Timeline of student visa policy in the United States

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

This timeline covers the student visa policy of the United States.

It is a complement to the timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States and timeline of immigrant processing and visa policy in the United States.

Get more details from F visa#History (written by author of this timeline so no need for additional attribution).

Full timeline

| Year | Month and date (if available) | Event type | Affected agencies (past, and present equivalents) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1855 | The Carriage of Passengers Act of 1855 recognizes a separate category of temporary immigrant; students would later be classed this way.[1] | |||

| 1882 | The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 significantly restricts the immigration of Chinese skilled and unskilled laborers, but carves out an exception for students.[1] | |||

| 1913 | The U.S. Bureau of Education records indicate that 4,222 international students were enrolled in 275 U.S. universities, colleges, and technical schools; most of them were sent by foreign governments for education and training that would be useful when the students returned home.[1] | |||

| 1918 | All noncitizens are required to obtain visas prior to entry to the United States.[2] | |||

| 1919 | The Institute of International Education is formed to protect and promote the interests of international students and exchange visitors.[1] | |||

| 1921 | Lobbying by the IIE leads to the classification of students as nonimmigrants and the creation of a separate nonimmigrant visa for students, thereby exempting students from the numerical quotas placed in the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924.[1][3] | |||

| 1924 | The United States Congress requires consular officers to make a determination of admissibility prior to issuing a visa.[2] | |||

| 1952 | June 27 | Legislation | The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 becomes law after both chambers of the 82nd United States Congress vote to override the veto of President Harry S. Truman. Among other things, this Act begins the processing of formalizing non-immigrant classifications using letters of the alphabet; student status gets the letter F.[4] | |

| 1961 | September 21 | Legislation | The Fulbright–Hays Act of 1961, also known as the Mutual Exchange and Cultural Exchange Act of 1961 (MECEA), is signed into law by President John F. Kennedy after passing both chambers of the 87th United States Congress. The Act encourages mutual education and cultural exchange between the United States and other countries, and in particular, leads to the creation of the J-1 visa category. The J-1 visa category would be used for some students and scholars instead of student visas.[5] | |

| 1978 | November 16 (final rule), January 1, 1979 (effective date) | Regulation (final rule) | Immigration and Naturalization Services, present equivalent: ICE SEVP | A new rule related to foreign students is included in the Federal Register. p. 54618 onward. The new rule implements "duration of status" for students (effective January 1979), allowing students to get visas to study for more than one year, and also provide updated details related to temporary absence, extensions (using Form I-538), employment, and practical training; this appears to provide the first articulation of Optional Practical Training. As of this time, the I-20 and I-94 are already in use.[6][7] |

| 1981 | January 23 (final rule), February 23 (effective date) | Regulation (final rule) | Immigration and Naturalization Services, present equivalent: ICE SEVP | A final rule related to foreign students temporarily rolls back the introduction of "duration of status" in the 1978 rule. From now on, the student's I-94 end date is to be based on the I-20 end date as of the time of issuance of the I-94.[8][7] |

| 1981 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services, present equivalent: ICE SEVP | Public Law 97-116, the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1981, is passed by the 97th United States Congress.[9] Among other things, these create a new M-1 visa for students of non-academic (vocational) courses.[10] | |

| 1983 | February 25 | Regulation (final rule) | Immigration and Naturalization Services, present equivalent: ICE SEVP | A lengthy rule from INS reinstates duration of status for F-1 students, but limits duration of status to the period of time during which the student is pursuing a full course of study in only one educational program. The rule also provides details on the M-1 status created by the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1981.[10][7] |

| 1987 | March 23 | Regulation (final rule) | Immigration and Naturalization Services, present equivalent: ICE SEVP | A final rule from INS updates some guidelines around the boundary cases for students staying in status.[11][7] |

| 1989 | April 11 | Executive Order 12711 is issued by President George H. W. Bush. It defers deportation of Chinese nationals and their direct dependents who were in the US between 5 June 1989 and 11 April 1990, waives the 2-year home country residency requirement, and gives them employment authorization through 1 January 1994. In particular, this Act affects students, who constitute a large fraction of Chinese nationals temporarily present in the United States. | ||

| 1992 | October 9 | The Chinese Student Protection Act of 1992 is signed into law by President George H. W. Bush. It formalizes the protections created by Executive Order 12711. | ||

| 1993 | February 26 | Violence | The 1993 World Trade Center bombing occurs. It is discovered that Eyad Ismoil, one of the terrorists, is in the United States on an expired student visa.[1][12] | |

| 1994 | September 24 | A memorandum from the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Investigative Agency Policies to the Deputy Attorney General dated September 24, 1994, mentions the need to subject foreign students to thorough and continuing scrutiny before and during their stay in the United States.[12] | ||

| 1995 | On April 17, the Deputy Attorney General asks the INS Commissioner to address the issues from the Department of Justice report. The INS forms a task force in June 1995 to conduct a comprehensive review of the F, M, and J visa processes. Besides the INS, the task force includes members from the State Department and the United States Information Agency, and experts in the administration of international student programs.[12] The task force report, issued on December 22, 1995, identified problems in the tracking and monitoring of students by schools, problems in the certification of schools by the INS, and problems with INS receiving and maintaining up-to-date records from schools.[12] Based on this, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) directs the Attorney General, in consultation with the Secretary of State, to develop and conduct a program to collect certain information on nonimmigrant foreign students and exchange visitors from approved institutions of higher education and designated exchange visitor programs.[12][1] | |||

| 1997 | June | The INS launches a pilot program for a centralized electronic reporting system for institutions, called the Coordinated Interagency Partnership Regulating International Students (CIPRIS). The CIPRIS pilot would officially end in October 1999, as the INS felt it had gathered enough data from the prototype to start working on the nationwide system.[12][7] | ||

| 1999 | Based on experience gathered from the CIPRIS pilot, the INS begins work on what would be called the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), with the associated information system called the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS). SEVIS meets with considerable initial opposition from the Association of International Educators and American Council on Education, but they claim that their opposition is not to the program in principle but concern that a botched rollout could affect many students.[1][12] | |||

| 2000 | November | Guidance | The U.S. Department of State transmits the first version of the Technology Alert List (TAL) as a guideline for consular officers when reviewing visa applications. The purpose of this guideline is to prevent the export of "goods, technology, or sensitive information" through activities such as "graduate-level studies, teaching, conducting research, participating in exchange programs, receiving training or employment..."; the guidance would be considered responsible for the greater rejection rate of visa applications in subjects with potential application to military and other state uses.[13][14] | |

| 2001 | September and October | Violence | In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks (September 11, 2001) and the Patriot Act (October 26, 2001), there is increased momentum in favor of SEVIS. This is partly because one of the attackers, Hani Hanjour, had come to the United States on a student visa.[1][12][15] | |

| 2002 | April 12 | Regulation (final rule) | An interim final rule is announced, requiring anybody on a B visa to transition to a F or M visa prior to starting a program of study. Moreover, people on B status could transition using Form I-539 (i.e., change status while in the US) only if their visa had an annotation indicating that they might transition to student status.[16][1] | |

| 2002 | May 7 | A Presidential Directive calls for the creation of the Interagency Panel on Advanced Science and Security (IPASS). The intent of IPASS is to help with the evaluation of suspicious visa applications in subjects that have implications for national security.[1][17] | ||

| 2002 | May 16 | A proposed rule is announced on this date: Retention and reporting requirements for F, J, and M nonimmigrants; Student and Exchange Visitor Information System[18] | ||

| 2002 | July 1 | An interim final rule is announced on this date: Allowing eligible schools to apply for preliminary enrollment in SEVIS[19] | ||

| 2002 | August | A cable from the U.S. Department of State updates the Technology Alert List originally published in November 2000, and provides additional guidance for its use in cases that may fall under INA section 212(a)(3)(a), which renders inadmissible aliens who there is reason to believe are seeking to enter the U.S. to violate U.S. laws prohibiting the export of goods, technology or sensitive information from the U.S.[13] | ||

| 2002 | September 11 | The Interim Student and Exchange Authentication System (ISEAS), an interim program by the United States Department of State, comes into force. This is a temporary system put in place until SEVIS goes live.[20] | ||

| 2002 | September 25 | An interim final rule is announced on this date: Requiring certification of all service-approved schools for SEVIS enrollment[21] | ||

| 2002 | November 2 | Legislation | Immigration and Naturalization Services; present equivalent: ICE SEVP | The Border Commuter Student Act (Public Law 107-274) is signed into law, creating the F-3 and M-3 nonimmigrant visa category for border commuters who are citizens or residents of Canada or Mexico and commute to the United States for full-time or part-time study at a DHS-approved school. Family members of these students are not entitled to derivative F-2 or M-2 status. Formerly, these students would have been admitted as visitors; the move to creating a separate status is to better track them in light of heightened security concerns in a post-9/11 world.[22][23] |

| 2002 | December 11 | An interim final rule is announced on this date: Retention and reporting of information for F, J, and M nonimmigrants; SEVIS[24] | ||

| 2003 | January 31 | Mandatory SEVIS use begins on this date.[1] | ||

| 2006 | August | Out of 17 Egyptian students who arrive on July 29, 2006 in the United States, due to report at Montana State University for a one-month exchange program, only 6 show up at the university. Of the 11 missing students, 9 are apprehended by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement with help from the FBI for administrative immigration violations.[25] None of them are found to have terrorist or criminal connections, and Dean Boyd, a spokesman for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency, says the missing students "had no intention of attending the program and simply wanted to earn more money and stay and look for a better life in America."[26] A Congressional Research Service report would cite this as a claimed success of SEVIS as a recordkeeping system.[7] | ||

| 2020 | January 29 | Guidance | ICE SEVP | U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement issues its first guidance related to the COVID-19 pandemic, before it has reached a pandemic stage. The guidance is relevant for students currently in parts of the world affected by COVID-19.[27] |

| 2020 | March 9, March 13 | Guidance | ICE SEVP | In two pieces of guidance published on March 9 and March 13, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement temporarily modifies the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The guidance allows students in F-1 or M-1 status to retain student status while staying in the United States if their school is temporarily closed due to COVID-19, and to maintain status by enrolling in courses online if their school switches coursework to online, whether inside or outside the United States.[28][29] This temporary modification is extended through the spring and summer, but an announcement on July 6, 2020 partially repeals it for the autumn (fall) of 2020. |

| 2020 | July 6 | Guidance | ICE SEVP | U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement partially rolls back temporary modifications made to the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, with the rolled back version applicable starting with the autumn (fall). With the modified guidance, international students in F-1 or M-1 status must be enrolled in at least one in-person course in order to continue to stay in the United States; however, if their school is offering a hybrid of in-person and online coursework, they can take some courses online and count those toward credit requirements.[30] Multiple lawsuits are filed by universities against ICE for this rollback.[31] |

| 2020 | July 14 (preliminary announcement), July 24 (official guidance) | Guidance | ICE SEVP | U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement rescinds its July 6 order, thereby reinstating the full set of temporarily modifications made to the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.[32][33] |

| 2021 | April 26 | Guidance | ICE SEVP | U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement announces that the guidance originally issued in March 2020 for the Student and Exchange Visitor Program will continue to apply for the 2021-2022 academic year.[34][35] |

Visual data

Google Trends

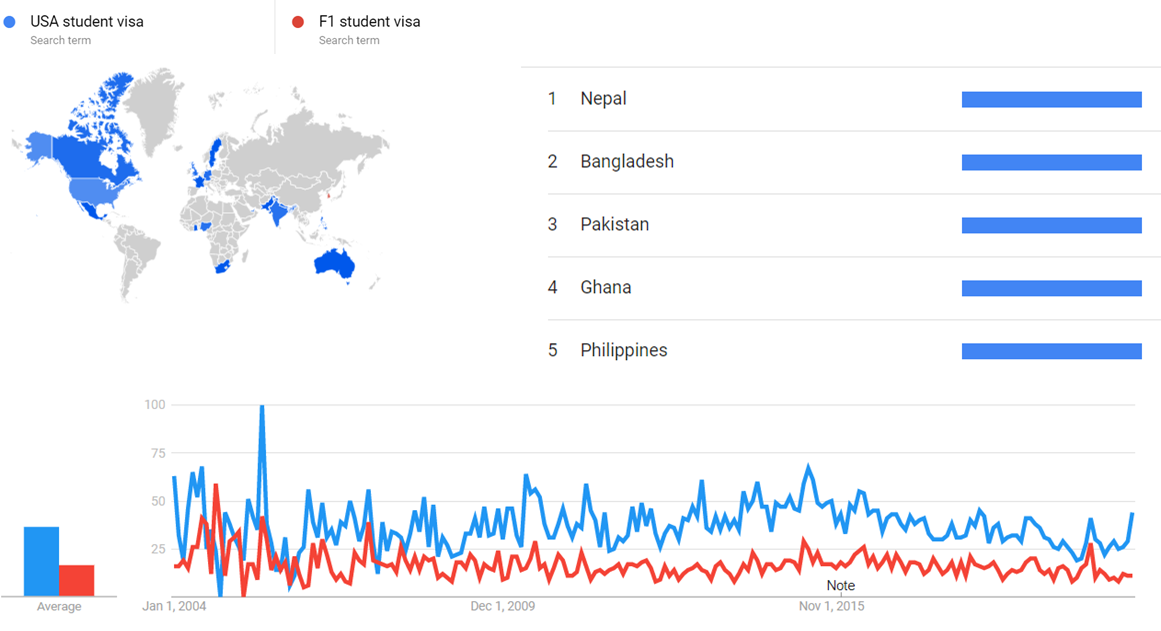

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data for USA student visa (Search term) and F1 student visa (Search term), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[36]

Google Ngram Viewer

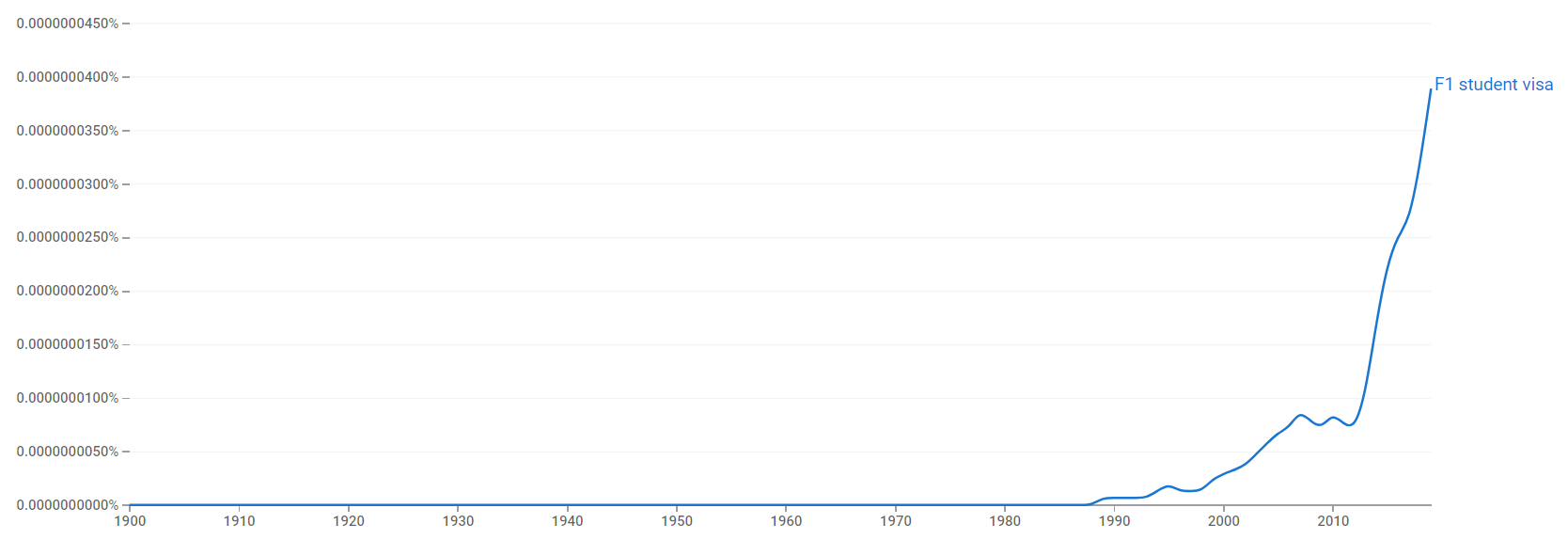

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for F1 student visa, from 1900 to 2019.[37]

See also

- Timeline of immigrant processing and visa policy in the United States

- Timeline of immigration enforcement in the United States

References

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Brief of Amicus Curiae Law Professors in Support of Respondent (Kerry v. Din)" (PDF). American Bar Association.

- ↑ "A Brief History of IIE". Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Public Law 414: Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952" (PDF). June 27, 1952. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Mutual Education and Cultural Exchange Program" (PDF). Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Federal Register: 43 Fed. Reg. 54617 (Nov. 22, 1978)". November 22, 1978. pp. 54618–54621. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Haddal, Chad (January 31, 2008). "Foreign Students in the United States: Policies and Legislation" (PDF). Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Federal Register: 46 Fed. Reg. 7257 (Jan. 23, 1981)". January 23, 1981. pp. 7267–7268. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "H.R.4327 - Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1981". United States Congress. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Federal Register: 48 Fed. Reg. 14561 (Apr. 5, 1983)" (PDF). April 5, 1983. pp. 14575–14594. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Federal Register: 52 Fed. Reg. 13215 (Apr. 22, 1987)". April 22, 1987. pp. 13222–13229. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 "CHAPTER SIX. THE INS'S FOREIGN STUDENT PROGRAM". May 20, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Technology Alert List" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. August 1, 2002. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Technology Alert List". Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Farley, Robert (May 10, 2013). "9/11 Hijackers and Student Visas". Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Requiring Change of Status From B to F–1 or M–1 Nonimmigrant Prior to Pursuing a Course of Study; Final Rule Limiting the Period of Admission for B Nonimmigrant Aliens; Proposed Rule" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, in the Federal Register. April 12, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Proposed New Department Complicates Outlook for Visas". American Physical Society. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Retention and Reporting of Information for F, J, and M Nonimmigrants; Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Federal Register. May 16, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Allowing Eligible Schools To Apply for Preliminary Enrollment in the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS); Interim Final Rule" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Federal Register. July 1, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ Croom, Patty; Ellis, Jim. "A Glossary of SEVIS-Related Terminology" (PDF). Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Requiring Certification of all Service Approved Schools for Enrollment in the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Federal Register. September 25, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "9 FAM 402.5 (U) STUDENTS AND EXCHANGE VISITORS – F, M, AND J VISAS". Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "DOS Describes Border Commuter Student Act". American Immigration Lawyers Association. December 3, 2002. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Retention and Reporting of Information for F, J, and M Nonimmigrants; Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS); Final Rule" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Federal Register. December 11, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Nine Egyptian students in U.S. custody". CNN. August 12, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ Korry, Elaine (August 17, 2006). "Web-Based System Finds Missing Foreign Students". Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Broadcast Message: 2019 Novel Coronavirus and F and M nonimmigrants" (PDF). U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. January 29, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ "Broadcast Message: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Potential Procedural Adaptations for F and M nonimmigrant students" (PDF). U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. March 9, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ "COVID-19: Guidance for SEVP Stakeholders" (PDF). U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. March 13, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "SEVP modifies temporary exemptions for nonimmigrant students taking online courses during fall 2020 semester". U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ Redden, Elizabeth (July 13, 2020). "More Lawsuits Challenge ICE International Student Rule". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ Dickler, Jessica (July 14, 2020). "Trump administration reverses course on foreign student ban". CNBC. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ "Broadcast Message: Follow-up: ICE continues March Guidance for Fall School Term" (PDF). U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ↑ "Updates on Fall 2021 SEVP COVID-19 Guidance". NAFSA. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ . U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. April 26, 2021 https://www.ice.gov/doclib/coronavirus/covid19faq.pdf. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "USA student visa and F1 student visa". Google Trends. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "F1 student visa". books.google.com. Retrieved 21 April 2021.