9983 (February 21, 2020) modify the executive order. | ||

| 2017 | October 25 | Leadership change | USCIS | Lee Cissna becomes USCIS Director, replacing Leon Rodriguez, who had served as USCIS Director under the Obama administration.[56] According to a September 2018 profile in Politico, as the head of USCIS, Cissna has "transformed his agency into more of an enforcement body and less of a service provider."[57] | ||

| 2017 | December 6 | Leadership change | U.S. Department of Homeland Security | Kirstjen Nielsen assumes the office of Secretary of Homeland Security, replacing acting Secretary Elaine Duke.[58][59] According to CNN, the hiring of Nielsen is based on a strong positive recommendation from White House Chief of Staff John F. Kelly.[60] | ||

| 2017 – 2020 | Quota change | U.S. Department of State | Refugee admissions | Under President Donald Trump, the United States' refugee program is significantly pared back. Executive Order 13769 (January 27, 2017) puts a temporary moratorium on all refugee admissions. Refugee admissions are resumed in late October 2017, but refugees are not allowed from 11 countries, and other restrictions are added, causing a drop in the number of refugees. The administration further cuts the refugee quota in 2018 and 2019, and refugeee admissions are effectively halted in 2020 because Trump does not set a quota. Learn more at Immigration policy of Donald Trump#Travel ban and refugee suspension and Asylum in the United States. | ||

| 2019 | January 24 | Program rollout | U.S. Department of Homeland Security | Case processing, affecting asylum applications at the border | The U.S. Government introduces the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), colloquially known as the Remain in Mexico policy. With this policy, people who present themselves at land ports of entry (including those seeking asylum) or are caught crossing the border may be required to wait in Mexico, near the U.S. border, for their case to be adjudicated.[61] | |

| 2019 | April 7 | Leadership change | U.S. Department of Homeland Security | Kirstjen Nielsen resigns as Secretary of Homeland Security, with April 10 being her last day. Commentators attribute her resignation to Trump's desire to push harder on immigration enforcement, and his dissatisfaction with what Nielsen accomplished on that front, as well as her pushback against some of his demands. Trump's political advisor Stephen Miller is believed by commentators to be a key opponent of Nielsen in the White House.[60][62] Kevin McAleenan, then the Customs and Border Protection Commissioner, becomes the next Secretary of Homeland Security; Claire Grady, who would have otherwise been the person to assume the role, is forced by Donald Trump to resign at the same time as Nielsen so that McAleenan can take the role.[63] According to CNN, McAleenan is "a career official who served in the Obama administration and whom a senior DHS official says is "not an ideologue or fire breather" on immigration."[64] | ||

| 2019 | June 10 | Leadership change | USCIS | Ken Cuccinelli succeeds Lee Cissna as USCIS Director. A Republican politician and lawyer, Cuccinelli had taken hardline positions on immigration-related matters in past jobs. In April 2019, while reporting on the resignation of DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nilsen, Politico had reported that Stephen Miller had been pressuring Trump to get rid of Cissna.[65] Coverage in the New York Times of the public charge rule released by USCIS in August 2019 suggests that this replacement helped the Trump administration move forward faster with the public charge rule than they would have been able to with Cissna.[66] | ||

| 2019 | August 12 (announcement), October 15 (effective date) | USCIS | USCIS announces a new rule restricting lawful permanent residence: any person who has received public benefits such as Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicaid, and public housing assistance for more than a total of twelve months within any 36-month period may be classified as a "public charge" ineligible for permanent residency. Refugees, asylum seekers, pregnant women, children, and family members of those serving in the Armed Forces are excluded from the restrictions.[66][67] | |||

| 2019 | December 20 | Legislation | USCIS | The Liberian Refugee Immigration Fairness (LRIF) provision becomes law as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. This provides an opportunity for certain Liberian nationals and their spouses, unmarried children under 21 years old, and unmarried sons and daughters 21 years old or older living in the United States who meet the eligibility requirements to obtain lawful permanent resident status (receive Green Cards).[68] | Liberia | |

| 2020 | March 1 | Leadership change | USCIS | US District Court Judge Randolph D. Moss rules that Cuccinelli was not appointed to serve as acting director lawfully (i.e., his appointment violated the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998) and therefore lacked authority to issue two directives for which a lawsuit has been filed against him. Cuccinelli is replaced by acting director Mark Koumans. | ||

| 2020 | June 22 | Executive order | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs | H-1B, H-2B, H-4 corresponding to H-1B or H-2B, J, L | In light of increased unemployment levels following the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, United States President Donald Trump issues a presidential proclamation suspending the issuance of new visas in many categories, including H-1B, by United States consulates, till the end of 2020. Existing visas would continue to be honored, and H-1B adjudications by USCIS would continue. The effective impact is that only people already in the United States would be able to transition to or extend H-1B status, and would not be able to travel outside the United States unless they already have a valid visa.[69][70] | |

| 2021 | January 20 | Leadership change | Executive branch | Democratic politician and former vice-president Joe Biden becomes President of the United States after defeating incument Donald Trump in an election and overcoming several legal challenges from Trump disputing the election results. | ||

| 2021 | January 20 | Proclamation | U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Consular Affairs, CBP Office of Field Operations | Newly elected President Joe Biden issues a presidential proclamation revoking Trump's Executive Order 13780 and other related proclamations that prevented individuals from several countries (initially some Muslim-majority countries and later African countries) from entering the United States.[71][72][73] | ||

| 2021 | January 20 | Legislation (proposal) | Executive branch | On its first day in office, Joe Biden's administration proposes a legislative bill called the US Citizenship Act of 2021, that "proposes to roll back many of the executive actions made by President Donald Trump, while providing a legislative path to citizenship for as many as 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States."[72] |

See also

- Timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States

- Timeline of Chinese immigration to the United States

- Timeline of migration-related nongovernmental organizations in the United States

- Timeline of H-1B

- Timeline of student visa policy in the United States

References

- ↑ "Emigrate to the United States". Google Trends. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ "Visa for Canada, USA, United States and America". Google Trends. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Emigrate to the United States". books.google.com. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ "Visa policy and immigrant processing". books.google.com. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ "An act in amendment to the various acts relative to immigration and the imortation of aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor" (PDF). March 3, 1891. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Summary of Immigration Laws, 1875-1918". Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ Hester, Torrie. "Immigration Act of 1891". Immigration to the United States. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Legal History of Immigration". FamilySearch. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 "Organizational Timeline". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ↑ "Dillingham Commission (1907–1910)". Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Brief of Amicus Curiae Law Professors in Support of Respondent (Kerry v. Din)" (PDF). American Bar Association.

- ↑ "Public Law 414: Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952" (PDF). June 27, 1952. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Mutual Education and Cultural Exchange Program" (PDF). Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Public Law 91-225" (PDF). Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "A Legislative History of H-1B and Other Immigrant Work Visas". Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Implementation of L-1 Visa Regulations" (PDF). Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General. August 9, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "H.R.14535 - An Act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act, and for other purposes". Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ Nelson, Gene. "Career Destruction Sites Is What U.S. Colleges Have Become". The Social Contract Press. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "H-1B TEMPORARY PROFESSIONAL WORKER VISA PROGRAM AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY WORKFORCE ISSUES". August 5, 1999. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "H.R.4327 - Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1981". United States Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ↑ "Federal Register: 48 Fed. Reg. 14561 (Apr. 5, 1983)" (PDF). April 5, 1983. pp. 14575–14594. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Alan C. Nelson: Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization Service, February 22, 1982 - June 16, 1989". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. February 4, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ↑ "About the Office". Executive Office for Immigration Review. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ↑ Leslie Maitland Wiener (February 24, 1985). "SENATE APPROVES MEESE TO BECOME ATTORNEY GENERAL". New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ↑ Jackson, Robert L.; John J. Goldman (1989-08-09). "Wallach Found Guilty of Racketeering, Fraud: Meese's Friend, Two Others Convicted in Wedtech Scandal". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Public Law 99-603" (PDF). United States Government Publishing Office. November 6, 1986. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ↑ Bigo, Didier. Foreigners, Refugees Or Minorities?: Rethinking People in the Context of Border Controls and Visas.

- ↑ "Reagan-Bush Family Fairness: A Chronological History". American Immigration Council. December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Aggravated Felonies: An Overview" (PDF). American Immigration Council. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Aggravated Felonies and Deportation". TRAC Immigration. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ Berke, Richard (March 14, 1989). "WASHINGTON TALK: IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION; Service's Chief Tilts Against an 'Oblique' Attack on His Policies". New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "INS Chief Resigns; Under Fire in Justice Dept. Audit". Associated Press. June 26, 1989. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Interpreter releases: report and analysis of immigration and nationality law" (PDF). February 5, 1990. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ Howe, Marvine (March 5, 1990). "New Policy Aids Families of Aliens". New York Times.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Leiden, Warren. "Highlights of the U.S. Immigration Act of 1990". Fordham International Law Journal. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ Stone, Stephanie. "1190 Immigration and Nationality Act". U.S. Immigration Legislation Online. U.S. Immigration Legislation Online. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ Bier, David (June 16, 2020). "The Facts About H-4 Visas for Spouses of H-1B Workers". Cato Institute. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Johnson, Kit (May 13, 2011). "The Wonderful World of Disney Visas". Florida Law Review. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ Leslie Berestein Rojas (May 26, 2011). "It's a Small World: The story of the 'Disney visa'". Southern California Public Radio. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Doris Meissner. Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization Service, October 18, 1993 - November 18, 2000". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ↑ Ifill, Gwen (June 19, 1993). "President Chooses an Expert To Halt Smuggling of Aliens". New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of National Visa Center". National Visa Center. July 26, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers on HRIFA". American Immigration Lawyers Associoation. May 13, 1999. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Green Card Through the Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ↑ "What Was the 2000 Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act?". ProCon.org. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Legal Immigration Family Equity Act" (PDF). United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. December 21, 2000. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ↑ "America's borders: from our consulates to our ports of entry: balancing our security and economic needs". American Immigration Lawyers Association. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ↑ "Beginning January 10, 2011, the U.S. Embassy and Consulates will process visas differently" (PDF). Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Definition of Form I-94 To Include Electronic Format". Federal Register. March 27, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Updates On DHS Plans To Automate Form I-94 Process". August 12, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ "End of Paper I-94 / New I-94 Automation Guidelines". University of Chicago. April 30, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ "DHS Announces Further Travel Restrictions for the Visa Waiver Program - Homeland Security". 2016-02-18.

- ↑ Lind, Dara (January 27, 2017). "Trump's executive order on refugees closes America to those who need it most. It lays the groundwork for a fundamental shift in how the US allows people to enter the country". Vox. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Yanofsky, David (January 27, 2017). "Trump just made it harder for tourists to visit the US". Quartz. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Diamond, Jeremy (January 29, 2017). "Trump's latest executive order: Banning people from 7 countries and more". CNN. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Cairny, Jordain (October 5, 2017). "Senate votes to confirm key Trump immigration official". The Hill. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ↑ Hesson, Ted (September 20, 2018). "The Man Behind Trump's 'Invisible Wall'". Politico. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Kirstjen M. Nielsen Sworn-in as the Sixth Homeland Security Secretary". Department of Homeland Security. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Nixon, Ron (December 5, 2017). "Kirstjen Nielsen, White House Aide, Is Confirmed as Homeland Security Secretary". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ 60.0 60.1 Alvarez, Priscilla; Sands, Geneva (April 8, 2019). "How border hardliners nudged out Nielsen". CNN. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ↑ "Migrant Protection Protocols". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. January 24, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ↑ "DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen resigns after clashes with Trump on immigration". CBS News. April 7, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ↑ Gerstein, Josh; Beasley, Stephanie. "Legality of Trump move to replace Nielsen questioned". POLITICO. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- ↑ Sullivan, Kate; Sands, Geneva; Acosta, Jim (April 8, 2019). "Incoming acting secretary of Homeland Security 'not an ideologue or fire breather'". Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ↑ Kumar, Anita (April 7, 2019). "Stephen Miller pressuring Trump officials amid immigration shakeups". Politico.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Shear, Michael D.; Sullivan, Eileen (August 12, 2019). "Trump Policy Favors Wealthier Immigrants for Green Cards". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ↑ "New Trump rule would target legal immigrants who get public assistance". Reuters. August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Liberian Refugee Immigration Fairness". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ Trump, Donald (June 22, 2020). "Proclamation Suspending Entry of Aliens Who Present a Risk to the U.S. Labor Market Following the Coronavirus Outbreak". White House. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Narea, Nicola (June 22, 2020). "A new Trump proclamation will block foreign workers. It could affect hundreds of thousands of foreigners stranded abroad". Vox. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Biden, Joe (January 20, 2021). "Proclamation on Ending Discriminatory Bans on Entry to The United States". The White House. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "Joe Biden reverses anti-immigrant Trump policies hours after swearing-in. Executive orders will end travel ban and expand census as new president seeks path to citizenship for undocumented migrants". The Guardian. January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ↑ Vance, Tara L. (January 26, 2021). "Immigration Under Biden Administration: Changes in the First 100 Days". Retrieved January 31, 2021.