Timeline of cervical cancer

From Timelines

The content on this page is forked from the English Wikipedia page entitled "Timeline of cervical cancer". The original page still exists at Timeline of cervical cancer. The original content was released under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License (CC-BY-SA), so this page inherits this license.

This is a timeline of cervical cancer, describing especially major discoveries and advances in treatment of the disease.

Contents

Big picture

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 19th century | Cervical cancer is identified as a sexually transmitted disease. At the end of the century, surgery is introduced for treating the disease. |

| Early 20th century | Epidemiologists discover that cervical cancer is common in female sex workers and also common in women whose husbands have a high number of sexual partners or were regular customers of prostitutes.[1] |

| 1920s | Papanikolaou develops his eponymous technique. The colposcope is developed. |

| 1940s | Pap smear screening begins. |

| 1980s | First concrete evidence that specific Human Papillomavirus (HPV) types are linked to cervical cancer.[1] Tobacco use is linked to cervical cancer. |

| 2000s | First Human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine is released. Several nations introduce the vaccination, such as United States, Canada, Australia and Japan.[1] |

| Recent years | Today, cervical cancer is both the fourth-most common cause of cancer and the fourth-most common cause of death from cancer in women.[2] In 2012, approximately 528,000 cases of cervical cancer occurred, with 266,000 deaths.[2] This is about 8% of the total cases and total deaths from cancer.[3] About 70% of cervical cancers occur in developing countries.[2] |

Full timeline

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 BCE | Development | First description of cervical cancer by Hippocrates.[1] | |

| 1834 | Discovery | Cervical cancer is identified as a sexually transmitted disease.[4] | |

| 1842 | Discovery | Italian epidemiologist Domenico Rigoni-Stern notices that cervical carcinoma occurs only in married women.[4] | |

| 1898 | Development | Austrian gynecologist Ernst Wertheim describes the operation of radical hysterectomy including removal of the parametrium and pelvic lymph nodes. A few years later, the Wertheim-Meigs operation is introduced as a surgical procedure for the treatment of cervical cancer performed by way of an abdominal incision.[5] | |

| 1925 | Development | German gynecologist Hans Hinselmann first describes the foundation of the colposcope, a device used to examine the cervix, vagina and vulva for signs of disease.[6] | |

| 1928 | Development | Greek cytopathologist Georgios Papanikolaou develops a cervical cytology smear test (today called Pap smear) to detect cancer cells. This test will save thousands of lives and help reduce cervical cancer mortality by a wide margin.[7] | |

| 1943 | Development | The Pap test is first generalized as a procedure, enabling doctors to detect and begin treating cervical cancer before it has a chance to spread. Over the following decades, the Pap test is credited with driving down cervical cancer death rates in developed countries.[8] | |

| 1946 | Development | Aylesbury spatula, a wooden spatula with an extended tip, is introduced to scrape the cervix, collecting the sample for the Pap smear.[9] | |

| 1951 | Development | First successful in-vitro cell line, HeLa, is derived from biopsy of cervical cancer of Henrietta Lacks.[10] | United States |

| 1953 | Discovery | Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the uterine cervix is first described.[11] | |

| 1983 | Discovery | Team led by German virologists Harald Zur Hausen and Lutz Gissmann identify HPV 16 in precursor lesions of genital cancer.[1] | |

| 1984 | Discovery | Cigarette smoking is found to increase risk of cervical cancer.[12] | |

| 1985 | Discovery | Harald Zur Hausen and Lutz Gissmann demonstrate the presence of HPV DNA in cervical cancer cells. These findings create the basis for subsequent studies leading to the development of preventive vaccines.[1] | |

| 1988 | Development | The Bethesda system (TBS) is introduced as a system for reporting cervical or vaginal cytologic diagnoses. It is considered to be an important achievement in the standardization of screening results.[1] | |

| 1989 | Discovery | Villoglandular adenocarcinoma of the cervix (a rare type of cervical cancer) is first described.[13] | |

| 1989 | Development | Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), which is performed in the surgical treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, is first described.[14] | |

| 1990 | Policy | The Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act is launched, providing nationwide access to free or low-cost breast and cervical cancer screenings to underserved women.[8] | United States |

| 1996–1999 | Development | United States FDA approves two new liquid-based Pap tests. In these tests the swab is placed into a special preservative solution, instead of smearing a swab of cervical cells on a slide as in the conventional tests. Compared to the traditional method, these liquid tests provide a clearer, easier to read sample for pathologists to review under a microscope.[8] | United States |

| 1998 | Development | Researchers begin human testing of a possible vaccine to prevent cervical cancer.[15] | United States |

| 1999 | Discovery | Study shows that widespread screening reduces cases of advanced cervical cancer in older women.[16] | California, US |

| 1999 | The United States National Cancer Institute issues an alert recommending chemotherapy radiation combination for invasive cervical cancer (cancer that has spread within the cervix or pelvis). This is based on trials showing that women live longer when treated with both radiation and chemotherapy, compared to those treated with the prior standard of radiation or surgery alone.[8] | United States | |

| 1999 | Development | DNA test is approved to detect human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus that causes cervical cancer.[17] | |

| 2006 | Treatment | United States FDA approves Gardasil, a vaccine that prevents infection with the two high-risk strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) known to cause about 70 percent of cervical cancers. Gardasil is approved for girls and young women aged 9 to 26.[8] | United States |

| 2007 | Discovery | Study suggests that the act of performing a Pap smear produces an inflammatory cytokine response, which may initiate immunologic clearance of HPV, thus reducing the risk of cervical cancer.[18] | South Africa |

| 2008 | Discovery | Researchers discover that two minimally invasive techniques, laparoscopic and robotic radical hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) with radical pelvic lymphadenectomy (removal of surrounding pelvic lymph nodes) are as effective as traditional radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy in women with cervical cancer.[8] | |

| 2009 | Discovery | HPV vaccine Gardasil is found to be over 90 percent effective in preventing cervical cancer in women aged 24 to 45 who received all three vaccine doses, and who are not infected by the virus.[8] | |

| 2010 | Policy | Young women in Japan become eligible to receive cervical cancer vaccination for free. However, in 2013 the local Health Ministry withdraws the vaccine recommendation for girls due to several hundred adverse reactions to the vaccines reported.[19] | Japan |

| 2013 | Discovery | Adding targeted drug bevacizumab (Avastin) to standard chemotherapy is found to improve survival for patients with relapsed and advanced cervical cancers.[8] |

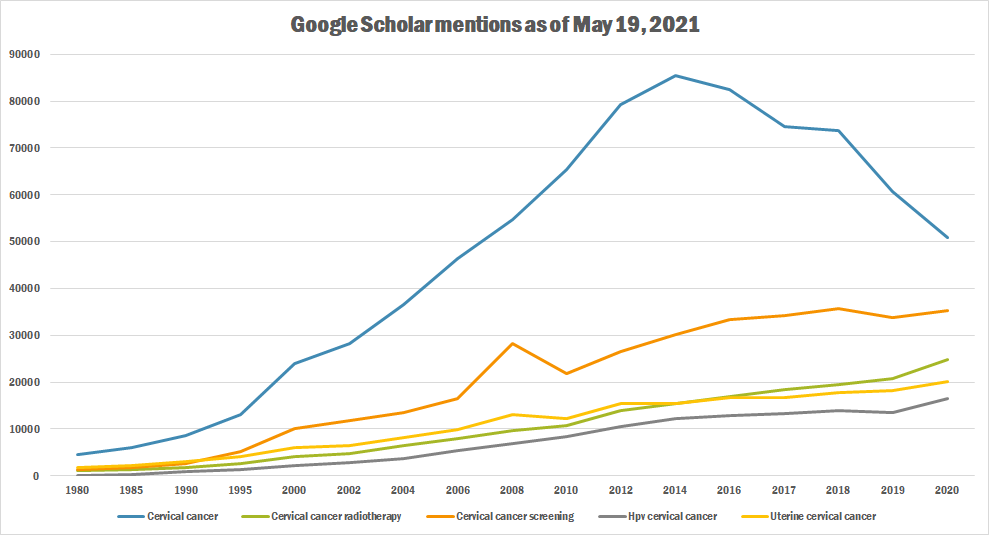

Numerical and visual data

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of May 19, 2021.

| Year | Cervical cancer | Cervical cancer radiotherapy | Cervical cancer screening | Hpv cervical cancer | Uterine cervical cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 4,470 | 1,100 | 1,230 | 22 | 1,830 |

| 1985 | 6,050 | 1,380 | 1,700 | 213 | 2,230 |

| 1990 | 8,570 | 1,830 | 2,710 | 811 | 3,130 |

| 1995 | 13,100 | 2,600 | 5,070 | 1,410 | 4,000 |

| 2000 | 24,000 | 4,120 | 9,990 | 2,270 | 6,100 |

| 2002 | 28,300 | 4,830 | 11,700 | 2,800 | 6,510 |

| 2004 | 36,500 | 6,450 | 13,400 | 3,730 | 8,180 |

| 2006 | 46,300 | 7,950 | 16,500 | 5,280 | 9,810 |

| 2008 | 54,700 | 9,560 | 28,200 | 6,910 | 13,100 |

| 2010 | 65,300 | 10,700 | 21,900 | 8,280 | 12,300 |

| 2012 | 79,300 | 14,000 | 26,600 | 10,600 | 15,400 |

| 2014 | 85,400 | 15,500 | 30,200 | 12,200 | 15,500 |

| 2016 | 82,400 | 17,000 | 33,300 | 12,800 | 16,800 |

| 2017 | 74,500 | 18,400 | 34,300 | 13,200 | 16,800 |

| 2018 | 73,700 | 19,500 | 35,700 | 13,900 | 17,700 |

| 2019 | 60,800 | 20,700 | 33,700 | 13,400 | 18,200 |

| 2020 | 50,900 | 24,800 | 35,200 | 16,400 | 20,200 |

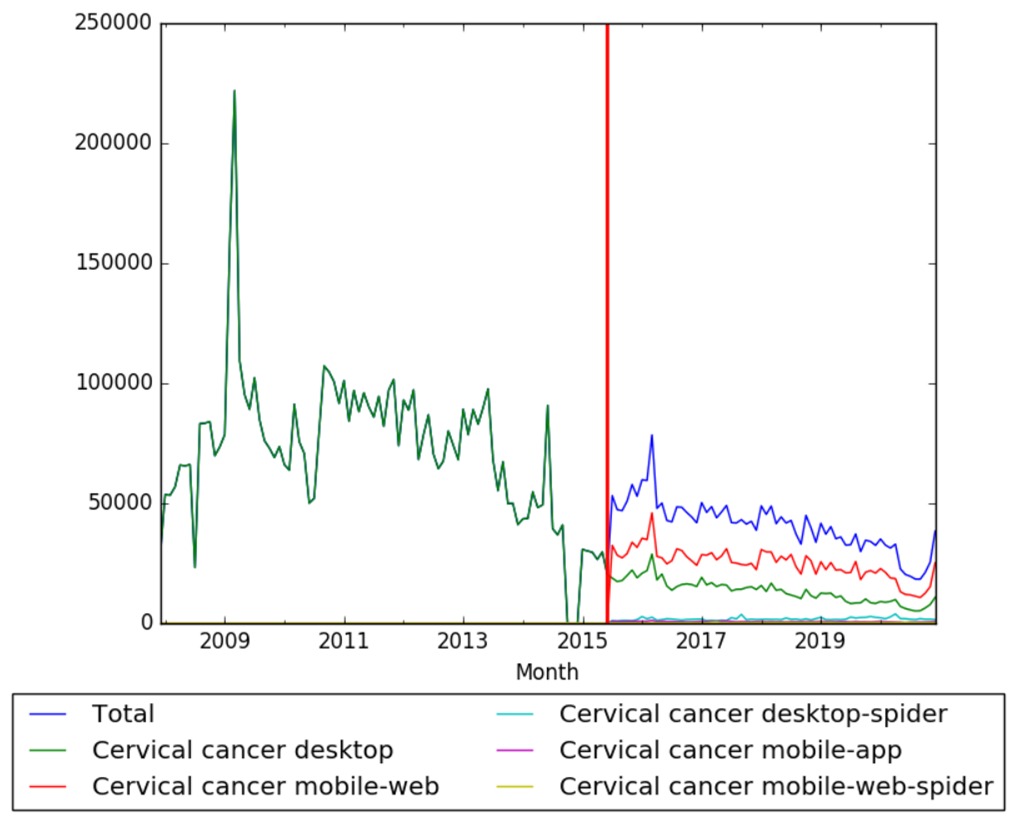

Wikipedia Views

See also

- Timeline of lung cancer

- Timeline of brain cancer

- Timeline of kidney cancer

- Timeline of colorectal cancer

- Timeline of pancreatic cancer

- Timeline of liver cancer

- Timeline of bladder cancer

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Cervical cancer: From Hippocrates through Rigoni-Stern to zur Hausen" (PDF). Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.12. ISBN 9283204298.

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 9283204298.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Al-Daraji,, Wael I; Smith, John HF (2009). "Infection and Cervical Neoplasia: Facts and Fiction". Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2: 48–64. PMC 2491386

. PMID 18830380.

. PMID 18830380.

- ↑ "Radical Hysterectomy with Pelvic Lymphadenectomy: Indications, Technique, and Complications". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2010: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2010/587610.

- ↑ "What is a colposcope?". Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Bower, Mark; Waxman, Jonathan. Lecture Notes: Oncology.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 "Cervical Cancer". Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Shariff, Shameem; Kaler, Amrit Kaur. Principles & Interpretation of Laboratory Practices in Surgical Pathology.

- ↑ "Study of Cervical Cancer That Killed 'Medical Miracles' Woman Henrietta Lacks Published for First Time". Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ "Cervical squamous and glandular intraepithelial neoplasia: Identification and current management approaches". Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Smoking increases risk of cervical cancer". Gadsden Times.

- ↑ Dilley, Sarah; Newbill, Colin; Pejovic, Tanja; Munroc, Elizabeth (2015). "Two cases of endocervical villoglandular adenocarcinoma: Support for conservative management". Gynecol Oncol Rep. 12: 34–6. PMC 4442649

. PMID 26076156. doi:10.1016/j.gore.2015.02.004.

. PMID 26076156. doi:10.1016/j.gore.2015.02.004.

- ↑ Jiang, Yan-Ming; Chen, Chang-Xian; Li, Li (2016). "Meta-analysis of cold-knife conization versus loop electrosurgical excision procedure for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia". Onco Targets Ther. 9: 3907–15. PMC 4934869

. PMID 27418835. doi:10.2147/OTT.S108832.

. PMID 27418835. doi:10.2147/OTT.S108832.

- ↑ "Cervical cancer vaccine". Ellensburg Daily Record.

- ↑ "Decreased Incidence of Cervical Cancer in Medicare‐Eligible California Women". Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Human Papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou Screening Tests for Cervical Cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 357: 1579–1588. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa071430.

- ↑ Passmore, Jo-Ann S; Williamson, Anna-Lise; Hoffman, Margaret; Shapiro, Samual; Morroni, Chelsea (2007). "Papanicolaou smears and cervical inflammatory cytokine responses". Journal of Inflammation. 4: 8. PMC 1868022

. PMID 17456234. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-4-8.

. PMID 17456234. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-4-8.

- ↑ "Japan's Health Ministry Withdraws Cervical Cancer Vaccine Recommendation". Retrieved 19 September 2016.