Timeline of tobacco smoking and disease

This is a timeline of smoking and disease, attempting to describe events related to the effect of tobacco on health. In order to provide context, the timeline includes many events related to tobacco production, introduction, and policies regulating its use.

Sample questions

The following are some interesting questions that can be answered by reading this timeline:

- What types of tobacco exposure are described?

- Sort the full timeline by "Inhalation type".

- You will see a category consisting in mainstream smoke, second, and third-hand smoke.

- What are some of the several diseases and health effects related to tobacco exposure?

- Look for the different values on the column under title "Health impact (when applicable)".

- You will see a notable number of cancers (especially lung cancer), as well as other diseases and behavioral conditions.

- What are some events describing research related to tobacco smoking?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the rows with the value "Research".

- You will mostly see medical research on the effect of tobacco smoking on health.

- What are some events describing tobacco consumption?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the rows with the value "Tobacco consumption".

- You will mostly see a bunch of historical records of tobacco consumption in early times, as well as some recent notable trends.

- What are some events describing the introduction of tobacco in some countries?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the rows with the value "Tobacco introduction".

- You will mostly see the introduction of tobacco from the Americas into European colonial powers.

- What are some events related to the production of tobacco?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the rows with the value "Tobacco industry".

- What are some events illustrating governmental implementations related to tobacco use around the world?

- Sort the full timeline by "Event type" and look for the rows with the value "policy".

- You will see a variety of regulations, mainly smoking bans, with an increasing number of countries hoping to eliminate tobacco use.

- Other events are described under the following types: "Campaign", "Cigarette advertising", "Concept development", "Public opinion", "Publication", and "Statistics".

Big picture

| Time period | Development summary | More details |

|---|---|---|

| Before 1880 | Pre-cigarette era | Tobacco is grown as early as in 6000 BC in the Americas. The European colonization of the Americas introduces tobacco in the Old continent. Policies against smoking already appear in the sixteenth century. Addiction is an early found health consequence. By the 18th and 19th century, smoking bans and prohibitions become rare, and trade in tobacco becomes an important source of revenue for monarchs and leaders.[1] |

| 1880 onwards | Cigarette era | Mass production of cigarettes begins after James Albert Bonsack invention of his cigarette rolling machine, which would allow production and consumption to grow tremendously until the health revelations of the late 20th century. |

| 1950s onwards | Tobacco and disease | Since the 1950s, increased evidence is found linking smoking to cancer, especially lung cancer. Research on health effects of passive smoking also increases. |

Summary by decade

| Time period | Development summary |

|---|---|

| 1920s | A rise of lung cancer prompts epidemiologic research on its causes in the United States and Europe. Initial studies find an association between lung cancer and tobacco smoking.[2] |

| 1930s | Scholars and activists in the United States become aware of increasing cancer death rates.[2] Researchers begin to investigate the relationship using the methods of case-control epidemiology. |

| 1940s | Cigarettes start being recognized as the cause of the emerging lung cancer epidemic, a very rare disease in the past.[3] |

| 1950s | Epidemiologic evidence on lung cancer and smoking becomes abundant and coherent. By the late decade, the amassing evidence that smoking causes lung cancer calls for public health action.[2][4] |

| 1960s | Surveys of physicians continue to show decreasing prevalence of smoking and acceptance of the hazards of cigarette smoking.[2] |

| 1970s | Researchers find solid evidence that tobacco smoking is addictive, and this behavior is found to resemble other drugs.[2] |

| 1980s | Surveys in the United States suggest that only 5–10% of physicians smoke.[2] An increasing number of lawsuits are filed against the tobacco industry because of the harmful effects of its products. Smoking becomes politically incorrect, with more public places forbidding smoking.[4] The tobacco industry starts marketing heavily in areas outside the U.S., especially developing countries in Asia.[4] |

| 1990s | An increasing majority of the public in Western Countries acknowledge that cigarette smoking is harmful to health.[2] |

| 2000s | Smoking rates decline in multiple countries around the world.[5][6][7] |

Full timeline

| Year | Health impact (when applicable) | Tobacco exposure type (when applicable) | Event type | Details | Country/region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6000 BC | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | Tobacco is recorded to be grown in America since about this time.[8] | Americas | |

| 1400 BC–1000 BC | Tobacco industry | Tobacco is cultivated in Mexico.[9] | Mexico | ||

| c.1 BCE | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | It is believed that use of tobacco begins in the Americas, including smoking (via a number of variations) and in enemas.[1] | ||

| c.1 CE | Tobacco consumption | Tobacco is found "nearly everywhere" in the Americas.[10][1] | Americas | ||

| 1492 (October 15) | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | Christopher Columbus discovers smoking.[1] He is offered dried tobacco leaves as a gift from the American Indians that he encountered.[4] | The Bahamas | |

| 1518 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | Spanish conquistador Juan de Grijalva lands in Yucatan, and observes cigarette smoking by natives.[1] | ||

| 1531 | Tobacco industry | Cultivation of tobacco begins in Europe.[1] | Europe | ||

| 1535 | Tobacco consumption | French explorer Jacques Cartier encounters natives on the island of Montreal who use tobacco.[1] | Canada | ||

| 1548 | Tobacco industry | The Portuguese cultivate tobacco in Brazil for commercial export.[1] | Brazil | ||

| 1556 | Tobacco introduction | Tobacco is introduced in France.[1] | France | ||

| 1558 | Tobacco introduction | Tobacco is introduced in Portugal.[1] | Portugal | ||

| 1559 | Tobacco introduction | Tobacco is introduced in Spain.[1] | Spain | ||

| 1560 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | Jean Nicot, the French ambassador to Lisbon, is given some seeds by Portuguese sailors returning from the New World. Nicot grows them and sends the leaves to Queen Mother Catherine de' Medici, who likes to sniff the powder made from them.[8] | Europe | |

| 1563 | Mainstream smoke | Research | Swiss doctor Conrad Gesner reports that chewing or smoking a tobacco leaf "has a wonderful power of producing a kind of peaceful drunkenness".[11] | Switzerland | |

| 1564 | Tobacco introduction | Tobacco is introduced in England.[1] | United Kingdom | ||

| 1571 | Research | Spanish doctor Nicolas Monardes writes a book about the history of medicinal plants of the new world. In this he claims that tobacco could cure 36 health problems.[4] | Spain | ||

| 1575 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The Roman Catholic Church forbids the use of tobacco in any church in Mexico. This is one of the first documented smoking bans in history.[8][1] | Mexico | |

| 1588 | Nose cancer | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | A Virginian named Thomas Harriet promotes smoking tobacco as a viable way to get one's daily dose of it. Harriet later dies of nose cancer, as it is popular then to breathe the smoke out through the nose.[4] | United States |

| 1590 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Pope Urban VII moves against smoking in church buildings.[12] | Italy | |

| 1604 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | King James VI and I publishes an anti-smoking treatise, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, that would susequently have the effect of raising taxes on tobacco. | ||

| 1610 | Addiction | Mainstream smoke | Research | Sir Francis Bacon notes that trying to quit the habit of smoking is really hard.[4] | United Kingdom |

| 1612 | Policy | Use and cultivation of tobacco is borbidden in China.[1] | China | ||

| 1617 | Policy | Mughal emperor Jahangir prohibits the use of tobacco.[13] | Mongolia | ||

| 1620 | Policy | Japan outlaws tobacco.[8] | Japan | ||

| 1624 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Pope Urban VIII issues a worldwide smoking ban, on the logic that tobacco use prompts sneezing, which too closely resembles sexual ecstasy. The pope also threatens excommunication for those who smoke or take snuff in holy places.[14] | ||

| 1627 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Russia bans tobacco. The ban would last 70 years.[15] | Russia | |

| 1632 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | 12 years after the English ship Mayflower arrives on Plymouth Rock, it becomes illegal to smoke publicly in Massachusetts. The ban has more to do with the moral beliefs of the day, than health concerns about smoking tobacco.[4] | United States | |

| 1632 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The first anti-smoking law in the United States is passed, when Massachusetts bans smoking in public places.[8] | United States | |

| 1633 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The Ottoman Sultan Murad IV prohibits smoking in his empire and has smokers executed.[14] | Turkey | |

| 1634 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Tsar Michael of Russia bans smoking, promising even first-time offenders whippings, floggings, a slit nose, and an exile to Siberia.[14] | ||

| 1634 | Intoxication | Mainstream smoke, second-hand smoke | Policy | The Greek Church bans the use of tobacco, claiming that tobacco smoke produces intoxication.[1] | Greece |

| 1638 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | China makes the use and supply of tobacco a crime punishable by decapitation.[8] | China | |

| 1640 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Bhutan unifier Ngawang Namgyal outlaws the use of tobacco in government buildings.[1] | Bhutan | |

| 1647 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | In Connecticut, people are only allowed to smoke once a day and public smoking is prohibited.[1] | United States | |

| 1657 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking is banned in Switzerland.[1] | Switzerland | |

| 1674 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smokers in Russia are deemed criminals subject to the death penalty. Two years later, the smoking ban would be lifted.[14] | Russia | |

| 1719 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking is banned in most French provinces.[1] | France | |

| 1723 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking is banned in Berlin.[16] | Germany | |

| 1760 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | French–American tobacconist Pierre Abraham Lorillard establishes the Lorillard Tobacco Company in New York City to process tobacco, cigars, and snuff.[4] | United States | |

| 1761 | Nose cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | John Hill in England performs an early clinical study of tobacco effects, warning snuff users they are vulnerable to cancers of the nose.[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1795 | Lip cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | German physician Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring reports on cancers of the lip in pipe smokers.[1] | Germany |

| 1798 | Drunkeness | Mainstream smoke, chewing | Research | American physician Benjamin Rush claims that smoking or chewing tobacco leads to drunkenness.[1] | United States |

| 1826 | Poisoning | Research | The pure form of nicotine is discovered. Soon after, scientists conclude that nicotine is a dangerous poison.[4] | ||

| 1836 | Poisoning | Research | New Englander Samuel Green states that tobacco is an insecticide, a poison, and can kill a man.[4] | United States | |

| 1830s | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | Cigarettes start to appear in this decade.[8] | ||

| 1847 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | Phillip Morris is established, selling hand rolled Turkish cigarettes.[4] | United States | |

| 1876 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The Old Government Building in Wellington, New Zealand, becomes the first building in the world to ban smoking. The ban is motivated by the threat of fire, as it is the second largest wooden building in the world.[17] | New Zealand | |

| 1877 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Rutherford Hayes becomes the first United States president to ban smoking in the White House.[8] | United States | |

| 1880 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | James Albert Bonsack in the United States invents what is considered to be the first practical cigarette-making machine. This invention allows for a massive production of cigarettes.[18][19] | United States | |

| 1889 | Research | Langley and Dickinson publish studies on the effects of nicotine on the ganglia, establishing the ability of nicotine to block the neurons in the superior cervical ganglion.[20] | |||

| 1890 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | New Brunswick in Canada bans underage smoking. This would be followed by Ontario and Nova Scotia in 1892.[21] | Canada | |

| 1890 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | 26 American states ban tobacco sales to minors. Further restrictions are imposed over the next decade.[21] | United States | |

| 1891 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Grand Ayatollah Mirza Mahdi al-Shirazi issues a fatwa banning Shiites from using or trading tobacco.[14] | Iran | |

| 1895 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The sale of cigarettes is banned in North Dakota. Over the next twenty-six years, fourteen other statehouses, propelled by the national temperance movement, would follow suit.[14] | United States | |

| 1908 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | New York City passes the Sullivan Act, which bans women from smoking in public.[8] | United States | |

| 1911 | Tobacco industry | For the first time in over 250 years, tobacco growing is allowed in England.[1] | United Kingdom | ||

| 1912 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | American Dr. Isaac Adler is the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking.[22] | United States |

| 1913 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | American businessman R. J. Reynolds begins to market a cigarette brand called Camel.[4] | United States | |

| 1914 | Mainstream smoke | Publication | American industrialist Henry Ford publishes a pamphlet called “The Case Against the Little White Slaver,” with a foreword by Thomas Edison, who said he didn’t employ smokers"[8] | United States | |

| 1914–1918 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | The use of cigarette explodes during World War I, where cigarettes are called the "soldier's smoke".[4] | ||

| 1925–1935 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | Smoking rates among female teenagers triple in this period, after the American Tobacco Company began to market its cigarette to women, gaining 38% of the market.[4] | United States | |

| 1929 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | American business consultant Edward Bernays proposes an increase of market share for Lucky Strikes by getting women to smoke. Bernays hires models, debutantes and feminists to march down Fifth Avenue while smoking, in a “Torch of Freedom” march.[8] | United States | |

| 1930 | Cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Researchers in Germany find a statistical correlation between cancer and smoking.[1] | Germany |

| 1936 | Mainstream smoke | Research | Bogen publishes study on the irritant factors in cigarette smoke, and classifies formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein (propenal) as "irritant factors" in cigarette smoke, rating formaldehyde as a major contributor to cigarette smoke irritation.[23] | ||

| 1939 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Franz Hermann in Cologne publishes an early study correlating tobacco smoke with lung cancer.[3] | Germany |

| 1939 | Mainstream smoke | Research | Ribeiro reports the presence of acrolein (propenal) in tobacco smoke.[23] | ||

| 1939–1945 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | During World War II cigarette sales climb to an all time high. Cigarettes are included in a soldier's C-Rations (like food). Tobacco companies send millions of cigarettes to the soldiers for free, and when these soldiers came home, the companies gain a steady stream of loyal customers.[4] | ||

| 1941 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Dr. Michael DeBakey cites a correlation between the increased sale of tobacco and the increasing prevalence of lung cancer.[1] | |

| 1942 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Adolf Hitler directs an aggressive antismoking campaign, including heavy taxes and bans on smoking in many public places.[14] | Germany | |

| 1942 | Addiction | Mainstream smoke | Research | British researcher L.M. Johnston finds that tobacco addiction is not about the act of smoking itself, but the craving for nicotine.[24] | |

| 1948 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Lung cancer is reported to have grown 5 times faster than other cancers since 1938.[1] | |

| 1950 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Five separate epidemiological studies are published in this year, all confirming that smokers of cigarettes are far more likely to contract lung cancer than non-smokers.[3] | United States |

| 1952 | Health impact of asbestos | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | P. Lorillard markets its Kent brand with the "micronite" filter, which contains asbestos. The brand would be later discontinued.[4] | |

| 1953 | Cancer | Third-hand smoke | Research | Dr. Ernst L. Wynders finds that putting cigarette tar on the backs of mice causes tumors.[4] | |

| 1954 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Doll and Hill conclude that smokers of 35 or more cigarettes per day increase their odds of dying from lung cancer by a factor of 40.[3] | |

| 1957 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Publication | The British Research Council states that "... a major part of the increase [in lung cancer] is associated with tobacco smoking, particularly in the form of cigarettes" and that "the relationship is one of direct cause and effect."[1] | United Kingdom |

| 1958 | Cancer | Mainstream smoke | Public opinion | 44 percent of people in the United States already believe smoking causes cancer.[25] | United States |

| 1958 | Lung disease, heart disease | Mainstream smoke | Research | A number of medical associations warns that tobacco use is linked with both lung and heart disease.[25] | United States |

| 1959 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Documents show that the industry is well aware of the presence of a radioactive substance in tobacco at this time. Furthermore, the industry is not only cognizant of the potential "cancerous growth" in the lungs of regular smokers but also conducts quantitative radiobiological calculations to estimate the long-term (25 years) lung radiation absorption dose (rad) of ionizing alpha particles emitted from the cigarette smoke.[26] | |

| 1960 | Mainstream smoke | Research | As of date, only one-third of all doctors in the United States believe that the case against cigarettes has been established.[3] | United States | |

| 1962 | Heart cancer, lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A study states a conclusive link between smoking and heart and lung cancer in men. The report also states the same link is likely true for women, although women smoke at lower rates and therefore not enough data is available.[25] | |

| 1964 | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Almost one-half of U.S. adults are cigarette smokers at this time, and smoking is ubiquitous in many public places, including restaurants, theaters, and airplane cabins.[2] | United States | |

| 1964 | Bladder cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A report by the Surgeon General of the United States (USDHEW 1964) notes a relationship between smoking and bladder cancer.[27] | United States |

| 1965 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Television cigarette ads are removed from the air in Great Britain.[4] | United Kingdom | |

| 1966 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Health warnings on cigarette packs begin to appear.[4] | ||

| 1968 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | The Surgeon General of the United States concludes that smoking causes lung cancer in women.[27] | |

| 1968 | Influenza | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research of 1,900 male cadets after the 1968 Hong Kong A2 influenza epidemic at a South Carolina military academy, compares thee groups: nonsmokers, heavy smokers, and light smokers. Compared with nonsmokers, heavy smokers (more than 20 cigarettes per day) had 21% more illnesses and 20% more bed rest, light smokers (20 cigarettes or fewer per day) had 10% more illnesses and 7% more bed rest.[28]" | United States |

| 1968 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco industry | Bravo is marketed as a non-tobacco cigarette brand. Made primarily of lettuce, it fails spectacularly.[4] | ||

| 1970 | Second-hand smoke | Concept development | The term "passive smoking" is first used in the title of a scientific paper.[29] | ||

| 1971 (January 1) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The last cigarette television advertisement is aired in the United States.[8] | United States | |

| 1972 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Surgeon General of the United States report (USDHEW 1972) notes that epidemiologic evidence demonstrates a significant association between cigarette smoking and cancer of the pancreas.[27] | United States |

| 1973 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Arizona becomes the first state to restrict smoking in some public spaces.[2] | United States | |

| 1973 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board orders domestic airlines to provide separate seating for smokers and nonsmokers.[2] | United States | |

| 1974 | Second-hand smoke | Concept development | The term "environmental tobacco smoke" can be traced back to an industry-sponsored meeting held in Bermuda.[29] | Bermuda | |

| 1974 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission rules that smoking be restricted to the rear 20% of seats in interstate buses.[2] | United States | |

| 1974 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Connecticut enacts the first statute to restrict smoking in restaurants.[2] | United States | |

| 1975 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking restrictions start being put in place in the United States, with the first in Minnesota and carrying on with various local and state governments legislating smoke-free or clean indoor air laws. "In 1975 the U.S. state of Minnesota enacted the Minnesota Clean Indoor Air Act, making it the first state to restrict smoking in most public spaces. At first restaurants were required to have "No Smoking" sections, and bars were exempt from the Act" | United States | |

| 1975 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Italy bans smoking on public transit vehicles (except for smokers' rail carriages) and in some public buildings (hospitals, cinemas, theatres, museums, universities and libraries).[30] | Italy | |

| 1975 | Tooth loss | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research concludes that tooth loss is twice higher in smokers than in non-smokers[31] | |

| 1977 | Mainstream smoke | Caimpaign | The first national Great American Smokeout takes place. The event challenges people to quit smoking on that day, or use the day to make a plan to quit.[4] | United States | |

| 1977 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Berkeley, California, becomes the first city to pass an ordinance limiting smoking in restaurants.[2] | United States | |

| 1979 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A report by the Surgeon General of the United States (USDHEW 1979) indicates that a dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer has been demonstrated.[27] | United States |

| 1979 | Influenza | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Surveillance of a current influenza outbreak at a military base for women in Israel reveals that influenza symptoms developed in 60.0% of the current smokers vs. 41.6% of the nonsmokers.[32] | Israel |

| 1979 | Mainstream smoke | Pulbication | In light to the increasing number of women who are taking up the smoking habit, the Surgeon General of the United States reports on the Health Consequences of Smoking for Women.[4] | United States | |

| 1980 | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Smoking in the United States peaks to 631.5 billion cigarettes sold in the year.[8] | United States | |

| 1980 | Bladder cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | The United States Department of Health and Human Services report (USDHHS 1980) notes a dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and the risk of bladder cancer.[27] | United States |

| 1980–1981 | Lung disease | Second-hand smoke | Research | Scientific journals publish epidemiologic research from Greece, Japan, and the United States finding that those who breathe “environmental tobacco smoke” suffer from decreased lung function.[2] | Greece, Japan, United States |

| 1982 | Kidney cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Report by the Surgeon General of the United States concludes that cigarette smoking is a contributory factor in the development of kidney cancer.[27] | United States |

| 1982 | Influenza | Mainstream smoke, second-hand smoke | Research | Research concludes that smoking may substantially contribute to the growth of influenza epidemics affecting the entire population.[33] | |

| 1982 | Esophageal cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Report by the Surgeon General of the United States concludes that smoking is a major cause of esophageal cancer.[27] | United States |

| 1982 | Lung cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | The Surgeon General of the United States reports that second-hand smoke may cause lung cancer. This causes smoking in public areas to be soon restricted, especially at the workplace.[4] | |

| 1985 | Lung cancer | Mainstram smoke | Research | Lung cancer becomes the first killer of women, beating out breast cancer.[4] | |

| 1986 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstram smoke | Research | The International Agency for Research on Cancer concludes that smoking causes cancer of the pancreas.[27] | |

| 1986 | Lung cancer, respiratory symptoms | Second-hand smoke | Research | Two major scientific reviews are released in the United States, the Surgeon General's report, The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking, and the National Academy of Science's report, Environmental Tobacco Smoke: Measuring Exposures and Assessing Health Effects, both concluding that secondhand smoke could cause lung cancer in healthy adult nonsmokers and respiratory symptoms in children.[2] | United States |

| 1986 | Lung cancer, oral cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, hypopharyngeal cancer, Laryngeal cancer, esophageal cancer, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, pancreatic cancer | Mainstram smoke | Research | The International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph on tobacco smoking considers the following cancers to be causally related to tobacco smoking: Cancers of the lung, upper aerodigestive tract (oral cancer and cancer of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and oesophagus), urinary bladder and renal pelvis and pancreas.[34] | |

| 1987 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The United States Congress bans smoking on all domestic flights lasting less than 2 hours.[4] | United States | |

| 1988 | Addiction | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research by the Surgeon General of the United States concludes that cigarettes are addicting, similar to heroin and cocaine, and that nicotine is the primary agent of addiction.[2] | United States |

| 1989 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Report by the Surgeon General of the United States estimates that 29 percent of pancreatic cancer deaths in men and 34 percent in women could be attributed to smoking.[27] | |

| 1989 | Inflammatory bowel disease | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research indicates that smoking increases the risk of symptoms associated with inflammatory bowel disease.[35] | |

| 1990 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking is banned on all domestic flights across the United States, except to Alaska and Hawaii.[4] | United States | |

| 1990 | Bladder cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Report by the United States Department of Health and Human Services concludes that smoking causes bladder cancer.[27] | |

| 1990 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Report by the United States Department of Health and Human Services concludes that smoking cessation reduces the risk of lung cancer compared with continued smoking.[27] | |

| 1990 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Investigations of K-ras mutations in pancreatic cancer show that the probability of mutation are significantly higher among smokers compared with nonsmokers in several studies.[27] | |

| 1992 | Second-hand smoke | Statistics | A review estimates that secondhand smoke exposure is responsible for 35,000 to 40,000 deaths per year in the United States in the early 1980s.[36] | United States | |

| 1993 | Influenza | Mainstream smoke | Research | A study of community-dwelling people 60–90 years of age, finds that 23% of smokers have clinical influenza as compared with 6% of non-smokers.[37] | |

| 1994 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | A number of academic medical centers in the United States adopt policies barring their faculty and staff from accepting tobacco industry support.[2] | United States | |

| 1995 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | California becomes the first U.S. state to ban smoking in enclosed public spaces.[25] | United States | |

| 1996 | Impaired vasolidation | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with impaired vasodilation among adult nonsmokers.[38] | |

| 1997 | Sudden infant death syndrome | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).[39] | |

| 1997 | Behavioral effects | Mainstream smoke | Research | Medical researchers find that smoking is a predictor of divorce.[40] | |

| 1998 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research finds that nicotine activates the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway in lung cancer cells.[41] | |

| 1998 | Behavioral effects | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research finds that smokers have a 53% greater chance of divorce than nonsmokers.[42] | |

| 1999 | Stress | Mainstream smoke | Research | American Psychologist states: "Smokers often report that cigarettes help relieve feelings of stress. However, the stress levels of adult smokers are slightly higher than those of nonsmokers, adolescent smokers report increasing levels of stress as they develop regular patterns of smoking, and smoking cessation leads to reduced stress. Far from acting as an aid for mood control, nicotine dependency seems to exacerbate stress. This is confirmed in the daily mood patterns described by smokers, with normal moods during smoking and worsening moods between cigarettes. Thus, the apparent relaxant effect of smoking only reflects the reversal of the tension and irritability that develop during nicotine depletion. Dependent smokers need nicotine to remain feeling normal."[43] | |

| 1999 | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research indicates that second-hand smoke exposure also affects platelet function, vascular endothelium, and myocardial exercise tolerance at levels commonly found in the workplace.[44] | ||

| 2000 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research associates being a current smoker with a fourfold increase in the risk of invasive disease caused by the pathogenic bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae.[45] | |

| 2000 | Mainstream smoke | Tobacco consumption | About 4.2 million hectares of tobacco were under cultivation worldwide in this year, yielding over seven million tons of tobacco.[46] | ||

| 2001 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A report by the Surgeon General of the United States on women and smoking concludes that “About 90 percent of all lung cancer deaths among U.S. women smokers are attributable to smoking”.[27] | United States |

| 2001 | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research concludes that exposure to tobacco smoke for 30 minutes significantly reduces coronary flow velocity reserve in healthy nonsmokers.[47] | ||

| 2001 | Squamous cell skin cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A study conducted in the Netherlands shows that the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is increased by tobacco smoking.[48] | Netherlands |

| 2002 | Death | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Research in Canada shows that about 17% of deaths are due to smoking (20% in males and 12% in females).[49] | Canada |

| 2002 | Cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | A study issued by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization concludes that non-smokers are exposed to the same carcinogens on account of tobacco smoke as active smokers.[50] | |

| 2002 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | The International Agency for Research on Cancer again concludes that smoking causes cancer of the pancreas and that the risk for pancreatic cancer increases with the duration of smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked daily; the risk remains high after allowing for potential confounding factors such as alcohol consumption; and the risk decreases with increasing time since quitting smoking.[27] | |

| 2002 | Kaposi's sarcoma, HIV/AIDS | Mainstream smoke | Research | A study shows that smoking increases the risk of Kaposi's sarcoma in people without HIV infection.[51] | |

| 2003 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | India introduces a law banning smoking in public places like restaurants, public transport or schools. The same law also prohibits advertising cigarettes or other tobacco products.[52] | India | |

| 2003 (December 3) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | New Zealand passes legislation to progressively implement a smoking ban in schools, school grounds, and workplaces by December 2004.[53] | New Zealand | |

| 2003 | Follicular lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research estimates in a case-control study including 1,319 patients that cigarette smoking has a significant impact on the risk of follicular lymphoma but not on the risk of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes.[48] | |

| 2003 | Second-hand smoke | Concept development | As of year, "secondhand smoke" is the term most used to refer to other people's smoke in the English-language media.[29] | ||

| 2004 | Asthma, allergies, and other conditions | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with worsening of asthma, allergies, and other conditions.[54] | |

| 2004 | Endometriosis | Mainstream smoke | Research | Some evidence is found for decreased rates of endometriosis in infertile smoking women.[55] | |

| 2004 | Bladder cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research observes in a U.S. population that there is a positive association between the use of tobacco and bladder cancer and that gender does not modify this association.[48] | United States |

| 2004 (March 29) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The Republic of Ireland implements a nationwide ban on smoking in all workplaces.[56] | Ireland | |

| 2004 (June 1) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Norway implements a nationwide ban on indoor smoking, becoming the second country to implement a nationwide ban on all indoor smoking, following Ireland by 3 months.[57] | Norway | |

| 2004 | Breast cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | The International Agency for Research on Cancer concludes that there is "no support for a causal relation between involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke and breast cancer in never-smokers.[58] | |

| 2004 | Cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | The International Agency for Research on Cancer concludes that "Involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) is carcinogenic to humans.[58] | |

| 2004 | Third-hand smoke | Research | A study measures the levels of nicotine in dust in the homes of three different groups of families. Homes where parents smoke with children present in the home have the highest levels of nicotine found in dust in all rooms of the house, including the rooms of infants and children. Homes where parents attempt to limit exposure of cigarette smoke to their children have lower levels of nicotine found in dust. Homes that have not been smoked in do not contain any traces of nicotine.[59] | ||

| 2004 | Policy | Bhutan becomes the first country to completely outlaw the cultivation, harvesting, production, and sale of tobacco products.[60] | Bhutan | ||

| 2004 | Irritability, jitteriness, dry mouth, rapid heart beat | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research indicates that most smokers, when denied access to nicotine, exhibit withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, jitteriness, dry mouth, and rapid heart beat.[61] | |

| 2004 | Mainstream smoke, second-hand smoke | Research | A study shows bars and restaurants in New Jersey have more than nine times the levels of indoor air pollution of New York City, which has already enacted its smoking ban.[62] | United States | |

| 2004 | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Smoking rates decline to about 21% of Americans by this year.[8] | United States | |

| 2005 | Cardiovascular disease | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research concludes that secondhand tobacco smoke exposure has immediate and substantial effects on blood and blood vessels in a way that increases the risk of a heart attack, particularly in people already at risk.[63] | |

| 2005 | Erectile dysfunction | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research shows that smoking is a key cause of erectile dysfunction (ED).[64] | |

| 2005 | Intoxication | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research shows that inhaled sidestream smoke is about four times more toxic than mainstream smoke.[65][66] | |

| 2005 | Breast cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | The California Environmental Protection Agency concludes that passive smoking increases the risk of breast cancer in younger, primarily premenopausal females by 70%.[67] | |

| 2005 | Pulmonary emphysema | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research shows that pulmonary emphysema can be induced in rats through acute exposure to sidestream tobacco smoke (30 cigarettes per day) over a period of 45 days.[68] | |

| 2006 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Scottish politician Andy Kerr introduces in Scotland a ban on smoking in public areas.[69] | United Kingdom (Scotland) | |

| 2006 | Sudden infant death syndrome | Second-hand smoke | Research | A report by the Surgeon General of the United States concludes: "The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between exposure to secondhand smoke and sudden infant death syndrome."[70] | United States |

| 2006 | Asthma | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research finds positive association between household secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and the relative risk of developing asthma during childhood.[71][72] | |

| 2006 | Sudden infant death syndrome | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoking with 430 sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) deaths in the United States annually.[73] | United States |

| 2007 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Smoking is banned in all public places in the whole of the United Kingdom.[74] | United Kingdom | |

| 2007 | Mainstream smoke | Cigarette advertising | As of year, only one Formula One team, Scuderia Ferrari, receives sponsorship from a tobacco company; Marlboro.[75][76][77] | ||

| 2007 | Mainstream smoke | Public opinion | A poll by Gallup finds that 54% of Americans favour completely smoke-free restaurants, 34% favour completely smoke-free hotel rooms, and 29% favour completely smoke-free bars.[78] | United States | |

| 2007 | Low birth weight | Mainstream smoke, second-hand smoke | Research | Research suggests that environmental tobacco smoke exposure and maternal smoking during pregnancy cause lower infant birth weights.[79] | |

| 2007 | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research suggests that smoking increases levels of liver enzymes that break down drugs and toxins. That means that drugs cleared by these enzymes are cleared more quickly in smokers, which may result in the drugs not working. Specifically, levels of CYP1A2 and CYP2A6 are induced.[80] | ||

| 2008 (December) | Mainstream smoke | Public opinion | Gallup poll, of over 26,500 Europeans, finds that "a majority of EU citizens support smoking bans in public places, such as offices, restaurants and bars. The poll further finds that "support for workplace smoking restrictions is slightly higher than support for such restrictions in restaurants (84% vs. 79%). Two-thirds support smoke-free bars, pubs and clubs.[81] | Europe | |

| 2008 | Neurobehavioral effects | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research identifies neurobehavioral effects of second-hand smoking.[82] | |

| 2008 | Endometrial cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A meta-analysis of 34 studies notes that endometrial cancer, which is considered as one of the most common female genital tumors, is negatively associated with ever smoking.[83] | |

| 2008 (September) | Inflammatory bowel disease | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research suggests that prenatal and childhood passive smoke exposure does not appear to increase the risk of inflammatory bowel disease.[84] | |

| 2008 (October) | Tooth decay | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research finds an increase in tooth decay (as well as related salivary biomarkers) associated with passive smoking in children.[85] | |

| 2008 (October) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | India introduces a ban on smoking in public.[86] | India | |

| 2008 | Mainstream smoke, second-hand smoke | Statistics | More than 161,000 deaths attributed to lung cancer are counted in the year in the United States. Of these deaths, an estimated 10% to 15% are caused by factors other than first-hand smoking; equivalent to 16,000 to 24,000 deaths annually. Slightly more than half of the lung cancer deaths caused by factors other than first-hand smoking are found in nonsmokers. Clinical epidemiology of lung cancer links the primary factors closely tied to lung cancer in non-smokers as exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke, carcinogens including radon, and other indoor air pollutants.[87] | United States | |

| 2008 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | The World Health Organization declares that it does not consider the e-cigarette to be a legitimate smoking cessation aid.[24] | ||

| 2008 | Death | Mainstream smoke | Research | The World Health Organization names tobacco use as the world's single greatest preventable cause of death.[88] | |

| 2009 (July 1) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Ireland prohibits the advertising and display of tobacco products in all retail outlets.[89] | Ireland | |

| 2009 | Third-hand smoke | Research | The term "third-hand smoke" is coined to identify the residual tobacco smoke contamination that remains after the cigarette is extinguished and secondhand smoke has cleared from the air.[90][91] | ||

| 2009 | Myocardial infarction | Mainstream smoke | Research | A systematic review and meta-analysis find that bans on smoking in public places are associated with a significant reduction of incidence of heart attacks.[92] | |

| 2009 | Coronary heart disease | Mainstream smoke | Research | A report by the U.S. Institute of Medicine concludes that smoking bans reduce the risk of coronary heart disease and heart attacks, but the report's authors are unable to identify the magnitude of this reduction.[93] | United States |

| 2009 | Atherosclerosis | Second-hand smoke | Research | Epidemiological studies show that both active and passive cigarette smoking increase the risk of atherosclerosis.[94] | |

| 2009 | Pancreatic cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research shows that current smokers are diagnosed with pancreas cancer six to eight years sooner than never-smokers.[48] | |

| 2010 | Birth defect | Second-hand smoke | Research | Studies comparing females exposed to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and non-exposed females, demonstrate that females exposed while pregnant have higher risks of delivering a child with congenital abnormalities, longer lengths, smaller head circumferences, and low birth weight.[95] | |

| 2010 | Health risk | Third-hand smoke | Research | Research suggests that by-products of third-hand smoke may pose a health risk.[96] | |

| 2010 | Cancer | Third-hand smoke | Research | A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that nicotine residue which coats smokers as well as interior car or room surfaces can react with nitrous acid present in the air to create tobacco-specific nitrosamines, carcinogens found in tobacco products. It is also found that ensuring ventilation while a cigarette is smoked does not eliminate the deposition of third-hand smoke in an enclosed space, according to the study's authors.[97] | |

| 2010–2011 | Third-hand smoke | Research | Studies show that humans can be exposed to third-hand smoke through inhalation, skin contact, or ingestion. There are also many surfaces that can accumulate THS compounds. Common surfaces that humans come into contact with daily include couches, furniture, curtains, and car seats. THS is thought to potentially cause the greatest harm to infants and young children because younger children are more likely to put their hands in their mouths or be cuddled up to a smoker with toxins on their skin and clothes. Infants also crawl on the floor and eat from their hands without washing them first, ingesting the toxins into their still developing systems.[98][99] | ||

| 2011 (May 31) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Venezuela introduces a restriction upon smoking in enclosed public and commercial spaces.[100] | Venezuela | |

| 2011 (July) | Mainstream smoke | Public opinion | A Gallup poll reports that for the first time, a majority of Americans (59%) support a ban on smoking in all public places. | United States | |

| 2011 (October) | Third-hand smoke | Policy | Christus St. Frances Cabrini Hospital in Alexandria, Louisiana seeks to eliminate third-hand smoke and forbids its employees to work if their clothing smells of smoke. This prohibition is enacted after it is known that third-hand smoke poses a special danger for the developing brains of infants and small children.[101] | United States | |

| 2011 | Stroke | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research strongly associates passive smoking with an increased risk of stroke, and this increased risk is disproportionately high at low levels of exposure."[102] | |

| 2011 | Breast cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research finds that smokers exhibit an increased risk for breast cancer when compared to never-smokers.[103] | |

| 2011 | Stillbirth, congenital malformation | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke in women with stillbirth and congenital malformations in children.[104] | |

| 2011 | Second-hand smoke | Research | A commentary in Environmental Health Perspectives argues that research into "thirdhand smoke" renders it inappropriate to refer to passive smoking with the term "secondhand smoke", which the authors state constitutes a pars pro toto.[105] | ||

| 2012 | Cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 22% of cancer-deaths are attributable to tobacco use.[106] | |

| 2012 | Pancreatic cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | A Study finds no evidence that passive smoking is associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.[107] | |

| 2012 | Middle ear infection | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with increased risk of middle ear infections.[108][109] | |

| 2012 (March) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Brazil becomes the first country in the world to ban all flavored tobacco, including menthols. The majority of the estimated 600 additives used are also banned, permitting only eight. This regulation applies to domestic and internationally imported cigarettes.[110][111] | Brazil | |

| 2012 | Cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Jensen et al. show that nicotine is carcinogen for the gastrointestinal system.[112] | |

| 2013 | Lung cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research shows that passive smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer.[113] | |

| 2013 | Third-hand smoke | Concept development | A study with six focus groups in metro and rural Georgia (USA) asks participants whether they have heard of third-hand smoke. Most of the participants have not heard about it and does not know what third-hand smoke is.[114] | ||

| 2013 | Neural tube defects | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates maternal exposure to secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy with an increased risk of neural tube defects.[115] | |

| 2013 | Cognitive impairment, dementia | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research concludes that exposure to secondhand smoke may increase the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in adults 50 and over.[116] | |

| 2013 | DNA damage | Third-hand smoke | Research | Research suggests that thirdhand smoke causes DNA damage in human cells.[117] | |

| 2014 | Lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | A review finds that smoking cannabis doubles the risk of lung cancer, though cannabis is in many countries commonly mixed with tobacco.[118] | |

| 2013 | Prostate cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research suggests that current smokers have a reduced risk of prostate cancer compared with never-smokers.[48] | |

| 2014 | Learning difficulties, developmental delays, executive function problems | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with learning difficulties, developmental delays, and executive function problems.[119] | |

| 2014 | Sinusitis | Second-hand smoke | Research | The majority of studies find a significant association between secondhand smoke exposure and sinusitis.[120] | |

| 2014 | Miscarriage | Second-hand smoke | Research | A meta-analysis finds that maternal secondhand smoke exposure increases the risk of miscarriage by 11%.[121] | |

| 2014 | Allergic diseases | Second-hand smoke | Research | A systematic review and meta-analysis find that passive smoking is associated with a slightly increased risk of allergic diseases among children and adolescents. The evidence for an association is weaker for adults.[122] | |

| 2015 (January) | Sleep disordered breathing | Second-hand smoke | Research | Most studies find a significant association between passive smoking and sleep disordered breathing in children.[123] | |

| 2015 | Type 2 diabetes | Second-hand smoke | Research | A study associates second-hand smoke with type 2 diabetes.[124] | |

| 2015 | Asthma | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke exposure with an almost doubled risk of hospitalization for asthma exacerbation among children with asthma.[125] | |

| 2015 | Orofacial cleft | Second-hand smoke | Research | A study suggests that maternal passive smoking increases the risk of non-syndromic orofacial clefts by 50% among their children.[126] | |

| 2015 | Diabetes | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research indicates that it remains unclear whether the association between passive smoking and diabetes is causal.[127] | |

| 2015 | Meningococcal disease | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with invasive meningococcal disease.[128] | |

| 2015 | Mainstream smoke | Research | A study finds that about 17% of mortality due to cigarette smoking in the United States is due to diseases other than those usually believed to be related.[129] | United States | |

| 2015 | Psychosis | Mainstram smoke | Research | A meta-analysis finds that smokers are at greater risk of developing psychotic illness.[130] | |

| 2015 | Breast cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | A meta-analysis finds that the evidence that passive smoking moderately increases the risk of breast cancer has become "more substantial than a few years ago."[131] | |

| 2015 | Tuberculosis | Second-hand smoke | Research | Review suggests that passive smoking may increase the risk of tuberculosis infection and accelerate the progression of the disease, but the evidence remains weak.[132] | |

| 2015 | Cervical cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | An overview of systematic reviews finds that exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of cervical cancer.[128] | |

| 2015 | Depression | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research suggests that exposure to secondhand smoke is associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms.[133] | |

| 2015 | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | It is calculated than more than 1.1 billion individuals worldwide smoked tobacco in this year.[48] | Worldwide | |

| 2016 (January) | Mainstream smoke | Policy | Turkmenistan president Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov reportedly bans all tobacco sales in the country.[134] | Turkmenistan | |

| 2016 | Bladder cancer | Second-hand smoke | Research | A study finds that secondhand smoke exposure is associated with a significant increase in the risk of bladder cancer.[135] | |

| 2016 | Third-hand smoke | Research | A study is done to look at how long third-hand smoke (THS) stay in three different fabrics over a timespan of 72 hours and post washing. The three different fiber types include wool, cotton, and polyester. Levels of THS are measured using a self-designed surface acoustic wave gas sensor (SAW) which measures a frequency change when a compound is laid down on the surface of the sensor. The results of this study find that third-hand smoke tends to stay in wool the most right after smoking and polyester the least. Wool has the slowest desorption while polyester has the fastest. Also, the study concludes that even though doing laundry and washing these fibers with detergent is an effective way to get rid of some of the smoke, there is still a remaining THS residue left on all the fibers.[136] | ||

| 2016 | Atopic dermatitis | Second-hand smoke | Research | A systematic review and meta-analysis find that passive smoking is associated with a higher rate of atopic dermatitis.[137] | |

| 2016 | Cognitive deficits | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research reports that children exposed to secondhand smoke show reduced vocabulary and reasoning skills when compared with non-exposed children as well as more general cognitive and intellectual deficits.[138] | |

| 2016 | Periodontitis | Second-hand smoke | Research | A study associates second-hand smoke with a possible increased risk of periodontitis.[139] | |

| 2016 | Second-hand smoke | Research | A systematic review and meta-analysis find that passive smoking is associated with a higher rate of atopic dermatitis.[140] | ||

| 2016 | Third-hand smoke | Research | According to a study conducted by Northrup, 22% of infants and children are exposed to second-hand smoke, and third-hand smoke in their homes each year, comprising a major proportion of the 126 million nonsmokers exposed to harmful tobacco products annually.[141] | ||

| 2016 (October) | Cardiovascular disease | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with adverse effects on the cardiovascular system of children.[142] | |

| 2017 | Second-hand smoke | Research | As of date, passive smoking causes about 900,000 deaths a year, which is about 1/8 of all deaths caused by smoking.[143] | ||

| 2017 | Anesthesia complications | Second-hand smoke | Research | Research associates second-hand smoke with anesthesia complications and some negative surgical outcomes.[144] | |

| 2017 | Squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma | Mainstream smoke | Research | Research including almost 44,000 individuals finds an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a decreased risk of basal cell carcinoma in current smokers compared to never-smokers.[48] | |

| 2017 | Third-hand smoke | Research | A paper uses the concept of "cessation imperative", explaining that the only way to fully protect people from exposure to thirdhand smoke is for smokers to quit smoking because even smoking in places when others are not present can expose people to tobacco smoke contaminants.[145] | ||

| 2018 | Non-communicable disease | Mainstream smoke | Statistics | Research finds that 18% of noncommunicable disease (NCD) deaths are attributable to tobacco use in the European Region, meaning almost 1 in 5 premature NCD deaths could be avoided by eliminating tobacco use.[146] | WHO European Region |

| 2018 | Mainstream smoke | Research | A report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concludes, “while it is biologically plausible that nicotine can act as a tumor promoter, the existing body of evidence indicates this is unlikely to translate into increased risk of human cancer.”[147] | ||

| 2018 | Mainstream smoke | Policy | As of year, 169 states have signed the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which governs international tobacco control.[148][149] | Worldwide | |

| 2019 | Mainstream smoke | Research | The Surgeon General of the United States announces a link between serious disease and e-cigarettes, an alternative to smoking in which traditional tobacco companies heavily invest.[25] | United States | |

| 2019 | Tracheal cancer, bronchus cancer, lung cancer | Mainstream smoke | Research | The report from WHO/Europe “European tobacco use – trends report 2019” notes that almost 9 in 10 deaths (including premature deaths) from trachea, bronchus and lung cancer in the European Region are related to tobacco. In other words, 90% of lung cancers could be avoided by eliminating tobacco use.[146] | WHO European Region |

| 2025 | Mainstream smoke | Program | New Zealand hopes to achieve being tobacco-free by this year.[150] | New Zealand | |

| 2035 | Mainstream smoke | Program | The British Medical Assocation establishes the goal of a smokeless Britain by this year.[8] | United Kingdom | |

| 2040 | Mainstream smoke | Program | Finland hopes to achieve being tobacco-free by this year.[151] | Finland |

Numerical and visual data

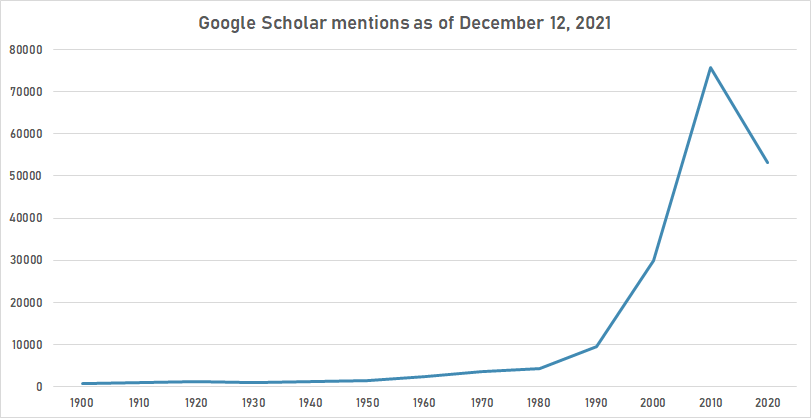

Google Scholar

The following table summarizes per-year mentions on Google Scholar as of December 12, 2021.

| Year | "tobacco" "disease" |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 776 |

| 1910 | 957 |

| 1920 | 1,130 |

| 1930 | 963 |

| 1940 | 1,250 |

| 1950 | 1,330 |

| 1960 | 2,440 |

| 1970 | 3,470 |

| 1980 | 4,210 |

| 1990 | 9,580 |

| 2000 | 29,900 |

| 2010 | 75,800 |

| 2020 | 53,200 |

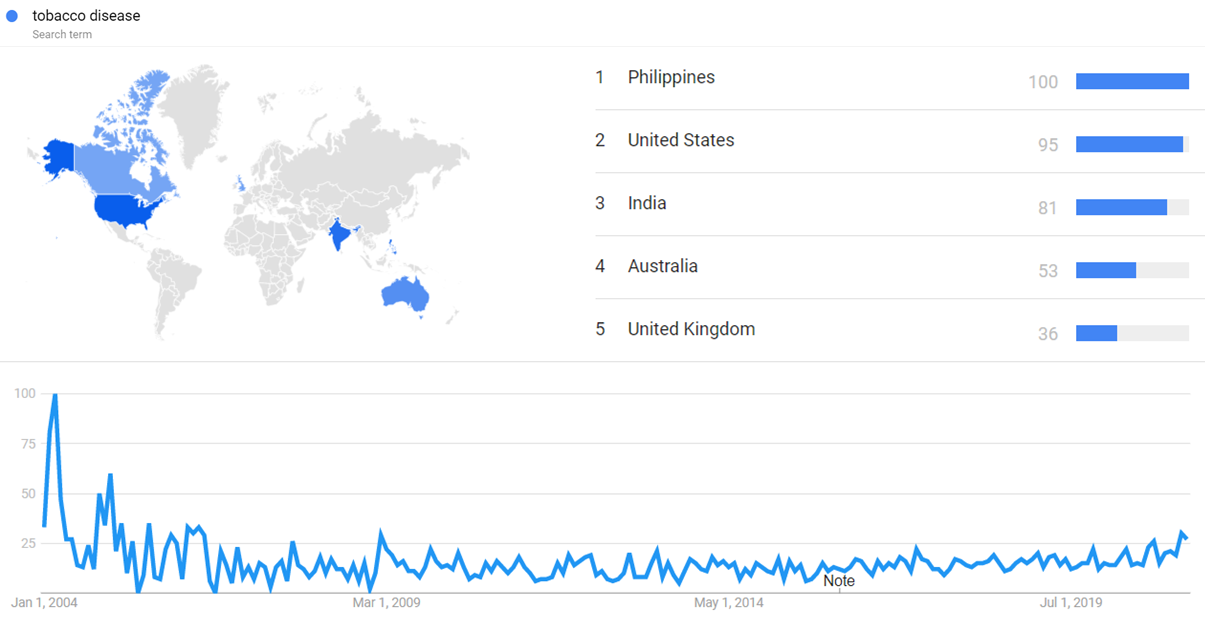

Google Trends

The chart below shows Google Trends data for Tobacco disease (Search term), from January 2004 to April 2021, when the screenshot was taken. Interest is also ranked by country and displayed on world map.[152]

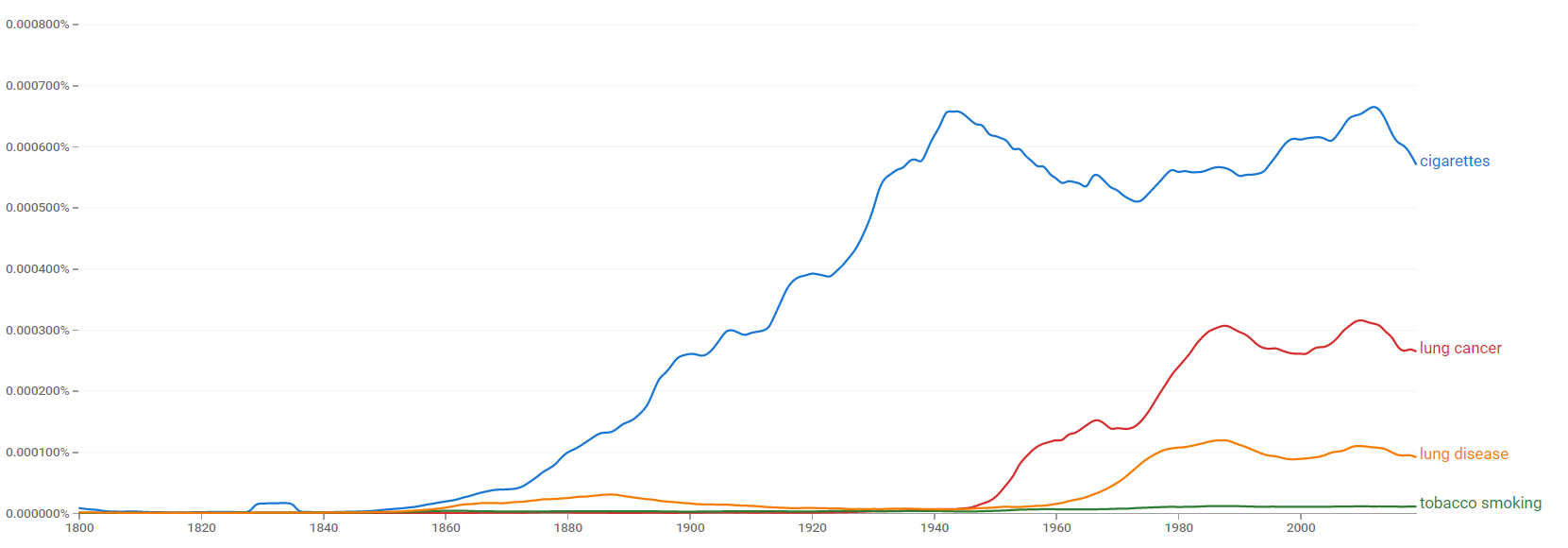

Google Ngram Viewer

The comparative chart below shows Google Ngram Viewer data for Cigarettes, lung cancer, tobacco smoking and lung disease, from 1800 to 2019.[153]

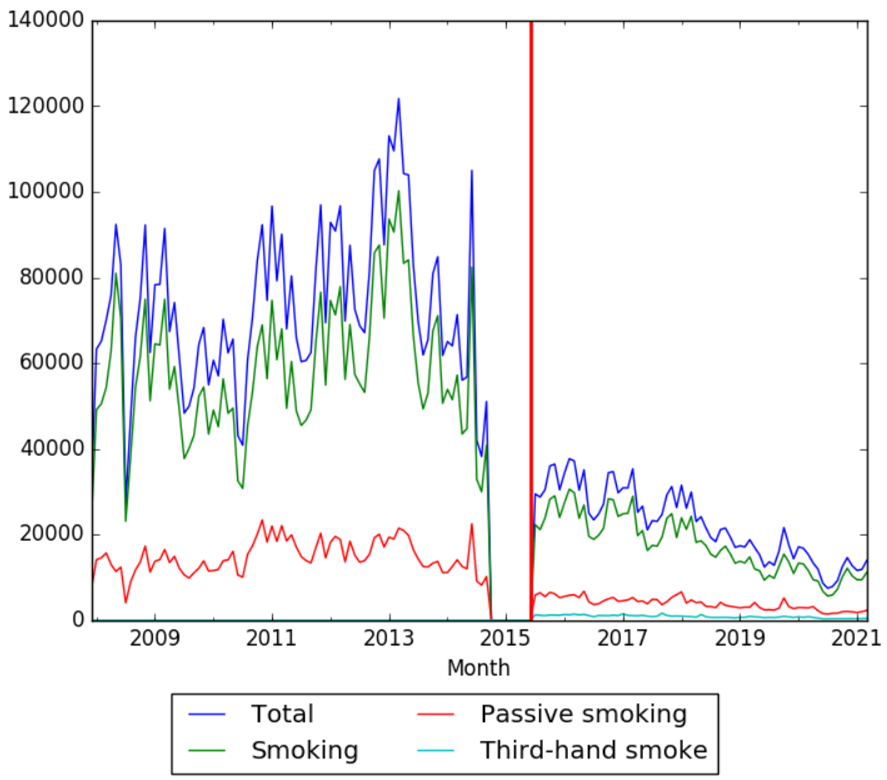

Wikipedia Views

The comparative chart below shows pageviews on desktop of the English Wikipedia articles Smoking, Passive smoking and Third-hand smoke, from December 2007 to March 2021. The data gap observed from October 2014 to June 2015 is the result of Wikipedia Views failure to retrieve data.[154]

Meta information on the timeline

How the timeline was built

The initial version of the timeline was written by User:Sebastian.

Funding information for this timeline is available.

Feedback and comments

Feedback for the timeline can be provided at the following places:

- FIXME

What the timeline is still missing

Timeline update strategy

See also

- Timeline of lung cancer

- Timeline of kidney cancer

- Timeline of liver cancer

- Timeline of bladder cancer

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 "Smoking and tobacco history - how things change" (PDF). tobacco.cleartheair.org.hk. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 "The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Proctor, Robert N. "The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll". doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050338.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 "History of Tobacco". academic.udayton.edu. Boston University MedicalCenter. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ↑ DANIELSSON, MARIA; GILLJAM, HANS; HEMSTRÖM, ÖRJAN. "Tobacco habits and tobacco-related diseases".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "WHO's goal to reduce smoking is achievable – the national Tobacco-Free Finland 2040 project requires stronger action" (PDF). julkari.fi. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ "Are current strategies to discourage smoking in Australia inequitable?". tobaccoinaustralia.org.au. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 Smith, Kyle. "Could smoking become extinct?". nypost.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑ Goodman, Jordan. Tobacco in History and Culture: An Encyclopedia (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2005).

- ↑ American Heritage Book of Indians, p.41

- ↑ Ley, Willy (December 1965). "The Healthfull Aromatick Herbe". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 88–98.

- ↑ Lader, Malcolm Harold; Henningfield, Jack E.; Martin Jarvis (1985). Nicotine, an old-fashioned addiction. London: Burke Publishing. pp. 96–8.

- ↑ "Which Mughal emperor prohibited the use of tobacco?". study.com. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 "The Ashtray of History". theatlantic.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑

Romaniello, Matthew P.; Starks, Tricia (2009). "Tabak: An Introduction". In Romaniello, Matthew; Starks, Tricia (eds.). Tobacco in Russian History and Culture: The Seventeenth Century to the Present. Routledge Studies in Cultural History. New York: Routledge (published 2011). p. 1–2. ISBN 9781135842895. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

The Russian prohibition lasted almost the entire seventeenth century, staying in place for seventy years, longer than anywhere else in the world. [...] Russia's reaction to tobacco was unique. While most countries banned tobacco upon its arrival, they legalized it shortly thereafter, generally less than ten years after the initial prohibition [...] which makes Russia's seventy-year-long ban surprising.

- ↑ Proctor, Robert N. The Nazi War on Cancer.

- ↑ "WELLINGTON ARCHITECTURE WEEK" (PDF). web.archive.org. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Richard Kluger, Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War (1996)

- ↑ Allan Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America (2007)

- ↑ "Pharmacology of Ganglionic Transmission". springer.com. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Alston, Lee J.; Dupré, Ruth; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada". Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445. doi:10.1016/S0014-4983(02)00005-0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ↑ Isaac Adler. "Primary Malignant Growth of the Lung and Bronchi". (1912) New York, Longmans, Green. pp. 3–12. Reprinted (1980) by A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Rodgman, Alan; Perfetti, Thomas A. The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "American Smoking Culture: From Cash Crop to Public Scourge". newsweek.com. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 "U.S. Surgeon General announces definitive link between smoking and cancer". history.com. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ Karagueuzian, Hrayr S; White, Celia; Sayre, James; Norman, Amos. "Cigarette Smoke Radioactivity and Lung Cancer Risk". doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr145. PMID 21956761.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 27.00 27.01 27.02 27.03 27.04 27.05 27.06 27.07 27.08 27.09 27.10 27.11 27.12 27.13 "The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General". Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ Finklea JF, Sandifer SH, Smith DD (November 1969). "Cigarette smoking and epidemic influenza". American Journal of Epidemiology. 90 (5): 390–9. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121084. PMID 5356947.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Chapman, S. (1 June 2003). "Other people's smoke: what's in a name?". Tobacco Control. 12 (2): 113–4. doi:10.1136/tc.12.2.113. PMC 1747703. PMID 12773710.

- ↑ "*** NORMATTIVA ***". www.normattiva.it. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ↑ Züllich G, Damm KH, Braun W, Lisboa BP (May 1975). "Studies on biliary excreted metabolites of [G-3H]digitoxin in rats". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 215 (1): 160–7. PMID 1156044.

- ↑ Kark JD, Lebiush M (May 1981). "Smoking and epidemic influenza-like illness in female military recruits: a brief survey". American Journal of Public Health. 71 (5): 530–2. doi:10.2105/AJPH.71.5.530. PMC 1619723. PMID 7212144.

- ↑ Kark JD, Lebiush M, Rannon L (October 1982). "Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for epidemic a(h1n1) influenza in young men". The New England Journal of Medicine. 307 (17): 1042–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM198210213071702. PMID 7121513.

- ↑ "Studies of Cancer in Humans".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Calkins BM (December 1989). "A meta-analysis of the role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 34 (12): 1841–54. doi:10.1007/BF01536701. PMID 2598752.

- ↑ Steenland K (January 1992). "Passive smoking and the risk of heart disease". JAMA. 267 (1): 94–9. doi:10.1001/jama.267.1.94. PMID 1727204.

- ↑ Nicholson KG, Kent J, Hammersley V (August 1999). "Influenza A among community-dwelling elderly persons in Leicestershire during winter 1993-4; cigarette smoking as a risk factor and the efficacy of influenza vaccination". Epidemiology and Infection. 123 (1): 103–8. doi:10.1017/S095026889900271X. PMC 2810733. PMID 10487646.

- ↑ Celermajer, David S.; Adams, Mark R.; Clarkson, Peter; Robinson, Jacqui; McCredie, Robyn; Donald, Ann; Deanfield, John E. (18 January 1996). "Passive Smoking and Impaired Endothelium-Dependent Arterial Dilatation in Healthy Young Adults". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (3): 150–155. doi:10.1056/NEJM199601183340303. PMID 8531969.

- ↑ Anderson, HR; Cook, DG (November 1997). "Passive smoking and sudden infant death syndrome: review of the epidemiological evidence". Thorax. 52 (11): 1003–9. doi:10.1136/thx.52.11.1003. PMC 1758452. PMID 9487351.

- ↑ Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE (1997). Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: the impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8058-2547-3.

- ↑ Sanner, Tore; Grimsrud, Tom K. "Nicotine: Carcinogenicity and Effects on Response to Cancer Treatment – A Review". doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00196. PMC 4553893. PMID 26380225. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Doherty EW, Doherty WJ (1998). "Smoke gets in your eyes: Cigarette smoking and divorce in a national sample of American adults". Families, Systems, & Health. 16 (4): 393–400. doi:10.1037/h0089864.

- ↑ Parrott AC (October 1999). "Does cigarette smoking cause stress?". The American Psychologist. 54 (10): 817–20. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.817. PMID 10540594.

- ↑ Howard, G; Thun, MJ (December 1999). "Why is environmental tobacco smoke more strongly associated with coronary heart disease than expected? A review of potential biases and experimental data". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 Suppl 6: 853–8. doi:10.2307/3434565. JSTOR 3434565. PMC 1566209. PMID 10592142.

- ↑ Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, Harrison LH, McGeer A, Kolczak MS, Breiman RF (March 2000). "Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (10): 681–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003093421002. PMID 10706897.

- ↑ "PROJECTIONS OF TOBACCO PRODUCTION, CONSUMPTION AND TRADE TO THE YEAR 2010". fao.org. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ↑ Otsuka R, Watanabe H, Hirata K, et al. (2001). "Acute effects of passive smoking on the coronary circulation in healthy young adults". JAMA. 286 (4): 436–41. doi:10.1001/jama.286.4.436. PMID 11466122.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 Jacob, Louis; Freyn, Moritz; Kalder, Matthias; Dinas, Konstantinos; Kostev, Karel. "Impact of tobacco smoking on the risk of developing 25 different cancers in the UK: a retrospective study of 422,010 patients followed for up to 30 years". doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24724. PMC 5915125. PMID 29707117. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Smoking". lungcancercanada.ca. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Jerry Markon; Renae Merle (13 April 2004). "Disparity in Protecting Food Service Staff from Secondhand Smoke Shows Need for Comprehensive Smoke-Free Policies, Say Groups" (Press release).

- ↑ Goedert JJ, Vitale F, Lauria C, Serraino D, Tamburini M, Montella M, Messina A, Brown EE, Rezza G, Gafà L, Romano N (November 2002). "Risk factors for classical Kaposi's sarcoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 94 (22): 1712–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.22.1712. PMID 12441327.

- ↑ "[ Explained ] The Cigarettes And Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition Of Advertisement And Regulation Of Trade And Commerce, Production, Supply And Distribution) Act, 2003". Nyaaya.in.

- ↑ Ministry of Health (15 September 2005). "Smokefree Law in New Zealand". moh.govt.nz. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ↑ Janson C (2004). "The effect of passive smoking on respiratory health in children and adults". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 8 (5): 510–6. PMID 15137524.

- ↑ Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ (October 2004). "Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors". American Journal of Epidemiology. 160 (8): 784–96. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh275. PMID 15466501.

- ↑ Mullally, Bernie J.; Greiner, Birgit A.; Allwright, Shane; Paul, Gillian; Perry, Ivan J. "The effect of the Irish smoke-free workplace legislation on smoking among bar workers". doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp008. PMC 2720734. PMID 19307250.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Braverman, Marc T.; Aarø, Leif Edvard; Hetland, Jørn. "Changes in smoking among restaurant and bar employees following Norway's comprehensive smoking ban". Health Promotion International. doi:10.1093/heapro/dam041.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 IARC 2004 "There is sufficient evidence that involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) causes lung cancer in humans"

- ↑ Burton, Adrian (2011). "Does the Smoke Ever Really Clear? Thirdhand Smoke Exposure Raises New Concerns". Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (2): A70–4. doi:10.1289/ehp.119-a70. PMC 3040625. PMID 21285011.

- ↑ Parameswaran, Gayatri. "Bhutan smokers huff and puff over tobacco ban". aljazeera.com. Aljazeera. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ↑ Jarvis MJ (January 2004). "Why people smoke". BMJ. 328 (7434): 277–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7434.277. PMC 324461. PMID 14751901.

- ↑ "Study Finds That New Jersey Bars and Restaurants Have Nine Times More Air Pollution than Those in Smoke-Free New York". web.archive.org. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑ Barnoya J, Glantz SA (2005). "Cardiovascular effects of secondhand smoke: nearly as large as smoking". Circulation. 111 (20): 2684–98. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492215. PMID 15911719.

- ↑ Peate I (2005). "The effects of smoking on the reproductive health of men". British Journal of Nursing. 14 (7): 362–6. doi:10.12968/bjon.2005.14.7.17939. PMID 15924009.

- ↑ Diethelm PA, Rielle JC, McKee M (2005). "The whole truth and nothing but the truth? The research that Philip Morris did not want you to see". Lancet. 366 (9479): 86–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66474-4. PMID 15993237.

- ↑ Schick S, Glantz S (2005). "Philip Morris toxicological experiments with fresh sidestream smoke: more toxic than mainstream smoke". Tobacco Control. 14 (6): 396–404. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.011288. PMC 1748121. PMID 16319363.

- ↑ "Proposed Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air Contaminant". California Environmental Protection Agency. 2005-06-24. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Cendon, S.P.; Battlehner, C.; Lorenzi; Filho, G.; Dohlnikoff, M.; Pereira, P.M.; Conceição, G.M.S.; Beppu, O.S.; Saldiva, P.H.N. (22 May 2005). "Pulmonary emphysema induced by passive smoking: an experimental study in rats". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research = Revista Brasileira de Pesquisas Medicas e Biologicas. 30 (10). SciELO Brasil: 1241–7. doi:10.1590/s0100-879x1997001000017. PMID 9496445. 507184.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ↑ "In quotes: Scotland's smoking ban". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ↑ Surgeon General 2006, p. 194

- ↑ Surgeon General 2006, pp. 311–9

- ↑ Vork KL, Broadwin RL, Blaisdell RJ (2007). "Developing Asthma in Childhood from Exposure to Secondhand Tobacco Smoke: Insights from a Meta-Regression". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (10): 1394–400. doi:10.1289/ehp.10155. PMC 2022647. PMID 17938726.

- ↑ "Secondhand Smoke and Children Fact Sheet", American Lung Association August 2006.

- ↑ "England to go smokefree on 1 July 2007: truly a time for celebration". ash.org.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ "WHO BENEFITS THE MOST FROM F1 SPONSORSHIP: THE TEAM OR THE SPONSOR?". drivetribe.com. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ "Motor racing, tobacco company sponsorship, barcodes and alibi marketing". doi:10.1136/tc.2011.043448.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Tobacco advertising in Formula One". thecarexpert.co.uk. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ More Smokers Feeling Harassed by Smoking Bans

- ↑ Ward C, Lewis S, Coleman T (May 2007). "Prevalence of maternal smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and impact on birth weight: retrospective study using Millennium Cohort". BMC Public Health. 7: 81. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-81. PMC 1884144. PMID 17506887.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Kroon LA (September 2007). "Drug interactions with smoking". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (18): 1917–21. doi:10.2146/ajhp060414. PMID 17823102.

- ↑ The Gallup Organization (March 2009). "Survey on Tobacco – Analytical Report" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ↑ "Scientific Consensus Statement on Environmental Agents Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders" (PDF). The Collaborative on Health and the Environment's Learning and Developmental Disabilities Initiative. July 1, 2008.

- ↑ Zhou, B; Yang, L; Sun, Q; Cong, R; Gu, H; Tang, N; Zhu, H; Wang, B. "Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis". doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.044. PMID 18501231.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Jones, DT; Osterman, MT; Bewtra, M; Lewis, JD (September 2008). "Passive smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (9): 2382–93. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01999.x (inactive 2020-05-07). PMC 2714986. PMID 18844625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2020 (link) - ↑ Avşar A, Darka O, Topaloğlu B, Bek Y (October 2008). "Association of passive smoking with caries and related salivary biomarkers in young children". Arch. Oral Biol. 53 (10): 969–74. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.05.007. PMID 18672230.

- ↑ Pandey G (2 October 2008). "Indian ban on smoking in public". BBC. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ↑ Samet JM, Avila-Tang E, Boffetta P, et al. (September 2009). "Lung cancer in never smokers: Clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors". Clin. Cancer Res. 15 (18): 5626–45. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0376. PMC 3170525. PMID 19755391.

- ↑ "WHO REPORT on the global TOBACCO epidemic, 2008" (PDF). who.int. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ↑ "Tobacco Control". hse.ie. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Winickoff JP, Friebely J, Tanski SE, et al. (January 2009). "Beliefs about the health effects of "thirdhand" smoke and home smoking bans". Pediatrics. 123 (1): e74–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2184. PMC 3784302. PMID 19117850.

- ↑ Rabin, Roni Caryn (2009-01-02). "A New Cigarette Hazard: 'Third-Hand Smoke'". New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ↑ Meyers DG, Neuberger JS, He J (September 2009). "Cardiovascular effect of bans on smoking in public places: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 54 (14): 1249–55. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.022. PMID 19778665.

- ↑ Blue, Laura (30 October 2012). "Smoke-Free Laws Are Saving Lives". Time. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Zou N, Hong J, Dai QY (February 2009). "Passive cigarette smoking induces inflammatory injury in human arterial walls". Chin. Med. J. 122 (4): 444–8. PMID 19302752.