Timeline of animal testing

This is a timeline of animal testing, attempting to describe the use of non-human animals for scientific research and emergence of policies regulating testing. Most Nobel Prizes in Medicine have involved some form of animal research.[1]

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| Ancient history | Animals testing is early documented in the history of biomedical research. Aristotle and Erasistratus already perform experiments on living animals. Greek physician Galen also conducts experiments on animals to advance the understanding of anatomy, physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Arab physician Ibn Zuhr introduces animal testing as an experimental method for testing surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.[2] |

| 17th century | Debates on the ethics of animal testing are already conducted in the seventeenth century.[2] Throughout the Age of Enlightenment, physiological experiments on animals are carried out for the purpose of scientific progress. However, the moral acceptability of inducing suffering in animals in the name of scientific advancement also becomes an issue raised in opposition of vivisection before the end of the century.[3] |

| 18th century | The century marks the rise of moral consideration for animals. Scientists like Stephen Hales and Albrecht Von Haller are known to be concerned about the moral justification of experimenting on animals.[3] |

| 19th century | By the beginning of the century, the topic of discussion is not if animals can feel or not and to what extent, but rather, whether vivisection is justifiable based on the benefit for humans derived from it. While the second half of the nineteenth century marks the beginning of scientifically meaningful and medically relevant animal research, this period also sees opposition to vivisection becoming widespread in England.[3] |

| 20th century | Before 1900, animal models were mainly used to study the pathophysiology of infections.[4] Drug testing using animals becomes important in the twentieth century.[2] The 1950s marks the beginning of a new concern for animals on the part of scientists and the public.[5] |

| 21st century | Recently, the practice of using animals for biomedical research has come under severe criticism by animal protection and animal rights groups, with several countries passing laws to make the practice more ‘humane’.[2] However it has been estimated that 100 million vertebrates are experimented on around the world every year,[6] with 10–11 million of them in the European Union.[7] |

Numerical and visual data

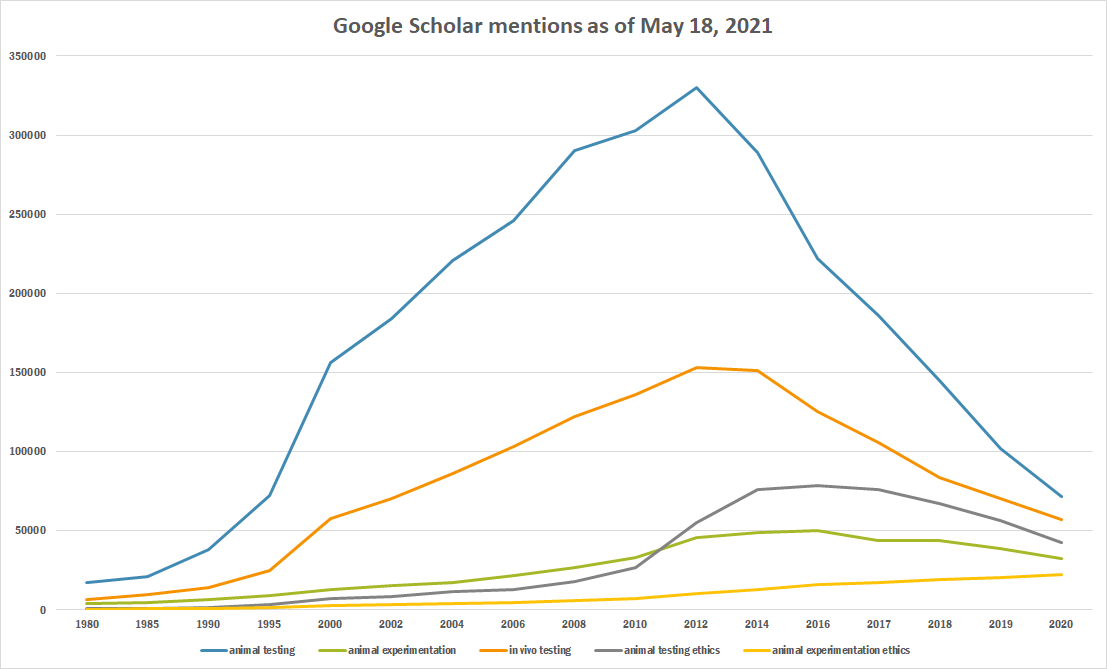

Mentions on Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 18, 2021.

| Year | animal testing | animal experimentation | in vivo testing | animal testing ethics | animal experimentation ethics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 16,900 | 4,100 | 6,660 | 557 | 349 |

| 1985 | 21,000 | 4,500 | 9,760 | 748 | 522 |

| 1990 | 37,800 | 6,220 | 13,800 | 1,330 | 839 |

| 1995 | 72,400 | 8,820 | 24,900 | 3,200 | 1,340 |

| 2000 | 156,000 | 12,600 | 57,500 | 7,080 | 2,680 |

| 2002 | 184,000 | 15,100 | 70,000 | 8,580 | 3,310 |

| 2004 | 221,000 | 17,300 | 86,100 | 11,700 | 3,930 |

| 2006 | 246,000 | 21,500 | 103,000 | 12,800 | 4,740 |

| 2008 | 290,000 | 26,700 | 122,000 | 18,100 | 5,710 |

| 2010 | 303,000 | 33,300 | 136,000 | 26,900 | 7,310 |

| 2012 | 330,000 | 45,500 | 153,000 | 55,200 | 10,300 |

| 2014 | 289,000 | 48,800 | 151,000 | 76,300 | 12,700 |

| 2016 | 222,000 | 49,800 | 125,000 | 78,300 | 15,700 |

| 2017 | 186,000 | 43,700 | 106,000 | 76,000 | 17,300 |

| 2018 | 145,000 | 43,700 | 83,400 | 66,900 | 19,000 |

| 2019 | 102,000 | 39,000 | 70,600 | 56,700 | 20,300 |

| 2020 | 71,300 | 32,200 | 57,000 | 42,300 | 22,400 |

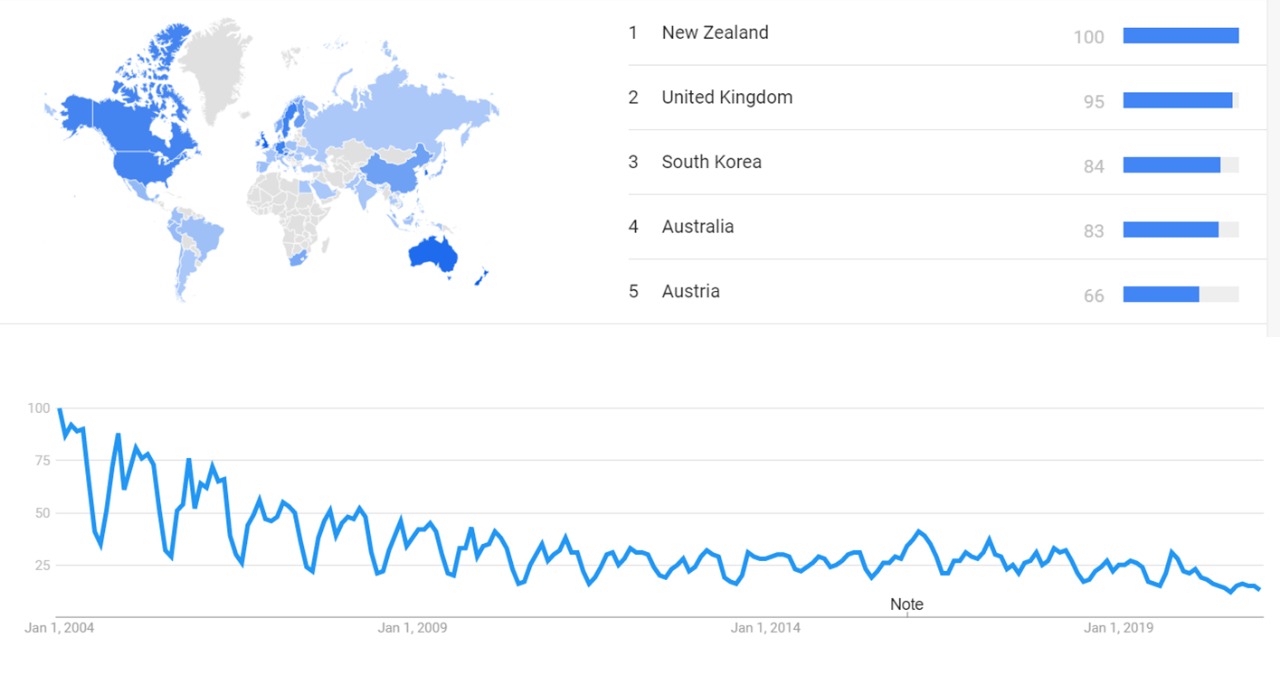

Google trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Animal testing (topic), from January 2004 to January 2021, when the screenshot was taken.[8]

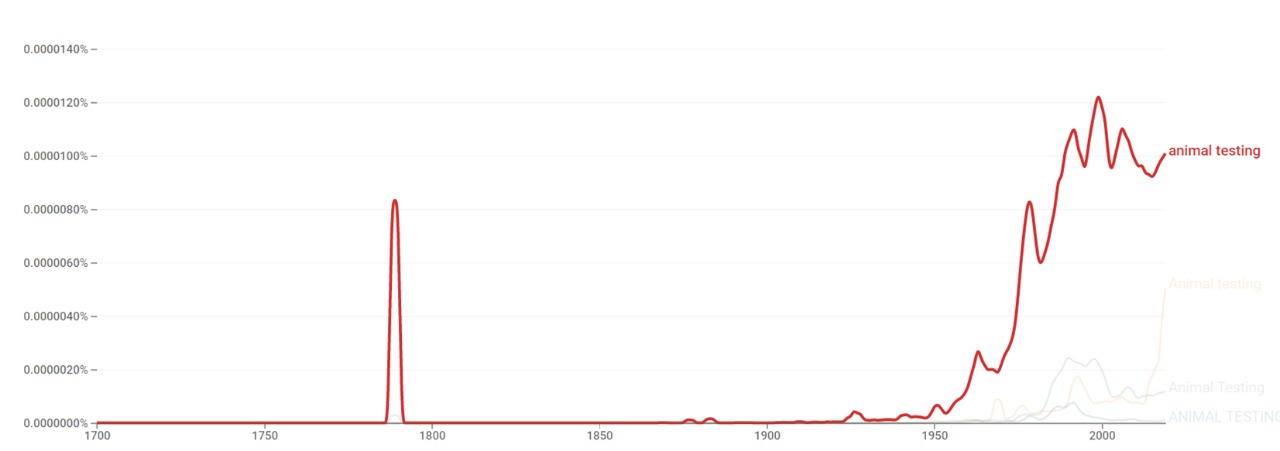

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for animal testing, from 1700 to 2019.[9]

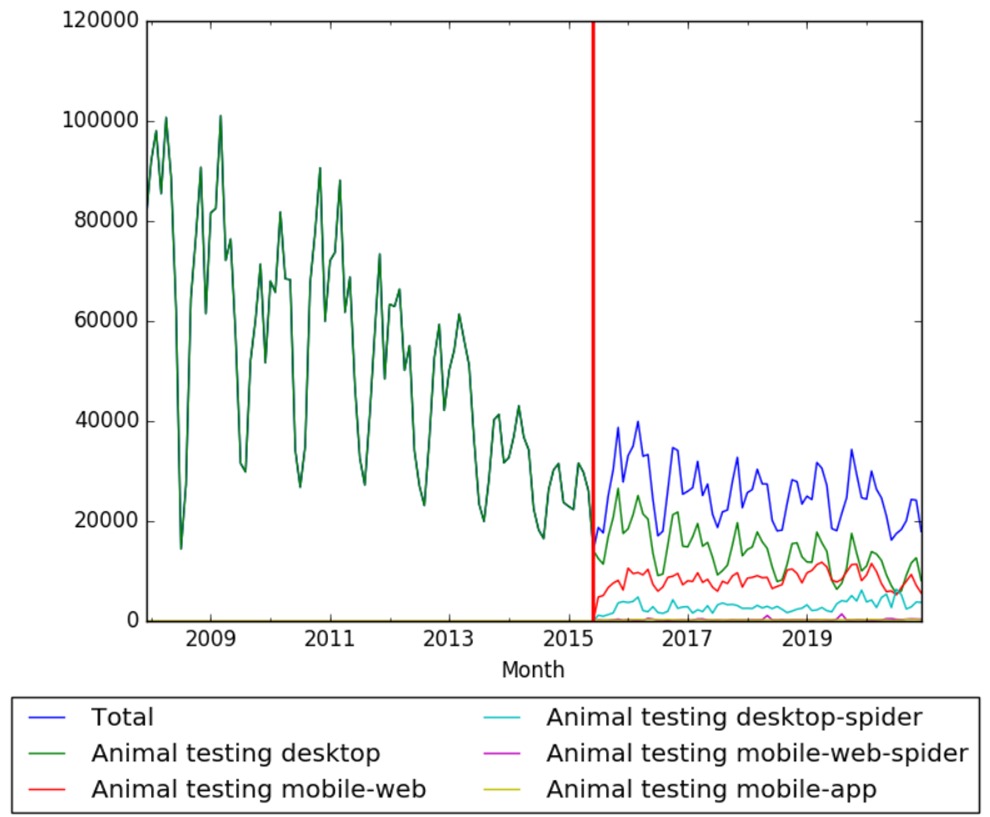

Wikipedia views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article animal testing on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from June 2015; to December 2020.[10]

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | Scientific development | Writings of ancient civilizations all document the use of animal testing. These civilizations, led by men like Aristotle and Erasistratus, use live animals to test various medical procedures.[11] | |

| 1242 | Scientific development | Using animals to study blood circulation, Syrian Arab physician Ibn al-Nafis manages to theorize about the human blood circulatory system. His theories are eventually proven hundreds of years later by William Harvey.[11] | |

| 1596–1650 | Scientific development | French philosopher René Descartes performs vivisections on animals under his belief that animals are ‘machine-like’, interpreted as a belief that animals can not feel pain.[3] | France |

| 1660 | Animal testing (basic biology) | Anglo-Irish scientist Robert Boyle theorizes that living beings need air to live – something unknown at the time. Using animals, Boyle tests and proves his theories.[11] | United Kingdom |

| 1700s | Animal testing (basic biology) | Scientists like Stephen Hales and Luigi Galvani use animals to prove their scientific theories. Some of the theories proved during the 1700s include animation caused by electricity, respiration as combustion, and blood pressure theories.[11] | |

| 1724–1804 | Ethical Development | German philosopher Immanuel Kant acknowledges the sentience of non-human species.[3] | |

| 1783 | Animal testing (travel) | A sheep, duck and rooster are sent up in the newly invented hot-air balloon. The balloon flies for 3.2 kilometers and lands safely.[12] | |

| 1783–1855 | Animal testing (basic biology) | French physiologist François Magendie lives. Magendie is considered among the most infamous of his time for the types of experiments he conducts and the cruelty they entail. A notorious vivisector, Magendie would shock even many of his contemporaries with the live dissections performed by him at public lectures in physiology.[3] | France |

| 1840s | Animal testing | Animal experimentation becomes routine after the discovery of anesthetic allows for experiments on animals to continue with less guilt due to less pain inducement.[3] | |

| 1866 | Organization | Philantropist Henry Bergh founds the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), which would press unsuccessfully for laws to abolish experiments involving animals in the 1860s and 1870s.[13] | United States |

| 1875 | Organization | The Victoria Street Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection is founded. It is the first society for animal protection. | |

| 1876 | Legal | Great Britain passes the Cruelty to Animals Act.[11] However, the Act's implementation permits "a great amount of pain and suffering to animals", and the adequacy of anaesthetics is questionable.[14] | United Kingdom |

| 1880 | Animal testing (medical cures) | French biologist Louis Pasteur uses sheep and anthrax to prove the theory that germs are harmful and what causes illness. He eventually develops the practice of pasteurization, which consists in boiling the milk to kill bacteria and germs.[11] | France |

| 1883 | Organization | American philanthropist Caroline Earle White establishes the American Anti-Vivisection Society.[13] | United States |

| 1890s | Animal testing (basic biology) | Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov uses dogs to describe classical conditioning.[15] | Russia |

| 1901 | Animal testing (medical cures) | German physiologist Emil von Behring uses guinea pigs to test his theories on diphtheria, and later uses the findings to create an immunization for humans. Von Behring would be awarded the Nobel Prize for his advancement of medicine.[11] | Germany |

| 1920 | Animal testing (basic biology) | English electrophysiologist Edgar Adrian experiments on a frog to prove the way the brain sends signals for communication. Adrian is later awarded the Nobel Prize for his findings.[11] | |

| 1921 | Animal testing (medical cures) | Canadian scientist Frederick Banting uses dogs, and later cows, to experiment with the pancreas and insulin to develop a treatment for diabetes.[11] | |

| 1938 | Policy | The United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act requires safety testing of drugs on animals before they can be marketed.[2][16] | United States |

| 1940s | Animal testing (medical cures) | By experimenting on guinea pigs, Corwin Hinshaw finds that antibodies found in the soil could help cure tuberculosis.[11] | |

| 1940s | Animal testing (medical cures) | American medical researcher Jonas Salk uses monkeys to isolate and vaccinate against the polio virus.[11] | |

| 1949 | Animal testing (travel) | Albert II becomes the first monkey in space on June 4, 1949. He reaches an altitude of 83 miles (134 km), but dies on impact when the parachute fails.[12] | |

| 1949 | Alternative testing | The first computer operated mannequin is built by Alderson Research Labs (ARL) Sierra Engineering. These devices would replace live animal trauma testing for automobile crash testing. Prior to this, live pigs were used as test subjects for crash testing.[17][18] | United States |

| 1950s | Animal testing (medical cures) | Scientists use rodents, dogs, cats, monkeys, and rabbits to test the use of anesthesia.[11] In the 1950s, the Soviet Union launches a total of 12 dogs on various suborbital flights. Stray dogs are used since they are thought to be capable of handling extreme cold.[12] | |

| 1951 | Organization | The Animal Welfare Institute is founded.[5] | |

| 1957 (November 3) | Animal testing (travel) | Laika becomes the first animal sent into orbit.[19] | Russia |

| 1959 | Ethical Development | William Russell and Rex Burch publish The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique.[5] | |

| 1959 | Alternative testing | The Three Rs (3Rs) are first described by W. M. S. Russell and R. L. Burch as guiding principles for more ethical use of animals in testing.[20] The 3Rs are:

|

|

| 1960 | Animal testing (medical cures) | American cardiovascular surgeon Albert Starr pioneers heart valve replacement surgery in humans after a series of surgical advances in dogs.[21] | United States |

| 1963 | Animal testing (travel) | France launches the first cat into space. Félicette reaches an altitude of 160 km and lands safely.[12] | France |

| 1963 | Animal testing (basic biology) | South African biologist Sydney Brenner proposes research into nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, primarily in the area of neuronal development.[22] | |

| 1964–1966 | Animal testing (travel) | China launches mice, rats and dogs into space.[12] | China |

| 1966 | Policy | The United States Congress passes the Animal Welfare Act, a federal law regulating animal use in the United States.[5] | United States |

| 1968 | Animal testing (medical cures) | Medics and scientists use dogs to attempt the replacing of a heart valve. Other studies using animals today include the studying of AIDS and leprosy.[11] | |

| 1968 | Animal testing (travel) | First animals are sent in deep space and to circle the Moon. The Soviet Zond 5 becomes the first spacecraft to circle the satellite, carrying a payload of two Russian tortoises, wine flies, mealworms, plants, seeds and bacteria.[12] | |

| 1969 | Alternative testing | The Fund for the Replacement of Animals in Medical Experiments is formed with the purpose to relieve the suffering of animals used as subjects in biomedical research, and to promote and support research into acceptable new techniques as substitutes for the use of animals in all such research.[23] | United Kingdom |

| 1970s | Animal testing (medical cures) | Australian psychiatrist John Cade uses lithium salts in guinea pigs in his investigation to find a treatment for depression and other manic conditions.[11] | |

| 1974 | Animal testing (basic biology) | German biologist Rudolf Jaenisch manages to produce the first transgenic mammal, by integrating DNA from the SV40 virus into the genome of mice.[24] | |

| 1975 | Ethical Development | Australian philosopher Peter Singer publishes Animal Liberation, arguing that the interests of animals should be considered because of their ability to feel suffering and that the idea of rights was not necessary to weigh against the relative worth of animal experimentation. | |

| 1980 (approximate) | Activism | The movement against animal testing in North America begins.[3] | North America |

| 1981 | Alternative testing | The John's Hopkins' Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing is founded. It is the leading alternatives center in the United States.[25] | United States |

| 1986 | Statistics | The United States Congress Office of Technology Assessment reports that estimates of the animals used in the United States range from 10 million to upwards of 100 million each year, and that their own best estimate is at least 17 million to 22 million.[26] | United States |

| 1986 | Policy | The Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS123) is established by the European Union[27], with the purpose to reduce the number of animals used in research and encouraging signing parties to use animals only where alternatives do not exist. The document establishes general principles for when and how experiments with animals are to be carried out and also provides technical details on how to house animals.[28] | European Union |

| 1986 | Policy | The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 is passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It regulates the use of protected animals in any experimental or other scientific procedure which may cause pain, suffering, distress or lasting harm to the animal.[29] | United Kingdom |

| 1989 | Alternative testing | The ZEBET (Zentrealstelle ErfassungBewertung von zur Ersatz und zum Erganzungsmethoden Tierversuch - National Center for the Documentation and Evaluation of Alternatives for Methods of Animal Experimentation) is created in Germany.[30] | Germany |

| 1991 | Organization | The European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods is established to develop alternatives to animal testing.[31] | |

| 1991 | Animal testing (transportation) | The New York Times publishes an article titled 19,000 Animals Killed in Automotive Crash Tests which reports that about 19,000 dogs, rabbits, pigs, ferrets, rats and mice have been killed during the last decade in automobile safety tests performed by General Motors. The testing would be condemned by leading animal rights organization, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, calling for a boycott of General Motors products.[17] | United States |

| 1992 | Statistics | Researchers at Tufts University Center for Animals and Public Policy estimate that 14–21 million animals were used in U.S. laboratories in 1992, a reduction from a high of 50 million used in 1970.[32] | United States |

| 1993 | Alternative testing | General Motors discontinues their live testing. Other manufacturers follow suit shortly thereafter.[17] | |

| 1994 | Alternative testing | The Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM) is established. It facilitates international collaboration on the development of alternative test methods.[33] | United States |

| 1996 | Animal testing (basic biology) | Dolly the sheep becomes the first cloned animal, coming from an adult sheep cell. Science continues using animals for research, in spite of protests.[3][11] | United Kingdom |

| 1996 | Activism | The Coalition for Consumer Information on Cosmetics is formed by animal protection groups. It manages the Leaping Bunny cruelty-free certification program in the United States and Canada.[31] | North America |

| 1997 | Animal testing (medical cures) | Innovations in frogs, Xenopus laevis by developmental biologist Jonathan Slack of the University of Bath, create headless tadpoles, which could allow future applications in donor organ transplantation.[34] | United Kingdom |

| 1997 | Alternative testing | The ICCVAM (Interagency Coordinating Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods) is formed by government agencies in the United States. It consists of 15 research and regulatory agencies, among which number the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR).[30] | United States |

| 1998 | Policy | Animal testing for cosmetic products and ingredients is banned in the United Kingdom.[31] | United Kingdom |

| 2000 | Policy | The Interagency Coordination Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM) Authorization Act is signed in the United States. The law establishes a coordinated effort by U.S. agencies to evaluate and adopt alternative test methods.[31] | United States |

| 2001 | Statistics | The number of mice and rats used in the United States alone in 2001 is estimated at 80 million.[35] | United States |

| 2001 | Statistics | China exports over 12,000 macaques for research in 2001 (4,500 to the United States), all from self-sustaining purpose-bred colonies.[36] The second largest source is Mauritius, from which 3,440 purpose-bred cynomolgous macaques were exported to the United States in 2001.[37] | China, Mauritius |

| 2004 | Policy | A law phasing out the production and sale of animal tested cosmetics is passed by the European Union.[31] | European Union |

| 2004 | Alternative testing | The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) approves non-animal alternative tests for dermal absorption, dermal corrosivity, and dermal phototoxicity.[31] | |

| 2004 | Alternative testing | The British National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs) is established.[38] | United Kingdom |

| 2005 | Alternative testing | The European Partnership for Alternative Approaches to Animal Testing is created.[39] | |

| 2005 | Alternative testing | The Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods (JaCVAM) is established.[31] | Japan |

| 2007 | Statistics | As of date, the United States and Gabon are the only countries that still use chimpanzees for research purposes.[40][41] | United States, Gabon |

| 2007 | Alternative testing | FRANCOPA is created in France as a platform dedicated to development, validation, and dissemination of alternative methods in animal testing.[42] | France |

| 2007 | Alternative testing | Norecopa is founded in Norway as a consensus platform for the replacement, reduction and refinement of animal experiments.[43] | Norway |

| 2008 | Animal testing (explosives) | The United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency uses live pigs to study the effects of improvised explosive device explosions on internal organs, especially the brain.[44] | United States |

| 2008 | Alternative testing | The Finish Center for Alternative Methods (FICAM) is established.[45] | Finland |

| 2009 | Alternative testing | The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development approves non-animal alternative tests for ocular toxicity.[31] | |

| 2010 | Alternative testing | The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development approves a non-animal alternative test for dermal irritation.[31] | |

| 2010 | Policy | A law phasing out the sale of animal tested cosmetics is passed in Israel.[31] | Israel |

| 2010 | Policy | The EU Directive 2010/63/EU is adopted by the European Union with the purpose of setting more stringent ethical and welfare standards. This legal framework includes the requirement for methods allowing for the replacement of the use of animals when possible, the reduction of the number of animals used, and the refinement of experimental methods involving animals. The Directive itself is based on the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS123) established in 1986.[27] | European Union |

| 2011 | Statistics | The United States has the largest colony in the world of more than 1,000 chimpanzees at six laboratories.[46] | |

| 2011 | Alternative testing | The Brazilian Center for the Validation of Alternatives Methods is established.[30] | Brazil |

| 2011 (December 15) | The United States National Academy of Medicine committee concludes in their Chimpanzees in Biomedical and Behavioral Research: Assessing the Necessity report that “while the chimpanzee has been a valuable animal model in past research, most current use of chimpanzees for biomedical research is unnecessary".[47] | United States | |

| 2013 | Policy | Ban on the sale of all cosmetics that have been newly tested on animals is implemented in Israel.[31] | Israel |

| 2013 | Policy | Ban on cosmetic animal testing and the sale of newly animal tested cosmetics is implemented in Norway.[31] | Norway |

| 2013 | Policy | A revised legislation of the British Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 comes into force. repealing the EU Directive 86/609/EEC, and replacing it for the EU Directive 2010/63/EU.[48][49] | United Kingdom |

| 2014 | Policy | The Humane Cosmetics Act (HCA) legislation is introduced in the United States, to prohibit cosmetic animal testing and the sale of newly animal tested cosmetics.[31] | United States |

| 2014 | Policy | India bans cosmetic animal testing.[31] | India |

| 2014 | Policy | A rule to remove mandatory animal testing for non-special use cosmetics manufactured within China is implemented by the government.[31] | China |

| 2015 (December) | Policy | Canada reintroduces the Cruelty-Free Cosmetics Act.[31] | Canada |

| 2015 | Alternative testing | The Romanian Center for Alternative Test Methods (ROCAM) is established to promote the application of alternative methods in industry and their acceptance by regulators in Romania and also the development of new methods and approaches.[50] | Romania |

| 2015 | Statistics | An article published in the Journal of Medical Ethics argues that the use of animals in the United States dramatically increased in recent years. Researchers find this increase is largely the result of an increased reliance on genetically modified mice in animal studies.[51] | United States |

| 2016 (June) | Policy | Ban of production and sale of animal-tested cosmetics is announced in Australia.[31] | Australia |

| 2016 (October) | Policy | Cosmetic animal testing for finished products and ingredients is banned in Taiwan.[31] | Taiwan |

| 2016 (December) | Policy | An ordinance to ban the sale of newly animal tested cosmetics is passed in Switzerland.[31] | Switzerland |

| 2016 | Statistics | The United States Department of Agriculture lists testing animals that include 60,979 dogs, 18,898 cats, 71,188 non-human primates, 183,237 guinea pigs, 102,633 hamsters, 139,391 rabbits, 83,059 farm animals, and 161,467 other mammals, a total of 820,812, a figure that includes all mammals except purpose-bred mice and rats.[52] | United States |

| 2016 | Statistics | A total of 18,898 cats – which are most commonly used in neurological research – were used in the United States in the year,[52] around a third of which were used in experiments which have the potential to cause "pain and/or distress".[53] | United States |

| 2017 (February) | Policy | Guatemala becomes first country in the Americas to ban cosmetic animal testing.[31] | Guatemala |

| 2017 (June) | Policy | The Humane Cosmetics Act is reintroduced in the United States.[31] | United States |

| 2017 (October) | Alternative testing | New alternative test methods for ocular toxicity and skin allergy are approved by OECD.[31] | |

| 2017 (December) | Policy | Legislation banning sale of animal-tested cosmetics is introduced in South Africa.[31] | South Africa |

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

- Timeline of animal welfare and rights

- Timeline of animal welfare and rights in Europe

- Timeline of animal welfare and rights in the United States

- Timeline of Animal Equality

External links

References

- ↑ Coyne, Mark S.; Allin, Craig Willard; Adams, McCrea. Natural Resources: Abrasives; general mining law of 1872.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Hajar, Rachel. "Animal Testing and Medicine". doi:10.4103/1995-705X.81548. PMC 3123518. PMID 21731811. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "Medical Testing on Animals: A Brief History". animaljustice.ca. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Animal Testing in Infectiology (Axel Schmidt, Olaf F. Weber ed.).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Hayhurst, Chris. Animal Testing: The Animal Rights Debate.

- ↑ Taylor, Katy; Gordon, Nicky; Langley, Gill; Higgins, Wendy (2008). "Estimates for worldwide laboratory animal use in 2005". ATLA. 36 (3). FRAME: 327–42. PMID 18662096.

- ↑ Hunter, Robert G. (1 January 2014). "Alternatives to animal testing drive market". Gen. Eng. Biotechnol. News. Vol. 34, no. 1. p. 11.

While growth has leveled off and there have been significant reductions in some countries, the number of animals used in research globally still totals almost 100 million a year.

- ↑ "Animal testing". trends.google.com. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "Animal testing". books.google.com. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ "Wikipedia Views: results". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 "History of Animal Testing". softschools.com. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Cosmic Menagerie: A History of Animals in Space (Infographic)". space.com. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rothenberg, Marc. History of Science in United States: An Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Lyons, Dan. The Politics of Animal Experimentation.

- ↑ Windholz G (1987). "Pavlov as a psychologist. A reappraisal". Pavlov. J. Biol. Sci. 22 (3): 103–12. PMID 3309839.

- ↑ Gad, Shayne C. Animal Models in Toxicology.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "A Brief History of the Original Automotive Crash Dummy; Meet Sierra Sam". keepingussafe.org. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ↑ "History of Crash Test Dummies". humaneticsatd.com. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ↑ The Handy Science Answer Book.

- ↑ Russell, W.M.S. and Burch, R.L., (1959). The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique, Methuen, London. Template:ISBN [1]

- ↑ "Portland surgeon receives top medical prize". The Oregonian. 15 September 2007.

- ↑ Brenner S (May 1974). "The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans". Genetics. 77 (1): 71–94. PMC 1213120. PMID 4366476.

- ↑ Balls, Michael; Fentem, Julia H. "The Fund for the Replacement of Animals in Medical Experiments (FRAME): 23 Years of Campaigning for the Three Rs". onlinelibrary.wiley.com. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Jaenisch R, Mintz B (1974). "Simian Virus 40 DNA Sequences in DNA of Healthy Adult Mice Derived from Preimplantation Blastocysts Injected with Viral DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1250–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250. PMC 388203. PMID 4364530.

- ↑ "Philanthropy at the Johns Hopkins Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing". caat.jhsph.edu. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing and Education, U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment, Washington, D.C.:Government Printing Office, 1986, p. 64. In 1966, the Laboratory Animal Breeders Association estimated in testimony before Congress that the number of mice, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits used in 1965 was around 60 million. (Hearings before the Subcommittee on Livestock and Feed Grains, Committee on Agriculture, U.S. House of Representatives, 1966, p. 63.)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "EuroScience supports Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes". euroscience.org. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Olsson, Anna S; Pinto da Silva, Sandra; Townend, David; Sandøe, Peter. "Protecting Animals and Enabling Research in the European Union: An Overview of Development and Implementation of Directive 2010/63/EU". doi:10.1093/ilar/ilw029.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Animal Research at Nottingham". nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "Alternative methods in toxicity testing: the current approach". scielo.br. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ 31.00 31.01 31.02 31.03 31.04 31.05 31.06 31.07 31.08 31.09 31.10 31.11 31.12 31.13 31.14 31.15 31.16 31.17 31.18 31.19 31.20 31.21 31.22 "Timeline: Cosmetics Testing on Animals". humanesociety.org. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Rowan, A., Loew, F., and Weer, J. (1995) "The Animal Research Controversy. Protest, Process and Public Policy: An Analysis of Strategic Issues." Tufts University, North Grafton. cited in Carbone 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ "About ICCVAM". ntp.niehs.nih.gov. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Morton, Oliver; Williams, Nigel (1997). "First Dolly, Now Headless Tadpoles". 278 (5339): 798–798. JSTOR 2894431.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Carbone, p. 26.

- ↑ Council, National Research (29 July 2003). "International Perspectives: The Future of Nonhuman Primate Resources: Proceedings of the Workshop Held April 17-19, 2002". nap.edu. doi:10.17226/10774. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Council, National Research (29 July 2003). "International Perspectives: The Future of Nonhuman Primate Resources: Proceedings of the Workshop Held April 17-19, 2002". nap.edu. doi:10.17226/10774. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Singh, Jatinder. "The national centre for the replacement, refinement, and reduction of animals in research". PMC 3284057. PMID 22368436.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "European Partnership for Alternative Approaches to Animal Testing". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Cohen, Jon (26 January 2007). "The Endangered Lab Chimp". Science. 315 (5811): 450–452. doi:10.1126/science.315.5811.450. PMID 17255486. Retrieved 6 October 2018 – via www.sciencemag.org.

- ↑ "Chimpanzees in research and testing worldwide: Overview, oversight and applicable laws" (PDF). jhsph.edu. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "FRANCOPA". francopa.fr. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ "About Norecopa". norecopa.no. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Brook, Tom Vanden, "Brain Study, Animal Rights Collide", USA Today (7 April 2009), p. 1.

- ↑ "Evolution of FICAM and development of human relevant in-vitro models". upmbiochemicals.com. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ "Release and Restitution for Chimpanzees in U.S. Laboratories: Facilities and Numbers". releasechimps.org. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "Chimpanzees in Biomedical and Behavioral Research: Assessing the Necessity". iom.edu. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ "Animal testing and research". gov.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Romanian Center for Alternative Test Methods (ROCAM)". rocam.usamvcluj.ro. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Goodman, J.; Chandna, A.; Roe, K. (2015). "Trends in animal use at US research facilities". Journal of Medical Ethics. 41 (7): 567–569. doi:10.1136/medethics-2014-102404. PMID 25717142. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "USDA Statistics for Animals Used in Research in the US". Speaking of Research.

- ↑ "Annual Report Animals" (PDF). Aphis.usda.gov. Retrieved 6 October 2018.