Difference between revisions of "Timeline of leukemia"

(→Visual data) |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | == | + | == Numerical and visual data == |

| + | |||

| + | === Google Scholar === | ||

| + | |||

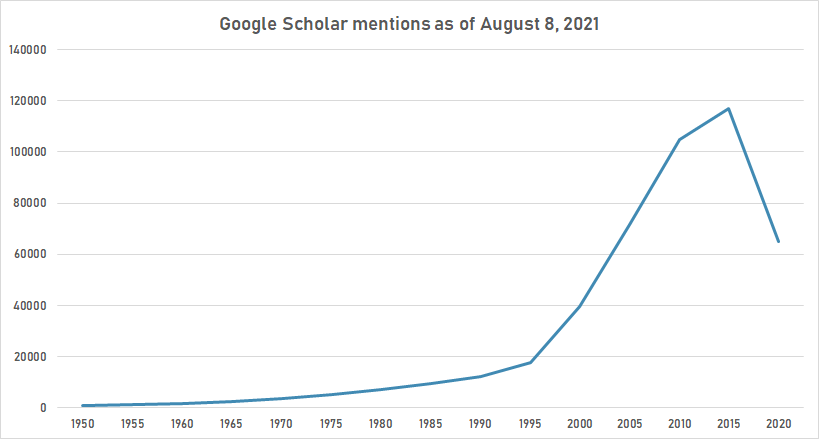

| + | The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of August 8, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| + | ! Year | ||

| + | ! leukemia | ||

| + | ! lymphoma | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1950 || 1,080 || 284 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1955 || 1,290 || 545 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1960 || 2,160 || 839 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1965 || 3,210 || 1,450 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1970 || 4,850 || 2,650 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1975 || 7,960 || 4,360 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1980 || 12,000 || 7,570 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1985 || 17,900 || 12,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1990 || 24,100 || 15,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1995 || 38,200 || 21,800 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2000 || 64,300 || 40,500 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2005 || 105,000 || 73,100 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2010 || 136,000 || 95,900 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2015 || 159,000 || 125,000 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 2020 || 67,200 || 68,100 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Kidney cancer google schoolar.png|thumb|center|700px]] | ||

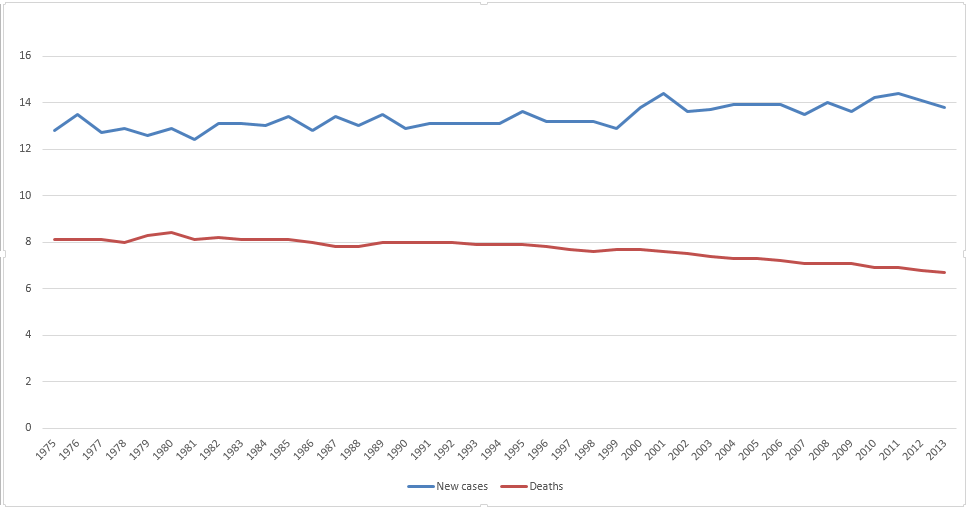

[[File:Leukemia cases in the USA.png|400px|thumb|center|Evolution of new leukemia cases and deaths per 100,000 people in the United States for the period 1975-2013, according to the [[wikipedia:National Cancer Institute|National Cancer Institute]]. Age-adjusted.<ref>{{cite web|title=Leukemia cases USA|url=https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ld/leuks.html|website=cancer.gov|accessdate=21 November 2016}}</ref>]] | [[File:Leukemia cases in the USA.png|400px|thumb|center|Evolution of new leukemia cases and deaths per 100,000 people in the United States for the period 1975-2013, according to the [[wikipedia:National Cancer Institute|National Cancer Institute]]. Age-adjusted.<ref>{{cite web|title=Leukemia cases USA|url=https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ld/leuks.html|website=cancer.gov|accessdate=21 November 2016}}</ref>]] | ||

| Line 37: | Line 80: | ||

[[File:Leukemia wv.png|thumb|center|400px]] | [[File:Leukemia wv.png|thumb|center|400px]] | ||

| − | |||

==Full timeline== | ==Full timeline== | ||

Revision as of 13:10, 8 August 2021

This is a timeline of leukemia, describing especially major discoveries and advances in treatment against the disease.

Contents

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Prior to 1800 | Various cancers, including leukemia, are described in ancient Egyptian texts dating back to 3000 BC. Translations inform "large, protruding mass" or "thick blood" and describe the disease as "there is no treatment." This basic understanding of leukemia and cancer lasts for millennia.[1] |

| 19th Century | Discovery of leukemia. Velpeau (1825), Donné (1844), Bennett (1845), Craigie (1845), Virchow (1845), and Fuller (1846), establish the possibility that sustained leukocytosis could occur in the absence of infection. The term leukemia is adopted to describe such conditions.[2][3][4] It is discovered that leukemia originates in the bone marrow. Histologic stains for microscopic study are introduced.[2] |

| 1900s | Leukemia is subdivided in four primary types: acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[5][6] |

| 1940s–present | Era of chemotherapy development, also the first effective leukemia treatments with drugs introduced by Sidney Farber.[3][7][8] Childhood leukemia is thought to be on a constant rise in the 20th and 21st century.[9] In 2010, globally, approximately 281,500 people died of leukemia.[10] In 2000, approximately 256,000 children and adults around the world developed a form of leukemia, and 209,000 died from it.[11] DNA and genetic analysis have opened a new chapter in leukemia treatments.[9] |

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of August 8, 2021.

| Year | leukemia | lymphoma |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 1,080 | 284 |

| 1955 | 1,290 | 545 |

| 1960 | 2,160 | 839 |

| 1965 | 3,210 | 1,450 |

| 1970 | 4,850 | 2,650 |

| 1975 | 7,960 | 4,360 |

| 1980 | 12,000 | 7,570 |

| 1985 | 17,900 | 12,800 |

| 1990 | 24,100 | 15,800 |

| 1995 | 38,200 | 21,800 |

| 2000 | 64,300 | 40,500 |

| 2005 | 105,000 | 73,100 |

| 2010 | 136,000 | 95,900 |

| 2015 | 159,000 | 125,000 |

| 2020 | 67,200 | 68,100 |

Google Trends

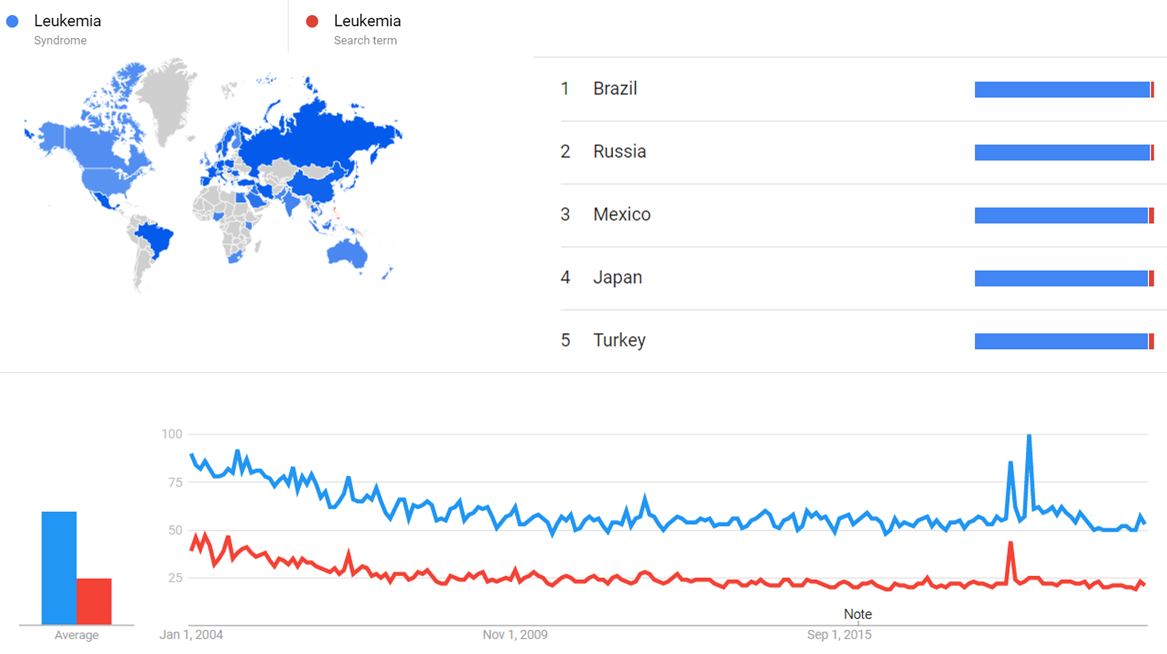

The comparative chart below shows Google Trends data Leukemia (Syndrome) and Leukemia (Search Term), from January 2004 to March 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[13]

Google Ngram Viewer

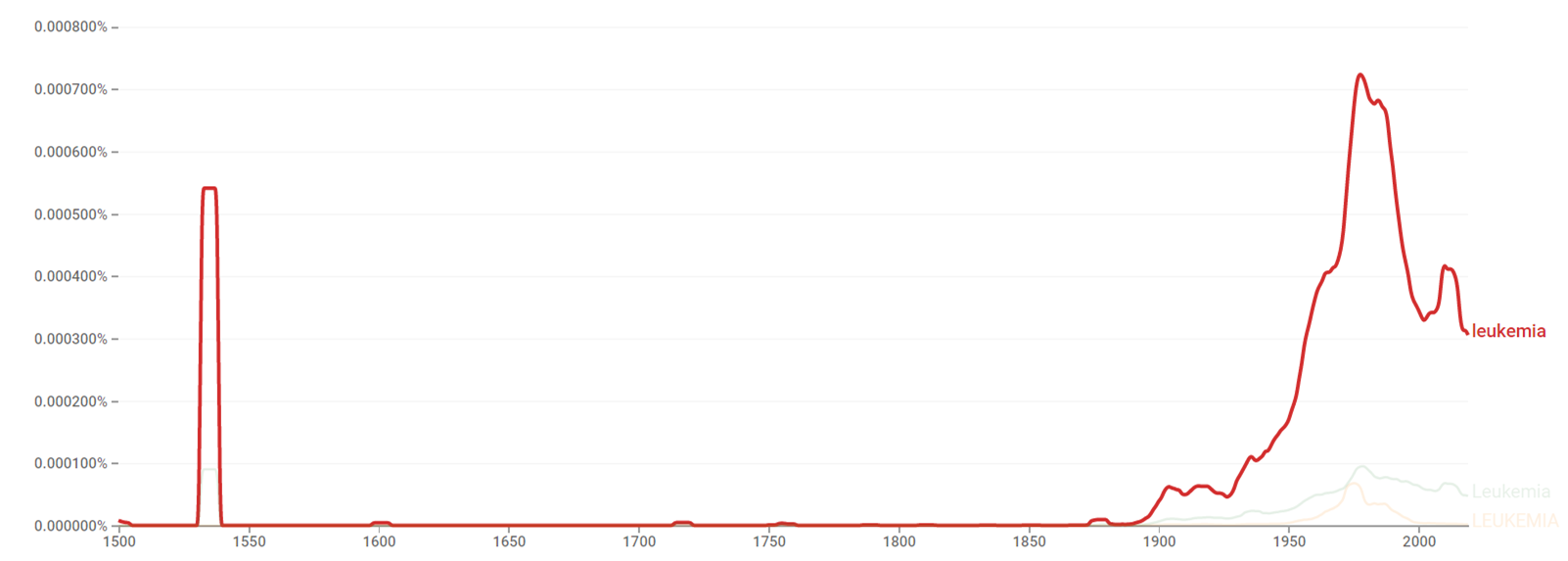

The chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Leukemia, from 1500 to 2019.[14]

Wikipedia Views

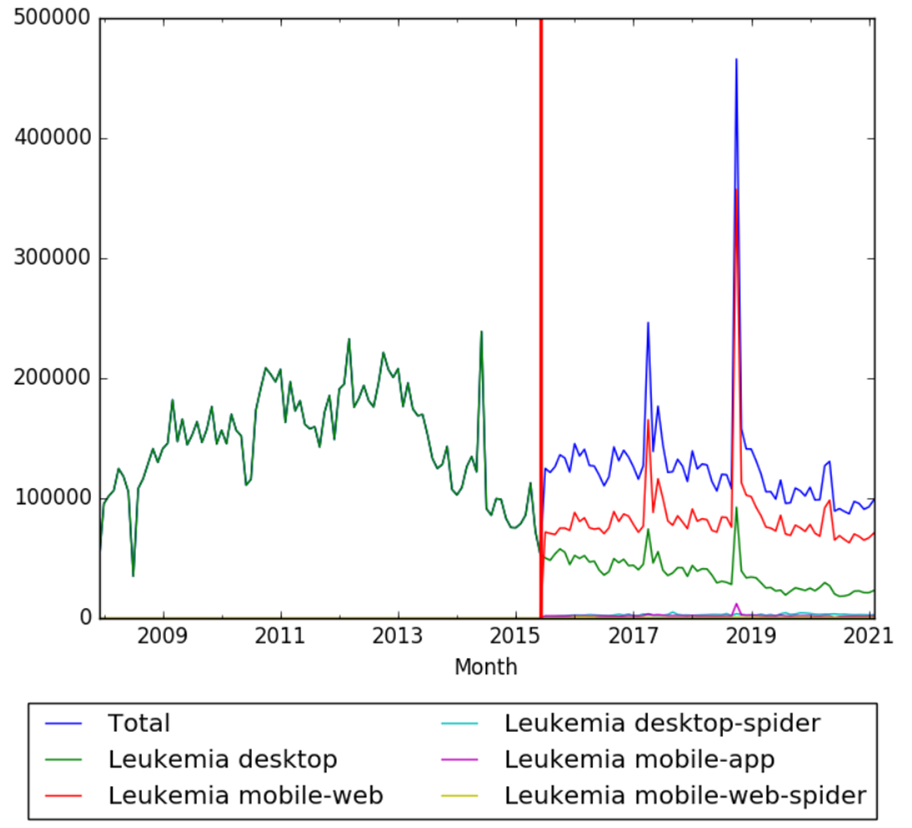

The chart below shows pageviews of the English Wikipedia article Leukemia, on desktop from December 2007, and on mobile-web, desktop-spider, mobile-web-spider and mobile app, from July 2015; to February 2021.[15]

Full timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1749 | Discovery | French physician Joseph Lieutaud first notes white cells, calling them globuli albicantes.[16] | |

| 1774 | Development | English surgeon William Hewson publishes work on the lymphatic system and first describes the lymphocyte.[16] | United Kingdom |

| 1811 | Development | Peter Cullen defines a case of splenitis acutus with unexplainable milky blood.[17] | Edinburgh, Scotland |

| 1825 | Development | French surgeon Alfred Velpeau defines the leukemia associated symptoms, and observes pus in the blood vessels.[17] | |

| 1844 | Discovery | French bacteriologist Alfred Donné detects a maturation arrest of the white blood cells.[17] | |

| 1845 | Development | English physician John Bennett renames splenitis acutus to leucocythemia, based on the microscopic accumulation of purulent leukocytes.[17][18] | |

| 1845–1847 | Development | German physician Rudolf Virchow defines a reversed white and red blood cell balance. Virchow introduces the term leukemia for the disease (leukämie in German).[2][17] | |

| 1868 | Discovery | German pathologist Ernst Neumann reports changes in the bone marrow in leukaemia and establishes the link between the source of blood and the bone marrow.[3] | Königsberg, Prussia |

| 1877 | Medical development | Swiss pathologist Paul Ehrlich develops methods for staining tissue, making possible to distinguish between different types of blood cells, thus leading to the capability to diagnose numerous blood diseases.[2][3][4] | Germany |

| 1879 | Medical development | F. Mosler first describes the technique of bone marrow examination to diagnose leukemia.[4] | |

| 1889 | Development | German physician Wilhelm Ebstein introduces the term acute leukemia to differentiate rapidly progressive and fatal leukemias from the more indolent chronic leukemias.[4] | Prussia |

| 1900 | Development | Swiss hematologist Otto Naegeli refines the classification of leukemia by dividing it into myelogenous and lymphocytic classes.[2][3][4] | |

| 1936 | Medical development | American hematologist John H. Lawrence of the University of California, Berkeley introduces phosphorus-32 for the treatment of leukemia.[19][20][21] | United States |

| 1946 | Organization | Leukemia Research Foundation is established. It is dedicated to combating all blood cancers by funding research.[22] | Northfield, Illinois, United States |

| 1947 | Discovery | American pediatric pathologist Sidney Farber discovers that aminopterin can induce remissions in acute lymphocytic leukemia in children, leading to the development of a new category of chemotherapy drugs, called antimetabolites, that impair the ability of cancer cells to grow and replicate. It is considered the first effective leukemia treatment.[8] | |

| 1949 | Organization | Leukemia & Lymphoma Society is founded. It is the world's largest voluntary health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research, education and patient services.[23][24] | Rye Brook, New York (serves the United States and Canada) |

| 1949–1956 | Discovery | Researchers discover ways to protect the body from radiation damage by shielding a mouse's spleen from radiation. Eventually, it is learned that the body recruits stem cells, which are found in the spleen and bone marrow, to protect and heal itself from radiation damage.[8] | |

| 1957 | Development | Researchers report the first bone marrow transplantation for treating leukemia, although with poor results. It would not be until the late 1970s when marrow transplantation becomes successful due to tissue matching.[25] | United States |

| 1958 | Discovery | Scientists find that a combination of the drugs 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate can reduce or eliminate cancer growth and extend survival in patients with leukemia. It is discovered that carefully honed drug combinations can attack cancer cells from different angles.[8] | United States |

| 1960–1969 | Discovery | Various studies show that the drug cytarabine (ara-C) has activity against leukemias and provides a major boost to combination chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia.[8] | |

| 1960 | Discovery | Researchers identify a chromosomal abnormality linked to many leukemias. A decade later, it is discovered that this abnormality results when parts of chromosomes 9 and 22 switch places in a phenomenon called translocation.[8] | Philadelphia, United States |

| 1961 | Discovery | Researchers demonstrate that drug vinblastine blocks a key protein involved in cancer cell division and induces some leukemias and lymphomas into remission. Vinblastine is approved by the FDA.[8] | United States |

| 1963 | Development | Vincristine, a sister drug to vinblastine, is approved by the FDA.[8] | United States |

| 1965 | Organization | The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) is founded as an intergovernmental agency forming part of the World Health Organization of the United Nations. Its role is to conduct and coordinate research into the causes of cancer.[26] | Lyon, France |

| 1974 | Development | Antibiotic doxorubicin is approved by the FDA to treat many cancer types, including some leukemias. Together with cytarabine, doxorubicin induces acute myeloid leukemia remissions by damaging the DNA of cancer cells.[8] | United States |

| 1977 | Discovery | Chemotherapy drug chlorambucil is found to slow the progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, the second most common type of leukemia in adults.[8] | |

| 1980 | Discovery | Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-I) is identified. It is the first virus that causes cancer being discovered.[27][28] | |

| 1982 | Discovery | A large trial shows that using the anthracycline daunorubicin, in combination with cytarabine, is more effective at causing complete remissions of acute myeloid leukemia than the previously-standard drug, doxorubicin.[8] | |

| 1986 | Organization | The National Marrow Donor Program is established as a nonprofit organization. It operates the world's largest registry of unrelated adult donors and umbilical cord blood units, which contain stem cells that can help save the lives of some patients with blood-related cancers.[8] | St. Paul, Minnesota, United States |

| 1986–1989 | Discovery | Scientists find that occupational exposure to benzene is associated with increased risk of developing non-lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and other diseases.[8] | |

| 1988 | Organization | The José Carreras Leukaemia Foundation is founded by tenor José Carreras. It finances national and international scientific research projects, among other activities.[29] | Barcelona, Spain (branches in United States, Switzerland and Germany) |

| 1989 | Organization | The Simon Flavell Leukaemia Research Laboratory is founded. It aims at supporting children and adults who have been diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma, and conducting research programmes into new antibody-based treatments.[30][31] | Southampton, United Kingdom |

| 1990–1994 | Development | Fludarabine is introduced, and proven effective for patients who do not respond to chlorambucil for treating leukemia.[8][32] | |

| 1993 | Treatment | Stem cell transplantation for treating leukemia is performed for the first time.[33][34] | |

| 1995 | Discovery | Researchers discover that Lymphocyte transfusions from a biologically matched, healthy donor to a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia can help drive the leukemia back into remission if the cancer returns after a previous stem cell or bone marrow transplant from the same donor.[8] | |

| 1995 | Discovery | Tretinoin is found to cause remission in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia.[8] | |

| 2000 | Discovery | Large clinical trial demonstrates that drug fludarabine, which was originally developed as a back-up therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, works in more patients and produces longer lasting remissions than previous standard drug, chlorambucil.[8] | |

| 2001 | Treatment | The FDA approves imatinib after the drug is shown to halt the growth of chronic myelogenous leukemia in the majority of patients.[8] | United States |

| 2004–2006 | Development | Epigenetic drugs azacytidine and decitabine are approved by the FDA to prevent cancer in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, a group of blood disorders that predispose a person to acute myelogenous leukemia.[8] | United States |

| 2005 | Treatment | FDA approves palifermin to reduce oral sores associated with chemotherapy in patients with blood cancers.[8] | |

| 2006 | Discovery | Dasatinib is found to help as second targeted treatment for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia who cannot tolerate or develop resistance to imatinib.[8] | |

| 2008 | Development | Acute Myeloid Leukemia becomes the first cancer genome to be fully sequenced. DNA is extracted from leukemic cells and compared to unaffected skin. Acquired mutations in several genes that have not previously been associated with the disease are found in leukemic cells.[4] | |

| 2011 | Discovery | A large trial establishes that progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia slows and survival improves after adding targeted drug rituximab to initial treatment with standard drug fludarabine.[8] | |

| 2017 | Treatment | The United States Food and Drug Administration approves the first gene therapy, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), for refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.[35] | United States |

See also

References

- ↑ "History of Leukemia". Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "The leukemias". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Leukaemia – a brief historical review from ancient times to 1950". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Acute Myeloid Leukemia History". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ "Leukemia types". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "La historia de la leucemia". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Sidney Farber". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 "Leukemia Progress & Timeline". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "History of leukemia". Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. December 2012. PMID 23245604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

- ↑ Mathers, Colin D, Cynthia Boschi-Pinto, Alan D Lopez and Christopher JL Murray (2001). "Cancer incidence, mortality and survival by site for 14 regions of the world" (PDF). Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper No. 13. World Health Organization.

- ↑ "Leukemia cases USA". cancer.gov. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Leukemia". Google Trends. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ "Leukemia". books.google.com. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ "Leukemia". wikipediaviews.org. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Leukaemia – a brief historical review from ancient times to 1950". Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Kampen, KR (Jan 2012). "The discovery and early understanding of leukemia.". Leuk Res. 36: 6–13. PMID 22033191. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2011.09.028.

- ↑ "splenitis acutus". Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ Marks, Geoffrey; Beatty, William K. The Precious Metals of Medicine.

- ↑ Oreskes, Naomi; Krige, John. Science and Technology in the Global Cold War.

- ↑ Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Sciences (Dale L. Bailey, David W. Townsend, Peter E. Valk, Michael N. Maisey ed.).

- ↑ "Leukemia Research Foundation". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ "Leukemia Organizations". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society". Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ Tetsuya, Ishii; Koji, Eto (2014). "Fetal stem cell transplantation: Past, present, and future". World J Stem Cells. 6: 404–20. PMC 4172669

. PMID 25258662. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v6.i4.404.

. PMID 25258662. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v6.i4.404.

- ↑ "IARC". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Matsuoka, M (2005). "Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I) infection and the onset of adult T-cell leukemia (ATL)". Retrovirology. 2: 27. PMC 1131926

. PMID 15854229. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-2-27.

. PMID 15854229. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-2-27.

- ↑ "Fifty Years of Milestones in Cancer Research". Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "José Carreras foundation". Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "David Flavell". Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "Simon Flavell Leukaemia Research Laboratory research". Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ Rai, KR; Peterson, BL; Appelbaum, FR; et al. (December 2000). "Fludarabine Compared with Chlorambucil as Primary Therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia". New England Journal of Medicine. 343: 1750–1757. PMID 11114313. doi:10.1056/NEJM200012143432402.

- ↑ Aversa, F; Terenzi, A; Felicini, R; Carotti, A; Falcinelli, F; Tabilio, A; Velardi, A; Martelli, MF. "Haploidentical stem cell transplantation for acute leukemia.". Int J Hematol. 76 Suppl 1: 165–8. PMID 12430847. doi:10.1007/bf03165238.

- ↑ "Fifty Years of Milestones in Cancer Research". Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Past and Future of Gene Therapy". specialtypharmacytimes.com. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

Category:Leukemia Category:Health-related timelines Category:Medicine timelines