Timeline of palliative care

This is a timeline of palliative care, attempting to describe important events in the history of hospices until the formalization of palliative care in the late 20th century.

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 12th century < | Understanding palliative care begins with the developent of hospices. These are used in the Middle Ages in Europe and Mediterranean regions as a place of rest for travellers and pilgrims. Established and run by religious orders, the hospices offer special hospitality and care to travellers who are far from home and to people who are ill or dying. The hospices disappear for a while, but re-emerge in the 19th century in the United Kingdom and France particularly, again run by religious orders, and again caring for people who are terminally ill, but also providing accommodation for the incurable and destitute.[1] |

| 20th century | The development by the second half of the century of new technologies and effective specific treatments for disease still leaves much suffering unaddressed.[2] However, palliative care and hospices develop rapidly since the late 1960s, after their modern introduction in Britain by Cicely Saunders. Palliative care begins to be defined as a subject of activity in the 1970s and comes to be synonymous with the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual support of patients with life-limiting illness, delivered by a multidisciplinary team.[3] The movement develops in the United States and Europe in the late 1970s.[4] The hospice concept is introduced in China in the 1980s.[5] In the late 1980s, several notable palliative caregivers, with the support of like-minded physicians and bioethicists, endorse the moral permissibility of physician-assisted suicide.[6] |

| 21st century | A 2006 study found that some form of hospice or palliative care service is offered in about half of the countries in the world. While it is estimated that there are more than 10,000 international hospice and palliative programs today, it is also estimated that 18 million will still die in unnecessary pain and distress each year.[7] |

Full timeline

| Year | Event type | Details | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1701 | Publication | A British monograph refers to the curative and palliative uses of opium as a "noble panacea".[8] | United Kingdom |

| 1802 | Field development | The term "palliate" already appears in the title of a medical paper in England.[8] | United Kingdom |

| 1842 | Facility | Jeanne Garnier establishes L'Association des Dames du Calvaire in Lyon.[8] | France |

| 1890 | Publication | London surgeon Herbert Snow publishes a text on the palliative treatment of terminal cancer, with an appendix on the use of the opium pipe.[8] | United Kingdom |

| 1935 | Publication | Harvard physician Alfred Worcester publishes three lectures titled The Care of the Aged, the Dying and the Dead, intending to serve as outlines of what medical students should be taught because of the "unpardonable" shifting of care for the dying to nurses and sorrowing relatives.[8] | United States |

| 1950s | Field development | English nurse Cicely Saunders first articulates her ideas about modern hospice care around that time, based on the careful observation of dying patients. Saunders advocated that only an interdisciplinary team could relieve the “total pain” of a dying person in the context of his or her family, and the team concept is still at the core of palliative care.[9] | United Kingdom |

| 1952 | Field development | End-of-life care survey: A report based on the observations of district nurses throughout the United Kingdom of some 7050 cases, published by the Marie Curie Memorial Foundation, reveals appalling conditions of suffering and deprivation among many patients dying of cancer at home.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1960 | Field development | End-of-life care survey: In the United Kingdom, Glyn Hughes conducts a nationwide survey for the Gulbenkian Foundation, including widespread consultations, 300 site visits and contacts with 600 family doctors. Conditions in charitable homes are judged seriously inadequate, with deficiencies in financial support and staffing, and a large proportion of the nursing homes visited are deemed ‘quite unsuited—and in some cases amounting to actual neglect when measured by standards that can reasonably be expected’.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1963 | Field development | End-of-life care survey: John Hinton publishes a unique detailed study of the physical and mental distress of the dying. His observations from the wards of a London teaching hospital show that much suffering remains unrelieved and also how most patients are well aware of their prognosis despite the lack of information normally given at that time.[2] | United Kingdom |

| 1964 | Field development | The concept of ‘total pain’ is defined. It includes not only physical symptoms but also mental distress and social or spiritual problems.[2] | |

| 1967 | Facility | St Christopher's Hospice opens in London, established by Dr Cicely Saunders. It is considered the first modern hospice.[7][1] | United Kingdom |

| 1969 | Publication | Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross publishes On Death and Dying, introducing the further called Kübler-Ross model, (also known as the five stages of grief) which postulates a progression of emotional states experienced by both terminally ill patients after diagnosis and by loved-ones after a death. The five stages are chronologically: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.[9][7] | |

| 1972 | Field development | The first national hearings on the subject of death with dignity are conducted by the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging. In it, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross testifies, stating in her testimony, “We live in a very particular death-denying society. We isolate both the dying and the old, and it serves a purpose. They are reminders of our own mortality. We should not institutionalize people. We can give families more help with home care and visiting nurses, giving the families and the patients the spiritual, emotional, and financial help in order to facilitate the final care at home.”[10] | United States |

| 1974 | Field development | Canadian physician Balfour Mount, a surgical oncologist at The Royal Victoria Hospital of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, coins the term palliative care to avoid the negative connotations of the word hospice in French culture, and introduces Dr. Saunders’ innovations into academic teaching hospitals. Mount is the first to demonstrate what it meant to provide holistic care for people with chronic or life-limiting diseases and their families who were experiencing physical, psychological, social, or spiritual distress.[9][1] | Canada |

| 1974 | Policy | The first hospice legislation is introduced in the United States by Senators Frank Church and Frank E. Moss to provide federal funds for hospice programs. The legislation is not enacted.[11] | United States |

| 1974 | Facility | The Connecticut Hospice is founded in Branford, Connecticut, by American nurse Florence Wald, along with two pediatricians and a chaplain.[10] | United States |

| 1978 | Field development | A United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare task force reports that “the hospice movement as a concept for the care of the terminally ill and their families is a viable concept and one which holds out a means of providing more humane care for Americans dying of terminal illness while possibly reducing costs. As such, it is the proper subject of federal support.”[10] | United States |

| 1979 | Facility | The first hospice in New Zealand opens.[12] | New Zeland |

| 1980 | Facility | A hospice opens in Harare (Salisbury, at the time), Zimbabwe, the first in Sub-Saharan Africa.[13] | Zimbabwe |

| 1981 | Facility | The first hospice in Japan opens.[14] | Japan |

| 1982 | Organization | The United States Congress creates the Medicare Hospice Benefit.[7] | United States |

| 1983 | Facility | The first hospice in Israel opens.[15] | Israel |

| 1986 | Field development | Regarding the fact that effective specific treatments for disease leave much suffering unaddressed, professor Patrick Wall writes, ‘Symptoms were placed on one side and therapy directed at them was denigrated’.[2] | |

| 1986 | Facility | The first hospice in India, Shanti Avedna Ashram, opens in Bombay.[16][17][18] | India |

| 1987 | Organization | The Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa is formed.[19] | South Africa |

| 1987 | Field development | A recognized specialty on palliative care is established in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, following the demonstration of appropriate, scientifically based and patient-centered treatment.[2] | |

| 1987 | Facility | The Beijing Songtang Care Hospital, an early hospice in China, is founded in Beijing.[5] | China |

| 1988 | Facility | The first modern free-standing hospice in China opens in Shanghai.[20] | China |

| 1988 | Facility | The first research center for palliative care in China is established in Tianjin Medical University.[11] | China |

| 1988 | Assisted suicide | According to a General Resolution, "Unitarian Universalists advocate the right to self-determination in dying, and the release from civil or criminal penalties of those who, under proper safeguards, act to honor the right of terminally ill patients to select the time of their own deaths".[21] | |

| 1988 | Organization | The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine is established.[22] | United States |

| 1990 | Facility | The first hospice unit in Taiwan, where the term for hospice translates "peaceful care", is innaugurated.[23] | Taiwan |

| 1990 | WHO establishes one of the first widely used definitions of palliative care: “the active, total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment.”[24] | ||

| 1990 | The United States Supreme Court establishes the right of all American citizens to refuse all forms of treatment (including life-sustaining treatment and artificial hydration and nutrition), to have a constitutional basis in the 14th Amendment liberty rights clause.[25] | United States | |

| 1990 | Facility | Nairobi Hospice opens in Nairobi, Kenya.[19] | Kenya |

| 1991 | Advance healthcare directive | In the United States, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA)[26] comes into effect in December 1991, and requires healthcare providers (primarily hospitals, nursing homes and home health agencies) to give patients information about their rights to make advance directives under state law.[27] | United States |

| 1992 | Facility | The first free-standing hospice in Hong Kong, where the term for hospice translates "well-ending service", opens.[28] | Hong Kong |

| 1993 | Organization | The Pain and Palliative Care Society is established in India. It is the first charitable society for community based palliative care in Low and Middle income countries.[29] | India |

| 1993 | Organization | The Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM) is founded.[30] | Australia, New Zealand |

| 1993 | Policy | Hospice is installed as a guaranteed benefit in the United States.[7] | United States |

| 1993 | Book | The Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine is first published in Great Britain.[6] | United Kingdom |

| 1994 | Organization | The Committee of Rehabilitation and Palliative Care of China Anti-cancer Association (CRPC) is founded.[5] | China |

| 1994 | Journal | The European Journal of Palliative Care is established to provide an information and communication resource for all professionals involved in the provision of palliative care across Europe.[31] | |

| 1995 | Facility | The first Palliative Care Unit in Malaysia is set up.[32] | Malaysia |

| 1996 | Book | N.L. Carolone's Handbook of Palliative Care in Cancer is published in the United States.[6] | United States |

| 1997 | Report | The United States Institute of Medicine report, Approaching Death: improving care at the end of life (M.I. Field and C.K. Cassel, editors) documents glaring deficiencies in end-of-life care in the United States. With the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and George Soros’ Open Society Institute, a major effort to bring palliative care into mainstream medicine and nursing is launched.[9] | United States |

| 1997 | Facility | The first hospice in Russia is established in Moscow.[33][34] | Russia |

| 1997 | Assisted suicide | The Colombian Constitutional Court allows for the euthanasia of sick patients who requested to end their lives, by passing Article 326 of the 1980 Penal Code.[35] | Colombia |

| 1997 | Assisted suicide | A study by Glasgow University's Institute of Law & Ethics in Medicine finds pharmacists (72%) and anaesthetists (56%) to be generally in favor of legalizing PAS. Pharmacists are twice as likely as medical GPs to endorse the view that "if a patient has decided to end their own life then doctors should be allowed in law to assist".[36] | United Kingdom |

| 1998 | Book | Palliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual (edited by N. MacDonald) is published in the United States.[6] | United States |

| 1998 | Journal | The Journal of Palliative Medicine is launched.[6] | |

| 1999 | In an evidence-based review of feeding-tube use in patients with advanced dementia, researchers show no medical benefits of feeding tubes but instead find harms including increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, gastric perfration, and local irritation.[25] | ||

| 1999 | Organization | The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care is formed.[6] | |

| 2002 | Organization | The African Palliative Care Association is established in Capetown.[37] | South Africa |

| 2003 | Organization | Pallium India is established as a national registered charitable trust, aimed at providing quality palliative care and effective pain relief for patients in India.[38] | India |

| 2004 | Publication | Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care are first released, expanding the focus of palliative care to include not just dying patients, but also patients diagnosed with life-limiting illnesses.[9] | United States |

| 2004 | Policy | The Chinese Ministry of Health stipulates that the existence of hospice and palliative care be one of the accreditation standards for general hospitals.[11] | China |

| 2004 | More than 1 million people with a life-limiting illness are served by the hospices in the United States, the first time the million-person mark is crossed.[10] | United States | |

| 2004 | Assisted suicide | Final Exit Network is founded as a nonprofit run by volunteers who believe mentally competent adults have a right to end their lives if they suffer from unbearable pain.[39] | United States |

| 2004 | Program | A national end of life care program is established in the United Kingdom to identify and propagate best practice for end-of-life care in the country.[40] | United Kingdom |

| 2005 | Policy | The State Council of China issues the Regulations on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, to ensure enough opioids for medical use for patients with pain.[5] | China |

| 2005 | Conference | The first national conference on access to hospice and palliative care is hosted by the United States National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in Saint Louis.[10] | United States |

| 2005 | The number of hospice provider organizations throughout the United States tops 4,000 for the first time.[10] | United States | |

| 2005 | Notable death | Cicely Saunders dies at St Christopher's Hospice at the age of 87 years.[41] | United Kingdom |

| 2006 | Program | There are 57 palliative medicine fellowship programs in the United States with approximately 100 trainees.[9] | United States |

| 2006 | Policy | The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recognize the subspecialty of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.[9] | United States |

| 2006 (October 1) | The Inaugural World Day is held to focus global attention on hospice and palliative care. Events are held in 70 countries.[10] | ||

| 2006 | Assisted suicide | Belgium partially legalizes euthanasia with certain regulations: the patient must be an adult and in a "futile medical condition of constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated".[42], the patient must have a long-term history with the doctor, with euthanasia/physician-assisted suicide only allowed for permanent residents, there need to be several requests that are reviewed by a commission and approved by two doctors.[35] | Belgium |

| 2007 | Publication | United States-based non-profit National Quality Forum releases A National Framework for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality Measurement and Reporting. | United States |

| 2007 | Organization | The Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance is founded with the purpose of adressing global care needs at the end-of-life.[10] | |

| 2007 | Advance healthcare directive | To date, 41% of Americans have completed a living will.[43] | United States |

| 2008 | The United States National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization calls for increased access to palliative care in critical care settings.[10] | United States | |

| 2008 | Palliative sedation | The American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs approve an ethical policy regarding the practice of palliative sedation.[44][45] | |

| 2009 | Publication | The United States National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Standards of Practice for Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice along with the companion publication Facts and Figures on Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care in America are released.[10] | United States |

| 2010 | Publication | Paper published in New England Journal of Medicine reveals that patients with non-small-cell lung cancer may live longer with hospice and palliative care.[10] | United States |

| 2010 | Palliative sedation | Svenska Läkaresällskapets, an association of physicians in Sweden, publishes guidelines which allow for palliative sedation to be administered even with the intent of the patient not to reawaken.[46] | Sweden |

| 2013 | Advance healthcare directive | The Beijing Living Will Promotion Association is founded, calling for death with dignity by promoting living wills.[5] | China |

| 2014 | Assisted suicide | Belgium becomes the first country to authorize euthanasia for children, on request, if they have a terminal illness and understand the repercussions of their act.[47] | Belgium |

| 2015 | The United Kingdom ranks highest globally in a study of end-of-life care. A study says "Its ranking is due to comprehensive national policies, the extensive integration of palliative care into the National Health Service, a strong hospice movement, and deep community engagement on the issue." The studies were carried out by the Economist Intelligence Unit and commissioned by the Lien Foundation, a Singaporean philanthropic organization.[48][49] | United Kingdom | |

| 2015 (November) | Assisted suicide | As of date, Belgium has the most liberal assisted suicide laws in the world.[50] | Belgium |

| 2016 | Assisted suicide | Assisted suicide is declared legal in Canada.[51] | Canada |

| 2017 | Publication | A team of Chinese professionals from hospitals compile Palliative Nursing: a guide for oncology nurses, the first textbook to provide evidence-based practice on hospice and palliative care for oncology nurses in China, published by Peking University Medical Press.[5] | China |

| 2017 | Advance healthcare directive | The Italian Senate officially approves a law on advance healthcare directive that would come into force on 31 January 2018.[52][53] | Italy |

| 2018 | Advance healthcare directive | Indian Supreme Court permits living wills and passive euthanasia. The country's apex court holds that the right to a dignified life extends up to the point of having a dignified death.[54] | India |

Visual data

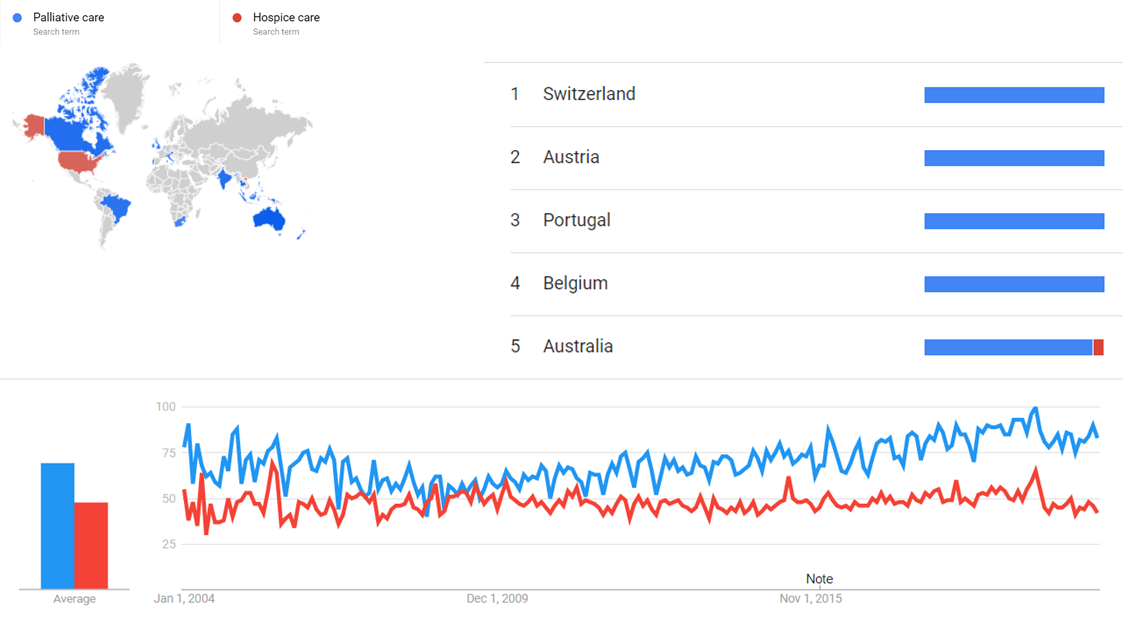

Google Trends

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for Palliative care (search term) and Hospice care (search term), from January 2004 to Month 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[55]

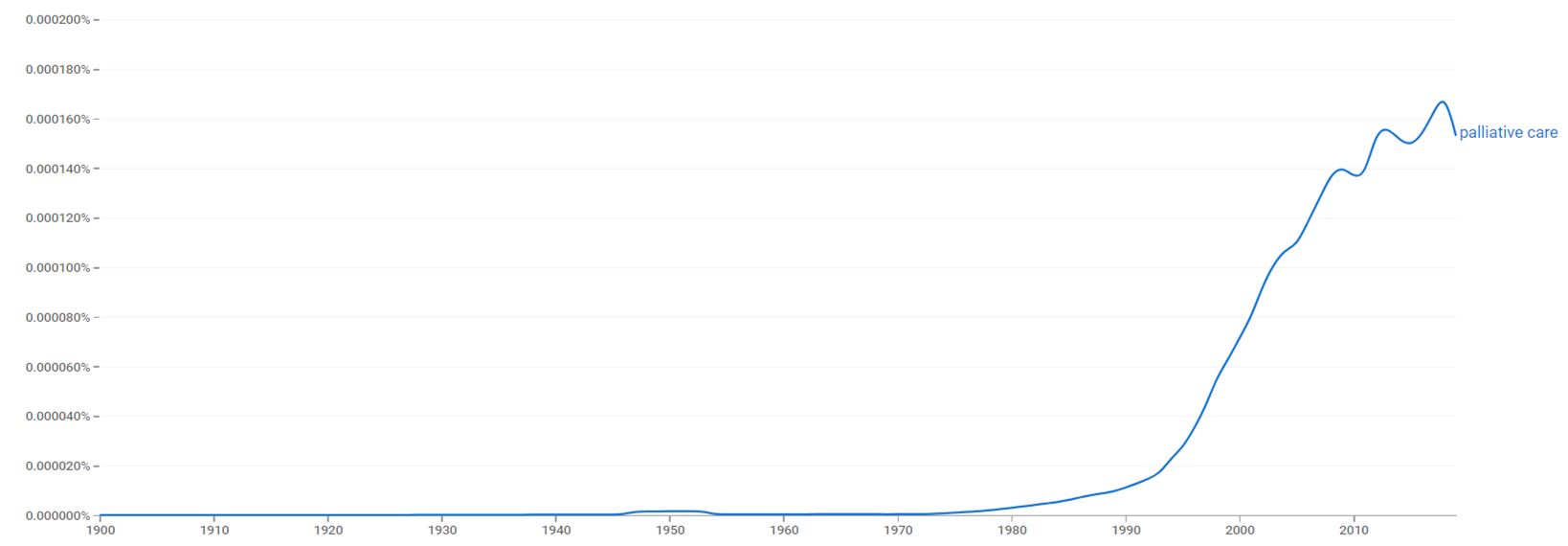

Google Ngram Viewer

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for palliative care, from 1900 to 2019.[56]

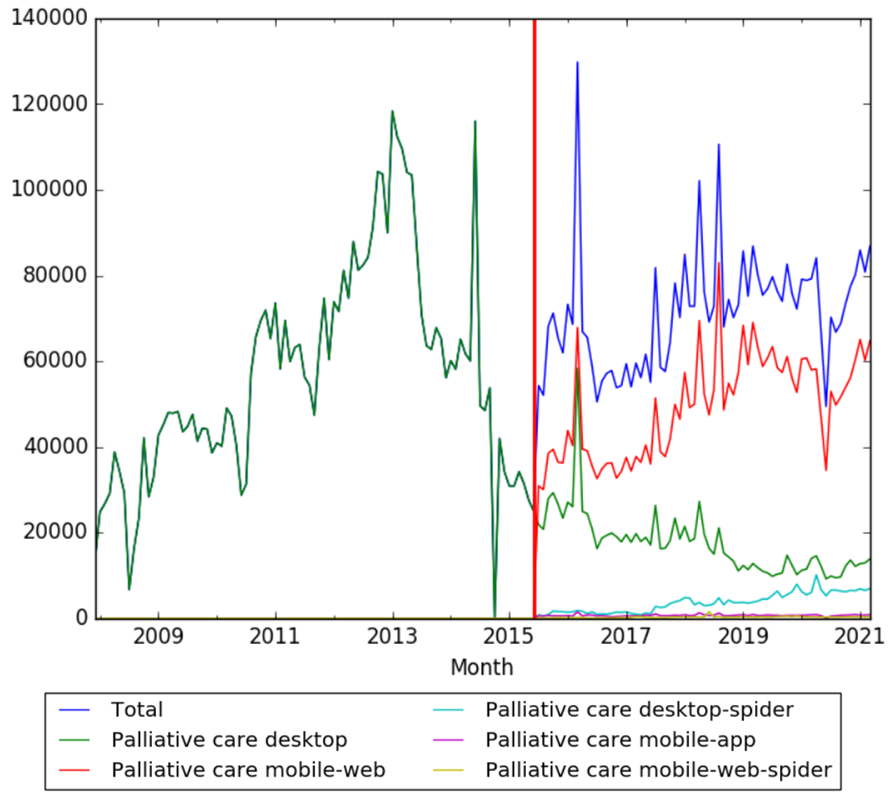

Wikipedia Views

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article palliative care, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to February 2021.[57]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "History of palliative care". pallcare.asn.au. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Saunders, Cicely. "The evolution of palliative care". PMC 1282179. PMID 11535742.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Clark, David. "From margins to centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Historique et principes fondateurs des soins palliatifs". palliabru.be. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Lu, Yuhan; Gu, Youhui; Yu, Wenhua. "Hospice and Palliative Care in China: Development and Challenges". doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_72_17. PMC 5763435. PMID 29379830.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Vanderpool, Harold Y. Palliative Care: The 400-Year Quest for a Good Death.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "The History of Hospice Care and Palliative Care". familycomforthospice.org. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Bruera, Eduardo; Higginson, Irene; F von Gunten, Charles. Textbook of Palliative Medicine.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 "Palliative Care: An Historical Perspective". asheducationbook.hematologylibrary.org. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 "History of Hospice Care". nhpco.org. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Palliative Care Gains Roots in China". omicsonline.org. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "The Hospice Movement in New Zealand - 25 Years On". nathaniel.org.nz. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ Parry, Eldryd High Owen; Richard Godfrey; David Mabey; Geoffrey Gill (2004). Principles of Medicine in Africa (3 revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1233. ISBN 0-521-80616-X.

- ↑ "Objectives". Japan Hospice Palliative Care Foundation. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Ami, S. Ben. "Palliative care services in Israel" (PDF). Middle East Cancer Consortium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-31. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Kapoor, Bimla (October 2003). "Model of holistic care in hospice set up in India". Nursing Journal of India. Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Clinical Pain Management. CRC Press. 2008. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

In 1986, Professor D'Souza opened the first Indian hospice, Shanti Avedna Ashram, in Mumbai, Maharashtra, central India.

- ↑ Iyer, Malathy (Mar 8, 2011). "At India's first hospice, every life is important". The Times Of India. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

The pin drop silence gives no indication that there are 60 patients admitted at the moment in Shanti Avedna Sadan-the country's first hospice that is located on the quiet incline leading to the Mount Mary Church in Bandra.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Wright, Michael; Justin Wood; Tom Lynch; David Clark (November 2006). Mapping levels of palliative care development: a global view (PDF) (Report). Help the Hospices; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Pang, Samantha Mei-che (2003). Nursing Ethics in Modern China: Conflicting Values and Competing Role. Rodopi. p. 80. ISBN 90-420-0944-6.

- ↑ "The Right to Die with Dignity: 1988 General Resolution". Unitarian Universalist Association. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine". omicsonline.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ Lai, Yuen-Liang; Wen Hao Su (September 1997). "Palliative medicine and the hospice movement in Taiwan". Supportive Care in Cancer. 5 (5): 348–350. doi:10.1007/s005200050090. ISSN 0941-4355.

- ↑ "NCCN Palliative Care Guidelines 2007: integrating end-of-life care". healio.com. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Dementias (Charles Duyckaerts, Irene Litvan ed.).

- ↑ Patient Self-Determination Act U.S.C.A. 1395cc & 1396a, 4206-4207, 4751, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, P.L:.b 101-508 (101ST Cong. 2nd Sess. Nov. 5, 1990) (West Supp., 1991).

- ↑ Docker, C. Advance Directives/Living Wills in: McLean S.A.M., Contemporary Issues in Law, Medicine and Ethics," Dartmouth 1996:182.

- ↑ "Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care". charitablechoice.org.hk. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Institute of Palliative Medicine". instituteofpalliativemedicine.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "A short history of palliative medicine in Australia". cancerforum.org.au. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "European Journal of Palliative Care". haywardpublishing.co.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "A palliative care programme in Malaysia". jpalliativecare.com. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Russia's first hospice turns ten". rt.com. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Giger, Joyce Newman. Transcultural Nursing: Assessment and Intervention.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 McDougall & Gorman 2008

- ↑ McLean, S. (1997). Sometimes a Small Victory. Institute of Law and Ethics in Medicine, University of Glasgow.

- ↑ "About APCA". africanpalliativecare.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "About Pallium India-USA". palliumindia.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Right-to-die group convicted of assisting Minnesota suicide". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ NHS National End of Life Care Programme, official website

- ↑ "L'HISTOIRE DES SOINS PALLIATIFS". palliative.ch. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 93

- ↑ Charmaine Jones, With living wills gaining in popularity, push grows for more extensive directive, Crain's Cleveland Business, August 20, 2007.

- ↑ Kevin B. O'Reilly, AMA meeting: AMA OKs palliative sedation for terminally ill, American Medical News, July 7, 2008.

- ↑ American Medical Association (2008), Report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Sedation to Unconsciousness in End-of-Life Care, ama-assn.org; accessed January 5, 2018.

- ↑ Österberg, Lina (October 11, 2010). "Sjuka får sövas in i döden". Dagens Medicin (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 July 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Right to die: terminal divide in state of euthanasia in Europe - BizNews.com". BizNews.com. 2014-12-12. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Quality of Death Index 2015: Ranking palliative care across the world". The Economist Intelligence Unit. 6 October 2015; "UK end-of-life care 'best in world'". BBC. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ The Quality of Death: Ranking end-of-life care across the world, Economist Intelligence Unit, July 2010; Quality of death, Lien Foundation, July 2010; United States Tied for 9th Place in Economist Intelligence Unit's First Ever Global 'Quality of Death' Index, Lien Foundation press release; UK comes top on end of life care - report, BBC News, 15 July 2010

- ↑ "24 & ready to die". The Economist. Economist Group. 10 November 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "2nd Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2017". Health Canada. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "*** NORMATTIVA ***". www.normattiva.it.

- ↑ "Biotestamento. Favorevole o contrario?". ProVersi.it. 19 February 2018.

- ↑ "Death with dignity: on SC's verdict on euthanasia and living wills". 10 March 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ↑ "Palliative care and Hospice care". Google Trends. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ "palliative care". books.google.com. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ↑ "Palliative care". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 4 April 2021.